4

Essential Interventions

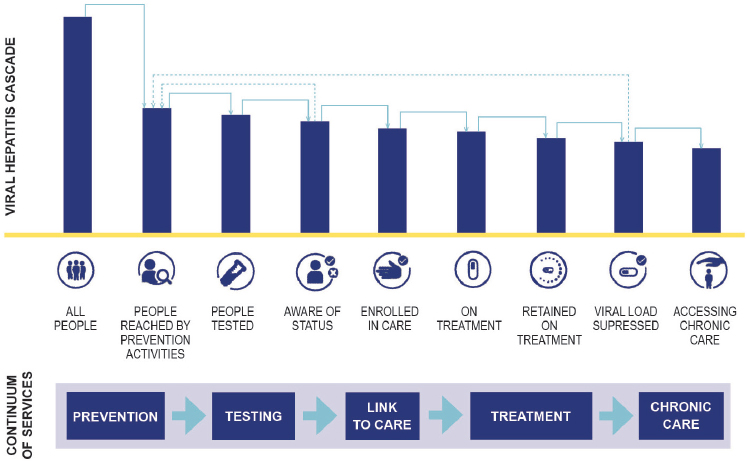

Viral hepatitis elimination is an international effort, but the scope of the problem varies by country. This committee’s previous report discussed the epidemiology of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the United States (NASEM, 2016). It discussed opportunities for ending transmission of both viruses, as well as steps to prevent the progression of HBV and HCV infection to cirrhosis and liver cancer (NASEM, 2016). With this epidemiological perspective in mind, this chapter discusses some crucial actions that would help reduce the national burden of both infections. In identifying interventions with the greatest potential effect, the committee considered the care cascade across the continuum of services shown in Figure 4-1. As much as possible, this chapter distinguishes between specific interventions against viral hepatitis and the manner in which such interventions are delivered, a topic covered in the next chapter.

PREVENTION AND TESTING

Prevention is the first step to making HBV and HCV infections rare. Hepatitis B is preventable with immunization, so prevention is a matter of ensuring widespread vaccination and taking steps to prevent transmission from mother to child. There is no prophylactic vaccine for HCV, so services to prevent hepatitis C involve controlling the practices known to spread the virus and curing chronic infections. Since both viruses are transmitted primarily through blood contact, risk reduction measures most associated with hepatitis C and HIV are also useful to prevent HBV infection.

SOURCE: WHO, 2016a.

Prevention of HBV Infection

Hepatitis B is preventable. The vaccines licensed in the 1980s confer durable immunity to 95 percent of people who receive three doses (CDC, 2016d,f; Mast et al., 2005; Walayat et al., 2015). When the three-dose vaccine series is started at birth, children are protected against acquisition during the vulnerable preschool years; the birth dose also helps prevent vertical transmission of HBV. Among a subset of HBsAg+ pregnant women with high viremia, risk of prophylaxis failure is higher (Chen et al., 2012). About 900 neonates a year contract HBV at birth in the United States (Ko et al., 2014). This number too could be reduced.

Perfect vaccination of children would end HBV transmission in two generations, but the elimination goals set out in Chapter 2 require faster action than that (Forcione et al., 2002). In the United States, better attention to adult vaccination and changes to the management of HBsAg+ pregnant women may be all that stands in the way of ending the transmission of HBV.

Vaccination of Adults

The prevalence of HBV in children decreased markedly after the introduction of hepatitis B vaccine (Wasley et al., 2010). As of 2013, about

90 percent of children under 3 were fully immunized against HBV (Elam-Evans et al., 2014). Vaccine-induced immunity is far less common in adults, however (Wasley et al., 2010). Only about a quarter of adults older than 19 participating in the 2014 National Health Interview Survey reported having had three doses of hepatitis B vaccine (24.5 percent, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]: 23.8 to 25.3), roughly the same percentage as the previous year (Williams et al., 2016). Likelihood of full vaccination is only slightly better among people who travel internationally (30.5 percent, 95 percent CI: 29.2 to 31.8) (Williams et al., 2016).

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended universal adult hepatitis B vaccination in places where a high proportion of people are likely at risk for HBV infection, such as clinics targeting people who inject drugs or men who have sex with men; it also recommended a standing order to identify adults for whom hepatitis B immunization is recommended in primary care and specialty clinics; it recommended that all diabetes patients be immunized against HBV in 2011 (CDC, 2011b; Mast et al., 2006). Yet adult hepatitis B vaccination coverage remains low, even in high-risk groups (CDC, 2011b; Mast et al., 2005). Only 29.8 percent of patients with chronic liver disease (95 percent CI: 23.9 to 36.5 percent), and 23.5 percent of diabetics aged 19 to 59 (95 percent CI: 20.7 to 26.7 percent) have been immunized (Williams et al., 2016). Studies have found low immunization coverage among people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men at HIV clinics, and clients at sexually transmitted disease clinics (Bowman et al., 2014; Collier et al., 2015; Henkle et al., 2015; Hoover et al., 2012). Hepatitis B infection is also an occupational hazard for health care workers, who can be exposed to infected blood or tissue through needle stick and other sharp injuries, yet many health care workers remain unvaccinated. Only about two-thirds of providers in direct patient care have been immunized—well below the Healthy People 2020 target of 90 percent (Byrd et al., 2013; HHS, n.d.; Talas, 2009; Williams et al., 2016).

Unvaccinated adults remain vulnerable to HBV infection through unprotected sex, unsafe injections and transfusions, and contact with infected blood. Thirty to 50 percent of adults who contract HBV will develop symptoms of acute hepatitis, a condition with a mortality rate of 0.5 to 1 percent (CDC, 2016f; Immunization Action Coalition, n.d.; Mast et al., 2006). About 5 percent will develop chronic hepatitis B (Mast et al., 2006; WHO, 2016b).

From 2009 to 2013, three Appalachian states reported a 114 percent increase in the incidence of acute hepatitis B infection associated with increased injection drug use among white men in their thirties (Harris et al., 2016a). In 2014, adults accounted for about 95 percent of the estimated 19,200 cases of acute hepatitis B in the United States (CDC, 2016i). Rates

of acute infection were highest in those aged 30 to 39 years in 2014 (2.23 cases per 100,000 people) and have increased slightly in ages 40 to 59 years from 2010 to 2014 (CDC, 2016i). Non-Hispanic blacks had the highest rate of acute hepatitis B infection in 2014 (CDC, 2016i).

There are many reasons for low adult hepatitis B vaccine coverage. There is not good public awareness about hepatitis B; even health workers can be uninformed of its risk (Ferrante et al., 2008; Patil et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2016). Clinics often fail to stock the hepatitis B vaccine, partly because there is no funding to deliver it to uninsured and underinsured people, and partly because they fear losing clients over the lengthy three-dose schedule (Daley et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2016). Some states require a prescription even for vaccination at a pharmacy (ASTHO, 2014).

Adult immunization does not have to be so complicated. Every year since 2009 about 40 percent of adults in the United States have received seasonal flu vaccine; coverage among those over 65 years is even better, around two-thirds (CDC, 2016b,c). If states supported hepatitis B vaccination to the same level as seasonal influenza vaccine, great improvements could be made in hepatitis B immunization.

Recommendation 4-1: States should expand access to adult hepatitis B vaccination, removing barriers to free immunization in pharmacies and other easily accessible settings.

The relative success of seasonal influenza immunization is partly a matter of making vaccination convenient, especially for hard-to-reach patients, including homeless people and substance users (Vlahov et al., 2007). Offering vaccination in pharmacies is one way to reach a broader cross-section of the population. Many pharmacies are open evenings and weekends, making them convenient to people whose jobs do not allow paid leave. Data from Walgreens pharmacies in 49 states showed that about 30 percent of vaccinations were given during off-clinic hours (meaning weekends, evenings, and holidays) (Goad et al., 2013). The same data showed 40 percent of 18- to 49-year-olds seeking immunizations at Walgreens came during off-hours; 37 percent were uninsured (Goad et al., 2013).

All states now authorize pharmacists to vaccinate, but many restrict the types of vaccines and circumstances under which pharmacists can administer them (American Pharmacists Association, 2015; Bach and Goad, 2015; Immunization Action Coalition, 2016). Pharmacists can administer hepatitis B vaccine in all states except New Hampshire and New York, although Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, North Carolina, and Puerto Rico require a prescription for the vaccine, and 34 states have age restrictions on hepatitis B vaccination in pharmacies (American Pharmacists Association, 2016).

State laws on the reimbursement of vaccination delivered in pharmacies

also vary widely (Bach and Goad, 2015). Payment for vaccination can come from private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, or out-of-pocket (ASTHO, 2014). Provisions to simplify reimbursement, such as the Medicare mass immunizer program, reduce the administrative barriers to vaccination, but hepatitis B vaccine is not included in the mass immunizer program (ASTHO, 2014; CMS, 2016a,b).

The CDC can fund state and local health departments to buy vaccines through section 317 of the Public Health Service Act, but the vast majority of these funds go to childhood immunizations (Orenstein et al., 2007). Section 317 funding is meant “to fill critical public health needs,” and as such would be appropriately spent on viral hepatitis elimination (CDC, 2016h).

The specific actions needed to make hepatitis B vaccine more widely available will vary by state. In Hawaii, which has a large population of Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians, pharmacies can provide the hepatitis B vaccine series; the state’s MinuteClinics can also screen for HCV (CVS Health, 2016). Prisons and jails are also an ideal venue for hepatitis B vaccination, a topic discussed in the next chapter.

Reluctance to vaccinate against HBV in nontraditional settings may stem from some confusion over the importance of adherence to the standard dose schedule. Protective immunity to HBV is found in 30 to 55 percent of healthy adults after one dose of the vaccine (Mast et al., 2004, 2006). A two-dose vaccine schedule has been shown to confer immunity in 82.9 percent of healthy adults (95 percent CI 76.1 to 89.7 percent) (Wong et al., 2014). Patients may fear, erroneously, that receiving extra doses of the vaccine is harmful, a point that should be clarified for all vaccine providers. Similarly, when the interval between doses is lengthened there is no need to restart the series (CDC, 2016e). Some research has shown that delaying the last dose for years may even improve antibody response (Jackson et al., 2007; Junewicz et al., 2014).

Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission

HBV is far more efficiently transmitted from mother to child than HIV or HCV (Benova et al., 2014; Connor et al., 1994; Dienstag, 2015). Without intervention, about 90 percent of infants born to HBeAg+ women will contract the virus at birth (CDC, 2016d; Ko et al., 2014). Infants infected at birth are prone to chronic hepatitis B infection, which carries a 25 percent risk of premature death from liver cancer or cirrhosis later in life (Beasley and Hwang, 1991; CDC, 2016e; Mast et al., 2005). Timely hepatitis B vaccination and hepatitis B immune globulin after birth are highly effective in preventing most infants born to HBsAg+ mothers from developing chronic hepatitis B infection (Mast et al., 2005). In 1988, ACIP recommended universal screening of all pregnant women for HBsAg and that babies born

to HBsAg+ mothers receive hepatitis B immune globulin and the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours of birth (CDC, 1988). In 1990, the CDC established a national perinatal hepatitis B prevention program (CDC, 2011a). The program aims to identify HBsAg+ pregnant women and enroll them in case management to ensure their infants receive timely immunoprophylaxis and serologic testing after completion of the vaccine series (CDC, 2011a). By 2000, 50 percent of the more than 20,000 births to HBsAg+ mothers were enrolled in the program, and new cases of chronic hepatitis B in infants declined from almost 6,000 cases in 1990 to about 1,000 in 2000 (Smith et al., 2012b; Ward, 2015).

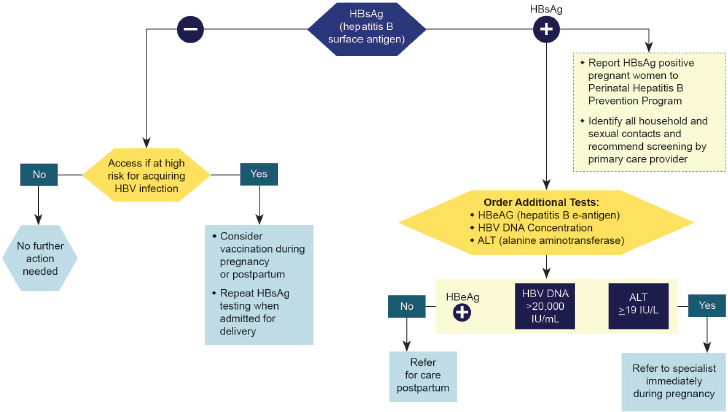

Despite the initial good progress, further reduction in perinatal HBV transmission has lagged. Ideally all HBsAg+ pregnant women should be referred to a specialist for perinatal and long-term care, as ACIP recommended in 2005 (Mast et al., 2005). But of the estimated 25,000 to 26,000 HBsAg+ women who give birth in the United States each year, only about half are identified for case management, a proportion unchanged since 2000 (Smith et al., 2012b). In 2015 the CDC and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) developed an algorithm showing the tests necessary for HBsAg+ pregnant women and the results which should trigger referral to a specialist (see Figure 4-2). Still, every year an estimated 800 to 1,000 infants (or about 3.8 percent of babies born to HBsAg+ mothers) become chronically infected from vertical transmission (Ko et al., 2014).

By some estimates as many as 96.7 percent of HBsAg+ pregnant women are tested in their first trimester (Ko et al., 2014). It is crucial that their newborns receive a dose of hepatitis B vaccine within 12 to 24 hours of birth to prevent transmission of the virus, but hepatitis B birth dose coverage1 in the United States was only 63.9 percent in 2015 (CDC, 2016a). ACIP aimed to correct this in 2016 by recommending that all infants receive the initial dose of the hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth (Chitnis, 2016; Jenco, 2016).

Infants born to highly viremic HBsAg+ mothers have increased risk of immunoprophylaxis failure. A prospective observational study in Australia found that 9 percent of infants born to mothers with HBV DNA greater than 20 million IU/mL (7.3 log10 IU/mL or 100 million copies/mL) developed chronic hepatitis B infection (despite post-exposure prophylaxis with hepatitis B vaccine and immune globulin), but none of the babies born to women with lower HBV DNA did (Wiseman et al., 2009). A recent analysis of cases of hepatitis B immunoprophylaxis failure in California between 2005 and 2011 found 92 percent of cases had HBV DNA greater than 20 million IU/mL (Burgis et al., 2014).

Prophylactic antiviral therapy in the third trimester of pregnancy will

___________________

1 Within 24 hours of birth.

SOURCE: CDC, 2015.

further reduce perinatal HBV transmission among highly viremic women. A recent randomized trial of prophylactic tenofovir treatment in such patients (median HBV DNA 8.19 log10 IU/mL) prevented transmission of HBV without serious consequences to the newborn or complications to the delivery (Pan et al., 2016). At the same time, women may experience hepatitis flare after stopping treatment postpartum and require long-term antiviral therapy, which carries a risk of unclear potential for drug resistance in subsequent pregnancies (ter Borg et al., 2008).

Current practice guidelines in Australia recommend that pregnant women with HBV DNA greater than 10 million IU/mL (7 log10 IU/mL) be referred to a specialist for consideration for prophylactic tenofovir therapy (ASHM, 2014). The 2015, AASLD2 guidelines set a lower threshold, recommending pregnant women with an HBV DNA level greater than 200,000 IU/mL be considered for prophylactic antiviral therapy, while acknowledging the need for research to establish a more precise treatment threshold (Terrault et al., 2016).

Hepatitis B flare is common during pregnancy and after delivery and can lead to liver failure (Elefsiniotis et al., 2015; Giles et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2009; ter Borg et al., 2008). It is therefore important to monitor

___________________

2 Officially, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

liver enzymes in HBsAg+ pregnant women. A retrospective study of 29 pregnant women with chronic hepatitis B found three women developed severe hepatitis flare or liver failure and required antiviral therapy, and one woman required a liver transplant (Nguyen et al., 2009).

Recommendation 4-2: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists should recommend that all HBsAg+ pregnant women have early prenatal HBV DNA and liver enzyme tests to evaluate whether antiviral therapy is indicated for prophylaxis to eliminate mother-to-child transmission or for treatment of chronic active hepatitis.

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HBV is clearly a priority for the CDC, one referenced in the national viral hepatitis action plan (HHS, 2015). Affirmation of the importance of early viremia testing from CDC leadership would help enforce this point. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), AASLD, and ACOG also command the attention of important stakeholders on this question: the doctors who manage hepatitis B in pregnant women. Leadership from these societies would help draw attention to this essential service and end the vertical transmission of HBV.

Prevention of HBV and HCV Infections

Until there is a vaccine for HCV, prevention will be mainly a matter of limiting exposure to the virus. One component of prevention (discussed later in this chapter) is curing all infected persons of their chronic infection. Another is preventing the blood contact that spreads HCV, as well as HBV and HIV infections. In some countries this means better screening of donor blood, ending use of reusable syringes, or reducing demand for unnecessary medical injections (WHO, 2016a). In the United States about 75 percent of the roughly 30,500 new HCV infections a year are caused by injection drug use (Klevens et al., 2014; University of Washington, n.d.-a). A key step to ending transmission of HCV in the United States is reducing the risk of infection among people who inject drugs.

Injection Drug Use and HCV Infection

The United States has a drug injection problem of epidemic proportions (Dart et al., 2015; Kolodny et al., 2015). The nonmedical use of prescription opioids has risen sharply since 2000 (Keyes et al., 2014). National survey data suggest that 435,000 Americans use heroin, and another 4.3

million report illicit use of prescription pain medicines (SAMHSA, 2015a). These proportions could shift over time; heroin is often easier to buy and cheaper than prescription opioids, causing people addicted to painkillers to switch (Cicero et al., 2014; Dart et al., 2015). The CDC estimates that death from opioid overdose has increased 200 percent since 2000, a situation described as “an unprecedented epidemic” (HHS, 2013; Rudd et al., 2016).

The opioid problem is not simply a matter of more people using addictive drugs; a different cross-section of society is involved than was a generation ago. In the 1960s, heroin use was mostly confined to cities; users were predominantly young, male, and disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities (Cicero et al., 2014). In contrast, people who have become addicted to opioids in the last decade are male and female, overwhelmingly white, and living in rural areas, suburbs, and small towns (Akyar et al., 2016; Cicero et al., 2014). Nowadays about half of people who inject drugs live outside of cities, often in relative isolation, in areas not well equipped to access medical care or addiction treatment services (Havens et al., 2013; Oster et al., 2015). In rural counties deaths from drug overdose have increased three times faster than in urban ones (Keyes et al., 2014).

HCV infection is a serious health consequence of injection drug use. Studies from the early 2000s suggest an HCV antibody prevalence among people who inject drugs of 70 to 77 percent (Nelson et al., 2011). About a third of people who inject drugs acquire HCV infection in their first year of injecting (Hagan et al., 2008). Controlling HCV among drug injectors is challenging. The syringe exchange programs3 that have reduced HIV incidence are less effective against hepatitis C (Des Jarlais et al., 2015; Holtzman et al., 2009). HCV transmission by needle stick is 10 times more efficient than for HIV (Bruggmann and Grebely, 2015; Siddharta et al., 2016). HCV is also a relatively hardy virus, able to survive on fomites for hours or even days (Krawczynski et al., 2003; Valdiserri et al., 2014). For these reasons, needle or syringe sharing accounts for only about 63 percent of the risk of HCV infection among people who inject drugs, because the virus can survive on other equipment including cotton filters and rinse water (Hagan et al., 2010).

Opioid Agonist Therapy

The most effective way to prevent hepatitis C among people who inject drugs is to combine strategies that improve the safety of injection with those that treat the underlying addiction (Cox and Thomas, 2013; Hagan et al.,

___________________

3 Also called syringe services.

2010). Opioid agonist therapy4 refers to the use of prescription medicines to bind opiate receptors in the brain, thereby relieving the symptoms of withdrawal (IOM, 1995). Such therapy is part of the tertiary prevention of substance use disorders, meaning that it prevents the worst complications of the disorder, including overdose and transmission of blood-borne infections (Kolodny et al., 2015). Before 2000, opioid agonists could only be prescribed in drug treatment clinics, but now the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) issues waivers to doctors who, after registering with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), can prescribe buprenorphine-based formulations in routine practice (FDA, n.d.; SAMHSA, 2017).5 Still, the opioid epidemic created more demand for services, and by 2012 demand exceeded capacity by between 1.3 and 1.4 million (Jones et al., 2015). In response to this shortage, SAMHSA increased the maximum patient load per waived provider to 275, and expanded the role of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in managing buprenorphine therapy (HHS, 2016c; SAMHSA, 2015b).

Nevertheless, most of the waivers have been issued to doctors on the coasts (HHS, 2016c; Rosenblatt et al., 2015; SAMHSA, 2015b). A 2012 analysis found that 30 million Americans live in places where not a single provider can prescribe opioid agonists (Rosenblatt et al., 2015). There is a need for wider access to treatment for opioid dependence, especially in rural areas (Rosenblatt et al., 2015; Stein et al., 2015). Recent studies in rural Colorado, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania are exploring strategies, such as tele-psychiatry, to bring opioid use treatment to rural areas (AHRQ, 2016). Regarding medications, long-acting buprenorphine and naltrexone formulations may be more suitable in such areas (Kjome and Moeller, 2011; Laffont et al., 2016). When naltrexone is administered via a sustained-release implant, for example, it can be active in blood, controlling drug cravings, for up to 6 months (Hulse et al., 2009; Kjome and Moeller, 2011).

Syringe Exchange

Syringe exchange programs in the United States do not have sufficient coverage even in cities; availability is worse in rural areas (Des Jarlais et al.,

___________________

4 Including full agonist therapy with methadone and partial agonist therapy with buprenorphine, sometimes complemented with the antagonist treatment naloxone (SAMHSA, 2015c, 2016).

5 The waiver program only authorized the prescription of buprenorphine, alone or in combination with naloxone. Other opioid agonists are still restricted. For example, the DEA categorizes methadone as Schedule II drug, meaning that it has a high potential for abuse and dependence (DEA, n.d.). Therefore, methadone can only be prescribed in conjunction with drug treatment programs certified by SAMHSA (SAMHSA, 2015c).

2015). Despite serving, in theory, half the people who inject drugs, rural and suburban areas have only 30 percent of the nation’s syringe services and distribute almost 29 million fewer syringes (only about 8 percent of the total) (Des Jarlais et al., 2015; Oster et al., 2015). Of every dollar spent on syringe services in the United States, about 17 cents goes to rural or suburban areas (Des Jarlais et al., 2015). With fewer staff and smaller budgets, rural programs have to reach people injecting drugs in remote parts of the country, such as Appalachia, and vast ones, such as the Central Valley. When syringe services are far away, people are less likely to use them (Allen et al., 2015; Cooper et al., 2011). Transportation challenges can pale in comparison to the problem of protecting clients’ privacy, something often taken for granted in the relative anonymity of big cities (Benyo, 2012).

Part of the value of both opioid agonist therapy and syringe exchange programs is that they provide clients with an entry point to the health system (MacNeil and Pauly, 2011). Staff at exchanges, especially case managers, can also help interested clients enroll in drug counseling or cessation programs. A randomized, controlled trial in Baltimore syringe exchange programs found that clients working with case managers were 87 percent more likely to enter drug treatment within a week of their referral than clients without such support (Strathdee et al., 2006). Staff can also counsel clients on the use of naloxone to treat overdose and offer testing for viral hepatitis and HIV. Three-quarters of syringe exchange programs responding to a 2013 survey reported offering HCV testing, though the proportion was lower in rural areas (Des Jarlais et al., 2015). Ensuring linkage to care is more challenging; fewer than half of survey respondents (a third in rural areas) reported tracking the referral process for clients who tested positive (Des Jarlais et al., 2015).

Although legally prohibited in the United States, supervised injection facilities, clinics where people can inject under clinical supervision, may be another means of harm reduction (Drug Policy Alliance, 2016). Supervised injection has been shown to reduce death from overdose; in Vancouver, the introduction of such a facility was associated with a 35 percent reduction in the rate of fatal overdose, compared to only a 9 percent reduction in other parts of the city (Marshall et al., 2011). A 2006 review (predating curative treatment for hepatitis C) concluded that “it is plausible that these rooms can contribute to a reduced incidence of HCV” through reducing the sharing of injecting equipment (Wright and Tompkins, 2006). The possibility of curing HCV infection in a crucial population may warrant revisiting the strategy. A supervised injection facility in Vancouver reported an 87.6 percent prevalence of HCV antibody among its clients (Wood et al., 2005). A systematic review of research (mainly from Canada and Australia) found supervised sites to be effective at reaching people with unstable housing and a recent history of incarceration (Potier et al., 2014).

Syringe exchange and opioid agonist treatment are cornerstones of viral hepatitis elimination. But these services are least available in the places that most need them, rural areas with an injection opioid problem (see Box 4-1). It is no coincidence that the same four states (Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia) that saw a 364 percent increase in acute HCV infection between 2006 and 2012 have documented unmet needs for syringe services (Des Jarlais et al., 2015; Zibbell et al., 2015). Expanding harm reduction services (both exchanges and opioid agonist therapy) to rural and suburban areas is complicated, as these parts of the country are characterized by fewer resources for health and principled opposition to anything seen to facilitate illicit drug use (Havens et al., 2013; Valdiserri et al., 2014). Such obstacles can be overcome, but only with commitment from states and federal agencies.

Recommendation 4-3: States and federal agencies should expand access to syringe exchange and opioid agonist therapy in accessible venues.

The epidemic of nonmedical opioid use has captured the attention of policy makers and providers, with new emphasis on diagnosing substance use disorder and using opioid agonist therapy to treat it when possible (Tetrault and Butner, 2015). Syringe services and treatment for substance use disorder, essential parts of the response to the opioid epidemic, can also prevent transmission of HCV (HHS, 2013; Volkow et al., 2014). Action against the opioid epidemic complements work on viral hepatitis elimination, with attention to the two goals benefiting both.

UNAIDS6 reckons that every person who injects drugs needs about 200 syringes a year, something few exchange programs can provide (UNAIDS, 2014). In some states, drug paraphernalia laws and rules regulating the prescription and sale of syringes can present an obstacle to full coverage (Burris et al., 2002) (see Box 4-1). In states without such restrictions, and with public funding available to syringe exchange programs, more equipment is distributed and the programs can offer complementary services, including HCV testing (Bramson et al., 2015). Tracking the number of syringes distributed and the number of people who inject drugs in a program’s coverage area could, in theory, afford a measure of progress against the UNAIDS target, though in practice it is difficult to estimate the latter with any precision (Abdul-Quader et al., 2013). Evidence regarding unmet need for syringe services may help persuade legislators to remove restrictions on them, including the restrictions on the number of syringes exchanged per visit or per client.

The North American Syringe Exchange Network periodically surveys

___________________

6 Officially, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

exchanges regarding services provided, budget, and annual number of syringes exchanged (CDC, 2010; North American Syringe Exchange Network, n.d.). Such surveys will be valuable in charting progress on this recommendation and determining if the reach of the exchanges is expanding. Other valuable indicators will be the number of providers authorized to provide buprenorphine, and the number of people in opioid treatment programs.

Expansion of syringe exchange to rural and suburban areas may require modifications to models developed in cities. Pharmacies are an accessible venue for people who inject drugs across a range of settings (Hammett et al., 2014). Pharmacies in some jurisdictions can sell or distribute syringes, dispose of used ones, dispense naloxone for overdose, and test for HIV (Hammett et al., 2014). When it is legal to buy syringes at pharmacies, more people who inject drugs do so (Siddiqui et al., 2015). Pharmacies are often reasonably equipped to provide confidential space for patient counseling. Research in Rhode Island suggests that pharmacists and other pharmacy staff are willing to counsel clients who inject drugs on prevention and referrals for treatment when appropriate (Zaller et al., 2010). Where pharmacists are not willing to participate, education may help persuade them (Chiarello, 2016; Crawford et al., 2013). It is also essential to have clear laws and an unambiguous store or franchise policy supporting syringe exchange, so that no pharmacist fears retribution from management for dispensing syringes (Chiarello, 2016; Crawford et al., 2013). Some reluctant pharmacists may be reassured by data showing that syringe sales at pharmacies are not associated with any increase in crime in the surrounding area (Stopka et al., 2014).

Mobile syringe exchange has the potential to reach a wide cross-section of people who inject drugs. Mobile exchanges typically operate from a van or bus, allowing them to bring services to their clients and to cover a wide area, conveying advantages in rural areas (WHO, 2007). In cities, mobile programs are often meant to supplement fixed sites (Ivsins et al., 2010). When the only fixed-site syringe exchange in Victoria, British Columbia, closed, syringe distribution in the city fell by a third (Ivsins et al., 2010). Clients familiar with the fixed site complained that the switch to mobile clinics made it more difficult to safely dispose of syringes and to obtain clean ones (Ivsins et al., 2010). On the other hand, mobile programs often face less community opposition than fixed sites (Ivsins et al., 2010; WHO, 2007). Some observational studies suggest that mobile sites may be more acceptable to younger clients and to people engaging in higher risk behavior (Jones et al., 2010). Mobile programs may also be more desirable in places where clients may fear harassment or public shaming (WHO, 2007).

Widening the reach of syringe exchange is ideologically complicated (Rich and Adashi, 2015). Introducing such programs to new places requires

sensitivity to local norms. Although the evidence indicates that exchange programs do not recruit new users or increase drug use among clients, people whose communities are being devastated by drug use may understandably object to actions seen to enable it (Bramson et al., 2015; Vlahov and Junge, 1998). When such programs were starting in response to HIV, cultural opposition to them was particularly strong among police officers and African American and Hispanic community leaders (Anderson, 1991; Barreras and Torruella, 2013; Bramson et al., 2015; Singer et al., 1991). Such attitudes can change, especially if community members are convinced of the exchange programs’ effectiveness to reduce disease and keep used needles off the streets (Barreras and Torruella, 2013; Keyl et al., 1998). Police officers in some areas have come to favor exchange programs, citing reduced risk of needle stick injury on the job and benefit to the community

(Davis et al., 2014). Project sponsors would do well to encourage local consultation in new exchange programs.

Expansion of opioid agonist therapy will also be essential to preventing viral hepatitis infections. The Surgeon General’s 2016 report Facing Addiction in America concluded that while medications are effective in treating serious substance use disorders, too few providers are able to prescribe them (HHS, 2016a). The increase in the allowable patient limit on providers managing buprenorphine therapy could help improve the reach of this essential health service. The Surgeon General’s report also argued for better integration of opioid agonist therapy into mainstream medical practices (as opposed to separate substance abuse clinics) as a way to improve efficiency and lead to better health outcomes (HHS, 2016b). Consistent with this emerging consensus, the 2016 Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act aimed to make evidence-based treatments for opiate addiction more available around the country, including to incarcerated people (Community

Anti-Drug Coalitions of America, n.d.). A better discussion of reaching people who inject drugs and people in prisons with a range of viral hepatitis services follows in the next chapter.

Testing and Screening

Identifying people infected with HBV or HCV will be crucial to elimination, as the models presented in Chapter 2 indicate. The value of screening is already affirmed in the CDC and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines, which recommend screening people at high risk of infection for both HBV and HCV (see Table 4-1); Chapter 5 discusses strategies to improve compliance with these guidelines. At the same time, chronic viral hepatitis is often clinically silent until its later stages. Early detection is the first step to preventing the complications of untreated infection. Wider screening for hepatitis C may be warranted in the United States, as it accounts for a considerably larger share of the national burden of viral hepatitis.

HCV Screening

In 1998 the CDC recommended screening for HCV among people with the known risk factors for infection shown in Box 4-2 (CDC, 1998; University of Washington, n.d.-b). By 2014, however, it was evident that at least 20 percent of people with hepatitis C had no discernable risk factor for the infection, and that almost three-quarters were born between 1945 and 1965 (CDC, 2016i). In 2012 the CDC changed its recommendation to encourage one-time HCV testing for everyone born between 1945 and 1965 (CDC, 2012). The following year the USPSTF followed suit, revising its 2004 statement cautioning against widespread screening of asymptomatic adults, but that was a year before direct-acting antivirals came on the market (Moyer, 2013).

Screening for HCV has increased since 2013, with increasing attention given to the best strategies to implement the USPSTF recommendation (Sidlow and Msaouel, 2015; Turner et al., 2015). Recent estimates suggest that about 15 to 20 percent of the 1945 to 1965 birth cohort is screened in primary care (Bourgi et al., 2016; Linas et al., 2014). Insufficient staff time and competing demands on providers’ attention, a problem discussed in the next chapter, has been cited as a reason for the uneven implementation of the recommendation, as has providers’ unwillingness to inquire about risk factors (Jewett et al., 2015; Southern et al., 2014). It is not clear that provider education can improve this. One 15-week intervention to improve adherence to national guidelines saw adherence to screening decrease from

TABLE 4-1 USPSTF Recommendations and Important Risk Groups for HBV and HCV Screening

| HBV | HCV | |

|---|---|---|

| USPSTF Recommendation | The USPSTF recommends screening for HBV infection in persons at high risk for infection. | The USPSTF recommends screening for HCV infection in persons at high risk for infection. The USPSTF also recommends offering one-time screening for HCV infection to adults born between 1945 and 1965. |

| Important Risk Groups for Screening |

Important risk groups (in non-pregnant adolescents and adults) for HBV infection that should be screened include

|

Important risk groups for HCV infection that should be screened include

|

NOTE: HBV = hepatitis B virus; HCV = hepatitis C virus; USPSTF = U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

SOURCES: CDC, 2016g; LeFevre, 2014; Moyer, 2013.

almost 60 percent at the start to about 13 percent in the last week (Southern et al., 2014).

Some settings have actively pursued wider HCV screening, including urban emergency departments, safety net providers for the uninsured. Screening in an Oakland emergency room found an HCV antibody prevalence of almost 14 percent among those in the 1945 to 1965 birth cohort, 38 percent among people who inject drugs, and about 3 percent among

people with neither risk factor (White et al., 2016). A similar program at an urban tertiary care hospital in Alabama found that one in every nine emergency department patients born between 1945 and 1965 had HCV antibody, nearly four times higher than the previously reported prevalence for that group (Galbraith et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2012a). Moreover, cases found in urban emergency rooms could be missed under current risk-based and birth cohort screening guidelines. Twenty-five percent of cases found in Baltimore and 28 percent in Cincinnati emergency departments were among people with no reported risk factor for the virus; an ambulatory care center in the Bronx, also a safety net provider, found 3 percent prevalence of HCV antibody in people with no obvious risk factors (Hsieh et al., 2016; Lyons

et al., 2016; Southern et al., 2011). For these reasons, some researchers have suggested universal testing at clinics and hospitals that serve high-risk populations (Southern et al., 2011).

Mathematical models indicate that one-time universal adult screening for HCV would identify 446,700 patients who would be missed with birth cohort screening (Kabiri et al., 2014). As the elimination effort continues, expanding testing, especially in settings likely to see high-risk patients, may be the key to continued progress (Edlin, 2011).

Recommendation 4-4: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should work with states to identify settings appropriate for enhanced viral hepatitis testing based on expected prevalence.

The decision to make a policy of widespread testing for any disease cannot be taken lightly. The procedure comes at an expense to the health system and puts a burden on providers. It also has the potential to cause distress in patients, especially when the disease screened for carries a social stigma, as viral hepatitis does. On the other hand, society stands to benefit from any measure that sheds light on the subclinical burden of HBV and HCV infections. The ability of direct-acting antivirals to cure infection can also change the risk to benefit calculation over time. The CDC, in cooperation with its state and local partners, has the ability to identify populations that would benefit from heightened screening, especially if state and local health offices make the surveillance improvements described in Chapter 3.

There are core antigen tests for HCV with sensitivity of 90 percent and specificity of 98 percent (Freiman et al., 2016). There are, at present, no Food and Drug Administration-approved point-of-care hepatitis B tests in the United States, partly because the relatively low prevalence of hepatitis B translates into less incentive to manufacturers to seek market authorization. The next chapter of this report discusses measures that could improve adherence to established screening guidelines. Taken together, adherence to existing guidelines and enhanced screening in certain settings might contribute to a greater demand for screening assays, and prompt manufacturers to seek U.S. licensure for these products.

CARE AND TREATMENT

The direct-acting antivirals that cure chronic HCV infection are what make elimination of hepatitis C as a public health problem a feasible goal in the United States; their importance cannot be understated (Palese, 2016). At this time there are no comparable curative therapies for chronic hepatitis B, a problem discussed in Chapter 7. Identification of chronic HBV infections and their appropriate treatment will be crucial to ending transmission of the

virus and to preventing death from chronic infection (NASEM, 2016). Entecavir and tenofovir are highly effective at suppressing the virus and cost-effective even over decades (Eckman et al., 2011; Hutton et al., 2007). The management of chronic HBV infection requires wide access to integrated, comprehensive care, a topic discussed in Chapter 5.

Curing Chronic HCV Infection

Hepatitis C treatments are costly, a topic discussed in detail in Chapter 6. The combination of cost and demand for these medicines has strained the budgets of many payers (Brennan and Shrank, 2014; Saag, 2014; Steinbrook and Redberg, 2014; Trooskin et al., 2015). In response, insurers have established criteria for prescription approval, such as evidence of advanced liver fibrosis or consultation with a specialist (Barua et al., 2015; Simon et al., 2015). Many insurers require a period of abstinence from drugs and alcohol; some confirm this with drug testing (Grebely et al., 2015). Restrictions in state Medicaid programs have drawn particular scrutiny; criteria for approval vary widely among states (Barua et al., 2015; Canary et al., 2015). As of 2015, 74 percent of Medicaid programs required evidence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis; 69 percent required prescription by or consultation with a specialist, and half required a period of abstinence from drugs and alcohol (Barua et al., 2015). Another six states required patients to undergo liver biopsy prior to treatment (Barua et al., 2015).

Because of the varying restrictions imposed by insurers, the process to obtain approval for direct-acting antiviral prescriptions has become laborious. These drugs are often listed as specialty products, a classification that requires a higher out-of-pocket payment from the patient, so when coverage is approved, the charge to the patient is often unaffordable (Rodriguez and Reynolds, 2016). Among callers to a hepatitis C hotline, about 40 percent were commercial insurance clients asking for help paying for treatment, and a quarter were Medicare beneficiaries in the same position (Rodriguez and Reynolds, 2016).

Another strategy to control costs is to require these prescriptions undergo a pre-approval process (sometimes called prior authorization) to determine if the patient meets the insurer’s criteria for treatment, a process that can require considerable effort on the part of providers (Barua et al., 2015; Edlin, 2011; Trooskin et al., 2015). The insurer reviews the prior authorization request and either approves the filling of the prescription or issues a denial. If the prescription is denied, the prescriber can appeal the decision, but the appeals process requires further documentation and review. Prescriptions that ultimately are not filled because of a lack of approval by the insurer are considered absolutely denied. Absolute denial of direct-acting antivirals is not uncommon. The Yale Liver Center reported

that a quarter of its patients were denied ledipasvir-sofosbuvir upon first request (Do et al., 2015).

There is evidence of disparities in access to direct-acting antivirals. A cohort study of hepatitis C patients in the mid-Atlantic region analyzed the rate of absolute denial of treatment among Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurers (Lo Re et al., 2016). 16.2 percent (95 percent CI: 14.8 to 17.8 percent) of the 2,321 patients were denied the drugs, most commonly on the grounds that the documentation provided was not sufficient information to assess medical need or lack of medical necessity (Lo Re et al., 2016). Absolute denial was significantly more common among Medicaid patients, whose treatment was refused at a rate of 46.3 percent (adjusted risk relative to commercial insurance patients: 4.14; 95 percent CI: 3.38 to 5.08), compared to Medicare (5.0 percent refusal; adjusted risk relative to commercial insurance patients: 0.61; 95 percent CI: 0.43 to 0.86) or commercial insurance patients (10.2 percent refusal) (Lo Re et al., 2016). Among cirrhotics, a quarter of Medicaid beneficiaries were denied treatment, compared to almost none of those with other types of insurance (Lo Re et al., 2016).

Another cohort study evaluated reasons why hepatitis C patients prescribed a sofosbuvir-based regimen never start it (Younossi et al., 2016). Out of 3,841 patients, 315 (8 percent) did not start the prescribed therapy; financial reasons and the insurance companies’ process accounted for 81 percent of such cases. As in the Lo Re study, non-start (among patients who did not start therapy for financial or insurance reasons) was highest among Medicaid beneficiaries (35 percent, 95 percent CI: 30 to 40 percent) compared to patients covered with either Medicare (2 percent, 95 percent CI: 1 to 3 percent) or commercial insurance (6 percent, 95 percent CI: 5 to 7 percent) (Younossi et al., 2016).

The disparity in access to direct-acting antivirals has caught public attention, obliging the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to formally remind state Medicaid directors that restricting access as a way to control costs is disallowed (CMS, 2015). In 2016 a class action lawsuit against the Washington state Medicaid agency ended in the ruling that restricting therapy to patients with advanced fibrosis was a violation of the Social Security Act (Aleccia, 2016). The threat of similar legal action caused the Delaware Medicaid program to rescind its access restrictions in June 2016 (Rini, 2016). State programs in Florida, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania have recently followed the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in removing all disease severity restrictions on hepatitis C treatment (Hughes, 2016; Kennedy, 2016; Lynch and McCarthy, 2016; Massachusetts EOHHS, 2016; Sapatkin, 2016). Since 2014, 16 state Medicaid programs have reduced their restrictions on treatment, although some states are not clear about the details of their policies (Hughes, 2016; Kennedy, 2016;

Lynch and McCarthy, 2016; Massachusetts EOHHS, 2016; NVHR and CHLPI, 2016; Sapatkin, 2016).

The committee commends Medicaid programs that have removed fibrosis restrictions on treatment. Patients denied access to hepatitis C treatment can have continued progression of hepatic fibrosis and remain at risk for cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Delaying treatment until hepatic fibrosis is more advanced has been shown to increase the risk of cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death, and the tests used to stage fibrosis cannot do so with great accuracy (Degos et al., 2010; Tsochatzis et al., 2011). Research in the VA system suggests that deferring anti-HCV therapy until the development of advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis reduces the value of the treatment and increases the risk of liver-related complications and death (McCombs et al., 2015). Denial of direct-acting antiviral treatment allows for ongoing liver inflammation, which can increase the risk of extra-hepatic complications. There are also consequences to society. As Appendix B makes clear, universal treatment of all hepatitis C patients would reduce infections 90 percent by 2030 (relative to 2015 levels). By the same token, failure to treat chronic HCV infection enlarges the reservoir for transmission, while denying treatment can cause anxiety and may provoke distrust of the health system.

Recommendation 4-5: Public and private health plans should remove restrictions that are not medically indicated and offer direct-acting antivirals to all chronic hepatitis C patients.

Curing chronic hepatitis C has immense clinical benefit (Pearlman and Traub, 2011). Cured patients, even cirrhotics, may experience a reversal of hepatic fibrosis over time (Everson et al., 2008; Mallet et al., 2008; Maylin et al., 2008; Shiratori et al., 2000). Reduction in fibrosis and return to normal liver function is associated with a decreased risk of hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and all-cause mortality (van der Meer et al., 2012). Cure of chronic hepatitis C can also help eliminate HCV transmission (Harris et al., 2016b; Martin et al., 2016). It is plausible that curing chronic hepatitis C will also improve the many complications of infection, including bone, kidney, cardiovascular, and neuropsychiatric problems (Adinolfi et al., 2015; Butt et al., 2011; Freiberg et al., 2011; Lo Re et al., 2012, 2015; Tsui et al., 2007). It also improves overall quality of life for the hepatitis C patient (Smith-Palmer et al., 2015; Younossi and Henry, 2015).

Treating HCV infection is also cost-effective. In a review of both the clinical and financial value of direct-acting antiviral therapy, the California Technology Assessment Forum found that although treating all patients is costly, the benefits are sufficient to make it cost-effective (Tice et al., 2015).

Delaying treatment increases costs; it costs less to cure people who have never been through a course of treatment before and to cure people before they progress to cirrhosis, further evidence for the effectiveness of early action (Chhatwal et al., 2015; Rein et al., 2015; Younossi et al., 2015). Additionally, patients who are cured of chronic HCV infection have significantly lower medical expenses than those who are not (Smith-Palmer et al., 2015; Younossi and Henry, 2014).

Treating everyone with chronic HCV infection, regardless of disease stage, would avert considerable suffering and anxiety. It is also a financially sensible course of action in the long run. IDSA and AASLD issued a joint statement in collaboration with the International Antiviral Society-USA supporting treatment for everyone with chronic HCV infection (AASLD and IDSA, 2015). The ability of these drugs to eradicate HCV infection in nearly all infected people has made the prospect of eliminating viral hepatitis in the United States plausible. Public and private health plans should not interfere with this goal. They should remove restrictions on direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C patients. The committee recognizes that the cost of the drugs presents an obstacle to implementing this recommendation. A strategy to better manage these costs is discussed in Chapter 6.

REFERENCES

AASLD and IDSA (American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America). 2015. Hepatitis C guidance underscores the importance of treating HCV infection: Panel recommends direct-acting drugs for nearly all patients with chronic hepatitis C. http://hcvguidelines.org/sites/default/files/when-and-in-whom-to-treat-press-release-october-2015.pdf (accessed November 14, 2016).

Abdul-Quader, A. S., J. Feelemyer, S. Modi, E. S. Stein, A. Briceno, S. Semaan, T. Horvath, G. E. Kennedy, and D. C. Des Jarlais. 2013. Effectiveness of structural-level needle/syringe programs to reduce HCV and HIV infection among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior 17(9):2878-2892.

Adinolfi, L. E., R. Nevola, G. Lus, L. Restivo, B. Guerrera, C. Romano, R. Zampino, L. Rinaldi, A. Sellitto, M. Giordano, and A. Marrone. 2015. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection and neurological and psychiatric disorders: An overview. World Journal of Gastroenterology 21(8):2269-2280.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2016. Increasing access to medication-assisted treatment of opioid abuse in rural primary care practices. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/primary-care/increasing-access-to-opioid-abuse-treatment.html (accessed February 14, 2017).

Akyar, E., K. H. Seneca, S. Akyar, N. Schofield, M. P. Schwartz, and R. G. Nahass. 2016. Linkage to care for suburban heroin users with hepatitis C virus infection, New Jersey, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases 22(5):907-909.

Aleccia, J. 2016. Judge orders Washington Medicaid to provide lifesaving hepatitis C drugs for all. Seattle Times, May 28. http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/judge-orders-apple-health-to-cover-hepatitis-c-drugs-for-all (November 9, 2016).

Allen, S., M. Ruiz, and A. O’Rourke. 2015. How far will they go? Assessing the travel distance of current and former drug users to access harm reduction services. Harm Reduction Journal 12:3.

American Pharmacists Association. 2015. Pharmacist-administered immunizations: What does your state allow? https://www.pharmacist.com/pharmacist-administered-immunizations-what-does-your-state-allow (accessed December 6, 2016).

American Pharmacists Association. 2016. Pharmacist administered vaccines: Types of vaccines authorized to administer. http://pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/Slides%20on%20Pharmacist%20IZ%20Authority_July_2016%20v2mcr.pdf?dfptag=imz (accessed December 8, 2016).

Anderson, W. 1991. The New York needle trial: The politics of public health in the age of AIDS. American Journal of Public Health 81(11):1506-1517.

ASHM (Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine). 2014. 10.0 Managing hepatitis B virus infection in pregnancy and children. http://hepatitisb.org.au/10-0-managing-hepatitis-b-virus-infection-in-pregnancy-and-children (accessed November 21, 2016).

ASTHO (Association of State and Territorial Health Officials). 2014. Pharmacy legal toolkit: Guidance and templates for state and territorial health agencies when establishing effective partnerships with pharmacies during routine and pandemic influenza seasons. Arlington, VA: ASTHO.

Bach, A. T., and J. A. Goad. 2015. The role of community pharmacy-based vaccination in the USA: Current practice and future directions. Dove Press 4:67-77. https://www.dovepress.com/the-role-of-community-pharmacy-based-vaccination-in-the-usa-current-pr-peer-reviewed-article-IPRP (accessed December 6, 2016).

Barreras, R. E., and R. A. Torruella. 2013. New York City’s struggle over syringe exchange: A case study of the intersection of science, activism, and political change. Journal of Social Issues 69(4):694-712.

Barua, S., R. Greenwald, J. Grebely, G. J. Dore, T. Swan, and L. E. Taylor. 2015. Restrictions for Medicaid reimbursement of sofosbuvir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 163(3):215-223.

Beasley, R., and L. Hwang. 1991. Overview of the epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. In Viral hepatitis and liver disease. Proceedings of the 1990 international symposium on viral hepatitis and liver disease, edited by F. B. Hollinger, S. Lemon, and H. S. Margolis. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

Benova, L., Y. A. Mohamoud, C. Calvert, and L. J. Abu-Raddad. 2014. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 59(6):765-773.

Benyo, A. 2012. Promoting secondary exchange: Opportunities to advance public health, edited by J. Curry and D. Raymond. New York: Harm Reduction Coalition.

Bourgi, K., I. Brar, and K. Baker-Genaw. 2016. Health disparities in hepatitis C screening and linkage to care at an integrated health system in southeast Michigan. PLoS One 11(8):e0161241.

Bowman, S., L. E. Grau, M. Singer, G. Scott, and R. Heimer. 2014. Factors associated with hepatitis B vaccine series completion in a randomized trial for injection drug users reached through syringe exchange programs in three U.S. cities. BMC Public Health 14:820.

Bramson, H., D. C. Des Jarlais, K. Arasteh, A. Nugent, V. Guardino, J. Feelemyer, and D. Hodel. 2015. State laws, syringe exchange, and HIV among persons who inject drugs in the United States: History and effectiveness. Journal of Public Health Policy 36(2):212-230.

Brennan, T., and W. Shrank. 2014. New expensive treatments for hepatitis C infection. JAMA 312(6):593-594.

Bruggmann, P., and J. Grebely. 2015. Prevention, treatment and care of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy 26(Suppl 1):S22-S26.

Burgis, J., D. Kong, C. Salibay, J. Zipprich, K. Harriman, and S. So. 2014. Tu1129 Risk factors associated with immunoprophylaxis failure in infants born to mothers with chronic hepatitis B infection in California. Gastroenterology 146(5):S-762.

Burris, S., S. A. Strathdee, and J. S. Vernick. 2002. Syringe access law in the United States: A state of the art assessment of law and policy. Baltimore, MD: Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Johns Hopkins and Georgetown Universities.

Butt, A. A., X. Wang, and L. F. Fried. 2011. HCV infection and the incidence of CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 57(3):396-402.

Byrd, K. K., P. J. Lu, and T. V. Murphy. 2013. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among healthcare personnel in the United States. Public Health Reports 128(6):498-509.

Callahan, R. 2016. Indiana counties must fund needle exchanges sans state help. http://www.wcpo.com/news/state/state-indiana/indiana-counties-must-fund-needle-exchanges-sans-state-help (accessed December 1, 2016).

Canary, L. A., R. M. Klevens, and S. D. Holmberg. 2015. Limited access to new hepatitis C virus treatment under state Medicaid programs. Annals of Internal Medicine 163(3):226-228.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1988. Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee prevention of perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus: Prenatal screening of all pregnant women for hepatitis B surface antigen. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 37(22):341-346, 351. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00000036.htm (accessed December 6, 2016).

CDC. 1998. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis c virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 47(RR19) :1-39.

CDC. 2010. Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 59(45):1488-1491. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5945a4.htm#tab2 (accessed February 23, 2017).

CDC. 2011a. Assessing completeness of perinatal hepatitis B virus infection reporting through comparison of immunization program and surveillance data—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(13):410-413.

CDC. 2011b. Use of hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes mellitus: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(50):1709-1711.

CDC. 2012. CDC now recommends all baby boomers receive one-time hepatitis C test. http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2012/hcv-testing-recs-pressrelease.html (accessed November 15, 2016).

CDC. 2015. Screening and referral algorithm for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection among pregnant women. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/pdfs/prenatalhbsagtesting.pdf (accessed February 6, 2017).

CDC. 2016a. ChildVaxView. 2015 hepatitis B (HepB) vaccination coverage among children 19-35 months by state, HHS region, and the United States, National Immunization Survey (NIS), 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/childvaxview/data-reports/hepb/reports/2015.html (accessed January 11, 2017).

CDC. 2016b. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2014-15 influenza season. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1415estimates.htm (accessed December 6, 2016).

CDC. 2016c. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2015-16 influenza season. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1516estimates.htm (accessed December 6, 2016).

CDC. 2016d. Hepatitis B. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/hepb.html (accessed 2016, November 3).

CDC. 2016e. Hepatitis B FAQs for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq.htm#overview (accessed November 7, 2016).

CDC. 2016f. Hepatitis B FAQs for the public. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/bfaq.htm#bFAQ15 (accessed January 24, 2017).

CDC. 2016g. Hepatitis C FAQs for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section1 (accessed October 25, 2016).

CDC. 2016h. Questions answered on vaccines purchased with 317 funds. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/guides-pubs/qa-317-funds.html (accessed February 23, 2017).

CDC. 2016i. Surveillance for viral hepatitis—United States, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2014surveillance/commentary.htm (accessed December 6, 2016).

Chen, H. L., L. H. Lin, F. C. Hu, J. T. Lee, W. T. Lin, Y. J. Yang, F. C. Huang, S. F. Wu, S. C. Chen, W. H. Wen, C. H. Chu, Y. H. Ni, H. Y. Hsu, P. L. Tsai, C. L. Chiang, M. K. Shyu, P. I. Lee, F. Y. Chang, and M. H. Chang. 2012. Effects of maternal screening and universal immunization to prevent mother-to-infant transmission of HBV. Gastroenterology 142(4):773-781.

Chhatwal, J., F. Kanwal, M. S. Roberts, and M. A. Dunn. 2015. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of hepatitis C virus treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 162(6):397-406.

Chiarello, E. 2016. Nonprescription syringe sales: Resistant pharmacists’ attitudes and practices. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 166:45-50.

Chitnis, D. 2016. ACIP approves change to hepatitis B vaccination guidelines. Pediatric News, MDedge. http://www.mdedge.com/pediatricnews/article/116025/vaccines/acip-approves-change-hepatitis-b-vaccination-guidelines (accessed November 21, 2016).

Cicero, T. J., M. S. Ellis, H. L. Surratt, and S. P. Kurtz. 2014. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: A retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry 71(7):821-826.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2015. Medicaid drug rebate notice: Assuring Medicaid beneficiaries access to hepatitis C (HCV) drugs. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/prescription-drugs/downloads/rx-releases/state-releases/state-rel-172.pdf (accessed November 14, 2016).

CMS. 2016a. Mass immunizers and roster billing: Simplified billing for influenza virus and pneumococcal vaccinations. CMS, HHS, and the Medicare Learning Network.

CMS. 2016b. Provider resources. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prevention/Immunizations/Providerresources.html (accessed December 6, 2016).

Collier, M. G., J. Drobeniuc, J. Cuevas-Mota, R. S. Garfein, S. Kamili, and E. H. Teshale. 2015. Hepatitis A and B among young persons who inject drugs—Vaccination, past, and present infection. Vaccine 33(24):2808-2812.

Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America. n.d. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA). http://www.cadca.org/comprehensive-addiction-and-recovery-act-cara (accessed February 23, 2017).

Connor, E. M., R. S. Sperling, R. Gelber, P. Kiselev, G. Scott, M. J. O’Sullivan, R. VanDyke, M. Bey, W. Shearer, R. L. Jacobson, and et al. 1994. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine 331(18):1173-1180.

Conrad, C., H. M. Bradley, D. Broz, S. Buddha, E. L. Chapman, R. R. Galang, D. Hillman, J. Hon, K. W. Hoover, M. R. Patel, A. Perez, P. J. Peters, P. Pontones, J. C. Roseberry, M. Sandoval, J. Shields, J. Walthall, D. Waterhouse, P. J. Weidle, H. Wu, and J. M. Duwve. 2015. Community outbreak of HIV infection linked to injection drug use of oxymorphone—Indiana, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64(16):443-444.

Cooper, H. L., D. C. Des Jarlais, Z. Ross, B. Tempalski, B. Bossak, and S. R. Friedman. 2011. Spatial access to syringe exchange programs and pharmacies selling over-the-counter syringes as predictors of drug injectors’ use of sterile syringes. American Journal of Public Health 101(6):1118-1125.

Cox, A. L., and D. L. Thomas. 2013. Hepatitis C virus vaccines among people who inject drugs. Clinical Infectious Diseases 57(Suppl 2):S46-S50.

Crawford, N. D., S. Amesty, A. V. Rivera, K. Harripersaud, A. Turner, and C. M. Fuller. 2013. Randomized, community-based pharmacy intervention to expand services beyond sale of sterile syringes to injection drug users in pharmacies in New York City. American Journal of Public Health 103(9):1579-1582.

CVS Health. 2016. CVS Health offering expanded hepatitis care options in Hawaii. https://cvshealth.com/newsroom/press-releases/cvs-health-offering-expanded-hepatitis-care-options-hawaii (accessed December 6, 2016).

Daley, M. F., K. A. Hennessey, C. M. Weinbaum, S. Stokley, L. P. Hurley, L. A. Crane, B. L. Beaty, J. C. Barrow, C. I. Babbel, L. M. Dickinson, and A. Kempe. 2009. Physician practices regarding adult hepatitis B vaccination: A national survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36(6):491-496.

Dart, R. C., H. L. Surratt, T. J. Cicero, M. W. Parrino, S. G. Severtson, B. Bucher-Bartelson, and J. L. Green. 2015. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 372(3):241-248.

Davis, C. S., J. Johnston, L. de Saxe Zerden, K. Clark, T. Castillo, and R. Childs. 2014. Attitudes of North Carolina law enforcement officers toward syringe decriminalization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 144:265-269.

DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration). n.d. Drug scheduling. https://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml (accessed February 23, 2017).

Degos, F., P. Perez, B. Roche, A. Mahmoudi, J. Asselineau, H. Voitot, and P. Bedossa. 2010. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and comparison to liver fibrosis biomarkers in chronic viral hepatitis: A multicenter prospective study (the FIBROSTIC study). Journal of Hepatology 53(6):1013-1021.

Des Jarlais, D. C., A. Nugent, A. Solberg, J. Feelemyer, J. Mermin, and D. Holtzman. 2015. Syringe service programs for persons who inject drugs in urban, suburban, and rural areas—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64(48):1337-1341.

Dienstag, J. L. 2015. Overview of the epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. PowerPoint presentation to the Committee on a National Strategy on the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C, Washington, DC, November 30, 2015. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/PublicHealth/HepatitisBandC/1-November2015/4-%20Jules%20Dienstag.pdf (accessed January 10, 2017).

Do, A., Y. Mittal, A. Liapakis, E. Cohen, H. Chau, C. Bertuccio, D. Sapir, J. Wright, C. Eggers, K. Drozd, M. Ciarleglio, Y. Deng, and J. K. Lim. 2015. Drug authorization for sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (Harvoni) for chronic HCV infection in a real-world cohort: A new barrier in the HCV care cascade. PLoS One 10(8):e0135645.

Drug Policy Alliance. 2016. Supervised injection facilities. http://www.drugpolicy.org/sites/default/files/DPA%20Fact%20Sheet_Supervised%20Injection%20Facilities%20(Feb.%202016).pdf (accessed December 6, 2016).

Eckman, M. H., T. E. Kaiser, and K. E. Sherman. 2011. The cost-effectiveness of screening for chronic hepatitis B infection in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases 52(11):1294-1306.

Edlin, B. R. 2011. Perspective: Test and treat this silent killer. Nature 474:S18-S19.

Elam-Evans, L. D., D. Yankey, J. A. Singleton, and M. Kolasa. 2014. National, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19-35 months—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 63(34):741-748.

Elefsiniotis, I., E. Vezali, D. Vrachatis, S. Hatzianastasiou, S. Pappas, G. Farmakidis, G. Vrioni, and A. Tsakris. 2015. Post-partum reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection among hepatitis B e-antigen-negative women. World Journal of Gastroenterology 21(4):1261-1267.

Everson, G. T., L. Balart, S. S. Lee, R. W. Reindollar, M. L. Shiffman, G. Y. Minuk, P. J. Pockros, S. Govindarajan, E. Lentz, and E. J. Heathcote. 2008. Histological benefits of virological response to peginterferon alfa-2a monotherapy in patients with hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 27(7):542-551.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). n.d. Information for phamacists. NDA 20-732. NDA 20-733. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm191533.pdf (accessed November 15, 2016).

Ferrante, J. M., D. G. Winston, P. H. Chen, and A. N. de la Torre. 2008. Family physicians’ knowledge and screening of chronic hepatitis and liver cancer. Family Medicine 40(5):345-351.

Forcione, D. G., R. T. Chung, and J. L. Dienstag. 2002. Natural history of hepatitis B virus infection. In Chronic viral hepatitis: Diagnosis and therapeutics, edited by R. S. Koff and G. Y. Wu. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. Pp. 41-58.

Freiberg, M. S., C. C. Chang, M. Skanderson, K. McGinnis, L. H. Kuller, K. L. Kraemer, D. Rimland, M. B. Goetz, A. A. Butt, M. C. Rodriguez Barradas, C. Gibert, D. Leaf, S. T. Brown, J. Samet, L. Kazis, K. Bryant, and A. C. Justice. 2011. The risk of incident coronary heart disease among veterans with and without HIV and hepatitis C. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 4(4):425-432.

Freiman, J. M., T. M. Tran, S. G. Schumacher, L. F. White, S. Ongarello, J. Cohn, P. J. Easterbrook, B. P. Linas, and C. M. Denkinger. 2016. Hepatitis C core antigen testing for diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine 165(5):345-355.

Galbraith, J. W., R. A. Franco, J. P. Donnelly, J. B. Rodgers, J. M. Morgan, A. F. Viles, E. T. Overton, M. S. Saag, and H. E. Wang. 2015. Unrecognized chronic hepatitis C virus infection among baby boomers in the emergency department. Hepatology 61(3):776-782.

Giles, M., K. Visvanathan, S. Lewin, S. Bowden, S. Locarnini, T. Spelman, and J. Sasadeusz. 2015. Clinical and virological predictors of hepatic flares in pregnant women with chronic hepatitis C. Gut 64(11):1810-1815.

Goad, J. A., M. S. Taitel, L. E. Fensterheim, and A. E. Cannon. 2013. Vaccinations administered during off-clinic hours at a national community pharmacy: Implications for increasing patient access and convenience. Annals of Family Medicine 11(5):429-436.

Grebely, J., B. Haire, L. E. Taylor, P. Macneill, A. H. Litwin, T. Swan, J. Byrne, J. Levin, P. Bruggmann, and G. J. Dore. 2015. Excluding people who use drugs or alcohol from access to hepatitis C treatments—Is this fair, given the available data? Journal of Hepatology 63(4):779-782.

Hagan, H., E. R. Pouget, D. C. Des Jarlais, and C. Lelutiu-Weinberger. 2008. Meta-regression of hepatitis C virus infection in relation to time since onset of illicit drug injection: The influence of time and place. American Journal of Epidemiology 168(10):1099-1109.

Hagan, H., E. R. Pouget, I. T. Williams, R. L. Garfein, S. A. Strathdee, S. M. Hudson, M. H. Latka, and L. J. Ouellet. 2010. Attribution of hepatitis C virus seroconversion risk in young injection drug users in 5 U.S. cities. Journal of Infectious Diseases 201(3):378-385.

Hammett, T. M., S. Phan, J. Gaggin, P. Case, N. Zaller, A. Lutnick, A. H. Kral, E. V. Fedorova, R. Heimer, W. Small, R. Pollini, L. Beletsky, C. Latkin, and D. C. Des Jarlais. 2014. Pharmacies as providers of expanded health services for people who inject drugs: A review of laws, policies, and barriers in six countries. BMC Health Services Research 14:261.

Harper, J. 2015. Indiana’s HIV outbreak leads to reversal on needle exchanges. NPR (National Public Radio), June 2. http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/06/02/411231157/indianas-hiv-outbreak-leads-to-reversal-on-needle-exchanges (accessed December 1, 2016).

Harris, A. M., K. Iqbal, S. Schillie, J. Britton, M. A. Kainer, S. Tressler, and C. Vellozzi. 2016a. Increases in acute hepatitis B virus infections—Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, 2006-2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65(3):47-50.

Harris, R. J., N. K. Martin, E. Rand, S. Mandal, D. Mutimer, P. Vickerman, M. E. Ramsay, D. De Angelis, M. Hickman, and H. E. Harris. 2016b. New treatments for hepatitis C virus (HCV): Scope for preventing liver disease and HCV transmission in England. Journal of Viral Hepatitis 23(8):631-643.

Havens, J. R., M. R. Lofwall, S. D. Frost, C. B. Oser, C. G. Leukefeld, and R. A. Crosby. 2013. Individual and network factors associated with prevalent hepatitis C infection among rural Appalachian injection drug users. American Journal of Public Health 103(1):e44-e52.

Henkle, E., M. Lu, L. B. Rupp, J. A. Boscarino, V. Vijayadeva, M. A. Schmidt, and S. C. Gordon. 2015. Hepatitis A and B immunity and vaccination in chronic hepatitis B and C patients in a large United States cohort. Clinical Infectious Diseases 60(4):514-522.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2013. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: Current activities and future opportunities. Washington, DC: HHS, Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee, Prescription Drug Abuse Subcommittee.

HHS. 2015. Action plan for the prevention, care, and treatment of viral hepatitis: 2014-2016. HHS, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy. https://www.aids.gov/pdf/viral-hepatitis-action-plan.pdf (accessed October 26, 2016).

HHS. 2016a. Chapter 4. Early intervention, treatment, and management of substance use disorders. Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington, DC: HHS, Office of the Surgeon General.

HHS. 2016b. Chapter 6. Health care systems and substance use disorders. Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington, DC: HHS, Office of the Surgeon General.

HHS. 2016c. Medication assisted treatment for opioid use disorders. 81 FR 44711. Federal Register 81(131):44711-44739. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/07/08/2016-16120/medication-assisted-treatment-for-opioid-use-disorders (accessed February 23, 2017).

HHS. n.d. IID-15.3: Increase hepatitis B vaccine coverage among health care personnel https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives (accessed March 1, 2017).

Holtzman, D., V. Barry, L. J. Ouellet, D. C. Des Jarlais, D. Vlahov, E. T. Golub, S. M. Hudson, and R. S. Garfein. 2009. The influence of needle exchange programs on injection risk behaviors and infection with hepatitis C virus among young injection drug users in select cities in the United States, 1994-2004. Preventive Medicine 49(1):68-73.

Hoover, K. W., M. Butler, K. A. Workowski, S. Follansbee, B. Gratzer, C. B. Hare, B. Johnston, J. L. Theodore, G. Tao, B. D. Smith, T. Chorba, and C. K. Kent. 2012. Low rates of hepatitis screening and vaccination of HIV-infected MSM in HIV clinics. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 39(5):349-353.

Hsieh, Y. H., R. E. Rothman, O. B. Laeyendecker, G. D. Kelen, A. Avornu, E. U. Patel, J. Kim, R. Irvin, D. L. Thomas, and T. C. Quinn. 2016. Evaluation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for hepatitis C virus testing in an urban emergency department. Clinical Infectious Diseases 62(9):1059-1065.

Hughes, C. 2016. New York Medicaid to cover hepatitis C treatment. Times Union, April 27. http://www.timesunion.com/local/article/Patient-group-presses-state-for-increased-7378967.php (accessed November 1, 2016).

Hulse, G. K., N. Morris, D. Arnold-Reed, and R. J. Tait. 2009. Improving clinical outcomes in treating heroin dependence: Randomized, controlled trial of oral or implant naltrexone. Archives of General Psychiatry 66(10):1108-1115.

Hutton, D. W., D. Tan, S. K. So, and M. L. Brandeau. 2007. Cost-effectiveness of screening and vaccinating Asian and Pacific Islander adults for hepatitis B. Annals of Internal Medicine 147(7):460-469.

Immunization Action Coalition. 2016. State information: States authorizing pharmacists to vaccinate. http://www.immunize.org/laws/pharm.asp (accessed December 6, 2016).

Immunization Action Coalition. n.d. Hepatitis B: Questions and answers: Information about the disease and vaccines. http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4205.pdf (accessed December 7, 2016).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1995. Treatment standards and optimal treatment. In Federal regulation of methadone treatment, edited by R. A. Rettig and A. Yarmolinsky. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Ivsins, A., C. Chow, D. Marsh, S. Macdonald, T. Stockwell, and K. Vallance. 2010. Drug use trends in Victoria and Vancouver, and changes in injection drug use after the closure of Victoria’s fixed site needle exchange. (CARBCstatistical bulletin). Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: University of Victoria.

Jackson, Y., F. Chappuis, N. Mezger, K. Kanappa, and L. Loutan. 2007. High immunogenicity of delayed third dose of hepatitis B vaccine in travellers. Vaccine 25(17):3482-3484.