6

Treatment Challenges

David Fukuzawa, managing director for health and human services at The Kresge Foundation, observed that, just as obesity is a complicated disease to prevent, it is a complicated disease to treat. Obesity may consist of a complex combination of different diseases, with treatment, especially for severe obesity, requiring more than better nutrition and physical activity, he noted. The challenges of treatment, including the limited effectiveness of current treatments, the lack of access to treatment, and the shortage of

trained treatment providers, were examined by three presenters: Caroline Apovian, professor of medicine and pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine; Fukuzawa; and Don Bradley, associate consulting professor of community and family medicine, Duke University.

NEW TREATMENTS

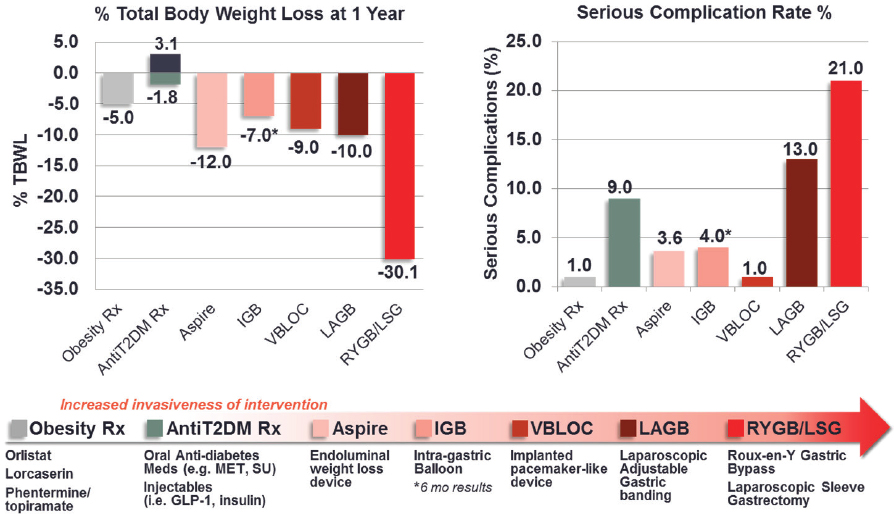

Since about 2000, the number of treatments for obesity has risen rapidly, according to Apovian (see Figure 6-1). New drug treatments can produce weight losses of 5 to 10 percent, she noted, which might translate to 25 pounds in a patient with a body mass index (BMI) over 30 who weighs 250 pounds. Surgical approaches for patients with extreme obesity have also become more numerous and safer, she reported, with weight losses of up to 30 percent (Chang et al., 2014). However, she added, the more efficacious the treatment, the higher is the complication rate, which she called “the Catch-22 about the benefits and risks of obesity treatments.”

According to Apovian, millions of patients with severe obesity are eligible for a surgical treatment, but only about 1 percent undergo such a procedure, amounting to about 200,000 procedures per year (American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, 2016; Funk et al., 2016). Similarly, only about 2 percent of the U.S. population who are eligible for a drug treatment receive it (Samaranayake et al., 2012; Xia et al., 2015).

Among the many barriers to obesity treatment are patients who do not accept the idea of surgical intervention for their weight problem and doctors who do not accept the risk of surgery for their patients, Apovian noted (Diamant et al., 2014; Funk et al., 2015, 2016; Westerveld and Yang, 2016). Additional barriers she cited include the lack of insurance coverage for drugs, the dearth of physicians who can treat obesity, and patients’ unwillingness to undergo drug treatment (Avidor et al., 2007; Forman-Hoffman et al., 2006; Funk et al., 2016; Perlman et al., 2007; Westerveld and Yang, 2016). In marked contrast with the obesity treatment guidelines released in 2013 (Jensen et al., 2014), she reported, clinicians often fail to diagnose overweight and obesity or discuss weight management with patients (Abid et al., 2005; Bardia et al., 2007; Cyr et al., 2016; Fink et al., 2014; King et al., 2015; Ko et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2009; McAlpine and Wilson, 2007). She gave as part of the reason the lack of time for each patient in a busy primary care practice (Korber, 2011; Lewis and Gudzune, 2014). She observed that physicians may also be reluctant to discuss the issue because it is so emotionally charged for many people (Wadden and Didie, 2003). And many doctors have not been trained to produce behavioral changes to treat obesity (Forman-Hoffman et al., 2006).

Apovian went on to suggest that the treatment of patients with obesity

NOTE: IGB = intragastric balloon; LAGB = laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; LSG = laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; Rx = pharmacological management; RYGB = roux-en-Y gastric bypass; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus; TBWL = total body weight loss; vBloc = neurometabolic therapy.

SOURCES: Presented by Caroline Apovian on September 27, 2016 (reprinted with permission). Data drawn from Apovian et al., 2015 (obesity Rx); Chang et al., 2014 (bariatric surgery: gastric banding, gastric bypass); Daneschvar et al., 2016 (obesity Rx); Imaz et al., 2008 (intragastric balloon); Kashyap et al., 2010 (bariatric surgery: gastric banding, gastric bypass, gastric sleeve gastroectomy); Patel, 2015 (obesity Rx); Phillips et al., 2009 (Realize gastric band); Ribaric et al., 2014 (bariatric surgery: gastric banding, gastric bypass, gastroectomy); Thompson et al., 2016 (AspireAssist).

is complicated by a range of socioeconomic, geographic, cultural, biological, and environmental differences. Beyond socioeconomic, geographic, and cultural disparities, she noted, there may be inherent physiological differences in how different racial groups develop comorbidities. With gastric bypass surgery, sleeve gastrectomy, and medications, for example, African Americans tend to lose less weight than non-Hispanic whites in clinical trials, probably because of a complicated interplay of physiological drivers, access to care, and treatment responses (Lewis et al., 2016). Apovian observed that African Americans tend to be more insulin resistant than non-Hispanic whites with similar BMIs, which may be related to a genetic or physiological difference among racial groups (Hasson et al., 2015). Other group differences exist as well. As an example, Apovian explained that typically people with mental illness have a higher risk of obesity, both because of the medications they are typically prescribed and because of their behaviors (Taylor et al., 2012).

Apovian called for inclusion of a wider range of racial and ethnic minority groups in studies of new treatments (which typically focus primarily on African Americans and non-Hispanic whites), as well as socially distinct groups (rural residents, people with mental illness, and those who have alternative lifestyles). Culturally appropriate and tailored care shows promise in the research literature, she said, but standards for such care need to be developed. Similarly, she suggested, research is needed on social and physiological factors related to treatment outcomes for nonbehavioral therapies such as medication and bariatric surgery, as are strategies for improving access to care for underserved populations (Lewis et al., 2016).

Apovian added that clinicians need more training, obesity medicine specialists need more time to work with individual patients, and approaches are needed for dealing with a lack of patient motivation to lose weight because of frequent failures or unavailability of reimbursement. Even today, she noted, BMI is generally not being added to patient charts, many scales in doctors’ offices are inadequate since they often go only to 350 pounds, and clinics may lack equipment that can accommodate larger-sized patients. Therefore, Apovian argued, improvements in training, practice-based changes, and better coverage of services, especially for those of lower socioeconomic status, all are crucial for improving capacity for the treatment of obesity (Bleich et al., 2012). She concluded by noting that preventive programs, lifestyle treatment programs, and Head Start programs that engage children and their parents are proposed targets for patients at risk or high risk for obesity and its comorbidities.

THE LACK OF PROVIDERS

The numbers on supply and demand for obesity treatment provide “a sense of just what it is we’re up against,” said Fukuzawa. The number of new board-certified physicians in obesity medicine has undergone a dramatic increase, from fewer than 400 in 2011 to about 1,600 in 2016.1 However, approximately 17.6 million U.S. adults have severe obesity, Fukuzawa noted, meaning that, at current levels of board-certified physicians, each trained obesity specialist would have to serve approximately 11,000 patients. Even if the pool of physicians able to treat obesity were considered to be all primary care physicians, he said, including family practitioners and general practice, internal medicine, and obstetrics/gynecology physicians, each physician would need to treat about 90 people with severe obesity (a BMI greater than 40) or 160 and 440 people with less severe obesity (BMIs greater than 35 and 30, respectively). Thus, he said, “we face an enormous challenge just on the treatment side.”

With regard to patient self-management, Fukuzawa observed, probably the best-known program is the YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program. From slightly more than 500 participants in 2010, the program grew to 12,600 participants in 2015.2 However, noted Fukuzawa, 86 million U.S. adults with prediabetes would be candidates for the program (CDC, 2016b). Given that the program at each YMCA currently serves an average of 57 participants, approximately 1.5 million programs would be required to reach all prediabetics—an 11,000 percent increase.

Bradley elaborated on the lack of trained obesity treatment providers. He reported that only about one-quarter of physicians say that they know enough about diet or physical activity to provide adequate care for obesity, fewer than one-eighth of physician visits include counseling for nutrition (Howe et al., 2010), and fewer than 30 percent of medical schools provide the education future physicians will need to treat patients with obesity (Adams et al., 2010). In addition, coverage for such care by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers is spotty (Petrin et al., 2014). A nutritionist or dietitian can provide care for obesity if a physician bills for it, Bradley noted, but these providers are not allowed to move forward independently. As a result, he said, “the best trained people . . . have the least ability to be paid for the services.”

Bradley also noted that only a handful of states provide Medicaid coverage for obesity drugs, whereas coverage for bariatric surgery is near 100 percent. Furthermore, he observed, the poorest coverage seems to be where the prevalence of obesity is highest (Petrin et al., 2014).

___________________

1 Personal communication, Dana Brittan, American Board of Medicine.

2 Personal communication, Emily Greenberg, YMCA of the USA.

BEYOND HEALTH CARE

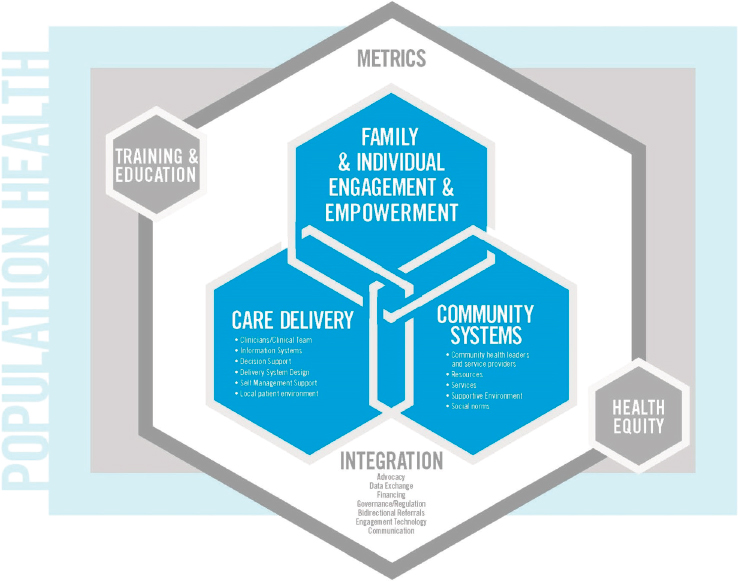

Fukuzawa briefly described a framework for integrated clinical and community systems of care (see Figure 6-2). It combines care delivery systems intended to manage and prevent obesity with community systems that can serve the same goals. The challenge, Fukuzawa said, is to connect these components through various mechanisms to achieve the greatest possible effect.

Building on this point, Bradley observed that only 10 percent of premature deaths related to the social determinants of health can be accounted for by influences from health care (Schroeder, 2007); the rest relates to behavioral patterns, social circumstances, environmental exposures, and genetics. What is needed, he asserted, is an integrated approach that entails spending a great deal more on social programs.

Apovian called for a more consistent view of obesity as a condition across health systems and the community. “Physicians are not the center of the earth,” she said. “There are a number of health professionals who

SOURCES: Presented by Don Bradley, September 27, 2016 (with permission, Dietz et al., 2017).

can provide care at least as effectively, and in some cases more effectively.” She acknowledged, however, that the primary care physician will continue to be the gatekeeper for exercise physiologists, dietitians, social workers, psychologists, and others. Multidisciplinary practices can provide these specialists, even as primary care physicians are overseeing the treatment plan, she suggested. An interesting question, for example, is how the YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program could be scaled up and used in a multidisciplinary program. “We’re never going to have enough obesity medicine specialists, certainly in the next 20 years,” Apovian argued, “to start pushing back on this problem. We need to develop programs like that.” One extension she suggested is developing an Internet-based video version of the program for patients who do not want to travel to the YMCA, although she acknowledged that some patients in underserved areas lack access to the Internet.

Another extension, suggested Bradley, could be to work through provider groups (i.e., accountable care organizations) or the community to deliver such services in more creative ways, such as through local churches or community centers. What this would do, he explained, is help focus on outcomes, with fewer rules as to who can deliver services. As a more specific suggestion, he noted that his students experienced a tremendous response from African American barber shops when they went into the community to work on health issues.

This page intentionally left blank.