5

Physical Activity

Approaches to driving significant progress in preventing and treating obesity through physical activity were examined by four speakers: James

Sallis, distinguished professor of family medicine and public health, University of California, San Diego; Harold (Bill) Kohl, professor of epidemiology and kinesiology, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston School of Public Health, and The University of Texas at Austin; Christina Economos, co-founder and director of ChildObesity1801 and professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University; and Arnell Hinkle, founding executive director of Communities, Adolescents, Nutrition, and Fitness (CANFIT). These speakers emphasized promising interventions and approaches to their implementation, the translation of research into practice, and equity.

INTERVENTIONS TO INCREASE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

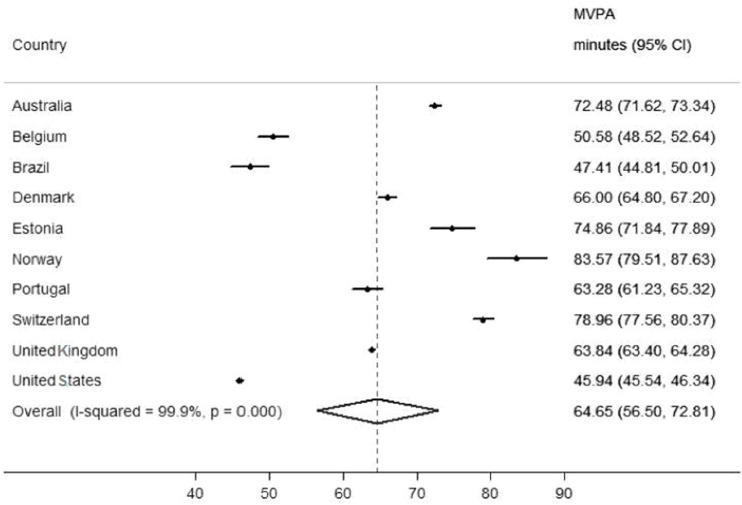

Sallis began by noting that U.S. children overall are among the least physically active in the world. In a comparison of moderate to vigorous physical activity among young people in 10 countries, based on objective monitors, the United State scored lowest, at 46 minutes, compared with an average of 65 minutes and a top level (in Norway) of almost 84 minutes, nearly twice the U.S. average (Hallal et al., 2012) (see Figure 5-1). “Our children are just not active enough,” asserted Sallis. The same general pattern is seen among adults, he reported, with fewer than 50 percent of U.S. adults meeting the 2008 federal guidelines for aerobic activity based on self-report (although the percentage has risen somewhat over the past decade) (NCHS, 2016). Disparities also mark levels of physical activity, he added, with the percentage of those meeting the guidelines being higher for men than for women, declining with age, and being lower for blacks and Hispanics than for whites (NCHS, 2016).

Fortunately, Sallis noted, the National Physical Activity Plan,2 which was revised in 2016, provides a comprehensive set of policies, programs, and initiatives designed to increase physical activity in all segments of the U.S. population. The plan organizes recommended actions into nine sectors:

- business and industry

- community, recreation, fitness, and parks

- education

- faith-based settings

- health care

- mass media

- public health

- sport

- transportation, land use, and community design

___________________

1 See www.childobesity180.org (accessed January 17, 2017).

2 See www.physicalactivityplan.org (accessed January 17, 2017).

SOURCES: Presented by James Sallis on September 27, 2016 (reprinted with permission, Hallal et al., 2012).

Furthermore, Sallis continued, effective interventions to increase physical activity have been identified. He cited a review of strategies for increasing physical activity among youth that found sufficient evidence for multicomponent school programs and physical education; suggestive or emerging evidence for active transportation to schools, activity breaks in classrooms, strategies in preschool and child care settings and the built environment; and insufficient evidence for school physical environments, after-school programs, home and family influences, and programs in primary care settings (Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Midcourse Report Subcommittee of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports & Nutrition, 2012).

Sallis emphasized that no one intervention will be sufficient. He cited the Institute of Medicine report Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School (IOM, 2013), which recommends a whole-of-school approach and reinforces the value of a multicomponent school program. As an example, he pointed to a study of about 100 elementary schools in San Diego County and Washington State (Carlson et al., 2013). Accelerometer data revealed that children in schools

with more physical activity–supportive practices3 engaged in significantly more minutes per day of moderate to vigorous physical activity in school relative to children in schools with fewer such practices. Children in schools with the fewest such practices (zero to one) engaged in just 21 minutes of activity during the school day, compared with 41 minutes per day in schools with the most (four to five). In particular, Sallis reported, providing more than 100 minutes of physical education per week, having recess periods of 20 minutes or longer, and having a physical education specialist were positively associated with increasing moderate to vigorous activity in school. Disparities appear in these data as well, Sallis noted. According to Carlson and colleagues (2014), the practice with the largest disparity by school socioeconomic status was having a physical education specialist, which is less likely in low-income than in high-income schools.

More evidence for the existence of effective interventions and the benefits of multiple approaches comes from early care and education, noted Sallis. A meta-analysis of 43 studies quantified the strength of obesity prevention interventions, defined by number of strategies, intensity, frequency, and duration, in early care and education settings (Ward et al., 2016). Sallis observed that a summary indicator of intervention strength was positively correlated with reporting of positive anthropometric outcomes (e.g., body fat, body mass index), while the addition of parent engagement components increased the strength of these relationships. “The stronger the intervention, the more likely it was to be effective in reducing or slowing down weight gain,” said Sallis. “That’s good news in early child care and education,” he added. “The most intensive interventions that are being evaluated do seem to work.” The key, he said, is translating research into practice.

Multicomponent policy and environmental interventions are challenging and can be costly to deliver, Sallis acknowledged, but having an impact on children’s health depends on finding a way to overcome these challenges. “How can we be more effective in attracting commitment and support for these approaches in schools and early care settings from education decision makers?” he asked. One answer, he said, is the new federal education bill, the Every Student Succeeds Act,4 which makes more funding available for school physical activity. Another is wider and more equitable distribution of school funds for sports, he argued. For example, he noted, a few schools have essentially eliminated their interscholastic sports programs and used those resources to greatly expand intramural programs that are open to

___________________

3 Such practices included, for example, having a physical education teacher, providing more than 100 minutes/week of physical education, having recess supervised by personnel other than classroom teachers, providing more than 20 minutes/period of recess, and having no more than 75 students/supervisor in recess (Carlson et al., 2013).

4 See https://www.ed.gov/essa?src=ft (accessed January 30, 2017).

all students, who thereby have more opportunities to be physically active. Evaluations of this approach have pointed to more widespread activity, particularly for African American students (Kanters et al., 2013). “That’s a revolutionary approach that could redistribute the same funds for greater benefits while reducing health disparities,” Sallis asserted.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MULTIPLE APPROACHES

Like Sallis, Kohl emphasized the importance of taking multiple approaches to preventing obesity. As he pointed out, even in the best physical education programs, children tend to be active for no more than 10 or 15 minutes. “If 60 minutes is the recommendation,” he said, “then we have a bunch of work to do.”

According to Kohl, an especially promising approach is to consider physical activity in all policies related to schools. Such policies can extend from birthday parties to siting schools so as to facilitate active transport. “We have to think more about the systems in which our children live,” Kohl asserted. “They [encounter] the health sector, the transportation sector, the education sector, and the recreation sector virtually every day. How do we make those more accessible and make them relevant for participation in physical activity?”

Kohl also advocated making physical education a core subject like mathematics or reading and having a federally determined provision for measuring it. The drive to increase test scores of recent years has been forcing schools to have their students spend more time in class, but as he pointed out, physical activity plays an important role in cognitive development and academic performance. He believes all classroom teachers and administrators, not just physical education instructors, should receive preservice as well as in-service training in physical education. “We may be holding test scores down by keeping kids more sedentary in class,” he suggested. “Active kids learn faster, and they remember more, than their inactive counterparts.” He argued that measuring physical activity and its effects on academic achievement could help make the case for a more intensive effort.

Kohl advocates reducing disparities in access. Schools without adequate physical education, which are predominantly in low-income communities, are “unacceptable from a public health standpoint,” he said. He cited reducing disparities as the cornerstone of public health, and argued that advocates in schools, on school boards, and on state boards of education all can influence policies that affect disparities.

TRANSLATING RESEARCH TO PRACTICE

Economos began by observing that a critical factor in the success of evidence-based programs is translating research to practice. As an example, she cited a study of the factors within schools that have enabled them to institute multicomponent physical activity programs (Economos, in press). Survey and interview data on 23 geographically and economically diverse U.S. school districts that had been nominated as exemplars in providing physical activity and physical education to their students revealed that they offered more opportunities (in terms of minutes) for physical education and recess per week compared with a nationally representative sample of school districts. Furthermore, Economos noted, the exemplar school districts provided a high number of physical activity programs in addition to physical education and recess opportunities. “Think about a school bringing in a walking–running program, a classroom (physical activity) break program, and a dance program,” she said. Schools that implemented a rich portfolio of programs to get their students up and moving were especially successful, she reported.

Economos suggested that the presence of champions for physical activity, adequate resources, and collaboration with stakeholders in the community are important for implementing a multicomponent physical activity program in schools. However, she noted, “there are a lot of communities out there that haven’t been able to do that. How do we provide the resources, the inspiration, and the training to get other communities to do the same programming and get kids up and moving?” she asked.

Economos closed by arguing that more work is needed in the areas of dissemination, implementation, and translation. “We have really good recommendations and policies,” she observed. “How do we actually put them into schools and communities and make sure that they are sustained over time?”

WALKING AND WALKABILITY

Turning specifically to the issue of walking and walkability, Sallis cited the surgeon general’s 2015 Call To Action report on the subject (HHS, 2015). The number of people who walk for transportation in the United States is “pretty low,” he said—around 30 percent (Paul et al., 2015). Walking for leisure is slightly more popular, but still only 40 to 50 percent of people engage in this most common physical activity, he noted, with some disparities among population groups. He observed that those percentages are related in part to walkability—the design of a community so that people can walk from their home to other places they might want to go. In an international study of 12 countries around the world, he noted, the lowest

walkability indexes among the cities studied were for four cities in New Zealand and two regions in the United States (in and around Baltimore and Seattle) (Adams et al., 2014). The walkability index included such factors as residential density, the connectivity of the street network, and mixed use or having destinations nearby. “We are among the least walkable countries in the world,” said Sallis.

Once a city has been laid out, Sallis continued, changing it is difficult, but short-term approaches are still possible. One such approach is to change the details of the streetscape to encourage walking by adding housing, stores, crosswalks, trees, and other amenities. Using a tool called Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes (MAPS) Mini5 that Sallis and his colleagues developed, streets can be measured for their friendliness to activity on such measures as public parks, streetlights, benches, sidewalks, the absence of graffiti, trees, marked crosswalks, curb cuts, and crossing signals (Sallis et al., 2015). Sallis reported that the quality of streetscapes was positively related to walking for transport, from children through older adults (Sallis et al., 2015). “This shows that the quality of the built environment can matter,” he said.

According to recent studies, Sallis noted, low-income communities do not necessarily show consistent environmental disparities (Engelberg et al., 2016; Thornton et al., 2016). In some cases, he said, there are “equitable differences” across communities, with the quality of streetscapes or parks being significantly better in low-income or high-minority neighborhoods. According to Sallis, these data suggest that local policies can be effective in creating more equitable built environments. Given each city’s unique pattern of environmental disparities, he suggested, it is necessary to assess local conditions as a basis for remediating disparities in physical activity environments.

BUILDING IN EQUITY

Hinkle has been working with community-based organizations to promote physical activity for more than two decades, with a particular focus on equity. CANFIT operates on the belief that “equality” is not the same as equity. As an example, she noted that equality may be getting a park in every low-income neighborhood, but “if you build it, it doesn’t mean that they’re going to come.” People need to feel invited and welcome, she asserted, and a park or other resource needs to provide them with something they want to do. Thus, she suggested, “the equity piece is more about finding out what people want to do to be active, what their interests are,

___________________

5 See www.activelivingresearch.org/microscale-audit-pedestrian-streetscapes (accessed January 12, 2017).

building community capacity around that, and involving residents in the process.” She pointed to a model known as PROGRESS Plus6 in which the design and implementation of programs take into account places of residence, race, ethnicity, culture, occupation, gender/sex, religion, education, socioeconomic status, social capital, age, and disability. “To be equitable, you have to think about all of those factors,” she said. Examples of physical activity projects that reflect the PROGRESS Plus model include the “Walk with Friends” project in Sacramento7 and an interesting experiment under way in Denmark to redesign the entire school system to be more of an active learning environment.

According to Hinkle, an important issue to remember in efforts to build in equity is that the goal should be lifelong physical activity. Activities need to be “fun, enjoyable, something that people want to do, and are able to continue doing throughout their lives,” she argued, suggesting that dance, yoga, swimming, and other activities can teach people how to be active for longer spans of time. Especially among children older than 10, she noted, community time tends to be critical, not just school time or the time spent learning a team sport. Student athletes have a tendency to overwork their bodies and end up injured, she observed, so that they cannot engage in the activities they learned to do and become sedentary later in life. Focusing on injury prevention and proper body mechanics can help people perform activities correctly, she said, which will “serve them better over the long haul.”

As an additional issue to consider when thinking of solutions for improving access to physical activity opportunities, Hinkle cited the role of violence and physical safety in the community. Violence is a factor in some settings, she noted, such as a park where violent gang activity is common. She emphasized that neighborhood involvement can lead to such activities as walking groups that build cultural norms around activity and take back public spaces.

Message framing is critical to increasing equitable implementation of physical activity resources, Hinkle argued. “We come up with policies and recommendations that people should do,” she said, “but they often don’t know how to implement them.” As an example, she suggested that instead of emphasizing weight loss as the primary benefit of physical activity, it would be better to highlight the wide range of benefits that result from being active, including social support, reduced stress, greater longevity, and improved mobility. “For a lot of people, weight loss is not going to be the hook,” she suggested. It’s going to be the other benefits.”

Hinkle concluded by citing important questions to consider when de-

___________________

6 See http://www.nccmt.ca/resources/search/234 (accessed January 30, 2017).

7 See https://healthedcouncil.org/events (accessed January 30, 2017).

veloping physical activity programs: Who benefits? Who pays? Who is harmed? Who leads? Who decides what a program includes? Who speaks up for it? Who funds it? How much is funded?

THE ROLE OF COMMUNITIES

An issue that arose in the discussion session was the role of communities in building momentum for change involving physical activity. Many decisions about transportation, land use, and school policies are made at the local level, Sallis noted, and when leaders from inside and outside of government create a shared vision, change can happen. Leadership, he suggested, is critical because multiple city agencies need to work together to create more activity-friendly communities. “Leadership makes it happen most of the time,” he said, “and community input probably makes it better; but I haven’t seen it come too often just from the ground up.” The risk of grassroots efforts, he continued, is that consensus is very difficult when so many different voices come together to work on a plan. “What we need is educated and informed input, . . . where scenarios are created and consequences are discussed,” which, he argued, requires both research and good community engagement.

Kohl elaborated that finding a champion for a program is not enough; rather, a broader demand for equitable programs to promote physical activity needs to be developed. “Grassroots, bottom-up demand has to be leveraged,” he asserted. “It just takes a few people to start that ball rolling.”

Hinkle observed that several of the initiatives she discussed had committed explicitly to authentic community engagement. “Just like in research,” she noted, “you can have good community engagement; you can have bad community engagement.” She suggested that sustainable programs are successful because they engage and educate community members. As a result, the community has the skills and resources necessary to lead and advocate for its own physical activity environment.

Communities not only can be sources of advice and advocacy but also can take a leadership role in developing more opportunities for physical activity, Sallis added. Getting children active is not cost free, he noted. “I would like to see, especially in low-income areas, more creative solutions to providing activities in local parks or elsewhere in the neighborhood,” he said. “There may be ways of doing this that help with economic development, too. If there were small grants, where people from the neighborhoods would compete to get little contracts to provide activities within the neighborhoods. . . . I think you can have multiple wins by doing things like that.”

This page intentionally left blank.