5

Moving Forward

On the second day of the workshop, in Session 4, moderated by Johanna Dwyer, senior nutrition scientist, Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), the focus of discussion shifted to the future and ways to promote healthy aging. First, David Reuben, director, Multicampus Program in Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, and chief, Division of Geriatrics, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), provided an overview of results from observational studies and clinical trials on three diets and their effects on health in older individuals: (1) the Mediterranean diet, (2) the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, and (3) the MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet. Next, Eve Stoody, lead nutritionist of nutrition guidance, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (CNPP), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), provided an overview of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), discussed dietary intake across the lifespan, and highlighted opportunities for the future. Finally, Timothy Morck, president and founder, Spectrum Nutrition LLC, and Douglas “Duffy” MacKay, senior vice president, scientific and regulatory affairs, Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN), discussed the role of the food industry in supporting healthy aging.

NUTRITION TO PROMOTE HEALTHY AGING1

Based on his experience working with geriatric patients, Reuben emphasized the heterogeneity of the older population with respect not only to health but also to risks associated with malnutrition (e.g., being heavier may actually be beneficial for some older individuals; see the summary of Gordon Jensen’s presentation in Chapter 3), as well as barriers to good nutrition (e.g., loss of teeth, chronic diseases with dietary restrictions, medications that interfere with appetite).

Focusing on barriers to good nutrition, Reuben mentioned that some activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, such as going shopping and feeding oneself, become more difficult as one grows older and frailer, and loss of teeth makes it difficult to eat (see the summary of Athena Papas’s presentation in Chapter 4). As an example of a chronic disease associated with dietary restriction, he mentioned a patient of his with kidney disease whose potassium keeps rising and who is not eating much. He said he does not want to restrict her dietary intake given that she is already not eating much. “But she really can’t eat foods containing potassium,” he said, “or else she’s going to wind up in the hospital.” Finally, although medications administered to older adults occasionally cause weight gain, he observed, most interfere with appetite.

Additionally, Reuben emphasized variation in nutritional health among subpopulations. While healthier older people may have the same nutritional needs they had in mid-life, many others have chronic diseases or are frail and have limited life expectancy. Finally, he noted, whether older adults live in the community, an assisted living facility, or a nursing home can also affect their nutritional health, as can the extent to which individuals in any of these environments go in and out of hospitals. The nutritional requirements of each of these populations in each of these environments are different, he observed.

Three Diets and Their Effects on Health in Older Individuals

The majority of Reuben’s presentation revolved around results from observational studies and clinical trials on three diets and their effects on health in older individuals: (1) the Mediterranean diet, (2) the DASH diet, and (3) the MIND diet. He began by describing each of these diets. He noted that while the Mediterranean and DASH diets have much in common, there are some differences. Whereas the DASH diet recommends high intake of low-fat dairy, for example, the Mediterranean diet recommends low intake of full-fat dairy. Fish is classified differently in the two diets as

___________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Reuben.

well (the DASH diet recommends low fish intake, whereas the Mediterranean diet recommends high fish intake). But by and large, Reuben said, the two diets share many of the same principles. The MIND diet, which bills itself as a blend of the DASH and Mediterranean diets, is operationalized a little differently, he noted, with more nuts and berries and some foods in the DASH and Mediterranean diets not being included.

Results from Observational Studies

Reuben reported that most observational studies of these three diets have been cohort studies that have relied on dietary questionnaires, food frequencies, and similar tools. For the Mediterranean and DASH diets, he said, observational data have shown significant decreases in several adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease (9 percent reduction); cancer (with measured effects varying from 6 to 10 percent overall, based on two separate meta-analyses, to a 14 percent reduction for colorectal, 4 percent for prostate, and 56 percent for pharyngeal/esophageal cancer); overall mortality (9 percent reduction); and Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases (13 percent reduction) (Schwingshackl and Hoffman, 2014; Sofi et al., 2008). He added that a number of other studies have shown multiple effects of these diets on a range of other outcomes, from chronic kidney disease to depression.

Reuben reported that observational data for the MIND diet have shown less decline in several cognitive outcomes relative to the other two diets, based on a 4.7-year cohort study on a group of individuals at risk for dementia (Morris et al., 2015). These individuals were not prescribed a MIND diet, he explained; rather, they followed one. Results at 4.7 years showed less decline in global, episodic, semantic, and working memory; perceptual speed; and perceptual organization. Most impressively, in Reuben’s opinion, the MIND dieters were less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease at 4.5 years (Morris et al., 2015).

Results from Clinical Trials

According to Reuben, clinical trial data on these diets have similarly shown significant reductions in adverse health outcomes. The PREDIMED study of the Mediterranean and DASH diets is probably the most “famous” clinical trial of any of these diets, he remarked. Individuals aged 55-80 were randomized into three arms: (1) Mediterranean diet plus extra virgin olive oil, (2) Mediterranean diet plus mixed nuts, and (3) regular diet with reduced dietary fat (the control). The primary outcome was a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death at 4.8 years poststudy. Results showed a 28-30 percent reduction in this primary outcome

in the two experimental arms relative to the control group (Estruch et al., 2013). Reuben noted that the effect size was the same among young older persons (less than 70) and old older persons (70 and above). He also cited data from other clinical trials showing that the DASH diet lowered blood pressure and cholesterol as well (Siervo et al., 2015).

Reuben reported on a secondary analysis of PREDIMED data focused on cognition outcomes, which showed that the same interventions were also associated with higher cognitive functioning at 6.5 years poststudy (specifically, higher Mini Mental State Examination [MMSE] and Clock-Drawing Test scores) (Martínez-Lapiscina et al., 2013). Additionally, he noted, a short-term randomized clinical trial of the DASH diet showed greater psychomotor skills at 4 months (Smith et al., 2010).

Nutritional Supplements and Disease Outcomes in Older Individuals

Next, Reuben summarized some of what is known about the relationship between nutritional supplements and disease outcomes in older individuals.

Recommendations for Vitamin D and Calcium Supplementation

Reuben cited conflicting recommendations with respect to vitamin D and calcium supplementation. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) makes no recommendation. (Nor does the USPSTF make any recommendations for any vitamin, mineral, or multivitamin supplements to prevent heart disease, or for beta carotene or vitamin E.) The Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011), by contrast, recommended 800 international units of vitamin D3 daily and 1,200 mg of calcium daily for individuals aged 71 and older. Reuben noted that the IOM recommendation is the more commonly cited one.

Evidence on the Effects of Calcium Supplementation

Reuben explained that the controversy over calcium supplementation revolves around its actual effects when used as a supplement, as opposed to increasing calcium intake through the diet, which he noted may have different effects. Data from the Women’s Health Initiative showed no increased risk for either heart attack or stroke with calcium supplementation (Hsia et al., 2007), he said. However, a meta-analysis did show a slightly increased risk, with a relative risk (RR) of 1.27 for calcium alone and an RR of 1.24 when calcium supplementation was combined with vitamin D (Bolland et al., 2010, 2011).

In August 2016, Reuben continued, a small observational study con-

ducted in Europe was published in Neurology. An odds ratio (OR) of 2.10 for dementia was reported among individuals taking calcium supplements, and the OR for stroke-related dementia was 4.4 and 6.77 among individuals with a history of stroke, compared with women not receiving supplementation (Kern et al., 2016).

Evidence on the Effects of Multivitamins

Turning to the effects of multivitamins, Reuben reported that observational data from the Women’s Health Initiative in postmenopausal women showed no benefit or protective effect on breast, colorectal, endometrial, lung, or ovarian cancers; myocardial infarction; venous thromboembolism; or mortality (Mursu et al., 2011). In middle-aged men, he observed, a meta-analysis of clinical trial data indicated that multivitamins have not been shown to decrease cardiovascular disease or mortality, but have been shown to be associated with a small reduction in total cancer risk (Macpherson et al., 2013). Additionally, he said, several clinical trials conducted in nursing homes or outpatient settings have shown no benefit of multivitamins in reducing infections.

Evidence from the AREDS2 Trial

Reuben cited results from the AREDS2 trial, which came out in 2015, showing no benefit of fatty acids (docosahexaenoic acid [DHA] and eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA]), antioxidants (lutein and zeaxanthin), or zinc supplements with respect to cognitive decline (Chew et al., 2015). He explained that this study was not focused on health but on vision and prevention of the progression of macular degeneration. While conducting the study, however, the researchers ran a large set of cognitive tests. Unfortunately, in Reuben’s opinion, “any way you sliced it,” the results of the cognitive tests showed no improvement from these supplements.

QUESTIONS FOR THE FIELD

Finally, Reuben raised several questions for the field:

- How can the DGA that apply to older persons be promoted and included in prevention and health care settings? Reuben observed that “almost nothing” is going on in health care settings with respect to advising older adults on nutrition.

- How can the barriers to good nutrition that are unique to older persons be overcome? Reuben referred to his earlier description of the various settings and populations of older adults. He mentioned

- some nursing homes that will not even accept patients without gastrostomy tubes because of the cost of labor required to feed people.

- Is evidence for the Mediterranean and DASH diets compelling enough for these diets to be implemented widely, and if so, what would be the best strategy? Reuben suspects that very few people are aware of these diets and that most people would probably guess they are weight-loss strategies.

- What can be recommended for people for whom these diets would not be appropriate (i.e., those whose life expectancy is 3-5 years or less, who are extremely frail, or who have multiple chronic diseases)?

- What is the appropriate stance on multivitamins and other nutritional supplements for which evidence of benefit does not exist? Reuben remarked that many of his patients take as many nutritional supplements as they do medications. In his opinion, an enormous amount of money is being spent on nutritional supplements with no benefit.

- When, if ever, is it reasonable to stop preventive nutritional measures? Reuben said he has a number of patients who have “graduated” into the category of “eat whatever you want.” The greater issue for them is not nutrition, but consuming any calories at all.

- What more needs to be known? What would the research agenda be for older people and nutrition? What kinds of studies need to be done in these populations with respect not only to creating new knowledge but also to applying what is known? Reuben suspects that some areas are ready for implementation science, while others would benefit from more epidemiological and clinical trial data.

QUESTIONS FROM THE AUDIENCE

Following his talk, Reuben fielded questions from the audience on a range of topics. He was asked to elaborate on how much evidence exists to indicate when preventive nutrition measures should be stopped. In his opinion, this frame of thinking needs to shift when an individual’s remaining time is no longer indefinite. Up to that point, he said, while it is known that certain foods are better than others, this knowledge is not very precise. That said, there is a knowledge base on preventive nutrition measures, and it is an increasingly good one in his opinion. He believes the field has gotten closer to conducting a public education campaign (e.g., so that people know about the Mediterranean and DASH diets) and implementing these interventions. Moreover, he suggested, now is a good time to do this, as people are beginning to pay attention to nutrition.

When asked whether the benefits of the Mediterranean and DASH diets derive from what those diets add or what they reduce, Reuben replied that

he thinks reducing red meats and high-fat foods is probably what matters most. Based on his own living as a vegetarian, he commented on how difficult it can be to eat a vegetarian diet. He commented that he has had to walk out of restaurants because of the lack of menu items he would eat.

There was some discussion around supplements. Simin Meydani, workshop participant, remarked that meta-analysis results have shown that supplementation with vitamin E below 200 mg/day not only causes no harm but may have some benefit in lowering mortality. She suggested that perhaps the recommendation for vitamin E supplementation should be dose-dependent. Reuben agreed that finding an appropriate dose for some of these supplements may involve “threading the needle.” He mentioned a study showing that supplemental vitamin E doses of 1,000 mg twice daily slowed cognitive decline.

When asked about the multiple medicines being prescribed for older adults, Reuben suggested that the challenge is not only that many medicines interact with each other but also that taking that many pills per day is difficult. Remembering to take 8, 10, or 12 different medicines every day, for example, can be challenging.

MacKay remarked that, while he appreciated looking at supplements through the lens of reducing disease risk, he believes that not underscoring the importance of just meeting targeted nutrient intakes independently of disease prevention is like “throwing the baby out with the bathwater.” He added that in his opinion, results of the Physicians Health Study II, which showed a statistically significant 8 percent reduction in total cancer associated with taking a daily multivitamin, had been downplayed. Reuben replied that his intention was not to criticize the supplement industry. He said he often recommends supplements and acknowledged that some people are not getting enough of their basic vitamins from their diet and would benefit from a multivitamin. On the other hand, he believes that people who have a good diet probably get all the vitamins and minerals they need from their diet.

The last question was on recommendations for research, education, and communication to help promote healthy aging through nutrition. Reuben replied that doctors like to prescribe pills. “It is incredibly gratifying,” he said. He suggested that this same approach be considered for nutrition; that is, physicians should be able to prescribe certain types of diets to their patients, who would then get these prescriptions filled not by a pharmacist but by a nutritionist. Importantly, he said, this would have to happen at the level of the primary care physician. If primary care physicians do not have respect for good nutrition and are unaware of what it can do for a patient, he argued, they are not going to prescribe a certain type of diet—they are going to prescribe a medicine. The problem starts, in his opinion, in medical education. He described the culture, or mindset, of physicians as different

from that of those who teach nutrition. Moderator Johanna Dwyer added, “And we must not forget the nurses.”

PATTERNS OF DIETARY INTAKE ACROSS THE LIFESPAN AND OPPORTUNITIES TO SUPPORT HEALTHY AGING2

Stoody emphasized that lifespan is at the core of the 2015-2020 DGA (HHS and USDA, 2015). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and USDA, she reported, have been working together since 1980 to release new editions of the DGA every 5 years. The 2015-2020 edition was released in January 2016. Stoody explained that the current edition includes 5 guidelines and 13 recommendations and is 144 pages long. As in past editions, she added, it continues to refer to individual components of the diet, but with an increased focus on dietary patterns as a whole and their adaptability based on age, sex, physical activity level, preferences, and other factors. She quoted from Chapter 1 of the guidelines (HHS and USDA, 2015, p. 14): “The goal of the Dietary Guidelines is for individuals throughout all stages of the lifespan to have eating patterns that promote overall health and help prevent chronic disease.” Additionally, she noted, the first of the five guidelines is to “follow a healthy eating pattern across the lifespan.”

A key recommendation of the 2015-2020 DGA, Stoody pointed out, is to follow a healthy eating pattern that accounts for all food and beverages within an appropriate calorie level. The guidelines define a healthy pattern as one that includes a variety of vegetables from all subgroups (dark green, red and orange, legumes [beans and peas], starchy, and other); fruits, especially whole fruits; grains, at least half of which are whole grains; fat-free or low-fat dairy, including milk, yogurt, cheese, and fortified soy beverages; a variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), nuts and seeds, and soy products; and oils. Additionally, a healthy pattern limits saturated and trans fats, added sugars, and sodium. There are some specific quantitative recommendations for components of the diet that should be limited, Stoody noted: to consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from added sugars; to consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from saturated fats; to consume less than 2,300 mg per day of sodium (or the age-appropriate dietary reference tolerable upper intake level); and, if alcohol is consumed, to consume it in moderation (up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men), and only if one is an adult of legal drinking age.

___________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Stoody.

Meeting the DGA Recommendations: Variation Across the Lifespan

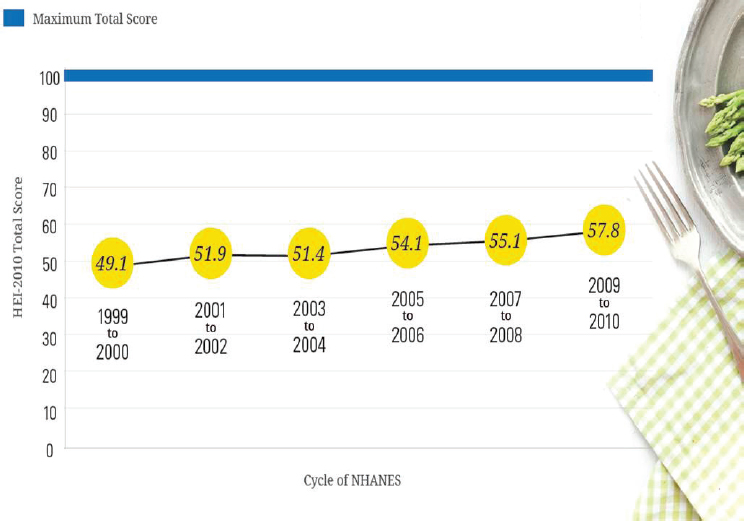

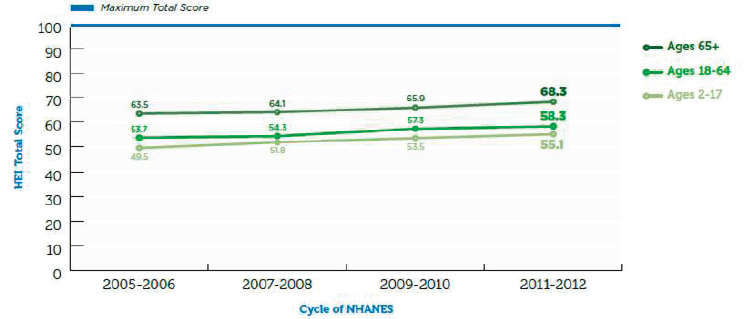

“So how are we doing in meeting these recommendations?” Stoody asked. Based on measures of the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) over the last several cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES),3 among individuals aged 2 years and older, average HEI scores had reached only 57.8 (with a maximum score being 100) by 2009-2010 (see Figure 5-1). “There is obviously a lot of room for improvement,” Stoody said. Breaking these HEI data down by age group, she noted, reveals some variability among those aged 2-17, 18-64, and 65 and older (see Figure 5-2).

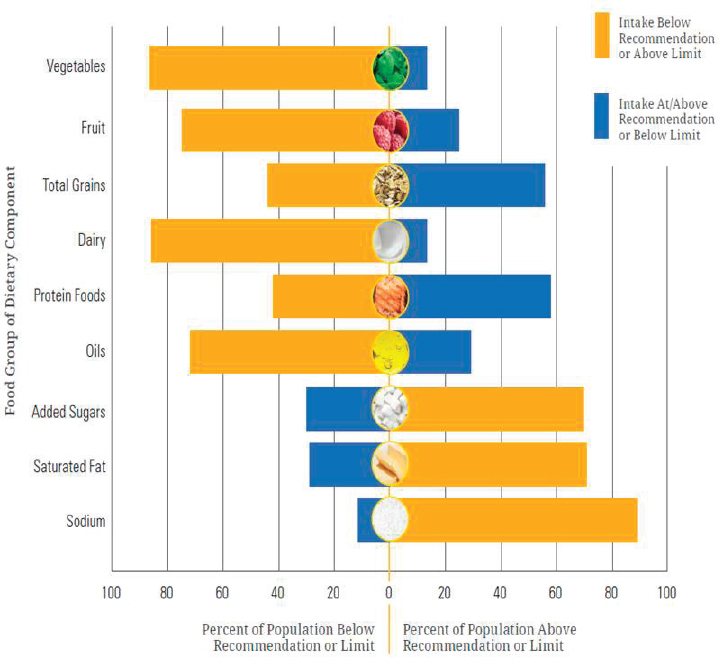

In addition to looking at measures of the total diet (i.e., HEI), Stoody suggested examining individual components of the diet separately and the percentage of the U.S. population aged 1 year and older at, above, or below each dietary goal or limit (see Figure 5-3). Again, she observed, a large percentage of the American population does not meet these recommendations. As an example, she pointed out that almost 90 percent of the population fails to meet the recommendation for vegetables. The percentage of the population meeting the recommendation for fruit is slightly better. But about 70 percent of the population is not meeting the recommended limits for added sugars and saturated fats, and an even greater percentage are not meeting the recommended limits for sodium.

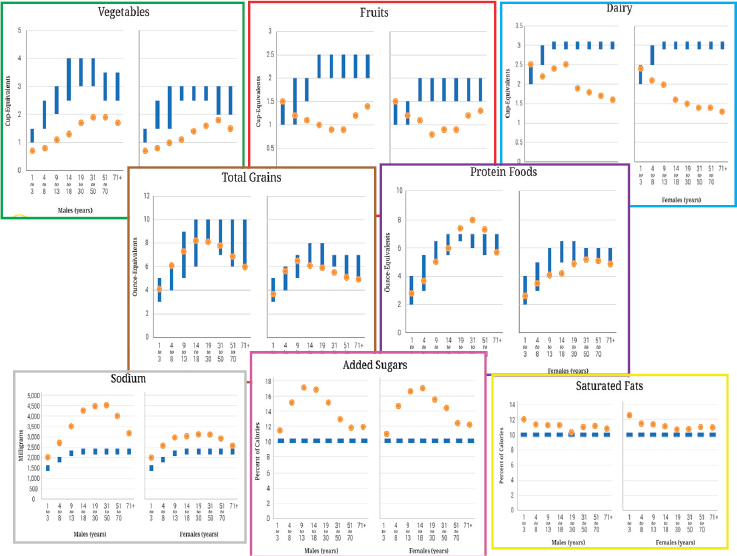

Stoody then considered several selected dietary components separately (i.e., vegetables, fruits, dairy, total grains, protein foods, sodium, added sugars, and saturated fats). She examined average daily intakes of these components across the lifespan for both sexes and compared these with recommended intakes (see Figure 5-4). She emphasized that at some stages of the lifespan, certain components of the diet are of greater concern relative to other stages of the lifespan. For example, she pointed out, average intakes for the age group 1-3 years generally fall either within or near the recommended ranges for most food components. In adolescence (ages 14-18), in contrast, vegetable and fruit intake is low for both females and males, dairy intake is particularly low for females, and intake of added sugars is high for both females and males. Among older adults (age 71 and above), while vegetable and fruit intakes are still low, the gap between these intakes and recommended levels is not as great as it is among younger individuals, and intakes of total grains and protein are near recommended levels. And added sugars and sodium are not as great a concern as with younger age groups.

In summary, Stoody said, most Americans need to shift their dietary

___________________

3 The NHANES is a repeated cross-sectional survey conducted annually that provides population-level estimates of dietary intake and trends.

SOURCES: Presented by E. Stoody, September 14, 2016. HHS and USDA, 2015.

SOURCES: Presented by E. Stoody, September 14, 2016. USDA, 2017.

SOURCES: Presented by E. Stoody, September 14, 2016. HHS and USDA, 2015.

intakes to achieve healthy eating patterns. She noted that while some of these needed shifts are minor and can be accomplished by making simple substitutions, others will require greater effort to accomplish. Finally, young children and older Americans are generally closer to the recommendations relative to adolescents and young adults.

The Future of the DGA

With respect to opportunities for future work, Stoody emphasized three areas: (1) implementation of the current DGA, (2) recommendations in future DGA, and (3) future research.

Regarding implementation of the DGA, Stoody referenced the graph

SOURCES: Presented by E. Stoody, September 14, 2016. HHS and USDA, 2015.

in Figure 5-2, which shows HEI trends over time for three different age groups, and suggested that improving the intakes of young children and maintaining those intakes as children grow into adolescence could result in healthy eating patterns across the lifespan. The question, though, is how. Stoody recalled some discussion from the previous day around the reality that simply telling people they need to eat healthier is not working. In her opinion, a much bigger conversation is necessary. As the DGA state, “Everyone has a role in helping to create and support healthy eating patterns in multiple settings nationwide, from home to school to work to communities.” Stoody noted that the DGA include a socioecological model that covers multiple areas in which change can be supported not just at the individual level but also among sectors, settings, and different social and cultural values and norms.

One of the ways in which change is supported through the federal government, Stoody continued, is through MyPlate. She remarked that a number of materials are available through ChooseMyPlate.gov to support healthy eating, including tailored, audience-specific resources for different stages of life (i.e., preschoolers, youth, older individuals). She mentioned the considerable collaborative work on promoting MyPlate, including an initiative in collaboration with the National Institute on Aging to create materials such as “10 healthy eating tips for people age 65+.”4 She noted that the National Institute on Aging’s Go4Life program has additional materials to help support healthy eating in specific settings beyond individual behavior change.

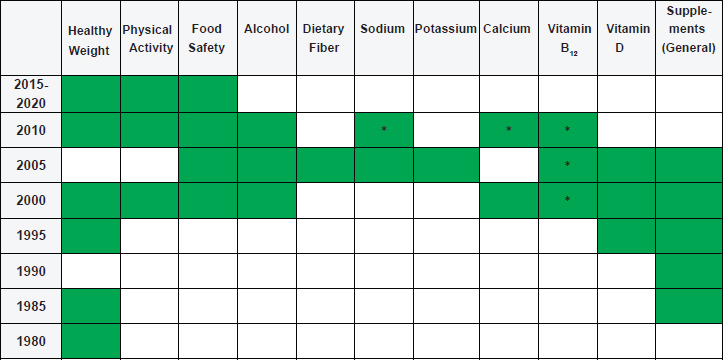

With respect to the future 2020-2025 DGA, Stoody stated that while the DGA have traditionally included recommendations for Americans aged 2 years and older, there has been a growing demand to expand the DGA to cover the population aged 0-24 months. Indeed, she noted, the Agricultural Act of 2014 mandated that the 2020-2025 DGA include dietary guidance for this youngest population, as well as women who are pregnant. For Stoody, this expansion of the DGA raises the question of whether other stages of life warrant more comprehensive guidance, and whether older adults are one of those stages. The current and previous guidelines do apply to older adults generally, she acknowledged, and since 1980, the guidelines have included specific guidance for older individuals (see Figure 5-5). But again, she asked, “Should there be more? Should there be some sort of comprehensive guidance?” In her opinion, this is a conversation that should be taking place.

With respect to future research, Stoody reiterated that the current edition of the DGA is focused on dietary patterns, informed by an evidence base of those patterns in relation to various health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, body weight, type 2 diabetes, certain types of cancer, bone health, depression, and dementia/cognitive impairment/Alzheimer’s disease. In general, however, she believes more evidence is needed across the lifespan. She observed that most of the studies on dietary patterns in the evidence base for the 2015-2020 DGA included subjects who were aged 50 and older (mean age) at baseline and who were followed for approximately 10 years. There is still a gap, she asserted, in understanding how dietary patterns across the entire lifespan contribute to healthy aging. Additionally, she suggested, improved methods are needed for assessing dietary patterns more comprehensively, precisely, and with standardization so that investigators can better define habitual food intake in populations. She noted that some of this work is under way. She also called for stronger methodological

___________________

4 See https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/choosing-healthy-meals-you-get-older (accessed January 18, 2017).

NOTES: The recommendations of the DGA apply generally to older individuals, but there are cases in which specific statements have focused on this population.

* Indicates that these topics are covered for adults aged 50/51 and older.

SOURCE: Presented by E. Stoody, September 14, 2016.

designs—for example, longer duration of follow-up, assessment of dietary intake at multiple time points over the course of a study, and cohort studies that start earlier in life and that capture dietary patterns contributing to health outcomes later in life.

DISCUSSION WITH THE AUDIENCE

In the discussion following Stoody’s presentation, her observation that the gap between recommended and actual intakes was smallest for children elicited a comment from Wendy Johnson-Askew about the difference between this finding and that of Gerber’s Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS) regarding fruit and vegetable intake in infants and toddlers—namely, that this intake is low, particularly for vegetables. In contrast to results presented by Stoody, she observed, FITS data have shown that most young children are not consuming a discrete vegetable serving on any day. In fact, she noted, it was these results from the 2008 FITS study that influenced changes to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food package. Now, Gerber is struggling to find “stealth” ways to provide more vegetables to babies and toddlers. Johnson-Askew asked whether there were methodological differences between FITS

and the studies that yielded the results Stoody had shared and what data sources informed Stoody’s analysis. Stoody responded that the NHANES data on fruit and vegetable intake used to inform the analysis she had shared included mixed dishes (for vegetables) and 100 percent fruit juice (for fruits). Johnson-Askew added that in fact, with infants’ high saturated fat and sodium intakes, their diets (based on FITS data) actually mimic those of adults. She referred to a recent U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study, published in Pediatrics, that produced results very similar to those of FITS. She noted that the CDC study was longitudinal, and showed that eating patterns established in early childhood lasted through the age of 6. She said that, based on what has been observed with NHANES adult data, she suspects these same early eating patterns track all the way through adulthood.

Johnson-Askew’s comments prompted an audience member to comment on vegetable intake as being problematic across the lifespan. In this audience member’s opinion, people do not like the taste of vegetables (e.g., they detect the bitterness or do not like the smell of broccoli when it is cooked). It is not enough, she said, to tell people to eat their vegetables. The challenge, in her opinion, is to incorporate vegetables into dishes in a way that creates flavor profiles people are willing to embrace. Stoody replied that another analysis conducted for the 2015-2020 DGA revealed that the top source of calories was mixed dishes. She observed that incorporating vegetables into these mixed dishes already being consumed may be a strategy for increasing vegetable consumption.

Johanna Dwyer commented on the fact that most people over age 75 or 80 have one or two chronic conditions and that the majority of these people take dietary supplements. She suspects that about half of these older adults also take multivitamins. She observed that some of the assumptions underlying dietary guidance for very old adults appear to be very different from those for younger adults and wondered whether it might be time to develop DGA for adults aged 75 and older. Stoody agreed that it is worth talking about whether any stages of life warrant more comprehensive coverage for which the evidence base exists. She reiterated that older adults might be one of those stages.

Finally, regarding the gaps between recommended and actual intake levels, not just for fruits and vegetables but for all food groups, there was some discussion around the reality that many consumers do not understand some basic concepts in nutrition. Thus while, in one audience member’s opinion, ChooseMyPlate provides a great visual, a gap remains in consumers’ understanding of what that visual actually means. Many consumers do not understand the concept of cup-equivalent, or whole grain cup-equivalent, for example. Stoody agreed and added that the messages that need to be communicated depend on the age group of the audience. She

noted that the National Institute on Aging, for example, communicates about cup-equivalents in a way that is appropriate for older adults. Adding to the confusion, she observed, is that the population has to contend with different messages being communicated from different sources about what constitutes a healthy diet. She encouraged a more collective voice across the nutrition community and communication through a more collaborative lens.

SUPPORTING HEALTHY AGING ACROSS THE LIFESPAN: THE ROLE OF THE FOOD INDUSTRY5

What Constitutes the Food Industry?

In the first of two presentations on the role of the food industry in promoting healthy aging, Morck elaborated on the industry’s complexity. He began by asking, “What constitutes the food industry?” He emphasized the expansiveness of the industry and described its many components, each of which is focused on its own categorical products.

First, Morck explained, are the commodity producers (i.e., producers of raw components), including a “farm fresh” organic component that Morck noted is becoming very popular. Next are the processed/packaged foods, including different types of meal components (e.g., frozen peas, breakfast cereal, pasta), as well as sauces, spreads, dressings, and condiments. These also include prepared dairy products (e.g., yogurt, cheese). Also within this component of the food industry are ingredient suppliers. They are the ones, Morck said, that are capitalizing on bioactives and finding new opportunities to enrich foods in ways, for example, that may influence the microbiome. Another component is the composite meal producers and suppliers. Composite meals include multicomponent entrees, pizzas, and handheld and other “simpler” meals. Yet another component is snacks and desserts, which include salty snacks, confections, and baked and frozen desserts (e.g., ice cream). The beverage component of the food industry includes soft drinks, water, tea, coffee, juices, alcoholic beverages, sports drinks, energy drinks, and fortified beverages. Other food industry components include the makers of specially formulated nutritional products (e.g., infant formula), foods with limited or omitted nutrients or components (e.g., gluten-free products), dietary supplements, and medical foods (i.e., foods for patients with distinctive nutrient requirements that cannot be met by altering the diet alone).

Yet another entirely different dimension of the food industry and food intake, Morck continued, is out-of-home food consumption, including

___________________

5 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Morck.

quick-serve restaurants, sit-down restaurants, and take-away. Relative to other components, this is a component of the food industry over which consumers have much less control in terms of menu choices, he observed. While this situation is beginning to change, he suggested, with some disclosures about calories and some discussion around sodium levels, this area of food intake remains, in his opinion, one that is particularly difficult to manage. The restaurant industry is a $783 billion industry, he noted, accounting for close to 50 percent of food dollars being spent, compared with 25 percent in 1955.

Finally, Morck explained, also out-of-home is the food service component of the food industry. This component includes hospitals; schools; prisons; cafeterias; workplace food services; vending services; and government program suppliers, including school lunch programs, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), WIC, and the military.

Given this expansiveness, Morck suggested, when the question is raised of what the food industry contributes to healthy aging, the question really is what consumers are choosing from this panoply of options to meet their own needs. That said, he asserted, over the past 5-10 years, the food industry has in fact made significant progress toward supporting healthy eating—for example, by reducing sugar, fat, and calories and eliminating trans fat from the food supply. He described how the production and promotion of healthier foods is one of several public commitments endorsed by food company members of the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA), and one for which they are held publicly accountable. GMA is one of the major trade associations of the food industry, he explained.

Drivers That Impact the Food Industry, Support the Food Industry Requires, and What the Food Industry Can Do to Support Healthy Aging

Eliciting the support of the food industry in healthy aging, Morck continued, requires understanding the drivers that impact the industry. First, he emphasized, the food industry sells only products that people buy. It is driven by consumer purchases, with repeat sales based on consumer satisfaction being required for success. Morck referred to the Campbell Soup Company’s initial introduction of reduced-sodium soups as an example of a product change that consumers did not like, forcing the company to dial back its aggressive sodium reduction targets. Second, he observed that people typically do not eat just to fulfill a physiological requirement. Rather, they eat for social, emotional, and other reasons as well, with different people turning to different foods for these purposes. Cost, variety, ethnicity, and availability also drive the diversity of product offerings. Third, Morck said, the industry is governed by regulatory guidelines on marketing, communications, nutrition labeling, and claims. As an example,

he mentioned guidelines for marketing and communicating to children in particular. Finally, he explained, the industry is driven by its overarching commitment to food safety and quality and is constantly striving to improve manufacturing efficiency to keep costs down (i.e., the greater the efficiency, the lower the cost). He added that the food industry is also publicly embracing an increased commitment to incorporating sustainable practices across the supply chain.

According to Morck, the food industry’s provision of nutritional support for healthy aging requires, first, compelling research outcomes with practical applications. He explained that the industry is happy to develop products consistent with the research if it can then communicate to consumers the outcomes of that research and what they can expect from consuming those products. He also called for new tools for identifying and targeting susceptible individuals for personalized recommendations to promote “their” healthy aging, with respect, for example, to their health/disease state, microbiota, or genetic predisposition. He called as well for a cooperative and collaborative regulatory agency to approve validated claims for products when appropriate data are provided, endorsement of evidence-based nutrition concepts by physicians and regulators when these concepts are shown to be cost-effective and therapeutic for patients, and the effective use of social media and technology to bring positive messages about health improvement to consumers.

Currently, Morck continued, health claims approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) represent one means of informing consumers how consumption of certain levels of foods that contribute certain amounts of nutrients may help prevent and reduce the risk of future chronic disease. There are about 18 of these health claims, he noted. Qualified health claims are what he described as more “aggressive” because the strength of the evidence required is not as conclusive as that required for unqualified claims, with this uncertainty having to be disclosed along with potential benefit. According to Morck, the complexity of the language required for qualified health claims is so “obtuse,” and not “consumer-friendly,” that companies are reluctant to use it on their packaging.

Health claims aside, Morck reiterated that the food industry has in fact made significant progress toward supporting healthy eating by reducing sugar, fat, and calories and eliminating trans fat from the food supply. Additionally, the industry has added dietary fiber, mainly through whole grains in flour and soluble fiber in drinks; increased protein, Omega-3 fatty acids, probiotics, iron, and antioxidant vitamins; developed early-stage formulations to hydrolyze proteins and reduce the allergic potential for infants allergic to cow’s milk; and provided medical foods for patients unable to consume normal foods.

Almost all of the large food industry companies are partners in the

Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, according to Morck. This is not “just a food program,” he stressed. The foundation works with communities, including educators and coaches, toward the goal of removing 1.5 trillion calories from the food supply. At last calculation, Morck reported, 6.4 trillion calories had been removed.

In summary, Morck said, the food industry can promote and support research that establishes links between nutrition and healthy aging at all stages of life. He remarked that, although it is becoming more difficult for industry to partner with academia because of perceptions of industry-funded research, industry does fund academic research. He stressed that testing hypotheses through appropriately designed, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials is just as important for industry as it is for the scientific community. Additionally, he noted, the food industry can develop and market products consistent with nutritional recommendations. Doing so is challenging for industry, he observed, because recommendations such as the DGA revolve around dietary patterns, not necessarily individual products, and consumers must make their own choices from among this panoply of products. He added that the food industry can and does collaborate with government agencies on effective ways to communicate the value of products. Finally, he said, the food industry will continue to partner with industry, scientific, academic, and governmental organizations to inform and educate the public and the medical community about nutrition’s vital role in promoting healthy aging.

NUTRIENT GAPS ACROSS THE LIFESPAN AND THE ROLE OF SUPPLEMENTATION IN A HEALTHY DIET6

Echoing Morck’s message, MacKay began his presentation by emphasizing that “industry is one small piece of this puzzle.” Additionally, he stated that, while he recognizes the need to get people to eat more whole grains and vegetables, he also recognizes the dramatic deficiencies in the American diet and practitioners’ need for additional tools to help reach nutritional targets. Such targets exist for a reason, he argued. The fact that certain amounts of folic acid or iodine, for example, are important at certain stages of life cannot be ignored, he said. In his opinion, if someone is not getting these nutrients from diet alone, responsible supplementation has a role. He underscored that he works for the dietary supplement industry and represents both the manufacturers of finished products and the ingredient suppliers.

MacKay described several age trends in the 11 shortfall nutrients identified in the 2015-2020 DGA, 10 of which apply across the entire U.S.

___________________

6 This section summarizes information presented by Mr. MacKay.

population aged 2 years and older (vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin C, folate, choline, calcium, magnesium, fiber, and potassium) and 1 of which applies specifically to premenopausal females (iron). Within these 11 nutrients are 5 of public health concern, he said, nutrients for which underconsumption has been linked to adverse health outcomes: calcium, vitamin D, fiber, potassium, and iron. In adults aged 71 and older, these same shortfalls exist, and in dramatic numbers, MacKay observed. According to the 2015 report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC), 71 percent of men and 81 percent of women have calcium intakes below the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR); 93 percent of men and 97 percent of women have vitamin D levels below the EAR; 96 percent of men and 87 percent of women have fiber levels below the Adequate Intake (AI); and 97 percent of both men and women have potassium levels below the AI.

MacKay reiterated that the consequences of these insufficiencies can be significant. So if efforts to get people to eat better are not working or they are unable to eat vegetables, for example, because they have no teeth, he said, “you need to come up with a solution.” He stressed the importance of practitioners understanding their patients’ points of reference. If the DASH or Mediterranean diet, for example, is far removed from a patient’s point of reference, he said, it is essential to help that person meet those targeted nutrient intakes.

MacKay noted that the numbers in the 2015 DGAC report regarding shortfall nutrients are based on food intake. Biomarker data in the CDC’s Second Nutrition Report show similar shortfalls in the U.S. population, he observed, with the prevalence of nutrient deficiencies not changing much between 1999 and 2006.

Acknowledging the controversy around the impact of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, MacKay remarked that the intake of these nutrients among the U.S. population is on par with that of the populations of countries at the lowest levels (i.e., less than or equal to 4 percent of total fatty acids are EPA + DHA) (Stark et al., 2016). Whether one obtains these nutrients by eating anchovies or sardines, as MacKay said he does, or by taking supplements, he argued that there are reasons to consume the levels recommended by the American Heart Association and others.

MacKay remarked that many experts have expressed discomfort with supplements because of concern that people will take them instead of eating well. He noted, however, that based on work by Bailey and colleagues (2013a,b), the top three reasons people take supplements are to improve health, to maintain health, and to supplement the diet. He interprets these results to mean that people who take supplements are not taking them because they do not like vegetables, for example, or because they think that if they take the supplement, they will not have to eat well. Rather, he said, typical supplement users tend to visit their doctor, not smoke, and eat a

healthy diet. The real challenge of the industry, in his opinion, is getting the supplements into the hands of the people who need them most.

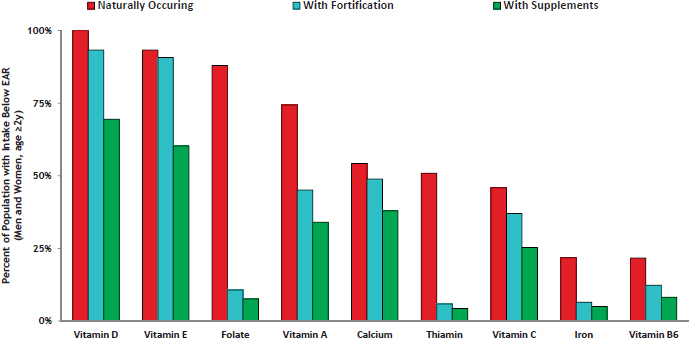

Evidence on the Population-Level Effects of Dietary Supplements

MacKay went on to describe results, based on NHANES 2003-2006 data, showing that when intakes of dietary supplements were accounted for in addition to food intakes, a smaller percentage of the population fell below the EAR for a number of nutrients (Fulgoni et al., 2011). Fulgoni and colleagues (2011), he explained, estimated nutrient intakes from three different sources: foods with naturally occurring nutrients; all foods, including both those with naturally occurring nutrients and those enriched or fortified; and all foods plus supplements. He showed results for eight of the nutrients examined: vitamin D, vitamin E, folate, vitamin A, calcium, thiamin, vitamin C, and iron (see Figure 5-6). When only foods with naturally occurring nutrients (i.e., excluding fortified foods) were taken into account, the percentages falling below the EAR for these eight nutrients ranged from around 25 percent (iron) to close to 100 percent (vitamin D).

SOURCES: Presented by D. MacKay, September 14, 2016. Adapted with permission of the Journal of Nutrition, American Society for Nutrition, from Fulgoni et al., 2011.

When all foods were taken into account, these percentages decreased (i.e., greater percentages of the population met the EARs). And when all foods plus dietary supplements were taken into account, these percentages decreased even further. MacKay reported that the same set of data show that a slightly greater but still very small percentage of supplement users than nonusers were above the Tolerable Upper Intake Level for some nutrients (Bailey et al., 2012).

Women Who Are Pregnant

Women who are pregnant are a highly sensitive subpopulation, MacKay continued, for which three key nutrients are especially important: iron, folic acid, and iodine. There are well-documented consequences of shortfalls of each of these three nutrients, he noted. He explained, however, that the challenges in this regard are tricky because 50 percent of pregnancies are unplanned.

MacKay explained that iron is considered a nutrient of public health concern for women capable of becoming pregnant, with consequences for both the pregnancy and offspring. The folic acid recommendation (i.e., that women capable of becoming pregnant should consume 400 mcg of synthetic folic acid daily from fortified foods and/or supplements) is intended not to meet targeted levels but to provide protection against neural tube defects and is specific to supplemental folic acid. MacKay noted that with respect to iodine, a cluster of concerned physicians, including members of the American Thyroid Association, the Endocrine Society, the Teratology Society, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, are seeing a subchronic insufficiency of this nutrient in the United States. All of these associations have policy statements recommending that all pregnant U.S. women take a daily prenatal vitamin that contains 150 mcg of iodine in the form of potassium iodide.

Older Adults

In addition to the shortfall nutrients listed above, MacKay identified protein and vitamin B12 as two additional nutrients to consider among older adults. While protein is not a shortfall nutrient, he noted that emerging evidence is beginning to demonstrate benefits of protein intakes above the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) levels, especially for older adults and for hospitalized individuals recovering from injury. (See also the summaries of the presentations of Mary Ann Johnson in Chapter 2 and Roger Fielding in Chapter 4 with respect to the controversy concerning protein intake in older adults.) Nor is vitamin B12 a shortfall nutrient, he added, but for older adults with atrophic gastritis whose ability to absorb vitamin

B12 is compromised, the 2010 DGA included a recommendation either to include foods fortified with crystalline B12 or to take a dietary supplement. In MacKay’s opinion, even if a person is eating healthfully, supplementation may still be important.

To demonstrate the role of supplements in supporting nutrient adequacy among older adults (age 71 and above), MacKay highlighted calcium and vitamin D. He noted that, based on NHANES 2003-2006 data, calcium intake from foods and beverages did not meet the EAR for older persons, with 71 percent of males and 81 percent of females in this age group having intakes below the EAR. For these analyses, he added, calcium from dietary supplements was also considered. When total intake of foods plus beverages plus dietary supplements containing calcium was considered, the proportion of older adults (age 71 and above) below the EAR improved to 55 percent for men and 49 percent for women (DGAC, 2015). The difference was even more dramatic for vitamin D, MacKay said, with almost none of this older population meeting the EAR with food alone, but about half (both men and women) meeting it with supplements.

The Supplement Industry’s Role in Promoting Healthy Aging

In summary, MacKay said, the “lens” of the dietary supplement industry is that, based on the science, significant proportions of the population have inadequate nutrient intakes, and nutrient supplementation is a safe, practical means of improving those intakes. Thus, he explained, the role of the industry in supporting healthy aging is to promote responsible use of dietary supplements in combination with a healthy diet as a way to ensure nutrient adequacy. He noted that the industry takes on this role at both the population and the individual levels.

Industry efforts to promote healthy aging at the population level, MacKay elaborated, include investing in a series of health care cost analyses (i.e., conducting economic analyses to estimate the health care cost savings associated with achieving targeted nutrient intakes for certain disease conditions, such as adequate calcium and vitamin D intakes for bone health); advocating for a multivitamin to be included as a choice in food assistance programs (e.g., SNAP, WIC), given that those in need of food assistance tend to have the greatest nutrient gaps; setting an industry guideline for iodine level in prenatal multivitamins (MacKay mentioned that CRN was currently running a study to evaluate the impact of this guideline); assembling dossiers for health claims or qualified health claims for magnesium (i.e., with respect to blood pressure) and omega-3 fatty acids; and supporting global humanitarian nutrition initiatives, such as Vitamin Angels and Sight and Life.

MacKay explained that industry efforts to promote healthy aging at the individual level (i.e., to meet individual recommendations) revolve around

the products. He stated that dietary supplements are science-based products formulated for specific populations (i.e., by life stage and sex). A multivitamin for a woman who is pregnant, for example, is based on one set of nutrient needs, while a multivitamin for a woman who is menstruating is based on another. Additionally, MacKay continued, the industry makes products to complement certain types of diets, such as vegan (e.g., vegan sources of long-chain fatty acids), vegetarian, and lactose-free diets. He noted that the industry also provides products in alternative and creative delivery forms (e.g., powder, liquid, tablet, capsule, gel cap, gummy).

Finally, MacKay addressed managing consumer expectations. “You cannot ignore the push toward sensationalism with aging,” he said, as he showed a slide with an image of a television set, with two television personalities in the foreground and on the set in the background the words “The Miracle Pill to Stop Aging.” Responsible messaging, he asserted, emphasizes that there is no miracle pill and that people should talk to their physicians. As an example, he mentioned CRN’s supplement advertising program, a 10-year program conducted through the Better Business Bureau but with CRN-hired attorneys who challenge supplement manufacturers to either provide substantiation or change the message if substantiation is inadequate.

DISCUSSION WITH THE AUDIENCE

Following MacKay’s talk, he and the other speakers in the session participated in an open discussion with the audience. Johanna Dwyer opened the discussion by mentioning the fact sheets on dietary supplements issued by ODS. She commented on problems with the dissolution and disintegration of some supplements and remarked that some of these products may not have the intended effects because they are not absorbed. MacKay responded that this is one of the reasons biomarkers of intake and status are so important in expensive, large studies and need to be collected at baseline and over the course of the study (so it is clear, in the study, whether the product had an effect). Additionally, he noted, monographs of the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) include specifications for dissolution. He explained that USP conducts testing to ensure that these products are in compliance with its standards, and while those standards are voluntary, they are mandatory if a company carries the USP seal. To meet USP standards, he continued, a product needs to dissolve based on how dissolution for that product is defined. While this is “not a perfect situation,” he said, the industry is aware of the challenge. He stated that when marketing, responsible companies include only claims with evidence (e.g., “twice as absorbable”).

An audience member asked what types of research the food industry has been effective in supporting and areas in which, looking ahead, the

industry could focus in this regard. Morck replied that what is of great interest to the industry is research results that can be used to support patents or proprietary use of ingredients or processes so that a unique product can be differentiated from its market competitors. Historically, he noted, much of that research has been on bioactive components of a healthy diet (e.g., bioactives such as bioflavonoids or curcumin that are suspected of being associated with a healthy diet). The challenge, he said, is that many research questions are related to disease outcomes (e.g., whether a product affects blood pressure or gastrointestinal conditions or symptoms). He added that a product may in fact improve certain health outcomes, but if these outcomes are associated with improving disease symptoms, the FDA considers the product a drug, not a “food.” He explained that there may be areas in which a product consisting of food-derived ingredients may have therapeutic value, and sophisticated tests and tools exist to show that the product may be effective at the physiological or cellular level, but the regulatory paradigm is interpreted “narrowly.” Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, for example, are viewed as having the same nutritional requirements as do other individuals in the population. Thus in the current paradigm, Morck said, there is no justification for a medical food for individuals with this condition. He argued that the use of population-based, epidemiological models to set nutrient requirements appropriate for the “general healthy population” fails to consider that patients with disease fall outside this definition. Thus, he believes that new definitions of individual variability in needed nutrient levels are desperately needed to advance this field. He added that in the area of research on infant formula, it took 10 years of evidence showing that specialized hydrolyzed protein formula could be beneficial for babies susceptible to cow’s milk allergy before the weight of evidence became compelling enough to obtain a qualified health claim.

MacKay mentioned the Physicians Health Study II again, which showed a reduction in cancer risk associated with multivitamin use, and noted that companies provided multivitamins to 11,000 physicians for 10 years with no expectation regarding outcomes. He described any added effect of a multivitamin in reducing the risk of heart disease, for example, beyond state-of-the-art medical treatment as a “pretty heavy lift,” yet companies provided their products for this study at no cost. In fact, he said, the multivitamins did show benefits. Subsequently, he added, CRN conducted a secondary analysis and showed that the effects differed depending on diet. “So the industry is willing to put the money forward,” he concluded.

A member of the audience commented on the industry’s recognition of the importance of funding research to better understand the population-level effects of components of the diet. For example, General Mills identified whole grains as a focus of research before they became part of the DGA. This research, the audience member noted, has helped build a da-

tabase that can advance understanding of the relationship between whole grains and health and has impacted how General Mills thinks about its grain products, particularly cereals.

Maha Tahiri, Food Forum member, added that consumer research is another area of research to which the food industry contributes. One of the gaps in the DGA, she observed, is that people do not follow the guidelines. There is much to understand about barriers and motivators, she suggested. Food companies do this type of research, she said, that is, research focused not on branded products but on ethnography. As an example, she noted that General Mills has 15 years of data on what motivates people to lose weight, showing that these motivators are very different for different populations. She told of one researcher who asked a low-income mother who was participating in one of these studies to describe a healthy meal. The woman replied, “pot pie.” According to Tahiri, the woman thought that because pot pie has dairy, starch, and vegetables in it, it is healthy. So when the message is to eat more fresh fruits and vegetables, she said, different people interpret that message differently. She believes that through this research, industry can help build a better understanding of what motivates consumers, which in turn can inform efforts to improve the effectiveness of the DGA. “I really see that there is an opportunity for us to share some of our knowledge . . . and what motivates [consumers] and really reaching what we all want, which is for [consumers] to follow the dietary guidelines,” Tahiri said.

Dwyer commented on the popular phrase, “70 is the new 50” and asked the panelists whether, therefore, 90 is the new 70. Reuben responded, “Maybe.” He identified three factors to consider: (1) how well one takes care of oneself, including exercise; (2) genetics; and (3) luck. In his opinion, luck is often discounted with respect to health. He mentioned having many patients in their 90s who are still working. Most of them, he said, are artists.

A member of the audience commented about the need to temper some of the positive findings regarding progress made by the food industry. For example, the audience member noted, a third-party University of North Carolina evaluation found that the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation’s removal of 6.4 trillion calories from the food supply translates to about 90 fewer calories per person per day. As another example, while calories are declining in the restaurant sector because of mandatory menu labeling that will go into effect in 2017, this commenter believes the restaurant industry has made minimal progress in reducing saturated fat or sodium. In response, Morck called for appropriately validated biomarkers of nutritional status that he suggested should be as easy and convenient to use as a blood pressure cuff. He imagined something that would be on one’s phone and could be used to scan a menu in a restaurant to find out exactly

what one was eating. “Without knowledge of what we are eating, he said, “we can’t make knowledgeable choices.”

Finally, a question was raised about the appropriate nutrition for patients who are going through chemotherapy, for example, and what physicians need to do to advocate in this regard in addition to considering the impact of older age and coexisting nutrient deficiencies. The questioner noted that she has watched patients undergo chemotherapy with no nutritional guidance, and that some physicians even tell their patients to stay away from multivitamins. In response, Stoody agreed with others who had urged that everyone has a role in promoting healthy eating and also agreed on the importance of the consumer. Regarding the DGA, she emphasized that the guidelines are about prevention of chronic disease and promotion of healthy eating, but not treatment. In her opinion, the promotion of healthy eating in treatment is a broader conversation that should involve multiple agencies working together.

This page intentionally left blank.