TENSIONS AND CHALLENGES TO ADEQUATELY AND EFFICIENTLY FINANCE HEALTH PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

Edson Correia Araujo, World Bank

Edson Correia Araujo is a senior economist at the World Bank, and led the World Bank health workforce global knowledge program. His presentation focused on the interaction between health professional education (HPE) and labor markets from a global perspective, with examples of trends and challenges from low- and middle-income countries as well as high-income countries.

The Health Labor Market: A Framework for Analysis

Araujo led a recent World Bank publication, The Economics of Health Professional Education and Careers: Insights from a Literature Review (McPake et al., 2015). The aim of the publication was to document what is known about the influence of market forces on the health professional formation process. The report explores the interactions between the markets for health care and for health workers, as well as the health professionals’ education choices in the context of low- and middle-income countries.

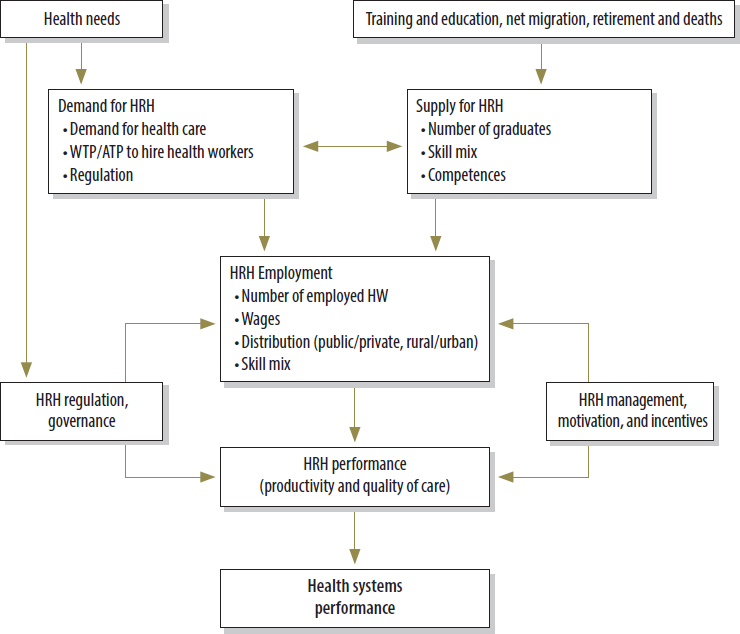

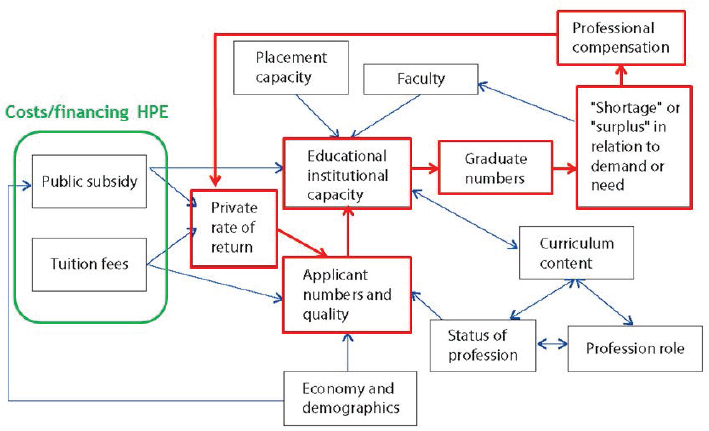

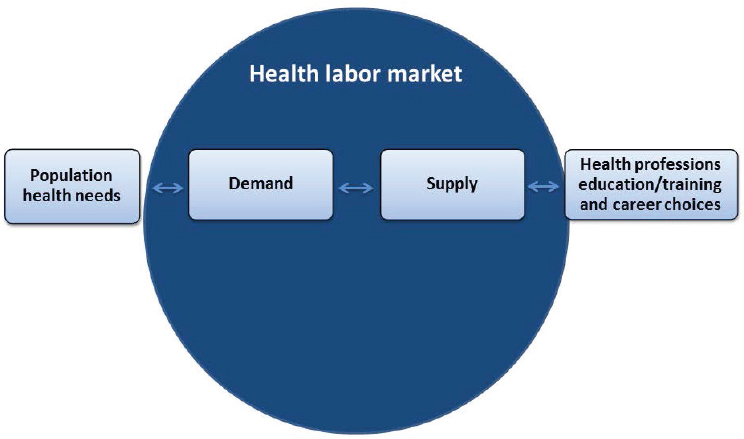

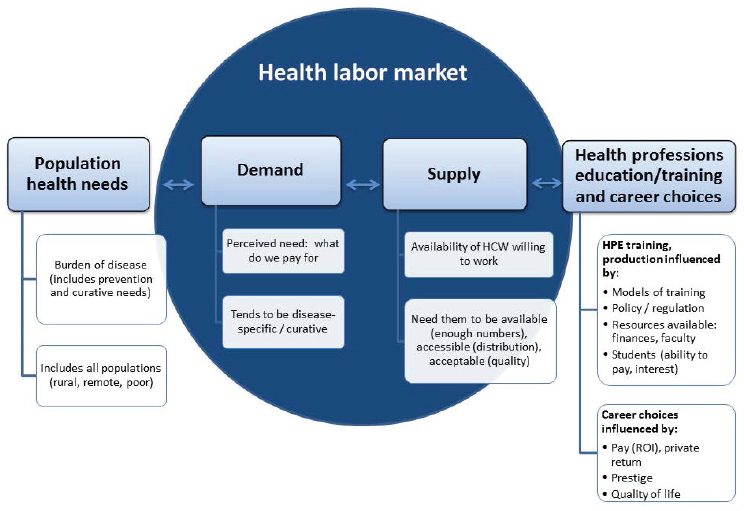

Araujo described the market forces that exist within the health labor market, describing the factors influencing the demand for and the supply of health workers (see Figure 2-1). As shown in Figure 2-1, the demand for health care influences the production and training of health workers—or the supply of health workers. In principle, this demand should be determined by the population’s health care needs. In ideal circumstances, health care needs would be translated into actual demand, and the training institutions would produce the necessary supply of health workers to fulfill the demand. However, this seldom happens owing to the existence of market failures in both health and labor markets. These market failures explain, to a great extent, the persistent challenges most countries face in producing, deploying, and retaining an adequate and well-performing health workforce. The health worker shortage (described in Chapter 1) is further exacerbated by the imbalances in the distribution across and within countries, he said. In most countries, health workers tend to be concentrated in urban and wealthier areas, leaving rural and poorer areas with severe shortages. In Togo, for example, 17 percent of doctors serve 80 percent of the population living outside of the country’s capital (World Bank, 2011). This pattern is found in low-, middle-, and high-income countries across the globe.

In addition to its importance to health service delivery, the health workforce represents a large portion of the labor force in most countries, and this number is growing despite economic recessions. In the United States, for example, the health workforce share of total employment is 10.71 per-

NOTE: ATP = ability to pay; HRH = human resources for health; HW = health worker; WTP = willingness to pay.

SOURCES: Presented by Araujo, October 6, 2016 (McPake et al., 2013, adapted from Soucat et al., 2013).

cent, with a cumulative growth of 11.2 percent during the latest recession (Turner et al., 2013). Among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, the health and social sectors share of total employment is just over 10 percent on average, with large cross-country variation—the highest share of 15 percent in the Nordic countries and the Netherlands, and the lowest share of about 3 percent in Mexico and Turkey (OECD, 2016). The increase of health sector jobs raises concerns related to sustainability of health systems and the effect on the economy as a whole. Globally, health workers salaries account, on average, for 34 percent of countries’ total health expenditures—and 57 percent in the United States (Hernandez-Peña et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2013). These trends emphasize

the importance of producing a health workforce in adequate numbers, with the appropriate skills and competencies to maximize job creation and to improve population health outcomes.

The Interaction Between Labor and Education Markets

Araujo cited the Lancet Commission report (Frenk et al., 2010) that states that the challenge lies in transforming the needs, which are generated by the population, into demand. Such a transformation of needs into demand does not always occur. Often, this is attributed to an information gap between the patients and the providers. Health economists see this lack of transformation as a market failure, said Araujo, and have been working for years to address it.

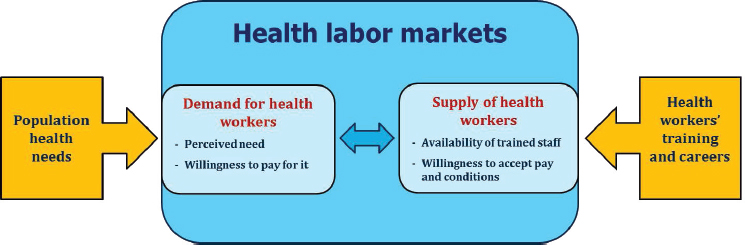

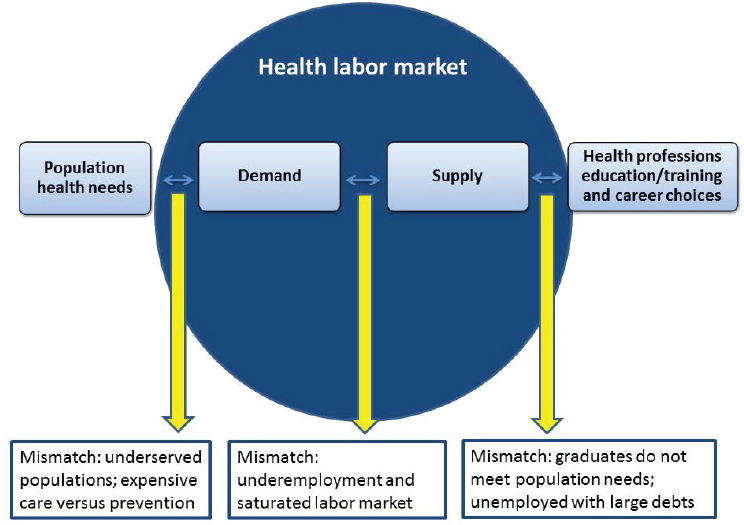

Araujo then presented a model (see Figure 2-2) showing the interaction between education and labor markets within the health sector. He began to describe the conflicts, tensions, and imbalances between health care needs and demand, health professional training and supply, and demand and supply.

NOTE: This is an adaptation of an original work by the World Bank. Responsibility for the views and opinions expressed in the adaptation rests solely with the author of the adaptation and are not endorsed by any member institution of the World Bank Group.

SOURCES: Presented by Araujo, October 6, 2016 (adapted from McPake et al., 2015).

An Overview of Need, Demand, Supply, and Training of Health Professionals

According to the model presented, the market for HPE is skewed by the same market failures inherent to health care markets (McPake et al., 2015; Preker et al., 2013). The main market failure is, as mentioned above, information gaps. Patients, or consumers, know less about their own health status and the appropriate treatment than the health care providers. This information asymmetry results in providers supplying more health care than necessary or demanded (supplier-induced demand). Additionally, the demand for health workers and for health services are influenced by perceived need, which is different from actual need. This can result in a gap between willingness to pay and informed willingness to pay; in other words, patients may be unwilling to pay for services that they need, or may be willing to pay for services that are not necessary or are not cost-effective. Another issue that results from information gaps is the problem of wage rates not reflecting the value of the health professional as measured by social return and effect on public health.

Another market failure that affects HPE, as identified by Araujo, is the challenge of transforming health care needs into actual demand. The distribution of ability to pay for services is often inversely related to needs; people with the greatest need, often the poor or those in rural areas, tend to have weaker demand to buy the services they need because of barriers to access and inability to pay. In addition, said Araujo, the governments often have limited fiscal capacity to compensate for health care services or weak political will to compensate these individuals or to invest in public services to help fulfill their health needs.

Market failures cause suboptimal allocation of resources in the health care and HPE markets. First, there is a global shortage of health workers, and the shortage is growing. A World Bank report estimated that the global demand for health workers will rise to nearly 80 million by 2030, which is about double the current stock (Liua et al., 2016). This report also projects a global demand shortage of 15 million health workers by 2030, maintaining the current patterns of demand and production of health workers (Liua et al., 2016). When taking into account aging populations, rise of chronic diseases, and other changes in health care, this shortage will likely increase. The second imbalance Araujo identified is skill bias, or overspecialization. Globally, there is a tendency for health workers to seek specialization, and as a result, there is a persistent supply of health workers for higher lifetime-earning specialties. This also results in a persistent excess of demand for lower lifetime-earning positions, often the public health workforce and generalist practitioners (McPake et al., 2015). Third, there is an acute maldistribution of health workers. The majority of health workers worldwide

tend to be concentrated in affluent urban areas rather than in rural and poorer areas (Preker et al., 2013). Many health workers often migrate from low- and middle-income countries to high-income countries to seek greater financial and working opportunities.

The supply of health workers is influenced by numerous factors including workers’ training capacity, the real or perceived need for health workers, and the availability of trained staff willing to practice. From the labor market perspective, wage rate is a key variable influencing the supply. Economists observe the influence of wage rate based on the private rate of returns to education; in other words, the individual returns that one receives for investing time and resources into training (or the private return). High private rate of returns is a market signal to prospective students, affecting their career choice, and therefore the supply of health workers. In addition, as previously discussed, patient demand and insurance reimbursement often fail to flow resources according to public health needs, often resulting in higher payments for highly specialized services. This means that these specialized services have a higher rate of return to health professionals providing them. Private return is different from the public and social returns for that individual’s training, which Araujo believes should guide HPE financing decisions. If the market is left untouched, the private returns will be more influential on individual decision making and, likely, the current skill imbalance will remain.

Another important trend affecting health labor markets is the increased use of technology in health care. Technology incorporation results in a higher rate of return to education for higher skilled workers, as these services are more expensive and demanded by patients. This results in changes to the elasticity of demand for high-skilled workers relative to low-skilled workers, and makes it difficult to substitute between higher- and lower-skilled workers (Schumacher, 2002).

Population Health Needs and Demand for Health Workers

Araujo stated that owing to the market failures discussed, unregulated health labor markets are unlikely to move to an equilibrium, or a situation where needs, demands, and supply are matched. If the health labor market is left alone, the outcomes will likely negatively affect poor, remote, and disenfranchised populations. The demand for health workers is influenced by

- market signals, sent through rates of returns to education, which affect individuals’ training and career choices (careers with higher compensation are more likely to attract individuals; whereas, careers with low compensation drive individuals away from those positions); and

- patient demand and insurance reimbursement failing to reflect the social and public value of HPE.

Araujo said that these market forces influence the allocation of labor inputs and often result in

- health care jobs concentrated in urban or hospital settings, focusing on acute care to treat ill patients;

- shortage of primary health care positions and shortage of health workers in rural and poor areas; and

- access to care based on a patient’s ability to pay for care.

To demonstrate the links between compensation and individual career choice, Araujo presented some evidence to workshop participants. First, he presented a table from Roth (2011) that showed physician specialties, the individual rate of return (IRR), the years needed to graduate, and the median annual earnings. Noninvasive radiologists have a 38.9 percent IRR with median annual earnings of $304,586.10. On the other end of the spectrum, family practice doctors have a 16.8 percent IRR with median annual earnings of $132,479.28. General pediatricians have a 13.9 percent IRR with median annual earnings of $138,240.00 (Roth, 2011). Another study found that cardiologists made roughly double the amount of primary care physicians reiterating the fact that “over their lifetimes, primary care physicians earn lower incomes—and accumulate considerably less wealth—than their specialist counterparts” (Vaughn et al., 2010). Araujo also presented evidence showing that in countries of the OECD, the growth rates of salaries for general practitioners are historically lower than for specialty positions.

Araujo explained that in Brazil, the growth of private health insurance in the late 2000s boosted the demand for health workers in the country. Given the government’s inability to expand the production of health workers quickly, there was a large expansion of private medical and nursing schools in the country (Scheffer and Dal Poz, 2015). In China, the challenge relates to low compensation to health workers in a fast-growing economy. Health care occupations have lower salaries than other occupations with similar education requirements (Qin et al., 2013). There are strong incentives for health workers to produce more services (supplier-induced demand) and see more patients in order to supplement their salaries. This creates tensions between the health care professionals and the patients, in some cases resulting in violent incidents. Araujo said that as a result, health professions became less attractive to prospective students, and those who chose a health professional career often choose not to enter clinical practice,

instead choosing to enter the biotechnology or pharmaceutical industries (which are fast-growing industries in modern China).

Referencing the Lancet Commission report (Frenk et al., 2010), Araujo reminded workshop participants that only 2 percent of total health care expenditure goes toward health professional education (about $100 billion out of the roughly $5 trillion spent globally). To him, this is a very small investment for a sector that is mostly based on labor. He also pointed out that the spending is not focused where it needs to be in order to meet population health needs, as there are problems with student debt, cost of application, and faculty salaries.

Health Workforce Supply and Health Workers’ Training

The production of health professionals is influenced by the availability of resources and the rate of return to education, as well as models of training, regulation, prestige, and quality of life. However, HPE institutions do not always respond to the demand for training. These aforementioned factors cause many effects on the supply of health workers (Evans et al., 2016):

- inadequate scale and narrow scope of education institutions;

- curricula focused only on marketable skills, owing to certain specialties having higher rates of return than others;

- accreditation and licensing functioning as barriers to entry and failing to promote quality; and

- a weak and homogenous pool of eligible students, that often lacks students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

These effects then result in a health workforce with a skills imbalance (more specialists than primary care professionals), a workforce that is overspecialized (as a result of the technology changes), and a higher cost of training.

Supply of Health Workers and Health Workers’ Training: The Health Workforce Shortage

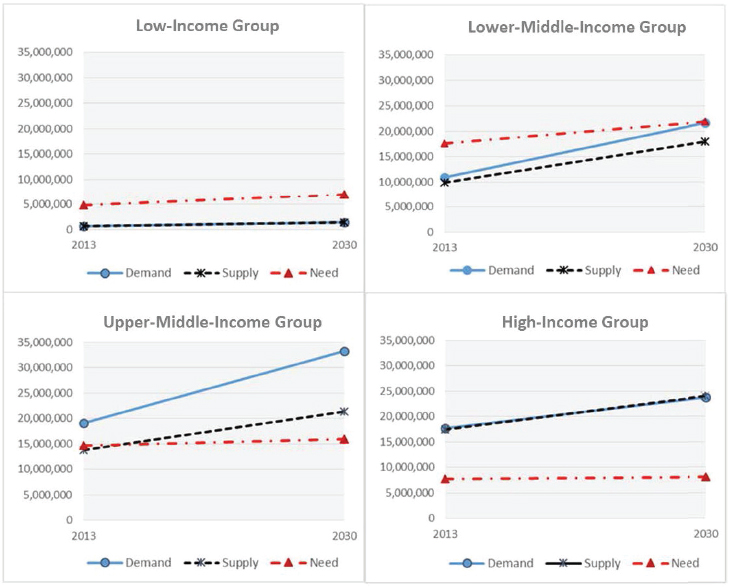

Araujo stated that there is a shortage of health professionals, and the needs and the demands of the growing global population are not being met. In most countries, the demand is much higher than the supply of health workers. This means society is not producing health professionals at the same rate as the population growth and is not keeping up with demands for services. The same is true for all health workers and not just professionals where the supply is not keeping up with the need and the demand. This is

SOURCES: Presented by Araujo, October 6, 2016 (Liua et al., 2016).

a global issue, and is especially acute in low- and middle-income countries, as shown in Figure 2-3.

Looking at public and private education, it appears that the public education sector has not been able to meet the increased demand for health workers. The private education sector is growing, but it is still unable to meet the increasing demand, said Araujo. These issues can also affect quality, given that private HPE institutions are often unregulated in low- and middle-income countries. Araujo noted that these trends are observed in Brazil, India, Indonesia, and many other countries. Quality assurance mechanisms (accreditation of schools and certification of professionals) need to be in place to ensure that the supply of health workers meets quality standards, said Araujo. However, it is also important to avoid entry restrictions into the labor market beyond what is necessary to assure quality; accreditation and certification are sometimes seen as instruments to restrict labor market entry and artificially control supply.

Another issue that Araujo raised is the problem of student debt. HPE, in general, is very expensive. If students have to bear the cost of education, there will be incentives to pursue specializations with higher salaries (and consequently, receive higher rates of return to education). This could result in health care occupations with relatively lower salaries being ignored—and often, these are the positions that have a higher impact on population health care needs. The growing size of student loans results in students more likely to seek jobs with higher salaries in order to pay back their loans.

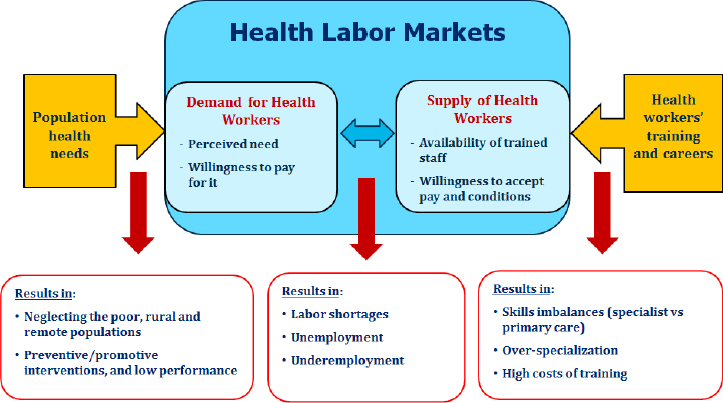

The Health Labor Market Imbalances

Revisiting Figure 2-2, Araujo described the results of health labor market imbalances; specifically, imbalances between population health need and population health demand, between population health demand and health workforce supply, and between health workforce supply and health worker’s training and careers (see Figure 2-4). The demand and supply sides are interlinked, and affected by the market signals coming from the population

NOTE: This is an adaptation of an original work by the World Bank. Responsibility for the views and opinions expressed in the adaptation rests solely with the author of the adaptation and are not endorsed by any member institution of the World Bank Group.

SOURCES: Presented by Araujo, October 6, 2016 (adapted from McPake et al., 2015).

health care needs, from health service delivery and payment systems, and from HPE institutions. The imbalances result in many outcomes identified by Araujo, as noted below and also in Figure 2-4:

- neglect of poor, rural, and remote populations

- balance of the workforce in terms of preventive and promotive interventions, as well as lower performance

- labor shortages

- unemployment and underemployment

- skills imbalances

- over specialization

- high costs of training

He reminded workshop participants that it is important to consider the link between the cost of care and what one pays for HPE. In addition, he noted that the growing cost of higher education is not specific to the health professions but is an issue in many other sectors.

To summarize the various factors that affect the supply and demand of health professionals, Araujo presented Figure 2-5. The figure shows the

NOTE: This is an adaptation of an original work by the World Bank. Responsibility for the views and opinions expressed in the adaptation rests solely with the author of the adaptation and are not endorsed by any member institution of the World Bank Group.

SOURCES: Presented by Araujo, October 6, 2016 (adapted from McPake et al., 2015).

interactions between some of the various supply and demand elements; the arrows demonstrate how these elements interact. The figure highlights the diverse interconnections influencing HPE outcomes and how these are linked to health labor market institutions and dynamics. It also provides a framework to guide how public investments can be channeled to target the outcomes of interest, which is a well-balanced workforce with the appropriate numbers (i.e., supply) and skills.

Costs and Financing of HPE

Araujo then turned to the financing of health professional education. He first noted that examining the cost and financing of health professional education is difficult because the data are not available in many countries (though the United States is in a privileged position in terms of data availability). The result of such limited data is that very few studies exist on the costs and returns of investing in health professional education.

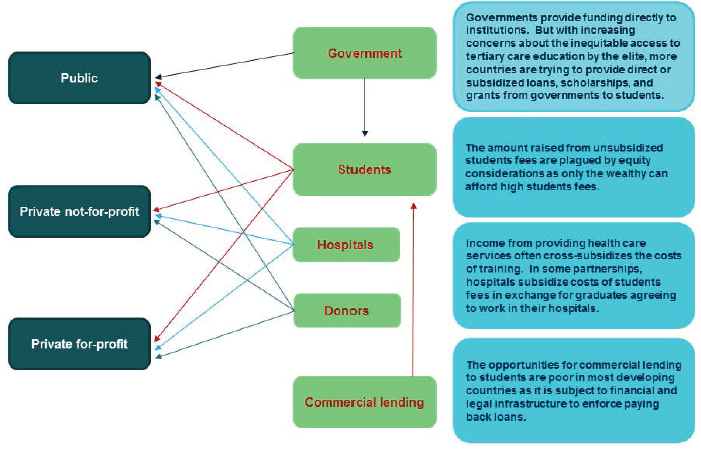

Despite the problem with data availability, it is still possible to see the complexity of the health professional financing system, as shown in Figure 2-6. This illustration shows the sources of financing for medical and nursing schools and teaching hospitals in low- and middle-income coun-

SOURCES: Presented by Araujo October 6 2016 (Preker et al. 2013).

tries. The funding mechanisms are very complex and involve many sources of funding; this includes students, hospitals (both public and private), donors, and commercial lending. In addition, the government contributes to financially supporting the students. There is also a large amount of funding for research, especially in medical schools, which helps to pay for the faculty’s salaries. The complicated financing structure for HPE needs to be considered carefully, especially when discussing where to prioritize investment in HPE.

There is a lack of evidence on costs of HPE, which is partly explained by the complexity of the financing structures. Araujo presented Table 2-1 from a World Bank publication, which shows the expenditure on health training institutions in Ghana (Preker et al., 2013). The table includes the health profession, the years it takes to complete the degree, and the cost of the degree. By looking at the length of time in addition to the cost of the degree, one can see what exactly is invested in order to produce certain health professionals. He emphasized the need of such detailed data in order to measure the returns of investing in HPE.

Health Professional Education for Universal Health Coverage

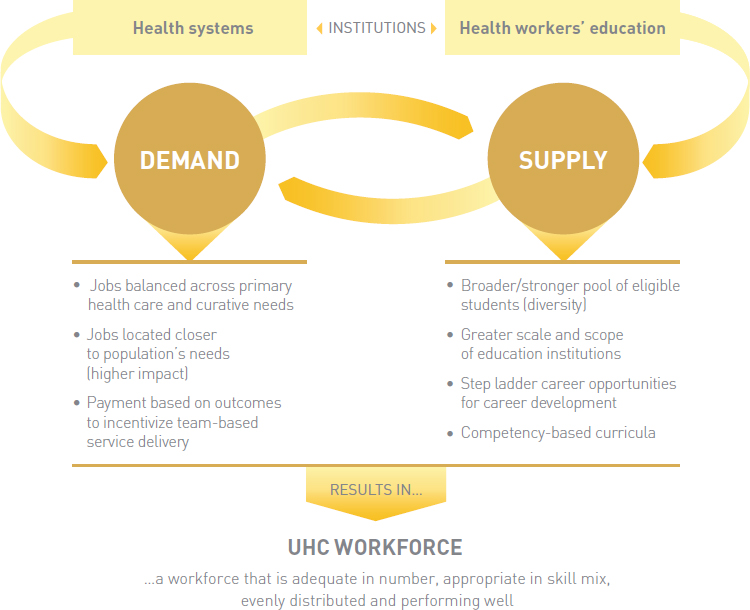

Universal health coverage is the World Bank’s flagship action in the health sector. The World Bank has formally endorsed it, and it is advising countries that seek to achieve universal health coverage. Recently, a World Bank team produced a report on HPE and the challenges for universal health coverage, titled Addressing the Challenges of Health Professional Education: Opportunities to Accelerate Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage (Evans et al., 2016). Araujo challenged participants to look forward to what the health labor market would look like in a situation with universal health coverage, and what changes in the health workforce and in HPE would be required. This desired situation will require transformation in both the demand and the supply side of HPE, said Araujo (see Figure 2-7).

On the demand side, Araujo said health systems need to demand jobs that are balanced across primary health care and curative needs, jobs that are located closer to the population’s needs, and payment systems that are based on outcomes and structured to incentivize team-based service delivery. In other words, said Araujo, to change the composition of the health workforce, the delivery of services must be changed. This would provide clear market signals that ultimately will encourage individuals to invest in professions where there is a higher social and private return on training investments. This would then require that private and public schools adjust their curriculum and structure of training for what individuals are demanding.

TABLE 2-1 Expenditure on Health Training Institutions in Ghana

| Profession | Years | Annual Cost | Total Recurrent Cost ($) | Total Capital Cost | Investment Ratio (percent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors | 6 | 8,975 | 18,084,625 | 236,883 | 1.3 |

| Specialists | 4 | 10,785 | 3,235,500 | 43,000 | 1.3 |

| Dental surgeons | 5 | 7,500 | 1,132,500 | 54,307 | 4.8 |

| Pharmacists | 4 | 3,161 | 2,174,768 | 31,114 | 1.4 |

| Professional nurses* | 3 | 990 | 7,661,610 | 1,126,450 | 14.7 |

| Midwives | 3 | 2,376 | 3,466,584 | 72,450 | 2.1 |

| Laboratory technicians | 3 | 2,600 | 483,600 | 10,000 | 2.1 |

| X-ray technologists | 3 | 2,600 | 530,400 | 10,000 | 1.9 |

| Pharmacy technicians | 2 | 350 | 14,000 | 300 | 2.1 |

| Community health nurses (certificate) | 2 | 323 | 1,093,678 | 239,353 | 21.9 |

| Health assistants | 2 | 386 | 1,387,516 | 117,419 | 8.5 |

| Medical assistants | 3 | 500 | 193,000 | 40,000 | 20.7 |

| Others | 3 | 300 | 588,000 | 5,000 | 0.9 |

| Total | n.a. | n.a. | 40,045,781 | 1,986,276 | 5.0 |

NOTES: n.a. = not applicable. At the time of the study 1 Ghanaian cedi was equivalent to $1. The cost calculation is based on an average cost coming from the Ghana preinvestment study, coupled with the capital investment budget data from the Ministry of Education (National Council on Higher Education) and Ministry of Health.

* Combines the three categories across different costs (diploma, bachelor, and postgraduate).

SOURCES: Presented by Araujo, October 6, 2016 (Preker et al., 2013, adapted from Beciu, 2009).

NOTES: PHC = primary health care; UHC = universal health coverage.

SOURCES: Presented by Araujo, October 6, 2016 (Evans et al., 2016).

On the supply side of HPE, Araujo said there is a need for a more diverse pool of eligible students. In many low- and middle-income countries, many health professional students, especially medical students, come from a very privileged group of the population. He mentioned the case of Brazil, where the government has undertaken some initiatives in order to reserve a certain number of spaces for students from public schools, in order to try to reduce the homogeneity of the health professional student group. He also pointed out that the World Bank report argues for a greater scale and scope of educational institutions (Evans et al., 2016), competency-based curricula, and a stepladder of opportunities for career development.

At the close of his presentation, Araujo summarized how labor and health care markets shape the outcomes of HPE. He revisited the 2010 Vaughn study he noted earlier that discussed the large salary gap between

cardiologists and other health professionals. The study found that only half of the gap in pay can be attributed to working longer hours, spending more time in training, or having more specific and technical skills. Higher rates of return are the result of higher relative pay for these specializations. Araujo then listed a few of his recommendations and viewpoints:

- Economic incentives are critically important in shaping demand for and supply of health professional training (as well as its outcomes).

- Most countries manage economic incentives poorly. The workforce is overspecialized, over medicalized, and hospital centric.

- Countries and governments should prioritize and weigh subsidies in nursing and medical training toward generalist training.

- There should be more investments in training mid- and low-level providers. A more balanced composition of the health workforce will likely lead to a higher social rate of returns.

- Mobilize private international investment for regulating private training (accreditation and certification).

- There should be concentrated efforts to generate more data on health workers’ compensation, costs of training, and career choices.

Discussion

Erin Fraher, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, then opened the floor for questions and discussion. Elizabeth Hoppe, representing the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry, asked Araujo to describe in more detail the discrepancy between need and perceived demand, and specifically if this discrepancy is at all caused by individuals not following recommendations or guidelines for preventive care or frequency of care. John Finnegan, representing the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH), also asked Araujo about the demand side, and if there is any evidence that one can change the agenda for demand to deflect the demand curve to move in a specific direction. He noted that this kind of action would involve policy makers and would assume the ideal direction for the demand curve is known.

In response to these questions, Araujo acknowledged there are individual information gaps that cause discrepancies between need and demand. For example, patients often look for signals, such as a clean health care facility, availability of high-end technology, or a friendly health professional, in order to make their health care decisions. These are perceived quality aspects, in opposition to actual quality. These and other quality signals unrelated to a person’s or population’s health needs influence the demand for care. In addition, many patients may opt not to follow the advice of their health care provider and instead will search online for the best treatments

or medicines. In many cases, these medicines are more expensive than ones prescribed by the health care provider. The drivers of demand, he said, are often not related to the actual needs from the individual side. The demand then drives the cost of services.

An additional complication, said Araujo, is that each country has unique needs, and community contexts vary. The shape of the demand curve for health care and the combination of health professionals to fulfill this demand are different in each setting, based on the demographics, health service delivery structure, and broader social determinants of health. The challenge, he said, is to find the right composition and number of health professionals to meet each country’s specific population needs.

Steve Schoenbaum, Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, raised a concern that perhaps classical economics is not the most useful perspective for analyzing the financing of HPE. To him, it seemed most reasonable to determine the population needs, determine how to meet those needs and what workforce is needed to achieve that goal, and then to market the right kind of workforce to the population. He provided the example of the emergence of nurse practitioners and physician teams; originally, these teams were very different from what was typically done in the overall marketplace. Therefore, specific marketing was required in order to show that the nurse practitioners could provide equal care as the physicians. Araujo responded that a classical economics perspective is useful in the sense that it helps one view the drivers and the market forces around financing HPE. From an economic perspective, he said, the market is functioning well; patients and health care workers make their choices to maximize their interests, seeking higher rates of returns, for example. He then emphasized that this market functioning does not lead to optimal allocation of resources, as the outcomes do not seem to be aligned with social return and public good. For this reason, said Araujo, the market needs to be regulated in order to achieve the desired outcomes.

A MODEL FOR FINANCING HPE

Erin Fraher, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Based heavily on Araujo’s work, Fraher presented a simplified model for understanding and exploring drivers and levers (or incentives) for financing HPE. As shown in Figure 2-8, meeting the needs of the population is on one side of the model and health professions education is on the other. Between them are the supply and demand market forces described fully by Araujo.

A more detailed look at the model is found in Figure 2-9. It shows an incentive structure for bringing new candidates into the educational system

SOURCE: Presented by Fraher, October 6, 2016.

NOTE: HCW = health care workforce; ROI = return on investment.

SOURCE: Presented by Fraher, October 6, 2016.

SOURCE: Presented by Fraher, October 6, 2016.

and how population needs include serving those in remote and underserved communities for promoting health as well as treating disease.

The two ends of the model are mediated by market forces that sometimes work and sometimes do not, she said. When the supply of health professionals does not match the demand of the population for services, or when the education does not meet the needs of the graduates, this is considered a market failure. These mismatches can be seen in Figure 2-10.

Guiding Principles

Fraher then called the participants’ attention to the one-page document found in Appendix B of this Proceedings of a Workshop. As a contributing author, she recapped the guiding principles in the document that represent what the authors believe is an ideal for what a well-designed health professions educational system would be founded on. These principles are noted in Box 2-1 and take into consideration health system transformations that

are putting new demands on the health workforce at a time of increasingly constrained financial resources. Such constrained resources are forcing health system leaders, employers, and governments to rethink their social and financial returns on investments for financing health professional education. This, said Fraher, is shifting the cost burden from the public sector

to the student, resulting in a stronger voice to students in how education is delivered, and pushing educators toward more innovative, cost-effective models for delivering education.

Taking a closer examination of the guiding principles, Fraher asked the workshop participants, “If we were to design a health professional education financing system, what would it look like in an ideal world?” It would be responsive to society, and it would reflect the population needs and not just market demands. It would also be transparent so the payers of education actually know what they are paying for.

As Araujo mentioned, the world invests less than 2 percent in health professional education (Frenk et al., 2010). Fraher recognizes the meager investment this represents, but reiterated Araujo’s point that despite the low level of investment, use of these funds may not be optimal. She wondered if greater transparency for knowing the return on investment would increase the effectiveness of the investment.

Another point raised by Fraher is the need to be nimble. Predicting the direction of the health system to ensure an adequately sized, trained, and distributed workforce is difficult at best; therefore, having the ability to quickly adjust education based on market signals would better synchronize education with health systems that are responsive to the population needs. It is not enough to read the market signals today when trying to train a professional through a pipeline program that is 5, 7, or 9 years out of date.

The ideal HPE financing system would also be valued by all its stakeholders. This includes the government that finances HPE, the individuals who invest their time and money into the education, and the systems—education and health care—that benefit from the financing.

The ideal HPE financing system also has to generate value, said Fraher, and consider a lifelong timeframe because fixing the health care system involves investing in the pipeline and lifelong learning. But most importantly, it must be ethical. If the market is sending incorrect signals, and students are taking on a huge amount of debt without the prospect of a job after graduation, the students are placed in a terrible position to pay back their student loan. Greater interconnections between education and health systems may be one way of limiting unethical practices that would potentially increase school enrollment and saturate the job market.

Identifying Gaps

With those few remarks, Fraher then turned to the audience for their input on what is missing from the guiding principles and for comments on the mismatches shown in Figure 2-10. She suggested that within the United States, there is a heavy focus on curative interventions rather than preventing disease and building health. This is represented on the left side

of the model. On the right side is health professions education and training that is heavily influenced by models of training, by policy, by licensure, by regulation, and by the faculty. Without adequately trained faculty, education is constrained on its ability to expand the workforce in ways that could respond to population needs. The market signals that influence individuals’ career choices in terms of their personal return on investment are shown in the interior of the model.

A mismatch between what is being produced through education and what the population needs can lead students to accrue large debts. Another mismatch is the weak demand for services in underserved populations where expensive care and fee for service are the norm. Additional mismatches arise between supply and demand because of faulty modeling predictions that cause a glut or a deficit of skilled workers for jobs in the health workforce. Fraher calls this lurching from oversupply to shortage.

Fraher then highlighted the skill gaps that are particularly relevant for rapidly transforming health systems. How do students and faculty learn about care coordination, patient engagement, population health, informatics, and working interprofessionally? Educators are being asked to move quickly in adapting the competencies needed for graduation while also being more cost-efficient, which is hard to do. This, said Fraher, is yet another mismatch.

A number of participants responded to Fraher’s request for input to the guiding principles and the model. The first commenter articulated the importance of considering who gets educated and who is educating, because this will determine what gets taught and how. In addition, when considering the “demand for services in underserved populations,” many from underserved communities do not have a voice or do not realize they can make demands, so looking beyond HPE to broader influencing societal factors is also important.

The second remark involved real versus perceived needs, how one defines those needs, and who defines them. Without clarity around the needs, it will be difficult to determine mismatches. The third comment concerned economics in terms of starting up lucrative new health professions training programs. While financially advantageous, they may be contributing to the oversupply of health workers. This statement led to a related observation by another participant on the issue of duplication within HPE that is unnecessarily driving up costs. The same participant also commented on the use of the word prevention. She believes prevention is still targeted at a disease model and it should be driving toward health, well-being, and prevention as the goal. The next remark echoed this desire to move away from disease models toward a system of health creation, which is well beyond what most typically think of as prevention. In the end, he said, it is about value and what that means within the model in terms of supply and demand.

Levers and Drivers

Following the participants’ remarks on the presented model and the guiding principles, Fraher then went on to describe potential drivers of HPE financing, some of which are shown in Box 2-2. Fraher requested that, throughout the course of the workshop, the workshop participants identify drivers missing from the list. Similarly, she asked the participants to look at the list of levers shown in Box 2-2 for other additional incentives that could realign or reshape health professions education financing. Fraher then handed the microphone over to Warren Newton, who led the next session that engaged workshop participants in table discussions for testing personally held assumptions about financing HPE.

EXPLICATING A MODEL FOR FINANCING HPE

Warren Newton, American Board of Family Medicine

Newton began by directing the audience back to the model in Figure 2-8 that asks whether and how the health labor market mediates the translation of population health needs to the actual health professions workforce and career choices. He then turned to the guiding principles in Box 2-1 and in

Appendix B of this Proceedings of a Workshop for the first of two table discussions.

His goal for the first discussion was to have the workshop participants share their own personal experiences among themselves that test the assumptions described in the guiding principles. Referring to the first discussion question noted in Table 2-2, Newton asked workshop participants if these were the right guiding principles, if there are any elements they would add, and if there is anything that participants need to keep in mind as they think about developing a system of the future of financing of HPE. Individuals reported their discussions to the larger group. Summaries of the responses are noted in Table 2-2; the comments noted in Tables 2-2 and 2-3 are those of the individual respondents and should not be considered a group consensus.

The second table discussion delved more deeply into the actors involved in health professional education financing. Newton presented a list of potential actors as follows:

- learner

- employer

- education system

- government payers and taxpayers

- community

- regulatory bodies and professional associations

- health systems

As with any reform, he said, there are human agents and institutions that stand to gain or lose from any changes introduced into a system. Newton reached out to the audience for their help in identifying new actors,

TABLE 2-2 Discussion on Guiding Principles for HPE Financing. Are these the correct guiding principles of the health professional education finance system? If not, what should be added and deleted, and why?

| Respondent | Affiliation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| John Finnegan | Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health |

|

| Respondent | Affiliation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Mary Beth Bigley | Health Resources and Services Administration |

|

| Zohray Talib | The George Washington University |

|

| Susan Scrimshaw | The Sage Colleges |

|

| Joanne Spetz | University of California, San Francisco |

|

* Newton challenged the audience to consider a timeframe for strategic planning, asking, “What is the right timeframe? Is it 5 years from now? Is it 30 years from now? Is it 10 to 15 years? What makes sense given the discussions taking place today?”

their influences, and their interests. The audience was given 7 minutes to talk among themselves in small groups before sharing their ideas with the others. Summaries of these responses are captured in Table 2-3.

Newton summarized the conversations saying he sees a pattern based on the ideas proposed by the various table representatives; it seems there is a need to get beyond superficial phrases and to disaggregate the list of actors. By doing this, the list of key stakeholders extend beyond the original eight actors to include philanthropy, patients, families, and others. Richard Talbott, representing the Association of Schools of the Allied Health Professions, offered the idea of dividing the actors into two groups: (1) those whose work actually moves the needle, and (2) those whose input is critical for initiating action. This way, it is not just an intellectual exercise, but instead one that will create actionable steps toward improved health and health care. Newton listened to the thought but also cautioned against working only with those who have clout, which could be very dangerous as certain groups would inevitably be left out of the conversation.

TABLE 2-3 Discussion on the Actors in Financing HPE. Are there any actors in financing health professional education that are missing from the list below? What influences do these actors have in reaching the guiding principles? What are their interests?

| Respondent | Affiliation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Mary Barger | American College of Nurse-Midwives |

|

| Mary Beth Bigley | Health Resources and Services Administration |

|

| Susan Scrimshaw | The Sage Colleges |

|

| Respondent | Affiliation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Robert Smith | Health Education England |

|

| Joanne Spetz | University of California, San Francisco |

|

| Zohray Talib | The George Washington University |

|

| Workshop participant | Unknown |

|

REFERENCES

Araujo, E. 2016. Tensions and challenges to adequately and efficiently financing HPE. Presented at the workshop: Future Financing of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, October 6.

Beciu, H. 2009 (unpublished). Capacity of health training institutions in Mozambique. Draft technical report. World Bank.

Department of Health. 2008. A high quality workforce: NHS next stage review. UK Department of Health.

Evans, T., E. C. Araujo, C. H. Herbst, and O. Pannenborg. 2016. Addressing the challenges of health professional education: Opportunities to accelerate progress towards universal health coverage. Doha, Qatar: World Innovation Summit for Health.

Fraher, E. 2016. A model for financing health professional education. Presented at the workshop: Future Financing of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, October 6.

Frenk, J., L. Chen, Z. A. Bhutta, J. Cohen, N. Crisp, T. Evans, H. Fineberg, P. Garcia, Y. Ke, P. Kelley, B. Kistnasamy, A. Meleis, D. Naylor, A. Pablos-Mendez, S. Reddy, S. Scrimshaw, J. Sepulveda, D. Serwadda, and H. Zurayk. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376(9756):1923-1958.

Hernandez-Peña, P., J. P. Poullier, C. J. M. Van Mosseveld, N. Van de Maele, V. Cherilova, C. Indikadahena, G. Lie, T. Tan-Torres, and D. B. Evans. 2013. Health worker remuneration in WHO member states. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91:808-815.

Liua, J. X., Y. Goryakin, A. Maeda, T. Bruckner, and R. Scheffler. 2016. Global health workforce labor market projections for 2030. Policy research working paper No. 7790. Washington, DC: World Bank. License CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25035 (accessed March 9, 2017).

McPake, B., A. Maeda, E. C. Araujo, C. Lemiere, A. E. Maghraby, and G. Cometto. 2013. Why do health labour market forces matter? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91:841-846.

McPake, B., A. Squires, A. Mahat, and E. C. Araujo. 2015. The economics of health professional education and careers: Insights from a literature review. World Bank Study. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/22576 (accessed March 9, 2017).

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2016. Health workforce policies in OECD countries: Right jobs, right skills, right places. Paris, France: OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing.

Palacios, M. 2002. Human capital contracts: “Equity-like” instruments for financing higher education. Policy analysis no. 462. Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

Preker, A., H. Beciu, P. J. Robyn, S. Ayettey, and J. Antwi. 2013. Paying for higher education reform in health. In The labor market for health workers in Africa: A new look at the crisis, edited by A. Soucat, R. Scheffler, and T. A. Ghebreyesus. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/13824 (accessed March 9, 2017).

Qin, X., L. Li, and C.-R. Hsieh. 2013. Too few doctors or too low wages? Labor supply of health care professionals in China. China Economic Review 24:150-164.

Roth, N. 2011. The costs and returns to medical education. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley.

Scheffer, M. C., and M. R. Dal Poz. 2015. The privatization of medical education in Brazil: Trends and challenges. Human Resources for Health 13:96.

Schumacher, E. J. 2002. Technology, skills, and health care labor markets. Journal of Labor Research 23:397-415.

Soucat, A., R. Scheffler, and T. A. Ghebreyesus, eds. 2013. The labor market for health workers in Africa: A new look at the crisis. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/13824 (accessed March 9, 2017).

Turner, A., P. Hughes-Cromwick, G. Miller, and M. Daly. 2013. Health sector job growth flat for the first time in a decade. Labor brief 13-08. Ann Arbor, MI: Altarum Institute.

Vaughn, B. T., S. R. DeVrieze, S. D. Reed, and K. A. Schulman. 2010. Can we close the income and wealth gap between specialists and primary care physicians? Health Affairs (Millwood) 29(5):933-940.

Walsh, K. 2013. Cost and value in healthcare professional education—why the slow pace of change? American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 77(9):205.

World Bank. 2011. World Bank country status report, Togo. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTAFRICA/Resources/AHF-fixing-labor-market-leakages-getting-more-bang-for-your-buck-on-human-resources-for-health.pdf (accessed January 20, 2017).

This page intentionally left blank.