3

Understanding and Applying a Model for Financing Health Professional Education

ANALYZING TENSIONS

Warren Newton, American Board of Family Medicine, opened the session by explaining the purpose behind using the debate pedagogy in education and for analyzing tensions in health professional education (HPE) financing at this workshop. Debates are a way of analyzing provocative questions, he said. They force a group to reflect on issues that are at times contentious, and debates can also be presented in a broad manner to cut across multiple professions and settings. In addition, said Newton, debates take health professionals out of their comfort zone; many feel that debates are something that lawyers do, not health professionals. Lawyers and the discipline of law teach students to come to the truth through structured arguments and debates. Such debates can be used to prepare health professionals and their students to be critical thinkers and effective communica-

tors; these are particularly valuable skills given the complexity of today’s health care environment (Hall, 2011).

Understanding the Tensions in HPE Financing

The arranged debates gave the participants a chance to look at tensions in the model presented by Erin Fraher that drew from concepts discussed in Edson Araujo’s talk. For example, should public spending on HPE be significantly increased? And is it acceptable to demand a social return on investment from health professional schools? These are the sorts of questions the group will grapple with during this session in the form of a debate, he said.

The debates began with a vote on the proposition followed by 4 minutes of arguments by each of the two debaters. Newton emphasized to the workshop participants that the debaters were not necessarily arguing what they believe, but rather the side they were given to represent. Following the debate, there was a group discussion and a revote to see if anyone changed from their original position. Finally, each debater spoke about what they really think regarding the debate proposition. Below are remarks from the workshop participants in response to the proposition.

The First Debate

Newton began by introducing the two debaters, Ann Cary of the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Nursing and Health Studies, and Patricia Hinton Walker of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. After both debaters presented the arguments either in favor or opposed to the position, Newton opened the floor for participant reactions and discussion.

Participant Perspectives

In reflecting on the proposition shown in Box 3-1, John Finnegan, representing the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health

(ASPPH), stated he believed the challenge is to demonstrate value and show the average person a guaranteed systemic change. He thinks that in the end, the goal is not to just add money to HPE, but rather to make fundamental systemic changes and improve alignment. Despite that, Finnegan feels that public expenditures should be increased. He was reluctant to agree to doubling it immediately, but also cautioned the group to not wait too long; 2030 is not soon enough, he said. While Finnegan endorses financing HPE, it must not add to the national debt burden, which means making some fundamental systematic changes about where and how the investments are made.

Zohray Talib, The George Washington University, followed Finnegan’s remarks by saying she thought the question could be deciphered in different ways. When she read it, she was thinking from a global perspective about whether or not there should be a reliance on public versus private expenditure to expand and improve health professions education. For example, in the case of Kenya, where nearly half of health care expenditures come from the private sector, why should there be a reliance on the public sector? She suggested that the private sector, which is well resourced, could and should also contribute to workforce training. She felt the pressing question is how can the input and investment from the private sector be optimized within health systems and health professions education?

Bjorg Palsdottir, representing the Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet), continued with comments from a global viewpoint and specifically from the perspective of someone born and raised in Scandinavia, a region with strong health outcomes and where health care and education systems are mostly government funded. While government funding does not necessarily translate into high-quality education, it can increase equitable access to HPE and positively influence service delivery, particularly in underserved regions. While the private sector has a role in funding HPE, it can distort outcomes, particularly in systems with weak regulatory frameworks and inadequate quality assurance systems. If desired education, health workforce, and health system outcomes are clearly defined and collaboratively agreed on, and when accountability and quality assurance mechanisms are in place to enforce these desired outcomes, then it is possible to take a step back to determine how education is best paid for.

Miguel Paniagua, representing the National Board of Medical Examiners, thanked the debaters for initiating a conversation in the Forum about the end of life and life-limiting illness—something that Forum members have not discussed in their meetings until this point. The one-page document presented and discussed by Fraher (see Appendix B) alluded to an increased complexity of patient cases without actually mentioning end-of-life care.

Paniagua acknowledged that in the United States, end-of-life and pallia-

tive care are not often handled well. Many older patients are dying in hospitals, sometimes in the intensive care unit. This involves a large cost that will only increase as demographics shift and the overall population ages. In looking at the bigger picture, Paniagua wonders who is being educated and the type of education they are receiving, and if this problem might be addressed if the education focused on care provided outside of a hospital.

Satya Verma, representing the National Academies of Practice, pointed out that even if expenditures on HPE were to double by 2030, that does not necessarily mean the needs of society will be met. He understands the emphasis on chronic care but thinks a larger focus should be on preventative care to diminish the need for chronic care later.

Reflection on the previous comments led one participant to remark that much of the conversation is about a return on investment. He asked if the current investment in HPE was being effectively used to accomplish its objectives. There is a very strong case to be made for high productivity and a strong return on investment particularly when public funds are used to support the education. In those cases, rigorous criteria are needed to measure outcomes on investments, he said, and this may involve closing some long-standing institutions that are not demonstrating a return on expenditures.

Debater’s Comments

Warren Newton then directed a question to the first debater, Ann Cary from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing who argued in favor of the debate proposition. If public spending on HPE was doubled, would it be possible to spend the money rapidly, effectively, and efficiently?

Cary said she began her debate argument by emphasizing the need to look at the return on investment. She also talked about recreating the product from HPE that is competency based as opposed to disciplinary based. She thinks HPE must be reexamined along with the whole notion of health care delivery. Cary remarked that it is very difficult for health professions to deliver quality competency-based education. In her view, those within HPE should look inward in order to improve competency-based education. To do this, those within HPE should ask what are the necessary competencies? What are financers and payers of education willing to invest in? And what are they willing to give up or deploy elsewhere? Most importantly, how are those investments going to make a difference in the health of our communities?

Patricia Hinton Walker, the other debater, offered additional points from her personal perspective growing up in the rural Midwest, not from her professional perspective in her role as an education and higher education administrator. Her comments revolve around the public perception

of education. One is that there appears to be a lot of duplication in the educational system. And the other general belief of some individuals is that educators have easy jobs with banker hours and summers off at a time when most industries are pressing for greater productivity and higher demands on their employees. Both of these comments point to a possible public perception from those who would be paying for the HPE that it could be conducted more efficiently.

Final Remarks

A final audience comment came from Emilia Iwu from Rutgers University, a global health nurse faculty representing the Jonas Center for Nursing and Veterans Healthcare. She looked at HPE financing from a global perspective. Developing countries that use public funds to pay for the education of their health professionals lose out when fully trained professionals leave their country to seek employment in more prosperous nations. With this recognition, she suggested that some investments should go to those areas of need where such health professionals are actually being trained.

Warren Newton then turned to the two debaters to give them an opportunity to share any personal reflections on the debate proposition. Cary spoke from her experience distributing roughly $11 million in federal grants for workforce production. The grants had a significant positive effect on producing health care workers. She reinforced the idea that education must anticipate the needs of the population and create a workforce that matches those needs. For this to work, systems would have to be nimble. Systems must be used in a way that allows everyone to capitalize on those investments. Cary also believes in private investment. “I think public good is not just supported by public funds,” she said. “It has to be a public–private partnership.”

Newton reiterated Cary’s call for being future oriented before asking Patricia Hinton Walker for her final remarks. Hinton Walker commented that where she works, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), education is provided through public funding. What is important, she added, is the payback. There are a variety of different ways that public expenditure could be viewed. Hinton Walker sees it as “payback with heart” that is not just a token gesture but a true investment in communities and, as it is at USUHS, a return on investment in the nation. That means recruiting students and faculty from underserved communities who are more likely to aid and support the communities from which they came. Shifting slightly, Hinton Walker then brought up what she called a perception in some rural settings and growing concern in other settings of the privilege of tenure that she observed in her previous positions as a dean in both private and public sectors. Tenure can affect the rate of change and

at times the quality of education and whether or not it is future oriented. Walker acknowledges the tensions this causes between providers of education and its payers who question its value and accountability.

Hinton Walker then agreed with Cary about her call for public–private partnerships before bringing up a need to address how much interest is paid by families and students on their loans. With that final remark, Newton introduced the second debate.

The Second Debate1

For the second debate, instead of having two individuals at the front of the room arguing opposing positions, participants on one side of the room argued in favor of the proposition, and participants on the other side of the room argued against the proposition. Newton then gave participants 8 minutes to discuss with others in their immediate vicinity a set of arguments in favor or against the proposition found in Box 3-2.

Following the small-group discussions, Newton called on the side arguing in favor of the proposition to put forth one argument at a time.

Debater Arguments: In Favor of the Proposition

The first person to argue in favor of the proposition expressed her opinion on the importance of definitions. Defining the social return on investment in terms of population health brought her back to the model shown in Figure 2-8. There are population health needs, demands, supply, and education along with some market failures. Nestled within all of these are the social returns. But of course, there are market forces in the private sector that will influence decision making at all levels, preventing social returns. The question she raised is how will market failures be counterbalanced if not with public funds? That is her argument in favor of funneling public

___________________

1 The views expressed during this debate session are not necessarily the opinions held by the speaker as each participant was assigned one side of the debate.

funds to institutions demonstrating a social return on investment (ROI). It is the public funds and public subsidies that somebody needs to care about.

The next commenter, arguing in favor of the proposition, built his argument saying the risks are enormous if public investments are not made addressing the issues brought up previously about equity. There is a real sense that if public money is used, there must be fairness to taxpayers providing the funds. To him, that is a powerful message from a human level.

Another comment from this side offered an additional view in favor of the debate proposition that it would incentivize change to occur. Like others, she and her colleagues at her table took the time to define social return in terms of meeting the needs of the community. The alternative is to provide funding that puts no pressure on the system to change. Agreeing with this proposition would be an incentive for changing the system in how HPE is conducted.

Debater Arguments: Against the Proposition

Newton then turned to the other side of the room that argued against the debate proposition. Their first commenter proposed his case saying that measuring a social return is nearly impossible. Even if it were possible, it could only be done over the long term. Public funds that flow into HPE institutions flow on a continuous basis, at varying funding levels. He asked, what baseline will be used? How are the institutions going to be judged on whether the organization is creating a social return, however it is ultimately defined? Since it is basically impossible to define it, the proposition is impossible to implement, he concluded.

A follow-up argument for the side arguing against the proposition stated that the proposition itself is faulty because all education has a return for society. The moment extra conditions are added, regardless of how the social ROI is defined, that will drive behavior. Individuals and organizations will follow the path to get the money, and who is best positioned to change the course of an institution but those schools that have the most resources?

Schools that can afford to hire the best marketers and have the best lobbyists to convince government that their organization is meeting the definition exactly will be the ones who receive the funding regardless of how the ROI is defined. This perverse incentive may not support those schools that are perhaps doing what the funds were intended to support, which is to provide health care that fulfills an unmet social need. Those institutions tend to be the ones with the least resources.

The next commenter agreed with the previous point then added that by supporting this proposition, the concept of social return and the goal of education is being put into the political fray. What one person might define as a social return, another would not. For example, she asked, does family

planning education have a social return? Policy makers would disagree on the answer to this question. This brought her back to the previous argument that certain organizations with resources will game the system. The result is not a discussion on improving the social ROI but a highly politicized debate over money.

Following this last debate comment, Newton opened the floor for general comments from the audience.

Participant Perspectives and Reactions

One participant remarked that it is all in the definition. The ability to stimulate the economy through private entrepreneurial action is another means of social return. This stimulated a thought for John Weeks from the Academic Collaborative of Integrative Health who was reminded of a time in the 1990s when funding became available within integrative health and medicine. This drastically changed the way a number of medical schools viewed integrative health. They went from denying and dismissing the field to starting up integrative medicine programs that pulled funding away from those programs that had been working in this area for years.

The next participant comment suggested that it might be more realistic to change the proposition to a social and economic return. It is how economics affect the individual, particularly those who are in less densely populated areas that are often overlooked when it comes to getting services. These people are feeling disenfranchised as they pay more but receive less care for their economic investment.

Susan Skochelak, representing the American Medical Association, raised two points that troubled her about the proposition. First is the fact that the public funds would go to institutions. She does not necessarily see institutions as agents of change, and wonders if it would be better for communities or individuals to directly receive funding to decide how best to invest in improving outcomes. In addition, she said, it is easier to track use of funds and accountability with individuals and communities than it is to track accountability within institutions.

Her second comment referred to both the propositions as she was reminded of the fact that in the United States, there is an imbalance in terms of the amount of money going to health care and HPE as opposed to addressing the social determinants of health. Rather than funding health professions institutions—even those that are demonstrating a social return on investment—a better approach may be to fund improvements in social factors that may return better value on health through supporting healthier communities.

Palsdottir disputed an earlier claim that it is not possible to measure a social ROI. This is actually being done, she said. It is difficult to measure

the social return on investment of health workforce education, but there are some opportunities, particularly for community-engaged health workforce education. Achieving real change requires the involvement of institutions as change agents in collaboration with communities. The data collection can involve tracking where the graduates go to work, their influence on policy, and which graduates positively affect individual and population health. One of THEnet’s current studies submitted for publication is comparing graduates from two schools in the Philippines—one with a social accountability mission and the other a more traditional educational institution. The authors are finding differences in health-seeking behaviors of the patients served by the graduates who underwent different forms of training. For example, the providers from the socially accountable schools have better educated patients who are more likely to give birth in a health care center. Palsdottir admitted that the study is not a randomized trial, but it is a start to building the evidence. The goal is to strive for more evidence, she said, whether the data is perfect or not, and when measuring the social return on investment, it is important to start by asking communities what they value then work toward that as an end goal.

Elizabeth Hoppe, Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry, suggested that additional insights could be gained by using behavioral economic theory, which incorporates some elements of psychology and some newer modeling approaches. This could help develop a deeper appreciation of human behaviors that may not be quantifiable. Fraher followed up this comment with the observation that producing the data does not always equate to affecting change. In North Carolina, they have been studying where medical students work after graduation for the past 25 years. They find that 2 percent of the medical students end up in rural primary care in North Carolina. While the new hope is that changing admissions will alter this statistic, there has been little to no movement for the past two decades in which the same unchanged data has been published. But she also cautioned that even with the best data, people will still behave irrationally. With that, Newton closed the debate session.

LEARNING FROM EXAMPLES OF EFFECTIVE HPE FINANCING

Moderator Overview of Mismatches

Joanne Spetz, University of California, San Francisco

Joanne Spetz moderated the next session that was designed to explore the financial effectiveness of the health professions and education through specific examples. She opened with some remarks that laid out the economics of education and health care through mismatches that were outlined in Chapter 2 (see Figure 2-10).

Supply and Demand

As a health economist, Spetz is well positioned to more fully explore the discrepancies between supply and demand for health workers. A theoretical scenario, she said, is the sale of labor whereby a health professional applies their skills in any number of different places. Within this ideal situation there would be multiple health workers selling identical services in a perfectly competitive market. The seller and the consumer would have access to accurate and timely information about the quality of the services and prices, and there would be freedom to enter or exit the market at any time. If this was truly possible, she said, then prices would naturally adjust and markets would equilibrate on their own. For example, if there was a labor shortage, the price for services would go up because there are not enough people selling the product. That would encourage more people to sell their services which in turn would balance the shortage.

Spetz then turned to the audience and asked if this sounded like health care in any way, shape, or form? In answer to her own question, she responded “no.” Health care fails in virtually every one of these categories because it does not follow classical economics.

Health care fails in these categories for several reasons, said Spetz. There are a limited number of buyers of health professionals’ work. In many cases, there is one clinic in a neighborhood, one hospital in a community, or only a couple of employers, which creates limitations on buyers. The counter to this is that individuals might go years or decades not requiring the services of the health professional, and then suddenly an acute injury requires immediate attention from a specialist. However, she said, the times when those services are needed are limited.

Other factors that limit the supply of health professionals are the long training requirements that are further lengthened by requirements of certification and licensure to practice. But in terms of quality control, regardless of licensing, consumers would still want to know that their practitioners have sufficient training before paying them for a service—a service that varies in quality across providers and health facilities.

There is also a lack of perfect information. This deficit of high-quality information about each of these factors is one of the most inherent problems in health care. One could argue that in many markets, the Internet is helping to solve the information gap, but in health care, there still is a noticeable lack of information. For example, uncertainty remains around which medication might best control the blood pressure of one person versus another. Decisions are made through trial and error because perfect information in health does not exist.

Finally, health practitioners have little freedom to enter and exit the profession owing to financial investments in education or establishing a practice.

Mismatches

These are some of the pieces that result in the mismatches described earlier that create gaps between population needs on one side and demand for services on the other. There is a mismatch between what people need and what they can afford because they do not have the money or insurance to cover the expenses.

Spetz went on to describe the oddity of health insurance where incentives are often misaligned. Instead of encouraging interventions that might provide the best long-term health and wellness, health insurance structures frequently favor expensive treatments and diagnostics.

Public funding can also be mismatched. In this way, health agency funds might not be well aligned with true population needs. Such a disconnection can be challenging to overcome for a variety of practical and political reasons as well as for completely unknown reasons that were discussed by Fraher previously.

Next there are wage issues where an agency or organization does not have the budget to support the salaries required to get the workforce supply where it is needed. These are examples of market failures where the revenue for hiring does not match the actual need, so prices and wages are not adjusting. Again, a mismatch is created between population need and demand for health workers.

In looking at the production side, a mismatch can create underemployment, saturation of labor markets, or both simultaneously when health workers are not where they are needed. Of course, said Spetz, individuals’ decisions about where to live are much more complex than the classic economic model of money.

There are also information issues on how to find an open job. Spetz gave the example from Kenya where roughly 8 years ago, the unemployment rate of nurses was incredibly high due largely to an information mismatch between the Ministry of Health and the workers they hoped to recruit. Many nursing candidates did not even know the positions were open. In addition, there was general inefficiency in their administrative structures. Ministry workers took so long to move applications through the hiring process that by the time the candidates were placed into jobs, they had already given up and sought employment in another field or another country.

The last set of mismatches involves graduates who might not be trained in ways that meet the needs of their population and therefore remain unemployed with large debt. To add to the mismatch, licensing exam requirements might not be aligned with what employers currently want or need in their workforce. This can happen because different systems might not be sharing information that highlights the imperfect information problem.

Other imperfect systems are bureaucratic organizations. In a sense, each

organization has its own master and is its own living, breathing political entity that could call into question their accountability and trustworthiness. Spetz used higher education institutions as an example. Higher education institutions have a business mission they are trying to achieve that may be heavily focused on their own sustainability. This means they will use the system to make themselves financially viable and at the top of the rankings. Pushing for these goals may or may not be aligned with what employers are saying they really want to see from the graduates.

There are also issues with access to loans. Such financial support can be extremely beneficial to help provide opportunities for people who would otherwise be unable to make the large investment in education. Similarly, loans for any kind of a business investment can be a very good thing. But there are also many examples of loans being given to students who are pursuing professional goals that are not going to lead to a job. In the United States, this can happen in some of the private vocational schools that are training people, for example, to obtain medical assisting certificates that employers do not necessarily recognize or feel they need. This brings into question the value of the education while the student grapples with thousands of dollars of debt having been assured that they are investing in a great career opportunity. These kinds of mismatches again underscore the problems relating to imperfect information.

Spetz asked the audience to consider the points she raised while they hear from the next three speakers who each presented a different supply- and-demand example from HPE. She challenged workshop participants to think about the spoken or unspoken underlying market failure that the innovative programs described are trying to address. How might the programs stimulate ideas for other approaches to deal with similar market failures, similar problems, and similar challenges to meeting societal needs? In the end, she said, meeting society’s needs is the main goal. The goal is not to emphasize all the different steps in the system where there is a mismatch between what the education system is putting out and what the education system is asking individuals and taxpayers to finance.

Spetz then introduced the three speakers. The first presenter, Wezile Chitha, is a physician and health economist and is the dean of health sciences at Walter Sisulu University in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. The second speaker, Robert Smith, who has a background in finance and workforce planning, is now the director of Strategy and Planning at Health Education England. The third presenter was Richard Valachovic, president and chief executive officer of the American Dental Education Association. Each of their presentations are summarized in the sections below.

Financing Rural Medical Education in South Africa

Wezile Chitha, Walter Sisulu University

Wezile Chitha began by saying that Walter Sisulu University (WSU) started about 30 years ago as a traditional curriculum during the apartheid era when they were part of the Republic of Transkei. They are now one of the only two rural-based medical schools in South Africa.

Soon after starting, Chitha and his colleagues realized they needed to redefine their mission based on the experiences of the first class going through their curriculum. This involved moving to problem-based learning together with community-based education. They agreed to invest in community partnerships, integrate community service into all their academic programs, and emphasize the primary health care approach. Much of their work and their mission was informed by international efforts such as the Alma-Ata declaration (WHO, 1978). They see themselves as advocates for equity, both in education as well as in the health sector.

WSU’s motto is “excellence through relevance,” and their guiding principles reflect their beliefs. A key principle is that the academic platform must be built on the partnerships between the university, the community, and health care service providers. That essentially means having the community involved at all levels of the university including decision making, program design, evaluation, teaching, and essentially all elements that are academic in nature.

Education and Training

WSU has a province-wide platform upon which it can designate facilities used for training. This platform has expanded and includes all levels of care from households, clinics, community centers, and district hospitals through tertiary-level facilities, although the tendency is toward using secondary and primary care facilities.

The types of students that WSU selects are generally drawn from underserved communities, predominantly from two rural provinces in South Africa, namely the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal. While those are the primary areas where its students are from, it is an open application process so others from outside those regions can also apply. Community members participate in interviews of the students, and personal attributes are scored and considered equally with academic performance. A rural high school education is used as a proxy for selecting students from the desired background.

WSU’s curriculum is based on a primary health care philosophy that is informed by health and social needs of the community. Students have early clinical exposure and a heavy focus of learning in the community. Basic

sciences, clinical medicine, and population health are integrated throughout the entire 6-year education program. It is implemented using problem-based learning and a philosophy of student-centeredness and self-directed learning.

Financing Education

Chitha next described the university funding source that comes primarily from government. This funding flows from the Department of Higher Education and Training. Set up as an innovation in 2009, the department was an attempt to focus on higher education and its role in the development of the country and the economy of South Africa. Part of that mandate incorporates medical schools into the universities, which is why the medical school reports through the university to that department. However, the platform for training is with the governments so the medical school also works closely with provincial governments. In addition, there is the National Department of Health providing policy and guidance to the provincial government as well as the service and funding relationship between the medical school and the provincial government.

The funding structure for the medical school is predominantly composed of a block grant making up 48 percent of the total support. There are also conditional and earmarked grants (30 percent) that consider the size of the university and the proportion of disadvantaged students enrolled. Given that more than 80 percent of their students fall into this category, WSU receives a large proportion of their support (30 percent) from this source, which they use for building infrastructure, developing research, and improving the clinical training platform.

Financial assistance from the Department of Health comes in conditional grants to the government through two major platforms: the National Tertiary Services platform, which is called the National Tertiary Services Grant, and the Health Professionals Training and Development Grant. These grants go to the provincial governments to ensure that the academic health platform is appropriately developed. The final category is student fees. This makes up 22 percent of the current funding in the medical school. This has been increasing over the years, putting additional burden on students and their families. Keeping fees low for students has been an increasingly difficult task. With declining subsidies, universities have been shifting the burden of costs to students, especially those universities that do not have additional income from sources such as research contracts, the sale of goods and services, and private gifts and grants, such as WSU. Of all the universities in South Africa, WSU depends most heavily on state subsidies.

Chitha called out one important statistic within the student fee category, which are the bursaries (or scholarships). While it is currently at 37

percent for the medical school, this funding used to be much higher. With the economic downturn since 2008, they have seen a decline in scholarship funding from the government. Government provides 35 percent of their bursaries illustrating the school’s dependence on government funding. With less scholarships and a greater reliance on student payments, this has created increasing debt for the graduates. Chitha believes that student debt will have negative implications for retaining graduates within rural communities.

Currently, medical graduates from WSU overwhelmingly remain in rural and underserved communities. Seventy-three percent are practicing in rural areas of the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal that are the feeder provinces for the school, while only 16 percent are practicing in large cities. Sixty percent of graduates enter general practice, while 35 percent have elected to specialize within medicine.

Given the diminishing funding for education and the value provided for society through education, the national government has been looking into social contracts with the private sector. The Ministry of Health is now calling private companies to discuss the need for the companies to contribute toward health professional training and development. Chitha emphasized how their medical school gives back to the community it serves. And while WSU is dependent on the government, it is trying to ensure that what it produces is relevant and responsive to the needs of the communities from which it is recruiting their applicants.

Meeting the Need for General Practitioner Roles by Use of Clinical Pharmacists

Robert Smith, Health Education England

Robert Smith framed his presentation around Health Education England (HEE) that holds a £5 billion pound (roughly $6.2 billion) training budget for educating clinicians within a fully state-funded health system. He offered some insight into how HEE attempted to solve some of the mismatches that were discussed in terms of the model seen in Figure 2-10. His presentation was designed to explore the causes of those mismatches and perhaps move toward validating the model going forward.

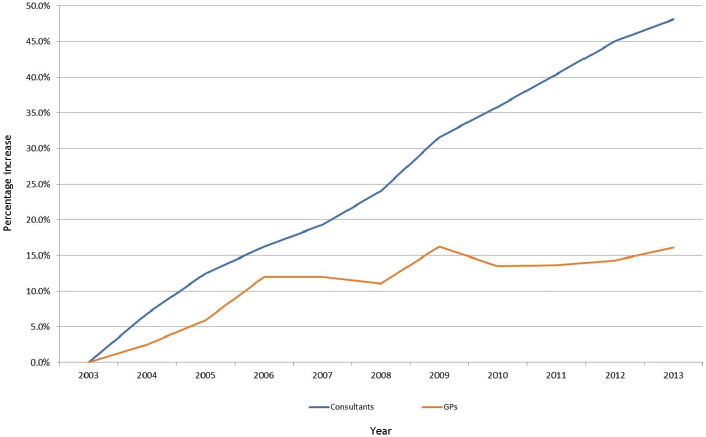

What was the problem HEE was trying to solve? Basically, it was a mismatch between a need for more clinicians working in primary care in the community sector and the supply produced through education. Figure 3-1 shows the history of the growth of the medical workforce in England between 2003 and 2013.

Smith reminded the workshop participants that any growth in England happens as a consequence of publicly funded education. Because the state

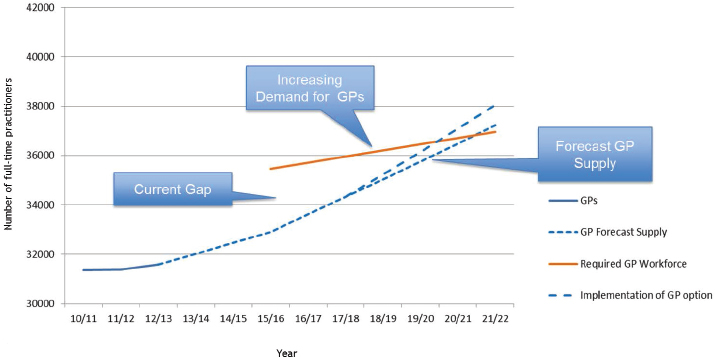

has the money, it, at least in theory, has the control over entry into the workforce. Despite its policy goals and its attempt to meet the population need, Figure 3-2 is an indication that the supply of general practitioners (GPs) is not meeting the current or projected demand.

There is an absolute limit to how quickly HEE can produce GPs as primary care clinicians. Smith admitted that when he and his colleagues began they thought the primary issue was funding for training. They thought inadequate funds were being put into creating GP training posts, so the logical solution was for the state to fund more posts and invest in the infrastructure required to support these posts (including physical capacity, such as consulting rooms, and educationalist capacity, in terms of “faculty”).

That is when HEE discovered that the limit to the number of posts and physical capacity was only one of factors limiting the supply. In 2014, there were roughly 2,700 posts. HEE created 400 more. They advertised

NOTES: GP = general practitioner. This figure shows the relatively low historic growth to general practitioner workforce. Postgraduate medical education for both secondary care and primary care are directly state funded. Notional funding could be deployed to policy priorities, but there has been a threefold variation in rate of growth (48 percent versus 16 percent).

SOURCES: Presented by Smith, October 6, 2016 (adapted from HSCIC, 2014). Copyright © 2016, Re-used with the permission of the Health and Social Care Information Centre, also known as NHS Digital. All rights reserved.

NOTES: GP = general practitioner. The figure shows the current shortfall versus minimum “need” of 3,000 full-time employee general practitioners. The shortfall versus the funded demand for general practitioners is not known. Modelling of additional activity requires a minimum of a further 1,000 full-time employee general practitioners. The general practitioner supply alone could not meet the minimum need until 2020 or 2021.

SOURCES: Presented by Smith, October 6, 2016 (adapted from HSCIC, 2014, and HEE, 2017, unpublished). Copyright © 2016, Re-used with the permission of the Health and Social Care Information Centre, also known as NHS Digital. All rights reserved.

for 3,100 trainees but only received enough applicants of the right quality to fill 2,700 of the available posts because people chose to pursue training in other medical specialties. It was not until Smith and his colleagues had addressed what they thought were the root causes of the problem that they began to confront the sorts of issues that are called to light in the model (see Figure 2-10). This led Smith and colleagues to ask relevant questions such as, What is it that should be studied? What are the returns? Why might someone want to be a GP?

By offering strong incentives, Smith believed they would reach 3,250 traineeships and increase the total number of GPs. However, in analyzing the needs of an aging population—with increasingly greater complex medical problems—it was found that the GP supply was not growing at a rate that could meet population needs until roughly 2021. This is not good news for the health sector, the state, or the government trying to implement health care policies.

Smith and his colleagues calculated an expression of need based on use of the system by the population and including epidemiological factors. But, said Smith, they were not certain at the time that there would be jobs for all those qualified GPs (because of the mechanisms of the service payment system). Given this situation, Smith and his colleagues moved to a multiprofessional team-based approach. While some might argue that is where they should have started, Smith and his colleagues came to this decision by being forced to develop an innovative solution—a decision based on what is available, not on what is lacking.

One of the professions that appeared to be producing a surplus of graduates was pharmacy. As an interesting side note, Smith pointed out the large number of fee-paying, debt-based pharmacy schools calling to light another mismatch in this example.

Through this demonstrated need, HEE received a government commitment to the idea of supporting a multidisciplinary, multiprofessional primary care team. HEE is committed to having 10,000 clinical professionals of which 5,000 would be doctors.

HEE then commissioned a study led by Professor Martin Roland, who is a GP and an academic. He looked for good examples of multiprofessional primary care practice. This is important in trying to generate public and professional support for the idea that a multiprofessional team can provide high-quality care to the same standards as they would expect from their doctor.

After cataloging numerous positive examples, it was time to financially support the effort. UK’s National Health Service (NHS) England, which has the country’s health budget of £100 billion pounds and HEE at £5 billion, built a strategy for how to improve primary care and meet the primary care needs of the changing population.

The clinical pharmacist program is one aspect of this wider strategy to meet those needs. In it, registered pharmacists receive additional training to provide direct patient care. In an attempt to avoid unnecessary tension, the promoters of the program consciously avoided using the word substitution in describing the program. And while pharmacists are not trained to cover all the jobs of a GP, they can carry some of their workload.

The candidates for the program are experienced pharmacists. It is not about retraining excess graduates for something they are not ready to do. These individuals must have independent prescribing privileges, and have likely been in practice for multiple years.

Because they are already in a practice, the candidates receive in-service training. It is not an academic exercise. The trainee is in a practice already learning how to function on a team while improving his or her skills as a clinician. There is a specifically designed national learning pathway and

program with the University of Manchester, creating a homogeneous program across the country.

In thinking through implementation of the team-focused care model, Smith emphasized that they did not want to turn this into an academic exercise. It also had to be sold to the public and to the different professions and the pharmacists.

Some pharmacists are not fully comfortable interacting with patients, which is almost second nature to GPs. The program is structured so each person is assessed upon entry to determine their skill set so that it can be further developed to offer relevant patient services.

Cost and Impact

There is an 18-month training program costing roughly £8,000 pounds or roughly $10,000. It is fully state-funded by HEE. Smith then looked at the demand side, saying it is fine to build up the skills of the workforce but important to ensure there are jobs for all the newly trained workers.

During and after the training, there are 3 years of subsidized employment that go from 60 to 40 to 20 percent, and then no support for the fourth year. The program started with a 50-person pilot, and Smith said it was a tremendous success. This led to the first cohort of 470 trainees who are currently in training. The total cost to HEE is £3.5 million pounds ($4 million) and NHS England is paying £31 million pounds over a couple of years. While the price tag is high, Smith is hopeful that the program will lead to significant change in their system that better supports population needs.

This program has received support from GPs and others. While it is currently state funded, the hope is that eventually the value and ultimately its cost will be borne by employers or the student themselves. One risk is that the practice side of the health sector looks to hire other clinical pharmacists as a human resource strategy rather than training their own and the profession could therefore fail to meet population needs once state funding came to an end. Smith left the audience with two questions to ponder. Should such a program become permanently state funded? If so, what mismatches might it create?

Financing Dental Education

Richard Valachovic, American Dental Education Association

Valachovic started his presentation with contextual remarks about dental care and the dental education markets. There are about 160,000 practicing dentists in the United States. Schools currently graduate roughly 5,500

new dentists each year. Ninety percent of dentists are in private practice, leaving only 10 percent for everything else that includes faculty teaching, military service, public health, and all other forms of dentistry.

Understanding the Context of Dentistry and Dental Education

Roughly 85 percent of dentists are in 1- to 2-person private practices. They work in the sorts of bungalow practices that many view as typical within the United States, although there is a building trend toward the creation of group practices.

Unlike other health professions such as medicine or physician assistants, 80 percent of dentists are generalists leaving only 20 percent who pursue specialties such as periodontics and orthodontics.

From a coverage perspective, less than 50 percent of Americans have any kind of dental insurance. But in truth, said Valachovic, dental insurance is really a misnomer. Nobody has truly risk-based insurance; it is just a dental benefit. Those who do have the benefit have copayments, deductibles, and annual limits as to how much they can be reimbursed for their care or prevention.

Dental care through Medicaid has been an option for individual states to select or reject. One exception is under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; dental care became an essential benefit for all eligible children in the United States. This one policy has already demonstrated an incredible impact on the dental health of children in Medicaid populations. Although it still is an optional adult benefit, in Massachusetts, there was a provision for cosmetic repair of the upper six teeth. The idea is that repairing these visible teeth will improve that person’s chances of getting a job.

Overall, those in the United States who can pay for dental care generally do well, but access to care for the rest of the population remains a considerable challenge.

Valachovic then described a dental education and a dental practice perspective. The success or failure of dentistry is determined by one-tenth of a millimeter—a restoration, the placement of an implant, and a variety of other procedures a dentist performs relies on the accuracy of one-tenth of a millimeter. When dentists discuss well-being and wellness, it can be compared to the kinds of compulsive behavior dental education must instill into their students so they understand the importance of one tenth of a millimeter within the work they will be asked to perform.

In total, there are roughly 500 million patient encounters per year. Dentists typically see patients when they are well, which means dentists have an opportunity to engage in preventative care. There is a desire among dentists and their leadership to build on this aspect moving forward.

U.S. national expenditures in dentistry are about $113 billion per year.

Putting that into context, this is roughly equivalent to expenditures for outpatient cardiac or outpatient cancer care. Valachovic then reminded the audience that the National Institute of Dental Research was one of the three original institutes at the National Institutes of Health because the main reason for U.S. draft deferments since the Civil War was poor dental health. It was called the 4F, referring to the four front teeth. Having four front teeth was mandatory to be able to pop open gunpowder cartridges in the Civil War. That requirement remained through Iraq and Afghanistan deployments and continues to be a considerable problem. In fact, the need for emergency or urgent dental care was a major reason why some troops were not deployed during the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts.

There are presently 66 dental schools in the United States. Roughly half of those are public and half are private. Schools have three major sources of revenue and expenses that include tuition, clinic operations, and research. Essentially most clinical operations occur within the footprint of the dental school, although training can take place outside of the school. But unlike medicine, nursing, and pharmacy that interact within the academic health center, dental schools are relatively self-contained. Tuition now drives much of the education and clinical training activities. Where public schools used to be state supported, most have lost this support. There are some public dental schools where the tuition is higher than some of the local private schools, which has become a problem.

Dental Education and the Guiding Principles

Valachovic then addressed the guiding principles described in Appendix B to raise concerns within dentistry and dental education in the United States. He started with disease burden. There are three major health challenges in dentistry that include dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancer.

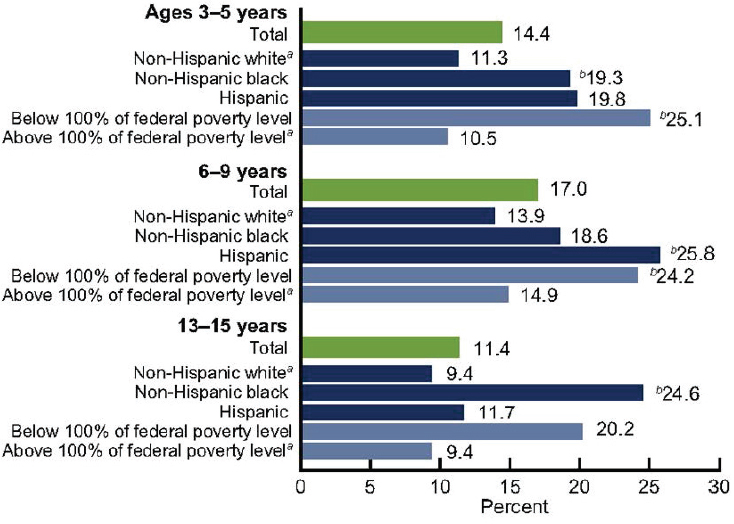

Figure 3-3 shows that dental caries begin early with 14 percent of children ages 3 to 5 having dental caries to some degree. In breaking that down, Valachovic said it becomes apparent that children who fall at or below 100 percent of the federal poverty level are at greatest risk and remain at high risk throughout childhood and early adolescence.

Valachovic explained that the adult population faces challenges with tooth retention. While those falling below the federal poverty level fare somewhat worse than their higher income counterparts (53 versus 42 percent), by the time they reach the 45 to 64 age category, only 29 percent retain all of their teeth, and those below the poverty level are at 15 percent.

Half of all Americans have some form of gum disease. Valachovic said this is significant when considering the oral systemic connection with

NOTE: Untreated dental caries varied by race and ethnicity and poverty level among children and adolescents. a Reference group. b P <0.95. SOURCES: Presented by Valachovic, October 6, 2016 (Dye et al., 2012. Data from CDC and NCHS, n.d.).

periodontal disease as a source of inflammation. It mediates through the rest of the body in the same way that any other kind of inflammation does.

Oral cancer is another problem, said Valachovic, especially with the increasing incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV), which kills as many people as melanoma and is now more common than leukemia.

In looking at dentistry’s responsiveness to society, there was an increase in the number of dental schools until 1980. After that, seven private dental schools closed between 1986 and the year 2000, resulting in a decrease in graduates from 6,300 in 1980 to 3,900 in 1990. This occurred in part because of a perception that dental caries had been eliminated. There was talk about creating generations of cavity-free kids so in that regard, there was a concept that dentistry had responded to society’s need. It became clear that

was not the case, so since 1999, 13 new dental schools have opened. All of them are in not-for-profit universities, bringing the total number to 66.

Looking at the diversity of the dental education, it is essentially an even percentage of male versus female enrollees, and since the 1980s inclusion of underrepresented minority populations has almost doubled. In conjunction with the Association of American Medical Colleges, the American Dental Education Association has set up a medical and dental summer enrichment program that has essentially doubled the likelihood that minority students will get accepted into medical or dental school.

Upon graduation, students have to be ready for private practice as licensed unsupervised practitioners. They are not required to go to a postgraduate year, with the exception of those practicing in New York and Delaware, which require it for licensure. Fifty percent of graduates go directly into private practice. One third go into a residency program of some kind. The remainder go into military, public health service, or a variety of other areas.

Value to Stakeholders

Valachovic then talked about generating value to actors in the systems as indicated in the guiding principles. Most educational interventions are not evaluated for their cost-effectiveness, benefit, or usefulness. However, accreditation does accomplish that in many ways. For dentistry, it is the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) that shows the benefit to students and residents who are the consumers of the education programs, as well as educational institutions, licensing and regulatory bodies, and ultimately the public. CODA, like most of the other accrediting agencies, mainly focuses on financial sustainability and stability.

Students do accrue significant debt for their education that, combined with their undergraduate expenses, totals on average $220,000. Despite this high debt level, dental graduates have essentially zero default on any of their loans. The graduates pay off their loans within roughly 7–10 years. That has not been an issue because there is basically no unemployment. If there is any issue with acquiring gainful employment, it is not because of the unavailability of jobs; there are a lot of opportunities for employment within dentistry.

Dentistry encourages lifelong learning through continuing education as well as an interconnectedness through interprofessional activities. Leadership within dentistry is driving collaborations within the academic health centers while also pushing greater interprofessional collaborative practices, to the extent possible. This is an effort to try and encourage dentists to think beyond employment in independent offices and to consider jobs that are more collaborative in all aspects of their work and education.

APPLYING A MODEL FOR FINANCING SPECIFIC INTERESTS IN HPE: SHIFTING FINANCIAL INCENTIVES TO MEET SOCIETY’S NEEDS

To delve more deeply into different aspects of the mismatches and other issues discussed throughout the sessions, workshop participants were divided into four breakout groups. Each group had two facilitators who designed the sessions and led discussions on how different funding mechanisms affect HPE financing, and how shifts in financial structures might better meet population needs. The groups met simultaneously for 1.5 hours.

When they returned, the group leaders were asked to provide examples from their small-group discussions that demonstrate one or more of the mismatches previously mentioned. Part of their presentation was to include levers that, if pulled, could shift HPE financing in a beneficial direction. The presenters were also asked to discuss drivers presented by Fraher at the beginning of the workshop, such as the economic market, that facilitate or impede better matching of supply and demand (see the levers and drives in Box 3-3). Then if possible, the leaders were to describe metrics that could be used to track progress in resolving mismatches identified in the presented example.

The four groups and the topics they covered are shown in Box 3-4. The following are the reports from each of the breakout group leaders to the participants of the workshop. These comments are a summary of the group discussions presented by the group leaders, and they should not be viewed as consensus.

Group 1: Who Should Fund Health Professional Education?

In their breakout group, Joanne Spetz and Mary Beth Bigley raised the provocative question of who should fund HPE; to what degree should financing HPE be a responsibility of the health system, the employers, the education system (which might be the public sector or might be private), or the individual (as in the dentistry model described in Chapter 3)? What is the balance? What are some innovations? What are some different ways of thinking about the problem?

Bigley offered two examples. The first involved exposing students to broader populations. Ideas for the example drew from veterinary medicine; Andrew Maccabe, representing the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, described how veterinary students are placed in animal shelters to give them exposure to different populations than what they would typically see in a general practice. The mismatch they are trying to resolve, she explained, involves closer linkages between education and the needs of the population. By training health professionals in different

environments, students are exposed to different communities in hopes of creating a greater understanding of a population’s needs that may differ from their own. This also exposes students to academic and community partnerships, and partnerships with employers. The incentives for offering community-engaged learning might come from financial incentives to employers. Then there are incentives to the students that choose to learn in nontraditional clinical settings. A stipend could help encourage students to move into those areas.

Bigley described the second example, which came from public health education. John Finnegan, ASPPH, talked about some initiatives that have happened in public health education. One is the requirement for accredited schools and programs to have field placements. The other piece involves tracking graduates of accredited schools and programs. Institutions want to know where their students are employed when they graduate, and if their work meets population needs. The accreditation mechanism is used as a lever to expose students to different populations in different environments.

The metrics she described would align with requests from accrediting bodies requiring academic–community partnerships. She thought the metric could involve the proportion of students learning from different populations in hopes that the 90 percent of students being trained and educated in traditional settings could be exposed to a full range of privileged and underserved populations.

Group 2: Identifying New Sources of Money to Pay for Health Professional Education

The second group, led by Edson Araujo and Zohray Talib, identified and discussed new sources of money for potentially paying for future HPE. They used a report from the United Nations High Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth as a backdrop to their discussions (WHO, 2016). An effort was made to explore nontraditional, new potential investors in HPE. Who might they be, how might they be engaged, and what would be a return on investment for new funders?

Araujo summarized the robust discussion stemming from his breakout group. He said that new funders for HPE include nontraditional government departments like ministries of labor, trade, and finance, as well as service providers, employers, and the private sector. Some new ideas from the private sector include social franchising. There were also suggestions about manufacturers, specifically pharmaceutical manufacturers, and some discussion of philanthropy. Philanthropy takes a broader approach that looks beyond the health sector and addresses such issues as job creation, economic development, lending, and microfinancing.

In terms of a mismatch, his group talked about productivity and its

link to value-based care and value-based education. Because many countries have issues with productivity in the health sector, that could be identified as a mismatch. Another mismatch is unemployment. Many countries have high unemployment despite shortages of health workers, particularly in some rural areas.

Araujo then discussed the policy levers that started with cross-sectorial dialogue. From the perspective of employment, jobs, and economic growth, there is a need to expand the conversation about HPE to include the education sector, the health sector, social protection, labor, and finance. The measured effects would similarly go beyond the health sector.

In terms of metrics, several members of his group discussed measuring the number of jobs created and the economic multiplier effect of having more jobs in health and the significance of that on the economy as a whole. This includes the effect of overproductivity in the economy and whether or not the health sector absorbs some of that overproduction from the other sectors. This needs to be better measured, he said. A long discussion ensued during their breakout group among the economists questioning whether the consumer price index that is used for the general economy applies to the health sector. The problem is that the productivity in health cannot be measured in the same way productivity in manufacturing is measured. For example, if the quantity or quality of health service increased in an area such as pain reduction, that is not captured in the consumer price index, although the change should be recorded. This would represent the downstream effects of HPE rather than education itself.

Araujo’s final point was that to measure the effects on employment of HPE beyond the health sector, there needs to be more information about the education and health workforce. This data would have to provide more information beyond simply the numbers of health professionals in each country; having more information on the other factors that influence career choices—such as anticipated wages, household income, and family circumstances—would further improve the understanding of the true effects of HPE on employment.

Group 3: Modernizing and Maximizing Government Support

In the third breakout group, Robert Smith and Wezile Chitha looked at state funding of HPE. Smith noted that while it sounds like a great proposition, there are real challenges and failures associated with relying on government support of education. However, there are also benefits that their group explored. One question Smith asked involved thinking about targeted funding. What might allow governments to maximize and deploy their health workforce in order to meet population needs? Smith quickly added that without some form of monitoring and evaluation, governments

would not know if their investments met their goals. Knowing where graduates practice and monitoring their work through well-kept sets of data could supply part of this answer.

The first mismatch Smith described involved the mental health needs of various populations, both internationally and within the United States. One program that addresses this mismatch is the Mental Health Facilitator (MHF) program. This program was described at a previous Forum workshop (IOM, 2015) and in the breakout group by Wendi Schweiger from the National Board for Certified Counselors. The MHF program is “designed to improve access to mental health care in a given community by educating and training community members from diverse backgrounds” (NBCC International, 2017). It is not meant to create a new mental health profession; rather, it is a train-the-trainer program that enables individuals to identify, support, and refer those in need of mental health services. Because this is a volunteer program, it is an inexpensive response to a community need. It is a service but not a full service; it supplements and complements traditional professional services and counseling.

Regarding metrics, Smith echoed Araujo’s comments on the need to go beyond simply counting totals of health workers. How might one count this mental health workforce, for instance? If it were as simple as saying there are a certain number of mental health workers in Malawi, that would be a start, but it would not go far enough. Most systems do not have ways of capturing and describing workforces, especially nontraditional ones.

His second example drew from a classic supply-and-demand mismatch within pharmacy. There is a misconception that there is an overabundance of pharmacists when in fact it was made clear by several breakout group participants that there is a continuing underemployment and shortage of pharmacists. The main metric used to measure the gap between supply and demand is the number of employment vacancies, which would be the measure of workforce shortages. Measuring oversupply of workers is much more challenging because the population needs are satisfied and it is very difficult to identify the underemployed or the unemployed persons owing to multiple confounding variables.

Group 4: Financial Justification for Socially Accountable Health Professional Education

The fourth group considered financial justification for socially accountable HPE. Led by Kathleen Klink and Erin Fraher, this group explored in greater depth financial issues as they relate to social accountability and the meaning of social accountability in the health education context. The group explored the educational process of health professionals with an eye toward meeting the needs of society and the population. In the discussions

among group members, special emphasis was placed on certain vulnerable populations such as the elderly, children, people with low incomes, or those living in geographically underserved areas.

They discussed potential health education modifications using currently available financing that would better ensure that education and its product, the workforce, addresses individual and population needs. In addition, the group considered what measurable information or data would be needed to document improved outcomes.

Klink summarized some key points about socially accountable HPE that were raised in her breakout group. First, by emphasizing health and wellness, a broad array of participants involved in health promotion need information and education, including caretakers in the home such as relatives who manage the health needs of their family members. Often, home caregivers need better understanding of technical aspects or about different types of medicines and other important issues related to their loved one’s care.

The second point is that leadership and institutional missions for addressing social determinates of health need to be aligned for any initiative to be successful. While the institutional mission is critical to introducing change, Klink emphasized that leadership is a key factor for implementing institutional missions.

Her third point is that services must be integrated across a community. Community in this context is defined as any group of individuals with health education needs. Assessments that determine need should stem from the community and be based on the community’s own identified needs and preferences. Similarly, and her fourth point, educational venues must be responsive to students’ and trainees’ needs for building competencies in the most appropriate learning environment for achieving that competency, whether within or outside of health care institutions. Qualified faculty, mentors, and role models are essential in meeting student and trainee needs. The role of faculty development, she said, is critical in addressing the current educational gap of preparing today’s workforce to attend to the social determinants of health in both individual and population health.

The fifth point she made was that public funding implies public service. Individuals or communities who receive public financial support through taxpayer dollars are accountable to their payers and have an obligation to society, again emphasizing the need for community involvement in planning and exercising interventions and educational activities.

Her sixth and final point was that socially accountable economic planning should be data driven and outcomes oriented. Establishing goals at the beginning of a program or project and creating data collection processes forms a strong foundation for the project and improves the potential to

demonstrate outcomes, both positive and negative—or even unintended findings.

Klink went on to describe the first mismatch between current and desired educational outcomes. When graduates do not meet the population needs, there is a disconnection between the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of graduates and the education they receive. In addressing the mismatch, Klink suggested providing experiences that appropriately prepare graduates for providing high-value care. High-value care is determined and assessed by the community members themselves. One example is the high narcotic prescription rate in some neighborhoods and the opportunity to lower narcotic use by treating pain syndromes using home-based care through nonmedication therapies. Educators may create learning environments and model roles for students and learners using complementary or alternative treatments. Another example is the creation of environments where health professional students learn about the lives of people who have become known as hot spotters—patients who are 20 percent of the population that use 80 percent of the health care dollars (Gawande, 2011). In this way, students learn from those they serve in the settings that will allow understanding of patients’ circumstances.

Metrics for measuring the return on investment may involve clinical and other outcomes. These might include measurably improved patient health such as decreased hospitalizations, cost savings, and fewer emergency room visits. Demonstrating a link between student training environments and graduates’ practice choices could be another measure of return on investment for addressing this mismatch.

The second mismatch Klink described involved end-of-life care. Creating health training and learning environments that support nonhospitalbased end-of-life care and care for those considered frail could help to meet the goal of keeping frail and terminally ill people out of the hospital, a frequently cited preference of patients at the end of life. This involves a shift from expensive, fee-for-service care to team-based, supportive care in the home, through such mechanisms as the currently underused Medicare hospice benefit.

Klink said a metric for measuring steps toward addressing this mismatch would be based on comparing annual expenses of individuals prior to and after an intervention. For populations, comparison could be between a group that received the intervention with one that did not, in order to estimate total savings. Another way to look at the metric would be to contrast the number or percentage of patients who died outside the hospital compared to previous years. She said that the intent is not to prevent death but rather to ameliorate pain and discomfort, to accede to patients’ desires to remain in their homes with their families, and to avoid the dispropor-

tionately high expenses associated with hospital-provided end-of-life care (Stanford University SOM, 2017).

REFERENCES

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics). n.d. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data, 2009-2010. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/nhanes09_10.aspx (accessed January 17, 2017).

Dye, B. A., X. Li, and G. Thornton-Evans. 2012. Oral health disparities as determined by selected Healthy People 2020 oral health objectives for the United States, 2009–2010. National Center for Health Statistics data brief, No. 104. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Fraher, E. 2016. A model for financing health professional education. Presented at the workshop: Future Financing of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, October 6.

Gawande, A. 2011. The hot spotters: Can we lower medical costs by giving the neediest patients better care? The New Yorker, January 24, 40-51.

Hall, D. 2011. Debate: Innovative teaching to enhance critical thinking and communication skills in healthcare professionals. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice 9(3):Article 7.

HEE (Health Education England). 2017 (unpublished). General practitioner forecast supply. Leeds, England: HEE. Unpublished dataset, cited with permission.

HSCIC (Health and Social Care Information Centre). 2014. NHS Hospital and Community Health Service (HCHS) workforce statistics in England, summary of staff in the NHS—2003–2013, overview. Leeds, England: HSCIC. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB13724 (accessed March 3, 2017).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2015. Building health workforce capacity through community-based health professional education: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NBCC International. 2017. Mental health facilitator (MHF). http://www.nbccinternational.org/What_we_do/MHF (accessed January 17, 2017).

Smith, R. 2016. Clinical pharmacists in general practice. Presented at the workshop: Future Financing of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, October 6.

Stanford University SOM (School of Medicine). 2017. Palliative care. https://palliative.stanford.edu (accessed March 3, 2017).

WHO (World Health Organization). 1978. Declaration of Alma-Ata International Conference on Primary Health Care. September 6-12, 1978. Alma-Ata, USSR: WHO.

WHO. 2016. Working for health and growth: Investing in the health workforce. Report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

This page intentionally left blank.