4

Reflections and Potential Next Steps for Building a Model

REFLECTIONS ON THE WORKSHOP DISCUSSIONS

Charles Ok Pannenborg, former World Bank

Pannenborg, former World Bank Chief Health Advisor/Director and Chief Health Scientist, reflected on the discussions he heard throughout the workshop. He came up with 25 windows through which health professional education (HPE) could be viewed from a financial perspective. Pannenborg highlighted certain windows in his talk starting with what he termed tunnel

vision. It is natural for everyone to have some level of tunnel vision, he said, but despite the accomplishments of the educators and health professionals in the room, he found the conversations surprisingly inward looking to their own professions or their established world view. Additionally, there was an imbalance between the expression of what is known about one’s own profession and the lack of curiosity about other professions and other sectors. For example, he applauded the development of the model, but the discussions centered primarily around the labor market. He heard very little about financing. The discussions were about supply, mismatches, demands, but not much about financing.

Seeking New Financial Partnerships

Within his second window, Pannenborg urged the workshop participants to explore relationships with other academic departments that are not part of traditional health fields. This might include hybrid fields like medical physics, health economics, or engineers in transportation. In terms of future financial flows, investors in accelerators in physics are fundamentally different from investors in health professional schools, so teaming with the physics department may improve prospects for funding.

The next window he described involved the private sector. While mentioned previously by Edson Araujo, Pannenborg believes the private sector will grow even more dramatically than what Araujo predicted. The example he cited is the Laureate Education Corporation. Known formally as Laureate International Universities, Laureate is a public benefit corporation made up of campus-based and online degree-granting higher education programs spanning 88 institutions in 28 countries around the world (Laureate Education, Inc., 2016). With more than 1 million students, this company is growing almost exponentially. Pannenborg anticipates that public funding will be reduced while private funding will expand in terms of financing, and that will include HPE. This will have a range of implications for quality and accreditation.

Pannenborg used his native country, the Netherlands, to make a distinction between the private and public sector in terms of ownership and financing. While the corporate ownership of the academic medical centers, medical schools, and university hospitals is a complicated mix of both public and private legal entities, the defining characteristic of all of them is that 98 percent of their funding—so far—does come from public money. Similarly, appointments and contracts of health professionals’ teaching and research faculty increasingly are a public and private combination in terms of their origins.

This led to Pannenborg’s comment about public money. There is a general impression that governments will always provide the needed support for health professionals to be trained. However, the recent estimate reported at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) annual meeting is that the world is $152 trillion in debt (IMF, 2016). At 200 percent of the global economy, this means governments will essentially have no money, so the assumption that governments will be able to finance all the additional health professionals that were highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO) as necessary—at least 14 million additional health workers needed by 2030—is largely an illusion. How one looks at the constraints around public financing will no doubt be colored by ideology. Pannenborg pointed out that very few of the discussions at the workshop or other venues have been open about the reality of HPE funding, and he encouraged the audience to open the dialogue on this critical topic. However, history shows that open dialogue about such issues may be difficult. Pannenborg reminded the audience about an attempt about 35 years ago to advise the United States on how many physicians it needed to serve the population (Salsberg and Forte, 2002). The Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee (GMENAC) issued estimates in 1980 that, for seemingly political reasons, were never used and never again attempted by the government.

In the wake of the GMENAC failure, the WHO abolished its health manpower department. It took 20 years to build it again, which was not unlike governments around the world. Many ministries of health abolished their human resources for health (HRH) departments that also took 20 years to return. Pannenborg emphasized the importance of ideology, to recognize it, and be open about it so mistakes of the past are not repeated in the future. Pannenborg said this could be included in the mandate of this group—to open dialogue on difficult and sometime contentious issues in order to set a nation and its health professionals on the right track.

Pannenborg’s next window critiqued the workshop discussions, pointing out a lack of robust dialogue around engaging ministries of finance. To safeguard at least some of the public financing for HPE in the future, he said it is important to engage directly with the individuals in the ministry of finance. Their thinking is entirely different from health or agriculture professionals. To connect with them, Pannenborg said health professionals and their educators will need to build a community within the health professions and education who can act as translators in working with ministries of finance. Building strong relationships within the ministry is particularly advantageous when additional resources are needed within HPE. At those times, the connections and communication links are already in place.

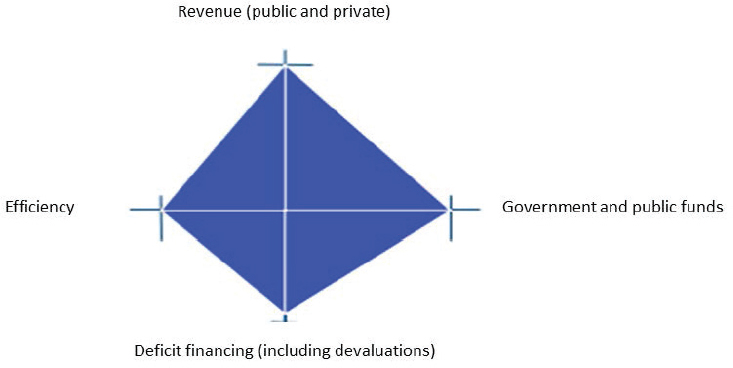

Figure 4-1 was developed from Peter Heller’s work at the IMF (Heller,

NOTES: This is an adaptation of an original work by the World Bank. Responsibility for the views and opinions expressed in the adaptation rests solely with the author of the adaptation and are not endorsed by any member institution of the World Bank Group.

SOURCES: Presented by Pannenborg, October 7, 2016 (adapted from Okwero et al., 2010).

2006). It shows the fiscal space diamond1 that is generally used as a framework to assess fiscal space of national governments; however, Pannenborg adapted it to apply to the workshop topic. Where on the line would a minister of finance place his or her emphasis, asked Pannenborg? She would likely immediately move to the left and refuse deficit financing or more revenue through public funds until HPE addressed the inefficiencies in health and medical schools and teaching hospitals, which in the eyes of many a finance minister, would often be described as a managerial inefficiency and a money wasting disaster.

Exploring New Funding Sources

Another window Pannenborg was eager to share involved the distinction between funds available for research and funds available for teaching, education, and training. Research can be worth billions of dollars, but it is

___________________

1 Okwero and colleagues state: “Fiscal space can be graphically represented by a fiscal space ‘diamond,’ which reflects the four sources of fiscal space. The axes of the diamond reflect the four areas of budgetary revenue, and the area of the diamond reflects the total available fiscal space, with larger areas suggesting more fiscal space” (Okwero et al., 2010).

often seen as separate from education. In countries in Africa and Asia, there are now large scientific institutions that have no academic affiliation. Too many of those brilliant researchers are not teaching or training anyone, he said. From a financing point of view, getting money through research could be a much-needed source of funding.

He also noted that like investments in Boeing, AirBus, or Bombardier Transportation, HPE is a long-term capital product. It will not produce quarterly returns in the way that financiers are accustomed to. This needs to be considered when approaching those sorts of investors.

Pannenborg then built on one of his earlier comments about the assumption that money for HPE will always be available from the public sector. He discouraged this thinking and instead urged the audience to look for specific players in the investment world. Unlike the generic list of actors defined in the model (e.g., government financing, the private sector, and public insurance companies), Pannenborg wanted the biggest financial actors listed. In health, this would be the insurance companies such as Allianz Global, the Investment Department of Allianz, AXA, and Prudential. These groups are actually looking for investment opportunities, he said. The interest rates are so low that even pension funds have to expand into nontraditional sectors because they do not have a return anymore. This is an area that could hold promise for funding HPE in the future.

In considering other discussions throughout the workshop, Pannenborg brought up the tendency of senior managers to have one-off tactical and short-term thinking. For example, they realize they need more veterinarians or medical doctors so they build a new school or maybe another teaching hospital, but there is no comprehensive long-term investment strategy for a country’s overall HPE requirements and returns. Such a strategy might also include bonds. Vanderbilt University Medical Center issued a bond of $530 million, which provides a sense of the order of magnitude being discussed. It was underwritten by the public sector, but is going increasingly into the private sector.

Reaching Across Borders and Sectors

There is also a global option for training specialties. Sanofi, a French multinational pharmaceutical company, identified a shortage of pharmacological scientists, but educating and training this specialty in France would be an expensive proposition. It instead opted to educate and train the needed scientists in Algeria at less than half the price. Sanofi is now financing a significant percentage of the department of pharmacology at the University of Algiers. Pannenborg does recognize that overseas training poses questions in terms of academic independence, but from a purely financial perspective, the University of Algiers benefited tremendously from

this model. Similarly, Pannenborg reminded the workshop participants that each of the 10 largest globalized banks in the world (including those in China) has a department of health sector investment that needs to be part of the thinking moving forward.

Another window he identified looked at regulations versus monopolies. This is essentially a labor market where the in-flow is regulated because the power has been delegated by governments, by law, to the health professions. It can almost be considered systemically corrupt because the profession controls its own economics. By self-governing how many people can enter their highly sought-after profession, the professionals themselves keep their own incomes high. It is very simplistic. In terms of the labor market, it means opening the market in that profession; if that is not done, making changes in curricula and data collection on workforce shortages will not change the situation.

Engaging the education sector in health is another important element. Often those in ministries or departments of education know little about health and are therefore excluded from the discussions. But to look at the full spectrum of financing HPE, these ministries need to be part of the conversation, said Pannenborg. Previously, when the World Bank made investments in universities around the world, they funded everything except the medical school; this was because the medical school, together with the teaching hospital, often is the largest expense of the university. The financing and power structure generally is too complicated to try to figure out how to fund it, so it is simply excluded. Fortunately and encouragingly, the World Bank now proactively invests in the development of the health professions around the world both from an education and from a health investment perspective, recognizing that the health and biomedical sciences in their widest sense are crucial for the economic and social development of a country and can contribute importantly to economic growth. In some countries, teaching hospitals have more power than the medical schools, which is the opposite in many other countries. Investors do not like that level of insecurity—they prefer specificity and knowing explicitly who has power over the money, the expenses, and the future investments. They feel similarly about profit margins; investors want to work with people who are open about their current and projected finances.

Pannenborg again encouraged the audience to consider the private sector. Adecco and Randstad are the largest purely private-sector staffing and manpower companies running health professionals. They are much larger than any medical school, and larger than any health sector in the states or small countries. Both of these companies make billions of dollars in profit each year. Engaging these companies could be advantageous, and ignoring them would not be helpful.

He went back to the health insurance industry to make his next point

about consolidation. Health insurance companies around the world have assets worth hundreds of billions of dollars. This is not surprising given the degree of consolidation they have undergone. Learning from this industry, Pannenborg predicts that in the next 30 years, many countries will see a similar shift of health professional schools with enormous consolidation. He said from a financial perspective, this is desired—although it brings with it challenges.

In his final slide, Pannenborg admitted that in many countries, a lack of money makes close ties with the private sector a somewhat unrealistic option. A more realistic possibility is public–private partnership. These relationships could form between governments and private-sector players as well as a profession itself. His final message was to be inclusive. This means engaging financial and accounting experts to team with health professionals and others who understand the returns on investments in the area of interest. They should all be part of the decision-making process.

REFLECTIONS ON BUILDING A MODEL

Malcolm Cox, Forum Co-Chair

In reviewing the comments made throughout the workshop, Malcolm Cox, University of Pennsylvania and former chief academic affiliations officer for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, isolated some key issues. He began by emphasizing the importance of models for several reasons. They provide a framework that reminds the user about categories of issues that, in the case of this workshop, include an inventory of drivers and levers for financing HPE. Models also help identify potential or real problems that may not be easily recognized or evident. Using the model to identify synergy or mismatches between various components can be a way of identifying levers and testing potential solutions.

Cox pointed out that models are not static. They need to be refined as new variables are identified and others are deemed no longer pertinent—both within and exterior to the model. In this regard, models go through different iterations, but having a starting framework is very useful. What will ultimately determine the model’s usefulness is its flexibility and predictability. It should be flexible enough to apply to different local, national, and international contexts, and it should evolve toward a predictive model for testing hypotheses.

In looking at the demand side of the model, Cox encouraged the audience to rethink the term societal needs. Are these real or perceived needs, and who will be the arbiter of those needs? Health professionals may think they should determine what society needs, but Cox believes it should be the public. If that is so, who is the spokesperson for the public and how is that

relationship managed? Theoretically, local or national policy makers could speak for society since they are the conduit by which public needs are expressed and modulated, although they are not always viewed positively by the public. Educating the public to fill information gaps could enable them to be their own spokespersons. This is where Cox sees the role of health professionals in filling the community-level information gap.

Cox then redirected his remarks toward addressing social and economic returns on investments. How are they defined? Once defined, how are they quantified in terms of outcome metrics and analyses? While Cox admits that metrics are critical to determine outcomes, he cautions against becoming subsumed by them. Simple metrics, such as the number and distribution of health workers by workforce type, is a measurement that is frequently collected. This could be used even though it is not ideal, he said. His point is to avoid any excuses around uncertainties that create barriers to undertaking measurements because of a perceived notion that only complex metrics will yield valuable information.

The supply side, said Cox, is particularly applicable to health professionals. He drew ideas from the presentations described in Chapter 3 that had made a significant impact. For example, Walter Sisulu University, which is not far from where Cox grew up in South Africa, has unique admissions criteria. Their admissions criteria preferentially select students from local, rural communities who, statistics show, are more likely to go back to their own community to practice following graduation than those coming from more affluent and urban environments. Somewhat similar to this example is the use of curricula to place learners in community settings. Educating students entirely in hospital settings does not expose them to the full array of issues confronted by community members who may be negatively affected by social factors not directly related to health, such as transportation, mobility, or safety concerns.

Another supply side lever is debt relief. Debt and its avoidance are powerful incentives for many students making career and education decisions. Incentives are not the only levers, but they are important ones that can push for small changes with potentially major impacts. Cox spoke of the importance of incrementalism. Policy changes rarely come from radical alterations. More typically, change comes from small, incremental steps that Cox believes can emanate from the health professionals and the educators in this audience. Many of these same participants recently attended a Forum workshop on accreditation that Cox identified as yet another key incentive or lever.

Cox then offered some suggestions for how the Forum members and other workshop participants could help implement the ideas presented at the workshop. First, individuals could work within their professions or professional associations or institutions to form strategic partnerships

across professions and between education and delivery systems. Educational reforms and clinical or system redesigners rarely talk to one another. He challenged participants to spend time thinking about what can be done to bring these groups together at their own institutions, which would be a major step toward resolving mismatches between education and practice.

Second, members of the Forum and others could set up community partnerships. These could link the individual’s institution or professional association with community members in simple ways such as making community members active contributors of advisory boards.

The third and final suggestion to the workshop participants was to become institutional change agents. By getting buy-in from leaders who can help promote and identify other leaders, members of the Forum can expand their sphere of influence for affecting levers and drivers for equitable financing of HPE.

MOVING FORWARD WITH BUILDING A MODEL

Erin Fraher, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

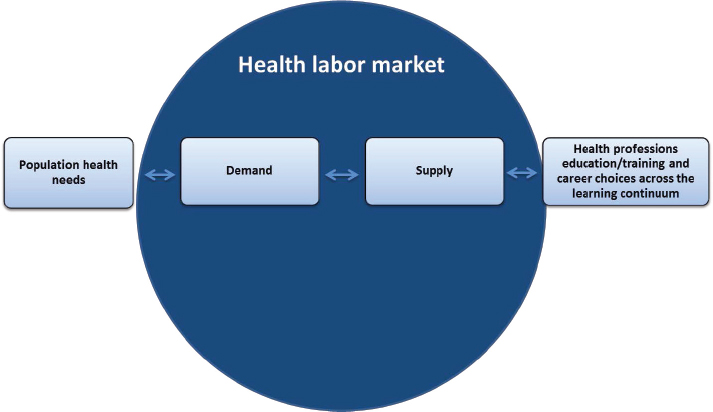

Erin Fraher led a final discussion on the model. Her remarks were drawn from the audience feedback collected throughout the course of the workshop. There are population health needs on the one hand, said Fraher, and the health professions’ education and training programs on the other. In between the two is the labor market mediating whether those two sides meet. One issue that was pointed out by numerous individuals is the lack of a time element in the model.

Timescale

According to Fraher, any sort of policy change in health professions financing is going to be incremental. There will be gradual change over the longer term. This mitigates the risk of completely changing the system too fast, which could result in a loss of capacity or a more drastic change than was intended. The timescale for implementing change in HPE financing is shown in Box 4-1.

Box 4-1 shows three levels (short-, medium-, and long-term) for rebuilding a system involving health, education, and finance. Short-term change is considered less than 10 years, which can also be viewed as having a decade to address short-term mismatches. Robert Smith’s presentation on pharmacy as a solution to the undersupply of general practitioners is a good example of this. The medium-term solution (a 10- to 15-year timespan) would have been to train more general practitioners to balance the mismatch between population needs and the supply of health workers. Instead,

Smith and his colleagues elected to retool the existing workforce by using a dynamic, short-term solution to the mismatch.

Another option might have been to fundamentally change the demand side. This would involve adjusting a payment model that would require moving to a value-based system and a longer-term timescale, such as in the United States. It could be a medium- or long-term timeframe of more than 15 years into the future.

Fraher then shifted her comments to another element of time. The model has to be dynamic, flexible, and contextualized, she said. Once the supply is changed, this will likely influence demand, which is part of a feedback loop. There are other potential feedback loops the model will have to respond to. The model will need to be dynamic and flexible in response to local or individual situations as they arise.

Marilyn Chow from Kaiser Permanente commented on the timeframe issue. She compared the timeframe for this model to the technology industry. Fifteen years would seem like an eternity for them; how might the Forum members think in shorter timeframes? What are the barriers to rebuilding a quicker system, to shortening time frames, and to creating more responsive markets? If it is the length of the education or how long it takes to prepare someone, then how might that time be shortened and what would that look like?

Fraher applauded Chow for challenging her and others to think in briefer time periods. Whether the problem emanates from the supply side or the demand side, thinking through how fast to move will adjust the options for addressing the problem. For example, retooling the workforce is a faster solution than creating new workers, so the model can be a way of helping think through policy options.

Bjorg Palsdottir, representing Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet), agreed that rapid change is important, but that real political

shifts will probably take a long time. Fraher was intrigued with the notion and drew on her recent 2-month sabbatical in New Zealand to reinforce the point raised by Palsdottir. The New Zealand treasury is taking a social investment approach to health professions education. It recognizes the value of investing and intervening early in the life course process to obtain more positive educational results later. It is very unusual for a government to take a political risk in the short-term to gain long-term outcomes. In this case, New Zealand opted for a very large short-term investment for very long-term social benefits that reduce costs in an even longer term.

While agreeing with the conversation, Joanne Spetz, University of California, San Francisco, and moderator of the financing examples session, reminded participants that Figure 2-8 is not a predictive model. It is intended to be a model or a framework for thinking about where workforce challenges may occur and what levers are available to address them. Some levers will have impacts in the short term and some in 5 years or 10 years, but depending on the region, it may be possible to demonstrate outcomes in just 2 years. Much of this depends on the context in which the workforce challenge is occurring. Because so much is contextual, Spetz encouraged the group to understand what the model can offer and to be aware that like any model, it can at times also produce misleading information.

This discussion on timescales drew varied comments from individuals, including

- short-term victories can be lost without long-term monitoring;

- sustained, long-term change requires determination;

- the time for learning goes well beyond foundational education into workforce learning;

- some things, like regulation, cannot change within a short time span of under 5 years; and

- timescale as a unit of analysis depends on the country or geographical region of interest.

Guiding Principles Review

The next area Fraher reviewed was the guiding principles. In reflecting upon previous discussions about the principles noted in Box 2-1 of this report, Fraher commented that the language responsive to society was too passive, and updated it to accountable to society. She also added flexible, as seen in Box 4-2, to convey a need to adapt to new situations especially when systems are in a state of flux.

The term diverse was added in an attempt to show a desire for ethnic, racial, linguistic, and other forms of diversity within HPE, said Fraher. A guiding principle that overlaps with the previous timescale discussion is

sustainable. This was included to encourage educators, researchers, and funders to think beyond the grant-funding period and to consider what would make a health professions financing policy sustainable. The last principle is accessibility. This includes accessibility to health care services but also to health careers. Kathy McGuinn from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing thought back to conversations she had at the workshop and proposed adding interprofessional to the list of guiding principles. It could be linked with interconnected, because the latter term mostly represents connections between academia and practice. Fraher agreed before opening the floor to others for their individual reflections on the model’s guiding principles, which included the following remarks:

- Context is important: For example, rural communities are different from society at large, so being accountable to society and communities would be more equitable.

- Consider the step before the model: There needs to be a pipeline of eligible students that recognizes the lifelong value of education for building a qualified workforce.

- There are two categories of guiding principles: One includes the fundamental foundational principles, like accountability to society,

- Ensure a global relevance: Do these terms used in the guiding principles have the same relevance with different audiences in different countries?

- Finance is a narrow piece of the bigger, broader picture: The model is really about future economics of HPE and not as much about financing.

and the other involves operational principles, like being nimble and flexible.

Actors and Stakeholders

When reviewing the list of actors, Fraher included current and future learners as shown in Box 4-3. There was an initial discussion about including employers on the list that morphed into thinking about the wider business community, she said. Many businesses offer health insurance to their employees and therefore have a stake in ensuring the quality of health education outputs.

Fraher then remarked that clinical systems were raised previously as another category of actor, but she wondered whether clinical systems should be a subset of health systems. This question led to numerous remarks from

individuals about the right level of disaggregation versus aggregation, and whether the list was too long. One participant pointed out that clinical systems are actually part of the education system. In fact, clinical is the link between education and practice in the health professions.

Similar observations were made over dividing or combining payers. Ultimately, she disaggregated them to include government as well as taxpayers and for-profits, such as insurers.

Nontraditional health professions educators working in the community is another group Fraher felt should be included in the list. Do health systems adequately describe public health and community-based services? Then she reminded the audience of previous remarks asking who the spokesperson for the community would be given the vast number of organizations in a community.

As the conversation continued, Fraher was reminded of other discussions at the workshop about commercial lenders as actors, as well as philanthropists, policy makers, and other political players. She then added community-based financiers and local cooperatives globally to the list before commenting that the media is another potential actor in terms of facilitating change. The labor unions represent a unique segment of the population, said Fraher, so that too was added to the list.

Warren Newton responded to a question raised about the term actor for describing the stakeholders. The term was taken from a 2013 WHO Policy Brief on Financing Education of Health Professionals (WHO, 2013). However, since some individuals expressed a preference for using stakeholders, he added it to the model. Pannenborg offered his suggestion that investors and lenders be added to the list of actors and stakeholders. He suggested not adding commercial lenders because in the financial world, the word commercial has a very particular meaning.

Workshop Adjournment

In her closing comments, Fraher presented some additional updates she incorporated into her model (see Figure 4-2).

The first was in response to Pannenborg’s comment that the title is not entirely accurate, since the focus of the model was more about economics than financing. Another modification to the title was the addition of the word value. Cox pointed out that in health care delivery, value-based delivery includes both quality and cost. Applying this thinking to education, value-based education would incorporate into the model a cost component as well as the benefits to society and how efficiently or inefficiently funds are being used. He also suggested some acknowledgment that education and its financing runs across the educational continuum from foundational education through graduate education to life-long learning as a fully formed

SOURCE: Presented by Fraher, October 7, 2016, adapted from Figure 2-8.

health professional; in his opinion, this continuum should be added as an element of the model.

With those final comments and updates to their model, Fraher and Newton thanked the participants and the workshop planning committee and adjourned the workshop.

REFERENCES

Fraher, E. 2016. An updated value model for financial economics of health professional education. Presented at the workshop: Future Financing of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, October 7.

Heller, P. S. 2006. The prospects of creating “fiscal space” for the health sector. Health Policy and Planning 21(2):75-79.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2016. Debt: Use it wisely. Press conference opening remarks. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2016/10/06/AM16-SP100516-Debt-Use-It-Wisely-Opening-Remarks (accessed January 19, 2017).

Laureate Education, Inc. 2016. Laureate international universities: A leading international network of quality, innovative institutions of higher education. http://www.laureate.net/AboutLaureate (accessed January 19, 2017).

Okwero, P., A. Tandon, S. Sparkes, J. McLaughlin, and J. G. Hoogeveen. 2010. Fiscal space for health in Uganda. World Bank working paper no. 186. Africa Human Development Series. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5949 (accessed March 9, 2017).

Pannenborg, O. 2016. Linking a model for financing HPE to global movements and individual initiatives. Presented at the workshop: Future Financing of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, October 7.

Salsberg, E. S., and G. J. Forte. 2002. Trends in the physician workforce, 1980-2000. Health Affairs (Millwood) 21(5):165-173.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2013. Transforming and scaling up health professionals’ education and training: World Health Organization guidelines 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.