1

Introduction

While much progress has been made over the last decade toward achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs),1 the number and complexity of global health challenges has persisted. Growing forces for globalization have increased the interconnectedness of the world and the interdependency among countries, economies, and cultures. Monumental growth in international travel and trade has brought improved access to goods and services for many, but such growth carries with it an ongoing and ever-present global threat of zoonotic spillover and infectious disease outbreaks, including in recent years avian influenza, Ebola, Zika, and chikungunya. This threat intensifies each year in the face of diminished budgets, especially when considering the corresponding increase in urbanization and population density worldwide. Simultaneously, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) have continued to grow in prevalence and impact on economies, threatening societal gains in life expectancy and quality (WEF, 2017). Many countries now face a rising burden of NCDs such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, while still trying to eliminate such diseases as tuberculosis (TB), malaria, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Unfortunately, many health care systems in these countries are not designed to care for noncommunicable

___________________

1 The Millennium Development Goals are “The world’s time-bound and quantified targets for addressing extreme poverty in its many dimensions-income poverty, hunger, disease, lack of adequate shelter, and exclusion-while promoting gender equality, education, and environmental sustainability. They are also basic human rights-the rights of each person on the planet to health, education, shelter, and security” (Millennium Project, 2006).

TABLE 1-1 U.S. Program Successes for Global Health

| Program | Successes in the 21st Century |

|---|---|

| The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) |

|

| President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) |

|

| Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) |

|

| U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) Acting on the Call: Ending Preventable Child and Maternal Deaths |

|

NOTE: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; WHO = World Health Organization.

diseases and current infrastructure lacks a focus on integrated care, a properly trained workforce, and effective population-level policies—elements that can significantly improve these serious health burdens.

Over the last few decades, the United States has significantly contributed to global health successes in key priority areas, such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, research and development for health security threats, and saving the lives of mothers and children, as illustrated in Table 1-1. Even more recent commitment is evident through the creation and dedication of the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) and efforts to combat antimicro-

bial resistance (AMR) at the national and international levels. While the world’s attention is easily captured by infectious disease events like Ebola or Zika, it is also important to address the burdens of chronic diseases plaguing populations and adversely affecting their economic growth. Identifying cross-cutting solutions to address all facets of health is necessary for sustainable progress. The gains bought with billions of U.S. dollars are poised to be sustained and grown, or phased down and lost. A loss of focus in key priority areas—responding to disease outbreaks; sustaining gains in HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria; ignoring the health of women and children; or disregarding the growing imperative of the NCD burden—would be a tremendous opportunity loss for the United States and humanity.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT FOR THIS STUDY

For decades, the United States has been involved in foreign aid and global health in some capacity. Various efforts and programs were expanded following the creation of The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2003 and the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) in 2005. Since the establishment of these two initiatives, along with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in the early part of the 21st century, the field of global health has seen tremendous growth and has evolved through a proliferation of nonprofit and private foundations, with a keen interest in and commitment to improving the health of vulnerable populations around the world. While these changes were occurring over the past two decades, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine conducted two consensus studies on this topic, charged with advising future government leadership on areas of prioritization within the growing field of global health.

Past Institute of Medicine Reports on Global Health

Twenty years ago, the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Board on International Health was commissioned to produce the first report directly addressing the United States’ interest in and commitment to improving human health on a global scale. The report America’s Vital Interest in Global Health: Protecting Our People, Enhancing Our Economy, and Advancing Our International Interests (1997) construed global health as “health problems, issues, and concerns that transcend national boundaries, and may best be addressed by cooperative actions” (IOM, 1997, p. 2). Twelve years later, an independent committee was formed by the IOM Board on Global Health to prepare a new report, The U.S. Commitment to Global Health: Recommendations for the New Administration (2009), to advise the incoming Obama administration. The 2009 committee was tasked with assessing

U.S. efforts in global health and making recommendations about future priorities and opportunities to improve health worldwide, while also protecting and promoting U.S. interests. Due to the breadth of the statement of task and the time constraints of the study, the committee’s approach was to focus on the directions needed for the future. The committee was not able to conduct an in-depth review of these two previous reports and the progress made since their release. However, several themes from those reports emerged in initial discussions to inform the committee’s deliberations, with some outlined in this chapter (see Appendix A for more detail on the previous IOM reports’ recommendations and the advancements in global health since their release).

The IOM’s 1997 report America’s Vital Interest in Global Health showed that, even 20 years ago, there was an appreciation for the interconnectedness of the world and the interdependency of the United States with other countries. As the report underscored, “the direct interests of the American people are best served when the United States acts decisively to promote health around the world” (IOM, 1997, p. 2). Also included in that report were calls for better structuring of market incentives for the needed development of critical medical products, an area that the global health community still struggles with today. Since then, however, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response established the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) through the 2006 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act,2 which incentivizes the private sector to collaborate, develop, and ensure surge capacity for drug and vaccine manufacturing through cost-sharing mechanisms and partnerships with the U.S. government. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) priority review voucher program, established in 2007 (Ridley, n.d.), also spurs development by allowing for expedited FDA review of certain types of new drugs (e.g., products to treat Ebola became eligible in 2014). Additionally, with the recent launch of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation in January 2017, it is clear this need for drug and vaccine development in an uncertain market is still a priority and will require international public- and private-sector collaboration.

The 2009 IOM report The U.S. Commitment to Global Health followed an explosion of global health programs and an increase in total global health funding between 2000 and 2008. To generate and share knowledge, as well as build capacity, the report called on the U.S. research sector to collaborate with global partners, establish information sharing networks, and support academia and health systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) through country-led workforce development and the creation of national health plans (IOM, 2009). Progress in health research collabora-

___________________

2 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, Public Law 109-417, Sec. 401.

tion since 2009 includes the Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research (PEER) (2011), a competitive program that awards scientists from LMICs (and partners them with U.S. government–funded researchers) to support research and capacity building. Additionally, the formation of the medical education partnership initiative and nursing education partnership initiative, developed through the PEPFAR program to address the severe workforce shortage of health workers in high-burden HIV/AIDS countries, has enhanced workforce capacity (see Chapter 4).

Perhaps the most notable recommendation of the 2009 report was to improve coordination across the U.S. government by creating a White House Interagency Committee on Global Health, chaired by a senior official designated by the president, to be tasked with leading, planning, prioritizing, and coordinating the budget for major U.S. government global health programs and activities. This concept was implemented through the launch of the Global Health Initiative (GHI) in 2009 by President Obama. However, with an initiative spanning so many agencies and health areas, its success depended on strong authority and budget given to the GHI organizers. Unfortunately, it received neither, and by 2012, the committee found that GHI had little more than a Web presence coordinating priority area global health programs. Though full U.S. government interagency coordination and cooperation in global health was not realized in the past 10 years, many smaller-scale coordination efforts have been successful, such as Feed the Future, PEPFAR, PMI, and most recently the GHSA. The committee feels that coordinating efforts within a manageable scope with dedicated funding, leadership, and accountability is feasible and should be a key consideration as the new administration looks to the future to shape U.S. global health programs.

STUDY CHARGE, APPROACH, AND SCOPE

In follow-up to the 1997 and 2009 IOM reports on global health priorities, a broad array of stakeholders sponsored the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to conduct a similar consensus study to review changes in the global health landscape over the last 10 years and assess future priorities. In addition, this expert committee was tasked with making recommendations on how to improve responsiveness, coordination, and efficiency within the U.S. government and across the global health field. Finally, the committee was charged with guiding the new administration, as well as other funders and global health actors, in setting future priorities and mobilizing resources (see Box 1-1 for the full statement of task). The sponsors of this study included the Merck Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), PEPFAR, The Rockefeller Foundation, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID),

the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, with additional support provided by BD (Becton, Dickinson and Company) and Medtronic, demonstrating the diversity of entities that understand the importance of global health issues and trends. The recommendations that the committee has developed are far reaching and applicable to multiple agencies and stakeholders, including nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), private-sector companies, and national ministries of health in other countries. However, as the U.S. government maintains its role as a leader in global health, the committee directs many of these recommendations to the new administration and federal agency leaders and hopes the U.S. government will continue to lead through action, and in partnership and collaboration with the numerous public and private stakeholders on the global health stage.

Approach

The 14-member committee, appointed in August 2016, deliberated over the course of 5 months and four in-person meetings, in addition to working electronically and via phone, to compile this report and its 14 recommendations. Two of the meetings included information-gathering sessions from sponsor representatives and additional subject area content experts. The agendas from these two meetings can be found in Appendix C. To better understand the challenges and successes of programs implemented in other countries, the committee also distributed an information-gathering request via SurveyGizmo to 12 USAID health directors and 40 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) country directors, asking respondents to give qualitative responses to questions regarding their work with U.S. global health programs (see Box 1-2). Forty-eight responses were received, and responses can be accessed via this project’s Public Access

File.3 Furthermore, the committee conducted an extensive literature review on relevant topics.

Scope and Limitations

Global health challenges span a broad range of health conditions, risk factors, and policy issues. The wide range of health conditions that afflict the global population was investigated in the 2015 Global Burden of Disease Study, which found that 315 conditions contributed to the majority of global disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)4 in 2015 (Kassebaum et al., 2016). The same study identified 79 behavioral, environmental, occupational, and metabolic risk factors to health that can be addressed (Forouzanfar et al., 2016). Beyond specific disease and risk factors there is increasing recognition of the influence of climate change and the environment on global health. While these challenges are all important, the committee has decided to focus this report on areas it believes the United States can have the most immediate and substantial impact, given the limited resources available. The committee focused on areas that met three specific criteria: (1) areas in which the United States has existing investments and deep expertise, (2) areas that are identified as high priority by current efforts such as the Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Burden of Disease Study, (3) and areas where specific interventions with strong evidence have been identified. By focusing the analyses and recommendations the committee hopes that it enables U.S. government agencies to optimally deploy scarce resources to interventions with the greatest potential impact to improve health outcomes in a cost-effective manner.

Though this report was not able to highlight every major global health issue, the committee emphasizes that the omission of certain topics is not meant to understate their critical nature. Sectors such as mental health and substance abuse, environmental health (including food safety, air pollution, and water and sanitation issues), refugee health, and health workforce challenges will be crucial factors affecting global health in coming years. In fact, the global burden of mental illness accounted for up to 13 percent of global DALYs (Vigo et al., 2016), and injuries resulted in approximately 8.5 percent of global deaths in 2015 (Wang et al., 2016). Sustaining a health workforce will be important as well. Populations are growing, and health systems are struggling to keep up. The World Health Organization

___________________

3 To obtain the Public Access File, send an email to paro@nas.edu to request information from the Public Access Records Office.

4 The burden of disability associated with a disease or disorder can be measured in units called disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). DALYs represent the total number of years lost to illness, disability, or premature death within a given population. See more at https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/global/index.shtml (accessed April 1, 2017).

estimates the world will be short 12.9 million health care workers by 2035 (WHO, 2013). This shortage could have serious repercussions, which the committee acknowledges as a pressing issue in all countries. As the United States continues to reform health care and medical and public health professional education, it will need to work multilaterally to better understand the causes and effects of workforce reduction in health care.

Despite the focused approach proposed in this report, the committee also strongly believes the United States has an important leadership role to play in shaping policy across global health challenges—even when specifically resourced operational programs are not possible. For example, helping to shape the policy debate on the role of climate change on global health is absolutely critical in light of recent experiences such as the Zika virus. The effects of climate change on health will be felt in the form of malnutrition, drought, extreme temperatures, worsened air quality, and infectious disease spillover—and mitigation of these effects will require work well beyond the health sector, necessitating multidisciplinary collaboration and action (USGCRP, 2016). As such, the committee recognized that an effort on climate change and health would require work and expertise outside the scope of this study, but agrees a multidisciplinary investigation is needed. Across the global health landscape, experts in the U.S. government should continue to participate and shape the discourse on these important topics.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

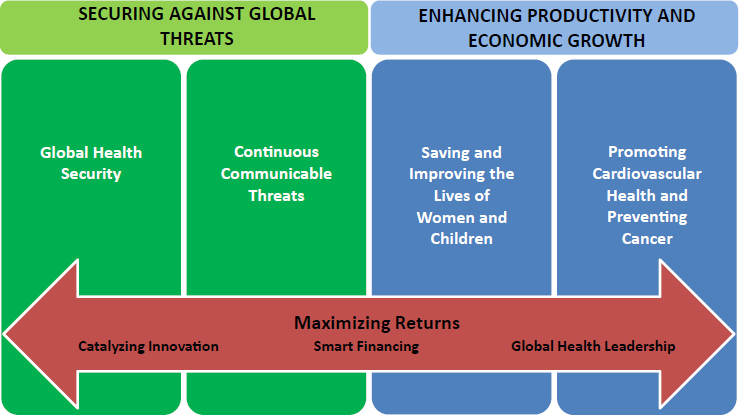

Throughout this report are references to changes that are required for the United States to better participate as a leader in global health in the 21st century. While acknowledging that much progress has been made in the field in the past 10 years, the committee believes there is still much to be done. This report presents the committee’s findings, conclusions, and recommendations for future global health priorities of the U.S. administration and its global health partners. The structure of the report reflects the two key themes motivating the investment in global health by the United States: securing against global threats and enhancing productivity and economic growth. The final section on Maximizing Returns is cross-cutting as its contents encompass methods that should be applied to all of the focus areas within this report (see Figure 1-1).

Chapter 1 provides an overview of the report, as well as important highlights from the previous IOM reports on this topic. Chapter 2 explains prior global health investment and the current spending while also discussing important changes in the global landscape to provide context for later chapters. The first main section of the report, “Securing Against Global Threats,” includes Chapters 3 and 4, and focuses on the broad issues of global health security to the United States and the global community. While

Chapter 3 discusses threats that are immediate, such as pandemic influenza and infectious disease outbreaks, including Ebola, Chapter 4 discusses more persistent and continuing infectious disease threats such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. The second section, “Enhancing Productivity and Economic Growth,” includes Chapters 5 and 6, and explores the justification and methods for building capacity in countries of all income levels to create strong and stable countries. While many arguments can be made that addressing infectious diseases would also have an impact on productivity and economic growth of countries, they often receive disproportionate attention. As a result, the committee has designed the second main section to highlight areas of health that typically do not fall in the spotlight. Chapter 5 addresses the need and justification for saving and improving the lives of women and children, and Chapter 6 discusses the necessity of curbing the burden of NCDs—with a focus on cardiovascular disease and cancer. Finally, the last section of the report, “Maximizing Returns,” encompasses important longer-term approaches and changes to the ways the United States engages in global health to improve effectiveness and cost-efficiency of spending efforts. Within this section, Chapter 7 addresses methods for catalyzing innovation through medical product development and integrated digital health infrastructure. Chapter 8 examines various methods of innovative financing used by many global health players to be more nimble and catalytic in foreign investments. Chapter 9 discusses the critical need for the United States to stay engaged in and committed to international partner-

ships and organizations focused on, or influencing global health, and also explores how the United States can more strategically incorporate health into foreign policy. Finally, Chapter 10 provides a concluding summary of the whole report, highlighting all 14 recommendations.

REFERENCES

Forouzanfar, M. H., A. Afshin, L. T. Alexander, H. R. Anderson, Z. A. Bhutta, S. Biryukov, M. Brauer, et al. 2016. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 388(10053):1659-1724.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1997. America’s vital interest in global health: Protecting our people, enhancing our economy, and advancing our international interests. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2009. The U.S. commitment to global health: Recommendations for the new administration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kassebaum, N. J., M. Arora, R. M. Barber, Z. A. Bhutta, J. Brown, A. Carter, D. C. Casey, et al. 2016. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 388(10053):1603-1658.

Larsen, J., and G. Disbrow. 2017. Project Bioshield and the Biomedical Advanced Research Development Authority: A ten year progress report on meeting U.S. preparedness objectives for threat agents. Clinical Infectious Diseases 64(10):1430-1434.

Millennium Project. 2006. What they are. Washington, DC: The United Nations Millennium Project. http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/goals (accessed March 10, 2017).

PEPFAR (The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief). 2016a. Impact. https://data.pepfar.net (accessed March 9, 2017).

PEPFAR. 2016b. PEPFAR latest global results. Washington, DC: The U.S. President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief.

Ridley, D. n.d. Priority review vouchers. http://priorityreviewvoucher.org (accessed April 2, 2017).

Summers, T. 2013. President’s malaria initiative: Big success from a quiet team. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development). 2016a. 10: A decade of progress. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development.

USAID. 2016b. Acting on the call: Ending preventable child and maternal deaths: A focus on equity. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Agency for International Development.

USAID. 2017. Maternal and child health. https://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do/global-health/maternal-and-child-health (accessed March 10, 2017).

USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program). 2016. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. Edited by A. Crimmins, J. Balbus, J. L. Gamble, C. B. Beard, J. E. Bell, D. Dodgen, R. J. Eisen, N. Fann, M. D. Hawkins, S. C. Herring, L. Jantarasmi, D. M. Mills, S. Saha, M. C. Sarofim, J. Trtanj, and L. Ziska. Washington, DC: U.S. Global Change Research Program.

Vigo, D., G. Thornicroft, and R. Atun. 2016. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. The Lancet Psychiatry 3(2):171-178.

Wang, H., M. Naghavi, C. Allen, R. M. Barber, Z. A. Bhutta, A. Carter, D. C. Casey, et al. 2016. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 388(10053):1459-1544.

WEF (World Economic Forum). 2017. The global risks report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2013. Global health workforce shortage to reach 12.9 million in coming decades. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/health-workforce-shortage/en (accessed January 10, 2017).