8

Smart Financing Strategies

As nations allocate more domestic funds to health and private-sector companies and multilateral organizations contribute more to global aid, the United States has an opportunity to reconsider its strategy for providing foreign assistance for health. Investments need to reflect a globalized world in which the commercial sector, nonprofit and faith-based organizations, and recipient governments all have a partnership role to play. Without this global collaboration and appropriately structured financing mechanisms, further global health progress will be difficult to realize. This chapter discusses several approaches for global health investment, including broad and cross-cutting goals such as global public goods, health system strengthening, and long-term visioning. Also explored are several creative and nontraditional mechanisms of financing global health programs and projects that have emerged in recent years. Finally, with the previous areas as context, this chapter concludes with priorities for U.S. global health investment approaches and mechanisms.

KEY APPROACHES FOR GLOBAL HEALTH INVESTMENT

In addition to the specific areas of focus outlined in the early sections of this report: global health security; continuous communicable diseases; saving and improving the lives of women and children; and the promotion of cardiovascular health and prevention of cancer, there are clear benefits to investing in global public goods, health systems strengthening, and long-term programs that lead to lasting change. Although the majority of global health investments are typically in single, vertical disease programs, these

cross-cutting areas can produce large returns and long-term benefits. Future allocations of foreign assistance for health by the United States should consider investments focused on the greatest return, and also those that require strong leadership and commitment where the United States could play a role, such as the examples described below.

Contributing to Global Public Good

As countries transition out of bilateral aid, donor governments have an opportunity to think more strategically about investing in global public goods instead of direct country assistance (also discussed in Chapter 2). Global public goods are those that require too many resources for one country to create alone, such as research and development advancements in medical products or digital health technologies that can be shared with other entities. There is no “global government” to address these challenges and ensure provision of needed services or products (WHO, 2017), and there is little market incentive to motivate private-sector investment. Unfortunately, the benefits are not always immediately apparent and convincing government leaders to dedicate money to these collaborative goals can be challenging. Furthermore, it is demanding to report and measure concrete progress of the funds and programs dedicated to global public goods, which makes it difficult to directly attribute success to individual investments (Birdsall and Diofasi, 2015). However, returns on investment for global public goods are positive and sustainable. For example, the rotavirus vaccine, developed jointly by India and the United States, has significantly reduced the disease burden of rotavirus in India, translating to improved health and increased economic benefits (see Box 8-1).

As stated above, measurement of global efforts has been difficult, but is not impossible, and new tools are emerging. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recently proposed a new measure, called the total official support for sustainable development (TOSSD), which aims to capture donor spending on global public goods and can facilitate learning exchange, track progress on global challenges, and inform policy discussions using empirical evidence (DAC, 2016). With international collaboration among donors, providers, civil society, multilateral organizations, and the private sector, OECD hopes to drive the operationalization of this measurement framework to have TOSSD enable the international community to monitor resources supporting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) beyond overseas development aid (DAC, 2016). This could also be applied to many global public good efforts involving multiple countries.

Health Systems Strengthening

U.S. global health programs have often been designed and funded with a singular, vertical disease focus, such as The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI). Though they have concrete and specific targets and have a positive impact, they do not sufficiently enable many of the cross-cutting elements necessary to build resilient and robust health systems. To address this in part, previous chapters in this report call for broadening workforce training and task-shifting for community health workers into established platforms like PEPFAR clinics and integrating services in maternal and child health services centers to better incorporate awareness and management of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). As evidenced during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, weak health systems and capabilities—including disease detection or response—contributed to the increased severity of the outbreak in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone (GHRF Commission, 2016). Building resilient health systems allows countries to better respond to global health security threats while simultaneously providing the necessary elements and workforce skills to effectively deliver everyday services such as surveillance, antenatal, well-child, and hypertension services. However, similar to

resource mobilization for global public goods, there are often barriers to funding health system strengthening activities (i.e., financing design, workforce capacity building, and infrastructure building) without clear pathways for attribution or immediate results. Yet, as evidenced in Nigeria during the 2014 Ebola outbreak (see Chapter 3), developing fundamental capabilities can also contain emerging outbreaks and indirectly provide lasting benefits to surrounding populations.

Long-Term Investment for Long Lasting Change

In global health, programs that promise straightforward service delivery or quick results are often able to take precedence over long-term investments that take a much greater time period to demonstrate return on investments (IOM, 2014). For many health and development programs, change is gradual, and social and economic benefits often lag behind the costs and can even occur decades after an initial investment (Stenberg et al., 2014). For countries with scarce resources, it is challenging to make the case for investment in projects or programs that have long-term benefits. For example, building a hospital in a district to prevent the need to travel for health care is an important but costly venture. While it may take 1 year or more to build, the benefits of reducing premature mortality and the resulting demographic dividend may not be realized for decades. Conversely, if that same district has a high burden of malaria, it would be more politically feasible to spend money on quickly procuring mosquito nets with proven effects in malaria prevention—a less costly investment with more short-term, concrete benefits. As a result, best value investments may be ignored as success takes too long to be observed.

By working with other countries to look at the long-term investments, the United States has an opportunity to design efforts that will not only build capacity but also complement global public goods spending. The eradication of smallpox serves as an important success story from this type of investment (see Box 8-2). Though not endemic in many high-income countries in the 1960s, there was still a constant need to vaccinate citizens—including those in high-income countries such as the United States—which was a costly endeavor. The global decision to eradicate smallpox resulted in these costs being avoided, and returns on that moderate investment are still realized each year by the United States and the world (Barrett, 2013; Brilliant, 1985). Similarly, even though only a handful of polio cases are diagnosed each year, continued investment toward polio eradication will be imperative, especially when conflict zones and fragile states continue to enable environments for polio to survive (discussed in Chapter 3). The investment in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988 has already generated net returns of $27 billion, and is projected to reach $40–$50

billion by 2035 (Duintjer Tebbens et al., 2010; GPEI, 2014). Continued support to achieve polio eradication could have as much, if not greater, long-term returns on investment as those realized for smallpox eradication.

Finding: Global public goods, health systems strengthening, and long-term investments in global health are three approaches that prove difficult to procure funds for, due to the challenges associated with attribution and the lack of immediate and clear benefits. Yet, when structured well, these types of investments can have robust and sustainable returns.

CHANGES TO GLOBAL HEALTH FINANCING METHODS

As reviewed in Chapter 2, the growing economies of several low-income countries will propel them toward middle-income status in coming years, which will allow for increased recruitment of domestic sources of financing to support their health programs. The United States can advise these growing economies on best practices for crafting stable tax bases, developing innovative tax initiatives, and restructuring debt ratios as they build up health systems. Through this technical assistance, the United States has a chance to begin to reduce its spending on development assistance for health (DAH). According to a 2016 development cooperation report from OECD, the United States already has begun to reexamine development assistance in order to more effectively achieve sustainable and transformational global health outcomes in light of the financing transitions occurring in global health. The United States has mobilized funds by increasing private capital flow, incorporating more private-sector and nongovernmental organization (NGO) partners, and investing in more science, technology, and innovation (OECD, 2016). As an example, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) strengthened its Development Credit Authority (DCA) to unlock larger sources of capital. Furthermore, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation found that the United States was able to mobilize $10 billion from the private sector through guarantees in 2012–2014 to facilitate participation in the development of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (OECD, 2016). To help achieve the SDGs by 2030, as well as maintain its role as a global health leader and home to numerous multinational businesses, the committee believes that the United States is positioned to tackle global health in a more nimble and flexible way by unlocking additional capital and exploring alternative market strategies. This can be done through assisting countries in their transitions to domestic financing, exploring catalytic financing with the private sector, and creating value in financial structure—all discussed below.

Transitioning to Domestic Financing

Government health expenditure as a source (GHE-S)1 in low-income countries rose 8.5 percent annually from 2000 to 2013 (IHME, 2016). Moreover, middle-income countries’ use of GHE-S actually exceeded external DAH nearly 80 times in 2013 (IHME, 2016), indicating potential for targeted transition for those countries that are ready for more sustain-

___________________

1 GHE-S is defined as expenditures on health from domestic government sources (IHME, 2016).

able sources of funding through domestic resource mobilization (DRM). It will be important to understand that while DRM is playing a larger role globally, this transition will vary based on individual country status. Low-income countries will still need continued DAH from donors to support their health programs, and approaches for middle-income countries will demand a focus on sustainability. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance is well known for its long-term strategy of phasing its partner countries out of support through co-financing. First implemented in 2008, Gavi’s policy designates the size of the domestic contribution based on the country’s ability to pay and has been found to contribute to country ownership and sustainability (Gavi, 2014). Thus far, 2015 has been their most successful year for cofinancing, with countries increasing their spending on vaccines per child by 47 percent in just 1 year (2013–2014) (Gavi, 2015). This policy was also included in Gavi’s 2016–2020 strategy, which recognizes the need to integrate sustainability into country engagement at the beginning of the relationship (Gavi, 2015).

Recognizing this trend, many donors are hoping to help recipient governments transition health programs to domestic sources of financing. Tax revenues are often the main sources of funds that governments have to finance their health systems, and in LMICs tax revenues make up approximately 65 percent of total revenues (IMF, 2011). However, the majority of revenue in LMICs often comes from consumption taxes, which may not create a stable tax base (Reeves et al., 2015). LMICs need a more balanced approach to revenue mobilization, which includes corporate and capital gains taxes. Imposing higher corporate taxes can have important benefits to health, and in countries with particularly low tax revenues (<$1,000 per capita per year), the benefits are substantial (Reeves et al., 2015). Although LMICs have the most to gain from corporate taxes, many countries do not receive adequate revenues from them because they offer low rates to attract businesses (Birn et al., 2017). This trend frequently occurs with the natural and extractive resources industries, robbing governments of much-needed revenue (DanWatch, 2011) and needs to be considered during these transitions.

Catalytic Financing for Leveraging Social and Financial Returns

Global changes have already prompted global health players to find ways to make their investments more productive, and several modalities have emerged and been tested in recent years. There are smaller-scale innovations such as development impact bonds, or models like the Development Innovation Ventures through USAID’s Global Development Lab (GDL). The private sector has also become an active global health player in the past decade, shifting their interests from “corporate social responsibility” line

items to becoming sustainable partners because they see a true return on investment for their business. While it is clear the U.S. government investment in global health should be sustained, the committee sees an opportunity for reshaping investments to be more targeted and catalytic, and leverage more of the existing funds from other sources and mechanisms. Several examples of potential methods are reviewed below.

Small-Scale Innovations

Development Innovation Ventures The GDL within USAID has contributed to nimble and responsive innovative efforts since its creation in 2012. The Development Innovation Ventures initiative was created to find, test, and scale up ideas that could radically improve global prosperity. It invests in ideas across three stages of growth: Stage 1 (Proof of Concept), Stage 2 (Testing at Scale), and Stage 3 (Widespread Implementation) (USAID, 2017), with funding awards increasing as the projects grow. The Development Innovation Ventures model blends best practice strategies in a development approach that includes tiered risk management, economics research, and nonprofit and government development expertise. Hundreds of their projects across the world focus on health at various stages.

Debt buy-downs Debt buy-downs, or conversions, have been used in many low-income countries to decrease country debt and free up resources to fund domestic health programs (Policy Cures, 2012). In a buy-down, a third-party donor such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation pays part of a loan on behalf of a country, allowing that country to spend more of their money on the health program. This can also be tied to performance, where the donor will only pay off their portion of the loan if specific indicators are met (Policy Cures, 2012). One example of this conversion is a bilateral debt swap called “Debt2Health” through the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (Global Fund) that increases both resources for global health and local investment in health (UN Integrated Implementation Framework, n.d.). Similarly, debt swaps allow countries to exchange debt, typically at a discount, for equity or counterpart domestic currency funds to finance a project (Kamel and Tooma, 2005). These can be structured to favor investments in priority sectors, often using them as incentives to encourage privatization or facilitate the return of flight capital (Moye, 2001). While these swapping mechanisms should not be a substitute for current foreign aid, they can be used as an additional tool for mobilizing domestic resources (Kamel and Tooma, 2005).

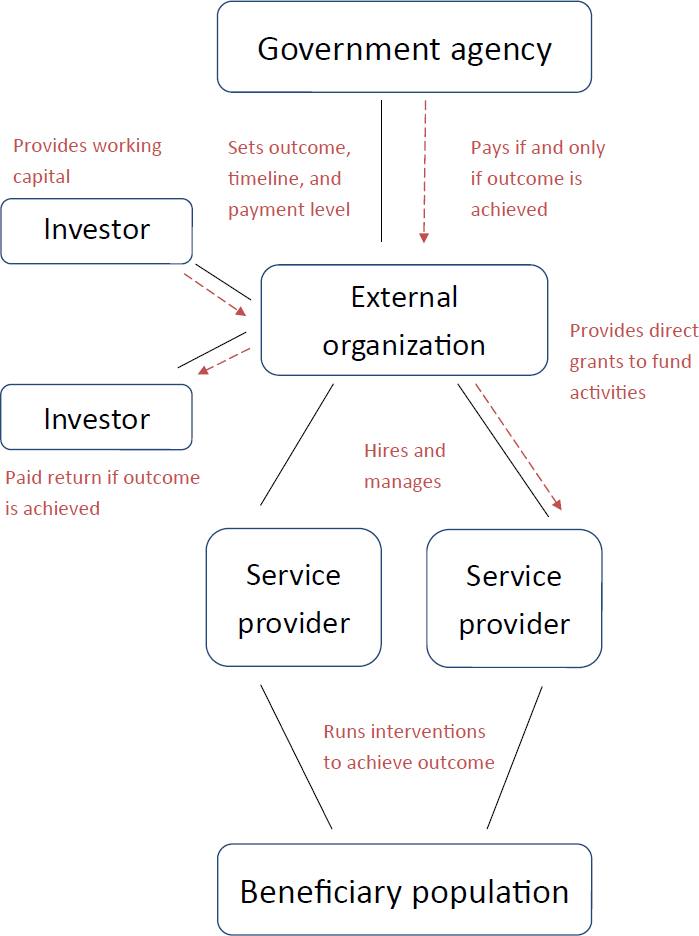

Social and development impact bonds Social impact bonds (SIBs) offer governments a smart way to deliver desired, measurable changes to their

populations by leveraging multiple payers to achieve results. In a traditional model, service providers often cannot afford to make a large investment in a program, conduct a performance assessment, and then receive payment for the successful services offered (Harvard Kennedy School, 2017). The SIB model, which is better characterized as a loan from private funders than an actual bond, minimizes some of the risk associated with the investment in a service program (Harvard Kennedy School, 2017). As described in Figure 8-1, investors provide the upfront investment to a third-party, external organization for a desired government intervention provided by a service provider. Following a successful intervention, the government agency only repays the investor an agreed-upon return on investment for the outcomes (Shah and Costa, 2013). Service providers and governments, therefore, are not punished when interventions fail.

While SIBs are often used for local or state government development, development impact bonds (DIBs) are used for international development. Although DIBs bear many similarities to SIBs, external funders, rather than national governments, repay outcome payments (Shah and Costa, 2013). One example is the Mozambique Malaria Performance Bond (Saldeinger, 2013), sponsored by Nando’s restaurant chain. Several years ago, leaders at Nando’s recognized a lack of creativity in reaching the populations most vulnerable to malaria in Mozambique (Devex Impact, 2017). In response, they collaborated with the Ministry of Health in Mozambique to offer financial support in an effort to increase efficiency of malaria interventions (Devex Impact, 2017) with a goal of reducing malaria incidence by 30 percent or more after year 3. If this target is achieved, the Mozambique Malaria Performance Bond will repay the entire principal from Nando’s and other investors with 5 percent interest. If the interventions are unsuccessful, the investors will be repaid 50 percent of their principal, with no interest (Devex Impact, 2017).

SIBs and DIBs have important limitations. First, because the success of these partnerships is contingent on a specific and measurable goal, sufficient historical data are required in order to create the goal (Shah and Costa, 2013). Second, SIBs and DIBs should not be used for essential services or for programs in which cessation would harm a population (Shah and Costa, 2013). Finally, the SIB process involves many steps, and therefore the partnership requires a large investment of time and resources to ensure success (Shah and Costa, 2013). Given that understanding, if executed successfully, SIBs and DIBs can be very helpful to governments.

Finding: Many small-scale innovations exist that can be replicated and used more widely to create more opportunities in global health.

SOURCE: This material [Social Finance: A Primer] was published by the Center for American Progress (www.americanprogress.org).

Private Corporations and Investors

The private sector has increasingly become a more active funding partner in global health projects in recent years. Their growing role will be critical in order to achieve many of the SDGs, in particular SDG 17, which calls for revitalizing global partnerships for sustainable development. Because of the inherent desire of the private sector to constantly improve their bottom line, people in every country may have a difficult time trusting private companies to make decisions that will improve outcomes for people living in poverty. However, encouraging private companies to use their skills and resources to both improve their markets and future business trajectories, while simultaneously contributing to social good, can be a sustainable strategy to improving global health outcomes. The private sector has a clear interest in preventing deaths and improving living conditions for populations, both of which promote economic development, create new markets, and contribute to better operating conditions for businesses (Sturchio and Goel, 2012). A notable example of private engagement in the global health space is the rise of product development partnerships, which use public and philanthropic funds to incentivize research and development. These have become more common in recent years and have been able to provide much-needed drugs at an affordable level (Mahoney, 2011). With 82 percent of capital that reaches the developing world coming from the private sector, it is imperative to ensure that these funds, in addition to the private sector’s expertise, bolster the development agenda effectively (Nathan, 2017).

While private companies’ philanthropic efforts have historically been categorized as corporate social responsibility, the last decade has seen a shift toward global health investment as a way to create shared value in their efforts. The shared value management strategy seeks to generate economic value while also addressing social problems (Porter and Kramer, 2011). Through linking social and business impact, companies can then move toward greater innovation and value creation. Notable methods of shared value that companies can use include reconceiving products and markets, redefining productivity in the value chain, and enabling local cluster development (Porter and Kramer, 2011). Greater collaboration among corporations, NGOs and governments for shared value will be important for further success (FSG, 2016), with a specific focus on leveraging the data collected by nonprofits and the public sector to bridge the gap between a shared value intervention and detecting evidence of benefits—though benefits will take time to be realized. However, this term of shared value may be too narrow to encompass the many efforts by companies to seek and obtain sustainable commercial returns in LMICs while also providing health products and needed services. For example, once generic alternatives were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2006,

the PEPFAR program and the World Health Organization (WHO) began increasing demand for inexpensive but quality antiretroviral drugs, leading to a competitive market that transformed the prospects for a number of generic companies (Waning et al., 2010).

Business models that are fit for purpose like many found in resource-constrained settings are more likely to be sustainable over the long run. Some companies have employed the “triple bottom line” strategy as a core element of their business to consider social, financial, and environmental factors when making important decisions. This focus on more comprehensive investment results has been growing across businesses and nonprofit organizations, with an eye for improved sustainable growth (Slaper and

Hall, 2011). To more clearly illustrate some of these concepts and how they can fit into global health, the United Nations Global Compact and KPMG produced a matrix that examines opportunities for the private sector for alignment of core competencies of their business with social good or engagement within each of the SDGs (KPMG and United Nations Global Compact, 2015). See Box 8-3 for various examples of private-sector involvement in global health, including shared value, triple bottom line approaches, and alignment of core competencies.

Healthy workforce overlap For multinational companies that depend on a workforce in LMICs, the motivation to become more involved in global

community health is even clearer. As mentioned in Chapter 4, the private sector has played a particularly important in role in malaria control and elimination, with the much direct financing and in-kind donations being provided by the oil/gas and mineral industries. For example, the AngloGold Ashanti mining company faced a significant problem of a 24 percent malaria incidence rate affecting its workforce across multiple African countries. Worker absenteeism and low productivity came with serious costs to the company. In response, AngloGold Ashanti implemented integrated malaria control programs in Ghana in 2005 that led to a 72 percent decrease in disease burden in the first 2 years; the reduction in treatment costs saved the company around $600,000 per year by 2013 (FSG, 2017). At another mine in Tanzania, AngloGold Ashanti developed a public–private partnership (PPP) with international development organizations and the National Medical Research Institute of Tanzania to build on the program. The first phase focused only on employees and achieved a 50 percent reduction in malaria, but expansion to other mining operations was able to cover more than 90 percent of the mine’s employees and 100,000 community members (AngloGold Ashanti, 2013).

An example with a multi-country focus, the Lubombo Spatial Development Initiative (LSDI) was a PPP formed in 2000 to address malaria control in southern Africa including Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland (Moonasar et al., 2016) and improve the health and economic viability of the region. BHP Billiton, a large resource company with 17,000 employees in South Africa and Mozambique and one of the founding partners of LSDI, had a keen interest as their workforce was continually threatened by malaria (WEF, 2006). Since the majority of the new malaria cases in northeastern South Africa and Swaziland, both wealthier middle-income countries, were imported from neighboring Mozambique, LSDI understood that to truly eliminate malaria there was a need to take a targeted approach at control measures in Mozambique. Following the implementation of control measures in Mozambique alone, Swaziland saw a 95 percent reduction in malaria cases between 2000 and 2004 (Laxminarayan, 2016).

U.S. public–private partnerships in research and development As discussed in Chapter 7, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) appreciates that the pervasive challenges of medical countermeasure development and antimicrobial resistance require a global effort. They use PPPs to recruit skilled institutions and companies of all sizes to solve this global problem of medical product development in an uncertain market. The Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator, or CARB-X, was created in 2016 as the world’s largest global antibacterial public–private partnership focused on preclinical discovery and early stage development of new antimicrobial products (HHS, 2016).

CARB-X is a collaboration between National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, BARDA, and four life science accelerators, with each partner playing a unique role in their shared goal to set up a diverse portfolio with more than 20 high-quality antibacterial products—dozens more than a single company would normally pursue. CARB-X plans to accomplish their goals, and get more innovative products into clinical testing by leveraging $250 million from BARDA in the first 5 years, with matching funds from the Wellcome Trust and the AMR Centre.

In addition to the CARB-X partnership, BARDA is also pursuing a pipeline of new antibiotics through a mechanism called the Other Transaction Authority (OTA), which allows BARDA and partners to diversify their investment across a portfolio of compounds. Traditional federal contracting often requires significant costs and time, but with more flexibility to change directions mid-course within the portfolio, OTA offers time-saving benefits as well. All strategic decision making is done jointly with BARDA and the senior staff at the companies involved. The portfolio model enables the partnership to adjust plans according to the most promising candidates with the cost and risk shared between the parties, something that was not possible through more traditional funding mechanisms (Houchens, 2015). The Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense recommended further use of this mechanism by BARDA, but has only found one instance of use since October 2015 (Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense, 2016). The committee supports expanded use of this type of flexible funding mechanism, also called for by the Senate Committee on Appropriations.2

Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility

Launched by the World Bank in May 2016 at the G7 Ministers of Finance meeting, the Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF) is designed as a pandemic emergency response mechanism (World Bank, 2016). This mechanism is only to be used in emergency response; it is not a substitute for preparedness investments. The World Bank understands that quality, resilient health systems and strong public health capabilities are crucial, but once an emergency event occurs, there is also a need to act quickly. The PEF accelerates and improves emergency response immediately, and similar to the Public Health Emergency Fund in the United States, described in Chapter 3, the PEF fills a gap in the current global financing architecture and is activated once an outbreak triggers a pre-designated level of severity. It is financed through an insurance window, with funding provided by resources from the reinsurance market combined with catastrophe bond

___________________

2 U.S. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill. Report 114-74. Senate. 2016.

proceeds, as well as a cash window, providing more flexible funding to address a larger set of emerging pathogens with uncertain consequences. Japan provided the first $50 million in funding commitment in 2016, and the World Bank expects the PEF to be active in 2017.

Finding: The private sector has grown as an active global health stakeholder in recent years to go beyond simply involvement through corporate social responsibility to aligning their core business competencies with social good and improvement of health outcomes. As evidenced by the number of companies investing their own resources, the private sector can be leveraged as a sustainable partner for governments in the future of global health.

Value in Financial Structure

The traditional aid model that provides a scheduled stream of funds does not produce the best incentives or results and is often too highly focused on short-term outcomes or inputs into their system instead of long-term outcomes or outputs. As part of the reevaluation of the U.S. global health enterprise strategy to sustainably provide aid and achieve the goals set in this report in a cost-effective manner, the U.S. government could turn to successful multilateral organizations such as Gavi for new mechanisms. These organizations have successfully engaged in partnerships and market-shaping models to make their money go farther. For example, the Global Fund only finances programs when there is assurance that they do not replace or reduce other sources of health funding, and it actively seeks opportunities to catalyze additional donor and recipient investment through grants and other supportive structures (Brenzel, 2012). Additionally, the World Bank and other development banks have pursued better ways of putting money toward development, and tying results to financing, with much success. The committee identified front-loading investments and results-based financing as two alternative financing mechanisms that bring more value for money to U.S. global health spending.

Front-Loading Investments

Front-loading an investment allows more resources to be used initially while maintaining the level of investment over time. The theoretical benefit of this is that having a larger pool of resources upfront will enable a program to achieve its goals faster (Barder and Yeh, 2006). For example, in the context of an advanced-purchase agreement for vaccines, a front-loaded payment would increase the incentive for a manufacturer to bring products

to market quickly (Berndt and Hurvitz, 2005) and provide a more efficient use of resources over time (Barder and Yeh, 2006).

Gavi employs these types of various alternative financing models to avoid defaulting, and ensuring sustainability of services provided in the countries involved in their partnership. As an example, their Advanced Market Commitment (AMC) generates incentives for vaccine manufacturers to produce affordable vaccines for the world’s poorest countries. Following the launch of its pneumococcal conjugate pilot in 2007, accelerated immunization coverage against pneumococcal disease was documented across 53 Gavi countries, with 49 million children found to be fully immunized (BCG, 2015). The AMC secures lower prices for vaccines and increases access for the world’s poorest children more quickly than before. Recommendations for future AMCs or other innovative financing mechanisms noted that successful engagement with the pharmaceutical industry is critical to improve sustainability of initiatives and enable manufacturers to shift from a corporate social responsibility-based approach to a more commercially viable strategy (BCG, 2015) as highlighted in the previous sections of this chapter.

Through another front-loading investment strategy called the International Finance Facility for Immunization (IFFIm), established in 2006, Gavi accelerates the availability and predictability of funds to support immunization programs by issuing bonds in the capital markets and converting long-term donor pledges into immediate cash resources (Bilimoria, 2016). This type of mechanism, and others like it, was encouraged for replication by the Action Agenda at the Financing Conference for Development in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 2015 (UN, 2015). Through an independent evaluation in 2011, findings demonstrated that IFFIm was financially efficient, had achieved supranational status in capital markets, and was a robust and flexible model in challenging environments. Most importantly, it was credited with saving at least 2.75 million lives (Pearson et al., 2011).

Results-Based Financing

Results-based financing (RBF) programs for health transfer money or goods—either to patients when they take health-related actions or to health care providers when they achieve performance targets (Morgan, 2009). Currently, the RBF model is being supported by the World Bank through the Health Results Innovation Trust Fund, which was launched in 2007 with a special focus to achieve the women’s and children’s health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Following smaller-scale pilot grants, the RBF activities and relevant network have grown in both supply and demand. In fact, RBF programs around the world have demonstrated evidence-based transformational effects to maternal and child health. For

example, the probability of in-hospital neonatal mortality of babies whose mothers enrolled in Plan Nacer, a RBF program, dropped by 74 percent in Argentina; in Nigeria, the rate of modern contraceptive use in RBF areas was approximately twice that of non-RBF areas at 21.5 percent and 10 percent, respectively (World Bank, 2014). The researchers were also able to show that the quality of care improved in these areas that implemented RBF practices.

RBF programs can also improve in-country harmonization of comprehensive strategies for targeted sector services, such as maternal and child health. For example, the government of Rwanda directs its alignment efforts underneath its RBF program, inviting donors to provide support for indicators that they have already designated (World Bank, 2014). This method of harmonization allows for reduced transaction costs and improved efficiency in reporting and verification for partners. Importantly, this method also provides a solution to the problem of poor alignment of donor goals and national priorities that has emerged in recipient countries.

Global Financing Facility Following this trend of increased progress and successful results through RBF, the World Bank Group and the governments of Canada, Norway, and the United States announced in September 2014 the creation of the Global Financing Facility (GFF) to mobilize support for developing countries’ plans to accelerate progress on the MDGs and end preventable maternal and child deaths by 2030 (Claeson, 2017; GFF, 2016a). The GFF, the financing arm of Every Woman Every Child,3 is a multi-stakeholder partnership that supports country-led efforts to improve the health of women, children, and adolescents by focusing on a specific set of challenges—including health financing and health systems. The main aim of the GFF is to close the $33 billion financing gap to meet these challenges in 63 target countries, with the national governments leading the process through their own country platform of stakeholders (GFF, 2016b). Thus far, 16 “front runner” countries have begun piloting the GFF process.4 The first step is the creation of an Investment Case, which establishes a unique set of evidenced-based interventions for a national government. Of the 16 countries that have initiated the GFF process, 7 have begun to implement their

___________________

3 Every Woman Every Child is a global movement that puts into action WHO’s Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescents’ Health. Launched by the UN Secretary-General in 2010, Every Woman Every Child aims to mobilize national governments, international organizations, the private sector, and civil society to solve the health issues that women, children, and adolescents face around the world (Every Woman Every Child, 2016).

4 The countries include Bangladesh, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, and Vietnam (Claeson, 2017).

cases. To help countries successfully do so, GFF strives to move away from traditional development assistance, by using four smart financing pathways: improved efficiency, increased domestic resource mobilization, increased and better aligned external financing, and leveraged private-sector resources (Claeson, 2017). The first two pathways are especially useful given that 20 to 40 percent of health expenditures are lost due to inefficiency and that GFF modeling suggests that the combination of economic growth, tax base increases, and increased prioritization of health would close 71 percent of the $33 billion financing gap (Claeson, 2017). Though the majority of GFF’s efforts are aimed at national governments, it also supports efforts at the subnational level.

Finding: Creating value in financial structure, through mechanisms like front-loading investments and results-based financing can secure lower prices for commodities, save lives, and encourage sustainability of programs and health outcomes.

PRIORITIES FOR U.S. GLOBAL HEALTH PROGRAMS

Moving into the next decade of global health, it is clear that the aspirational global health goals set across many sectors will demand more than the previous DAH structures can offer. The questions then become, how can U.S. government programs support growing economies of middle-income countries to take on more ownership of their health programs? How can all governments continue to attract investment and technical expertise from private companies as sustainable partners? What do these private companies need in order to feel comfortable investing their own resources? And finally, what can the United States do differently to make investments in global health more efficient and cost-effective?

Supporting Domestic Resource Mobilization

For countries with burgeoning economies and middle-classes, the economic case can be made to ministers of finance that investments in health infrastructure and personnel can be critical for building ownership and driving returns. Investment in community health workers results in a return on investment as high as 10:1 according to the WHO report Strengthening Primary Health Care through Community Health Workers (2015). The report also recommended that bilateral donors “allow for and actively promote the use of disease-specific funding for integrated . . . community health worker plans” (Dahn et al., 2015, p. 25). As countries do shift to domestic financing, the United States can advise nations in ways to structure their debt ratios and tax bases, and develop tax initiatives in order to

create new revenue streams or make better use of existing donor funds to strengthen their health systems. Other types of support could include engagement with ministries on system design and financing to assist in plan design, model refinement and expansion, return on investment analysis and financial plan execution. Further nontraditional support could include intellectual property and knowledge management such as case studies on financing pathways, documenting funding flows, and South-South capacity building functions (Qureshi, 2016).

This advisory role is beginning to take shape, with the Sustainable Finance Initiative (SFI) for HIV/AIDS, an interagency partnership among the Bureau for Economic Growth, Education and Environment at USAID, PEPFAR, and the U.S. Treasury. SFI works through other countries’ ministries of health and finance to help national governments examine methods of increasing their funding commitment to HIV/AIDS (USAID, 2016). Five countries already have representatives from the U.S. Treasury working in the USAID mission office to ensure this is done correctly and sustainably from the outset. As an example, SFI’s impact in Kenya has contributed to an increase of $30–$40 million in new domestic spending being allocated to HIV response in each of the next 5 years. Finally, creating more flexibility for innovative finance can better support this transition to domestic resource mobilization. As an example, USAID could allow development credit authority greater latitude to apply certain restrictions where the ultimate outcome will catalyze additional private-sector resources and the capital markets. These restrictions could include limited ability to guarantee sovereigns, or caps on total amount of risk guaranteed in a development credit authority structure (Qureshi, 2016).

Attracting Investment from Private Companies

To continue to attract new money and maintain the interest of the private sector, U.S. programs need to increase their flexibility in developing innovative financing products and modalities. Examples could include working with the finance sector to push the envelope on innovative sources of financing, or crowding-in5 private-sector capital (Qureshi, 2016). Governments can crowd-in additional funding sources by increasing the demand for goods through public funds and sharing risk in various ways, which then catalyzes private investment that would not have otherwise taken place (Powers and Butterfield, 2014). Additionally, to provide more certainty for the private sector in investing, U.S. government global health

___________________

5 Crowding-in is an economic principle in which private investment increases as debt-financed government spending increases. This is caused by government spending boosting the demand for goods, which in turn increases private demand for new output sources.

programs could include a provision to provide matching funds for public–private partnerships, which have proven to be effective in encouraging companies to invest through other programs such as PEPFAR, Power Africa, and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (Sturchio and Schneider, 2017). For countries that the United States will continue to support through DAH, current investments can be made more effective and efficient, thus helping to stretch farther the dollars being spent. This could be accomplished through integration of services as discussed in Chapter 6 and through the many PPPs highlighted in this report, so an established platform like PEPFAR can be used to address additional health burdens without much increase in cost.

Stressing Increased Efficiency and Cost-Effectiveness

Overall, many viable tools, including debt buy-downs, social impact bonds, and other mechanisms not discussed in this chapter such as impact investing, microfinance schemes, traditional equity investments can improve the accessibility of funds and efficiency of global health programs (Sturchio and Schneider, 2017). The historical challenges and limitations of traditional bilateral aid from the U.S. government make the contracting process slow and dated, and the outcomes not as effective as they could be. These new methods, though not risk-free, offer a fresh perspective to aid disbursement and new opportunities. Many experts have reviewed and assessed various innovative financing mechanisms in much more detail than is called for in this report, but these expert analyses should be consulted when designing changes to global health investments to ensure fit-for-purpose and avoid re-creation of mechanisms (Atun et al., 2012; de Ferranti et al., 2008; Sturchio and Schneider, 2017). Encouraging more cooperation between U.S. development finance tools can also maximize impact when multiple agencies are brought together to work across sectors.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Current U.S. global health financing is focused largely on immediate disease-specific priorities such as HIV/AIDS or malaria. This financial support is seen as development and humanitarian assistance for strategic partner countries, rather than as a means of achieving long-term goals of building global health systems and platforms that are disease-agnostic and can respond rapidly and flexibly to emerging diseases that threaten the entire world, including the United States. However, these cross-cutting systems and platforms can produce large returns and long-term benefits. For example, smallpox eradication saves the United States the one-time expenditures it invested every 26 days, and the global benefits of avoided

infections outweigh the global costs 159:1 (Barrett, 2013). Similarly, efforts toward polio eradication are projected to generate net returns of up to $50 billion by 2035 (Duintjer Tebbens et al., 2010), but even more returns will remain out of reach if the handful of polio cases diagnosed each year continue and annual funding is still required.

As countries continue to grow economically, their needs will change from direct support for drugs, diagnostics, and other commodities to technical support and sustainable financing from multiple sources. Additionally, current investments in global health also can be made more effective and efficient. For example, existing programs such as PEPFAR or the work of BARDA can be augmented through public–private partnerships to have a greater impact on health outcomes in countries. Furthermore, there are opportunities for working with the finance sector to allow more flexibility and innovation in financing mechanisms for programs. Given the limitations of traditional federal bilateral aid from the U.S. government, new methods such as impact investing, microfinance schemes, and equity investments could improve the accessibility of funds and efficiency of global health programs (Sturchio and Schenider, 2017).

Finally, the private sector has a clear interest in preventing deaths and improving living conditions for many international populations—both of which promote economic development, create new markets, and contribute to better operating conditions for businesses (Sturchio and Goel, 2012). As 82 percent of capital reaching LMICs comes from the private sector, there are many opportunities for both donors and national recipient governments to bolster the health and development agenda more effectively (Nathan, 2017).

Conclusion: The U.S. government needs to conduct more strategic and systematic assessments with an eye toward making long-term investments in global health instead of focusing on short-term expenditures.

Conclusion: Increased financial gains in middle-income countries and a plethora of new and committed global health partners have created an opportunity for the United States to take smarter and more creative directions when financing global health programs. A variety of innovative financing mechanisms are being employed around the world, and there is a need for expansion and diversification of current U.S. financing methods.

Conclusion: Thinking more strategically about how to help countries transition out of bilateral aid programs and optimize their use of domestic resources in a sustainable way is an important future

role of the United States. Providing assistance to low- and middle-income countries in structuring debt ratios and tax initiatives in ways that can build stronger and more holistic health systems can provide multiple returns on investments, and is a next step for donor governments.

Recommendation 12: Transition Investments Toward Global Public Goods

The U.S. Agency for International Development, the U.S. Department of State, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should, together, systematically assess their approach to global health funding with an eye toward making long-term investments in high-impact, country-level programs. The focus should be on programs that both build national health systems and provide the greatest value in terms of global health security (to prevent pandemics), as well as respond to humanitarian emergencies and provide opportunities for joint research and development for essential drugs, diagnostics, and vaccines that will benefit many countries, including the United States.

Recommendation 13: Optimize Resources Through Smart Financing

Relevant agencies of the U.S. government should expand efforts to complement direct bilateral support for health with financing mechanisms that include results-based financing; risk sharing; and attracting funding from private investment, recipient governments, and other donors.

- The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) should structure their financing to promote greater country ownership and domestic financing. Assistance should be provided in developing innovative financing products/modalities and in working with the finance sector to push the envelope on innovative sources of financing, crowding in private-sector capital.

- USAID and PEPFAR should engage with ministries on system design and financing to assist in plan design, model refinement and expansion, return-on-investment analysis, and financial plan execution.

- USAID should expand the use and flexibility of such mechanisms as the Development Credit Authority, and the U.S. Treasury, the U.S. Department of State, and USAID should motivate the World Bank; the International Monetary Fund;

the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, respectively, to promote transitioning to domestic financing, assist countries in creating fiscal space for health, leverage fiscal policies to improve health, and attract alternative financing sources.

REFERENCES

AngloGold Ashanti. 2013. Creating a sustainable solution for malaria in Continental Africa region. http://www.anglogold-ashanti.com/en/Media/Our-Stories/Pages/Creating-a-sustainable-solution-for-malaria-in-Continental-Africa-Region.aspx (accessed February 13, 2017).

Atun, R., F. M. Knaul, Y. Akachi, and J. Frenk. 2012. Innovative financing for health: What is truly innovative? The Lancet 380(9858):2044-2049.

Barder, O. M., and E. Yeh. 2006. The costs and benefits of front-loading and predictability of immunization. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Barrett, S. 2013. Economic considerations for the eradication endgame. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 368(1623):20120149.

BCG (Boston Consulting Group). 2015. The Advance Market Commitment pilot for pneumococcal vaccines: Outcomes and impact evaluation. Boston, MA: Boston Consulting Group.

Bennett, A., N. Bar-Zeev, and N. A. Cunliffe. 2016. Measuring indirect effects of rotavirus vaccine in low income countries. Vaccine 34(37):4351-4353.

Berndt, E. R., and J. A. Hurvitz. 2005. Vaccine advance-purchase agreements for low-income countries: Practical issues. Health Affairs 24(3):653-665.

Bilimoria, N. 2016. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Paper read at Global Health and the Future of the United States: A Changing Landscape of Global Health, December 6, 2016, Washington, DC. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Global/USandGlobalHealth/Global-Health-and-The-Future-of-the-US/Meeting-2-Files/BilimoriaPresentation.pdf (accessed December 10, 2016).

Birdsall, N., and A. Diofasi. 2015. Global public goods that matter for development: A path for US leadership. The White House and the world: Practical proposals on global development for the next US president, edited by N. Birdsall and B. Leo. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Birn, A.-E., Y. Pillay, and T. H. Holtz. 2017. Textbook of global health. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense. 2016. Biodefense indicators: One year later, events outpacing efforts to defend the nation. Arlington, VA: Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense.

Brenzel, L. 2012. Global and donor financing. In MDS-3: Managing access to medicines and health technologies, edited by M. Ryan. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health.

Brilliant, L. B. 1985. The management of smallpox eradication in India. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Claeson, M. 2017. The Global Financing Facility: Towards a new way of financing for development. The Lancet. 389(10079):1588-1592.

DAC (Development Assistance Committee). 2016. TOSSD: A new statistical measure for the SDG era. Washington, DC: The Development Assistance Committee, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Dahn, B., A. T. Woldemariam, H. Perry, A. Maeda, D. von Glahn, R. Panjabi, N. Merchant, K. Vosburg, D. Palazuelos, C. Lu, J. Simon, J. Pfaffmann, D. Brown, H. Austin, P. Heydt, and C. Qureshi. 2015. Strengthening primary health care through community health workers: Investment case and financing recommendation. http://www.who.int/hrh/news/2015/CHW-Financing-FINAL-July-15-2015.pdf?ua=1 (accessed January 10, 2017).

DanWatch. 2011. An investigation of tax payments and corporate structures in the mining industry of Sierra Leone: Not sharing the loot. http://www.resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/Not_Sharing_the_Loot.pdf (accessed March 20, 2017).

de Ferranti, D., C. Griffin, M. L. Escobar, A. Glassman, and G. Lagomarsino. 2008. Innovative financing for global health: Tools for analyzing the options. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Devex Impact. 2017. Goodbye malaria: Mozambique Malaria Performance Bond. https://www.devex.com/impact/partnerships/goodbye-malaria-mozambique-malaria-performance-bond-362 (accessed February 13, 2017).

Duintjer Tebbens, R. J., M. A. Pallansch, S. L. Cochi, S. G. Wassilak, J. Linkins, R. W. Sutter, R. B. Aylward, and K. M. Thompson. 2010. Economic analysis of the global polio eradication initiative. Vaccine 29(2):334-343.

Every Woman Every Child. 2016. About. https://www.everywomaneverychild.org/about (accessed April 15, 2017).

Fenner, F., D. A. Henderson, I. Arita, Z. Jezek, and I. D. Ladnyi. 1988. Smallpox and its eradication, history of international public health no. 6. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

FSG. 2016. Competing by saving lives: Pushing the frontier for shared value in health: Report to participants. New York: Frontier Strategy Group.

FSG. 2017. Anglogold Ashanti malaria program. https://sharedvalue.org/groups/anglogold-ashanti-malaria-program (accessed February 13, 2017).

Gavi (Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance). 2014. Co-financing policy evaluation. http://www.gavi.org/results/evaluations/co-financing-policy-evaluation (accessed February 13, 2017).

Gavi. 2015. Keeping children healthy: The Vaccine Alliance progress report 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

GFF (Global Financing Facility). 2016a. Global Financing Facility partners. https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/about/partners (accessed March 17, 2017).

GFF. 2016b. Global Financing Facility introduction. https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/introduction (accessed March 17, 2017).

GHRF Commission (Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework for the Future). 2016. The neglected dimension of global security: A framework to counter infectious disease crises. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/21891.

GPEI (Global Polio Eradication Initiative). 2014. Economic case for eradicating polio. Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

Harvard Kennedy School. 2017. Pay for success: Social impact bonds. http://govlab.hks.harvard.edu/social-impact-bond-lab (accessed February 13, 2017).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2016. CARB-X: Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator. https://www.phe.gov/about/barda/CARB-X/Pages/default.aspx (accessed February 13, 2017).

Houchens, C. 2015. Innovative partnerships support antibiotic development. https://www.phe.gov/ASPRBlog/pages/BlogArticlePage.aspx?PostID=157 (accessed February 13, 2017).

IHME (Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation). 2016. Financing global health 2015: Development assistance steady on the path to new global goals. Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2011. Revenue mobilization in developing countries. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2014. Investing in global health systems: Sustaining gains, transforming lives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kamel, S., and E. A. Tooma. 2005. Exchanging debt for development: Lessons from the Egyptian debt-for-development swap experience. Giza, Egypt: Economic Research Forum.

KPMG (Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler) and United Nations Global Compact. 2015. SDG industry matrix: Healthcare & life sciences. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/3111 (accessed February 13, 2017).

Laxminarayan, R. 2016. Trans-boundary commons in infectious diseases. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 32(1):88-101.

Mahoney, R. T. 2011. Product development partnerships: Case studies of a new mechanism for health technology innovation. Health Research Policy and Systems 9(1):33-41.

Megiddo, I., A. R. Colson, A. Nandi, S. Chatterjee, S. Prinja, A. Khera, and R. Laxminarayan. 2014. Analysis of the universal immunization programme and introduction of a rotavirus vaccine in India with Indiasim. Vaccine 32 (Suppl 1):A151-A161.

Miller, M., S. Barret, and D. A. Henderson. 2006. Control and eradication. In Disease control priorities in developing countries. Vol. 2, edited by D. T. Jamison, J. G. Breman, A. R. Measham, G. Alleyne, M. Cleason, D. B. Eavns, P. Jha, A. Mills, and P. Musgrove. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Moonasar, D., R. Maharaj, S. Kunene, B. Candrinho, F. Saute, N. Ntshalintshali, and N. Morris. 2016. Towards malaria elimination in the MOSASWA (Mozambique, South Africa and Swaziland) region. Malaria Journal 15(1):419.

Morgan, L. 2009. Performance incentives in global health: Potential and pitfalls. https://www.rbfhealth.org/sites/rbf/files/RBF_FEATURE_PerfIncentivesGlobalHealth.pdf (accessed February 13, 2017).

Moye, M. 2001. Overview of debt conversion. London, UK: Debt Relief International Ltd.

Nathan, T. 2017. 5 ways to make blended finance work. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/ways-to-make-blended-finance-work (accessed February 13, 2017).

NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). 2015. Indo-U.S. vaccine action program overview. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/indo-us-vaccine-action-program-overview (accessed February 13, 2017).

Novo Nordisk. 2013. Where economics and health meet: Changing diabetes in Indonesia. Novo Nordisk.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2016. Development co-operation report 2016: The sustainable development goals as business opportunities. Paris, France.

Ogola, E. N. August 2015. Healthy Heart Africa: The Kenyan experience. Paper presented at Pan-African Society of Cardiology Hypertension Task Force Meeting, London, United Kingdom. http://www.pascar.org/uploads/files/HEALTHY_HEART_AFRICA_Elijah_Ogola.pdf (accessed February 18, 2017).

Pearson, M., J. Clarke, L. Ward, C. Grace, D. Harris, and M. Cooper. 2011. Evaluation of the International Finance Facility for Immunization (IFFIm). London, UK: Health and Life Science Partnership.

Policy Cures. 2012. Policy brief 6: Debt buydowns or conversions. Paper presented at Asia-Pacific Development Summit, Jakarta, Indonesia. http://policycures.org/downloads/Policy%20Brief%206%20-%20Debt%20Conversion.pdf (accseed March 5, 2017).

Porter, M., and M. Kramer. 2011. Creating shared value. Harvard Busisness Review. https://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value (accessed April 15, 2017).

Powers, C., and W. M. Butterfield. 2014. Crowding in private investment. In Frontiers in development: Ending extreme poverty, edited by R. Shah and N. Unger. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development.

Qureshi, C. 2016. Financing community health: Briefing for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Paper read at Global Health and the Future of the United States: A Changing Landscape of Global Health, Washington, DC. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Global/USandGlobalHealth/Global-Health-and-The-Future-of-the-US/Meeting-2-Files/Claire-Qureshi-Presentation.pdf (accessed December 15, 2016).

Reeves, A., Y. Gourtsoyannis, S. Basu, D. McCoy, M. McKee, and D. Stuckler. 2015. Financing universal health coverage—effects of alternative tax structures on public health systems: Cross-national modelling in 89 low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 386(9990):274-280.

Saldeinger, A. 2013. How a restaurant chain pioneered a social impact bond to fight malaria. https://www.devex.com/news/how-a-restaurant-chain-pioneered-a-social-impact-bond-to-fight-malaria-82212 (accessed February 13, 2017).

Seymour, J. 2004. Eradicating smallpox. In Millions saved: Proven successes in global health. Vol. 1, edited by R. Levine and The What Works Working Group. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Shah, S., and K. Costa. 2013. Social finance: A primer. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2013/11/05/78792/social-finance-a-primer (accessed February 13, 2017).

Shared Value Initiative. 2017. Novartis delivers healthcare and education to remote communities. https://sharedvalue.org/examples/arogya-parivar-local-healthcare-delivery-and-education (accessed March 20, 2017).

Slaper, T. F., and T. J. Hall. 2011. The triple bottom line: What is it and how does it work? Indiana Business Review 86(1):4-8.

Stenberg, K., H. Axelson, P. Sheehan, I. Anderson, A. M. Gülmezoglu, M. Temmerman, E. Mason, H. S. Friedman, Z. A. Bhutta, J. E. Lawn, K. Sweeny, J. Tulloch, P. Hansen, M. Chopra, A. Gupta, J. P. Vogel, M. Ostergren, B. Rasmussen, C. Levin, C. Boyle, S. Kuruvilla, M. Koblinsky, N. Walker, A. de Francisco, N. Novcic, C. Presern, D. Jamison, and F. Bustreo. 2014. Advancing social and economic development by investing in women’s and children’s health: A new global investment framework. The Lancet 383(9925):1333-1354.

Sturchio, J. L., and A. Goel. 2012. The private-sector role in public health: Reflections on the new global architecture in health. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Sturchio, J. L., and M. Schneider. 2017. Strengthening partnerships with the private sector: Supporting universal coverage of women’s and family health. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Tate, J. E., A. H. Burton, C. Boschi-Pinto, A. D. Steele, J. Duque, and U. D. Parashar. 2012. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases 12(2):136-141.

UN (United Nations). 2015. Addis Ababa action agenda of the third international conference at financing for development. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: United Nations.

UN Integrated Implementation Framework. n.d. Debt2Health. http://iif.un.org/content/debt2health (accessed March 16, 2017).

USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development). 2016. Mobilize domestic resources for health. https://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do/global-health/health-systems/goals/mobilize-domestic-resources-health (accessed April 24, 2017).

USAID. 2017. Development innovation ventures. https://www.usaid.gov/div (accessed March 16, 2017).

Waning, B., M. Kyle, E. Diedrichsen, L. Soucy, J. Hochstadt, T. Bärnighausen, and S. Moon. 2010. Intervening in global markets to improve access to HIV/AIDS treatment: An analysis of international policies and the dynamics of global antiretroviral medicines markets. Globalization and Health 6:9.

WEF (World Economic Forum). 2006. Global health initiative: Public-private partnership case example. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. The smallpox eradication campaign—SEP (1966-1980). http://www.who.int/features/2010/smallpox/en (accessed February 14, 2017).

WHO. 2017. Global public goods for health (GPGH). http://www.who.int/trade/resource/GPGH/en (accessed February 13, 2017).

World Bank. 2014. A smarter approach to delivering more and better reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health services. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2016. Pandemic emergency facility: Frequently asked questions. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/pandemics/brief/pandemic-emergency-facility-frequently-askedquestions (accessed March 17, 2017).