2

Investing in Global Health for America

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”

—John Muir

Over the past several decades, there has been marked progress in the alleviation of poverty and suffering. Life expectancy has risen worldwide, child survival has almost doubled, and the global community has turned the tide of deadly diseases. Yet, at the same time, the spread of urbanization, the speed of global travel and the movement of goods, increased consumption of animal protein, and climate change have facilitated the emergence and rapid spread of infectious diseases, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), pandemic influenza, Ebola virus, and Zika virus (Burkle, 2017). Additionally, drought, famine, war, and country conflicts have led to international humanitarian and refugee crises, creating unstable conditions in which radical ideologies and diseases can thrive (WEF, 2017). Historically, the United States has made major investments in global platforms and initiatives that have largely enabled containment of threats such as infectious diseases before they reach the United States and promoted global security, stability, and prosperity. Examples of such investments include human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) treatment, infectious disease surveillance and response, vaccine development, and maternal and child health improvement. These investments have also benefited U.S. businesses both in terms of enabling a growing base of healthy, prosperous customers, as well as ensuring the safety of U.S. multinational operations around the world, and facilitated the continued leadership of the United States in research and development in biomedical sciences and technologies (Daschle and Frist, 2015; Lima et al., 2013; Wagner et al., 2015).

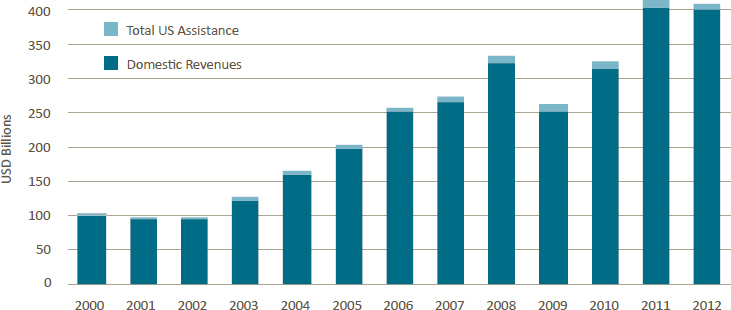

However, competing priorities and demands on government funding create an imperative for the United States to examine the economic benefits of investments in global health for the economy, national security, innovation, and global standing. Shifts in global economies and private-sector engagement are changing the nature of these investments (Sturchio and Goel, 2012). In the past decade, many countries that have historically received foreign aid have begun experiencing economic growth and rising middle classes. This growth has allowed traditional aid recipient countries to expand their tax base. In fact, through taxation and mobilization of domestic resources, the funds collected between 2000 and 2014 in sub-Saharan Africa rose from $100 billion to $461 billion (Runde and Savoy, 2016). The growth of many multinational businesses has also forced business executives to adopt a more global perspective regarding long-term planning, workforce development, and safety. As a country plans for both its own future and that of the world, a prudent step is to assess current investments and adapt them to reflect these global changes. Although great progress has been achieved toward the completion of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)1 since their launch in 2000, there are still unfinished agendas. The transition in 2016 to the multidisciplinary Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) illustrates the continued commitment to end poverty, save the planet, and ensure prosperity for all. There is a chance to save the lives of millions of children and adults by investing in global health over the next 20 years (Jamison et al., 2013). Furthermore, investing in health has benefits beyond saving lives and is considered to have made the largest contribution to sustainable development (Jamison et al., 2016). According to the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health, achieving a grand convergence in global health by 20352—reducing infectious disease, maternal, and child deaths down to universally low levels within a generation—is estimated to produce benefits that would exceed the costs

___________________

1 The Millennium Development Goals are “The world’s time-bound and quantified targets for addressing extreme poverty in its many dimensions-income poverty, hunger, disease, lack of adequate shelter, and exclusion-while promoting gender equality, education, and environmental sustainability. They are also basic human rights-the rights of each person on the planet to health, education, shelter, and security” (Millennium Project, 2006).

2 Achieving convergence would require significant increases in health spending in low- and lower-middle-income countries—$30 billion in low-income countries and $61 billion in lower-middle-income countries in 2035. Expected economic growth, together with other sources of revenue, such as taxes on tobacco and removal of subsidies on fossil fuels, will enable low-income countries to finance most of this agenda on their own, while middle-income countries will easily be able to leverage resources domestically (Summers and Jamison, 2013).

of investment between 9 and 20 times for low- and lower-middle-income countries, respectively3 (Jamison et al., 2013; Yamey et al., 2016).

This chapter identifies the benefits of global health investment for the United States, discusses the current spending of the United States on global health programs, and explores opportunities for future investment based on trends affecting health such as globalization, the SDG agenda, and private-sector involvement.

WHY GLOBAL HEALTH FUNDING PROTECTS U.S. INTERESTS

There will likely always be a demand for U.S. support when it comes to disaster relief and humanitarian efforts because the U.S. response system excels at logistics and operations. But disaster response must be complemented by investment in programs and countries during steady state times—acknowledging the public health mantra of “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Money spent on improvements to infrastructure, workforce training, and response systems—both in the United States and abroad—protects Americans from threats such as emerging infectious diseases or bioterror attacks. Such investments help to build everyday resilience so communities are prepared for all types of disasters, whether they take the form of a bus crash, an active shooter event, or an Ebola outbreak. Similarly, investing in the development of countries around the world through partnerships and capacity building can help foster stable economies with sufficient opportunities for their citizens, discouraging them from feeling forced to flee their country. Stable countries with growing middle class populations are more likely to become trading partners and to purchase U.S. goods; 11 of the top 15 U.S. trading partners are former recipients of U.S. foreign assistance programs (InterAction, 2011). Moreover, beyond just trading partners, the shared burden of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) around the world is a strong justification for health and scientific partnerships that can lead to shared solutions to common problems. Many aid-recipient countries suffer from similar health burdens to those in the United States, such as hypertension, cancer, poor maternal health, or depression.

The reasons for U.S. investment in global health are numerous, but with so many competing priorities, limited resources dictate prioritization. However, providing foreign assistance through overseas development aid (ODA), and acting in the best interest of the United States can often be

___________________

3 This estimate was found using a full income approach, where income growth plus the value of life years gained in that period results in a change in a country’s full income over a time period. This accounts for the omission of reduced mortality risk in typical gross domestic product (GDP) measures to give a more complete picture (Summers and Jamison, 2013).

accomplished simultaneously. The recent change in administration in the U.S. political system is a chance to pause and take a more holistic view of each of the elements of current global health investments as part of an interconnected system. In this process, it is critical to consider the longer-term consequences that will arise from near-term decisions on the future of investments in global health.

EXISTING U.S. GLOBAL HEALTH SPENDING

U.S. funding for global health grew from $1.7 billion in 2000 to $8.47 billion in 2009 (Salaam-Blyther, 2013), increasing on an average of 19.53 percent per year. The 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report U.S. Commitment to Global Health called for an increase in the budget for global health programs, urging the U.S. government to invest $15 billion annually in global health by 2012, of which $13 billion should be directed toward the MDGs and $2 billion toward NCDs and injuries. Unfortunately, the timing of the Great Recession of 2008 likely impacted this call for action, and while funding did increase slightly, annual U.S. global health funding continued to hover around $10 billion from 2009 to 2015 (Valentine et al., 2016), with approximately $6.5 billion dedicated to global HIV/AIDS efforts (KFF, 2012).4 Compared to prior years, annual growth in global health spending has only been 1.6 percent between 2010 and 2016 (IHME, 2017).

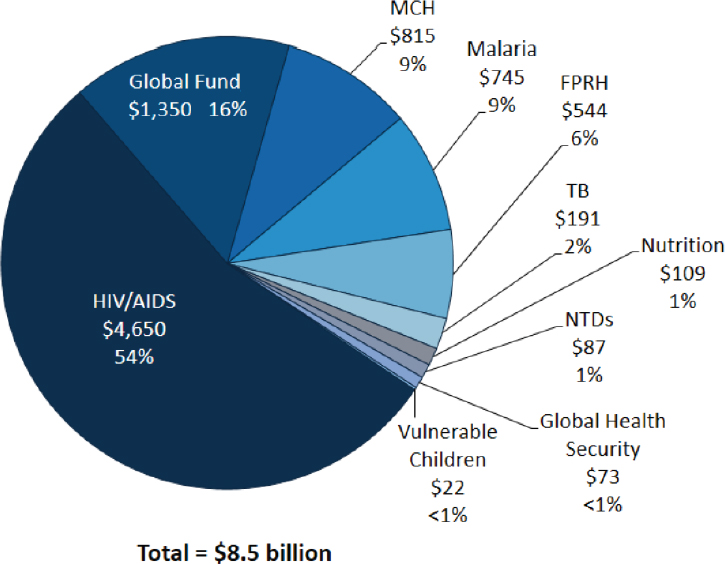

The most recent budget request from President Obama for FY2017 included $10.3 billion in total funding for global health programs (Valentine et al., 2016). According to Valentine and colleagues, within the international affairs budget, most of the global health funding ($8.6 billion) in the FY2017 request is provided through the global health programs (GHP) account at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Department of State, including funding for The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the President’s Malaria Initiative. For a full breakdown of the GHP account, which does not include global health money spent by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) or the U.S. Department of Defense, see Figure 2-1. In its analysis of the global health budget, the Kaiser Family Foundation noted that Congress has approved higher funding levels for global health than those in the President’s budget request for each of the past 4 fiscal years. However, whether that trend will continue is unclear.

___________________

4 Appropriated U.S. funding for global health between 2009 and 2016 fluctuated: $8.46 billion in 2009, $9.016 billion in 2010, $8.86 billion in 2011 (Salaam-Blyther, 2013), $9.8 billion in 2012, $9.6 billion in 2013, $10.2 billion in 2014, $10.2 billion in 2015, and 10.2 billion in 2016 (Valentine et al., 2016).

NOTE: FPRH = family planning and reproductive health, HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, MCH = maternal and child health, NTD = neglected tropical disease, TB = tuberculosis.

SOURCE: Valentine, A., A. Wexler, and J. Kates. The U.S. global health budget: Analysis of the fiscal year 2017 budget request. (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 22, 2016) (http://kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/the-u-s-global-health-budget-analysis-of-the-fiscal-year-2017-budget-request [accessed January 26, 2017]).

Table 2-1 illustrates global health spending by U.S. government agencies in the four focus areas of this report: emerging infectious diseases; HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), and malaria; maternal and child health; and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancers.

Perceptions of U.S. Global Health Spending

The American public approves of the United States taking a leading or major role in solving international problems, as revealed by a 2016 Kaiser Family Foundation survey of Americans on the United States’s role in global

TABLE 2-1 U.S. Global Health Budgeted Spending on Priority Areas in 2016 (in $ millions)

| Agency | Emerging Infectious Diseases | HIV/AIDS, TB, and Malaria | Maternal and Child Health* | Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USAID | $50.00 | $1,026.00 | $1,421.00 | ** | $2,497.00 |

| U.S. Department of State | $4,320.00 | $165.00 | $4,485.00 | ||

| CDC | $601.50 | $128.40 | $219.00 | ** | $948.90 |

| FDA | $129.50 | — | $129.50 | ||

| U.S. Department of Defense | $712.20 | $13.30 | — | $725.50 | |

| NIH | $1,848.00 | $602.10 | — | $23.01 | $2,450.10 |

| BARDA | $522.00 | — | — | — | $522.00 |

| Total | $3,863.20 | $6,089.80 | $1,805.00 | $23.01*** | $11,758.00 |

NOTE: BARDA = Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; NIH = National Institutes of Health; TB = tuberculosis; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development.

* Budget estimates for Maternal and Child Health incorporates program areas of “Maternal and Child Health,” “Nutrition,” “Family Planning,” and “Vulnerable Children.”

** Cardiovascular disease (CVD) funding within USAID is folded into broader health systems strengthening projects, so itemized expenditures could not be identified. For CVD programs within CDC, philanthropic funding is used.

*** CVD and cancer funding from the NIH are identified as global grants provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute.

SOURCES: Boddie et al., 2015; KFF, 2016; NIH, 2017.

health (Hamel et al., 2016). Striking though, is that half of Americans think the United States is spending too much on foreign aid, until they learn that foreign aid spending is just 1 percent of the budget (Hamel et al., 2016). Global health spending, specifically, was only about 0.26 percent5 of the budget in 2016. On average, survey participants estimated foreign aid spending at 31 percent of the budget (Hamel et al., 2016). After being informed of true foreign aid expenditures, “7 in 10 Americans believe that the current level of U.S. foreign spending on health is too little or about right” (Hamel et al., 2016). While the United States contributes greatly

___________________

5 Global health spending as a percent of the budget was calculated by using 2016 enacted global health funding ($10.2 billion) from Valentine et al. (2016) and total spending ($3.9 trillion) from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO, 2017).

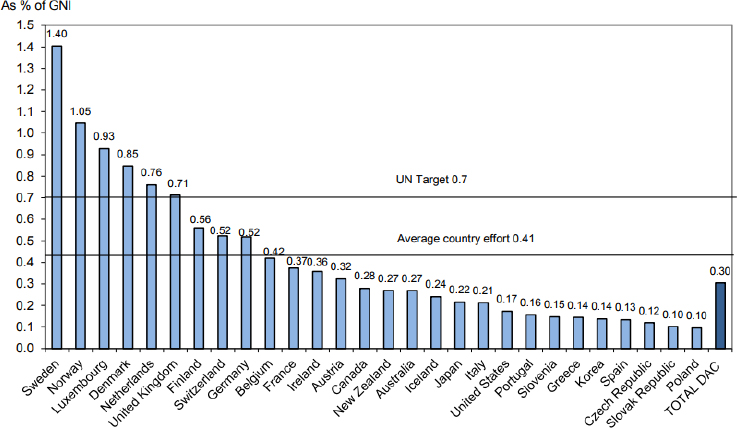

NOTE: DAC = Development Assistance Committee; GNI = gross national income; ODA = overseas development aid; UN = United Nations.

SOURCE: https://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/ODA-2015-complete-data-tables.pdf (accessed January 12, 2017).

to global aid, other donor countries are just as critical to ensuring robust development assistance in health across the globe. In fact, the United States actually contributes a lower percentage of its gross national income (GNI)6 than other high-income countries, with ODA at only 0.17 percent of GNI for the United States—below the levels of other high-income countries such as Germany, Sweden, or the United Kingdom, and well below the United Nations target of 0.7 (see Figure 2-2).

Additionally, 75 percent of Americans surveyed think the United States should give money to multilateral health organizations, such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi); the United Nations; and the World Health Organization (WHO), to improve health in other countries. These findings indicate that there is broad recognition of the advantages of leveraging the different strengths of these organizations to complement the United States’ strength as a bilateral donor (Hamel et al., 2016). As the role of foreign assistance in global health

___________________

6 Gross national income is the sum of a country’s gross domestic product plus net income received from overseas (OECD, 2016).

continues to shift in the coming years, it will be essential to consider the importance of other national governments and global players as partners in providing development and health aid, and the potential of synergized efforts toward shared global goals.

A CHANGING WORLD: EFFECTS OF GLOBALIZATION

In 2013, Julio Frenk and Suerie Moon argued that “globalization has intensified cross-border health threats, leading to a situation of health interdependence—the notion that no nation or organization is able to address singlehandedly the health threats it faces but instead must rely to some degree on others to mount an effective response” (Frenk and Moon, 2013, p. 936). In 2017, this societal interconnectedness, stemming largely from travel and trade, is fully apparent and shows no signs of reversal. Globalization and trade have cut poverty and global inequality, and have narrowed the gap between emerging economies and those of wealthy countries (WEF, 2017). Yet, the numerous advancements owed to globalization paradoxically pose threats to the security, well-being, and economic viability of all countries. For example, most of the food Americans eat each day comes from other parts of the world, making food defense and the prevention of foodborne illnesses a primary concern for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Many American businesses and their supply chains now depend on workers in foreign countries. Consequently, disease outbreaks, disasters, and poor health can diminish workforce capacity and harm business. Furthermore, industrialization often has negative effects on the environment, with mortality risk from air pollution in some locations being comparable to that of obesity (Pope et al., 2002). However, discussed in more detail in the section below, globalization also presents many opportunities for health, stemming in part from the increase in global communication and access to goods, as well as from the broader cross-disciplinary agendas that have emerged from a diverse network of global discussions.

Leveraging Globalization for Improved Global Health

Despite the increase in risks of food security, air pollution, and infectious disease outbreaks, globalization has driven innovation for the health and business sectors. Increased international trade leads to global competition, which improves the quality of products and enhances the focus on the customers, creating markets in previously inaccessible places. Similarly, sharing data and study results across countries and regions, aided by advancements in digital technology, can accelerate the elimination and eradication of global diseases and contribute to new solutions and health improvements. In November 2016, a Chinese group became the first to in-

ject a person with cells that contained edited genes using the groundbreaking CRISPR-Cas9 technique (Cyranoski, 2016). This novel technology has the potential to revolutionize the treatment of different types of cancers, and competition between countries is expected to further fuel progress, similar to the race to the moon.

The United States is likely to benefit from such innovations that address pressing health challenges, beyond the race to master gene editing. Average body mass index and rates of homicide and child and maternal mortality are higher in the United States than in any other high-income country (Kontis et al., 2017). Moreover, life expectancy for Americans is projected to stagnate in coming years. There are opportunities to learn from other countries in order to reverse these trends; global health actors often solve problems in resource-constrained environments, so the solutions are locally appropriate and fiscally sustainable. The concept of “frugal innovation” has recently been embraced by many business leaders as they expand globally, and see resource constraints as an opportunity instead of a liability, resulting in attempts to embed frugality into the company’s fundamental structure (Radjou and Prabhu, 2014). This new way of thinking could provide many opportunities for applying global health lessons to challenges faced in the United States. For example, the mobile phone–based service m-Pesa has solved the problem of limited bank account access to help Kenyans make payments through mobile phones (CBS News, 2015), which has seen extraordinary use and success since its creation. The concept has recently been specifically applied in a health context through a new program called M-Tiba that helps customers set aside money for health care needs, similar to how a health savings account works (PharmAccess Foundation, 2015). This could be adapted to certain health payment contexts in the United States to make health care payments more user-friendly. On a broader scale, the organization Global to Local, founded in 2010 in King County, Washington, identifies strategies that have been proven effective in other countries and applies them to some of King County’s most diverse, underserved populations (Global to Local, 2013). Additionally, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation created a grant program in 2015 that funds organizations to gather evidence from other countries to improve community participation and decision making in local health systems, and then bring and adapt these findings to United States (RWJF, 2015). Globalization presents the United States with many opportunities to be at the forefront of global health, with an eye for bidirectional information flow and lessons learned.

Sustainable Development Goals

Improvements in health outcomes cannot be achieved by the health sector alone. This is one of the key lessons learned through the past decade

of global health efforts and progress, including the recent outbreaks of Ebola and Zika. Health is the common denominator woven through sectors such as energy, transportation, and agriculture, and only through a multidisciplinary “health in all policies” approach can there be sustainable progress toward global health goals. Reflecting the interdependence of sectors and the implications for future development, the SDGs were put forward on January 1, 2016, to supersede the MDGs ending in 2015 as a nonbinding international agreement to harmonize the three interconnected elements of economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental protection needed to promote sustainable development (UN, 2016). While the SDGs built on the MDGs created in 2000, this new era of international cooperation shifts the vision and goals beyond those simply focused on health, and toward improving the environment, energy, economic growth, and social justice.

With 17 goals and 169 targets, the Sustainable Development Agenda is too large for any one entity to successfully address and requires a multisectoral effort. To ensure success, government bodies, along with financial institutions, capital markets, and private companies, will need to be engaged in bringing the Sustainable Development Agenda to fruition. Blending funds from donor organizations, governments, and private debt and equity offers the best chance for achieving these lofty and critical development goals (Nathan, 2017). Moreover, disruptive innovation and new methods of engagement and investment will be necessary to deliver on the development agenda. But a framework for operations is lacking; although the global economy is predicted to grow to almost $100 trillion by 2021, the delivery system of goods and services is outdated and it is coming up short both in terms of protecting the planet and protecting positive social outcomes for those in need (Kharas and McArthur, 2017). Considering these factors, and the positive and negative health effects of increasing globalization, the United States must base its efforts on multidisciplinary collaboration and implementation to continue to be a leader in global health for the next decade.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE: HOW TO BETTER INVEST U.S. FUNDS

The United States has an opportunity to think more creatively about the methods and mechanisms used to finance global health efforts, particularly as greater emphasis is placed on leveraging funding from other governments and increasing engagement of private financing. A number of approaches can be considered for optimizing limited U.S. government resources to achieve the global health goals, thereby ensuring a safe homeland and a strong trade network. In 2014, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Com-

mittee reported that 17 percent of U.S. foreign aid was provided through multilateral institutions, while 83 percent was provided bilaterally (Nelson, 2015). While this trend is similar to the global allocation of resources, some donor governments conversely prefer multilateral channels. For example Sweden directed an average of 60 percent of its development assistance for health toward multilateral channels between 2010 and 2015 (Yamey et al., 2016). Congress will continually be faced with the question of whether to provide aid bilaterally or multilaterally, and although each option has its advantages and disadvantages, the global transitions under way should inform this decision. Bilateral aid gives donors more control over how their money is spent, and it allows donor countries to align development assistance with broader strategic foreign policy objectives. Conversely, multilateral channels can sometimes achieve more impact—especially in areas where problems cannot be solved by any one country alone—because of their broad reach and networks. Additionally, the methods and sources of funding for global health projects have begun to shift with the growth of middle-income countries and a burgeoning middle class, allowing greater capacity to mobilize domestic resources. Finally, the growing involvement of the private sector in health and development can be a sustainable prospect for partnership and investing in global health, which offers governments a chance to do more with current spending.

Global Public Goods

Although traditional development assistance for health (DAH) has been successful in the last several decades, in part because of large flows of philanthropic dollars, there is no room for complacency. Owing to the increasingly globalized nature of health threats, economic growth in aid-recipient countries, and the growing need of a value-for-money approach, many argue that the allocation of DAH should shift more toward support of global goods and less toward support of local- or country-specific functions. In fact, the Center for Global Development’s (CGD’s) White House and the World Report for 2016 stated that in the present changing landscape, government revenues—as well as remittances and foreign direct investment in countries—far exceed foreign aid in all but the poorest countries (Birdsall and Leo, 2015) (see Figure 2-3). Instead of supporting countries or their programs directly, donor governments can support efficient and effective multilateral organizations, which can shift their role to catalyze new ideas, crowd-in investment,7 and promote global public goods.

___________________

7 Crowding-in is an economic principle in which private investment increases as debt-financed government spending increases. This is caused by government spending boosting the demand for goods, which in turn increases private demand for new output sources.

NOTES: Aid is defined as development assistance and other official flows reported to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee. World Bank aid figures include both concessional and non-concessional commitments by the International Development Association and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. USD = U.S. dollars.

SOURCES: Birdsall and Leo, 2015, and Center for Global Development (CGD), using data from the International Monetary Fund and the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Providing aid through multilateral channels allows for pooling resources, increasing purchasing power, dividing the burden, and cost sharing by donors, as well as greater coordination and aid effectiveness at the country level (Nelson, 2015).

Similarly, the World Bank and other multilateral development banks (MDBs) have typically only participated in global health in an ad hoc fashion, through provision of emergency financing during various crises in recent years. Yet, they are also uniquely positioned to meet current demands for global public goods, and through a shift in purpose, MDBs could expand their missions to encompass leadership on these issues that require a global shareholder base to respond collectively (Birdsall and Morris, 2016). In fact, a high-level panel on the future of multilateral development banking recommended that the World Bank promote global public goods critical to development as its major priority. This would be achieved through the creation of a new fund with a separate governance structure set up to disburse $10 billion annually in grant resources toward programs that cannot be easily structured as country operations (Birdsall and Morris, 2016). Thus, there are important roles for different actors, and through an overarching examination, donor countries, recipient governments, regional

MDBs, and the World Bank can identify strengths and weaknesses of different approaches.

In addition to directing funding toward multilateral channels, donor governments can help countries increase domestic financing, or domestic resource mobilization (DRM). These methodological considerations will be important to examine as the next administration reviews the current U.S. commitment toward unfished agendas such as communicable diseases including HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria, and long-term investments in maternal and child health.

Domestic Resource Mobilization

Recent growth projections from the International Monetary Fund show an increase of 3.5 percent globally in 2017, slightly lower than previous estimates but still showing a recovery trend worldwide. Emerging market and developing economies are estimated to be slightly higher, with 4.6 percent growth in 2017 (IMF, 2016). This gross domestic product (GDP) growth is expected to continue in coming years, which will provide further support for greater DRM. Coupled with the use of sound fiscal policies, GDP growth will result in a large portion of countries graduating from DAH and beginning to fund health needs through their own domestic resources (Bhatt et al., 2015). Moreover, with the conclusion of the MDGs and creation of the SDGs in 2016, the focus is now broadening from reducing infectious disease and child mortality to the more challenging, cross-disciplinary goals of strengthening health systems and collaboration across sectors. With these trends in mind, many donors are working to support recipient governments as they transition health programs from DAH to DRM. This also reflects a shift toward even greater country ownership of their own health priorities and programs, which will inevitably translate into long-term benefits for citizens of recipient countries as they tailor the programs to their specific needs. However, many low-income and fragile-state countries will still depend on traditional sources of humanitarian aid and development assistance to support their health programs, and continued support of these programs will be critical to ensure their progress is not lost.

While this transition to DRM occurs, more DAH can be directed toward the global functions and public goods of global health. Multilateral institutions, such as the Global Fund and Gavi, are well positioned to deliver great return on investment. Directing more money toward these institutions pools global resources and leverages economies of scale that can be much more responsive to global health needs. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) may also stand to benefit from increased fund allocation to multilateral institutions, because such countries cannot independently produce the global public goods that those institutions can, such as research

and development, knowledge sharing, market shaping, and management of cross-border externalities (Schäferhoff et al., 2015). Importantly, pursuing these elements of global public goods will be advantageous to all countries.

Leveraging the Private Sector

In addition to increasing levels of DRM with partner countries, the private sector will be a critical partner in this next stage of global health and development. An article from the 2017 World Economic Forum annual meeting argued that advancing the cross-sectoral SDGs is a business imperative and transformational change should be undertaken from an ecosystem perspective, explaining “the longevity of companies the world over is predicated on the increased access and usage of financial services by those at the bottom of the pyramid” (Nathan, 2017). The U.S. government has begun to do this in a more strategic manner, through partnerships in other sectors such as Power Africa or Feed the Future within USAID. For example, Power Africa aims to crowd-in private energy partners in LMICs and, since its inception in 2013, now has more than 130 companies involved with a projected investment of approximately $40 billion. However, through this partnership and private-sector–focused model, it has kept direct costs to the agency to only $76 million for FY2016.8Chapter 8 discusses financing models in more detail, but to emphasize the importance, the committee asks the reader to truly consider throughout the report, how to maximize public, private, and social sector dollars to spur economic growth and build stronger communities globally (Nathan, 2017).

THE UNITED STATES AS A GLOBAL CITIZEN

As many common global health challenges have coalesced over the past decade, including the growing burden of NCDs and potentially pandemic infectious disease outbreaks, several international agreements have been put into effect, committing political efforts and support toward improving health and life for all. As a long-time leader within the global community, the United States is a signatory on these agreements, such as the International Health Regulations (2005), the SDGs, and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. Whether constituted as global action plans, frameworks, goals, or regulations, these agreements further emphasize the need and motivation for the global community to come together to advance the health and well-being of each nation’s citizens. It should be the continued duty of the United States to both follow and support these global, forward-looking, collaborative efforts.

___________________

8 Personal communication with Matt Rees, Power Africa, November 10, 2016.

REFERENCES

Bhatt, S., D. J. Weiss, E. Cameron, D. Bisanzio, B. Mappin, U. Dalrymple, K. E. Battle, C. L. Moyes, A. Henry, P. A. Eckhoff, E. A. Wenger, O. Briet, M. A. Penny, T. A. Smith, A. Bennett, J. Yukich, T. P. Eisele, J. T. Griffin, C. A. Fergus, M. Lynch, F. Lindgren, J. M. Cohen, C. L. J. Murray, D. L. Smith, S. I. Hay, R. E. Cibulskis, and P. W. Gething. 2015. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526(7572):207-211.

Birdsall, N., and B. Leo. 2015. The White House and the world: Practical proposals on global development for the next US president. Washington, DC: The Center for Global Development.

Birdsall, N., and S. Morris. 2016. Multilateral development banking for this century’s development challenges. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Boddie, C., T. K. Sell, and M. Watson. 2015. Federal funding for health security in FY2016. Health Security 13(3):186-206.

Burkle, F. M. 2017. The politics of global public health in fragile states and ungoverned territories. PLOS Currents: Disasters 1.

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2017. The federal budget in 2016: An infographic. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52408 (accessed April 20, 2017).

CBS News. 2015. Want to text money? Kenya’s been doing it for years. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/want-to-text-money-kenya-has-been-doing-it-for-years (accessed March 15, 2017).

Cyranoski, D. 2016. CRISPR gene-editing tested in a person: Trial could spark biomedical duel beteween China and U.S. Nature 539(7630).

Daschle, T., and B. Frist. 2015. The case for strategic health diplomacy: A study of PEPFAR. Washington, DC: Bipartisan Policy Center.

Frenk, J., and S. Moon 2013. Governance challenges in global health. New England Journal of Medicine 368(10):936-942.

Global to Local. 2013. Global to Local: About us. http://www.globaltolocal.org/overview (accessed January 26, 2017).

Hamel, L., A. Kirzinger, and M. Brodie. 2016. 2016 survey of Americans on the U.S. role in global health. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

IHME (Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation). 2017. Financing Global Health 2016: Development Assistance, Public and Private Health Spending for the Pursuit of Universal Health Coverage. Seattle, WA: IHME.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2016. World economic outlook: Too slow for too long. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

InterAction. 2011. Choose to invest in foreign assistance. Washington, DC: InterAction. https://www.interaction.org/sites/default/files/4857/ChooseToInvest_booklet_Complete.pdf (accessed March 10, 2017).

Jamison, D., L. Summers, G. Alleyne, K. Arrow, S. Berkeley, A. Binagwaho, F. Bustreo, D. Evans, R. Feachern, J. Frenk, G. Ghosh, S. Goldie, Y. Guo, S. Gupta, R. Horton, M. Kruk, A. Mahmoud, L. Mohohlo, M. Ncube, A. Pablos-Mendez, S. Reddy, H. Saxenian, A. Soucat, K. Ulltveit-Moe, and G. Yamey. 2013. Global health 2035: A world converging within a generation. The Lancet 382:1898-1955.

Jamison, D., Y. Yamey, N. Beyeler., and H. Wadge. 2016. Investing in Health: The Economic Case. Doha, Qatar: World Innovation Summit for Health.

KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). 2012. U.S. federal funding for HIV/AIDS: The President’s FY2013 budget request. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation.

KFF. 2016. U.S. global health budget tracker. http://kff.org/interactive/budget-tracker/landing (accessed January 26, 2017).

Kharas, H., and J. W. McArthur. 2017. We need to reset the global operating system to achieve the SDGs. Here’s how. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/we-need-to-upgrade-the-sustainable-development-goals-here-s-how (accessed February 14, 2017).

Kontis, V., J. E. Bennett, C. D. Mathers, G. Li, K. Foreman, and M. Ezzati. 2017. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: Projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. The Lancet 389(10076):1323-1335.

Lima, V. D., R. Granich, P. Phillips, B. Williams, and J. S. G. Montaner. 2013. Potential impact of The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief on the tuberculosis/HIV coepidemic in selected sub-Saharan African countries. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 208(12):2075-2084.

Millennium Project. 2006. What they are. Washington, D.C.: The United Nations Millennium Project. http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/goals (accessed March 10, 2017).

Nathan, T. 2017. 5 ways to make blended finance work. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/ways-to-make-blended-finance-work (accessed December 15, 2016).

Nelson, R. M. 2015. Multilateral development banks: Overview and issues for Congress. CRS Report No. 7-5700. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2017. NIH reporter. https://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter_summary.cfm#tab2 (accessed February 8, 2017).

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2015. Final official development assistance figures in 2014. Washington, DC: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

OECD. 2016. Gross national income. https://data.oecd.org/natincome/gross-national-income.htm (accessed April 20, 2017).

PharmAccess Foundation. 2015. M-Tiba is truly leapfrogging healthcare in Kenya. PharmAccess Foundation, December 15.

Pope III, C. A., R. T. Burnett, M. J. Thun, E. E. Calle, D. Krewski, K. Ito, and G. D. Thurston. 2002. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA 287(9):1132-1141.

Radjou, N., and J. Prabhu. 2014. What frugal innovaters do. Harvard Business Review, December 10. https://hbr.org/2014/12/what-frugal-innovators-do (accessed March 15, 2017).

Runde, D., and C. Savoy. 2016. Domestic revenue mobilization: Tax system reform. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

RWJF (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation). 2015. Studying promising global practices in community participation in health systems to advance adaptation in the United States. http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/grants/2015/11/studying-promising-global-practices-incommunity-participation-i.html (accessed March 7, 2017).

Salaam-Blyther, T. 2013. U.S. global health assistance: Background issues for the 113th Congress. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Schäferhoff, M., S. Fewer, J. Kraus, E. Richter, L. H. Summers, J. Sundewall, G. Yamey, and D. T. Jamison. 2015. How much donor financing for health is channelled to global versus country-specific aid functions? The Lancet 386(10011):2436-2441.

Sturchio, J. L., and A. Goel. 2012. The private-sector role in public health: Reflections on the new global architecture in health. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Summers, L., and D. Jamison. 2013. Policy brief #2: The returns to investing in health. The Lancet.

UN (United Nations). 2016. The sustainable development agenda. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda (accessed January 26, 2017).

Valentine, A., A. Wexler, and J. Kates. 2016. The U.S. global health budget: Analysis of the fiscal year 2017 budget request. http://kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/the-u-s-global-health-budget-analysis-of-the-fiscal-year-2017-budget-request (accessed January 26, 2017).

Wagner, Z., J. Barofsky, and N. Sood. 2015. PEPFAR funding associated with an increase in employment among males in ten sub-Saharan African countries. Health Affairs (Millwood) 34(6):946-953.

WEF (World Economic Forum). 2017. The global risks report 2017. 12th edition. Cologny, Switzerland: World Economic Forum. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GRR17_Report_web.pdf (accesed March 10, 2017).

Yamey, G., J. Sundewall, H. Saxenian, R. Hecht, K. Jordan, M. Schäferhoff, C. Schrade, C. Deleye, M. Thomas, N. Blanchet, L. Summers, and D. Jamison. 2016. Reorienting health aid to meet post-2015 global health challenges: A case study of Sweden as a donor. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 32(1):122-146.

This page intentionally left blank.