3

Laying the Foundation for Effective Communication

“Risk communication is a bridging domain of research and practice, where the biomedical and the social and behavioral sciences come together,” said Douglas Storey, associate director at the Center for Communication Programs at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, when introducing the next section of the workshop, which discussed some of the foundational research on effective communication and decision science and examined the current state of science on understanding of risk and health-protective behaviors from both the United States and international contexts. The seven speakers who provided their insights were Baruch Fischhoff, the Howard Heinz University Professor at Carnegie Mellon University; Angie Fagerlin, inaugural chair of the Department of Population Health Sciences at the University of Utah and a research scientist at the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Center for Informatics Decision Enhancement and Surveillance; Gary Kreps, university distinguished professor and director of the Center for Health Risk Communication at George Mason University; Noel Brewer, professor of health behavior at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Rajiv Rimal, professor and chair of the Department of Prevention and Community Health at the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health; Monique Turner, associate professor and assistant dean at the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health; and Jeff Niederdeppe, associate professor of communication at Cornell University.

THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF SUCCESSFUL COMMUNICATION CAPACITY

Fischhoff listed five important questions to answer when thinking about building communication capacity to deal with infectious disease threats:

- What information do we need to communicate about infectious diseases?

- What science do we need to acquire that information?

- What people do we need to apply that science?

- What organizational structures do we need to coordinate those people?

- What commitments will it take to make that happen?

The information to communicate to the public could include how severe a particular disease is, how transmissible it is, where it is found, how effective various protective measures are, and how practical those protective measures are given personal and family circumstances. The public also needs to know which sources of information to trust and when news is real or fake, Fischhoff added. The public health community has its own information needs, such as the beliefs and concerns of the populations they serve, what resources they have, whom they prefer to get their information from and what their trusted information channels are, and what their experiences have been in past situations.

The science of communication design, said Fischhoff, is well developed, and starts with an analysis that identifies the facts relevant to the choices people face and then proceeds to descriptive research to determine what people believe and want. The results from those activities inform the design of measures to fill the critical information gaps, and evaluation then measures whether the resulting intervention works. This process is repeated as necessary, he explained, given that no intervention works best at its first iteration. “The science base for learning about the public’s needs is vast,” said Fischhoff, who noted that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have contributed greatly to that science base (Fischhoff and Scheufele, 2013a,b; NRC, 1989). “The question is really about capacity building or how to use that science base,” he said.

Deriving the information the public needs to know often involves integrating knowledge from diverse sources and helping experts synthesize that information in the most authoritative yet understandable manner possible (Morgan, 2014). One common approach to eliciting information from experts on the uncertainty of something happening, Fischhoff explained, is to ask them the same question two different ways to test whether their judgment is sufficiently coherent (Bruine De Bruin et al., 2006). He noted

that in 2014 the National Academies held two workshops on characterizing and communicating uncertainty as it pertains to the risks and benefits of pharmaceuticals (IOM, 2014) and gain-of-function research (IOM and NRC, 2015).

Applying the science and executing a plan require involving people with a range of expertise, said Fischhoff. Domain specialists need to provide information on all aspects of a disease and any control mechanisms, he explained, and analysts then need to reduce the “firehose of information” from the domain experts into a form relevant to the different intended audiences. Experts from the social sciences, behavioral sciences, and humanities provide guidance on the needs of those intended audiences so the content experts can address those audiences with some understanding of who they are. Application professions train the content experts, prepare materials appropriate for specific audiences, and oversee the plan. A coordination mechanism is needed, Fischhoff said, so that everyone involved can provide input at each step, but in the end, the final authority rests with the experts in each of these domains.

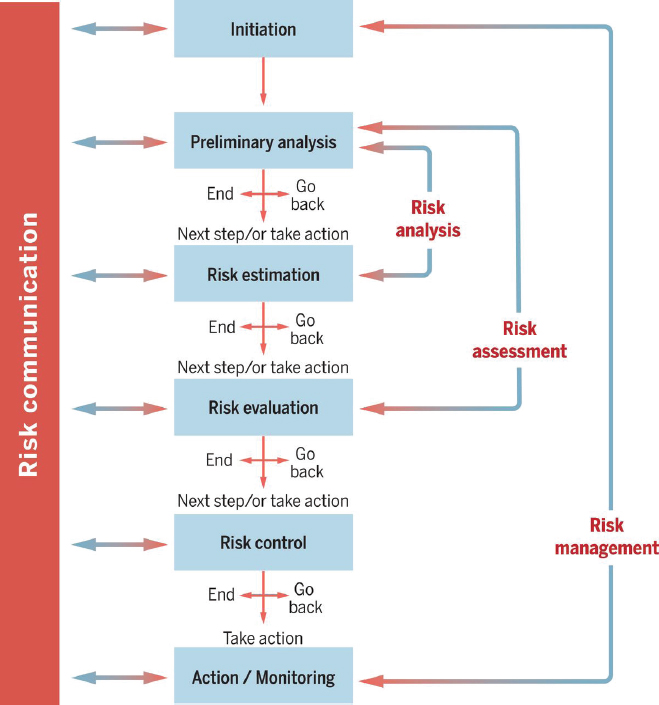

With regard to the organizational structures required to coordinate all this activity, Fischhoff said structures are needed to connect professionals with other professionals within and outside their own disciplines, as well as to coordinate interactions within the public audience. Two key points here, he said, are that the public must be consulted throughout any communication effort and findings need to be communicated to all stakeholders (IOM, 1999). He referred to a Canadian process for risk communication (Fischhoff, 2015) that solicits audience feedback between every stage of developing that effort (see Figure 3-1) as an example that could be an effective organizational structure.

Evidence and preparation, Fischhoff highlighted, are two commitments needed to take advantage of the science, assemble the public, and organize them to address the situation. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a report in 2011 that discussed the commitment to evidence in risk communication (Fischhoff et al., 2011). Each chapter in this FDA report summarizes the science of a particular topic, such as health literacy, shared decision making, and practitioner perspectives; offers best guesses about the practical implications of the science; and shows how to evaluate communications for little or no money or for a larger amount of money commensurate with the personal, organizational, and political stakes riding on effective communication.

A commitment to preparation, Fischhoff explained, requires developing consultative relationships with the public and among professions and leaving enough time to make use of those relationships. He added a commitment to preparation also requires having pretested communication modules for specific classes of information and resources for expert elicitation, mes-

SOURCES: Fischhoff presentation, December 13, 2016; reprinted with permission, from Fischhoff (2015). Copyright 2015 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.

sage testing, and tracking public response. Forcing a project out the door simply because of a deadline most likely means that something will not have been done correctly. Fortunately, said Fischhoff, infectious disease threats have a particular set of characteristics that a modifiable and reusable structure can address without having to start from scratch for each new threat.

FDA has developed a strategic plan for risk communication (FDA Risk Communication Advisory Committee, 2009) that attempts to balance moving too early and raising a needless alarm and moving too late and missing an opportunity to reduce mortality and morbidity. FDA, said Fischhoff, has recognized that it does not know the public audience very well. This

type of document addresses building baseline capacity within an organization, but a need also exists to prepare surge capacity that brings in external resources, particularly people who are not on the front lines at all times and who have time to think about these types of issues. As an example of surge capacity, Fischhoff mentioned the Applied Psychology Unit at the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council, which was a collection of external experts who conducted behavioral research and stood ready to help British agencies and stakeholders.

Summarizing his presentation, Fischhoff said the science of communicating well about infectious diseases exists and is often used effectively. Communicating well about infectious diseases, he stated, requires diverse forms of expertise and trusted relationships. He added that providing the resources and organization needed to address routine challenges and disease outbreaks requires strategic leadership.

When asked what he thought the biggest challenge to successful risk communication was, Fischhoff replied that the biggest challenge was not letting the problem get out of control. “Research suggests that you can explain most things to most people if you have not lost control of the problem,” he said. “But once the problem gets out of control, then you have other people grabbing the microphone who have other agendas and you have misinformation that gets out.” As examples of what can go wrong, he said the climate change community and nuclear power industry made the mistake of believing that their story would tell itself. Capacity building that views communications as a two-way process and includes trust-building activities can enable organizations to get out in front and stay ahead of problems, Fischhoff added.

LEARNING FROM THE DECISION SCIENCES TO DESIGN TARGETED MESSAGES

One story Fagerlin shared that McKenna did not mention in her list of inappropriate actions triggered by the West African Ebola crisis was that of a bridal shop in Akron, Ohio. This shop closed after 30 successful years because one of the nurses later diagnosed with Ebola had visited the shop in October 2014 to help her bridesmaids try on dresses. The store worked with officials to do a deep clean and reopened, but when the owner closed the store for good, she said the public thought of her store as the Ebola shop. “This is a great example of the difference between people’s feelings of risk and their actual risk, how that disconnect can affect their decision making, and the consequences that result from that decision making,” said Fagerlin.

The goal of risk communication, she said, is to have people’s perceptions and feelings of risk match the actual risk they experience. How the

public perceives the risk of influenza is another example, albeit in the other direction. In this case, said Fagerlin, many members of the public do not perceive there to be much risk; hence they do not get flu shots, even though the risk of consequences from influenza are substantial.

Many people in the public health community, when confronted with a disease, try to learn as much as possible and then try to communicate all that information to the public, she said. Fagerlin noted that the consequence of that approach—of appealing to the director instead of the mom—is providing too many details, and the typical layperson does not know which details are important. However, she added, paying attention to which details to communicate and what words to use can create quality messages that can shape the resulting emotional response to risk. For example, a study she participated in found that people felt more at risk when messages used the words “H1N1 influenza” instead of “avian flu” and were more likely to want to get the vaccine. “A two-word difference affected people’s willingness and interest to get vaccinated,” she said. This study also found that talking about the typical symptoms of influenza had a bigger impact than discussing the most severe symptoms on people’s risk perceptions and their willingness to vaccinate. One finding contrary to what many experts believe was that people want communications to be certain and to not acknowledge the uncertainty of a situation.

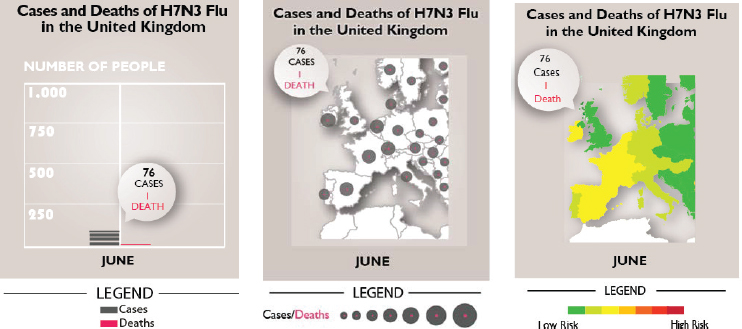

Fagerlin and her colleagues also looked at the effectiveness of three devices for communicating risk visually: a picto-trend line, a dot map, and a heat map (see Figure 3-2). The heat map and dot map were largely equivalent in their effectiveness at conveying risk, though the heat map was slightly better at increasing the people’s understanding of how many indi-

SOURCE: Fagerlin presentation, December 13, 2016.

viduals contracted influenza and died. The picto-trend line was not useful in this case, so she suggested avoiding its use.

Fagerlin noted that, of the three choices, participants in the study liked the heat map best, a key finding given that aesthetics can play a significant role in getting people to pay attention in the first place. In the social media age, when information sharing is important, people are more likely to share something they find aesthetically pleasing, she said. “As long as different approaches are equivalent in terms of knowledge, risk perception, and behavioral intentions, I think it is important that we ask people what they like and do not like so that we can communicate farther and wider,” said Fagerlin.

Persuasion can be a critical risk communication tactic for influencing behavior, but persuasion using social norms can be tricky, said Fagerlin. As an example, she explained that telling people that almost half of all American adults do not vote does not inspire people to vote. In fact, she said, it has the opposite effect because it absolves them of the guilt of not voting. The same is true for immunization: trying to inspire people by using the concept of herd immunity to get them to contribute to that common good has the opposite effect.

One promising risk communication tactic is to target messages and the media for conveying those messages to reach specific groups of people. “How we communicate should differ based on the audience that we are trying to reach,” said Fagerlin. However, in this age of informatics and social media, message targeting should be more sophisticated than basing it on broad categories such as sex, race, or ethnicity, added Fagerlin. Given that Google can pop up ads based on what someone searches for on Amazon, Fagerlin wondered how the public health community could make the same type of highly targeted connections.

Fagerlin briefly discussed message evaluation, and how many investigators, including herself, use survey measures to assess knowledge, risk perceptions, behavioral intentions, and satisfaction with messages. However, she said, surveys may not be the best approach for evaluating messages, and as an example she discussed the results of a study on the effectiveness of various public service announcements intended to get smokers to call a quit line (Falk et al., 2011). In this study, Falk and her colleagues had participants watch several professionally created television ads and asked them which would be more effective at getting people to quit smoking. A second group of participants watched the same ads while the researchers monitored the participants’ brain activity by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). When these ads ran on California television stations, the fMRI results accurately predicted which public service announcements would be the most effective; the survey results had no predictive power. Although testing every message using fMRI is not feasible, it points to the

importance of using other physiological and ecological measurements, such as how long people look at messages and how often they share them, said Fagerlin.

She noted in closing that it is imperative to think about who the audience is and to talk to that audience before launching a campaign. Using new services such as Amazon Mechanical Turk, Knowledge Networks, and Survey Sampling International, she suggested, is a relatively simple and quick means to test various strategies with intended audiences.

EVIDENCE-BASED METHODS AND EVALUATION STRATEGIES

Although he describes himself as a big believer in the power of communication to address major health problems, Kreps said many misconceptions limit its effectiveness. Perhaps the biggest misconception, he said, is that communication is easy to do well. “I think people try to come up with relatively simple, broad, encompassing, and powerful killer messages to address major complicated health issues, and sometimes they work, sometimes they do not, and they often make things worse,” said Kreps. He stressed that with infectious diseases, for which the situation can change quickly and there are many risks and issues involved, it is particularly important to communicate in ways that are most meaningful to the populations that need information and that provide them with information they can use.

Strategic, evidence-based risk communication is a critical component of a strategy to achieve that goal, said Kreps, and he encouraged the workshop participants to develop the kind of strategic communication activities described in his presentation. What happens more often than not, he said, is that well-intentioned public health communicators forge ahead with limited data on how effective messages will be at reaching their intended audience, if the audience is even paying attention to the messages, and whether the messages are influencing behavior. Instead, he added, they need to be asking the following questions before launching yet another messaging program that may or may not accomplish anything:

- What do we know about how well the programs we have developed in the past have worked and how well the programs we want to develop in the future will work?

- How effective have we been at reaching different people, and how do they respond?

- What has happened in the past that would encourage us to use similar or different strategies in the future?

- Have there been any unintended consequences from past efforts that made matters worse, such as triggering unrealistic fears?

- Have past efforts provided people with the support, encouragement, and reinforcement they need to take action or change behavior?

Above all, he said, it is important to be honest about whether anyone paid attention to past communication programs. “Much of the research shows that risk communication and public health communication in general often have extremely limited exposure,” said Kreps. “This is not the primary place that people want to focus their attention, and they often will hear some little tidbits about the danger but not a lot about the recommendations.”

One problem, he added, is that many people design risk communication programs from their own frame of reference. The messages make sense to them, they understand the information and the risk, and they are already compelled to take action. “Typically, though, the people who are designing the programs are not the ones you are trying to reach. They are not the ones that are at risk. They are not the best barometer of what works and what does not work,” said Kreps. “We need to be going out and focusing on who are the people you want to reach and what are their issues.”

It is important, then, he added, to understand how diverse audiences have responded to these programs. “One of the things that I want to talk to you about is segmenting your messages to specific at-risk populations, because the idea of one-size-fits-all does not work well with risk communication,” said Kreps. “You need to figure out who you want to communicate with, who the people are, who are most misinformed, who is at greatest risk, where they get their information, what do they need to know, what is going to work for them in their lives, in their communities, within their families, and what they can and cannot do. Once you know these things, then you can be very strategic about the ways that you communicate.”

Kreps stressed the importance of setting measurable goals and outcomes and having funds to evaluate the effectiveness of a messaging campaign. With regard to infectious diseases, which are always going to be around, he urged that evaluation should become a standard operating procedure that includes generating baseline data on what people knew and what they were doing before a program launches. Without such data, it is difficult to know if a program has met its goals. He noted, too, that many powerful social and behavioral theories explain how different types of messages influence people, how people perceive different types of messages, and how they interpret the information in those messages. These theories can provide practical insights into what type of messages and information make people want to take action and to recognize, respect, and believe different sources of information.

Three Stages of Evaluation Research

After recounting some of the many reasons he has heard public health communicators cite for why they do not do research and evaluation, such as resource and time constraints, Kreps dismissed them all by pointing out that having good data is like turning on a light. “When you are dealing with a crisis, you want to see where you are going and why you are going there,” he said. “Good data allow you to adjust, refine, and improve over time.” He also cautioned that creating a good message is hard and rarely accomplished on the first try, which again argues for the importance of ongoing evaluation. Data can also shine a light on whether the outcomes that a program achieves were worth the investment.

Formative evaluation of health communication is critical, said Kreps, as it can assess the need for a communication program. Formative evaluation can identify and segment key audiences so that tailored messages will reach the most homogeneous groups, and it includes extensive audience analysis research to understand the backgrounds, interests, communication orientations, literacy levels, and expectations of those audience segments. Formative evaluation can also identify the best channels to reach audiences and the most effective message strategies to influence those audiences.

Process evaluation, conducted during a communication campaign, tests program implementation in key settings to see how well the program is accepted and used. It also tracks initial user responses to programs to see how audience members interpret messages. “You need to evaluate how people are responding to your messages,” said Kreps. “Do they understand them? Are they paying attention to them? Are the messages influencing them? Are people doing what you want them to do or are they doing something else?” Process data, he explained, enable tracking messages, assessing their effectiveness, and refining those messages.

Kreps said he is a big believer in feedback, and he stressed the importance of building a process of getting feedback into every communication program. “We need to get people to tell us what their experiences are, what they want, what they like and do not like, and then use those data to refine our messages over time,” said Kreps. “We need to track responses to refine programs and figure out what works so that we can implement and sustain those good parts of the programs.”

Summative evaluation is the last piece of the research process, and it takes advantage of the data generated during the formative and process evaluations, explained Kreps. Summative evaluation assesses patterns of program use and overall user satisfaction with the program. It evaluates message exposure and retention and tracks changes in key outcome variables, such as learning, health behaviors, service use, and health status. Summative evaluation aims to identify the best program strategies, features,

and approaches, including building support for sustaining successful programs. Summative evaluation may also benefit from including an economic analysis of a program’s costs and benefits.

When asked to speak to some of the challenges of incorporating research into the risk communication cycle and making it an integral part of planning in decision making, Kreps said the biggest issue is that people do not realize the complexity of the research process and therefore do not figure out ahead of time how to collect the data needed for research and evaluation. One solution he and Fischhoff both recommend is for public health agencies to have at least one person on staff who is good at collecting social science data and who understands how to use them. “It has not really been a priority in the past, but I think that there is an opportunity to recruit students who are now developing expertise in this area,” said Kreps. There are many experts in academia, Fagerlin added, who would love to collaborate with public health agencies to develop ongoing data collection and analysis procedures.

Kreps noted there is a tremendous amount of archival data available from previous research and demographic studies about different populations that every researcher should access ahead of time. Doing so, he said, would allow a project to move more quickly. He also suggested that risk communication programs should be gathering more information from in-depth interviews with key informants from different communities, both to understand the needs of those communities and to build close relationships with them ahead of time. “I think if we can build those kinds of ongoing flowing data sources, we can be a lot smarter about the ways that we respond, and also be a lot more adaptive than we have been in the past,” said Kreps.

Building the Infrastructure for Data Collection

When Damien Chalaud, executive director of the World Federation of Science Journalists, questioned how to collect data in countries that have little or no infrastructure, Kreps agreed that working in the absence of resources and infrastructure is a challenge, which is why he believes it is important to build a network of people in the community who can serve as an ongoing source of data. The growth of social media and the digital environment worldwide can also be a source of data given that people can post and provide information about their experiences and provide the feedback that is critical for adjusting a message and strategy. He noted that social media posts have been a critical source of information in public health crises. Fischhoff added there is a misconception that data collection is always expensive and time consuming, when there are ways of collecting data quickly and with virtually no expense.

GOALS FOR RISK COMMUNICATION

To Brewer, risk communication is a weak intervention, something done when everything else fails. “We can do risk communication, but we should be modest about our expectations for it,” he said.

The general model for changing risky behavior is to communicate risk in a way that alters risk beliefs to trigger risk-reducing behavior, Brewer explained. One way to communicate risk, and the approach federal law requires FDA to take with new drugs, for example, is to just say it. Another approach to “just saying it” is to hold a community forum at which people gather and talk about what they know and do not know. The goal here, he said, is not to change anyone’s belief but rather to create community around the act of communication.

The context of risk communication is important, said Brewer. As an example, he cited one study in which women who tested positive for the BRCA mutation were informed about the risk of their developing breast cancer, which is slightly more than 20 percent. What these women recalled was that the risk was higher, close to 30 percent, but their perceived level of risk, that is what they actually believed, was that the risk was higher than 40 percent (Gurmankin et al., 2005). However, in a different study that he conducted with women who had early stage breast cancer, their actual, recalled, and perceived levels of risk of recurrence were approximately all the same at just above 10 percent (Brewer et al., 2012).

Changing risk beliefs—the perceived likelihood, perceived severity, fear, and anticipated regret if a decision ends badly—is hard, Brewer continued. As an example, he briefly discussed a study on risk beliefs with regard to influenza during the vaccine shortage of 2004 to 2005 (Brewer and Hallman, 2006). This study found that over half the population at a high risk of contracting influenza did not know they were at high risk and therefore did not get vaccinated, showing the importance of subjective feelings of risk compared to objective facts about risk.

Another study he conducted looked at the effect of pictorial warnings that convey the health hazards of smoking compared to the Surgeon General’s warning (Brewer et al., 2016). The pictures were far more effective than the Surgeon General’s warning at encouraging people to quit smoking, attempt to quit smoking, and successfully quit smoking, but not because it changed their perception of risk. What happened, he explained, was that the gruesome pictures stuck in people’s minds and made them afraid in a way that words did not.

If the ultimate goal is to change risky behaviors, risk communication may or may not be the best approach for doing so, said Brewer. Policy change can be a potent approach to changing behavior (Brownell and Frieden, 2009; Frieden et al., 2010), and Brewer said it may be that risk

communication may be indirectly effective by changing the support for new policies. Achieving policy support may indeed be one of the most important things we can do whether or not we change individuals’ health behaviors with risk communication, he said.

In closing, Brewer noted that risk communication is more effective when people understand the information, whether that understanding is accomplished using narratives or images. The key is to make the information personally relevant. Risk communication works best when people have an immediate or near-term course of action. It is one thing to make people fearful, said Brewer, but they also need to have information on how to respond to that fear. Finally, risk communication has a better chance of succeeding at changing behavior if it triggers self-affirmation. “What that means is that we reinforce something that is of value to the individual before we give them risk information,” said Brewer. Doing so, he explained, puts an individual in a positive frame of mind so he or she can better grasp tough information.

TRANSLATING RISK PERCEPTION INTO BEHAVIOR CHANGE

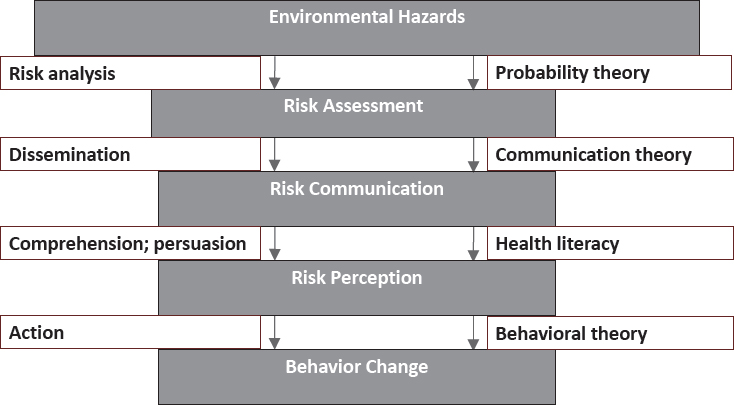

Before talking specifically about risk communication, Rimal briefly described the multistep process involved in translating environmental hazards into behavior change (see Figure 3-3). This multistep process includes

SOURCE: Rimal presentation, December 13, 2016.

risk assessment, risk communication, risk perception, and finally behavior change, and it involves applying a variety of social sciences, such as communication theory and health literacy, to the challenges at each step. Many of these steps are reciprocal, as various speakers had noted already.

One challenge for risk communication is to address the difference between the way information is intended to be received and the way it is actually received. Communication seldom occurs in a social, political, or cognitive vacuum, said Rimal, and the result is that messages are distorted. Part of the reason for that distortion is that people are good at listening to the opinions of others who think as they do because it is uncomfortable to listen to those with differing viewpoints. One way of thinking about the effects of the so-called echo chamber is to consider that cognitive bias, prior experiences, perceived losses, political beliefs, culture, and traditions may all act to refract information so that what someone sees or hears is not what they were intended to see or hear. These factors influence the way people go through the mental gymnastics that minimize or deny an objective risk. In addition, said Rimal, when people are viewing information through that refractory lens, they become further confused when learning that information is not absolute, that is, that there is a probabilistic uncertainty to the information.

In Rimal’s opinion, minimizing the refraction that occurs in risk communication requires building trust through transparency. One factor contributing to the vaccination crisis, he pointed out, is that the public perceives that the experts promoting vaccination work for pharmaceutical companies. Building trust, he said, requires being honest about what is known and unknown. Developing partnerships with the communities being served is critical, Rimal added, because it allows communities to have a say in how information is given to them and to see that their feedback is being heard.

Rimal and his colleagues have been focusing on the last step of the model he presented, the translation of risk perception into behavior change. There are many ways to measure perceived risk, he explained; one way is to consider the dichotomy between susceptibility—how much risk there is to become infected—and severity, or how horrible it would be to become infected. His research suggests that these two concepts may not always be in sync. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, people believe the consequences of becoming infected with HIV are severe, but they also believe they are not personally at risk of becoming infected. When he started working in Mali, HIV infected 18 percent of the population, but the people of Mali thought their risk was about 2 to 3 percent. Rimal suggested that minimizing the risk to that degree might be a coping mechanism to deal with the high number of deaths from AIDS that people may have seen.

Rimal noted the growing body of work showing that how people perceive risk information and what they do with that information depends on

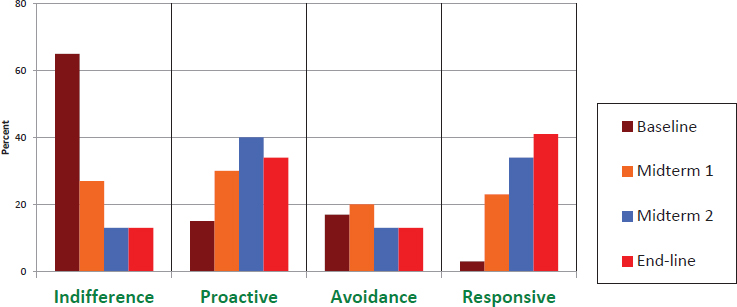

their level of self-efficacy—that is, personal beliefs in their ability to successfully accomplish a task or achieve a goal. In the case of his work with HIV, his team asks people a series of questions based on two dimensions: whether they perceive their risk as low or high and if they have a weak or a strong sense of personal efficacy. He classifies individuals who perceive both their risk and efficacy to be low as indifferent and those who have a high risk perception and low levels of efficacy as avoidant. Individuals who have a low risk perception but higher levels of efficacy are proactive, and those with a strong perception of risk and a strong belief in their ability to do something about that risk are considered responsive.

Based on this framework, his team’s efforts have focused on moving as many people as possible into the responsive category. In Malawi, where he has been working for over a decade, increasing perceived risk among those who have a low sense of personal efficacy may actually lower their intention to use condoms (Rimal et al., 2009a,b). For those who have higher levels of personal efficacy, increasing their perception of risk may have the desired effect of boosting their intention to use condoms. After 9 years, the risk communication campaign reduced the percentage of people in the indifferent group from 60 percent of those who participated in the study to 15 percent (see Figure 3-4). At the same time, the percentage of people in the responsive group rose from about 3 percent to 40 percent. “We were able to push people into the desired category,” said Rimal.

SOURCES: Rimal presentation, December 13, 2016; republished with permission of Sage Publications, Inc., from Public Communication Campaigns, Rice and Atkin (eds.), Rimal and Limaye, 4th Edition, Copyright 2013; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

The bigger question, he said, was whether it mattered that more people ended up in the responsive category. The answer with regard to condom use and being tested for HIV was “yes” (Kaufman et al., 2014). Condom use and testing were significantly higher in both the proactive and the responsive groups, said Rimal. “Pushing people to [the responsive group] helped translate people’s perceptions of risk to actual behaviors,” he said, adding that self-efficacy is the more reliable predictor of behavior. “It is not a matter of just getting people to feel scared. It is a matter of informing people exactly what they need to do to take control of the situation,” said Rimal. “Feeling efficacious, that is a wonderful basket in which to put all your eggs.”

SOURCES OF INFORMATION: LESSONS FROM COMMUNICATION IN LIBERIA

At the time of the recent West African Ebola outbreak, Liberia was unprepared to deal with a massive public health crisis. The country had few medical resources, no isolation units, little in the way of protective garb, and few health workers who had the proper training to use what resources were available. Moreover, after two civil wars in the late 1980s and late 1990s and decades of political turmoil that devastated the nation’s health infrastructure, the citizenry had little trust in its leaders. “All of that needs to be taken into consideration when we think about how communication was relayed,” said Turner. “Trust is fundamental for both risk and crisis communication, and we were starting out at a baseline where trust was really low.”

The project Turner, Rimal, and their colleagues ran in Liberia aimed to assess quantitatively the presence of crisis communication best practices in both traditional and grassroots communication (Turner et al., 2016). They conducted a content analysis on a random sample of newspapers, radio stations, text messages from health care workers, and a three-panel news chalkboard in Monrovia, the Liberian capital. Turner noted that investigators from Johns Hopkins University designed and implemented some of the radio programs to serve as an intervention. Communication was coded according to a wide range of parameters and analyzed to identify the sources of risk communication, who was being cited or explicitly interviewed for stories, and whether the stories mentioned if those individuals were experts in the topic and trustworthy or untrustworthy (see Table 3-1).

One interesting finding, said Turner, was that trustworthiness was almost never communicated, but lack of trustworthiness was. She explained this situation was not the result of an unwillingness to talk about trust, but rather that the media thought it pertinent to mention if someone was

less than trustworthy. The analysis also found that whom or what people blamed for the Ebola crisis depended on the modality (see Table 3-2). In newspaper stories, the main culprits were the Liberian government and the disease itself. Turner noted a number of rumors were circulating that the Liberian government had brought Ebola to the country on purpose. Stories that were run on popular radio stations largely blamed the United States and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), but the radio programs blamed God and witchcraft as sources of the outbreak to convey that the outbreak was a natural phenomenon.

As far as who received credit for helping resolve the crisis (see Table 3-3), newspapers credited the Liberian government and NGOs most often, while radio stories, both on popular radio and in the designed programs, gave God all of the credit for resolving the crisis. In fact, said Turner, radio portrayed the problem as one God caused and only God could fix, creating a problem for risk communication that tries to engage human action to reduce harm.

To track rumors, the project team asked community health workers to text any rumors they heard to a central number at the project coordinating center (see Table 3-4). The project team then issued a newsletter and informed the media about the rumors that were prevalent and provided media outlets with information to debunk these rumors. Community members were the primary source of rumors, and the most common rumors were about new Ebola cases. “We had no proof whatsoever that new cases were emerging, but there were many rumors about new cases,” said Turner.

Some rumors concerned people who were profiting from the Ebola crisis and did not want the crisis to end, and a significant number of rumors promoted the idea that Ebola was not a naturally existing disease but was created by an outside source, such as the United States or the Liberian government. Rumors assigning blame focused mainly on the Liberian government or the president, with the United States and health care workers also coming under fire.

When Turner and her colleagues looked at whether these rumors were debunked, they found that, although the number of rumors increased during the crisis, overall refutations did not increase as quickly. Newspapers, however, were particularly vigilant about refuting rumors, and throughout the crisis, newspaper stories debunked rumors as quickly as they appeared. This result, said Turner, shows the value of forming strategic alliances with the media to control rumors as they happen and counter false information. The question that remains unanswered, because the study did not include collecting the necessary data on human perception, was whether debunking rumors quickly had any effect on human perception. Turner urged that this question should be explored in future studies.

| Sources Cited | Liberian Government | African Union | Ellen Johnson Sirleaf | ECOWAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newspaper | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 447 | 15 | 171 | 26 |

| Expertise mentioned | 232 | 6 | 74 | 12 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 12 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 39 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Radio | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 2 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Expertise mentioned | 2 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Radio program | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Expertise mentioned | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SMS | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Expertise mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chalkboard | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Expertise mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Education Officer | WHO | U.S. Centers for Disease Control | Doctor(s) | Health Care Workers (non doctor) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 179 | 56 | 129 | 160 |

| 5 | 62 | 21 | 110 | 45 |

| 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 13 |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 5 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 2 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sources Cited | Ebola Patient | Family of Patient | Community Member | U.S. Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newspaper | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 125 | 53 | 262 | 99 |

| Expertise mentioned | 22 | 2 | 103 | 46 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 1 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Radio | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 6 | 4 | 26 | 0 |

| Expertise mentioned | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Radio program | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 3 | 1 | 21 | 0 |

| Expertise mentioned | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SMS | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 |

| Expertise mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chalkboard | ||||

| Mentioned/Cited | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| Expertise mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of trustworthiness mentioned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NOTE: ECOWAS = Economic Community of West African States; SMS = Short Message Service; U.S. AFRICOM = United States Africa Command; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCE: Turner presentation, December 13, 2016.

| U.S. AFRICOM/U.S. Military Forces | Celebrity (general) | Celebrity (soccer) | Liberian Ministry of Health | Liberian Ministry of Information, Cultural Affairs, Tourism | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 | 9 | 10 | 201 | 44 | 450 |

| 15 | 3 | 4 | 88 | 14 | 219 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 22 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 47 | 4 | 16 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 44 | 3 | 9 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 3 | 28 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 3 | 21 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

TABLE 3-2 Assignment of Blame for the Ebola Crisis According to Different Media Sources

| Source | Newspaper | Radio | Radio Program | SMS | Chalkboard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberian Government | 11.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 36.7% | 5.9% |

| Ellen Johnson Sirleaf | 0.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.0% |

| United States | 1.2% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 17.6% |

| Health Care Workers | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 13.3% | 0.0% |

| Victims Themselves | 5.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.3% | 0.0% |

| Ebola Itself | 20.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 47.1% |

| WHO | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| NGO | 0.7% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 3.3% | 0.0% |

| Religion | 1.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Witchcraft/Voodoo/Karma | 0.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 3.3% | 0.0% |

| Family of Sick | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| God | 0.2% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 3.3% | 5.9% |

| No One | 50.1% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 23.5% |

| Other | 6.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% |

NOTE: NGO = nongovernmental organization; SMS = Short Message Service; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCE: Turner presentation, December 13, 2016.

| Source | Newspaper | Radio | Radio Program | Chalkboard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuban Government | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.9% |

| Other Foreign Government | 7.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.9% |

| Liberian Government | 21.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 17.6% |

| Ellen Johnson Sirleaf | 5.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 11.8% |

| United States | 8.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.9% |

| Health Care Workers | 11.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Victims Themselves | 3.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Ebola Itself | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| WHO | 7.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| NGO | 19.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Religion | 3.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Witchcraft/Voodoo/Karma | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Family of Sick | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| God | 0.4% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| No One | 11.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 52.9% |

| Other | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

NOTE: NGO = nongovernmental organization; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCE: Turner presentation, December 13, 2016.

TABLE 3-4 Rumors About Ebola Circulating in Liberia

| Mentioned Rumor | Count | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ebola was created by an African source | 3 | 2.1 |

| Ebola was created by an outside source | 14 | 9.9 |

| Ebola is not real | 1 | 0.8 |

| Routine vaccines are being used to infect people with Ebola | 1 | 0.8 |

| Ebola vaccine trial and routine vaccines are the same thing | 1 | 0.8 |

| Ebola vaccine trial is being used to infect people | 8 | 5.6 |

| ETUs are just a place for people to die | 2 | 1.4 |

| Liberian government has misused donated funds | 2 | 1.4 |

| People are profiting from the Ebola virus | 22 | 15.5 |

| School-related rumors | 13 | 9.1 |

| Rumors about new Ebola cases | 40 | 28.1 |

| Issues with prevention measures | 8 | 5.6 |

| Misinformation contagion | 19 | 13.3 |

| Other | 8 | 5.6 |

| Total | 142 | 100 |

NOTE: ETU = Ebola treatment unit.

SOURCE: Turner presentation, December 13, 2016.

ADVOCACY AND COMMUNICATION OF HEALTH RISKS: EXAMPLES FROM TOBACCO CONTROL

Over the course of his presentation, Niederdeppe aimed to answer two questions: What factors determine the success or failure of public communication campaigns targeting individual behaviors, and what impact can health risk messages have on support for policies to remedy those threats?

To address the first question, he argued that health risk campaigns work when they focus on behaviors and their context, not necessarily the risks per se. As an example, he said the reason society cares about smoking is that it kills people, but harping on the health risks of smoking may not be the most effective way to prevent people from smoking or get them to quit smoking. As evidence for this, he cited the results of a study he and his colleagues conducted (Niederdeppe et al., 2004) using data from the Florida TRUTH Campaign, one of the first well-funded youth smoking prevention campaigns that ran in the late 1990s. When they looked at the relationship between beliefs and smoking behavior among Florida teens, beliefs about the health hazards of smoking had no predictive value when it came to whether a person smoked in the prior 30 days. What mattered to

the teens, Niederdeppe said, were beliefs about cigarette companies lying to them or that cigarette companies were trying to get them to start smoking.

Based on these findings, the national TRUTH campaign that evolved out of the Florida project developed a logic model based on the premise that beliefs about the tobacco industry and cigarette companies would make young people less receptive to the industry’s marketing practices. These beliefs, in turn, would make many young people want to assert their independence from a powerful industry trying to manipulate them. An evaluation of the campaign found that this approach did reduce the odds that young people would start smoking (Farrelly et al., 2005). “The point is, you do not necessarily have to start with the premise that health risk beliefs are going to be the most effective communication strategy,” said Niederdeppe.

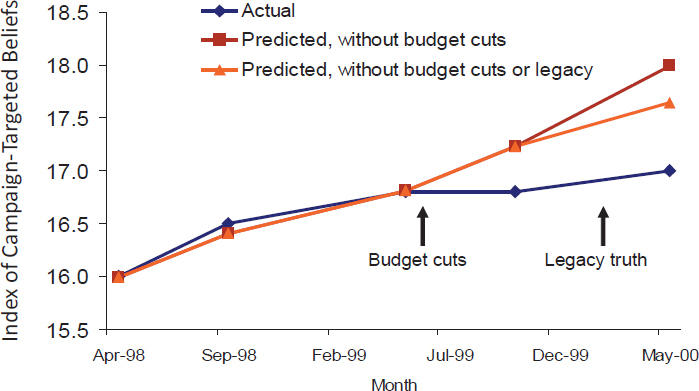

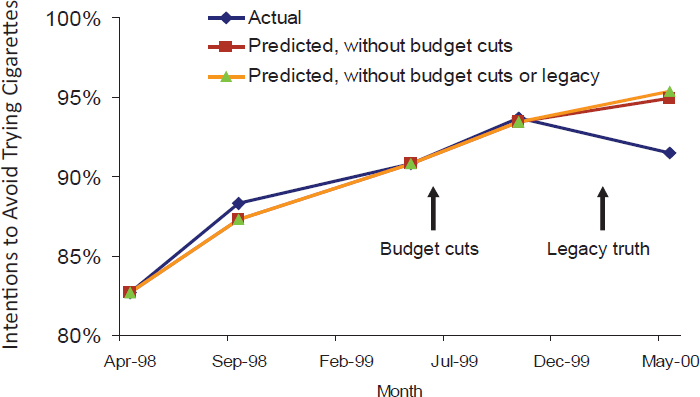

Another factor that determines whether health campaigns work is achieving frequent, sustained, and widespread exposure from many sources. A systematic review of the available evidence (Durkin et al., 2012) suggests that, to be effective at promoting smoking cessation, campaigns may need to average about 4 exposures per month, with the effects increasing up to about 10 exposures per month. Unfortunately, said Niederdeppe, campaigns do not work like vaccines. “When the campaign goes away, so do the effects,” he said. In Florida, for example, the state legislature cut funding for the program after its first year because it was so successful, and almost immediately campaign-targeted beliefs (see Figure 3-5)

SOURCES: Niederdeppe presentation, December 13, 2016; data from Niederdeppe et al., 2008a.

SOURCES: Niederdeppe presentation, December 13, 2016; data from Niederdeppe et al., 2008a.

and the intention to avoid trying cigarettes (see Figure 3-6) stopped rising (Niederdeppe et al., 2008a).

Niederdeppe noted that research has also shown that anti-smoking communication campaigns work better when the environment supports the behavior the message advocates. With smoking, for example, a campaign will work better when there are higher taxes on cigarettes, indoor smoking bans, and restrictions on cigarette marketing (Wakefield et al., 2010). Another major factor for success is having resources such as sufficiently staffed quit lines available to help people stop smoking.

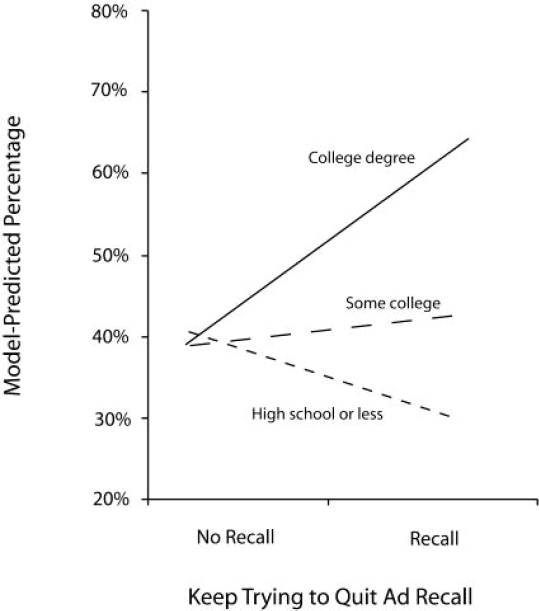

Successful campaigns also take the socioeconomic context of the behavior into consideration in message design, Niederdeppe added. Smoking, like almost every other health issue, disproportionately affects the poor, so testing messages on focus groups populated by college-educated young adults is not likely to produce the most effective messages for the largest population of smokers. Wisconsin, for example, ran a quit smoking campaign that emphasized how to quit, and when Niederdeppe and his colleagues looked at the relationship between recall of the ads and intention to quit smoking within the next 30 days, there was a significant strong association among individuals with a college degree (see Figure 3-7). However, among those with less education—the predominant population of U.S. smokers—there

SOURCES: Niederdeppe presentation, December 13, 2016; reprinted with permission from Niederdeppe et al., “Smoking-cessation media campaigns and their effectiveness among socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged populations,” American Journal of Public Health, 98(5), 916-924, Copyright 2008, American Public Health Association/Sheridan Press.

was either no association or a negative association (Niederdeppe et al., 2008b).

Niederdeppe noted that the tobacco control community debates whether to emphasize how to quit or why to quit in its messages. As Brewer pointed out earlier, graphic warnings, which emphasize why to quit, can deliver effective messages (Brewer et al., 2016; Noar et al., 2016), and Niederdeppe and his colleagues have also found this effect, though the association decreases with increasing years of education (Niederdeppe et al., 2011). The same study also looked at the perceived effectiveness of “how to quit” ads, and although they were less effective overall than “why quit” ads, they showed increasing effectiveness as education level increased.

With regard to the impact that health risk messages can have on support for policies to remedy those threats, Niederdeppe said increased news attention to health risks does increase the likelihood of legislative actions related to tobacco. His own work, for example, has shown that exposure to state tobacco cessation campaigns emphasizing secondhand smoke is associated with increased support for clean indoor air laws, which again create a conducive environment for tobacco cessation (Niederdeppe et al., 2007).

As a final thought, Niederdeppe talked about health risk communication as it relates to infectious disease threats and policy change. Tobacco cessation, he said, has been a topic of concern for a long time, which is not the case with many infectious diseases. Given that targeting policy makers is not a precise science, messages that may be effective at getting a policy maker to consider taking action could increase fear among the public without also creating efficacy to do anything about that fear.

DISCUSSION

Kent Kester, vice president and head of translational science and bio-markers at Sanofi Pasteur, commented that the world is operating today in an era of rapidly moving communication strategies, a challenging environment for large, bureaucratic organizations with formal procedures for communicating with the public. He wondered how organizations can compete with the deluge of misinformation that can spread through social media and the Internet given the rise of well-meaning citizen journalists and not-so-well-meaning purveyors of fake news. Fagerlin suggested that risk communicators should learn from the advertising knowledge base and from the approaches that heavily trafficked websites use to draw large audiences. “It might feel distasteful in some sense to do this,” she acknowledged, but added that once such techniques draw people to credible news sources, they can then get the nonfake, accurate information they need.

Kreps noted that he recently visited the Chinese Food and Drug Administration, which was having a big problem with false reports about food-borne disease outbreaks. Its solution was to create a tracking network that within 5 minutes of seeing a new message can analyze it, assess its accuracy, and provide a response to help minimize the impact of a false story. “I think we are going to have to do the same kind of thing of not allowing false information to stand, but to be able to respond to it quickly,” said Kreps. Brewer recommended an authoritative review of how to address and debunk rumors (Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Fischhoff added that the expert community should give up its resistance to saying something without being certain at a level that would satisfy a peer-reviewed journal. “That is important in its own right, but it does not serve the public health need,” said Fischhoff.

At a time of crisis or when circumstances warrant a fast response to some piece of information, it is critical to have preidentified the sources of information that different audiences already trust, said Kreps. In many cases, he explained, the most at-risk populations do not trust the experts. They do not want to hear from the head of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the Surgeon General. “They trust local sources, the groups they communicate with,” said Kreps. The paradox, he said, is that some of these trusted sources often have the worst information. “So one of the things that we need to do as public health communicators is build alliances with those trusted sources and provide them with relevant information,” he said. The situation with childhood vaccines is a prominent example of this phenomenon, he added. He and his colleagues have been building relationships with the “mommy bloggers” who today are one of the trusted sources for young mothers. This effort, he said, has started making a huge difference in how young mothers feel about vaccinating their children. Brewer said the effort to promote vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) is also focusing on specific bloggers and popular social media sources to address misconceptions about the vaccine.

Kreps acknowledged that this early stage of the digital revolution is somewhat problematic, when a few “loud, squeaky voices” are making trouble. He believes, though, that over time the public will become more literate about their use of social media. On a positive note, he said the wisdom of the crowd is already having a positive effect on the veracity of information disseminated in online patient support groups. There was an initial fear with online cancer support groups that some members would provide bad information, but what has been happening is that these groups are self-policing and are providing the latest, most accurate information. “I have a feeling that within social media communities, there will be more watch dogs who will spring up and out people who are providing bad information,” said Kreps.

Fagerlin took issue with Kreps’s optimism and suggested that cancer support groups might be the exception rather than the rule because they are small communities filled with knowledgeable people, and there is a ready supply of accurate information available. Her concern involves areas in which people might not know as much and are going more on gut intuition than fact. “I think there is a real threat for a lot of misinformation, especially in moments of hysteria,” said Fagerlin. She called for the risk communication field to start studying social media and paying as much attention to it as it does to how to communicate information.

Preparedness and Flexibility for a Rapid Response

Lonnie King, professor and dean emeritus of The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, asked how much public health agencies and universities should prepare in advance for the next infectious disease crisis given that the response to one situation is likely to have at least some similarities to past situations. Kreps replied that it is important to distinguish between strategy and tactics. Preparing strategies ahead of time by using the accumulated knowledge base about what works with which audiences is a good idea, but tactics require situation-specific information. He cautioned, too, that times change and tried-and-true methods that worked 2 years ago may not work anymore. However, strategies that identify key populations and the channels that reach them, as well as ongoing activities that build relationships in communities, can serve as a starting point for responding quickly to a rapidly developing situation. Fischhoff said that absent a strategy and a protocol in place to reach out to the experts and the community, every problem will get away, but with a strategy and protocol in place, it is possible to create messages, prototype them, and produce a rough response within 6 hours with modest resources. An important point, though, he added, is to follow that rapid response with evaluation and refinement.

Commenting on the importance of communicating early in the face of uncertainty, Jay Siegel, chief biotechnology officer and head of scientific strategy and policy at Johnson & Johnson, asked if research has revealed anything about the risks of being wrong. As an example, he noted how there are always people who refuse to evacuate in the face of a major hurricane because previous forecasts of impending danger were wrong. “If we communicate because we need to communicate early, and then we are wrong, do we run a major risk of undermining confidence the next time?” asked Siegel. The problem, Fischhoff replied, is that “if we do not say anything, somebody else will.” The right question to ask, he said, is “What can we say that is responsible and defensible?” After that first question, he continued, we then ask how quickly people need better information, how quickly that better information can come, and how information can be conveyed in a nuanced way to people who are willing to listen.

Fagerlin agreed with Siegel that the risk communication field needs to better understand the implications of putting out an incorrect message, but she noted that information will never be perfect in the middle of an outbreak. “There is always going to be uncertainty, but we should not be paralyzed by that uncertainty,” said Fagerlin. “We do have to be as careful as possible because there will be downstream effects if we are completely wrong frequently.”

Kreps said he advises joint information centers to provide good information as quickly as possible in times of a crisis and then say, “This is the

best information we have now, but we are going to provide you with regular updates. Be aware that we are going to keep monitoring the situation. As things change, we will provide you with updates and recommendations.” This type of strategy, which establishes a dialogue with the public, is likely to work best in a crisis. “If you let people know that you are using your best judgment based on available information and that you are seeking more information to update that, I think they will be more willing to listen to you and adapt over time,” said Kreps.

Whether that approach works may depend on the specific scenario in which it is used. For example, when Fagerlin and her colleagues used that very language to talk about vaccinations, they observed that people’s risk perception and their interest in vaccination decreased in 11 countries they worked in. In contrast, Fischhoff reflected that during a flooding crisis in Des Moines, Iowa, the head of the Iowa water board stood in front of a microphone every 12 hours and said, “This is what we promised to do. This is what we learned. I will take questions as long as you want.” The response to this approach was so positive, said Fischhoff, that it inspired someone to write a country song about this man.

Continuing with the theme of how to respond rapidly during an emerging health situation, Jeffrey Duchin, health officer and chief of the Communicable Disease Epidemiology and Immunization Section for Public Health in Seattle and King County, Washington, asked for advice on how to respond to the tremendous pressure from the media to answer questions. Kreps replied that it is critical to communicate as close to time zero as possible but to remember that communication not only serves to disseminate information but also to build relationships. “You may not have all the content at that point, but it is a great opportunity for you to demonstrate compassion, concern, and involvement, and to build your trust with that community,” said Kreps. “Seek information from them. Let them know what you know now and what you hope to learn.”

Duchin also asked how generalizable the information is with respect to how different groups respond to various types of messages. Fagerlin said she designed her 11-country study, in part, to answer that question. Although the results showed small differences across the 11 countries, the responses were largely consistent. She noted that she and her colleagues are preparing to look at how different communities react to different communication strategies for addressing outbreaks involving four infectious diseases—Middle East respiratory syndrome, Ebola, Zika, and influenza—to see if the exact same messaging tactics work in those four domains.

Rima Khabbaz, deputy director for infectious diseases and director of the Office of Infectious Diseases at CDC, commented that communication about an endemic health risk, such as smoking, is likely to be different than the communication taking place at a time of crisis, which may warrant

immediate action. She asked if data exist on risk reduction behavior change during a crisis. Turner replied that she and colleagues at the University of Kentucky had recently completed a study testing messages that would trigger an evacuation during a tsunami. This would not, she said, be a case in which the messages would encourage people to seek information. “In a tsunami, you do not want people to get on the Internet and check things out. You want them to hightail it out of there, and that takes a different sort of messaging,” Turner explained. She and her colleagues found that short, terse, clear messages about the severity of the situation and with a very clear behavior—do this, go here, use this route to get there—were most effective. The tsunami messages were all one-way communication, whereas in many risk scenarios the goal would be to engage more in conversation with the target audience.

Brewer agreed that in time of crisis the less said the better. “People can take in less and remember less when they are under an extraordinary state of threat,” he said. Instead of making a dozen points, hone the message down to three at most, and provide specific behaviors, he recommended.

Motivating Change

Jonna Mazet, professor of epidemiology and disease ecology at the University of California, Davis, sought more clarification on Brewer’s earlier point about risk communication as a weak intervention for behavior change. Brewer responded that the effectiveness of risk communication depends on the intended goal and context. Rimal explained further that it is important to keep in mind that behaviors are heterogeneous, so the approaches—whether they are risk communication campaigns, policies, or other interventions—implemented for behavior change vary, depending on the type of behavior, the context in which the behavior is being enacted, and the underlying characteristics that define that behavior. For example, getting people to get a flu shot requires a different approach than getting people to change engrained, addictive behaviors that they have been engaging in for many years, like smoking. “I would want us to walk away from this notion that there is one formula for changing behaviors,” said Rimal.

Duchin commented on the possibility that risk communication may not produce behavior change because it does not provide any messages on how to change. Rimal responded by pointing out how people process risk information. He cited one of his favorite commercials as an example. It shows a suburban family where everything is going well when suddenly a burglar appears and everyone is scared. The commercial, however, then produces a solution—a burglar alarm. This advertisement illustrates an effective technique of scaring people and then providing an easy solution to their fear.

The key, though, is not solely to motivate people but to facilitate the desired action. “You have to help people translate motivation to actual change, and efficacy does that,” said Rimal. In fact, he said, four decades of research have provided specific approaches to improving people’s sense of efficacy. Brewer noted there has to be a concrete behavior that people engage in to mitigate risk, but particularly during time of crisis, there may not be specific guidance to provide to the public.

Rimal mentioned that in some cases risk communication misses the mark with regard to the context that most concerns the public. The situation with indoor tanning is a case in point, he said. Although public health messages all focus on the cancer-causing potential of indoor tanning, tanning bed companies all stress physical attractiveness. Similarly, efforts to promote condom use focus on disease and pregnancy prevention, but the companies selling condoms focus on debunking the myth that condoms reduce sexual pleasure. Rimal’s point was that it is important to remember to look at behavior change from the perspective of the target audience, which is often different from a disease prevention perspective. Niederdeppe added that one inexpensive way of gaining that perspective is to pay attention to the kinds of conversations that are happening around a particular issue, such as tanning beds.