4

Achieving Effective Communication

The morning sessions of the first day of the workshop focused on the science, research, and scholarship around strategies for building effective communication capacity, providing the groundwork for the stories from the field that were the subject of the afternoon’s presentations. The five speakers who discussed effective communication in practice were Dina Maron, medicine and health editor at Scientific American; Heidi Larson, director of the Vaccine Confidence Project and associate professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; Kacey Ernst, associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Arizona; Nick van Praag, director of Ground Truth Solutions (GTS); and Damien Chalaud, executive director of the World Federation of Science Journalists (WFSJ).

PACKAGING A STORY: TRADITIONAL VERSUS DIGITAL MEDIA

A decade ago, a story was considered successful if it appeared above the fold in The New York Times or if it ran in Time magazine. “Now, we might know that in terms of eyeballs on a story and getting your message out—more people are getting their news digitally,” said Maron. Today, more people will see a story on nytimes.com or scientificamerican.com than in the print version of those publications, and so, during an infectious disease outbreak, getting the word out on a digital platform is more likely to have a timely effect, she said.

When trying to decide on the form of a message—a story, a question- and-answer piece, a graphic, a podcast, or a video are a few options—there

are several factors to consider, said Maron. In some cases, the important thing is to get facts out quickly. At other times, the point of a communication is to have an expert help the public understand something new, such as Zika. There will be times, too, when the public would benefit from having a variety of voices and perspectives conveying information. Each of these cases, said Maron, would likely be best served by a different form for the message.

Communication about Zika, for example, was better served by digital media than print media, noted Maron. In January 2016, Zika was still relatively new in the United States, and all cases were travel-related at that point. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was not yet tracking the virus or publicly announcing where Zika cases were appearing in the country. Maron believed it was valuable for the readers of Scientific American, as well as the public, to know that Zika was not entirely new to the United States, that the first case in the country occurred in 2007 in an Alaskan who had volunteered in response to an outbreak in Southeast Asia. Maron called the health departments of all 50 states and the District of Columbia and got information about where Zika cases had been so far, and she updated it daily for a few months until CDC started publishing the information. Published online as an interactive map, this information was used by several public health departments as a resource to better understand what was happening contextually, said Maron. Eventually, the map appeared in the physical magazine, but it was most useful to the magazine’s audience because it provided new information daily.

Maron said she gets story ideas about infectious diseases from researchers, physicians, health departments and agencies, advocacy groups, and crowdsourcing. “It could be we hear a blip about something on Twitter or Facebook, and our goal would be to get the facts out, dispel rumors, raise awareness, and humanize the problem,” she explained, adding that these goals are not much different from the general public health goal. Social media, she said, are changing the landscape by making the world more dynamic. “There is no more one-dimensional communication, where a bulletin is sent out,” she said. When the Boston Marathon bombing happened, 80 percent of Americans followed the story on television, but 49 percent kept up with the news online or on a mobile device, with 26 percent following the story on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media networking sites (Pew Research Center, 2013).

Maron believes that social media’s popularity as a timely information source can be a good thing from a public health perspective, even though it can cause problems if the information getting out via social media channels is not accurate. A viral tweet or a Facebook message, for example, can alert the media to a story, but it can also fuel panic if the information is wrong and public health officials are not able to react quickly to halt

the spread of misinformation. For example, on August 7, 2014, during the Ebola outbreak, a Nigerian undergraduate student tweeted as a joke, “The Ministry of Health is urging the public to prevent an Ebola attack by drinking saltwater or bathing in saltwater.” The tweet went viral and within 1 day, 2 people had died and 20 more were hospitalized because of excessive consumption of salt water. Nigerian officials stepped in quickly and through intensive social media work debunked that tweet and stopped the flow of misinformation.

In terms of practical advice for public health experts and responders, Maron recommended being vigilant online to see what information and misinformation are spreading, perhaps even making that task part of someone’s job. She suggested contacting the media or holding press conferences to get accurate information out as fast as possible, before rumors take hold; to share information on multiple platforms; and to value digital as well as print media. “One of the most important recommendations I can make, and it is maybe slightly at odds with some of the data that Dr. Fagerlin mentioned this morning, is that it is valuable to also say what you do not know,” said Maron. She pointed out that some of the best public health communicators, such as Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, or Thomas Frieden, former director at CDC, are known for providing the most current information, noting that it is changing daily, and that the landscape is evolving. “You do not think anything less of them or think they lied to you,” said Maron. “I think it helps everybody to understand the fast-moving target ahead of us.”

RESPONDING TO MISINFORMATION AND RUMORS

Larson began her presentation by quoting Margaret Chan, director of the World Health Organization (WHO), who said, “The days when health officials could issue advice based on the very best medical and scientific data and expect populations to comply may be fading.” Larson noted that changing “may be” in that quotation to “are” would reflect the reality of what she called the “post-fact society.”

Larson’s program, the Vaccine Confidence Project, acts as a surveillance system for public opinion on vaccines. The vaccine issue she worries about the most relates to how the world behaved with regard to the H1N1 outbreak and what she called the horrible worldwide noncompliance around the vaccine. She noted this noncompliance was not just a U.S. or European phenomenon—she received a call, for example, from the Indian Ministry of Health wanting to know why 85 percent of the nurses and trained health professionals in one of India’s states refused the vaccine. What particularly concerned her, she said, was that this response was not just a problem with

a misinformed public. “We need to think of the multilayered perception issues,” said Larson. “It is not just the end users. We have people in the middle, the gatekeepers, the health professionals, and the gatekeepers outside of the health community that we need to put under our lens.”

Vaccine skepticism is not new and, as she mentioned, not just a U.S. or European problem or about the H1N1 vaccine. There are continuing and growing anxieties about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and the mumps-measles-rubella (MMR) vaccine, and those concerns are spreading. Malaysia, for example, has a large anti-MMR group emerging, and just a couple of years ago she saw a headline in a major Kenyan newspaper that read, “Are vaccines making your child mentally ill?” Although it would be easy to blame the Internet, social media, and smartphones for the problem, Larson said the issues are deep and historic.

As the day’s discussions illustrated, rumors have a bad reputation, said Larson, but rumors, like reports of drug-related adverse events, can be valuable signals of an impending problem. Many rumors turn out to be untrue, but it is important, she said, not to dismiss them immediately as “not fact.” Rumors thrive on uncertainty, so often the worst response to a rumor is to say, “No comment.” In addition, rumors can signal the beginning of a disease outbreak. For example, the Global Health Security Agenda1 has a profiling project in Vietnam that looks for rumors, such as a teacher seeing an unusually high number of children absent from school and hearing they all have similar symptoms. This could be a coincidence, or it could be the first sign of an epidemic, and thus is a rumor that deserves follow-up. She also noted that the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network,2 a WHO partner, listens for rumors, assesses their epidemiologic significance on a daily basis, and determines the need for a response.

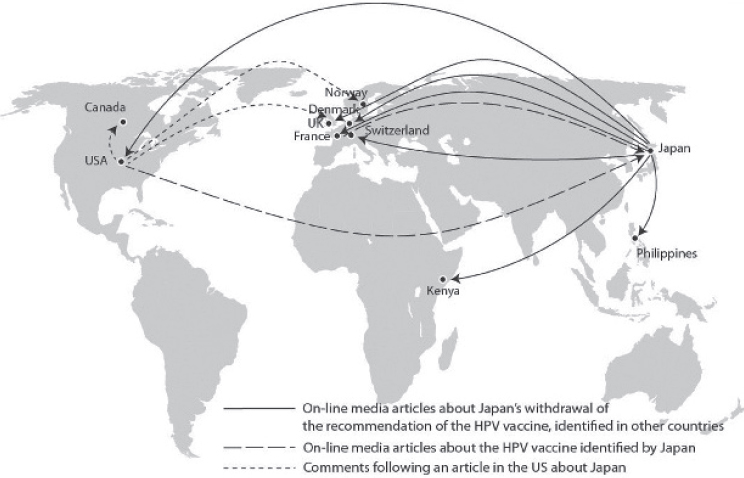

At the Vaccine Confidence Project, Larson and her colleagues believe that rumors, whether right or wrong, are an indicator of the underlying belief systems, personal histories, and sociopolitical environment of those who believe them. “Whether they are fact or fiction, they can and do have serious impacts on people’s individual and collective behavior,” said Larson. These days, rumors travel globally, and she and her collaborators are trying to develop a global picture of how rumors spread and evolve in today’s highly connected world. One study she conducted (Larson et al., 2014) looked at the global spread of vaccine sentiments following Japan’s suspension of its HPV vaccine recommendation in June 2013 (see Figure 4-1). The

___________________

1 The Global Health Security Agenda is a growing partnership of more than 50 nations, international organizations, and nongovernmental stakeholders that helps build countries’ capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease threats. See www.ghsagenda.org (accessed March 16, 2017).

2 The Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network is available at www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/partners/en (accessed March 16, 2017).

SOURCES: Larson presentation, December 13, 2016; Larson et al., 2014.

Japanese Ministry of Health told her bluntly that they knew no scientific evidence suggested any causal links between the vaccine and adverse events, but the political pressure from anti-vaccine groups forced their hand.

Citing the old saying, “When the United States sneezes, the world catches a cold,” Larson said when some rumors circulate in the United States, the rest of the world starts questioning vaccines, a phenomenon whose impact is underestimated. The rumor street runs two ways, however, and she frequently checks U.S.-based anti-vaccine websites to see what is happening in the rest of the world because the groups that run these sites are themselves searching for any evidence to rationalize their concerns. “Whether it is a village in Bangladesh, India, or Ouagadougou where a child is reported reacting to a vaccine, it will be on their site and they are saying, ‘You see! They are not telling us the truth,’” said Larson.

Rumors have public health impacts, as illustrated by an incident in northern Nigeria during 2003 and 2004. At the time, rumors triggered a boycott of the polio eradication efforts there that led to an outbreak that spread to more than a dozen countries in Africa, as well as Saudi Arabia and Indonesia. A similar episode with polio vaccination happened in Pakistan in 2013 in response to a rumor that the hepatitis B vaccination initiative there was part of a Central Intelligence Agency plot. In Kenya,

Catholic bishops called for a halt in tetanus vaccinations that led to a boycott of polio vaccination.

Incidents such as these led Larson to establish the Vaccine Confidence Project as a means of anticipating problems associated with rumors and other sources of misinformation and countering those problems while they are still manageable. The project’s premise, she explained, is that early detection of and timely response to vaccine rumors can prevent loss of public confidence in immunization, program disruptions, and potential disease outbreaks. To realize this premise, she developed what she called a diagnostic tool (see Table 4-1) that finds triggers, assesses the amplifiers that determine which triggers are more likely to spread, and then assesses potential impacts.

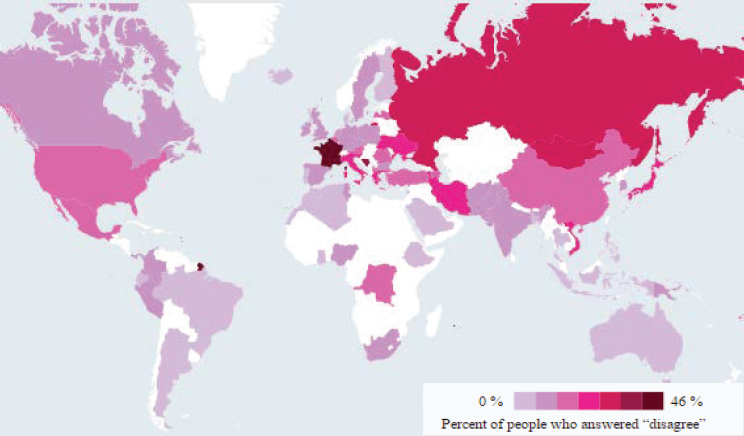

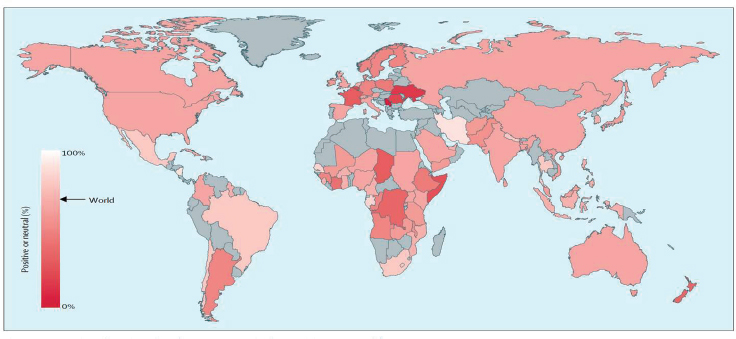

Larson and her colleagues have spent time developing metrics to put a finger on the pulse of public confidence. “We see that public confidence in vaccines is very much a window on public trust in government in particular, but also in systems,” she said. One study, a 67-country survey in 2016 of vaccine confidence (Larson et al., 2016) elicited responses to the statement, “Overall, I think vaccines are safe,” found that vaccine sentiment is particularly negative in Europe and Eastern Europe, with France being the most skeptical by a wide margin (see Figure 4-2). She noted that the French government is aware of this problem and is concerned about it. An earlier study using a media surveillance system to analyze public concerns about vaccines (Larson et al., 2013) found nearly identical results (see Figure 4-3).

Sometimes, she said, the solution to the rumor problem lies outside the vaccination program itself and needs to consider the contextual, historical,

TABLE 4-1 The Vaccine Confidence Project’s Rumor Diagnostic Tool

| I. Rumor Prompters (“the triggers”) | II. Sustaining and Amplifying Factors | III. Outcome and Impact |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

SOURCE: Larson presentation, December 13, 2016.

SOURCES: Larson presentation, December 13, 2016; reproduced with permission. Copyright © (2016) Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

SOURCES: Larson presentation, December 13, 2016; reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 13, Larson et al., 2013, “Measuring vaccine confidence: Analysis of data obtained by a media surveillance system used to analyse public concerns about vaccines,” Pages 606-613, Copyright (2013), with permission from Elsevier.

and current societal and political factors that might influence public confidence in a vaccine and vaccination program. When countering a negative rumor or conspiracy theory, Larson recommended considering the “fertile ground” factors that make the rumor popular in the first place. In some instances, changing delivery strategy or the actors involved can dispel rumors. Religious figures, she said, can be strong allies for immunization given that they are invested in the well-being of their followers. When excluded, however, religious leaders may become barriers to public confidence in vaccines, as was the case in Kenya. It is also important, she said, to build confidence within the health sector itself. Providers, said Larson, need to feel confident in the safety of the vaccines they are recommending and confident in the answers they give to parents.

Currently, she and her colleagues are leading a community engagement effort in Sierra Leone to manage rumors about one of the new Ebola vaccines being tested in a clinical trial there. “We have social science teams being the ears and eyes for rumors, constantly cycling back to the outreach team, and then liaising with the clinical teams,” said Larson. “It has been really effective.” Power, fairness, trust, dignity, and respect, developed through relationships, have shown to be important in the success of this effort (Enria et al., 2016). In Ghana, political rumors led to a halt in the same trial.

As a final thought, Larson said, “Current and historic examples speak to the importance of time context—past, present, and future—and never, never, never assume what is in the minds of people, and never forget that they can change.”

PARTICIPATORY SURVEILLANCE AND SOCIAL LISTENING

The first recorded cases of Zika occurred in Uganda and Tanzania in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and over the years sporadic cases appeared across the globe. Then, over a short period in 2015 and 2016, there was growth in the number of geographic areas affected by the virus that Ernst said was staggering. One reason for Zika’s rapid spread across the globe, and a major challenge to controlling this pandemic, is that its vector, the mosquito Aedes aegypti, is highly invasive and cannot be controlled by a purely top-down, militaristic-type campaign to eliminate its breeding sites.

Given the difficulty of eradicating the vector, Ernst and her colleagues have been working on a project with CDC and the Skoll Global Threats Fund to develop Kidenga, a community-based surveillance and communication app for mobile phones that would engage community members and households to actively seek out and reduce the habitat of Aedes aegypti. This app allows people to report the syndromes they are experiencing, an important issue with Zika because the majority of cases are asymptomatic

or have mild symptoms. Another complicating factor with Zika is that it is poorly understood because it is the first known primarily vector-borne disease that is also transmitted sexually. “The dynamics surrounding how you can communicate both of those risks simultaneously have been a great challenge,” said Ernst.

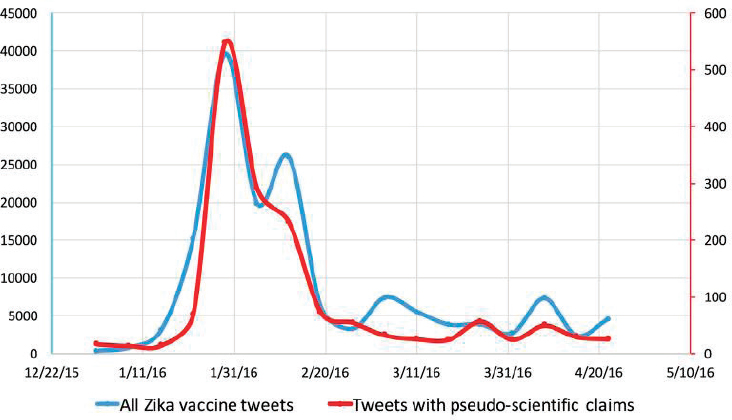

When Ernst reviewed the literature on social listening during the Zika pandemic and how rumors about Zika spread, she found that the number of tweets about a Zika vaccine mirrored the number of tweets with pseudo-scientific claims about the disease (Dredze et al., 2016) (see Figure 4-4). “So most of the evidence, most of the information, that was being posted, did not have great scientific evidence surrounding it,” said Ernst. Another study of Facebook posts about Zika (Sharma et al., 2017) found that, although 81 percent of the posts contained useful information, the 12 percent of posts containing misleading information were shared at a much higher rate.

When she started working on the Kidenga app, Ernst believed it was important that this tool not only get information from communities but provide something in return. In the case of Aedes aegypti, that exchange meant providing communities with up-to-date advice from experts and actions they could take to reduce the risk of contracting Zika and the other illnesses this mosquito can transmit. “The premise is if you have people who

SOURCES: Ernst presentation, December 13, 2016; reprinted from Vaccine, Vol. 34, Dredze et al., 2016, “Zika vaccine misconceptions: A social media analysis,” Pages 3441-3442, Copyright (2016), with permission from Elsevier.

are better educated, who have more self-efficacy, who are more empowered, they are going to be more likely to take some sort of public health action,” Ernst explained. “At the same time, when you have this coupled with the community-based surveillance piece, maybe you can identify early signals that say there is transmission that is occurring.” Her hope is that such early signals will trigger action from the public health department that will allow control of the outbreak.

Because Aedes aegypti spreads multiple diseases, Ernst and her colleagues had to consider the different communication approaches they might need to incorporate in Kidenga. For example, with Zika, a relatively novel pathogen, there will be a need to address rumors, she noted. At the same time, media attention will be high, which may increase public awareness of the dangers of the disease and so risk behaviors may be more readily modifiable because people will be more open to listening to information about it. With dengue, an established pathogen transmitted by Aedes aegypti, there can be complacency and message fatigue to address but also lessons learned from previous outbreaks to exploit.

With Kidenga, Ernst and her collaborators wanted to develop synergies among different communication modalities. An active social listening platform can monitor for rumors and identify health concern priorities. A bidirectional communication platform can address those rumors and health concerns and provide tailored risk awareness from geographically located participatory surveillance. Participatory surveillance can enhance engagement and facilitate access to exposure and syndromic field data with social media feeds. “And while those people who are going to actually participate in the participatory surveillance are likely quite different from the general population, they can be advocates,” said Ernst. “You could see them as a cohort to start spreading better information.”

Ernst highlighted the need to educate and entertain at the same time. In her opinion, sustaining engagement in the general population requires identifying ways to make it fun, exciting, and new to learn about these diseases. “I have an idea of embedding a mosquito hunt game into the Kidenga platform to keep people engaged, give them points for reporting in, and give them new weapons for fighting the mosquitoes, like indoor residual sprays,” said Ernst. Another opportunity she sees is to use Kidenga to provide precision messaging that is personally relevant.

She noted that evaluating the effectiveness of bidirectional communication and participatory surveillance at motivating action will be a challenge. She and her colleagues are also wrestling with the ethical complexities of participatory surveillance. Her institutional review board said this type of project is exempt from its review; the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act may have some purview, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has no regulatory role with this type of project. “So how

do you balance public health action and privacy, and when do you provide public health with user information?” asked Ernst.

Her last comment was on the nature of collaborating with public health in building this type of communication platform. Working out details on logistics and data exchange can be challenging, and the lack of a central location housing public health data is a difficult challenge to overcome, Ernst said. “You have to go to each state and each jurisdiction whose information you want to put on this and solicit their approval,” she explained. She is hopeful that a platform such as this can increase transparency and trust within communities and provide opportunities for rapid dissemination directly into affected communities of critical and accurate information on prevention and control.

BIDIRECTIONAL COMMUNICATION PLATFORMS

In the 1980s, when van Praag began his career with the United Nations High Commission on Refugees, one of his first assignments was working in refugee camps in Eastern Sudan during the Ethiopian famine. The prevailing mindset then was that nobody among the relief workers talked to the refugees about the situation in Ethiopia. “They had an enormous amount to tell us and an enormous amount to offer, but that information was not being tapped,” he explained.

Today, he and his colleagues at GTS are trying to tap into that field intelligence, or what he called inward communication, to find out what people are thinking. To develop their methodology, they turned to the private sector, which he explained is good at listening to consumers, and the associated customer satisfaction industry. Their interactions with the private sector taught them the importance of asking a few questions, examining people’s perceptions, asking these questions frequently to track any changes in perceptions, and then communicating any insights back to the people so they do not feel used.

In 2014, the Department for International Development, a United Kingdom government agency responsible for administering overseas aid, asked van Praag and his colleagues to go to Sierra Leone to solicit feedback from the people who were at risk from Ebola during the outbreak then. “This was an extremely difficult environment to operate in because you could not get out to ask people questions,” said van Praag, who explained that their methodology is based on getting into conversations with people in the community. What they did instead was conduct a citizen survey of a reliable sample of the 6 million citizens of Sierra Leone in December, nearly 9 months after Doctors Without Borders had first sounded the alarm that an Ebola outbreak was starting. Working with GeoPoll, a U.S. company that had a cooperative arrangement in place with the main cell phone pro-

vider in Sierra Leone, the GTS team used cell phones to ask five yes/no/do-not-know questions via text, with respondents receiving 50 cents from GeoPoll for completing the survey. The ability of GeoPoll to geo-locate the phones provided location-specific information to accompany the responses.

The GTS team also conducted a frontline worker survey, working with the several relief organizations that provided the team with the mobile phone numbers of their frontline workers. In total 450 people participated in the citizen survey and 300 in the frontline worker survey. GTS polled each group every 2 weeks in alternating weeks. The team, explained van Praag, spent 3 days collecting data after each poll and the weekend analyzing the data so they could provide them to the National Ebola Response Center for the regular Monday morning briefing. The analysis looked at positive and negative behaviors and what was driving them, the quality of services that relief workers were providing, and some information on outcomes.

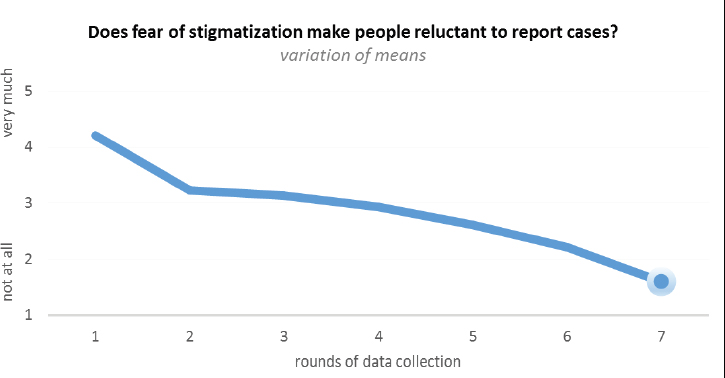

One step van Praag took to increase the value of the information he and his colleagues gathered was to ask people on the ground, both in Sierra Leone and in Liberia, for input on what questions they should be asking and what issues concerned them. The two biggest issues were whether fear of stigmatization made people reluctant to report cases and whether people were following quarantine restrictions. Frontline workers indicated in their first survey that they were seeing a great deal of stigmatization (see Figure 4-5). Though there had been an ongoing unsophisticated communication effort at that time, these initial data were among the triggers that

SOURCE: van Praag presentation, December 13, 2016.

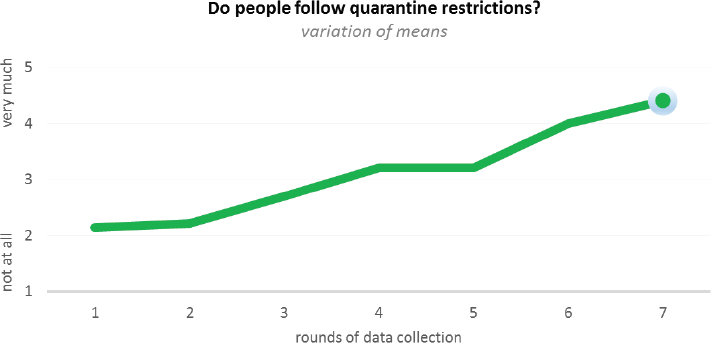

SOURCE: van Praag presentation, December 13, 2016.

launched a nationwide anti-stigma campaign that worked well at reducing people’s fears of stigmatization.

Similarly, said van Praag, the initial results of the survey on quarantine showed very few people were following quarantine restrictions (see Figure 4-6). Again, these results were a trigger for a more concerted communication effort that produced a substantial improvement over the next 7 weeks. The main reason people were not respecting quarantine restrictions, according to the frontline workers, was that security was not enforced.

The citizen survey, however, produced slightly different results. Instead of asking citizens if they were following quarantine restrictions, the GTS team asked if the lack of food and water worried them about the quarantine. Initially, some 80 percent of the citizens replied “yes,” and that level of concern remained constant as the outbreak continued. “Clearly, there was an issue here,” said van Praag, who said the different results from the two data streams led the team to question which one to respond to going forward. Under normal circumstances, he and his colleagues would have gone into the field to get information directly, but that was not possible during the Ebola outbreak. Instead, they launched another survey, which was easy because the quarantine teams had given everyone in quarantine a cell phone. The GTS team recruited and trained teachers, who were free to help because the schools were closed because of the outbreak, and they called frontline workers and people in quarantine.

The first question for those in the quarantine centers was whether they had received their first food package within 48 hours of starting quarantine; 100 percent of the people said they had. When asked if they had received a repeat package during their 21 days of quarantine, almost nobody had in the 100 places the team called. Efforts to alleviate this major problem improved the situation over the next 4 weeks—71 percent of families reported their food needs were met—but people’s needs for water to cook or wash with were not being met, and neither were their needs for medications for regular ailments, such as colds and headaches. The latter was of particular concern because people were worried that the symptoms associated with those ailments would count as Ebola symptoms and they would be removed from their homes to receive treatment.

The results in Liberia were somewhat different, said van Praag, with citizens reporting that the main reason they stayed in quarantine was that it benefited the community. Changing the messaging to focus on community benefit increased the number of people who reported that other households in their area were complying with quarantine restrictions.

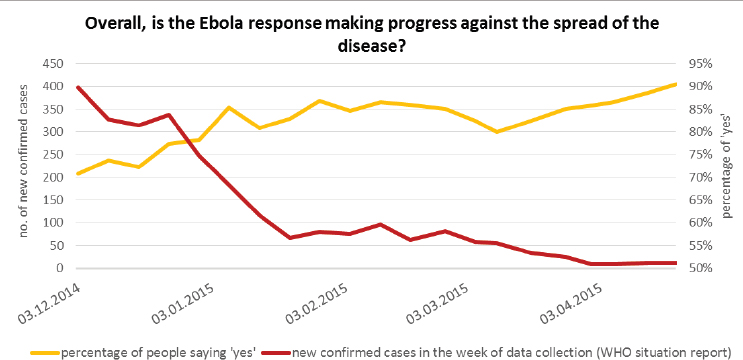

In a survey of the general population of Sierra Leone, the GTS team asked people if they believed that the Ebola response was making progress against the spread of the disease. When data on the number of cases reported were added to the survey response data, the two results correlated well, suggesting that the public’s sense of progress was an indicator of bringing the disease under control, said van Praag (see Figure 4-7). Perhaps not surprisingly, other data from surveys of frontline workers showed that

SOURCE: van Praag presentation, December 13, 2016.

people became less inclined to follow standard Ebola protocols, such as handwashing, as the intensity of the crisis diminished. van Praag also noted that other survey questions on gender-based violence and discrimination after being quarantined showed these were big issues in Sierra Leone. That result led to efforts to try to address these problems related to gender-based violence and discrimination.

In his final remarks, van Praag said this project shows that collecting data, even in a place like Sierra Leone in the middle of an Ebola outbreak, is not complicated. “The key thing is coming out with a strong sampling strategy,” he said. His team has a chief statistician with a Ph.D. in statistics who ensures the data sampling strategies are strong. The other important consideration, van Praag added, is whether good data lead to effective action, and that requires having incentives in place and communicating results effectively. In this project, his team did a briefing every Monday morning, providing all the data with little text but strong visualizations.

Going forward, van Praag noted the importance of interoperability of data, which was not the case in Sierra Leone but that he hoped would be better in future crises. He also said having a transparent culture that welcomes this type of information and uses it to improve areas that are not working well is important, and not to reinvent the wheel every time a crisis strikes. “It took us 4 months to get [to Sierra Leone] because this was not provided for,” said van Praag. “What we need to do is have engagement and communication hardwired into emergency responses, because if you have to put together a team at the last minute and you do not have the financing for it, it is going to be very difficult to get off the ground quickly.”

TRAINING THE TRAINERS

To begin his presentation, Chalaud briefly explained that WFSJ is a nonprofit organization based in 70 countries. Its main work is to build capacity by training journalists, particularly local ones, with different levels of knowledge. WFSJ believes it important, he said, to develop local capacity and to have local journalists train their peers. “Obviously, there has been a lot of training in the last couple of years around Ebola and Zika,” said Chalaud.

WFSJ’s involvement in the Ebola crisis began when the organization started receiving alarming messages from its network of journalists in West Africa. “They were telling us about the poor communication that was heightening apprehension among the public and also seeding confusion among journalists, because obviously in those regions you have very few specialized science health journalists,” said Chalaud. In August 2014, WFSJ conducted an online survey to identify the challenges, better understand them, and get a clearer picture of the overall needs and capacities on the

ground. The survey garnered more than 100 responses and revealed that the major capacity issue was a lack of basic resources, such as solar panels to power a radio station in the middle of a forest, for the journalists on the ground to do their job. WFSJ launched a crowdfunding exercise to raise money and buy equipment for some of the local media outlets. Other gaps described in the survey included

- scant media relations with politicians, researchers, and institutions;

- lack of transparency leading to rumors, disinformation, and misconceptions;

- editorial filters;

- cultural contexts and issues of local languages and religions that led to public service messages being misunderstood;

- no formal specialized training; and

- lack of scientific knowledge.

Chalaud noted that lack of transparency is also causing trouble for clinical trials for the newest Ebola vaccine. Local journalists, he added, have little knowledge about how the trials are being conducted.

Lack of scientific knowledge, said Chalaud, is a barrier to creating a culture of evidence, which is the focus of WFSJ training courses and the toolboxes it helps build for journalists in the global south. The three areas of concentration in these courses include addressing the limited access to evidence, limited capacity to appraise evidence, and limited capacity to translate and communicate evidence in a way that is relevant to the public, as well as to the editors who have to approve stories. Accessing information in middle- and low-income countries is a major challenge, he said, and even when they have online capabilities and can find rigorous evidence online, it is usually in the form of publication abstracts. Most journalists and media organizations working in the global south do not have the funds to pay for full access to scientific literature, and even when the full paper is available at no cost, the authors are invariably located at elite northern institutions. “If you are going to try to better understand the science behind the research, you might want to talk to a local researcher when you are in Angola, not someone on the other side of the planet,” said Chalaud. As a result, he added, “All of this research is of minimal relevance to a lot of low- and middle-income countries.”

To begin addressing these issues, WFSJ started targeting nonspecialized, nonscience journalists after first establishing a cadre of trained local trainers. They built toolboxes to help these journalists understand some of the science and research, dissect jargon, and develop an appreciation for the ethical aspects of covering scientific stories. Working with researchers at Concordia University in Montreal and the Université de Bouaké in the

Ivory Coast, WFSJ has been mapping a typical communication ecosystem in periods of crisis in West Africa to help improve training.

Sustainability is a major issue, said Chalaud. “It is all very good to train people in the periods of crisis, but what do you do to keep them engaged?” he added. To create sustainability, WFSJ is starting to train local researchers as a means of creating a professional link between journalists and the local research community. The organization is also engaging with local civil society organizations because, as he explained, they use scientific evidence and communicate in their own way. “We are trying to see if there is a way between the media and civil society organizations to have a common ground in communicating the evidence,” said Chalaud. WFSJ is now starting to look at approaches to involve editors, including embedding them in local trainings.

So far, the organization has trained more than 100 journalists in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, and at least 7 of those individuals are now full-time science and health journalists. Chalaud said he considers that a major breakthrough. WFSJ is now creating new resources for the trained journalists, including toolboxes on vaccines and dementia, as a way to keep them engaged and expose them to the wider network of journalists from the north who may be working in their part of the world.

Chalaud highlighted what he calls the Swiss army knife, a new set of tools to help connect experts and journalists in the global south and in middle-income countries in the north. This project includes building a mobile phone dashboard app where journalists can sign up and post a professional profile and where the communication departments at research institutions can sign up to connect journalists with experts at their institutions. It also includes developing a learning tool comprising gamified training modules on good practices, data analysis, and reporting, as well as e-books and factsheets. Other components under development include a verification tool that will enable journalists to verify quickly the source of some of the research they may be consulting and a data collection tool to document field-reported incidents. All these tools, said Chalaud, will use an open-source code so that third-party developers can adapt the tool to work in different cultural environments.

Chalaud commented that one last program WFSJ is developing, in collaboration with the First Nations in Canada, will collect citizen reports from isolated and off-the-grid communities. “We are going to try to have citizen reporters in different communities be the linchpin between those communities and the public health agencies in those territories,” said Chalaud. This approach of using trusted sources already in the community as reporters is a different way of investing in science journalists and the journalist community, he noted, and one that could be replicated in various parts of the world.

DISCUSSION

Lonnie King, professor and dean emeritus of The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, remarked that, during a global outbreak, dozens of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) might get involved, and he questioned how it was possible to work with all of them, given their uneven communication capabilities, in terms of an overall communication strategy. Chalaud replied that in West Africa the civil society organizations face the same issues as local journalists with regard to finding accurate information and then channeling it to the local population. As a result, WFSJ is now inviting representatives from civil society and other NGOs to be part of its training along with local journalists. “But again, in a crisis environment, the dynamics are such that even those local, smaller NGOs, like the media, are running around like headless chickens and having to deal with lack of means, lack of money, and so on,” said Chalaud. One finding of the communication ecosystem mapping exercise his organization is conducting was that information in Guinea and Sierra Leone travels through village elders, with the local civil society organizations tagging along. “When you are talking about villages in the middle of a tropical forest in Guinea, the dynamics are pretty skewed,” said Chalaud. “The traditional models we have been discussing here do not apply.”

van Praag noted the international NGOs his organization has worked with have been in the vanguard in terms of their interest in feedback and a desire to understand what the people they intend to protect or assist are thinking. “I have been very encouraged,” he said.

Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, remarked that the news today is all about headlines and that journalism seems to be operating increasingly in the entertainment space compared to several decades ago. Of greater concern, he said, is the trend for news to be mixed in with reality television, making it difficult to distinguish between reality and fiction. Given these trends, he wondered how public health can get its messages, which he characterized as rather dull, into the news when an outbreak is just starting and before it has become an alarming, out-of-control outbreak. “How do you train journalists to make the public health message exciting enough to get on CNN and Headline News?” asked Daszak. Chalaud replied that the responsibility falls among the editors, who need training to help them be more science and health savvy, but Ernst said this is not just the responsibility of journalists and editors. “It is on us in public health . . . to make what we know accessible, to make it interesting,” said Ernst.

Dennis Carroll, director of the Global Health Security and Development Unit at the U.S. Agency for International Development, asked what happened—or did not happen—with communication about Zika that made Zika such a “ho-hum moment” within Congress and what lessons can be

learned to avoid such a response with the next microbial outbreak. Ernst replied that she believed Zika was caught in muddy political waters when politicians learned it could be transmitted sexually and reacted to the potential role that Planned Parenthood might have in mounting any response to the emergence of Zika. “I think that ended up being politically divisive in a way that was not effective, so it ended up being a little less about the actual pandemic and more about politics,” said Ernst. She said she was not certain how to avoid such a situation in the future other than to develop a network of experts, such as the individuals at the workshop, and organize them to mount an effective communication response delivered through communication channels prepared to receive those messages when the next crisis arises.

Eduardo Gotuzzo, director of the Alexander von Humbolt Instituto de Medicina Tropical, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, asked Chalaud how his Swiss army knife approach deals with the cultural determinants that can affect how an outbreak spreads. Chalaud replied that addressing this issue involves dedicating resources to better understand where the science might fit around cultural determinants and how journalists can work within the constraints they impose. He pointed out that the journalists WFSJ trains are part of those communities, and so they tend to be better at handling those cultural phenomena than the trainer who might be coming from another country. One strength of the GTS approach, said van Praag, is that it starts by collecting data from people in affected communities about their perceptions so that it can respond more quickly in terms of delivering messages appropriate for those communities. After this initial step, he added, the feedback process helps improve those messages and strengthen engagement with the community.

Countering the Anti-Vaccine Voice

Daszak commented on his frustration with the anti-vaccine movement. He had just returned from Australia, where poor uptake of a Hendra virus vaccine for horses was triggered by one blogger who reported her horse aborted after being vaccinated. This vaccine is important, he said, because the virus can jump from horses to humans and has caused human deaths. “Have we failed?” asked Daszak. “Did the Australian government fail to deal with that early enough?” Larson responded she had just reviewed a paper on this very subject, and one issue with the Hendra vaccine is that animal owners have little trust in veterinarians when it comes to vaccines. She said it may have been possible to listen earlier to concerns among horse owners and suggested health professionals and veterinarians should receive training on how to deal with difficult conversations to enable them to better address concerns of their clients.

Responding to a question from Gotuzzo about how large organiza-

tions can respond quickly to rumors, Maron said it is essential to address slowdown points such as the need for legal and institutional signoffs from multiple individuals or departments. She added that doing so requires organizational leadership to make streamlining the flow of information to the public a priority and to put emergency protocols in place that the entire organization understands. “This is not to say you should put out incorrect information, but it should say that you have a couple of people that are authorized to speak without 20 layers of bureaucracy stopping them,” said Maron. She acknowledged that establishing such protocols to cover every situation can be difficult, but regardless, such discussions should happen ahead of time, and the public affairs team should make them happen.

Larson responded to a question about how to address the problem of health care professionals giving out bad advice about vaccines, either because they are misinformed or they have an anti-vaccine attitude, by noting the value of understanding who these professionals are in the same way that it is important to understand the different segments of the public. In her opinion, many of the professionals and members of the public who are reluctant to vaccinate are merely uncertain about vaccines and are not “hardliners.” Uncertainty, she said, is something that education and outreach can address. Maron added that she has talked with scientists about this subject and many raised the need for more continuing education courses and more education earlier in training on how to talk to patients about vaccine issues. Many of the scientists also called for professional societies to issue regular updates about vaccine efficacy and safety.

Enriqueta Bond, retired president of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and founding partner of QE Philanthropic Advisors, asked if there is a well-organized system to address the long history of anti-vaccine sentiment or if there is a need to build a larger coalition to do so on an ongoing basis. Larson replied that there are efforts ongoing in this area. The WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts, for example, has become so concerned about vaccine hesitancy that it established a separate advisory group to deal with anti-vaccine sentiment. Over the past 5 years, she said, there has been a growing literature on the drivers of these behaviors, but the field is still missing good strategies to deal with those drivers. In her opinion, current methods of enacting large-scale vaccination programs are good at creating demand for the first 80 to 85 percent of the population. What is needed, she said, is an entirely different approach for the remaining 15 to 20 percent of the population. She and various colleagues are trying to develop these new strategies.

Working with the Media

George Poste, chief scientist of the Complex Adaptive Systems Initiative and Del E. Webb Chair in Health Innovation at Arizona State University, commented on two vastly different responses in the U.S. media to infectious disease outbreaks: the media being “entirely complicit in the spread of panic” in reaction to eight cases of Ebola in the United States and the lack of media attention to the more than a million cases of chikungunya in the Caribbean basin. “Why do the U.S. media, and I’m generalizing, seem to be so unable? Is it simply because schools of journalism are now schooled entirely to stoke crisis and controversy?” he asked. Maron replied that Poste was right in saying he was generalizing about the media because she has the luxury of writing for Scientific American, whose readers are particularly interested in science and more sophisticated when it comes to the complexities of these stories.

That said, Maron did not think it is fair to say the media following the few Ebola cases in the United States made no effort to communicate more clearly what the risk was in this country. One problem, she said, was that the response to rumors was too slow. In her opinion, health officials should have held press conferences and conducted a social media campaign as soon as the first rumors started circulating, and perhaps even a Twitter question-and-answer session that allowed the public to ask questions and get an immediate response. “I think that people had real worries and they did not know where to look to get answers,” said Maron. In this case, the public health community’s approach of posting information on websites and expecting people to go find it was not sufficient for assuaging public fears.

Going forward, she suggested the public health community should think more about the allies it needs to make. It might be worthwhile during a future infectious disease scare to conduct a question-and-answer session live on television or a top media publication as soon as possible and to work with some less conventional partners, such as celebrities, people with large Twitter followings, or someone popular on YouTube, to get correct information out quickly and widely to the public. She said she was not suggesting making those less conventional partners into authorities, but to use them to spread real information via retweeting or posting on widely followed Facebook pages, for example.

In the case of chikungunya, Maron said her publication has covered this disease, again because the magazine’s readership is interested in it. In her opinion, the mainstream media are not that interested because chikungunya does not have the same scare factor as Ebola. “When people think about joint pain, even longer-term joint pain, they do not think about it being crippling and keeping you from going to work, and they do not

think about long-term headaches that might keep them from picking up their kids,” said Maron.

Jeffrey Duchin, health officer and chief of the Communicable Disease Epidemiology and Immunization Section for Public Health in Seattle and King County, Washington, asked for advice on how to work most effectively with journalists and other media sources in the event of an acute infectious disease outbreak, and in particular, how to manage the distrust of experts that exists in some populations. Maron said three important considerations when working with journalists are to be upfront about the limits of one’s knowledge, to think about what you want the take-home message to be, and to be able to suggest other sources of information journalists might want to check. When considering who to talk to given that nobody has an infinite amount of time to spend speaking with journalists, she suggested thinking about which audiences are most critical to reach at that moment. If the issue has something to do with young children or fetal abnormalities, the mommy bloggers Kreps mentioned might be a prime outlet. If a key audience is one driving home from work, radio might be a good place to start. She also recommended working with the media affairs office and cultivating relationships with a few journalists.

Other Avenues for Information Dissemination

Larson commented on the importance of reaching out to trusted leaders in communities during quiet times to form the relationships that will be significant during disease outbreaks. These leaders are not necessarily the obvious choices, such as the mayor or other official, she said; they are more likely to be peers in the community. With the HPV vaccine, for example, mommy bloggers would be trusted leaders, but so might a teenager active on Facebook who is trusted by her peers. She suggested tapping into CDC’s extensive nationwide network of community leaders and focusing on those communities where there has been a lower level of uptake during previous public health crises. Maron agreed completely with these suggestions and offered one more: “Meet people where they are at in the sense that if you are willing to share and humanize yourself to say ‘Yes indeed, I had my children vaccinated,’” said Maron.

David Relman, the Thomas C. and Joan M. Merigan Professor at Stanford University, commented on the need to think carefully about how to take advantage of technology and use it to communicate more effectively with the public. Maron replied that the high degree of fragmentation in the alternative media world makes this a challenge. As a case in point, she said that while she may have thousands of people following her on Twitter or Facebook, that is a very specific subset of people. Meanwhile, the tens of

millions of people who are not following her are looking for information from other sources. “So at the same time that there is a lot of noise being introduced, there is also a lot of choosing taking place,” said Maron. The only solution currently is to identify and work with “amplifiers,” people who have a giant following who might retweet or repost credible information. “I think that is the way you can leapfrog into a bigger field and reach people you might not have otherwise reached,” said Maron. She used Chelsea Clinton as an example of a person who retweets science and health information often. She noted, too, that trainings are now available for scientists on how to use social media.

Maryn McKenna, an independent journalist and author, pointed out that major corporations all have social media teams that function essentially as crisis communication teams. During quiet times, these teams monitor social media streams for mention of their company so that when something happens or something negative about the company appears, they are ready to respond immediately. The problem is that public health does not have the money to follow this example. Compounding this issue is the fact that public health wants, for good reasons, to be trusted and correct, which mitigates against being nimble.

McKenna then asked Maron how public health agencies could have acted differently in the first few months of the emergence of Zika that would have made her job easier. First, said Maron, public health did not allow for enough uncertainty when first talking about Zika. “They were very definitive in their comments saying it is only mosquito-borne and not sexually transmitted, and they did not even mention a report in the literature [Foy et al., 2011] of one instance where a gentleman thought that he had sexually transmitted Zika to his wife when he was doing field work in Senegal and came back to Colorado,” said Maron. She said it also bothered her that CDC would not share information about prior Zika cases dating back to 2007, which was what prompted her to call state health departments for that information. In addition, the states were releasing information about local Zika cases but referring reporters to CDC for more information, and CDC was sending them back to the states. “That led to a slowdown and some confusion,” she said.

Responding to a question about whether confidence is playing a bigger role than individual behavior in setting policies, Larson said that confidence has to exist at three levels: the product, the provider, and the policy and politician. The confidence index she and her colleagues developed (Larson et al., 2016) attempts to integrate these factors. Using this index, they found an absolute correlation between high levels of confidence in the health system and lower vaccine hesitancy.

Communication as a Surveillance Tool

Stephen Johnston, professor of life sciences and director for the Center for Innovations in Medicine and of the Biological Design Graduate Program at The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, asked if there is a way to turn the communication tools discussed at the workshop into an early detection system, either by picking up informative rumors or by building more capacity in Central Africa or Southeast Asia, areas that are likely to be the sources of the next infectious disease outbreak. Ernst replied that the potential does exist to do just that and that there is some precedent. Google Flu Trends and Google Dengue Trends are two examples of programs that mine Internet traffic to spot emerging infectious disease outbreaks. She noted, though, that there is a big gap in the response that occurs after acquiring that evidence. “I think we need a larger body of work that demonstrates that these are effective ways to pick up real outbreaks and real trends,” said Ernst. In her experience speaking to public health officials about her system, she explained, they want to know that it works, to see proven results to show the data are reliable, before they start leveraging scarce resources to address what may be an emerging outbreak.

McKenna asked Ernst how her app was different from the Who Is Sick and Flu Near You apps, both of which have engaged the public but are nonspecific and self-selecting. The primary difference, said Ernst, is that she designed her application specifically to detect Aedes-borne diseases, which eases the problem these other apps have in detecting a broader range of symptoms. She said that, although she believes there is a limit to how many people can engage with all these different syndromic platforms, if the developers of these different platforms will cooperate with one another, it should be possible to have them feed into each other. “If you can identify syndromes that are being reported into Flu Near You or Who Is Sick? and shuttle those down to a more specifically tailored application such as Kidenga, which is really focused on a specific disease cluster, you then push out very tailored information based upon what people are reporting into these larger systems,” said Ernst. She acknowledged that doing so will require a great deal of networking and buy-in from the different development teams, but she believes doing so is possible.

Getting Ahead of the Next Epidemic

Poste commented that the public health community should be better prepared to answer questions from Congress about how it will spend the funds to be prepared ahead of time to mount a crisis response. “What we lack is a completely cogent overview of what we are actually going to invest to deal with this in a proactive way,” said Poste. “There is no broad plan

for how we should optimally allocate these new billions that are needed.” In that regard, said Frank Smith, managing director of Management Sciences for Health’s No More Epidemics campaign, the community needs to continually “ring the bell” between events to promote policy change to support additional preparedness funding. “I would encourage all of you to work with us in the No More Epidemics campaign, to join this community and try to see if we can influence governments and keep this issue on the political agenda so we are not going from event to event, but are trying to address the systemic failures that lead us to one of these events,” said Smith.

Rima Khabbaz, deputy director for infectious diseases and director of the Office of Infectious Diseases at CDC, noted that when the Institute of Medicine released a report more than 20 years ago on emerging microbial threats (IOM, 1992), Congress allocated a small amount of money to build a limited public health capacity, but Congress never committed the funds to the public that the report said were needed to be proactive. “Since then, it has just been the disease du jour,” said Khabbaz. When West Nile appeared, for example, some resources were available but they largely dried up as public attention waned, she said. She noted, though, that the Global Health Security Agenda resulted in some resources becoming available to create systems and infrastructure to detect microbial threats and respond earlier.

This page intentionally left blank.