6

A Systems Perspective on Strengthening Risk Communication and Community Engagement in Disease Outbreak Response

The workshop’s final session featured two presentations that discussed the international normative aspects of risk communication as they pertain to the International Health Regulations (IHR), the gaps in improving coordination mechanisms that can support preparedness and enable more predictable and effective responses to infectious disease outbreaks, and the capacities that may be needed to implement these frameworks for communication. The two panelists were Gaya Gamhewage, head of interventions and guidance in the Infectious Hazard Management Department of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Health Emergency Program, and Erma Manoncourt, founding president of M&D Consulting and retired United Nations official.

RISK COMMUNICATION AS A CORE CAPACITY UNDER THE INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS

The 21st century poses new and fast-moving challenges for emergency risk communication (ERC) thanks to the relative ease of international travel, the proliferation of mobile phones and other avenues of communication, and the development of technology to create new microbes, said Gamhewage. Lessons learned from recent epidemics can direct, at least in part, future preparedness planning, but she cautioned that not every lesson from the past fits the future and agreed with Kreps’s earlier statement that proven strategies can inform future actions, but the specific tactics will likely change for each outbreak.

To Gamhewage, ERC is about an exchange of facts, opinions, and

views between those who know or who are responsible to act and those who are at risk. The key point, she said, “is when you are the authority and expert and you are also at risk, that is the moment you realize what you say as an expert does not really matter to you as a person at risk.” For her, that moment came when she was working with the response team in Sri Lanka following the 2004 tsunami and realized 50 members of her extended family had perished. “Your perspective in responding when you have personal loss and personal risk is very different from when you are sitting in Atlanta or Geneva or DC,” she said.

Gamhewage noted that the purpose of ERC is not simply to tell people about their risk, but about giving them enough contextualized and appropriate information to make their own informed decision, which could be to ignore the expert advice. ERC, she added, covers a wide range of domains ranging from mass communication to community-level dialogue and community engagement. WHO looks at ERC as a form of health promotion in which the individual is seen as being part of a family and community and interacting with systems and services in political and legal frameworks. In the event of a public health emergency, public information disseminated through the communication channels preferred by various populations triggers mass mobilization of affected and at-risk communities. In this framework, the public health system engages individuals, families, and communities through community influencers who can also provide trusted information and address rumors. The desired outcome, then, is that everyone at risk is able to make informed decisions to mitigate the effects of the threat or hazard, which in the case of an infectious disease outbreak would be to control an epidemic as quickly as possible. She added that, during epidemics and pandemics, risk communication can intervene at every stage of the outbreak, including at the animal–human interface.

In discussing the relevant international frameworks, Gamhewage pointed out that the WHO constitution, created in 1948, had the foresight to see a world that respects human rights, that appreciates connectivity, and that values participation of the public as central to dealing with health problems. IHR, revised in 2005 after the first outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), has its roots in the first wave of globalization that saw diseases carried from Asia and Africa back to Europe, and it includes risk communication as one of eight core capacities for responding to and mitigating the international transmission of diseases. Also relevant, said Gamhewage, is the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework, whose main purpose is to settle issues of international property rights related to novel influenza virus strains but that also includes pandemic risk communication as one of five preparedness areas. In addition, there are program strategies for outbreak response, humanitarian action frameworks, and vaccination efforts.

Lessons Learned from Prior Epidemics

A number of lessons have been learned from the past few big epidemics, including the SARS outbreak in 2003, the Ebola outbreak in 2014, and the outbreak of yellow fever in Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2016. These lessons, Gamhewage laid out, include the following actions:

- Create and maintain trust, and communicate even when uncertain.

- Communications should be outcome based, not message based.

- Be first, be fast, and be flexible.

- Listen to, involve, and engage those who are affected rather than simply telling them what to do.

- Use integrated approaches and social science techniques to listen to communities, understand their perceptions and barriers to action, identify enablers, and cocreate solutions that work for those communities.

- Coordinate activities among all partners and across all sectors and levels and avoid ego-driven battles to control risk communication activities.

- Build national capacity and support national ownership, including among top leadership.

- Assess capacity and test that capacity through exercises, given that people who train together and do simulation exercises together work better together.

With regard to system capacity, Gamhewage listed 16 types of communication for which expertise is needed (see Box 6-1), and she noted that no one person can be skilled at all of them.

To illustrate the complexities of risk communication, Gamhewage recalled speaking to a stadium filled with 15,000 teachers in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, who were there to learn how to reopen the nation’s schools after the Ebola crisis had passed. Sitting at the back of the stage, she watched as two people from the Ministry of Education demonstrated how to put on and take off personal protective equipment, leaving 15,000 teachers thinking they have to use personal protective equipment to open schools. “The agenda was thrown out and the Minister said, ‘You go on and sort this out.’” Gamhewage, who was not scheduled to speak at all, had 5 minutes to get 15,000 teachers to unlearn what they had seen and to explain that they needed their brains, not personal protective equipment, to reopen the schools.

At a November 2015 gathering of 60 stakeholders convened by WHO to review what took place during the Ebola outbreak, those attending

agreed on seven lessons (see Box 6-2), many of which had been previously noted during the workshop. What worked during the Zika outbreak, Gamhewage said, was that the global, multipartner coordination strategy was able to mount a response quickly, within the first 2 to 3 days of receiving an alert. For the first time, she said, half the global response budget was allocated for risk communication and community engagement, which enabled the development of mobile communication applications and other informational resources for use in community engagement. Similarly, for the response to the 2016 yellow fever outbreak, risk communication, and community engagement were an integral part of the response strategy, and funds were allocated for operational capacity and social mobilization.

International Health Regulations

IHR, Gamhewage explained, is an agreement among all the countries of the world that authorizes WHO to receive information, investigate reports of outbreaks, declare public health emergencies of international concern, and direct travel restrictions. IHR requires that all WHO member countries

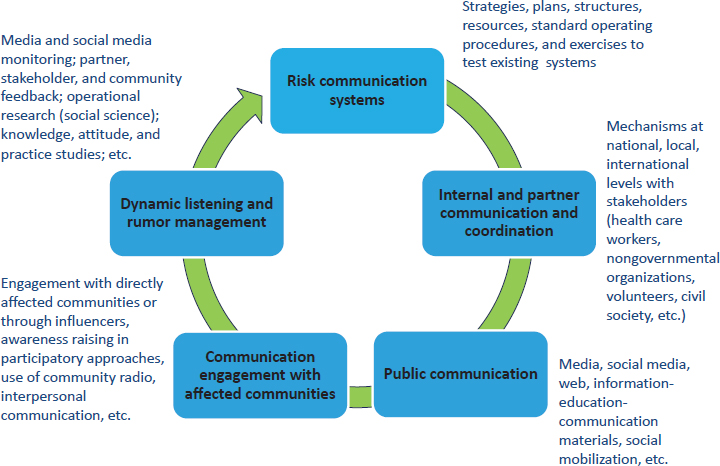

detect infectious diseases, assess the risk from any appearance of disease, report to the rest of the world, and respond to public health threats with the aim of helping the international community prevent and respond to public health risks. Risk communication capacity is among the eight core capacities required by IHR, but for many years the member states assessed their own abilities to engage in risk communication. Often, Gamhewage said, the results did not reflect the true level of implementation. In 2016, the regulations were changed to require exercises, after-action reviews, and joint external evaluations to assess communication capabilities by using an integrated systems model for assessment. This model includes five domains: risk communication systems, internal and partner communication and coordination, public communication, communication engagement with affected communities, and dynamic listening and rumor management (see Figure 6-1).

By the end of 2016, 20 countries had completed joint external evaluations, 15 had scheduled them, and 36 had expressed interest in conducting one. The United States, said Gamhewage, volunteered to be first to set an example for the rest of the world, and the evaluation found that the United States had underestimated its risk communication capacity.

SOURCES: Gamhewage presentation, December 14, 2016; WHO, 2016a.

To conclude her presentation, Gamhewage listed five recommendations for integrating ERC into national preparedness. First, she said, the field needs to build the evidence base to support a move from what communicators like to do to what works. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), she said, is collaborating on a project to develop the first evidence-based guidelines for risk communication capacity building. Her second recommendation was to involve all stakeholders and all sectors of the government in capacity building, not just health care or agriculture. She also recommended that risk communicators need to show decision makers the cost of not investing in risk communication and that effective risk communication requires specific skills and datasets. Her fourth recommendation was to evolve national preparedness from a sole focus on technical and biomedical excellence to one that includes social and operational aspects, such as having the capacity to train tens of thousands of frontline responders. Finally, Gamhewage stressed the need for money and people to put all these recommendations into action. For its part, WHO is investing in translational communications and knowledge transfer, developing surge capacity, creating guidelines and a framework for ERC, and participating in joint evaluation exercises.

STRENGTHENING RISK COMMUNICATION: COORDINATION AND LEADERSHIP

At the time of the Ebola outbreak, risk communication was largely viewed in the context of community engagement and behavior change, said Manoncourt, but during any outbreak or emergency, risk communication has to interact with other technical components of that response. In her opinion, she said, interacting effectively requires strong leadership and coordination, enhanced technical capacity with systematized technical guidance, improved data and strategic information systems, and sufficient institutional resources.

During the Ebola crisis, the social mobilization and community engagement effort, cochaired by ministries of health and UNICEF, included some 100 partners who met weekly to plan and strategize. A critical aspect of coordinating the activities of these partners was building trust and creating transparency among the partners. When this coordination effort worked well, the partners had the opportunity to exchange information and best practices, producing a better understanding of the collective perception of what worked and how to move forward, said Manoncourt. A key part of this effort, she added, were the coordinated activities at the district and subnational levels that drove the engagement with communities and individuals. An unusual aspect of the Ebola response was that the risk communication team had regular meetings with epidemiologists and clinicians to design strategies for intervening in the outbreak. She also noted that the Global Polio Eradication Initiative engages in similar coordinating activities at the national and district levels, though those meetings only involve the communication and community engagement partners.

With regard to enhancing technical capacity, Manoncourt said increasing surge capacity at the national, regional, and international levels is key. During the Ebola crisis, the communication teams in many countries began calling on practitioners from other sectors, such as teachers and workers from the water sector, to help with risk communication. Forming in-country academic and corporate partnerships could be one approach for developing surge capacity that would benefit from involving experts with local knowledge, but whatever approach a country takes, noted Manoncourt, it should be detailed in a national capacity development plan for frontline workers, supervisors and managers, and policy makers and decision makers. Manoncourt said that, during the Ebola outbreak, nongovernmental organizations put much of their energies into training frontline workers, which enabled other partners to work with decision makers, managers, and supervisors. She also added that the need to bolster leadership capacity was readily apparent during the Ebola crisis. Liberia, she said, had Reverend

Sumo in charge, but there was no equivalently able leadership in Guinea or Sierra Leone.

One aspect of strengthening risk communication is clarifying who the communicators are during an outbreak. The tendency, said Manoncourt, has been to think about health professionals and social mobilizers as the communicators. During the Ebola crisis, however, it became clear that the safe burial teams, the case managers at the Ebola treatment units (ETUs), and the individuals who traced contacts with those diagnosed with Ebola were all risk communicators because they were engaging with the community. The same is true, she noted, during polio outbreaks, when the social mobilizers are not the only risk communicators. “You had to talk about the polio program manager and even more so, the vaccinators, because they were the people who made first direct contact with people in the community,” said Manoncourt.

Another key step in strengthening risk communication capacity is to develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) and preparedness training programs, she added. Manoncourt explained that SOPs are important because they move discussions away from theory to practical application, but SOPs are only as good as the training people receive to follow them. Technical advisory committees can help develop and review SOPs and provide feedback on proposed strategies and tactics. Manoncourt noted that the Global Polio Eradication Initiative has done a good job at developing SOPs and has provided an example for Ebola and Zika planning to follow. The polio initiative created a global communications toolkit comprising four manuals that walk individuals and teams through what they need to do during an outbreak and who is responsible for specific actions. Spelling out those responsibilities, added Manoncourt, enables partners to see what their exact role in a response should be and can reduce infighting among partners.

Independent monitoring and outbreak assessment are important for improving data and strategic information systems, said Manoncourt, which is something the polio program has done well during vaccination-related outbreaks. She recommended engaging anthropologists and social science researchers at the national level to be involved in this process. She also noted the importance of community monitoring, and commented that such monitoring was done well by using mobile phones and texted questions during the Ebola outbreak. One reason using mobile phones was possible, she added, was that the risk communication team involved the national telecommunication companies, which allowed people to have access to the service without financing.

Manoncourt reiterated the need to bring other government sectors into the risk communication process. The polio initiative has ongoing programs to link the immunization effort to child health in general, for example. She

also said it is important to look at what communities themselves are willing to offer once they realize what they have available in their communities. With Ebola, for example, some communities got involved by helping to build ETUs.

Manoncourt discussed some of the bottlenecks in ERC. The lack of consistent policy direction and guidance, even with SOPs, can cause confusion and frustration. Staff turnover at the senior level is an issue at all levels of government worldwide. “Today, you have somebody who believes in what is going on and they support it, and tomorrow you get somebody else and support goes away,” she said. Another issue she has seen in all the interventions in which she has been involved is the tendency to top off salaries to the point that people do not see these “extra” duties as part of their job. An extreme example occurs when workers are not paid and lose motivation to help. In many of the ministries, Manoncourt explained, the health promotion department is likely to have the least power, and in most governments the Ministry of Health, like the Ministry of Education, is weak as well. This lack of power creates a challenge of how to appeal to the finance officials to fund these efforts.

The last point Manoncourt highlighted was the tendency to become concerned when community volunteers want to be paid. “There are no virgin communities anymore,” said Manoncourt. “Everybody has seen everybody else come in and get monies for the work that they are trying to do, and yet we are saying we want you to come out and do it on behalf of the community.”

DISCUSSION

Jay Siegel, chief biotechnology officer and head of scientific strategy and policy at Johnson & Johnson, commented that the U.S. government seems to lose interest in an outbreak once the emergency is gone, and as a result, long-term funding for capacity building and preparedness is always an issue. He asked the panelists if this was a global problem, and both Manoncourt and Gamhewage said it is. Manoncourt said the groups she works with are trying to position risk communication as part of a nation’s health infrastructure, not something extra that is added on when there is an outbreak. Gamhewage added that donors seem to have little interest in this kind of work, and policy makers in developing countries ask why they would invest in risk communication when they cannot afford epidemiologists or laboratory workers. She has, however, seen approaches that work. One has been to take advantage of the window of opportunity that opens immediately after an outbreak, when the value of risk communication is most apparent. Another approach is through bilateral agreements between countries that stress risk communication. A third approach, she said, is to

have decision makers run a desktop simulation exercise to see the capacity gaps themselves.

Responding to a comment Gamhewage made that IHR has no teeth and was low on the global agenda, Jeffrey Duchin, health officer and chief of the Communicable Disease Epidemiology and Immunization Section for Public Health in Seattle and King County, Washington, asked if there was enough global core capacity for risk communications. After noting there are only two pieces of international law for health—IHR and the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control—Gamhewage said that since the Ebola outbreak, the world community has become more serious about IHR and risk communication. The Global Health Security Agenda, which launched in 2014, is focusing on and investing resources in joint external evaluations and national action planning. The challenge, she said, is to involve experts in these evaluations who are not just field practitioners but who can go toe-to-toe with ministers and presidents and resist the pressure to change findings so they shine more favorably on a country.

Lonnie King, professor and dean emeritus of The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, noted that the World Organisation for Animal Health has conducted a veterinary assessment for capacity to respond to outbreaks in more than 104 countries that has been used to obtain resources to address gaps and shortcomings. The private sector, he added, has been providing some of these additional resources. Manoncourt said ministries are using the polio initiative’s assessments to strengthen their argument for funding to build capacity. She added that country-to-country comparisons can also drive increased funding because there is some level of competition among countries.

Manoncourt said one issue that has not come up during the workshop was the need for collaboration between U.S. and European academic institutions and those in developing countries. There was a time, she said, when there was a great deal of exchange of expertise and competencies, but she is seeing less of that today. “That is unfortunate because it was a nice way to aid a country internally developing their own capacity but using the input and expertise from other places,” she said. This type of development was particularly important in the risk communication area, she said, because many countries do not have communication departments in their universities. Gamhewage added that academic collaboration could also generate the data and evidence to support efforts in less developed nations. “One of the reasons decision makers are not investing in this is they feel it is soft and arbitrary,” she said. This tendency is even true, she said, at WHO, where “communication problem” is a catchall for a variety of unresolved issues. She noted that countries do pay attention to WHO guidelines, which go through a thorough review process, and she expects the communication guidelines that will be published in 2017 will be a valuable tool to show

governments the evidence for what works in the area of capacity building for response.

To conclude the discussion, Rafael Obregon, chief of the Communication for Development Section of UNICEF, said IHR is the only binding instrument that makes a specific reference to risk communication, and it therefore provides a “tremendous entry point to strengthen an area of work that I think we all agree is extremely important.” The question, he said, is how to strengthen and leverage IHR to make it more visible in the work that governments do. He noted that UNICEF is working with WHO and other partners to look at influencing the global humanitarian architecture to include risk communication and to detail who is responsible for what activities.

This page intentionally left blank.