2

Perspectives on Building Communication Capacity to Counter Infectious Disease Threats

To provide some context for the workshop’s presentations and discussions, John Rainford, director of The Warning Project; Maryn McKenna, an independent journalist and author; and Stefano Bertuzzi, chief executive officer of the American Society for Microbiology (ASM), provided their perspectives on the challenges and opportunities in communicating infectious disease threats to the public in a manner that protects public health.

BUILDING RISK COMMUNICATION CAPACITY: CAN IT BE DONE?

People such as Rainford who work to build risk communications capacity repeatedly experience the incredible difficulty of balancing the tensions between excellent ideas and the translation of those ideas into a system that can provide reliable information to the people who need it. One of the tensions, Rainford explained, arises because the multiple audiences for risk communication have different ideas about what kind of information is important and how they understand that information. As an example, he laid out a scenario in which a health organization has learned there was a serious problem with a single small batch of measles vaccine. The director of the health organization might be most worried about this news having a negative effect on an ongoing measles vaccination campaign and on broader public confidence in vaccine-based programs, but a mother is more likely to worry about the potential adverse reactions her child could experience from the vaccine. “You have this dynamic in terms of what the

director wants to say and what the mother needs to hear,” said Rainford. Although many people would agree that the proper target audience for risk communication would be the mother, the typical output from such a risk communication effort would be written at a level that the director and his or her colleagues can process, but perhaps the mother cannot.

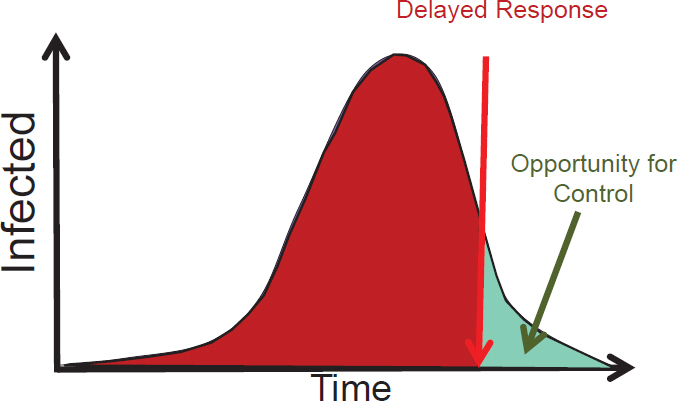

Deciding on the timing of when to engage in risk communication creates another tension, one between effectiveness and caution. A typical disease outbreak, Rainford explained, proceeds along an epidemiologic curve, and as the delay between outbreak and risk communication lengthens, the opportunity to control the outbreak grows smaller (see Figure 2-1). With an immediate response to the first signs of an outbreak, the opportunity for control is large. However, when Rainford asks audiences if they would communicate a serious emerging risk when the potential is first identified or when all of the details are confirmed, 70 percent of the people say they would wait until the full details are confirmed. He did note, however, that he is starting to see an attitudinal shift on this point. The World Health Organization (WHO), for example, recently declared that the Zika virus is guilty until proven innocent of causing birth defects. “This is a step forward,” he said.

Although guidelines, policies, techniques, trainings, and professional norms and standards are the foundations of capacity building, Rainford said he also wanted the workshop participants to consider some “softer”

SOURCE: Rainford presentation, December 13, 2016.

dimensions of risk communication. One dimension is performance measurement, in which the “softness” comes from how one defines success or failure. As an example, he discussed the work he did as part of Canada’s response to an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. “We failed at so many levels and were criticized at such an extreme level,” said Rainford. However, when the government asked 10,000 people in Toronto to go into self-quarantine, they complied. Was that risk communication effort a success or failure? The answer, he said, was that the public’s trust in the government was never broken, and although criticism was substantial, the real performance measure was whether the public followed the government’s guidance. The lesson, he said, is that “we need to consider carefully what success and failure might be.”

Other soft dimensions involve striking the right balance between knowledge generation and knowledge translation and convincing leadership of the strategic advantage of better risk communication. “We see so often in capacity building that we generate systems, models, techniques, and guidelines—they bubble up through the system, they get to the corner office, and they stop because those people are not on board,” said Rainford. As a final thought, he considered the question of whether it is possible to build communication capacity to counter infectious disease threats. “When we ponder, and we will over the next day and a half, how central communication of risk is to success, to protecting our people, to achieving our goals, it sounds a bit corny, but it is really not, can it be done—it has to be done,” said Rainford.

POTENTIAL CHALLENGES FOR ACHIEVING SUCCESSFUL COMMUNICATIONS FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASE THREATS

The recent West African Ebola outbreak was centered in three countries—Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—with 10 cases reported in the United States. Eight of those individuals—seven medical or relief workers and one journalist—were infected outside of the country, and one of those eight infected two additional health care workers in the United States. McKenna explained that the low risk of the disease spreading to the public did not stop some unusual Ebola-related incidents in the United States, including the following:

- Boston, Massachusetts, closed a subway station when someone called 9-1-1 and reported a Liberian woman hemorrhaging on the platform. In fact, she was Haitian and was vomiting.

- The Greenville County, South Carolina, public school system announced it would screen every new student for Ebola before allowing the students to enroll in school.

- In Hartford, Connecticut, a family had to file a lawsuit to get their third-grade child into school after the school banned the child because the family had taken a trip to Nigeria, which lies five countries away from where the Ebola hot zone was located.

- In Rochester, Minnesota, emergency medical personnel arrived to help a flu victim from Somalia in full biohazard gear because the dispatcher could not tell the difference between Somalia and Mali; the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had issued a travel warning for the latter.

- The Stokes County, North Carolina, Board of Education forced an assistant principal to stay home for a 21-day quarantine period because she had been to South Africa, which is 5,000 miles south of where the Ebola hot zone was located.

“I’m sorry to say [these incidents] all contain the same lesson, which is not that Americans are bad at geography, but that the mass public was so alarmed by the idea of Ebola that they refused to listen to or could not absorb the details of how you actually contract Ebola,” said McKenna. “Therefore, the public felt a perception of risk of Ebola that was orders of magnitude greater than what their actual risk here in the United States was.” This perceived risk was true, despite many public health authorities, including the directors of CDC and the National Institutes of Health, and widely read and respected journalists, telling the public repeatedly that the public was not at risk for becoming infected with Ebola.

In retrospect, she said, it should not be surprising the public so profoundly misunderstands medical subjects given the persistent belief among sizable segments of the population that vaccines cause autism and that antibiotics can treat viral infections. A Wellcome Trust study based on a series of lengthy interviews with members of the public revealed some of the reasons people persist in seeking antibiotics (Good Business, 2015), including the need to feel validated. “Warnings about [antibiotic] resistance made them feel like they were being manipulated by the authorities,” McKenna explained. She noted the recent election illustrated vividly something that people in the infectious disease world have known for years: consumers of news sometimes feel free to choose their opinions and the facts they believe.

Efforts to communicate risk about infectious disease threats do have one thing going for them, said McKenna. “The public loves scary diseases,” she said. “When we talk about diseases, the public is disposed to listen.” People may draw the wrong conclusions and they may overreact, but they pay attention to officials they believe have authority. The challenge, she said, is twofold. The first challenge is to put people with reliable information into a position where the public will listen to and believe the message they need to hear. The second challenge is to communicate risk and

information in language the public already uses. “This is not the language that we use, that you use among yourselves, or that you use when you are speaking to me and people like me,” said McKenna. Speaking in jargon and insider language is something everyone with expertise in a field does, she said, but delivering messages the public will receive and understand requires resisting that tendency.

PERSPECTIVES OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MICROBIOLOGY

Since 2006, an ASM program has worked on strengthening the capacity of laboratories to detect infectious diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and others in 23 resource-limited countries across sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, said Bertuzzi. This program, which received funding under the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), has trained more than 3,000 individuals on emerging infectious diseases and has mentored more than 300 laboratory staff, benefiting close to 1,000 institutions in the 23 PEPFAR focus countries (IOM, 2013). One of ASM’s goals for this initiative, Bertuzzi added, has been to become the hub of trusted and authoritative information for both health authority directors and the public.

Recently, ASM has been advocating for the nation to establish an emergency fund to address emerging biological threats such as Zika. The purpose of this fund, said Bertuzzi, would be to avoid “reinventing the wheel” every time a new threat emerges, as was the case when Congress tried to find money to tackle Zika. ASM also helped establish the Antimicrobial Resistance Coalition to facilitate communication among agencies, nonprofit organizations, and other key actors. “We take the One Health approach that brings together various environmental, zoonotic, and human components because we are all part of the same ecosystem,” said Bertuzzi. As part of the coalition’s activities, ASM will convene a meeting of health attachés from the embassies in Washington, DC, to offer the organization’s support to develop national action plans for dealing with emerging microbial threats.

ASM is also developing a digital platform on microbiology that will include a section specific to infectious disease threats. The organization’s goal is for this site to be the authoritative and trusted source of information as described by McKenna, one that will provide information that everyone will be able to understand. ASM members will vet the information and contribute commentary for this Micro Now digital platform. A new online magazine, Germ Theory, will have the goal of focusing the microbiology community on the issue of emerging infectious disease threats.

This page intentionally left blank.