Summary1

The 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic in western Africa was the longest and most deadly Ebola epidemic in history, resulting in 28,616 cases and 11,310 deaths in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. The Ebola virus, which causes fever, vomiting, diarrhea, impaired kidney and liver functions, and internal and external bleeding, has been known since 1976, when two separate outbreaks were identified in the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire) and South Sudan (then Sudan). However, because all Ebola outbreaks prior to that in West Africa in 2014–2015 were relatively isolated and of short duration, little was known about how to best manage patients to improve survival, and there were no approved therapeutics or vaccines. There were a few potentially useful agents in 2014 that had been tested on animals, including nonhuman primates, and some very limited Phase 1 studies of the safety of vaccine candidates in humans. Given the nature of Ebola and its high mortality rate (ranging from 25 to 90 percent), it was not feasible to perform further testing of the safety or efficacy of these agents until the emergence of a natural outbreak of sufficient size and duration. The 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic presented such a situation.

The epidemic began in December 2013 when one child in Guinea was infected, likely from contact with bats. The child died in late December, and soon several family members and health care workers also became ill and died. By February 2014, the illness had spread to Conakry, the capital of Guinea, and in March 2014 Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was asked

___________________

1 This summary does not include references. Citations for the discussion presented in the summary appear in the subsequent report chapters.

to help identify the nature of the outbreak. MSF arranged for samples to be tested in Lyon, France, these samples came back positive for Ebola, and the World Health Organization (WHO) soon announced that the outbreak was caused by the Zaire species of the Ebola family. At the time, the WHO confirmed 49 cases of Ebola in Guinea, with 29 deaths. Soon, Ebola cases were confirmed in Liberia and Sierra Leone, and by June 2014 the epidemic was officially the largest in history, with 759 confirmed, probable, and suspected cases, including 467 deaths. The affected countries struggled to deal with the rapidly escalating epidemic and the growing number of patients, and MSF, which was providing the frontline treatment and infection control, warned that the epidemic was “out of control” and that ending the epidemic would require a massive international response.

In the summer of 2014, several international aid workers contracted Ebola and were evacuated to medical facilities in the United States and Europe, given unproven therapeutic agents, such as ZMapp and brincidofovir, and they appeared to survive at a higher rate than did African patients who contracted the virus. While the aid workers’ survival was most likely due to the state-of-the-art supportive care that they received in the countries they were evacuated to, the use of these therapeutic agents sparked a call to make potential therapeutics available to the thousands of African patients suffering from Ebola. The WHO declared the epidemic a public health emergency of international concern on August 8, 2014, and shortly thereafter researchers and stakeholders began discussing whether and how to conduct clinical trials on potential Ebola therapeutics and vaccines; these discussions ultimately resulted in several teams conducting formal clinical trials in the Ebola affected countries during the outbreak. In October 2015, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) was asked by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to review and analyze the clinical trials that were conducted during the epidemic.

STUDY CHARGE AND APPROACH

The National Academies was charged with convening an expert committee to assess the value of the trials and to make recommendations about how the conduct of trials could be improved in the context of a future international emerging or reemerging infectious disease event (see Chapter 1 for the full Statement of Task). Over the course of 10 months, the 16-member committee held meetings in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Liberia, and developed seven recommendations about how to improve the clinical research response in an outbreak situation. The committee’s recom-

mendations focus on both the inter-epidemic period—the time before and between infectious disease events—and the epidemic period itself.

The committee deliberated from February to November 2016, during which time it held three 3-day public workshops in Washington, DC, London, and Monrovia; one 2-hour public webinar; and three 2-day closed meetings. The committee also solicited and considered written statements from stakeholders and members of the public as well as soliciting information regarding the clinical trials conducted by responsible clinical trial teams. Furthermore, the committee conducted an extensive literature review on relevant topics. (See Appendix A for more information on methodology.)

ASSESSMENT OF EBOLA CLINICAL TRIALS

The clinical trials that took place during the 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic were conducted in an atmosphere and on a timeline entirely different from most clinical trials. The fact that the trials were conducted at all is a demonstration of the ability of researchers, regulators, review boards, and communities to quickly work together when the need is pressing—but it was not easy, and there was avoidable conflict along the way. The trial teams should be praised for overcoming the immense logistical obstacles encountered while trying to design and implement trials in West Africa in the midst of a rapidly spreading, highly dangerous contagious disease. The limited health and health research infrastructure, fear, rumors, lack of trust, and supply chain hurdles were just some of the barriers that had to be addressed and overcome. Despite the successes, however, the overall scientific harvest of the therapeutic trials was described as “thin” in a special report in Science. None of the therapeutic trials ended with conclusive results on product efficacy, although the limited evidence from the ZMapp trials did trend toward a possible benefit. Given the resources, time, and effort put into these trials, they were not as successful as they could have been. While the research did yield some new information about Ebola, none of the trials were able to reach definitive conclusions about efficacy, and some of the inconclusive trials may have actually set back the search for safe and effective therapeutics. (See Table S-1 for further detail.)

The results of the vaccine trials were more fruitful. There are two Ebola vaccine candidates that current data suggest may be safe and immunogenic, though further data on safety and efficacy are needed (see Table S-2 for more detail). The Guinea ring vaccination study (this trial was also named; Ebola ça Suffit) showed suggestive efficacy, however, the trial was not designed to document long-term safety and efficacy because all participants were ultimately immunized and the protocol only followed participants out to day 84. The results of the PREVAIL trial, when available, will provide information on the long-term immunogenicity of the two vaccines studied,

| Investigational Therapeutic | Trial Design | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Convalescent plasma |

|

The transfusion of up to 500 ml of convalescent plasma with unknown levels of neutralizing antibodies in 84 patients with confirmed Ebola virus disease (EVD) was not associated with a significant improvement in survival. |

| Favipiravir |

|

Efficacy and tolerance inconclusive. |

| Brincidofovir |

|

Efficacy and tolerance inconclusive due to small sample size. |

| TKM-130803 |

|

Early results from the study, demonstrated that TKM-130803 was not effective in increasing the survival fraction above 50 percent; unlikely to demonstrate an overall therapeutic benefit to patients. |

| ZMapp |

|

ZMapp showed promise as a possible effective treatment agent for EVD, but there were insufficient data to determine definitively whether it is a better treatment for EVD than supportive care alone. |

| Investigational Vaccine | Trial Design | Results |

|---|---|---|

| rVSV-ZEBOV |

Trial 1 (Guinea Ring Vaccine Trial)

Trial 2 (CDC–STRIVE)

Trial 3 (NIH PREVAIL)

|

Overall results from the three trials:

While the ring vaccination study provided some evidence of efficacy, the trial was not designed to document long-term safety and efficacy because all participants were ultimately immunized and the protocol only followed participants out to day 84. From preliminary results obtained from the PREVAIL I trial results, the antibody response peaked 1 month after vaccination and was sustained over the next 11 months, without any clear evidence of decline for the rVSΔG group; 70 to 80 percent of the cohort responded to the vaccination with an antibody response. When the final immunogenicity data become available, the results of the PREVAIL trial will provide information on the long-term immunogenicity of the vaccines, including the one used in the ring vaccination study. |

| ChAd3-EBOZ |

Trial – NIH PREVAIL

|

Vaccine was well tolerated. At 1 month, 87 percent of the volunteers who received the cAd3-EBOZ vaccine candidate had measurable Ebola antibodies; the results show a robust antibody response to the vaccine that is maintained over a 12-month follow-up period and without evidence of adverse drug reactions other than the expected local injecting site reactions. |

| Investigational Vaccine | Trial Design | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Ad26.ZEBOV and MBA-BN-Filo |

Trial – EBOVAC-Salone

|

Initial Phase 1 studies suggest no adverse events. Phase 2 and 3 studies are ongoing. |

including the one used in the ring vaccination study. These differences in the study designs and the value of the information generated highlight the importance of collaboration in future trials (see Chapter 4 for additional detail).

ETHICS OF CLINICAL RESEARCH DURING AN EPIDEMIC

Planning and conducting clinical research during the Ebola epidemic required confronting a number of ethical issues. First and foremost, stakeholders debated whether it was ethical to conduct clinical trials at all in the midst of a public health emergency. Many, including the members of the WHO Ethics Working Group, argued that there was an ethical obligation to conduct research during the epidemic. On the other hand, humanitarian organizations providing care in the treatment units were skeptical of activities that drew effort away from their mission of providing clinical care to the most people possible. Properly designed clinical research is essential for answering questions about disease processes and for evaluating the safety and efficacy of potential therapeutics and vaccines; indeed, for diseases such as Ebola, an outbreak or epidemic presents the only opportunity to conduct such research. The high mortality of Ebola and the uncertainty about how the epidemic would progress produced a sense of urgency to quickly identify effective therapeutics or vaccines. Despite this sense of urgency, research during an epidemic is still subject to the same core scientific and ethical requirements that govern all research on human subjects. The committee identified seven moral requirements that should guide all clinical research including research conducted during epidemics: scientific

and social value, respect for persons, community engagement, concern for participant welfare and interests, a favorable risk–benefit balance, justice in the distribution of benefits and burdens, and post-trial access.

There was a great deal of disagreement among researchers over how clinical trials should be designed during the Ebola epidemic, particularly over whether trials should use randomization and concurrent control groups. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the preferred research design because they allow researchers to directly compare the outcomes of similar groups of people who differ only in the presence or absence of the investigational agent. However, many stakeholders argued that RCTs would be unethical in the context of the Ebola epidemic. The arguments against RCTs were varied, but most were primarily based on one central assumption: that it was unethical and unacceptable to deprive patients of an agent that could potentially prevent or treat Ebola, given the high mortality rate and lack of known and available treatment options.

This committee found, however, that the RCT was an ethical and appropriate design to use, even in the context of the Ebola epidemic. First, at the beginning of the epidemic it was unknown whether any of the potential agents were safe or effective. This position of “equipoise”—genuine uncertainty in the expert medical community over whether a treatment will be beneficial—is the ethical basis for assigning only some participants to receive the agent. If the relative risks and benefits of an agent are unknown, participants who receive the experimental agent may receive a benefit or may be made worse off. Providing the experimental agent to all would expose all participants to potentially harmful effects. Second, some stakeholders argued that communities would not understand or accept RCTs. However, the committee found that while there was a great deal of mistrust and fear within the affected communities, early, respectful, appropriate communication and engagement could, and did, result in community buy-in and acceptance of RCTs. Finally, the committee found that using a randomized control group as a comparator to the group receiving the experimental agent is the most reliable way to determine whether an agent is effective. Other methods of comparison that were proposed—such as using historical data—are unlikely to produce reliable results because of issues with varying mortality rates and differences in supportive care over time. The committee concluded that randomized, controlled trials are the most reliable way to identify the relative benefits and risks of investigational products and, except when rare circumstances are applicable, every effort should be made to implement them during epidemics. The committee notes that randomization can take many forms (i.e., not just simple randomization) and that trial teams will need to assess the context in which they are implementing trials to determine the best form of randomization (further discussed in Chapter 2).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The mobilization of a rapid and robust research response during the next epidemic will depend not just on what happens during the epidemic, but on what happens before or between epidemics. The committee’s recommendations cover both the epidemic and inter-epidemic periods and focus on three main areas: strengthening capacity, engaging communities, and facilitating international coordination and collaboration. Focusing on these three areas will improve the national and international response to the next epidemic. The degree of improvement in the response will be largely dependent on the investments made in research and development (R&D) on diagnostics (which we do not discuss further), therapeutic agents, and vaccines and on the success in identifying promising candidates in these areas to bring forward to human clinical trials when an outbreak strikes. For a disease like Ebola, where experimental human infections cannot be used to facilitate the conduct of clinical trials of investigational products, an outbreak provides the only opportunity to assess the efficacy of drug candidates in patients and assess the protection capability of vaccines.

Strengthening Capacity

The three countries most affected by the Ebola epidemic—Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—were among the countries that were perhaps the least equipped to respond to an epidemic or to support clinical research during an epidemic. They did not have the infrastructure, human resources, or experience to deal with the public health and health care demands of the epidemic, let alone to facilitate research. The committee found that there were six major capacity challenges that hindered and slowed the research response to the Ebola epidemic: (1) lack of clinical experience with Ebola; (2) poor surveillance and laboratory capacity; (3) deficiency of crucial health systems infrastructure and health care workers; (4) small pool of clinical research experts and very limited prior experience in the conduct of clinical research; (5) ethics review boards in the countries that lacked the resources, experience, training, and information management systems that were needed to evaluate a sudden onslaught of clinical research proposals; and (6) lack of experience and expertise in completing the various and complex legal and bureaucratic steps in clinical trial conduct, e.g., contract negotiations.

First, the affected countries lacked experience with Ebola; although there is some evidence that Ebola virus was present in the region before 2014, the countries had not experienced a prior outbreak and certainly not an epidemic of such magnitude and duration. Second, the countries did not have the surveillance systems and laboratory capacity necessary to quickly

identify the source of the illness at the beginning of the outbreak, and, once the epidemic was under way, the lack of surveillance and laboratory capacity continued to impede attempts to monitor and control the epidemic. In order to address this deficiency, the committee recommends that during the inter-epidemic period funders and development agencies should provide resources and assistance for the development of core capacities in low- and middle-income countries. Because clinical research is dependent on a functioning health care system, it is not enough to invest in the research enterprise in the absence of improving the quality of the health care workforce and the facilities in which care is provided. When international assistance to strengthen capacity is involved, it will likely require a combination of sources from the research and the international development/assistance communities.

Recommendation 1

Support the development of sustainable health systems and research capacities—Inter-epidemic

To better prepare low-income countries to both respond to future outbreaks and conduct foundational research, during the inter-epidemic period (as covered in 2005 International Health Regulations [IHR 2005]), major research funders and sponsors (e.g., U.S. National Institutes of Health and comparable public and private research funders) and development agencies (e.g., U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID] and comparable public and private development funders) should collaborate with the World Health Organization (WHO) and regional centers of excellence to

- Assist in monitoring and evaluating the development of national and regional core capacities under IHR 2005 and

- Provide financial and technical assistance to the extent possible or establish a financing mechanism to help build sustainable core capacities at the intersection of health systems and research (e.g., diagnostics, surveillance, and basic epidemiology).

Third, health infrastructures were poor, and there was a major shortage of health care personnel, which was exacerbated when personnel became infected and died as the epidemic progressed. The shortage of workers hindered the countries’ ability to care for patients and to implement infection control measures, especially in the setting of containment and the need to wear personal protective equipment, and to collect patient-level data that could be used to inform treatment protocols in real time. The committee concluded that, while recognizing the challenges of collecting and recording patient data, it is critical to do so in order to document the natural history of the evolving epidemic and to provide clues to better patient management.

The committee developed two recommendations aimed at facilitating data collection during an epidemic.

Recommendation 2a

Develop memoranda of understanding2 to facilitate data collection and sharing—Inter-epidemic

Research funders, sponsors, national governments, and humanitarian organizations should work together with the World Health Organization (WHO) to develop memoranda of understanding during the inter-epidemic period to improve capacity to collect and share clinical data, with all necessary provisions to protect the privacy of individuals and anonymize data for epidemiological research.

Recommendation 2b

Provide resources to enable data collection and sharing—Epidemic

At the start of an outbreak, developed countries, research funders, and sponsors should work together with national and international health care providers responding to an outbreak, to provide the additional resources and personnel needed to enable systematic data collection on routine care practices and outcomes. Data collection should begin as soon as possible, and data should be shared and coordinated in a central database to advance an understanding of the natural history of the disease and of the best practices for standard of care. This information should also be used to inform protocols for clinical trials.

The final three capacity challenges that the committee identified are distinct but interrelated issues. The three countries had a small pool of clinical research experts and very limited prior experience in the conduct of clinical research. Ethics review boards in the countries lacked the resources, experience, training, and information management systems that were needed to evaluate a sudden onslaught of clinical research proposals. Finally, the countries’ lack of clinical research experience and expertise meant that completing bureaucratic and legal requirements took time and delayed the beginning of trials. To address these hurdles, the committee recommends that stakeholders work with low- and middle-income countries during the inter-epidemic period in order to help these countries develop the capacity to quickly negotiate legal agreements and complete

___________________

2 Memoranda of Understanding: Documents whereby parties entering into a partnership agree to an intended common purpose or set of goals. This is sometimes seen as more of a moral agreement rather than a legally binding agreement, and thus it is usually not intended to have the enforceability of a legal document. Although useful as an overarching agreement that sets out the working principles between parties, other written agreements are necessary to create binding commitments.

ethics reviews when an epidemic strikes. In addition to the necessary human capacity, there is also a need to develop clinical trial templates because even a well-resourced country would be challenged if it needed to solve all the design issues necessary to launch clinical trials in the middle of a rapidly evolving and perhaps rapidly concluding epidemic.

Recommendation 3

Facilitate capacity for rapid ethics reviews and legal agreements—Inter-epidemic

Major research sponsors should work with key stakeholders in low- and middle-income countries to

- Build relationships between local ethics boards and entities that could provide surge capacity for ethics review in the event of an emergency situation. Such efforts would include strengthening networks of ethics boards in a region or connecting local and outside ethics boards, agencies, or experts. Memoranda of understanding setting forth who will provide what services and how decisions will be made should be executed in the inter-epidemic period.

- Establish banks of experts in negotiation of clinical trial and material transfer agreements, and other essential components of collaboration, who are willing to offer pro bono advice and support to counterparts in countries affected by outbreaks.

- Develop template clinical trial agreements reflecting shared understandings about key issues such as data sharing, post-trial access to interventions, storage and analysis of biospecimens, and investments to build local capacity.

In addition to the potential sources of experts in ethical review and the negotiation of clinical trial and material transfer agreements within schools of medicine and public health with extensive experience conducting clinical trials in low-resource settings, the nongovernmental organization Public Interest Intellectual Property Advisors, which provides pro bono legal advice to low- and middle-income countries regarding health research and contracts, and the Council on Health Research for Development, through its program on Fair Research Contracting, can be engaged to assist in these efforts, but will themselves require funding resources to participate.

Although the committee focused its capacity recommendations specifically on capacity for research, it acknowledges that public health, clinical care, and clinical research are all important and interconnected components of a strong health system. Building capacity for research cannot—and should not—be separated from building health systems capacity in general, and efforts to strengthen research capacity without improving the general public health and clinical care infrastructure may negatively affect the per-

ception of clinical research activities and undermine their impact. With this in mind, the committee recommends that during an epidemic—and, more effectively, in an inter-epidemic period—building capacity for research be partnered with building capacity in the larger health system in general. This includes strengthening the educational institutions for health care professionals, from physicians, nurses, and midwives to laboratory technicians and public health professionals.

Recommendation 4

Ensure that capacity-strengthening efforts benefit the local population—Epidemic

When the health care services of a population need to be enhanced or augmented in order to support the conduct of research, development organizations (e.g., USAID), international bodies, and other stakeholders should partner with national governments to ensure that capacity-strengthening efforts are not limited to services that solely benefit study participants.

Finally, research systems should be incorporated into these countries’ emergency preparedness and response systems. This committee’s set of recommendations for actions to strengthen capacity for response and research is intended to provide the basis for cooperative initiatives and a rational partition of primary responsibility among national health authorities, the WHO, and other supranational and international partners involved in health care, public health, and R&D for therapeutics and vaccines, including the academic and private sectors; it is now up to these entities to seize the moment to engage and to invest the critical resources needed to strengthen capacity in low- and middle-income countries for the benefit of all in terms of creating national, regional, and global public goods. There is no doubt that a considerable investment in a sustainable manner will be required and that low-income countries have very limited ability to contribute their own funds to the effort; however, these countries still need to be investing partners and to claim co-ownership.

Recommendation 5

Enable the incorporation of research into national health systems—Inter-epidemic

National governments should strengthen and incorporate research systems into their emergency preparedness and response systems for epidemic infectious diseases. The multilateral institutions (the World Health Organization [WHO] and the World Bank Group), regional and international development agencies, and foundations working in

global health should support national efforts by providing expertise and financing.

Engaging Communities

During the Ebola epidemic, there was a great deal of fear, mistrust, and misunderstanding between the affected communities and the national and international response and research staff. Community members feared going to health care facilities for the treatment of Ebola, rumors spread that Ebola was deliberately brought to the region by foreigners, and some people defied government edicts intended to fight the epidemic, such as quarantine. Early missteps in messaging and a lack of engagement with the communities exacerbated the preexisting mistrust and hindered the response to the epidemic. Initial response efforts tended to be top down and did not take into account community traditions and beliefs—for example, mandatory cremation policies countered deeply held religious beliefs. Over the course of the epidemic, communication and community engagement improved, and this resulted in an improved acceptance of and participation in infection control and research efforts. The committee found that the success of clinical research is dependent on the community’s understanding of, engagement in, and sense of involvement and respect in the process of planning and conducting research. The committee recommends that community engagement be prioritized during epidemic responses and that engagement be a continuous and evolving effort that begins at the outset of the epidemic.

Recommendation 6a

Prioritize community engagement in research and response—Epidemic International and national research institutions, public health agencies, and humanitarian organizations responding to an outbreak should engage communities in the research and response by

- Identifying social science experts in community engagement and communications to lead their efforts to effectively engage and connect with communities affected by the epidemic.

- Consulting with key community representatives from the outset of an outbreak to identify a range of local leaders who can participate in planning research and response efforts, help to map community assets, articulate how to infuse cultural and historical context into presentations, and identify gaps and risks in developing public health measures and designing research protocols. Consultations should be continued throughout the implementation phase by relevant actors to provide information as the outbreak evolves, provide feedback about progress and results, and inform and recommend changes to strategies based on feedback from the community.

- Coordinating within and across sectors, with national authorities and with each other to ensure alignment of social mobilization and communication activities with the overall response and research strategies, and that there is sufficient support and training to local leaders and organizations to engage communities in research and response.

This process would no doubt be easier—and less fraught with problems of trust—if, during inter-epidemic periods, stakeholders invested more time, training, research, and funding into developing frameworks and strategies for community engagement and communication about health and public health that could be translated to the circumstances of an epidemic.

Recommendation 6b

Fund training and research into community engagement and communication for research and response—Inter-epidemic

The World Health Organization (WHO), international research institutions, governments, public health agencies, and humanitarian organizations should actively collaborate together to fund training and research for developing frameworks, networks, strategies, and action plans for community engagement and communication on public health and research that could inform and be mobilized during an epidemic.

Facilitating International Coordination and Collaboration

Events on a global scale generally require a global solution, which in turn necessitates international coordination and cooperation. There are no events for which this is more applicable than emerging infectious disease outbreaks, for even when they are in the beginning apparently localized, they can quickly become globalized. During the Ebola epidemic, research and response efforts were greatly affected by the relationships between international stakeholders and their ability to coordinate and collaborate. For example, there were a number of therapeutic candidates available at the beginning of the outbreak that required evaluation for safety and efficacy before they could gain regulatory approval, but the research conducted on these candidates was scattered and disjointed, with no agreed-upon approach for prioritizing the candidate agents, no infrastructure in place to rapidly implement trials, no consensus about trial design, and no coordination of trial locations. As a result, little more is known about the candidates now than before the trials began. If the international community had coordinated its research efforts and research could have been implemented sooner, there would have been a possibility that the trials would have identified a safe and effective therapeutic that might have been

deployed during the epidemic, but more likely would have been available at the outset of the next one.

The R&D of therapeutics and vaccines is a long and expensive process. The process of drug development from bench to bedside is estimated to, on average, take at least 10 years and cost $2.6 billion,3 with the likelihood of eventual licensing at less than 12 percent. Given the length of a typical infectious disease outbreak (weeks to months) and the length of time it takes to conduct drug discovery and assess efficacy and safety (years to decades), the odds that a new compound will be discovered and evaluated during an outbreak is vanishingly small. Therefore, making progress on the R&D of products—including therapeutics, vaccines, assays, and diagnostic tests—during the inter-epidemic period is the only way to ensure that promising candidates are ready for trials once an outbreak occurs. To this end, the committee recommends that an international coalition of stakeholders work during the inter-epidemic period to advise on and invest in priority pathogens to target for R&D, develop generic clinical trial design templates, and identify teams of clinical research experts who could be deployed to assist with research during an outbreak. The international coalition could also discuss and agree on methods to address administrative requirements that would rapidly become high priority during an emerging infectious disease outbreak, such as the location and management of a central data repository.

Recommendation 7a

Coordinate international efforts in research and development for infectious disease pathogens—Inter-epidemic

An international coalition of stakeholders with representation from governments, foundations, academic institutions and researchers, pharmaceutical companies, humanitarian organizations, and the World Health Organization (WHO) (such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) should work on the following planning activities to better prepare for and improve the execution of clinical trials conducted during infectious disease events:

- Advise on and invest in priority pathogens to target for research and development, and promote a process to ensure that, whenever possible, interventions should be brought through Phase 1 or Phase 2 trials prior to an outbreak.

- Develop generic clinical trial design templates for likely outbreak scenarios. The reasoning and rationale behind the designs and the situations in which each would be best utilized should be discussed with representatives of ethics review boards, major humanitarian

___________________

3 The cost for developing a licensed product.

- Develop a list of key experts in clinical research from different agencies and organizations who could be rapidly seconded to the coalition of stakeholders and deployed anywhere in the world when an outbreak is first identified.

organizations, and at-risk local communities to promote buy-in from stakeholders in advance of an outbreak.

In addition to cooperating and collaborating in the preparation for an epidemic, it is essential that the international community coordinate its research efforts once an outbreak begins. Outbreaks of infectious disease can evolve, move, and end quickly; it is critical that well-designed trials of the most promising agents be implemented as soon as possible in order to maximize the likelihood of finding a safe and effective therapeutic or vaccine. To that end, the committee recommends that in the event of an emerging epidemic, an independent rapid research response workgroup should be convened by the international coalition of stakeholders. This workgroup would have the requisite expertise in order to appraise and prioritize products for trial, determine which trial designs are best suited for the circumstances, and monitor and evaluate the trials.

Recommendation 7b

Establish and implement a cooperative international clinical research agenda—Epidemic

In the event of an emerging epidemic the international coalition of stakeholders (in Recommendation 7a) should designate an independent multistakeholder rapid research response workgroup with expertise in the pathogen of concern, research and development of investigational interventions, clinical trial design, and ethics and regulatory review, and including representatives from the affected communities, to

- Rapidly appraise and prioritize a limited set of vaccine and therapeutic products with the most promising preclinical and clinical data for clinical trials;

- Select a portfolio of trial designs that are best suited to the investigational agent(s) and the manifestation of the epidemic;

- The trial designs used should lead to interpretable safety and efficacy data in the most reliable and fastest way;

- Randomized trials are the preferable approach, and unless there are compelling reasons not to do so, every effort should be made to implement randomized trial designs; and

- Monitor and evaluate clinical trials conducted during an outbreak to enhance transparency and accountability.

There will be a need to connect the international coalition of stakeholders and its rapid research response workgroup with the other international response agencies during an epidemic and also with the leadership of national governments affected by an outbreak from the very onset of that outbreak in order to ensure that the affected population has a partnership position in the response. The responsibilities for the rapid research response workgroup should include making sure that resources for research are allocated efficiently and effectively, that the goals of the response and research activities are clear and agreed upon, and that community engagement and communication strategies are aligned. There should be thoughtful consideration given in the inter-epidemic period to developing an epidemic response stakeholder engagement strategy that includes a process for rapid mapping of key stakeholders at multiple levels (i.e., national to international and national to local leaders and opinion formers) at the onset of an epidemic. The goal is to encourage an open dialogue among all relevant stakeholders to achieve a better understanding of the nature of the crisis, each stakeholders’ interests, and resources available for addressing the epidemic, inclusive of the potential for research in the response.

BEING PREPARED: LAUNCHING CLINICAL TRIALS IN AN EPIDEMIC

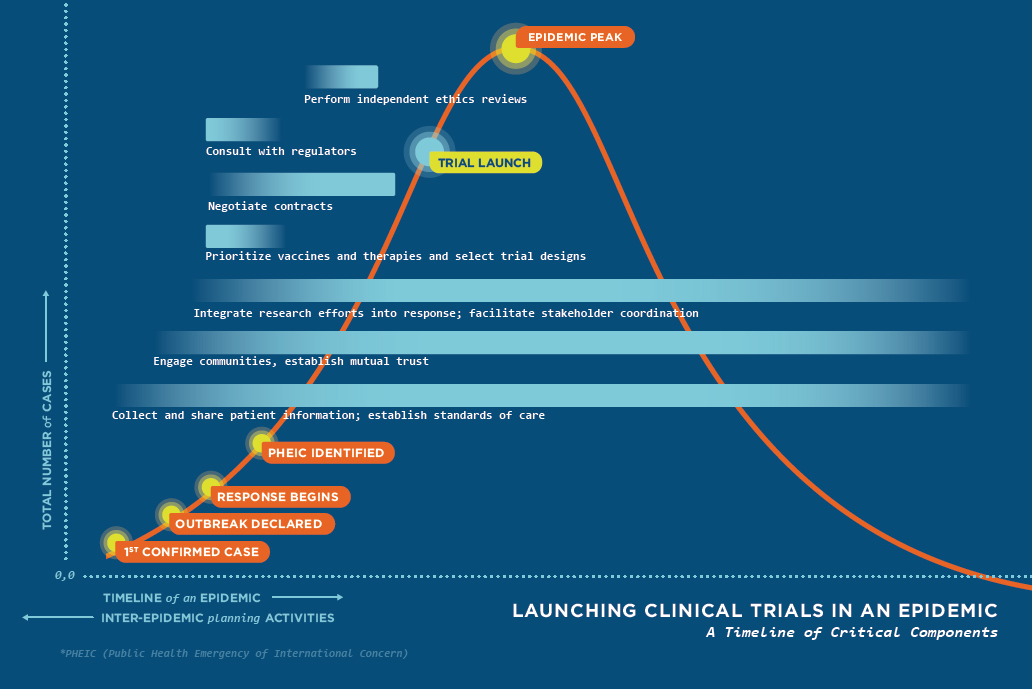

Through targeted exploration and analysis of scientific and ethical issues related to clinical trial design, conduct, and reporting during the 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, the committee learned key lessons that could be applied to future research conducted in settings where there is limited health care and research infrastructure. These lessons were then applied to developing the seven recommendations previously stated. Figure S-1 incorporates these recommendations into a visual representation of an idealized timeline of activities necessary to launch a clinical trial within the course of outbreak—represented as a standard epidemic curve.

The timeline is made up of seven key components that, if done in an efficient, coordinated, and timely manner, would enable trials to be launched before reaching the peak of the epidemic. However, attaining such a goal is unlikely without careful inter-epidemic planning and execution through a well-coordinated and collaborative effort from all involved parties. This includes national, international, and local representatives who each play a critical role in ensuring the global community is prepared to answer challenging questions through the conduct of research. It is through the development and implementation of sound clinical trials that best practices can be identified for improving clinical care for future populations both during and between public health emergencies.