7

Facilitating International Coordination and Collaboration

The clinical trials conducted during the 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic were done in an atmosphere and on a timeline immensely different from most clinical trials. The fact that trials were conducted at all is a demonstration of the ability of researchers, regulators, scientific and ethics review boards, and communities to work together around the clock when the need is pressing—but despite this success, it was not without avoidable conflict along the way. The trial teams should be praised for overcoming the complex and intertwined logistical obstacles encountered while trying to design and implement trials in West Africa in the midst of a rapidly spreading and highly dangerous contagious disease epidemic. The limited health care, public health, and health research infrastructure; the bureaucracy; fear, rumors, and lack of trust; and supply chain hurdles were just some of the barriers that had to be addressed and overcome. Despite the many challenges, much was learned about conducting clinical trials in this type of environment—lessons that may help future trials be more successful. The clinical studies also succeeded in contributing to the base of scientific knowledge about Ebola, including the importance of physiological support and the identification of sequelae that had not been clearly delineated in past outbreaks (Chiappelli et al., 2015).

Despite the successes, however, the overall scientific harvest of the trials was described as “thin” (Cohen and Enserink, 2015). As discussed in Chapter 3, none of the therapeutic trials ended with conclusive results concerning product efficacy, although the limited evidence from the ZMapp trials did trend toward a possible benefit (PREVAIL II Writing Group, 2016). And, as discussed in Chapter 4, there were two Ebola vaccine can-

didates studied that current data indicate may be safe and immunogenic, and one that is most likely protective, although further data on safety and efficacy are needed. However, given the resources, time, and effort that were put into these trials, they were not as successful as they could have been. The reasons for this are multiple and varied. First, when the initial serious discussions about pursuing clinical research were held by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other stakeholders in August 2014 they produced a long list of potential investigational agents, with various degrees of evidence to support their consideration. This led to trial teams independently selecting several different agents and ultimately competing for trial sites and patients rather than coordinating efforts and triage to focus on the most promising agents. Second, there was a lack of baseline information about the natural history of Ebola, clinical outcomes, and biomarkers that could inform patient care and clinical research. Third, several of the trials, as discussed in more detail in Chapters 3 and 4, had design issues limiting their chances of generating robust scientific data. Finally, many trials started too late in the course of the epidemic, launching as the outbreak was winding down. As a consequence even well-designed trials were unable to enroll a large enough participant population or to collect sufficient data to reach clear conclusions. One researcher reflecting on the experience stated that the “challenges . . . faced in the design, implementing, and reporting of the Ebola drug trials were not scientific, but political and administrative” (House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, 2016, p. 21). The committee concurs with the conclusion by the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee’s report Science in Emergencies: UK Lessons from Ebola: “The failure to conduct therapeutic trials earlier in the outbreak was a serious missed opportunity that will not only have cost lives in this epidemic but will impact our ability to respond to similar events in the future” (House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, 2016, p. 25).

The fact that clinical trials began a few months after the epidemic peaked was in part due to the nature of dealing with an unpredictable, unprecedented outbreak; the initial focus on ramping up response to meet immediate need rather than research; delays in recognizing how rapidly the outbreak was expanding (despite alerts to the international community on the part of Médecins Sans Frontières [MSF]); and, additionally, problems of coordinating research and response on the part of international organizations also contributed to the delay. When the outbreak was first identified as Ebola in March 2014, it was unknown how far it would spread or how long it would last—previous outbreaks had been brought under control in just a few months after infecting at most a few hundred people. The initial priority in 2014 was to provide patient care and prevent further spread through public health measures, and the idea to do clinical

trials for therapeutics or vaccines was not on the radar screen of the early responders and thus was overlooked.1 Despite the warning signs on the ground, with historical precedent in mind it was difficult to foresee how the epidemic would actually unfold and whether trials would be possible. Nevertheless, had certain mechanisms been in place before the epidemic struck, clinical trials could likely have begun before the epidemic began to wane. Starting trials earlier would have potentially allowed them to enroll a sufficient number of patients to permit the full analysis intended, thus increasing the likelihood that the trials would result in the identification of one or more safe and effective treatments or vaccines for Ebola or at least an incremental increase in the knowledge base that could lead to better products in the future.

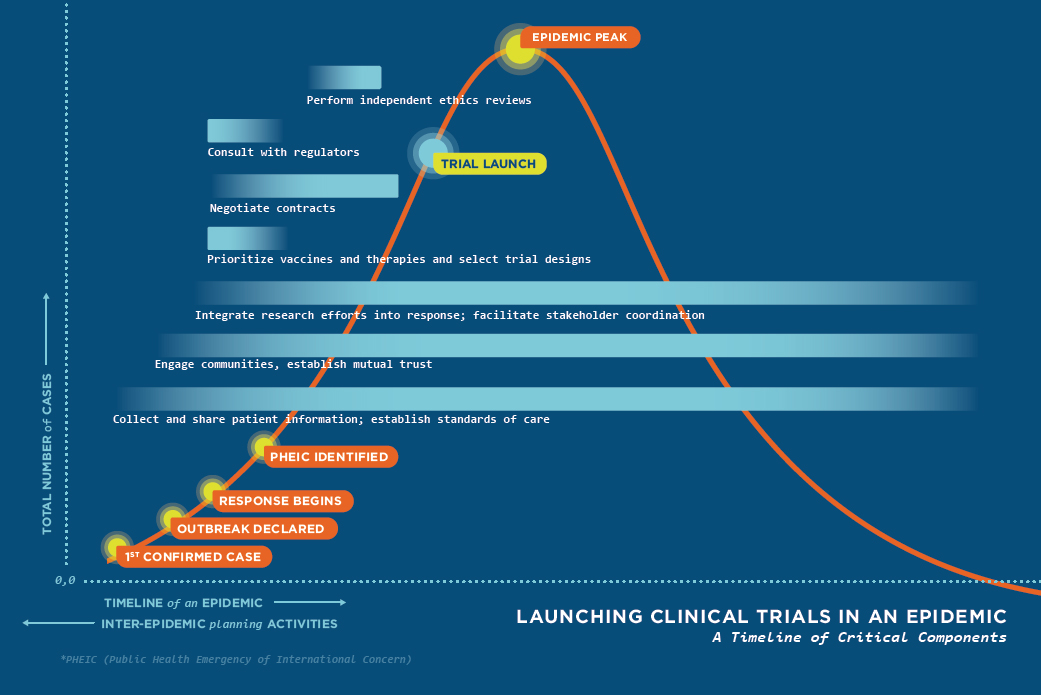

With these challenges in mind, the committee recognizes that several things will need to happen, often simultaneously, in order to execute clinical trials more efficiently in a future epidemic (see Figure 7-1). Substantial planning will be required in advance of the next epidemic in order to best position the international community to tackle these tasks, in partnership with affected countries. To enable a rapid prioritizing of investigational therapeutics and vaccines and the coordination of research efforts, the committee recommends a mechanism that will (1) foster collaborative investment in research and development (R&D) and (2) establish social trust and facilitate coordination among stakeholders.

INTER-EPIDEMIC PERIOD

The mobilization of a rapid and robust research response during the next epidemic will depend not just on what happens during the epidemic, but on what happens before and between epidemics—the inter-epidemic period. Building collaborative mechanisms, improving stakeholder relationships, and expanding investment into and planning of research during the inter-epidemic period will pay dividends when the next epidemic—of Ebola or another disease—strikes, regardless of where in the world it emerges.

___________________

1 To prevent research from being overlooked in the future the United Kingdom is supporting a promising model by allocating funding to support a public health rapid support team to be jointly run by Public Health England and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, with the University of Oxford and King’s College London as academic partners. It will have the ability to deploy within 48 hours to anywhere in the world that requests assistance. The team’s mission is to support national health systems to rapidly investigate and respond to disease outbreaks, and the team includes epidemiologists, microbiologists, experts in infectious disease control, social scientists, and experts in clinical research, thereby ensuring that research considerations including clinical research are included in response planning from the very beginning (PHE, 2016).

Research and Development

When the 2014–2015 epidemic began, there were a few Ebola-specific products in various stages of preclinical R&D, some of which had shown evidence of efficacy in animal models, including nonhuman primates. This preepidemic research was largely supported by a small set of funders, including civilian and military medical research and research funding agencies, albeit in line with the priority afforded to Ebola virus at the time—funding for Ebola R&D was limited. For example, a review of research funding in the United Kingdom from 1997 through 2013 reported zero Ebola research support out of £3.7 billion spent by public and philanthropic sources (Head et al., 2016). The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) did not report disease-specific funding until 2010, but during the period 2010–2013, some $540 million was allocated to Ebola and other hemorrhagic fever virus research (Kliff, 2014). Several Canadian government agencies invested a total of around $25 million in the decade before the outbreak to support seminal work on what became ZMapp and the VSV-EBOV vaccine, representing an exceptionally good return on these early investments (Grant, 2014). G-FINDER2 has recently provided, for the first time, an estimate of global research funding on Ebola during 2014 and of the proportional contribution of the U.S. government.

Virtually all reported funding for Ebola R&D in 2014 came from the top 12 funders ($164 million, 99.7 percent). Apart from aggregate industry and the Gates Foundation, all of these were public sector institutions from North America and Europe. Three of the top five were U.S. government agencies: the NIH ($64 million, 39 percent), the U.S. HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] ($26 million, 16 percent), and the U.S. Department of Defense: Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA, $11 million, 6.6 percent). Collectively, these three U.S. organizations provided 78 percent of all non-industry investment in Ebola R&D. (Moran et al., 2015, p. 31)

If not for these initial investments in research and early preclinical development, it is very unlikely that any products would have been any-

___________________

2 G-FINDER is a uniquely informative data source, providing policy makers, funders, researchers, and industry with objective, previously unavailable information on the state of investment, trends, and patterns

- in 35 neglected diseases;

- across 142 product areas for these diseases including drugs, vaccines, diagnostics, microbicides and vector control products; and

- in platform technologies (e.g., adjuvants, delivery technologies, diagnostic platforms).

The data include all types of product-related R&D, including basic research, discovery and preclinical, clinical development, Phase IV and pharmacovigilance studies, and baseline epidemiological studies (Policy Cures, 2017).

where near ready for clinical trials when the outbreak occurred. It should also be noted that in the most recent G-FINDER survey results released February 2017, with the notable exception of Ebola R&D, spending on neglected disease is at its lowest level since 2007 (Ross, 2017)—a dismal prospect if the global community hopes to be prepared in the event of a future outbreak.

The severity and rapid escalation of transmission of Ebola in West Africa during 2014 motivated the initiation of clinical trials, as the situation was so desperate and the epidemic would be the only opportunity to evaluate efficacy in humans. The usual process of drug development from bench to bedside3 is estimated to, on average, take at least 10 years and cost $2.6 billion, with fewer than 12 percent of the products under development likely to be eventually licensed (DiMasi et al., 2016). Given the length of the typical Ebola outbreak and the length of time it takes to conduct drug discovery and assess safety and efficacy, the odds that a new compound could be discovered and fully evaluated during an outbreak are vanishingly small. Even with preliminary evidence, a drug in development with limited or no human safety and efficacy data would be very unlikely to gain regulatory approval on the basis of data generated during the outbreak and in time to be deployed during the same outbreak. Unless the data were especially promising, the likely best case scenario for a new drug or vaccine would be provisional approval for use in clinical trials or possibly for expanded access to high-risk groups, but not approval for the general population. Even with a limited expanded access approval, manufacturers would have to ramp up rapidly to make the product available before the epidemic waned.

The R&D of products—including therapeutics, vaccines, assays, and diagnostic tests—during the inter-epidemic period is the most likely pathway to ensure that promising candidates are available to study during an epidemic. Conducting Phase 1 safety trials during the inter-epidemic period (either in the country in which the product originated or in countries with populations at risk of the disease, or possibly both) could considerably facilitate the approval process and more rapid implementation of efficacy trials at the occurrence of an outbreak. The decision of whether to conduct Phase 1 trials in populations who have a near-zero risk of infection (i.e., in the country in which the product originated) will depend on a number of factors, including the specifics of the pathogen and of the investigational agent. For example, if the investigational product is suspected to have high toxicity or a vaccine is a live-attenuated vaccine, it may not be reasonable to perform this research in healthy participants in countries with a near-

___________________

3 The term bench to bedside is used to describe the process by which the results of research done in the laboratory are directly used to develop new ways to treat patients (NCI, 2017).

zero risk of infection. However, there are advantages to conducting Phase 1 studies in high-income settings; for example, given the greater resources and better infrastructure available, it may be easier to track and detect adverse events. During the Ebola epidemic it proved to be possible to recruit volunteers in high-income settings. A major advantage of conducting initial Phase 1 research in the country of product origin is that it may alleviate some of the distrust of the affected populations, diminish the concerns that their population is being used as “guinea pigs,” and speed the approval and implementation of clinical trials during the outbreak. To conduct these types of activities during the inter-epidemic period will depend first on the existence of a vigorous R&D agenda; second, on a system for ongoing surveillance of known and potentially new and emerging pathogens; third, on a continuous process to assess priorities for research support, perhaps including incentives for private-sector R&D; and fourth, on sufficient vision and commitment from leaders inside and outside of government and science. The committee agrees with the assessment of the Ebola Vaccine Team B4—and for therapeutics as well—that the “need for Ebola vaccines (including multivalent filovirus vaccines) remains an urgent public health priority. Renewed and continued global leadership is required to complete the task of licensing and delivering safe, effective, and durable multivalent Ebola vaccines for prophylactic and reactive use. Achieving this outcome is critical not only for Ebola preparedness, but also for proof of concept that vaccines to protect against other neglected or emerging infectious diseases can be successfully developed in the future” (Ebola Vaccine Team B, 2017).

The WHO and its member states have recognized the importance of R&D in preparing for and responding to outbreaks. In October 2015, as part of the Oslo consultation, Financing of R&D Preparedness and Response to Epidemic Emergencies, participants proposed that stakeholders should aim to do the following (WHO, 2015b):

- Increase their overall investment in R&D for emergency preparedness.

- Align their different R&D efforts to address the global priorities identified in the WHO R&D blueprint under preparation as well as other ongoing processes.

___________________

4 The Wellcome Trust and the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota established the Ebola Vaccine Team B in November 2014 to support international efforts to stop the rapid spread of Ebola virus disease in West Africa. The group’s purpose is to provide a complementary and creative review of all major aspects of developing and delivering effective and safe Ebola vaccines, including funding, research, development, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness determination, licensure, manufacturing, and vaccination strategies. The Wellcome Trust–CIDRAP Ebola Vaccine Team B includes 25 international subject-matter experts involved in one or more areas of vaccine work (Ebola Vaccine Team B, 2017).

- Ensure efficient use of existing funding mechanisms by avoiding duplication of efforts.

The failure to support R&D for emerging infectious diseases can have severe consequences, as participants at the Oslo consultation discussed: “The lack of vaccines, drugs, and diagnostic tests for infectious diseases with epidemic or pandemic potential is a severe threat to global public health. [Ebola] in West Africa has taken a devastating human toll . . . [and] has also had a significant direct economic impact and continues to weaken the economies of the three hardest-hit countries with a projected $2.2 billion in lost GDP [gross domestic product] for 2015. Experiences with previous disease outbreaks (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS]) paint similar grim pictures” (WHO, 2015b). The idea that the international community should work together to address the gaps in R&D for priority pathogens that place populations at risk of epidemics seems obvious, particularly in hindsight. However, the historical problem remains: how to keep the focus of global leadership on the threat of future pandemic outbreaks and on supporting the vision of innovators in R&D, when there are so many different threats, even just for global health.

Operational Considerations

Conducting clinical trials requires addressing a litany of bureaucratic, legal, and ethical issues in addition to the scientific considerations. While Ebola trials were launched during the epidemic in record time, the lack of preplanning for research, and the sole focus on ramping up the critical humanitarian response in the early months of the international response resulted in the first patients not being enrolled in trials until the epidemic was already waning. At the time that the epidemic was still rapidly growing and spreading, researchers had to complete operational tasks such as establishing legal agreements, arranging for specimen analysis, and solving logistical issues. These challenges were compounded by the scarcity of resources and minimal research experience available in the affected countries, which at times led to perceptions of imbalances and mistrust between foreign sponsors and host countries. The imbalance in experience negotiating clinical trial contracts led to the perception, if not the reality, that foreign sponsors had much greater influence over the contracts than the in-country negotiators.5 Additionally, because the lack of highly technical laboratory capacity present in country led to some of the clinical specimens

___________________

5 Testimony of several workshop participants. Public Workshop of the Committee on Clinical Trials During the 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak, August 15–17, 2016, Monrovia, Liberia.

being exported for analysis (Schopper et al., 2016), the signing of material transfer agreements between host countries and researchers had “the potential of creating a lot of suspicion and mistrust if not well handled and documented” (Folayan et al., 2015, p. 2). Further, the fact that the Ebola-affected countries had relatively few and relatively inexperienced lawyers available to help execute material transfer agreements to get samples out of country and get investigational products into the country reportedly slowed response time on the part of the West African authorities and, consequently, resulted in additional delays in getting trials going. To address this common situation in low- and middle-income countries, the Council on Health Research for Development developed a Fair Research Contracting Initiative as a model program for low- and middle-income countries to adopt and enhance local competence (Marais et al., 2013).

These logistical and operational tasks “need to be done in days rather than weeks or months,” says a researcher involved in the clinical trials conducted during the Ebola outbreak. She added that in order to address this issue, “research has to be embedded in the immediate response to an outbreak and not come as an afterthought” (Kelland, 2015). The committee strongly endorses this perspective. If emergency and epidemic response plans include ways to address these operational and logistical challenges, clinical researchers can overcome these hurdles more quickly and begin to evaluate potential agents to stop the outbreak more expeditiously than before, particularly if much of the general clinical trial planning work is done during the inter-epidemic period.

Conclusion 7-1 Research and development is a complex and lengthy process that cannot be compressed into the course of a rapidly progressing outbreak. Prior investment in R&D is required during the inter-epidemic period for priority known pathogens and for the development of new approaches to speed the discovery and development of investigational products for emerging but still unknown or unrecognized pathogens.

Conclusion 7-2 Clinical trials can be more rapidly planned, approved, and implemented during an outbreak if (1) promising products have already been studied through Phase 1 or Phase 2 safety trials (when possible), particularly if there are preliminary efficacy data in a relevant animal model; and (2) if emergency response planning includes clinical research considerations and clinical researchers in the discussions from the beginning.

International Coordination

As discussed in Chapters 2–4 of this report, fortunately, there were a few Ebola-specific therapeutic and vaccine candidates in the R&D pipeline available for clinical research at the beginning of the outbreak. However, there was no a priori agreed-upon approach to prioritizing these candidates for clinical trials. The therapeutic category included not only untested Ebola-specific products, but also already-licensed drugs that could potentially be repurposed for Ebola and a variety of other proposed agents with little, if any, evidence or theory for their selection. There were also a few vaccine candidates in the pipeline at the time, with limited safety and efficacy information. With the long list of investigational agents competing for attention, the WHO-convened meetings aimed at harmonizing efforts were frequently tense and contentious as stakeholders not only disagreed on how to prioritize what to study, but also disagreed on how to design trials and debated issues such as randomization and the use of control groups. No infrastructure for the conduct of the trials was in place in the affected countries before the outbreak, nor was there a plan to coordinate across multiple studies to ensure that the available resources were used optimally to generate as much data as quickly as possible during the outbreak. The lack of coordination fostered competition among the trial teams over trial locations and trial participants, particularly as the epidemic waned and the number of new patients began to drop (Kupferschmidt, 2015). In its account of the Ebola outbreak, the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (2016) reported the conclusions of Professor Trudie Lang of the University of Oxford about this lack of coordination: “[H]aving ‘five different groups testing five different things’ was ‘not an overly sensible approach’ since it resulted in an ‘absurd situation’ whereby a disorganised and ‘unorchestrated throng of researchers’ were each ‘negotiating for access to patients’ on the ground. [Professor Lang] stressed that ‘better co-ordination’ was needed in the future, combined with a more obvious prioritisation of research studies” (House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, 2016). Gelinas et al. (2017) recently explored the consequences of competition among similar clinical trials for participants, using as an example a hypothetical cancer center with multiple trials intended for the same patient population. Their conclusion was that “such a competition is a predictor of low study accrual, with increased competition tied to increased recruitment shortfalls . . . [and a] policy that prioritises some trials for recruitment ahead of others is ethically permissible and indeed prima facie preferable to alternative means of addressing recruitment competition” (Gelinas et al., 2017, p. 1).

In the future, in order to better gain stakeholder buy-in and increased cooperation in a coordinated research plan, it seems advisable to engage

experienced meeting facilitators at stakeholder meetings, both in the inter-epidemic period and particularly at the start of an outbreak, to introduce and facilitate neutral and productive discussions among stakeholders and determine an agreed-upon process to adopt. Future meetings would also benefit from real-time stakeholder feedback to ensure the processes and goals are acceptable to all. According to former NIH ombudsman, Howard Gadlin, “ongoing assessment of process factors in teams is essential at the very beginning, at the midpoint, and at the end. . . . It’s important for any group that’s meeting to put aside time, even if it’s just 5 minutes at the end of the meeting, to talk about how we did. What we handled well, what did we not handle well, what should we do differently in the future, paying attention to the emergence of group norms that may be somewhat counter-productive.”6

It would be valuable and advantageous for the principal stakeholders, during the inter-epidemic period, to engage in early planning that is focused on the development of a list of priority pathogens to target for R&D, the creation of generic protocols, to establish memoranda of understanding, and to discuss material transfer agreements and other administrative details that would suddenly become high priority during an emerging infectious disease outbreak such as a central data repository. For example, in the case of protocols, the coalition of stakeholders discussed below would seek consensus about specific trial design issues for different priority pathogens, such as the population to be studied, the trial’s primary endpoint including the potential role of surrogate measures, the use of individual versus cluster randomization, the feasibility of blinding the randomization, and approaches to improve efficiency by simultaneously evaluating complementary interventions such as through the use of factorial designs. These templates can be adapted to the specific circumstances of a particular outbreak and will speed up the planning, coordination, and approval process. This could become a part of an emergency outbreak document database (discussed in Chapter 5), perhaps posted and maintained by the WHO, and freely and openly available to everybody with interest. These tasks are time consuming, but they are expected necessities in launching clinical trials. Given the litany of bureaucratic tasks required for trials, creating an interactive social setting to develop these documents and reach agreements in advance of the next epidemic could result in a global community whose members are more comfortable with one another and who are better able and more willing to prioritize and collaborate in order to more quickly launch trials when necessary. These issues should be enlightened by the participation of experts from clinical and statistical science areas, from

___________________

6 Testimony of Howard Gadlin, retired NIH ombudsman. Public meeting of the Committee on Clinical Trials During the 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak, Washington, DC, June 15, 2016.

academia, government, and industry, from ethics and regulatory bodies, from humanitarian nongovernmental organizations, and from foundations and at risk local communities.

Another outbreak similar to the Ebola epidemic will surely occur in the future. It is uncertain which pathogen will be the cause of the outbreak or in which geographical location the outbreak will occur, but it will happen. To enable research to begin much more quickly in this situation, it is essential to consider how to bring the various stakeholders together and to do it now. To this end, the committee recommends that an international coalition of stakeholders (ICS) be convened in order to improve inter-epidemic planning and coordination. Events on a global scale generally require a global solution, which in turn requires international coordination and cooperation. There are no events for which this is more applicable than emerging infectious diseases outbreaks, for even when initially localized within a country’s borders such outbreaks can quickly become global. Within our recent memory, outbreaks due to severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), Ebola, and now Zika have amply demonstrated the truth of this view. What remains is to determine how to most effectively make this process real. That is why the committee sought to consider existing models or organizations that could lead this effort, rather than recommending an entirely new entity be formed. The below discussion considers the WHO, the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), a new multistakeholder organization created to “stimulate, finance, and coordinate the development of vaccines against epidemic infectious diseases, especially in cases in which market incentives alone are insufficient” (Røttingen et al., 2017).

Conclusion 7-3 It is unrealistic to assume that all of the necessary planning and coordination activities for efficiently conducting clinical trials during an epidemic and avoiding unnecessary delays can take place after an outbreak begins and while it is ongoing. Activities that build relationships and address foreseeable problems in implementing a research program—such as determining how to evaluate competing trial proposals, deciding what should be included in clinical trial contracts, and educating national researchers and review boards in study conduct—must begin in the inter-epidemic period.

Conclusion 7-4 To increase the likelihood of success there is a need for an international coordination and collaboration mechanism to guide investment decisions, encourage broad participation of the global R&D community, and steward the process from early discovery to the registration of safe and effective products.

Recommendation 7a

Coordinate international efforts in research and development for infectious disease pathogens—Inter-epidemic

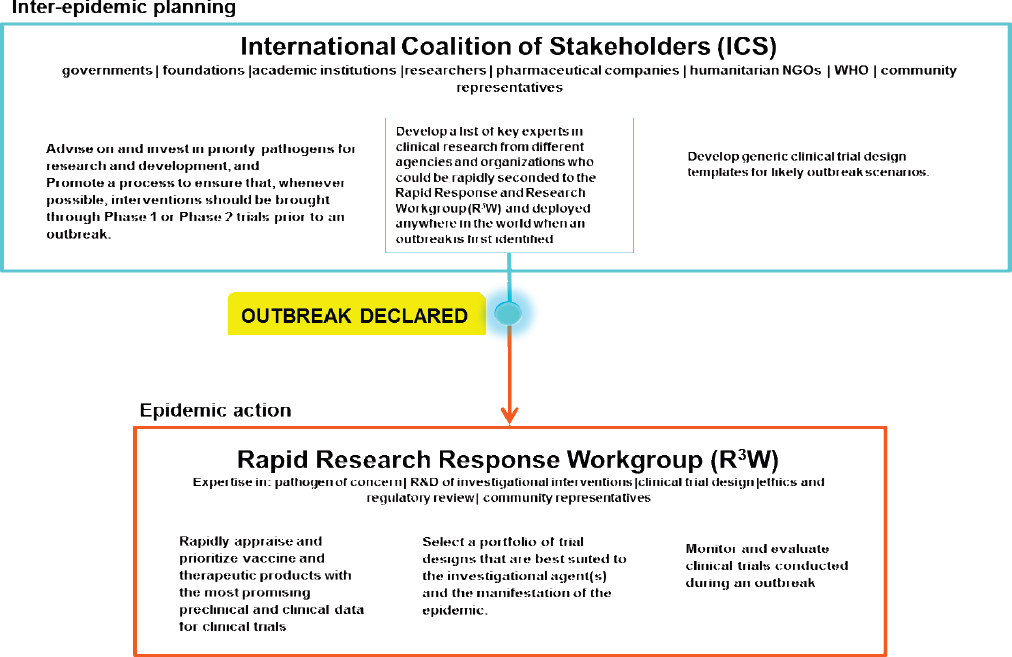

An international coalition of stakeholders with representation from governments, foundations, academic institutions and researchers, pharmaceutical companies, humanitarian organizations, and the World Health Organization (such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) should work on the following planning activities to better prepare for and improve the execution of clinical trials conducted during infectious disease events:

- Advise on and invest in priority pathogens to target for research and development, and promote a process to ensure that, whenever possible, interventions should be brought through Phase 1 or Phase 2 trials prior to an outbreak.

- Develop generic clinical trial design templates for likely outbreak scenarios. The reasoning and rationale behind the designs and the situations in which each would be best utilized should be discussed with representatives of ethics review boards, major humanitarian organizations, and at-risk local communities to promote buy-in from stakeholders in advance of an outbreak.

- Develop a list of key experts in clinical research from different agencies and organizations who could be rapidly seconded to the coalition of stakeholders and deployed anywhere in the world when an outbreak is first identified.

DURING AN EPIDEMIC

While inter-epidemic planning and coordination may set stakeholders up for success, it is when an epidemic strikes that the rubber hits the road. Regardless of how much planning has been done before the epidemic, the steps that are taken in the early days of the outbreak set the course for the response and the potential for robust research. An epidemic presents the best—and sometimes only—opportunity to study a pathogen, the natural course of a disease, and the efficacy of investigatory treatments or vaccines. Care must be taken to conduct research efficiently and effectively and to use research designs that are most likely to produce reliable results, while considering feasibility and acceptability in the context of the epidemic. Each aspect of conducting research during an epidemic—following a research agenda, prioritizing agents for study, choosing trial designs, engaging with the community—can be best accomplished through a coordinated international effort. This committee recommends that upon the emergence of an epidemic, the ICS designate a rapid research response workgroup (R3W) to coordinate the research response. This working group would appraise and

prioritize the most promising agents to study, select the trial designs that are best suited to the context of the epidemic, and monitor and evaluate the clinical trials that are conducted during the outbreak. The workgroup should include stakeholders with expertise in areas such as the pathogen of concern, R&D of investigational interventions, clinical trial design, and ethics and regulatory review, and include representatives from the affected communities (see the following section for more details).

Recommendation 7b

Establish and implement a cooperative international clinical research agenda—Epidemic

In the event of an emerging epidemic the international coalition of stakeholders in Recommendation 7a should designate an independent multistakeholder rapid research response workgroup with expertise in the pathogen of concern, research and development of investigational interventions, clinical trial design, and ethics and regulatory review, and including representatives from the affected communities, to

- Rapidly appraise and prioritize a limited set of vaccine and therapeutic products with the most promising preclinical and clinical data for clinical trials.

-

Select a portfolio of trial designs that are best suited to the investigational agent(s) and the manifestation of the epidemic:

- The trial designs used should lead to interpretable safety and efficacy data in the most reliable and fastest way.

- Randomized trials are the preferable approach, and unless there are compelling reasons not to do so, every effort should be made to implement randomized trial designs.

- Monitor and evaluate clinical trials conducted during an outbreak to enhance transparency and accountability.

Stakeholder Coalition

In order to develop the international collaborative mechanisms described in Recommendations 7a and 7b (see Figure 7-2 for a diagram of Recommendations 7a and 7b), an ICS for product R&D and implementation of clinical research, including prioritization of products to be evaluated in clinical trials, will need to be identified. First, in order for it to be available to serve at the outset of an epidemic, the ICS must be organized in the inter-epidemic period and include all relevant stakeholders. This list is long and should include, for example, the WHO, research organizations in regions of the world where outbreaks are likely to occur, regional scientific groups and academic centers, large research organizations from developed countries with experience in global health and emerging infectious diseases

NOTE: NGO = nongovernmental organization; R&D = research and development; WHO = World Health Organization.

research, major research funders (e.g., NIH, Inserm, Wellcome Trust), pharmaceutical companies, regional research collaborations (e.g., Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness [GLOPID-R], REACTing: REsearch and ACTion targeting emerging infectious diseases), as well as pan-African, Asian, and South American public health and research organizations. Through its interactions with WHO and its focus on the capacity for response, the ICS would involve international organizations providing ongoing care in locations where outbreaks are likely to happen (e.g., MSF, International Medical Corps, GOAL Global), as well as ethicists, and regulators.7 The skillsets required are broad, but the number of people involved needs to be small enough for the ICS to work efficiently and be able to reach thoughtful consensus, perhaps by working through smaller subgroups or committees. Second, to be functional and efficient there is need for an autonomous expert working group, free of significant conflicts of interest, which has the mandate to make rapid decisions to shape and guide the clinical research agenda and prioritize which trials can go forward. This is the R3W proposed in Recommendation 7b.

The ICS could play a very important strategic role in coordinating the interests of the research community and its potential to generate valuable new knowledge during an outbreak. It should work in tandem with the WHO, which has responsibilities for oversight and improvement of the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR 2005) core capacities, and coordinates emergency response partnerships (Gostin and Katz, 2016). For example, as a part of its functions the ICS would need the input of R&D experts to help guide and focus the R&D agenda during the inter-epidemic period. It would then be ready to participate with WHO in the global emergency response planning from the very beginning of an outbreak and the declaration of a public health emergency of international concern. The ICS would also be in a preferred position to identify and delegate a smaller, highly expert group to form the R3W, together with representatives from affected countries, to prioritize the products to go into clinical trials during the outbreak and coordinate and monitor their implementation. The R3W could also provide support to the health research system in those countries as proposals are developed as a collaboration of international and national research institutions together with pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, and are submitted for national scientific and ethical review, and, if accepted, implemented as soon as possible. Its

___________________

7 Although regulators’ role is not to choose the agents that should be investigated, they have a wealth of expertise in research design to contribute, and they may inform and broaden discussion and debate within the scientific community. In addition, regulators may be able to work with researchers in offering more flexible regulatory pathways and enabling rapid review during the time-sensitive part of an epidemic.

hallmarks would be that it has R&D expertise, it is connected to but independent of both the coalition and the humanitarian emergency response team that convenes to guide the mobilization of global resources, and it is able to help integrate the clinical research opportunities into the planning process from the beginning. It would require broad-based connections to the international community, and the endorsement of the ICS, the WHO, and other relevant UN agencies, regulatory agencies in the countries of origin of products and in the countries experiencing the outbreak, and the research and manufacturing sectors. There would need to be explicit agreement forged during the inter-epidemic period that the decisions of the R3W on priorities for moving a product into clinical research would be binding on all of the stakeholders.

The committee examined three possible entities that could take the lead in establishing such mechanisms for research governance, including the ICS and the R3W: (1) the WHO, (2) the Global Health Security Agenda, and (3) the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations.

World Health Organization

R&D for emerging infectious diseases is a vast challenge, and it requires depth in basic, translational, and clinical research expertise; focus; and a big budget. The WHO has many tasks to address, has limited technical R&D expertise among its staff, and is dependent on donor funds for its research activities. The various shortcomings of the WHO’s performance over the 5 months from the time Ebola was confirmed in March 2014 until the WHO declared the public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on August 8, 2014, have subsequently been acknowledged by the organization (WHO, 2015c). This triggered a deep internal review, resulting in a plan to substantially improve the organization’s future performance “to ensure that WHO maintains appropriate levels of organizational readiness, supports country-level capacity building and preparedness, deploys efficiently and effectively to respond to outbreaks and emergencies at national and subnational levels, and engages effectively with partners and stakeholders throughout” (WHO, 2015a, p. 1). The document discusses six major items and issues for WHO to adopt or address in order to improve performance:

- A unified platform for readiness and response to outbreaks and emergencies.

- A global health emergency workforce.

- Country-level IHR 2005 core capacities.

- The function, transparency, effectiveness, and efficiency of the IHR 2005.

- A framework for R&D preparedness and enabling R&D during outbreaks or emergencies.

- International financing.

This is an enormous responsibility which will require substantial staff time and expertise to carry out, established and well-used communication mechanisms up and down the chain between the country offices and WHO Geneva, and process checks to ensure that the information flow is working and that there are enough well-trained staff available to carry out these responsibilities effectively and efficiently. WHO’s analysis recognizes that “the world, including WHO, is ill-prepared for a large and sustained disease outbreak. . . . We have taken note of the constructive criticisms of WHO’s performance and the lessons learned to ensure that WHO plays its rightful place in disease outbreaks, humanitarian emergencies and in global health security” (WHO, 2015c). After this reflection, WHO identified five key steps it needed to take in order to improve its performance in the future: first, take disease threats seriously; second, remain vigilant; third, help to reestablish the devastated services, systems, and infrastructure in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone; fourth, be transparent in reporting; and fifth, invest in research and development for the neglected diseases. It is worth considering whether the WHO ought to be the responsible party for all of the above tasks.

Without doubt, the WHO is an essential part of the international response to outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases. The effectiveness of the international response depends on how well the WHO focuses its attention for action and how well it partners with—and, when appropriate, cedes responsibility to—other organizations in order to harness their particular strengths, experience, and resources. For the WHO to cede responsibility for aspects of the broad international response required will be difficult unless the boundaries of responsibility among the various partners are clearly delineated in advance and effective mechanisms for communication and data sharing among the partners are established before an outbreak. In the committee’s view, the WHO is not the optimal organization to shepherd the research and development of drugs and vaccines for emerging infectious diseases because it lacks the depth of expertise and the resources needed to support and undertake clinical research. The WHO must be at the table, but not as the chair, as it has enough to do already and needs to focus on doing that right as well. In this determination the committee finds itself in agreement with the Ebola Vaccine Team B analysis that “Despite the WHO’s leadership role, it is not in a position to manage and fund all of the complexities associated with bringing Ebola vaccines to market. While the WHO can generate guidance documents, lead collaborations, and convene stakeholders through workshops and other platforms,

the organization lacks the authority and extensive resources necessary to surmount some of the biggest remaining challenges associated with Ebola vaccine development” (Ebola Vaccine Team B, 2017). In recognition of these various concerns, and in a very positive step forward, the WHO has recently refined its role in the global R&D arena for emerging infectious diseases. “To fulfil its mandate, WHO has a core responsibility in the area of research and coordination of research. WHO will use its convening capacity to fulfil this responsibility. Although WHO is not a funding agency nor in general a major implementer of research activities, it has a global mandate to set evidence-based priorities and standards for research, ensuring that all voices are heard and avoiding conflicts of interests. Success of the R&D Blueprint will certainly depend on the concerted efforts of all stakeholders” (Kieny et al., 2016).

Global Health Security Agenda

Another model the committee considered is the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), a recent initiative to connect relevant parts of the U.S. government8 with partners around the world on emerging infectious disease threats. The specific goal envisioned for GHSA is

to advance a world safe and secure from infectious disease threats, to bring together nations from all over the world to make new, concrete commitments, and to elevate global health security as a national leaders-level priority . . . [and promote a] multilateral and multi-sectoral approach to strengthen both the global capacity and nations’ capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious diseases threats whether naturally occurring, deliberate, or accidental—capacity that once established would mitigate the devastating effects of Ebola, MERS, other highly pathogenic infectious diseases, and bioterrorism events.” (GHSA, 2016b)

GHSA was launched in February 2014 (see Box 7-1, Global Health Security Agenda for GHSA’s major commitments at the time of its launch) just as the Ebola outbreak was beginning to escalate but was still unrecognized. It was created as an expansion of the 2009 USAID Emerging Pandemic Threats program, which was designed to

aggressively pre-empt or combat . . . diseases that could spark future pandemics. . . . [It is] composed of four complementary projects operating in 20 countries—PREDICT, PREVENT, IDENTIFY, and RESPOND—with

___________________

8 Including HHS, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. Department of Defense (which includes the medical research organizations of the U.S. military), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (which includes the agricultural research enterprise for animal diseases).

technical assistance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Emerging Pandemic Threats global program draws on expertise from across the animal and human health sectors to build regional, national, and local ‘One Health’ capacities for early disease detection, laboratory-based disease diagnosis, rapid response and containment, and risk reduction. (USAID, 2016)

While GHSA is relevant to the goal of responding to emerging infectious diseases threats through international cooperation and collaborations, it is not an R&D program for therapeutics and vaccines. The principal basic and translational health research component of the U.S. government, NIH, and other similar research focused institutions internationally, are not significant partners in GHSA. Even without R&D, the rest of the GHSA

is complex enough to fully occupy the attention of the involved agencies. GHSA currently lists 55 partner nations, including Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, as well as a number of international organizations and nongovernmental stakeholders such as the WHO, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health, Interpol, the Economic Community of West African States, the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, and the European Union (GHSA, 2014, 2016a). It now operates a set of 11 agreed-upon action packages which range across the themes of prevent, detect, and respond to emerging pandemic threats in order to “translate political support into action and to guide countries toward achieving the GHSA targets . . . by building capacity at a national, regional, and/or global level” (GHSA, 2014). Unfortunately, there is no indication on the GHSA website that any of the three West African nations affected by Ebola are contributing countries under any of the 11 action packages. The committee looks forward to GHSA addressing this very important agenda, but it does not consider GHSA the right structure to entrust with the R&D and clinical research agenda; furthermore, GHSA is driven by one country, and its priorities and commitments may change with changes in national leadership.

Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

There are other new concepts for international coordination and cooperation more specifically targeted to R&D, including vital clinical research, for emerging epidemic diseases. A particularly interesting new entity is the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which was formally launched in January 2017 (Brende et al., 2017; CEPI, 2017). CEPI is being driven by five founding partners—the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the government of India, the Wellcome Trust, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the World Economic Forum—with an expanding list of coalition partners (CEPI, 2016b). For example, it has also received large financial contributions from Japan and Germany (Brende et al., 2017). It is rapidly becoming operational under the leadership of an experienced interim chief executive officer, John-Arne Røttingen, previously the executive director of infection control and environmental health at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and a professor of health policy at the Department of Health Management and Health Economics, Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo, and chaired by Professor K. VijayRaghavan, Secretary of the Indian Department of Biotechnology. Because of the resources of the partners and the focus of its mission, CEPI has the potential for significant investments that can be used to dramatically speed up the development of vaccines for emerging infectious diseases, with the goal of raising $1 billion for its first 5 years of operation. According to CEPI,

The R&D response to the Ebola epidemic in West Africa was both a success and a failure. Never before have industry, government agencies, academia and NGOs [nongovernmental organizations] collaborated so effectively to plan and conduct more than a dozen clinical vaccine trials in less than a year. But it also showed that the R&D system is not prepared for these threats: we had not done the right research before the epidemic, causing needless delay and loss of life. CEPI will build on the spirit of working together that was ignited by Ebola to create a new R&D system for epidemics that several international panels have demanded. This partnership will give us the new vaccines we need for a safer world. (CEPI, 2016b)

A recent editorial in Nature stated, “At a time when short-termism and shortsightedness are rife, and political rhetoric often prevails over action, CEPI’s founders are offering vision and foresight—it’s an insurance policy that more governments, including the United States, would be well advised to back” (Nature, 2017). CEPI’s approach to vaccine development is innovative, designed as

an end-to-end approach—we won’t take on discovery research or vaccine delivery, but we will work through all the steps in between. We will stay abreast of new discoveries and technologies, and we’ll work with other organizations to make sure any vaccines that are developed reach those who need them. Equitable access will be a founding principle of CEPI, so that vaccines developed with its support are available to all who need them—price should not be a barrier—and they are available to populations with the most need. We expect that many of the vaccines CEPI helps to develop will not be profit-making, and we will work with our partners to ensure that the risks, costs and benefits of development are shared proportionately. (CEPI, 2016a)

CEPI’s intent is to build on the WHO R&D Blueprint for Action to Prevent Epidemics, which is a good starting point to address the need for improved R&D preparedness for diseases of epidemic potential and for the ability to conduct responsive R&D in emergencies, to prioritize the pathogens of greatest interest and identify the R&D priorities, and to explore funding models for R&D preparedness and response (WHO, 2016). With the global recognition and significant financial and scientific resources of the founding partners, CEPI is already taking steps to lead international coordination and cooperation in vaccine development for emerging infectious diseases. For example, it organized a scientific conference which took place in February 2017 in collaboration with Inserm to assess progress in vaccine R&D for the WHO priority pathogens and other unknown pathogens with epidemic potential and to update the goals for vaccine R&D, manufacturing, and clinical development (CEPI, 2016c; Røttingen, 2016).

CEPI has the power of the founding coalition and its resources to function as an independent scientifically driven clearinghouse for vaccines, and while the WHO is a CEPI partner, it is the rest of the coalition that brings the scientific and R&D strengths and resources.

Major prospective co-funders include NIH and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in HHS; the European Community and the European Union’s Innovative Medicines Initiative and the European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership; public- and private-sector implementers and innovators, such as multinational corporations, research institutes, and product development partnerships; regulators and normative bodies (e.g., the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Authority, the WHO PreQualification Programme, and the African Vaccine Regulatory Forum); national academies of medicine or science; and procurement and distribution partners such as the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization. The committee recognizes that CEPI is a model that is still early in its development and is focused on vaccine development, but it also recognizes that if CEPI is successful in the vaccine arena, it could in the future tackle the need to coordinate and cooperate on the development of new safe and effective therapeutics. It has the “right DNA for the job,” and we are hopeful that it will quickly evolve and be willing to take on the broader role envisioned by the committee.

EMBEDDING RESEARCH INTO RESPONSE

There will be a need to connect the proposed ICS and R3W with other international response agencies during an epidemic and with the leadership of national governments affected by an outbreak from its very onset in order to ensure that the affected population has a partnership position in the response. Together, the response and research agencies and organizations can share the responsibility and allocate resources efficiently and effectively so that the goals of the response and research activities are clear and agreed upon, and that community engagement and communication strategies are aligned. One way to get research at the table from the beginning would be to include representation from the proposed ICS on the WHO IHR Emergency Committee constituted under IHR 2005 which is responsible for advising the WHO director-general whether an outbreak should be identified as a PHEIC; it is this that triggers the international response to contain the outbreak and help to care for infected individuals (WHO, 2017).

Because the tasks and burdens at the beginning of an outbreak are complex and involve multiple stakeholders, there should be thoughtful consideration given in the inter-epidemic period to developing an epidemic

response stakeholder engagement strategy that includes a process for rapid mapping of key stakeholders at multiple levels (i.e., national to international, and national to local leaders and opinion formers) at the onset of an epidemic. The goal is to encourage an open dialogue among all relevant stakeholders to achieve a better understanding of the nature of the crisis, each stakeholders’ interests, and resources available for addressing the epidemic, inclusive of the potential for research in the response.

SUMMARY

From the outset of the committee’s work, we have focused on the goal of identifying ways to improve the speed and effectiveness of clinical research during an epidemic of an emerging infectious disease. This has involved the committee considering the many complex issues that are at the core of good clinical research. We have been aware of the multiplicity of issues that impinge on the task of optimizing clinical research in these circumstances. As discussed in greater detail in the preceding chapters, clinical trials require a diverse range of expertise, from scientific and medical experts to those who are adept at law, ethics, and community engagement. It is not possible to consider how to improve the speed and efficiency of clinical research on an emerging infectious disease without reflecting on the need to determine that an outbreak is beginning or that a new or neglected agent is emerging; the first step in the chain is to have effective and sustainable surveillance in place within countries, connected to a global community with expertise and resources to deploy once the need is identified and a response is triggered. The world can certainly do better in this regard than it has up until now. The next step in the chain is to be certain that there is the vision, expertise, and resources to support essential early research on priority pathogens spanning the spectrum from discovery, pathogenesis, and early R&D on diagnostics, drugs, and vaccines.

Due to the complexity of the activities involved in the design and conduct of trials, their implementation in the midst of a rapidly progressing outbreak requires quick action and immense coordination and collaboration among stakeholders, from the countries affected to the international community involved in the global response. Developing a document database for research (as discussed in Chapter 5) that includes model documents for all of the administrative processes required for approval and implementation of clinical research in these circumstances, that has a variety of model research designs available to be adapted to the particular attributes of the agent and the outbreak, and that includes the tools for ethical and legal review would help to strengthen research systems and guide affected countries to more quickly understand the lifespan of the research process and be better equipped to act as effective partners. In order to be rapidly

effective when an outbreak is recognized, the health care, public health, and health research communities will require training in the nature and use of these tools. This is why the committee is convinced that coordinated planning and capacity strengthening for clinical research must start in the inter-epidemic period and why research must continue to be considered a critical part of the response as an outbreak begins and the initial response teams enter the affected communities. Engaging the community at every step is essential in order to avoid conflicts, to establish trust, and to prevent problems that may lead to premature trial closure, or prevent them from ever beginning (Folayan et al., 2015).

If national and international researchers can work together on a collaborative and coordinated research agenda, and include input from the population at risk, the global community has the best chance at being prepared for the next outbreak. As Louis Pasteur said a long time ago, “Chance favors the prepared mind” (Pasteur, 1854). It can also be said that preparation is not without cost, in fact significant sums are required; however, considered as an investment in global health and security these amounts pale in the comparison to the cost of confronting an epidemic and the potentially catastrophic loss of life and global resources if we are unprepared, uncoordinated, and without global participation.

REFERENCES

Brende, B., J. Farrar, D. Gashumba, C. Moedas, T. Mundel, Y. Shiozaki, H. Vardhan, J. Wanka, and J.-A. Røttingen. 2017. CEPI - A new global R&D organisation for epidemic preparedness and response. The Lancet 389(10066):233–235.

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2014. U.S. commitment to the global health security agenda: Toward a world safe & secure from infectious disease threats. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/security/pdf/ghs_us_commitment.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

CEPI (Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations). 2016a. CEPI: Approach. http://cepi.net/approach (accessed January 25, 2017).

CEPI. 2016b. CEPI: Partners. http://cepi.net/partners (accessed January 25, 2017).

CEPI. 2016c. CEPI newsletter, November 21. http://cepi.net/sites/default/files/52016.pdf.

CEPI. 2017. Global partnership launched to prevent epidemics with new vaccine. http://cepi.net/cepi-officially-launched (accessed February 20, 2017).

Chiappelli, F., A. Bakhordarian, A. D. Thames, A. M. Du, A. L. Jan, M. Nahcivan, M. T. Nguyen, N. Sama, E. Manfrini, F. Piva, R. M. Rocha, and C. A. Maida. 2015. Ebola: Translational science considerations. Journal of Translational Medicine 13:11.

Cohen, J., and M. Enserink. 2015. Special report: Ebola’s thin harvest. Science, December 31. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/12/special-report-ebolas-thin-harvest (accessed January 26, 2017).

DiMasi, J. A., H. G. Grabowski, and R. W. Hansen. 2016. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics 47:20–33.

Ebola Vaccine Team B. 2017. Completing the development of Ebola vaccines: Current status, remaining challenges, and recommendations. Regents of the University of Minnesota. http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/sites/default/files/public/downloads/ebola_team_b_report_3-011717-final_0.pdf (accessed February 20, 2017).

Folayan, M. O., K. Peterson, and F. Kombe. 2015. Ethics, emergencies and Ebola clinical trials: The role of governments and communities in offshored research. The Pan African Medical Journal 22(Suppl 1):10.

Gelinas, L., H. F. Lynch, B. E. Bierer, and I. G. Cohen. 2017. When clinical trials compete: Prioritising study recruitment. Journal of Medical Ethics 0:1–7.

GHSA (Global Health Security Agency). 2014. Global Health Security Agenda: Action packages. https://www.ghsagenda.org/packages (accessed January 26, 2017).

GHSA. 2016a. Global Health Security Agenda: Membership. https://www.ghsagenda.org/members (accessed January 26, 2017).

GHSA. 2016b. Global Health Security Agenga: About. https://www.ghsagenda.org/about (accessed January 26, 2017).

Gostin, L. O., and R. Katz. 2016. The International Health Regulations: The governing framework for global health security. Milbank Quarterly 94:264–313.

Grant, K. 2014. How Canada developed pioneer drugs to fight Ebola. The Globe and Mail, August 22. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/health/how-canada-developed-pioneer-drugs-to-fight-ebola/article20184581 (accessed January 26, 2017).

Head, M. G., J. R. Fitchett, V. Nageshwaran, N. Kumari, A. Hayward, and R. Atun. 2016. Research investments in global health: A systematic analysis of UK infectious disease research funding and global health metrics, 1997–2013. EBioMedicine 3:180–190.

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee. 2016. Science in emergencies: UK lessons from Ebola: Second report of session 2015–16. Report No. HC 469. London, UK: House of Commons. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmselect/cmsctech/469/46902.htm (accessed January 26, 2017).

Kieny, M. P., J.-A. Rottingen, and J. Farrar. 2016. The need for global R&D coordination for infectious diseases with epidemic potential. The Lancet 388(10043):460–461.

Kelland, K. 2015. INSIGHT–MERS, Ebola, bird flu: Science’s big missed opportunities. Reuters, October 26. http://www.reuters.com/article/health-epidemic-research-idUSL8N12831D20151026 (accessed January 27, 2107).

Kliff, S. 2014. No, budget cuts aren’t the reason we don’t have an Ebola vaccine. Vox, October 16. http://www.vox.com/2014/10/16/6987825/ebola-budget-nih-collins-vaccine (accessed February 1, 2017).

Kupferschmidt, K. 2015. Scientists argue over access to remaining Ebola hotspots. Science, March 26. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/03/scientists-argue-over-access-remaining-ebola-hotspots (accessed January 26, 2017).

Marais, D., J. Toohey, D. Edwards, and C IJsselmuiden. 2013. Where there is no lawyer: Guidance for fairer contract negotiation in collaborative research partnerships. Geneva, Switzerland: Council in Health Research for Development. http://www.cohred.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Fair-Research-Contracting-Guidance-Booklet-e-version.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

Moran, M., N. Chapman, L. Abela-Oversteegen, V. Chowdhary, A. Doubell, C. Whittall, R. Howard, P. Farrell, D. Halliday, and C. Hirst. 2015. Neglected disease research and development: The Ebola effect. Sydney, Australia: Policy Cures. http://policycures.org/downloads/Y8%20GFINDER%20full%20report%20web.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

Nature. 2017. Vaccine initiative marks bold resolution. 436.

NCI (National Cancer Institute). NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms?cdrid=561321 (accessed March 8, 2017).

Pasteur, L. 1854. Inaugural address as newly appointed professor and dean (Sep 1854) at the opening of the new Faculté des Sciences at Lille (7 Dec 1854). https://todayinsci.com/P/Pasteur_Louis/PasteurLouis-Quotations.htm (accessed January 26, 2017).

PHE (Public Health England). 2016. UK team of health experts to tackle global disease outbreaks. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-team-of-health-experts-to-tackle-global-disease-outbreaks (accessed January 26, 2017).

Policy Cures. 2017. G-FINDER. http://policycures.org/gfinder.html (accessed February 20, 2017).

PREVAIL II Writing Group. 2016. A randomized, controlled trial of ZMapp for Ebola virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine 375(15):1448–1456.

Ross, E. 2017. Ebola funding surge hides falling investment in other neglected diseases. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.21505.

Røttingen, J.-A. 2016. Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI): Presentation to the WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/medicines/ebola-treatment/TheCoalitionEpidemicPreparednessInnovations-an-overview.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

Røttingen, J.-A., D. Gouglas, M. Feinberg, S. Plotkin, K. V. Raghavan, A. Witty, R. Draghia-Akli, P. Stoffels, and P. Piot. 2017. New vaccines against epidemic infectious diseases. New England Journal of Medicine 376(7):610–613.

Schopper, D., R. Ravinetto, L. Schwartz, E. Kamaara, S. Sheel, M. J. Segelid, A. Ahmad, A. Dawson, J. Singh, A. Jesani, and R. Upshur. 2016. Research ethics governance in times of Ebola. Public Health Ethics phw039. doi: 10.1093/phe/phw039. https://academic.oup.com/phe/article-abstract/doi/10.1093/phe/phw039/2548977/Research-Ethics-Governance-in-Times-of-Ebola?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed February 1, 2017).

USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development). 2016. Emerging Pandemic Threats 2 Program. https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/fact-sheets/emerging-pandemic-threats-program (accessed January 25, 2017).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2015a. Follow up to the World Health Assembly decision on the Ebola virus disease outbreak and the Special Session of the Executive Board on Ebola: Roadmap for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. http://www.who.int/about/who_reform/emergency-capacities/WHO-outbreaks-emergencies-Roadmap.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

WHO. 2015b. Outcome document: Financing of R&D preparedness and response to epidemic emergencies. October 29–30, 2015. Oslo, Norway, and Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. http://www.who.int/medicines/ebola-treatment/Outcome.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

WHO. 2015c. WHO leadership statement on the Ebola response and WHO reforms. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/joint-statement-ebola/en (accessed January 25, 2017).

WHO. 2016. A research and development blueprint for action to prevent epidemics: Plan of action. May 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. http://www.who.int/csr/research-and-development/r_d_blueprint_plan_of_action.pdf?ua=1 (accessed January 26, 2017).

WHO. 2017. IHR Committees and expert roster. http://www.who.int/ihr/procedures/ihr_committees/en (accessed February 20, 2017).