6

Engaging Communities in Research and Response

Clinical research entails a special relationship between researchers and the communities of the research participants. The research participants volunteer themselves to consent to and take part in the research. Participants at the time of consent can not only be ill, but often fearful, hopeful, vulnerable, expectant, reluctant, and at times confused about goals, benefits, and risks—and sometimes several or all of these simultaneously. Response to an emergency of any nature, be it health or a natural disaster, is difficult, demanding, dangerous, and often unravels under conditions that preclude effective dialogue between those in need and those providing help. Conducting clinical research in the midst of a public health emergency like the Ebola epidemic in 2014–2015 involved most, if not all, of these issues and concerns. This is the fundamental reason why engaging affected communities in all facets of epidemic response is critical to ensuring that the response to the emergency is successful—for example, that community members not only receive and understand public health messages, but that they seek out and trust clinical care, and become engaged to help shape the epidemic response and actively contribute to the efforts to change behaviors in order to protect people from exposure and facilitate getting those infected into care, as well as to become active participants in research. To create the special relationship required for clinical research to go forward, there must be trust and respect built between the researchers, the community, and the individual participants (Ahmed and Palermo, 2010; Nyika et al., 2010).

Community engagement is as much an essential component of the clinical research process when research is being conducted in developed

countries—especially among marginalized populations—as it is in developing country settings, but research in the latter particularly when working with marginalized populations may be complicated by different social and cultural perceptions; differences in language and meaning; and asymmetry in authority, expertise, and resources between the researchers and the local participants (Berndtson et al., 2007; CIOMS, 2016; McMillan and Conlon, 2004; NBAC, 2001; Wellcome Trust, 2011). In West Africa there is a vivid history of exploitation by government and international actors, from the slave trade and colonialism of the past to more modern-day civil wars, and disputes over trade policy and resource extraction. There is also a history of unethical and paternalistic medical research on the population by international researchers. Community suspicions that researchers’ actions are hiding malicious intent is supported by a collective memory of a lack of informed consent during past research, and this needs to be recognized and overcome (Okonta, 2014).

Communities need to be engaged from the onset of an outbreak response, have access to accurate information about what is happening to individual members of the community and what is happening to them collectively, and have a way to get reliable answers to questions (Kickbusch and Reddy, 2015). There are a variety of ways to share information with community members, depending on the urgency and gravity of the event, including but not limited to one-on-one interviews, town meetings, focus group discussions, community surveys, dissemination of information via the media, and setting up Community Advisory Boards (Nyika et al., 2010). To truly engage communities, they should also be invited and encouraged to be involved in planning and strategy committees for outbreak response and participate in monitoring and evaluation of the outbreak response and clinical trials.

The range of meaningful community engagement activities includes informing, consulting, involving, collaborating, and partnering with communities and also contributing to citizen-led strategies (DELWP, 2013). Community engagement strategies generally involve structured approaches to sharing information, collaborative problem solving, collective action, participation in decision making and transparent accountability with community leaders and stakeholders, along with formal government authorities (George et al., 2015). These steps are not necessarily familiar to researchers who more likely than not have limited experience in community engagement and lack relevant training in the subject. Nonetheless, in order to effectively engage the community, research teams need to successfully link with community members and leaders; this may require bringing someone onto their team who has the necessary skillset and experience, for example, an anthropologist or other social scientist.

Engaging the community serves a number of purposes for epidemic response and research. These include building the knowledge base and

capabilities of the community so they understand what the emergency is, what can be done, and what needs to be learned. Incorporating the priorities and perspectives of the community into epidemic response and research plans builds trust and bolsters community confidence in the clinical researchers, both local and international. This serves as a prelude to successfully recruiting them to become involved in clinical trials (Kickbusch and Reddy, 2015; Laverack and Manoncourt, 2015) (see Box 6-1).

During the Ebola epidemic, a lack of early and sustained community engagement efforts hampered both the response and research efforts (Bedrosian et al., 2016). However, as community engagement improved and communities became more knowledgeable and involved, both of these endeavors benefited. For example, communities came to accept randomized controlled trials, an outcome that had seemed impossible in the beginning (Doe-Anderson et al., 2016). A critical factor in this acceptance was the connection and dialogue between health care and research communities, traditional and religious leaders, civil society organizations, women’s groups, survivors, and other trusted members of communities who could effectively communicate within the community and who understood how

to shape culturally sensitive messages and explain response measures and research activities. The experience in West Africa has clearly demonstrated that in any future outbreaks, disasters, or other public health emergencies in which research needs to be conducted, it will be critical that community engagement is begun early and done well.

ENGAGING COMMUNITIES IN RESPONSE

Empirical studies from cholera, shigellosis, dengue, and other outbreaks demonstrate the centrality that communities play in outbreak response and control (Kickbusch and Reddy, 2015). They reveal that understanding local communities’ customs, beliefs, knowledge, and practices is essential to the success of disease prevention and treatment interventions as well as of biomedical approaches (Chang et al., 2011; Connolly et al., 2004; Faruque et al., 1985; Mohle-Boetani et al., 1995). The Ebola outbreak was particularly difficult to initially control because it took place in an environment of preexisting mistrust of external responders (both medical care providers and researchers) as well as national and local political authorities (Mukpo, 2015). Rumors began to spread that Ebola was “deliberately propagated as a way for entrenched interests to pocket money donated for the response” (Dhillon and Kelly, 2015, p. 788). It led some community members who were ill to avoid seeking care at health care facilities or Ebola treatment units (ETUs) and instead to visit traditional healers to treat their illness, in part because some believed Ebola was caused by witchcraft (Bedrosian et al., 2016). One study in Liberia revealed that the majority of the population surveyed were afraid of ETUs; individuals reported a fear that they would not be allowed to see their families if they were admitted to an ETU or that they would die if they sought care at one (a concern often confirmed given the high mortality rates in the ETUs) (Kobayashi et al., 2014). It is not surprising that community members at times “defied recommendations from public health authorities because of fear that those authorities were responsible for spreading Ebola” (Bedrosian et al., 2016). A news analysis article in The New York Times reported that “The notion, for example, that health officials are conspiring with Big Pharma to consciously spread—and then cure—Ebola as a profit-making venture might sound like the plot to a cheesy summer thriller, but in fact it touches on a genuine aspect of our health care system, said Mark Fenster, a professor at the University of Florida’s Levin College of Law and the author of Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture” (Feuer, 2014). Others noted that “While health workers are struggling to contain the outbreak, conspiracy theories about the deadly pandemic are proliferating on the internet, with people deeming the virus a creation of the West to annihilate Africans or as the result of bioterrorism activities” (Iaccino, 2014). The trust in

the Ebola response was further eroded when patients in ETUs, isolated from family and friends, encountered health care workers in their eerie yellow personal protective equipment, which served to hide every visible clue to their humanity except their eyes, leaving little to no possibility for an empathetic connection (Fast, 2015). A redesign of personal protective equipment, with a clear circumferential head cover so the provider’s face is visible and with a place for the individuals name on the front and the back, is long overdue (King, 2014).

Early missteps in community engagement and communication exacerbated these issues of mistrust, rumors, and fear. Despite prior knowledge of the effectiveness of community engagement in outbreak response, national authorities and international responders were slow to involve communities in the planning of public health interventions and in developing and implementing communication and social mobilization strategies during the Ebola outbreak (Laverack and Manoncourt, 2015; Marais et al., 2016) The initial response strategy was reported to be “top-down and driven by epidemiological data and the perceived need to treat Ebola patients” (Laverack and Manoncourt, 2015, p. 2) and the initial control measures did not take into account deep-rooted community traditions and beliefs or basic community needs in the West African setting (Laverack and Manoncourt, 2015). For example, mandatory cremation policies countered deeply held religious beliefs about proper burial of the dead and quarantine requirements led to food shortages and disrupted trade (Abramowitz et al., 2015).

However, over the course of the epidemic, communication and social mobilization improved, and with that the situation on the ground improved. As Laverak and Manoncourt observed, “The lead agencies did learn from their earlier mistakes in the present outbreak and have made a genuine attempt to better engage with communities” (Laverack and Manoncourt, 2015, p. 82). There were many examples of improved engagement. A group of anthropologists working in the region, for example, developed the Ebola Response Anthropology Platform to share knowledge and information about the affected communities and community-led responses in real time (Ebola Response Anthropology Platform, 2017). In Liberia, “Community leaders set up response teams (Ebola task forces) to lead contact tracing, case investigation, and reporting, as well as surveillance. The community-based Ebola task force also instituted quarantine measures and provided food and water for those confined to their homes” (Wilson et al., 2016). When the Ministry of Health in Liberia recognized how successful this community-based approach was it provided formal support to the efforts. An important, perhaps critical, step was consultations with traditional and religious leaders to incorporate faith elements into public health messages and providing examples from religious texts to support them. With these types of collaborations, there was significant improvement of community

perceptions of key messages. For example, the committee heard from a local reverend who helped control efforts by assuring his community that the traditional practice of “laying of hands” believed to help cure the sick could be done spiritually at a safe distance and still meet religious requirements.1 The National Traditional Council in Liberia, with support from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), engaged in efforts to persuade communities to heed public health messaging (Global Communities, 2015). Provided with bullhorns, buckets, and bleach, the local tribal chiefs and elders went from village to village to demonstrate how people can help to stop the transmission of Ebola (Act Alliance, 2014). Another community-based approach was the creation of Community Care Centers (CCCs) led by Liberian county health officials and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). CCCs were established so that patients who were awaiting Ebola diagnostic tests or entry into ETUs could be admitted and provided with basic care, but also helped to destigmatize Ebola and to encourage persons with illness to seek care rather than remain at home. In addition, these centers facilitated contact tracing of exposed family members (Logan et al., 2014). These modifications to the response were intended to convey critical information and engender trust from the community and thereby improve the community’s participation in the efforts to slow the spread of Ebola. It seems likely that if such initiatives to engage and share information were commenced earlier, and community participation in planning and implementing response and research programs were prioritized, it might have greatly affected the communities’ receptivity to clinical trials. The fear and mistrust generated by poor initial community engagement in response activities had a direct impact on the real and perceived feasibility of conducting clinical trials during the epidemic.

Marais et al. have proposed an eight-step process for engaging communities during outbreaks, which could be adapted for future scenarios (Marais et al., 2016). Many of their steps focus on the need to identify and partner with key trusted leaders, both men and women, including village or traditional chiefs, religious leaders, traditional healers, community health workers, and others who have the respect of community members. They provide a critical observation: “Low-resource communities around the world are accustomed to meetings called by outsiders, in which they are informed of a new health threat and the need to comply with directions. Such meetings are often poorly attended and sometimes promote fear or further feelings of disconnect between health authorities and local residents” (Marais et al., 2016, p. 444). The EBOVAC-Salone team discovered this in the process of implementing their vaccine study when they were approached by a small group of stakeholders from the community who had

___________________

1 Presentation of Reverend John Sumo. Public Workshop of the Committee on Clinical Trials During the 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak, Monrovia, Liberia, August 16, 2016.

attended their information meetings but did not feel they could express their concerns in public (Enria et al., 2016). They recommend instead having community leaders organize meetings with a few medical or research team members invited as guests. At these meetings, community members could map assets (e.g., faith-based groups, traditional healers, local radio stations, schools, health centers, youth leaders, and elders) that can help promote public health measures or research activities and identify gaps in community resources and risks. It was essential to recognize that “community members may help facilitate a process of turning problems into assets, [for example] when nursing and medical students in Sierra Leone whose schools were closed went on bicycles to find new Ebola cases” (Marais et al., 2016, p. 444).

Conclusion 6-1 At the beginning of an outbreak it is critical that national and international agencies engage key community representatives, religious and traditional leadership, and others working in the community, such as nongovernmental organizations, faith-based organizations, and civil society organizations, to establish communication to foster mutual trust and a partnership for response and research activities.

ENGAGING COMMUNITIES IN RESEARCH

During the Ebola outbreak some community members believed they were being used as “guinea pigs” for foreign researchers. “A local radio reporter asked whether signing a consent form was tantamount to a ‘death warrant’ for volunteers. A daily newspaper said simply, ‘Liberians are not animals.’ Scientists have been left scrambling to win over the trust of the Liberian people on the ground” (Onishi and Fink, 2015). In this environment, the importance of community engagement cannot be overstated. Wilson et al. comment that “When communities are not involved from the beginning, they feel like objects of the research rather than partners in the process, thereby leading to distrust, poor communication, rumors, and misconceptions, all of which negatively impact the process and ultimately the outcome of the research” (Wilson et al., 2016).

As discussed in earlier chapters, research activities were not considered in the early months of the epidemic, and once they were, there was tremendous pressure to launch trials as rapidly as possible. This urgency did not leave adequate time for research teams to engage communities in the initial phase of trial planning and led to disagreements about what communities would or would not accept at the WHO meetings, particularly in relation to trial design. Folayan et al. observed of the plans in place to conduct trials on therapeutics and vaccines that “the timelines are so short that the prospect for effective community engagement is dismally low despite the now strong recognition to effectively engage local communities in the clinical research

process” (Folayan et al., 2015, p. 1). Research teams had varying knowledge and experience on community engagement prior to the outbreak, but all quickly understood the importance of consulting with communities on all aspects of the research proposal prior to initiating trials. The below section describes the engagement activities of several of the teams and the lessons they learned in the process.

Community Input on Research

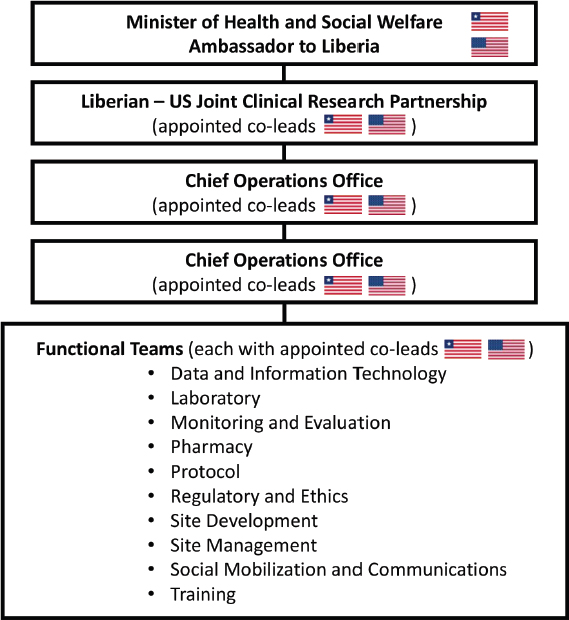

Research teams seeking to investigate Ebola therapeutics or vaccines initially sought approval from the appropriate regulatory authorities and advisory bodies, but in some cases did not obtain local community opinions or input in the research planning phase. According to Nyika et al., one reason that community engagement is so important is that “relying solely on the approvals from local ethics committees and regulatory authorities and high-level technical advisory bodies without any practical efforts to interact directly with ordinary communities may in the long run prove to be unsatisfactory to the communities concerned and other stakeholders” (Nyika et al., 2010, p. 3). This point was illustrated when the Partnership for Research on Ebola Vaccines in Liberia (PREVAIL) trial was launched (NIAID, 2015). The trial was initially requested by Liberia’s Minister for Health and Social Welfare in an official letter to the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services. The response was rapid, and the U.S. and Liberian government agencies quickly established a working partnership (see Figure 6-1). The resulting research proposal received the required regulatory and ethics approvals in country. But it was subsequently held up due to a challenge by a group of Liberian politicians, lawyers, human rights activists, ethicists, journalists, and academicians who “were opposed to the concept of conducting clinical research with inadequate health care facilities, in a research naïve population, during an ongoing public health crisis” (Doe-Anderson et al., 2016, p. 70). According to Dr. Vuyu Golokai, at the time the Dean of the Dogliotti College of Medicine in Monrovia, the fact that research authorization came from high-ranking political authorities (i.e., the President) inhibited local scientists and community members from voicing dissent (Sendolo, 2016). Stephen B. Kennedy, the coordinator for Ebola research and the Incident Management System in the Liberian Ministry of Health, admitted at a press conference in Monrovia that several actions were missed along the way before the trials began. Kennedy said, “We failed to carry out (comprehensive) consultations. For example, we left out the media, the legislature, women and other important groups in our consultation process during the planning stage. . . . We are not politicians; we are medical people, and so we were not sensitive enough to these procedures. We only took into consideration the medical community during

SOURCE: Doe-Anderson et al., 2016.

the initial process. However, we will do all we can to meet those concerns that are being raised” (Yates, 2015). Dr. Clifford Lane, the deputy director for clinical research and special projects and the director of the Division of Clinical Research at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, reflected in the context of clinical research initiatives in Liberia: “This concept of social mobilization, I had not heard that term before. But I came to realize it is one of the most critical things for success in this country” (Onishi and Fink, 2015).

Subsequently, the PREVAIL team held a series of meetings initiated by the Liberian vice president, where concerns were expressed about issues such as informed consent, inadequate testing of the vaccines in humans, the possibility of giving false hope to an at-risk population, and the potential that participants were being exploited or coerced (via compensation) to help develop a lucrative vaccine for the manufacturer. While dissenting voices remained, the study was ultimately approved through hard work and after extensive dialogue in the community to address the many questions

and concerns raised, and through crafting simple yet comprehensive messages about informed consent and the risks and benefits of participating. Additional stakeholder meetings resulted in an agreement that research participants would have post-trial access to any vaccines and treatments that were proven effective (Doe-Anderson et al., 2016).

Even with these insights, the PREVAIL trial team reported that it took 3 months of intense engagement with communities to achieve the goal of 1,500 consented participants. This entailed a multipronged approach including meetings with national stakeholders and local leaders within target communities to collect information about community concerns and to better understand cultural, religious, and traditional norms. For example, team members learned that they should use the word “study” instead of “trial,” because the latter connoted experimentation on animals in local understanding and thus would be negatively received. The trial also hired participant trackers from the community to assist with follow-up; as Wilson et al. (2016) commented, “the role played by these trackers in promoting behavior change to build lasting trust and sustainable relationships within these communities cannot be overemphasized” (Wilson et al., 2016).

The CDC-supported Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine against Ebola (STRIVE) team also spent significant time and resources engaging with communities (CDC, 2015). Prior to presenting the study to the full government and the media, leaders from the Ministry of Health in Sierra Leone and the College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences “conducted numerous outreach sessions with traditional and religious leaders of selected chiefdoms, district health leaders, and professional organizations to explain the proposed trial, to understand concerns, and to garner support and feedback. Study team members also met with leaders of every eligible health facility” (CDC, 2016). The STRIVE team reported holding 175 informational sessions in sites where the vaccine trial was held, using materials developed during the initial engagement phase. Participants were presented with consent forms at the information session, but they also had 24-hour access to a hotline with trained staff to answer questions about the trial and procedures (Widdowson et al., 2016).

In the case of the Guinea ring vaccination trial (also known as Ebola ça Suffit), social anthropologists provided advice to the trial team on appropriate communication channels and methods to approach communities. The team employed community facilitators, who spoke the local language, to explain the purpose of the trial and answer questions regarding concerns about potential harm from the vaccine.2

___________________

2 Testimony of Ana Maria Henao Restrepo, Medical Officer, Department of Immunization Vaccines and Biologicals, WHO. Public Workshop of the Committee on Clinical Trials During the 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak, London, UK, March 22–24, 2016.

The EBOVAC-Salone trial first trained a community liaison team, comprised of locally recruited staff, on the basics of clinical trials. The initial phase of the community engagement strategy was a 2-month process that included individual consultations with key stakeholders (e.g., elected leaders, traditional leaders), and a series of public meetings hosted with local civil society members and traditional leaders. Additionally, the team conducted “house-to-house sensitization visits” and participated in a local call-in radio show. Finally, the team recruited four local research assistants “to examine community and participant perceptions and experiences of the EBOVAC-Salone vaccine study, including any rumors and concerns about the trial and vaccine” (Enria et al., 2016, p. 4). A subsequent paper published about the EBOVAC-Salone trial underscores the important role of social science and community liaison teams to shape engagement and communication strategies. It also highlighted that community engagement and communication needs—including risk and rumor management—be anticipated, and strategies and funding be included in research plans (Enria et al., 2016).

Community engagement can help facilitate community understanding of key research objectives and concepts and reduce misunderstandings about research. It is clear from the experiences of the researchers involved in clinical trials during the Ebola outbreak that community engagement requires extensive dialogue with key community representatives on complex issues such as study design, the potential benefits and risks of investigational vaccines or therapeutics, and fair distribution of benefits to participants and communities (see Table 6-1). But by giving communities the opportunity to share perspectives and provide input on these issues, researchers can adapt study protocols and clinical trial agreements to address community concerns when possible, and when such adaptations are not technically feasible can continue the conversation to improve understanding.

As detailed earlier in this report, there was much debate among researchers and stakeholders over what would or would not be considered acceptable to the communities that would be participating in the clinical trials, without necessarily understanding the basis for community perceptions. According to a report from the Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm)3 and the French Institute for Development Research, national health officials, Médecins Sans Frontières, and national caregivers argued that communities would not understand or accept certain design features, such as randomization (Botbol-Baum et al., 2015). However, the committee heard testimony in Liberia that local community representatives were largely not included in early discussions about trial design. For example, Mandy Kader Konde, a professor at the University

___________________

3 Inserm is the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research.

| Consulting the Community to Negotiate Research Benefits | Steps and Considerations |

|---|---|

| Which community? |

Identify the community according to community characteristics. Identify degree of community involvement in research. Study the chosen community with regard to sociocultural structure and political/traditional leadership. |

| Which community representatives? |

Identify legitimate representatives of the community, and do not reinforce existing inequitable structures and relationships, such as gender inequities. |

| How to negotiate? |

Provide information about the research. Assess risks, burdens, and benefits for individual participants, the community, and sponsors. Provide information about previous benefit agreements. Provide support for negotiations. Recognize that benefit negotiations are dynamic. |

| What comes next? |

Make benefit agreements publicly available. |

SOURCE: Schulz-Baldes et al., 2007.

of Conakry and chairman of the Department of Public Health as well as chairman of the Guinea Ebola Research Commission and executive director of the Center of Research on Diseases (CEFORPAG), stated that time was lost in high-level discussions around facets of trial design, such as randomization and the use of placebos, without ever discussing these features directly with the community. With effective community engagement and articulation of aspects of trial designs, community buy-in is possible. This has been clearly demonstrated by the community acceptance of and participation in the PREVAIL randomized controlled trial. The PREVAIL team reported successfully describing randomization using flip charts and local terms, after consulting with local people to determine the common parlance for randomization, for example “lucky ticket” or “eeny-meeny-miny-moe,” and they reported that through using local colloquial phrasing, participants had an increased understanding of the process.4

Respect for communities requires that communities be engaged in a process of dialogue about the need for research, the nature of the uncer-

___________________

4 Testimony of Elizabeth Higgs, global health science advisor, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Public Workshop of the Committee on Clinical Trials During the 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak, Washington DC, June 13–15, 2016.

tainty to be addressed, what is known about the status of the interventions to be used, including benefits and risks, and the merits and limits of possible trial designs. In a context of scarcity, need, and heightened mistrust, as in the midst of the epidemic, these conversations can be challenging—but they are an indispensable component of ethically sound research and are critical to treating study communities as full partners in the effort to find ways to improve the community members’ health.

Conclusion 6-2 National-level agreements with international researchers for the conduct of clinical trials during an epidemic do not necessarily indicate local acceptance or understanding of the research activities. Affected communities may have legitimate concerns about research that national authorities do not fully recognize.

Conclusion 6-3 Community engagement and social mobilization efforts are essential for public understanding and acceptance of research, and they need to be linked to other aspects of the epidemic response. International response and research teams would be strengthened by the inclusion of social scientists and others with expertise in community engagement. In addition, and ideally, researchers and responders should receive training in (1) cultural competency, (2) rapid appraisal techniques to identify key individuals and groups who influence local opinion, and (3) methods to assess affected populations’ understanding of and concerns regarding clinical research and how they can participate in the research.

Individual and Community Consent

A key component of clinical research is obtaining the informed consent of participants. While U.S. requirements for informed consent focus almost entirely on individual autonomy and individual consent, some cultures consider the community’s perspective to be a “fundamental aspect of individual decisions” (Diallo et al., 2005, p. 255). International research guidelines have increasingly reflected this cultural difference, noting that researchers should respect local customs such as “obtaining permission from a community leader, a council of elders, or another designated authority” (Diallo et al., 2005, p. 255). However, it should also be clear that while community consent may be an important or necessary first step to obtaining individual consent, it cannot replace individual consent. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration guidance states, “Community consent is not a substitute for individual informed consent required under the IND/IDE regulations, nor can the community consent on behalf of individual members to permit their participation in a study” (HHS, 2016).

The committee considered the following questions on consent pertinent to its charge: first, what if any type of community consent was obtained; second, were the individual consent processes designed to enable the population to understand the nature of the research; third, to what extent was obtaining meaningful informed consent difficult because of the conditions under which the process was carried out; and fourth, in future, similar epidemics, is it appropriate to alter or waive any consent requirements? Ideally, researchers would receive consent from both communities and individuals, in whatever manner is appropriate for the specific cultural traditions and understanding of the community. For example, a malaria vaccine trial in Mali sought the consent of the community in addition to individual consent before initiating research (Diallo et al., 2005). They held introductory meetings with health authorities and government officials, followed by formal meetings with neighborhood and religious leaders and traditional practitioners. The researchers visited community leaders in their homes to further explain the study and to answer any questions, and these leaders in turn transmitted information to the general population. In keeping with community traditions about formal agreements, researchers documented the community consultation and consent process through meeting minutes, which were signed by top community leaders. The researchers found that obtaining community consent through this process had a number of practical and ethical benefits: it ensured widespread knowledge about the research project, avoided potential resistance from local leaders, facilitated referrals of patients through traditional practitioners, and reassured community members that their leaders were comfortable with the project. With the consent of the community, obtaining individual consent became easier. During the Ebola epidemic, it was unclear to the extent in which community consent was obtained, though as detailed above, trial teams did hold group sessions and meetings to address community concerns prior to enrolling participants. For example, the PREVAIL trial team held group information sessions in which they discussed the plans for the study. Following those sessions, those who were interested in participating went through an individual consent process, and, as in the STRIVE trial, they were provided with 24-hour access to a hotline with trained staff to answer questions about the trial and procedures (Widdowson et al., 2016).

Participant comprehension is critical to the informed consent process, which means that while written documentation of consent is required, it is not enough to merely obtain a signature. The researcher must ensure that participants are adequately informed, have voluntarily agreed to participate, and understand that their consent may be withdrawn at any time without affecting their access to care (HHS, 2016). There are well-recognized issues with obtaining informed consent that may particularly occur with complex research designs and low-literate populations. Dur-

ing the Ebola epidemic these issues were especially pronounced given the distinctive (though not necessarily unique) circumstances detailed above—the pervasive sense of urgency; fear and distrust of authority and foreign researchers; little prior experience with clinical trials; critically ill patients that were occasionally too sick or delirious to give consent; and lack of time for caregivers to spend with patients. Long multipage forms using technical language and long lists of potential adverse effects, which are often used for consent for clinical research in high-income countries, are difficult to navigate, even by literate, educated trial participants.5 The Nuffield Council addresses these points, noting that “consent forms often appeared to be designed to protect researchers and their sponsors rather than participants. The forms [are] frequently too long and complex, making them inaccessible to participants” (Nuffield Council on Bioethics, 2002, p. 15). During her discussions with the committee, Luciana Borio, acting chief scientist at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, welcomed the suggestion of shortened consent forms that use clear and simple language, reducing the unnecessary jargon and lists that are so often used to cover liability concerns and satisfy legalistic institutional review board (IRB) imposed requirements in affluent countries.6 The consent forms from the trials the committee reviewed were generally three to four pages in length.7

The consent process needs to be conducted in the language of the participants. However, the translation of forms into local languages may add to the confusion when concepts are not clearly stated and mistranslations result in a different meaning than intended (Chaisson et al., 2011; Samandari et al., 2011). Back translation to ensure that the original meaning has been maintained is therefore beneficial (Jhanwar and Bishnoi, 2010). In low-literacy settings, consent form language may be accompanied by the use of pictorial aids to convey the complex processes that are described. For example, in one study, a multimedia informed consent tool demonstrated improved comprehension and retention among low-literate study participants (Afolabi et al., 2015). The EBOVAC-Salone trial developed a flipchart to facilitate discussion between researchers and potential participants which included a number of pictures that illustrated the points in the consent

___________________

5 Testimony of Ana Maria Henao Restrepo, Medical Officer, Department of Immunization Vaccines and Biologicals, WHO. Public Workshop of the Committee on Clinical Trials During the 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak, London, UK, March 22–24, 2016.

6 Testimony of Luciana Borio, acting chief scientist, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Public Workshop of the Committee on Clinical Trials During the 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak, Washington, DC, February 22–23, 2016.

7 Consent forms were obtained through personal communication with several trial teams: Peter Horby, University of Oxford (RAPIDE-BCV and TKM-Ebola); Dennis Malvy, University of Bordeaux (JIKI); James Neaton, University of Minnesota (PREVAIL).

form.8 In the Guinea ring vaccination trial, the team ensured that illiterate participants had an independent literate witness to provide consent in writing. While informed consent processes should be flexible and appropriate for the population and situation, it should also be recognized that some potential participants (e.g., those who may be forcibly confined or noncompetent patients without an available proxy) may simply not be suitable candidates for research studies because they are not able to give consent.

In emergency situations, however, it may be worth considering when an exception of informed consent may apply. Exception from informed consent allows researchers to enroll patients in certain emergency situations where consent cannot be given in advance, available treatments are unproven or unsatisfactory, and the research in question cannot be carried out without this waiver of informed consent. While this exemption facilitates the ease of enrollment of patients, it also requires the commitment of time and resources by the investigator, sponsor, and scientific and ethics review boards to ensure that potential host communities are openly and honestly informed about the risks and potential benefits associated with participation and given the opportunity to accept or decline to host the study in question. Even when communities are willing to host such studies, individuals may not wish to be included. Opt-out mechanisms, such as a wristband or bracelet, are often an ethics board or sponsor-required component of these studies and provide community members with the opportunity to indicate their prospective refusal to give consent to participation (HHS, 2013).

THE ROLE OF COMMUNICATION

Truthful, clear communication during an outbreak or epidemic is critical to successfully conveying public health messages, implementing infection control measures, and engaging communities in the entire process of response. There are a variety of ways to convey messages to communities, including radio, television, community meetings, and social media. Each of these has benefits and limitations, and the characteristics of the community should be taken into account when choosing a communication method (WHO, 2012). The success of response and research activities is contingent on community understanding of diseases, their mode of transmission and spread, public health control strategies, the availability of a proven therapy, and the research process. Experiences from previous

___________________

8 Personal communication with Christopher McShane, Janssen Research & Development, LLC. COMAHS (Sierra Leone College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences) and MoHS (Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation). 2015. Ebola flipcharts: A community Ebola marklate study in Sierra Leone.

outbreaks have shown that a paternalistic view of how to affect human behavior through provision of one-size-fits-all messaging is insufficient and ineffective, as “community understanding of diseases and their spread is complex, context dependent, and culturally mediated” (WHO, 2009, p. 6; see also Sugg, 2016). Communication programs targeted at low- and middle-income countries by Western, expert-led campaigns run the risk of casting individuals in those countries in the role of passive objects, rather than agents of their own change. The Ebola communication response ultimately went well beyond “messaging.” Community dialogue, listening, and discussion—both face-to-face and through the media—were essential to bringing about change. “Communication is not something that happens to people,” observed Bernhard Schwartlander of the World Health Organization. “You need to engage those that you want to reach in such a way that those communities take up the responsibility for communicating themselves” (Sugg, 2016, p. 16).

During the Ebola outbreak, early outreach and messaging efforts were confusing and counterproductive; the “public was initially inundated with complex information about Ebola transmission” (Bedrosian et al., 2016). A report by the All Party Parliamentary Group for Africa states that in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone in 2014, communication initially amplified the terrifying impact of the disease: “Initial communication campaigns focused on raising awareness about Ebola, informing people of the signs, symptoms, and how to seek help, but there was little effort to build the capacity of local journalists to spread accurate information and raise awareness” (Polygei, 2016, p. 38). Many messaging attempts by response workers were not informed by communication and behavioral sciences and did little to address underlying beliefs, including a pervasive idea that Ebola was not real. Many community members were convinced of this; in fact one small qualitative study in Sierra Leone revealed that nearly all of the participants did not think that Ebola was real (Yamanis et al., 2016). Furthermore, most feared that calling the national hotline for someone suspected of having Ebola would result in the person’s death, and many said they would self-medicate if they developed a fever (Yamanis et al., 2016). Initial communications of the governments and international agencies included dramatic and fear-inducing messages such as “Ebola kills,” “There is no cure for Ebola,” and “Don’t touch,” which stigmatized those with the disease and deterred people from seeking care (Polygei, 2016). There were also reports that research messages may have occasionally interfered with other public health or response goals. For example, the Liberian Civil Society Organizations’ Ebola Response Task Force expressed some concerns about the rollout of the PREVAIL vaccine trial in February 2015. The task force stated that the PREVAIL trial team, in spite of its efforts to engage the community in discussion, did not do an adequate job educating the public about

the difference between the Ebola experimental vaccine and the standard childhood vaccination program and, consequently, was partly responsible for the low turnout of children to receive the standard vaccines to prevent childhood communicable disease (CSO-Ebola, 2015).

These missteps, however small, exacerbated community mistrust of responders as well as researchers and hampered efforts to treat patients or to recruit volunteers for clinical trials (Sugg, 2016). However, by the end of 2014, the increasing emphasis on communication interventions had contributed to a shift in public attitudes and understanding about Ebola. Public health professionals began empowering community organizers with insights and practical advice. Health professionals started to engage with local leaders and communities more systematically, listening to their concerns and ideas. They also began training local journalists and media hosts to provide accurate information. The CDC reported that “recognizing the need to simplify and coordinate messaging, CDC partners worked with the Sierra Leone National Ebola Response Centre to launch the Ebola Big Idea of the Week campaign. Approximately 80 radio, television, and print journalists from across the country were trained by experts on critical communication topics from CDC and other partner organizations. . . . In Guinea, coordinated communication strategies addressed cultural differences and focused on identifying trusted local spokespersons and Ebola survivors who could relate to diverse communities. . . . Central to the response was collaboration with these partners to deliver coordinated messages and avoid duplication of effort while respecting individuals and communities” (Bedrosian et al., 2016, p. 70).

In another example of effective communication, the Liberia DeySay project (“DeySay” is a reference to how people speak about rumors in Liberian English) attempted to identify and dispel rumors in real time (Iacucci, 2015). Hundreds of health workers, NGO staff, and volunteers on the ground were given a phone number and asked to send a text message when they became aware of a rumor circulating. A central coordination hub collected and analyzed the messages and sent information to local media partners, who could use their influence to help to dispel the rumors. DeySay also produced a weekly newsletter that highlighted the most critical rumors in circulation and advised media with insights on information gaps and health reporting (Iacucci, 2015).

Effective communication between different stakeholders and communities is critical to the epidemic response, and the success of research efforts is contingent upon successful communication within the broader epidemic response. Social and behavior change communication encompasses a range of approaches and tools, including interpersonal communication, work with mass media and other information and communication technologies, and social mobilization. Communication and social mobilization are dis-

tinctive skill sets and require the participation of experienced experts. Early in an outbreak, all stakeholders should collaborate closely and harmonize the messages going to the public—for example, there should be no inconsistencies in the information or advice given to the public by the public health, clinical care, and research messages.

Conclusion 6-4 Communication as part of the epidemic response is vitally important to the success of health care and public health measures as well as of clinical research. Increased funding for training and research into the science of culturally relevant communication to facilitate research and response during epidemics would lay the groundwork for better health and public health messaging to the general public both between and during epidemic emergencies.

SUMMARY

Community engagement is a lengthy process, and outbreak response and clinical trial teams not only need to reach the community and provide information during an epidemic, but also must deal with preexisting knowledge and beliefs, whatever their origins or basis. A research team may bring new information and insights, but it never starts from zero when entering a new community during an epidemic. There are existing perceptions and beliefs that will influence how a community views the research and the researcher; in these contexts, history is not negligible. To gain community trust and to conduct valid, high-quality research, researchers must establish relationships with members and leaders throughout a community; this is even more challenging to do during an epidemic, when the fear of disease and death, rumors, and restrictions on movement interfere with the normal means of communication. However, to use resources wisely, respond most rapidly, and contain the epidemic quickly, there must be community engagement and a community-led response.

Recommendation 6a

Prioritize community engagement in research and response—Epidemic International and national research institutions, public health agencies, and humanitarian organizations responding to an outbreak should engage communities in the research and response by

- Identifying social science experts in community engagement and communications to lead their efforts to effectively engage and connect with communities affected by the epidemic.

- Consulting with key community representatives from the outset of an outbreak to identify a range of local leaders who can participate in planning research and response efforts, help to map community

-

assets, articulate how to infuse cultural and historical context into presentations, and identify gaps and risks in developing public health measures and designing research protocols. Consultations should be continued throughout the implementation phase by relevant actors to provide information as the outbreak evolves, provide feedback about progress and results, and inform and recommend changes to strategies based on feedback from the community.

- Coordinating within and across sectors, with national authorities, and with each other to ensure alignment of social mobilization and communication activities with the overall response and research strategies, and that there is sufficient support and training to local leaders and organizations to engage communities in research and response.

As discussed in this chapter, successful community engagement and effective communication during a public health emergency or epidemic depend on the context, the specific community, and the particular goals of engagement and communication. This would no doubt be easier and less fraught with problems of trust if, during inter-epidemic periods, stakeholders invested more time, training, research, and funding into developing frameworks and strategies for community engagement and communication about health and public health that could be translated to the circumstances of an epidemic. Certainly in West Africa, the post-outbreak period is an opportunity to build on the successful efforts from later in the epidemic to connect with and engage communities in the research and response. This would be an ideal time to learn more about what did and did not work and about how to improve on the communication of health, public health, and health research messages. While there are many ongoing health concerns to address and there is a need to build better capacity and expertise, it is also an excellent time to continue to engage in dialogue about Ebola and, in particular, to share what was learned in each country from the clinical research that was done and how this information could be productively used in a future outbreak. Partnerships established during the outbreak can be leveraged to engage in this work and to solicit support for the dissemination of Ebola information and to develop a network between the newly established and strengthened public health units and the media and communication channels used by and in the communities.

Recommendation 6b

Fund training and research into community engagement and communication for research and response—Inter-epidemic

The World Health Organization, international research institutions, governments, public health agencies, and humanitarian organizations

should actively collaborate together to fund training and research for developing frameworks, networks, strategies, and action plans for community engagement and communication on public health and research that could inform and be mobilized during an epidemic.

REFERENCES

Abramowitz, S. A., K. E. McLean, S. L. McKune, K. L. Bardosh, M. Fallah, J. Monger, K. Tehoungue, and P. A. Omidian. 2015. Community-centered responses to Ebola in urban Liberia: The view from below. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 9(4):e0003706.

Act Alliance. 2014. Appeal: Sierra Leone—Ebola sensitization and prevention in Sierra Leone—SLE141. September 24, Geneva, Switzerland. http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SLE141_SLeone_Ebola.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

Afolabi, M. O., N. McGrath, U. D’Alessandro, B. Kampmann, E. B. Imoukhuede, R. M. Ravinetto, N. Alexander, H. J. Larson, D. Chandramohan, and K. Bojang. 2015. A multimedia consent tool for research participants in the Gambia: A randomized controlled trial. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 93:320–328A.

Ahmed, S. M., and A.-G. S. Palermo. 2010. Community engagement in research: Frameworks for education and peer review. American Journal of Public Health 100(8):1380–1387.

Bedrosian, S., C. Young, L. Smith, J. D. Cox, C. Manning, L. Pechta, J. L. Telfer, M. GainesMcCollom, K. Harben, W. Holmes, K. M. Lubell, J. H. McQuiston, K. Nordlund, J. O’Connor, B. S. Reynolds, J. A. Schindelar, G. Shelley, and K. L. Daniel. 2016. Lessons of risk communication and health promotion—West Africa and United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65(Suppl 3):68–74.

Berndtson, K., T. Daid, C. S. Tracy, A. Bhan, E. R. M. Cohen, R. E. G. Upshur, J. A. Singh, A. S. Daar, J. V. Lavery, and P. A. Singer. 2007. Grand challenges in global health: Ethical, social, and cultural issues based on key informant perspectives. PLoS Medicine 4(9):e268.

Botbol-Baum, M., M. Brodin, A. Desclaux, F. Hirsch, C. Longuet, A.-M. Moulin, and B. Taverne. 2015. From HIV to Ebola: Ethical reflections on health research in the global south and recommendations from Inserm and IRD. Inserm Ethics Committee and IRD CCDE.

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2015. Launch of STRIVE Ebola vaccine trial. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2015/a0413-strive.html (accessed January 25, 2017).

CDC. 2016. CDC’s response to the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic—West Africa and United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65(3) [entire issue]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/su/pdfs/su6503.pdf (accessed January 30, 2017).

Chaisson, L. H., N. E. Kass, B. Chengeta, U. Mathebula, and T. Samandari. 2011. Repeated assessments of informed consent comprehension among HIV-infected participants of a three-year clinical trial in Botswana. PLoS ONE 6(10):e22696.

Chang, M. S., E. M. Christophel, D. Gopinath, and R. M. Abdur. 2011. Challenges and future perspective for dengue vector control in the Western Pacific region. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal 2(2):9–16.

CIOMS (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences). 2016. International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects. http://www.cioms.ch/ethical-guidelines-2016 (accessed January 20, 2017).

Connolly, M. A., M. Gayer, M. J. Ryan, P. Salama, P. Spiegel, and D. L. Heymann. 2004. Communicable diseases in complex emergencies: Impact and challenges. The Lancet 364(9449):1974–1983.

CSO–Ebola (Civil Society Ebola Response Task Force). 2015. Liberia Civil Society Organizations Ebola Response Task Force: Policy brief. February. http://lmcliberia.org/sites/default/files/Policy%20Brief%20on%20Vaccine%20Trials%20%2B%20Financial%20Tracking%20%20(final).pdf (accessed January 25, 2016).

DELWP (Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning). 2013. Types of engagement. http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/effective-engagement/developing-an-engagement-plan/types-of-engagement (accessed January 25, 2017).

Dhillon, R. S., and J. D. Kelly. 2015. Community trust and the Ebola endgame. New England Journal of Medicine 373(9):787–789.

Diallo, D. A., O. K. Doumbo, C. V. Plowe, T. E. Wellems, E. J. Emanuel, and S. A. Hurst. 2005. Community permission for medical research in developing countries. Clinical Infectious Diseases 41(2):255–259.

Doe-Anderson, J., B. Baseler, P. Driscoll, M. Johnson, J. Lysander, L. McNay, W. S. Njoh, M. Smolskis, L. Wehrlen, and J. Zuckerman. 2016. Beating the odds: Successful establishment of a Phase II/III clinical research trial in resource-poor Liberia during the largest-ever Ebola outbreak. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 4:68–73.

Ebola Response Anthropology Platform. 2017. About the network. http://www.ebola-anthropology.net/about-the-network (accessed February 20, 2017).

Enria, L., S. Lees, E. Smout, T. Mooney, A. F. Tengbeh, B. Leigh, B. Greenwood, D. Watson-Jones, and H. Larson. 2016. Power, fairness and trust: Understanding and engaging with vaccine trial participants and communities in the setting up the EBOVAC–Salone vaccine trial in Sierra Leone. BMC Public Health 16:1140.

Faruque, A., A. Eusof, A. Q. Islam, S. Akbar, and M. Sarkar. 1985. Community participation in a diarrhoeal outbreak: A case study. Tropical and Geographic Medicine 37(3):216–222.

Fast, L. 2015. On the importance of human connection: Fear, Ebola and security. https://humanitarianhealthethics.net/2015/03/27/on-the-importance-of-human-connection-fear-ebola-and-security (accessed January 25, 2017).

Feuer, A. 2014. The Ebola conspiracy theories. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/19/sunday-review/the-ebola-conspiracy-theories.html?_r=2 (accessed February 20, 2017).

Folayan, M. O., K. Peterson, and F. Kombe. 2015. Ethics, emergencies and Ebola clinical trials: The role of governments and communities in offshored research. The Pan African Medical Journal 22(Suppl 1):10.

George, A. S., V. Mehra, K. Scott, and V. Sriram. 2015. Community participation in health systems research: A systematic review assessing the state of research, the nature of interventions involved and the features of engagement with communities. PLoS ONE 10(10):e0141091.

Global Communities. 2015. Assisting Liberians with Education to Reduce Transmission (ALERT)—Quarterly report. April 30. Silver Spring, MD: Global Communities. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00KN8V.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2013. Guidance for institutional review boards, clinical investigators, and sponsors: Exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM249673.pdf (accessed February 20, 2017).

HHS. 2016. Informed consent information sheet: Draft guidance. July 2014. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.fda.gov/Regulatory-Information/Guidances/ucm404975.htm (accessed January 25, 2017).

Iaccino, L. 2014. Ebola “caused by Red Cross” and other conspiracy theories. http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/ebola-caused-by-red-cross-other-conspiracy-theories-1469896 (accessed February 20, 2017).

Iacucci, A. A. 2015. Combatting rumors about Ebola: SMS done right. https://medium.com/local-voices-global-change/combatting-rumors-about-ebola-sms-done-right-da1da1b222e8#.1ui1vbs1x (accessed January 25, 2017).

Jhanwar, V. G., and R. J. Bishnoi. 2010. Comprehensibility of translated informed consent documents used in clinical research in psychiatry. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 32(1):7–12.

Kickbusch, I., and K. S. Reddy. 2015. Community matters—Why outbreak responses need to integrate health promotion. Global Health Promotion 23(1):75–78.

King, N. 2014. Empathetic and efficient PPE. https://challenges.openideo.com/challenge/fighting-ebola/impact/empathetic-and-efficient-ppe (accessed January 25, 2017).

Kobayashi, M., K. D. Beer, A. Bjork, K. Chatham-Stephens, C. C. Cherry, S. Arzoaquoi, W. Frank, O. Kumeh, J. Sieka, A. Yeiah, J. E. Painter, J. S. Yoder, B. Flannery, F. Mahoney, and T. G. Nyenswah. 2014. Community knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding Ebola virus disease—Five counties, Liberia, September–October, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64(26):714–718.

Laverack, G., and E. Manoncourt. 2015. Key experiences of community engagement and social mobilization in the Ebola response. Global Health Promotion 23(1):79–82.

Logan, G., N. M. Vora, T. G. Nyensuah, A. Gasasira, J. Mott, H. Walke, F. Mahoney, R. Luce, and B. Flannery. 2014. Establishment of a community care center for isolation and management of Ebola patients—Bomi County, Liberia, October 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 63(44):1010–1012.

Marais, F., M. Minkler, N. Gibson, B. Mwau, S. Mehtar, F. Ogunsola, S. Banya, and J. Corburn. 2016. A community-engaged infection prevention and control approach to Ebola. Health Promotion International 31(2):440–449.

McMillan, J., and C. Conlon. 2004. The ethics of research related to health care in developing countries. Journal of Medical Ethics 30(2):204–206.

Mohle-Boetani, J. C., M. Stapleton, R. Finger, N. H. Bean, J. Poundstone, P. A. Blake, and P. M. Griffin. 1995. Communitywide shigellosis: Control of an outbreak and risk factors in child day-care centers. American Journal of Public Health 85(6):812–816.

Mukpo, A. 2015. Surviving Ebola: Public perceptions of governance and the outbreak response in Liberia. London: International Alert. http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Liberia_SurvivingEbola_EN_2015.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

NBAC (National Bioethics Advisory Commission). 2001. Ethical and policy issues in international research: Clinical trials in developing countries. Volume I: Report and recommendations of the National Bioethics Advisory Commission. Bethesda, MD: National Bioethics Advisory Commission. https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/nbac/clinical/Vol1.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

NIAID (National Institue of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). 2015. Liberia–U.S. clinical research partnership opens trial to test Ebola treatments. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/liberia-us-clinical-research-partnership-opens-trial-test-ebola-treatments (accessed January 25, 2017).

Nuffield Council on Bioethics. 2002. The ethics of research related to healthcare in developing countries. http://nuffieldbioethics.org/report/research-developing-countries-2/chapter-downloads (accessed January 20, 2017).

Nyika, A., R. Chilengi, D. Ishengoma, S. Mtenga, M. A. Thera, M. S. Sissoko, J. Lusingu, A. B. Tiono, O. Doumbo, S. B. Sirima, M. Lemnge, and W. L. Kilama. 2010. Engaging diverse communities participating in clinical trials: Case examples from across Africa. Malaria Journal 9:86–86.

Okonta, P. I. 2014. Ethics of clinical trials in Nigeria. Nigerian Medical Journal 55(3):188–194.

Onishi, N., and S. Fink. 2015. Vaccines face same mistrust that fed Ebola. New York Times, March 13. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/14/world/africa/ebola-vaccine-researchers-fight-to-overcome-public-skepticism-in-west-africa.html?_r=0 (accessed January 30, 2017).

Polygei. 2016. Lessons from Ebola affected communities: Being prepared for future health crises. Cambridge, UK: Polgeia. http://www.royalafricansociety.org/sites/default/files/reports/AAPPG_report_3.10_sngls_web.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

Samandari, T., T. B. Agizew, S. Nyirenda, Z. Tedla, T. Sibanda, N. Shang, B. Mosimaneotsile, O. I. Motsamai, L. Bozeman, M. K. Davis, E. A. Talbot, T. L. Moeti, H. J. Moffat, P. H. Kilmarx, K. G. Castro, and C. D. Wells. 2011. 6-month versus 36-month isoniazid preventive treatment for tuberculosis in adults with HIV infection in Botswana: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet 377(9777):1588–1598.

Schulz-Baldes, A., E. Vayena, and N. Biller-Andorno. 2007. Sharing benefits in international health research. Research-capacity building as an example of an indirect collective benefit. EMBO Reports 8(1):8–13.

Sendolo, J. 2016. Dr. Golakai decries discrepancies in Ebola research. Liberian Daily Observer, August 18. http://www.liberianobserver.com/news/dr-golakai-decries-discrepancies-ebola-research (accessed January 25, 2017).

Sugg, C. 2016. Coming of age: Communication’s role in powering global health. Policy Briefing No. 18. London, UK: BBC Media Action. http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/publications-and-resources/policy/briefings/role-of-communication-in-global-health (accessed January 25, 2017).

Wellcome Trust. 2011. Community engagement—Under the microscope. June 12–15, 2011. London, UK: Wellcome Trust. https://wellcome.ac.uk/sites/default/files/wtvm054326_0. pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2009. Social mobilization in public health emergencies: Preparedness, readiness, and response: Report of an informal consultation. Held on December 10–11, 2009. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70444/1/WHO_HSE_GAR_BDP_2010.1_eng.pdf (accessed January 25, 2017).

WHO. 2012. Communication for behavioural impact (COMBI): A toolkit for behavioural and social communication in outbreak response. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75170/1/WHO_HSE_GCR_2012.13_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed January 25, 2017).

Widdowson, M., S. Schrag, R. Carter, W. Carr, J. Legardy-Williams, L. Gibson, D. R. Lisk, M. I. Jalloh, D. A. Bash-Taqi, S. A. Sheku Kargbo, A. Idriss, G. F. Deen, J. B.W. Russell, W. McDonald, A. P. Albert, M. Basket, A. Callis, V. M. Carter, K. R. Clifton Ogunsanya, J. Gee, R. Pinner, B. E Mahon, S. T. Goldstein, J. F. Seward, M. Samai, and A. Schuchat. 2016. Implementing an Ebola vaccine study—Sierra Leone. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65(Suppl 3):98–106.

Wilson, B., J. B. Cooper, J. Lysander, K. Bility, J. D. Anderson, J. Endee, H. Kiawu, L. Doepel, and E. Higgs. 2016 (unpublished). Engaging communities in clinical research during a public health emergency: An ethical norm. Funded by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Yamanis, T., E. Nolan, and S. Shepler. 2016. Fears and misperceptions of the Ebola response system during the 2014–2015 outbreak in Sierra Leone. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 10(10):e0005077.

Yates, D. A. 2015. PREVAIL admits neglect in promoting vaccine trials. Liberian Daily Observer, February 5. http://liberianobserver.com/columns-health/prevail-admits-neglect-promoting-vaccine-trials (accessed January 25, 2017).