2

Overview

The workshop opened with two presentations designed to serve as background for the subsequent sessions. Susan Havercamp, associate professor of psychiatry and psychology at The Ohio State University’s Nisonger Center, and Silvia Yee, senior staff attorney at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund,1 summarized a paper commissioned by the two roundtables for this workshop. Havercamp presented a framing of disability, a demographic analysis of people with disabilities, and the socioeconomic and health-specific barriers experienced by people with disabilities at the intersection of race and disability. Yee provided a review of federal disability laws, and an overview of various supports and services for people with disabilities.

Eva Marie Stahl, director of the Community Catalyst Children’s Health Project at Community Catalyst,2 and Rosa Palacios, consumer engagement specialist with the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation at Community Catalyst, then discussed the intersection of health equity, disability, and health literacy; described some of their organization’s efforts to advance health literacy among those with disabilities; and presented some evidence-based strategies for self-management that are working in communities today. An open discussion, moderated by Antonia Villarruel, professor and the Margaret Bond Simon Dean of Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania, followed the presentations.

___________________

1 See http://dredf.org (accessed October 10, 2017).

2 See http://www.communitycatalyst.org (accessed October 10, 2017).

HEALTH DISPARITIES AND EQUITY AT THE INTERSECTIONS OF DISABILITY, RACE, AND ETHNICITY3

Anyone can become disabled at any time during his or her life span, said Havercamp, and today, about 22 percent of adults and 14 percent of children in the United States are living with at least one disability, which includes any mental or physical trait that limits functional capacity. In fact, disabilities are so common that the World Health Organization (WHO) has concluded that disability is a natural feature of the human condition. What surprises many Americans is that more than 97 percent of those with disabilities live in the community, not in nursing homes, hospitals, or other institutions.

The nature of disability depends on perspective, said Havercamp. The traditional medical model views disability as a characteristic or attribute of the individual, where the disability is caused by disease, trauma, or another health condition and requires an intervention to correct or compensate for the problem. In contrast, the social model views disability as a socially created problem, not a personal attribute, resulting from an unaccommodating and inflexible social or physical environment. In this model, management of the problem requires social action, and it becomes the responsibility of society at large to modify the environment in a manner that allows those with disabilities to participate fully in all activities. WHO merged these two models when it created the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO, 2001), which explicitly recognizes that external factors—the physical environment, social structures, government policies, and societal attitudes—contribute to or mitigate disability. In this hybrid view, disability is an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions.

According to Havercamp, the passage of critical laws and the provision of appropriate services and supports are direct measures intended to give people with disabilities the tools they need to survive in the community. These measures, however, will not in themselves transform a system that fails to recognize the presence of inequality and discrimination in the documented health disparities and unequal access experienced by people with disabilities. “We cannot move forward into a demographic analysis of how race and ethnicity intersect with disability or a discussion of supports and legal protections for people with disabilities until we recognize how deeply every socioeconomic characteristic associated with disability is

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Susan Havercamp, associate professor of psychiatry and psychology at The Ohio State University’s Nisonger Center, and Silvia Yee, senior staff attorney at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

mistakenly assumed to be a natural and direct consequence of disability,” said Havercamp.

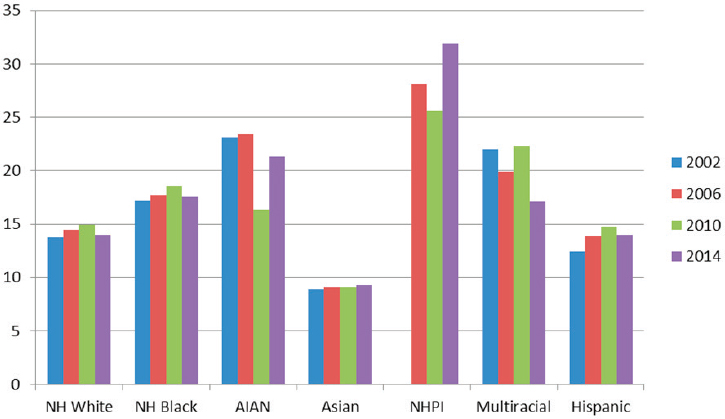

Data on disability status come from several national population-based sources, including the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which Havercamp said provides the most detail about disability in the United States (Altman and Bernstein, 2008). Analyses of the distribution of disability across race and ethnicity are limited in number, she added, but these analyses reveal a consistent pattern of higher prevalence of physical disability among non-Hispanic blacks, American Indian and Alaska Natives (AIANs), Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders (NHPIs), and multiracial individuals (see Figure 2-1) when compared to whites. Few Asian NHIS respondents reported having a disability, and the prevalence of physical disability among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white respondents is similar.

Havercamp said that while public health and policy experts agree on the need to assess health disparities and health care inequities experienced by historically disadvantaged groups and subpopulations of interest, these assessments often fail to consider the significance of collecting data on members of historically disadvantaged groups with disabilities. “All health equity research must include disability in the form of disability-related

NOTE: AIAN = American Indian or Alaska Native; NH = non-Hispanic; NHPI = Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: Havercamp and Yee presentation, June 14, 2016.

indicators to ensure comprehensive data for all people across racial and ethnic groups,”4 said Havercamp, who noted that disability is now considered a demographic characteristic similar to age, race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation, rather than a negative health outcome (see, for example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the U.S. Department of Labor). In the commissioned paper accompanying this Proceedings of a Workshop, she and her co-authors recommend that all researchers who investigate health equity, health disparities, or social determinants of health of people of color and other historically underrepresented groups and who seek to collect population data should include at a minimum the six markers listed in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) Implementation Guidelines on Minimum Data Collection Standards for Disability:

- Are you deaf or do you have serious difficulty hearing?

- Are you blind or do you have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses?

- Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, do you have serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions? (5 years old or older)

- Do you have serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs? (5 years old or older)

- Do you have difficulty dressing or bathing? (5 years old or older)

- Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, do you have difficulty doing errands alone such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping? (15 years old or older)

Collecting such data, she added, will be helpful in understanding relationships between health and well-being.

Adults with disabilities, explained Havercamp, are far less likely to graduate from high school with a diploma and are largely absent from post-secondary education.5 Rates of poverty and unemployment,6 as well as food insecurity (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2013), are higher for people with disabilities, and individuals with disabilities are twice as likely to be a victim of crime (Harrell, 2015). People with disabilities are also twice as likely to report transportation as a major barrier in their lives (Durant, 2003). Socially, children and adults with disabilities report feeling socially isolated and that discrimination is a major barrier in their lives. People

___________________

4 The two major sets of items used as indicators are the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Implementation Guidance Questions and the Washington Group Short Set.

5 See http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/tables/ACGR_RE_and_characteristics_2013-14.asp (accessed October 10, 2017).

6 See http://disabilitycompendium.org/statistics/poverty (accessed October 10, 2017).

with disabilities are equally likely to be uninsured and more likely to be covered by publicly funded health insurance. Despite comparable rates of health insurance coverage, adults with disabilities have much poorer health outcomes compared to adults without disabilities and are two to three times more likely to report not having access to needed health care in the past year because of cost.

“People with disabilities are not destined for a life of poor health status by virtue of their disability,” said Havercamp. “Rather, it is the lack of institutional support for this underserved population that contributes to the poor health outcomes, a phenomenon seen among all historically underserved populations.” She noted that, just as stereotypes about certain racial and ethnic groups by health care providers can negatively affect health outcomes and contribute to health disparities, negative attitudes toward and assumptions about disabilities have an adverse impact on the health and the quality of health care for people with disabilities.

Health care providers and public health workers make three fundamental assumptions that limit health and health care for people with disabilities, said Havercamp. The first assumption is that people with disabilities differ in significant, meaningful, and somewhat undefined ways from other people. The second assumption, which limits the quality of care, is that people with disabilities have a lower level of cognitive ability, independence, and interest in improving and maintaining current function. The third assumption, that the quality of life for a disabled person is severely compromised, limits the type, scope, and aggressiveness of considered treatment options.

Taken together, these assumptions may profoundly affect health care provider communication, health literacy, and ultimately the health of patients with disabilities.

Havercamp said that thought leaders both in the National Academy of Medicine and in health care in general recommend that “we as a society improve knowledge, skills, and attitudes of health care providers to improve the health and health care of people with disabilities.” Currently, she noted, there is no requirement to include disability in the training of future physicians or other health care providers in the United States. Similarly, most public health and human service training programs do not include a curriculum on disabilities or methods for including them in core public health efforts. “If accreditation standards were expanded to address the health needs of people with disabilities—roughly 20 percent of the population—we could begin to improve the health of this underserved population,” said Havercamp. “The fact that disability is largely absent from public health training and practice leaves public health unprepared to address the health needs of this vulnerable population.” What is particularly detrimental, she added, is how public health issues are prioritized and researched.

One impediment to providing quality health care to those with disabilities is the use of the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) measure to objectively quantify the impact of disease, health behaviors, and interventions as a means of setting priorities and allocating public health resources, said Havercamp. DALYs, she explained, estimate disease burden by combining estimates of premature mortality and estimates of years of productive life lost to disability, but this measure is problematic for two reasons: (1) this instrument is based on the premise that a disabled person’s life is less valuable and thus less cost-effective than the life of an able-bodied person, and (2) disability weights are established by comparing the usefulness and quality of life for people with different disabilities, which grossly underestimates the abilities and quality of life for people with disabilities.

Instead of DALYs, Havercamp and her co-authors recommend that journals, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) use health-adjusted life years in research.

Another issue regarding the provision of health care to those with disabilities is their routine exclusion from clinical trials and other public health research in the interest of recruiting a homogeneous sample to maximize the odds of measuring an effect. “However, excluding people with comorbidities from this research leads to creation of an evidence base that is not representative of the general population,” said Havercamp. She noted that the NIH Revitalization Act ensured the inclusion of women and diverse racial groups when it required the reporting of racial and gender makeup of NIH-funded clinical trials. “Similar reporting requirements for disability would take a step toward equity for this population,” she said.

The Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine can be credited, said Havercamp, with drawing attention to the importance of adapting health information to the everyday lives of people and their communities. Doing so requires understanding the cultural context of the family, which must include disability. However, she said, there is a paucity of research and intervention literature that specifically examines health literacy within the context of people with disabilities, and nothing that she knows of responds to the racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity among people with disabilities. “People with disabilities must be included in health literacy research efforts to address the many cultural and linguistic differences that impact health in this population,” said Havercamp.

Concluding her portion of the presentation, Havercamp said that people with disabilities and people from underserved racial and ethnic groups both experience barriers to health care as well as disparities in other social determinants of health. These barriers and disparities could well be exac-

erbated for people who belong to both of these marginalized populations, and while research on health and health care disparities at the intersection of disability and race and ethnicity is limited, the available evidence suggests that disparities may indeed be compounded. “Analyses of data from multiple population-based sources have found that adults with disabilities in underserved racial and ethnic groups are more likely to report fair or poor health and delayed and unmet health care needs, even when controlling for socioeconomic status and health insurance,” said Havercamp (Wolf et al., 2008). She noted that children with disabilities in underserved racial and ethnic groups are less likely to have health insurance or access to the usual sources of care, and they are more likely to have been unable to get needed medical care and to have been hospitalized or used the emergency room. “More research is needed to understand specifically how health care barriers faced by people with disabilities may be compounded by race and ethnicity,” she said.

Turning to the subject of federal laws and existing supports, as well as services for people with disabilities, Silvia Yee said that these are seen as important tools for meeting the health needs of people with disabilities and breaking down the barriers that can prevent them from receiving appropriate care. However, while these two tools do enable some successes, Yee said they fall considerably short of ensuring that people with disabilities receive adequate and equitable treatment of their health needs.

There are many federal laws dealing with disability. The first, dating back to 1798, established a federal network of hospitals for the relief of sick and disabled seamen. Early federal laws applied to specific situations and diagnostic categories, but the trend in the second half of the 20th century was for federal law to be more holistic. The following are examples of federal law relating to people with disabilities:

- The Social Security Act of 1950 created a public assistance program for people who are “totally and permanently disabled.”

- The 1963 Developmental Disabilities Act established university-affiliated facilities to train professionals to work with people with developmental disabilities.

- The creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 expanded how disabilities were understood in federal law.

- The 1970 Developmental Disabilities Services and Facilities Construction Amendments Act had the effect of building better institutions and facilities for people with developmental disabilities.

Yee noted that one law in particular, the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 1975, represented a leap in acknowledging

that people with disabilities have a set of rights that often are not recognized in their treatment and in institutions: it created a state protection and advocacy system to secure the rights of individuals with developmental disabilities. This law represented a turning point, said Yee, because it recognized that it is not enough to simply bestow rights on those with disabilities because, as a group, they may not necessarily know their rights or how they would enforce them. This law led to the creation of a federally funded protection and advocacy agency in every U.S. state to provide advice, advocacy, legal assistance, and representation to those with disabilities. While these agencies focused initially on people with developmental disabilities, they have evolved to serve a wide range of people with disabilities.

The legal framework regarding disability has also evolved to support deinstitutionalization and rebalancing. Deinstitutionalization is critical to the disability community, said Yee. “I do not think there is any other community that stands so at risk of being told, ‘If you want to keep your life, you need to live it in an institution away from your family, away from your community, away from the life that you lead,’” said Yee. The 1987 Nursing Home Reform Act, for example, required states to conduct preadmission screening of individuals with disabilities prior to their admission to a nursing facility to determine if they actually needed nursing facility–level care. If an individual did not, but did require specialized services, the state was to provide or arrange for such services in an appropriate setting.

Yee noted that as the law has developed, Medicaid is the only public source of funds for long-term care, yet this is poorly understood by the public. Too many Americans, she said, believe that Medicare will take care of them if they become disabled, but Medicare will not support long-term chronic care needs. Medicaid, she explained, has always required that states pay for institutional care if an individual needs long-term care and qualifies for institutional care. However, states do not have to provide, under law, a home and community-based equivalent of institutional care, creating what Yee called an institutional bias in the law. “Many people in the disability community have been fighting for years to overcome that, to try to rebalance how money is spent in the Medicaid system,” said Yee, who added that the law is slowly evolving toward that type of rebalancing.

Federal oversight, monitoring, and implementation, versus federal deferral to state flexibility, has increased with the advent of civil rights laws, such as the 1973 Rehabilitation Act and the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). These laws recognize people with disabilities as individuals who have the right to be free of discrimination and barriers, said Yee, and as with all civil rights, they set a floor of rights for the entire country. It was not the case, she explained, that no state had any kind of disability rights, but there was a patchwork, just as there used to be for racial and ethnic groups prior to the passage of landmark civil rights laws in the 1960s and

1970s. Today, when federal law says the state must meet some particular need, the states have latitude as to how to meet that need within certain parameters.

One of the most important advances for those with disabilities came with the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Olmstead v. L.C. in 1999. The ruling recognized that people with disabilities have the right to be in a community and that it is against the law to isolate and segregate people with disabilities when they want to live in the community. The one caveat to this ruling, said Yee, is that it has been far more effective in getting states to stop doing something rather than requiring them to proactively take positive action.

Addressing the limitations of the many laws relating to disability, Yee said that they do not remedy the fragmented delivery of services and supports for those with disabilities. In particular, she said, there is a sharp division between medical care and long-term services and supports. This division is particularly experienced by individuals who are dually eligible for Medicare services, because of disability or age, and for Medicaid services, because of low income. Medicare provides medical services, while Medicaid provides long-term services and supports. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) created a new office at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to help coordinate policies and procedural barriers between these two programs (the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office).

Another limitation is that civil rights laws are not self-executing, by which she meant that they rely heavily on individual complaints and lawsuits. “That can be very much an issue for people with disabilities who already lead complex lives when it comes to maintaining their health and place in their community,” said Yee. “If you are facing a health crisis, the last thing you are thinking of is suing your doctor, and because there is so much inaccessibility among health care providers, if you sue and cut off your relationship with one physician, what are the chances you are going to find another one who has the knowledge you need and who is accessible?”

The administrative complexity of the U.S. health care system also factors into both the difficulty of enforcing nondiscrimination and in providing long-term services and supports, said Yee. She added that existing nondiscrimination laws are poor tools for forcing systemic change in such critical areas as provider training, interagency coordination, and intersectional data collection.

Accessing long-term services and supports is critical for the well-being of people with chronic disabilities, as is care coordination among physical and mental health care providers and between medical care and the providers of long-term services and supports, said Yee. Partnerships between community-based organizations addressing aging or disability on the one

hand and primary managed care organizations and providers on the other are important avenues for providing long-term services and supports, particularly as managed care organizations take over the responsibility of delivering Medicaid services. The problem, said Yee, is that these two groups are not accustomed to working with one another, and there are barriers that limit potential partnerships. One area in which this can be seen is in providing community-based housing for individuals with disabilities, something that Medicaid cannot fund. Yee noted that managed care organizations are just starting to innovate here because they recognize that it is hard to be healthy without a stable place to live, particularly for those with chronic conditions and disabilities. She also remarked on the slow recognition of the need for physical and programmatic accessibility7 in managed care and provider network adequacy, a topic that subsequent speakers would address.

Yee concluded her talk by listing the following key recommendations in the commissioned paper accompanying this Proceedings of a Workshop:

- Improve data collection by mandating the use of the six HHS disability questions in relevant population surveys and electronic health records (EHRs). These data should be used to monitor and report health-related differences between groups according to disability, race, ethnicity, and other personal characteristics.

- Conduct research, including an intersectionality report from CMS, looking specifically at this population of individuals who may be facing compound disparities and funding for independent investigators to examine the intersection between disability, race, and ethnicity.

- Systematically include people with disabilities in health equity, health literacy, and clinical trials research efforts, and address the racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity among people with disabilities.

- Establish a core training requirement on cultural competence in disability, race, and ethnicity in health care, public health, and human service training programs.

- Sufficiently independent state or federal entities should consistently monitor compliance with disability accessibility laws.

- Create practical methods to implement, monitor, and enforce the intent of the disability accommodation language in Medicaid man

___________________

7 Programmatic accessibility means that individuals with disabilities must be able to access the same information as nondisabled individuals.

-

aged care regulations, Medicaid 1115 waivers,8 and various dual-eligible demonstration contracts. Accessibility requirements must be substantively incorporated within accreditation and funding standards, and health care providers and other participating entities must periodically demonstrate compliance.

- Reform health care financing to include risk adjustment for socioeconomic status in payment and in quality reporting.

- CMS should strengthen Medicaid managed care provider network adequacy standards by requiring a showing of accessibility and capacity to accommodate and by calling for networks to be expanded if found to be deficient.

- Allow activities that increase access and provider capacity to accommodate individuals with disabilities, including innovative ways to provide services, and include those activities as a bona fide element in medical loss ratio calculations.

- Accountable care organizations, accountable care collaboratives, medical homes, and health homes should integrate nonmedical community-based services and resources into their comprehensive service model of care. In particular, behavioral and physical health care services should be integrated across all health care delivery settings, including interoperable health information technology.

Yee, Havercamp, and their co-authors recommend that HHS should encourage and support states in broadening home and community-based offerings to better meet the need for long-term services and supports. Specifically, they recommend the following:

- Federal and state policies should promote a stable and appropriately skilled long-term services and supports workforce by improving job quality and should find ways to support family caregivers in continuing to provide the help that consumers need.

- HHS should require, and states should welcome, expanded efforts to measure the quality and outcomes of long-term services and supports, relying not only on administrative data but also on direct feedback from consumers.

- State agencies should be empowered to monitor quality and enforce requirements for high-quality services. The needs of consumers must be protected, including being fairly assessed for services by

___________________

8 Section 1115 of the Social Security Act gives the secretary of HHS authority to approve experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects that promote the objectives of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

-

entities without a conflict of interest, getting support in resolving problems encountered in dealing with managed care organizations, and being given the option of remaining in or returning to a fee-for-service system if needed.

- HHS and the states need to be especially vigilant in ensuring that managed care organizations retain and enhance the ability for consumers to direct their own services and continue to receive services that are not strictly health-care related but are more generally aimed at supporting people in participating fully in their communities.

TRANSLATING COVERAGE INTO HEALTH EQUITY: THE ROLE OF HEALTH LITERACY IN HEALTHY LIVING9

Community Catalyst is a national consumer health advocacy organization that supports consumer health advocates and their community partners in about 40 states. Its efforts are designed to ensure that all people have equal access to high-quality health care. Individuals with disabilities who are members of racial and ethnic minorities experience a double burden regarding the layers of inequity they face. In this population, said Stahl, social determinants of health are more numerous and have a bigger impact, resulting in the individuals in this double burden situation having worse health outcomes.

There is a need for more research at the intersection of race, ethnicity, and disability, noted Havercamp and Yee. The research that has been done shows that members of racial and ethnic minorities who have a disability face greater health disparities than their peers without a disability, said Stahl (Blick et al., 2015). This situation, she said, raises issues about social justice and health equity, the role of implicit bias, and the need to include the goal of reaching optimal health across all policies and platforms as a means of dismantling these damaging constructs. “When we look at how we move ourselves forward, it’s really about braiding these strands of research together but also braiding the strands of the advocacy as well,” said Stahl.

For her and her colleagues working with members of the community, health literacy is the primary tool for achieving health equity, for in their view health literacy is about empowering consumers. The domains of

___________________

9 This section is based on the presentation by Eva Marie Stahl, director of the Community Catalyst Children’s Health Project at Community Catalyst, and Rosa Palacios, consumer engagement specialist with the Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation at Community Catalyst, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

health literacy in which Community Catalyst works to foster self-advocacy includes increasing the personal knowledge base of individuals, teaching them about the tools to seek and understand new information, and using that information to solve problems when they face barriers. Health literacy, said Stahl, is a tool to provide disability access, which includes physical access to providers as well as vision and hearing supports and cultural and language access by including providers who speak the individual’s preferred language and who can deliver culturally competent care. Also important is providing long-term support to enable a person with disabilities to always experience health literate and coordinated care.

Commenting on the term health in all policies, Stahl sees this emphasis on being responsive to the whole person as an opportunity to make sure that Medicare, Medicaid, and federal and state budgets are policy vehicles for supporting health literacy and empowering consumers. She also noted that as health systems innovate with new delivery models, they have the opportunity to prioritize consumer engagement and health literacy with transformation efforts. “What does it look like when consumer engagement is built into the system, and how do we invest in the tools around health literacy to ensure that those consumers are empowered to be a part of the delivery system?” asked Stahl.

As examples of the programs Community Catalyst is working with, Stahl described the family engagement initiative being conducted by the Federation for Children with Special Health Care Needs in Massachusetts.10 This effort is using a quality demonstration grant, awarded as part of the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA), to make a specific investment in family engagement as a means of supporting children with special health care needs. The My Health, My Voice project,11 run by the national organization Raising Women’s Voices,12 created a set of tools to help newly insured women get the most from their health insurance. Community Catalyst is also supporting a project in Missouri using health literacy tools outside of the health care system to ensure that individuals in an addiction recovery program who are exiting the criminal justice system—many of whom have chronic health conditions—have access to the tools to help them succeed when they reenter the community. In Rhode Island, the Rhode Island Parent Information Network is leveraging the community health worker in a peer-learning model to help persons of color who have disabilities engage in primary care.13

Palacios then discussed new evidence-based self-management programs

___________________

10 See http://fcsn.org (accessed October 10, 2017).

11 See http://www.myhealthmyvoice.com (accessed October 10, 2017).

12 See http://www.raisingwomensvoices.net (accessed October 10, 2017).

13 See http://www.ripin.org (accessed October 10, 2017).

for promoting health literacy and health equity that Community Catalyst is supporting as a means of achieving the quadruple aim. The Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program teaches three major skills, and she noted that it is the process used to teach these skills, rather than the subject matter, that makes this program effective. This process relies on four strategies to increase self-efficacy. Skills mastery teaches participants how to make and execute a weekly action plan and provide feedback on how the action plan activities are going. “It is through these activities that participants begin to master the tasks they want to accomplish, giving them increased confidence in their ability to deal with the symptoms and problems caused by their health conditions,” explained Palacios.

The second strategy is modeling through problem-solving activities with peers. “People do better when taught by people like themselves, which is why this program is led by trained lay people.” This strategy shows participants that self-management is possible, increasing their belief that they can manage their own health care needs. The third strategy teaches participants how to reinterpret their symptoms. “People act based on what they believe about their conditions, so by helping them change or expand their belief about the causes of their symptoms they can begin to try new things to help relieve their symptoms and resolve their problems,” said Palacios. For example, she said, if someone believes fatigue is caused by their disease, they will probably feel helpless, but when they learn that fatigue can have other causes—medication, lack of exercise, poor nutrition, stress, and others—they can see there may be something they can do.

Persuasion is the fourth strategy, and it occurs when participants are gently persuaded to try new activities and use new tools and techniques when making their weekly action plans. This type of persuasion also helps support individuals to make other changes, further increasing their confidence that they are able to manage their condition, said Palacios. She noted that in addition to these confidence-building skills, this program uses other methods, such as lectures, pairing and sharing, brainstorming, call-outs, problem solving, and decision making, to encourage participants as they make changes in their lives to better support their health goals.

Each program consists of six 2.5-hour sessions, and there are several versions in many languages being offered in diverse communities across the country. Through these programs, which were developed at the Stanford University Patient Education Research Center and are integrated within the health care delivery system, participants obtain knowledge about the processes involved in accessing care and the services they need to make appropriate health decisions, increasing their health literacy as they go through the program and becoming empowered individual advocates.

These programs are being implemented in diverse community settings within the health care delivery system; for example, in medical homes, ac-

countable care organizations, dual eligible plans, and other shared-risk pilot programs. They are using a variety of models to integrate these programs, such as the Commonwealth Care Alliance and Iora Health,14,15 and use community health workers and health educators by offering the program to their members as a health plan benefit. Others contract with community-based organizations or offer the program as a reimbursable wellness benefit. In Massachusetts, a statewide disease management coalition, Healthy Living 4 Me,16 has a website that provides centralized referrals to a local program, and it offers technical assistance and has established a learning collaborative and quality assurance processes for the programs offered in the state. These programs target a wide range of populations that experience poorer health compared with the overall U.S. population (see Table 2-1).

In closing, Palacios said that Massachusetts’ My Life, My Health version of this program has been shown to help participants improve their health behavior (Ahn et al., 2013). Individuals who completed the six-session course reported decreased symptoms of depression and significant improvements in self-assessed health, quality of life, fatigue, sleep, pain, and shortness of breath. They were also more likely to engage in moderate physical activity and experience better health care as measured by improved communication with their physicians and improved medication compliance. In addition, those who completed the program had significantly reduced risks of visiting the emergency department and significantly lower odds of hospitalization over the subsequent 6 months. As a result, it is estimated that net savings, after accounting for the cost of the program, were $364 per individual per year.

Palacios also noted that physicians have reported seeing dramatic changes in their patients after going through this program. Patients, they report, are more empowered to play a role in their own care, are better able to manage their medications and advocate in a proactive way with their care managers, and work more effectively with community health workers. At the system level, patients report being more satisfied with their health care based on the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) scores. She added that at the policy level, the Administration for Community Living and the National Council on Aging are now working to get these evidence-based programs to be included in the benefits for all health plans in every state.

___________________

14 See http://www.commonwealthcarealliance.org (accessed October 10, 2017).

15 See http://www.iorahealth.com (accessed October 10, 2017).

16 See http://www.healthyliving4me.org (accessed October 10, 2017).

TABLE 2-1 Vulnerable Populations Targeted by Community Catalyst’s Projects

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Total | National | Change from Year 1–3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 1,612 | 2,487 | 2,506 | 6,605 | — | 55.46% |

| Completers | 1,235 | 1,932 | 1,917 | 5,084 | — | 55.22% |

| Completion Rate | 76.60% | 77.70% | 76.60% | 77.00% | 73.20% | 0.00% |

| Native American | 3.40% | 1.10% | 1.40% | 1.97% | 2.30% | −58.82% |

| Asian | 10.20% | 3.60% | 8.50% | 7.43% | 4.20% | −16.67% |

| Black | 6.60% | 13.30% | 18.20% | 12.70% | 22.20% | 175.76% |

| Latino | 9.40% | 16.80% | 22.70% | 16.30% | 17.10% | 141.49% |

| Caregiver | 16.30% | 22.00% | 29.10% | 22.47% | 29.20% | 78.53% |

| Disability | 50.50% | 48.10% | 53.10% | 50.57% | 45.00% | 5.15% |

SOURCE: Stahl and Palacios slide 19 (previously unpublished data).

DISCUSSION

Yee was asked by a workshop participant if lumping the disparate conditions and challenges of the heterogeneous population of individuals with disabilities under the broad rubric of disability creates challenges to enacting laws that provide equal accommodation across disparate conditions. She replied that when the ADA was being written the organizing principle was that regardless of the specific disability, the common barrier individuals face is discrimination. As a result, the law focuses on reasonable accommodations that enable any person with a disability to be able to participate equitably in society and emphasizes negotiation in an iterative process to achieve equity, primarily in the workplace. “Ideally, that is also what happens in the health care situation,” said Yee, for no regulation can address every possible situation. Instead, the law creates a framework for how to approach a person with a disability and requires providers, hospitals, and other health care professionals in a health care system to talk with those with disabilities to figure out what they need and how to accommodate that need. Individuals with disabilities, except perhaps those with newly acquired disabilities, know very well what they need to live life to the fullest and obtain appropriate health care. Stahl added that another function of the law is to point to what discrimination looks like and how to address it.

Jeffrey Henderson from the Black Hills Center for American Indian Health commented that multiple datasets have measured the quality of life of AIAN populations, and an analysis of the psychometric properties of these instruments arrived at the surprising conclusion that the happiest participants by measure of their mental health component summary score were Lakota males with lower-extremity amputations. He also noted that there has been a massive buildup over the past decade of infrastructure for home health care in western South Dakota and asked the speakers if the ACA provides the opportunity to properly allocate resources in the home health care infrastructure to support individuals with disabilities who wish to remain in the home environment. Stahl replied, and Yee agreed, that the ACA, through the many waiver mechanisms it created, does offer that opportunity. However, taking advantage of it requires a great deal of work and a strong coalition of advocates who can influence the development of programs at the state level.

Yee added that Medicaid restricts who can be a home care assistant to an individual in his or her home, and this can have a profound effect on someone with a disability. She recounted the story of a Native American with a disability who wanted to hire a relative to be his home care assistant because nonrelatives were unwilling to make regular trips back to his hometown, something that was important to him. That he was not

allowed to do so under Medicaid regulations put into relief how state-level Medicaid policies can have a big impact on meeting the needs of individuals with disabilities.

She added that the lack of nationally recognized quality measures for long-term services and supports creates challenges for knowing whether any of the pilot programs created under the provisions of the ACA are effective at improving health care equity for individuals with disabilities. As a result, change is taking place slowly because these programs are not being disseminated. Villarruel noted that this is not a problem unique to programs aimed at those with disabilities. Stahl commented that one effective strategy to overcome inertia against change at the national level is to coordinate scale-up activities at the state level. As an example, she said that the Native American communities in Michigan received funding from CDC to establish their own Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Tom Wilson from Access Living remarked that for many people the gold standard for home and community-based services is consumer control. “If you can control your life and want to control your life, you should have the ability to make those decisions for yourself,” said Wilson. “We see when we talk to people that the greatest satisfaction is when people have that control over their services. All too often, states and other things restrict that.” As an example, states often prohibit people with felony convictions from becoming personal assistants, yet those individuals, he said, can make good home care and personal assistants, said Wilson. Another example is the regulation that caps personal assistant workload at 40 hours per week, even though many personal assistants cannot afford to live without the ability to earn overtime pay, forcing them out of the field. Both examples, said Wilson, highlight state actions that take away control from the person who has a disability.

Jennifer Dillaha from the Arkansas Department of Health voiced her support for the notion of shifting disability from being a health outcome to a demographic feature, but she wondered how effectively EHRs were capturing disability. Yee said that such information is not routinely collected in EHRs and that she and her colleagues have been working with the Consumer Partnership for eHealth to advocate for including the six HHS questions in EHRs (see the questions listed earlier in this chapter).

These questions, Yee noted, have been validated and tested for their ability to obtain accurate and consistent results across different populations, yet she knows of no cases where those questions are included in an EHR. A detailed review that she and her colleagues conducted of the technical document that describes the types of medically oriented information that may be included in an EHR did find some information regarding functional limitations, but now the challenge is to turn it into practical

policy that will provide useful demographic information. “I do not know how to even get those conversations started,” said Yee.

Stahl noted that there has been progress around getting information on the social determinants of health into the EHR. In Massachusetts, for example, EHRs now contain food access and housing fragility screens, and the answers to those screens can trigger a connection to human services. The question, however, is whether gathering data about functional limitations from a person on Medicaid would provide a prompt to inquire about that individual’s transportation needs, for example. Stahl acknowledged that this is a highly technical problem, but one that needs to be solved. She also raised the problem of information exchange, where two physicians treating the same individual cannot see what each other has noted in that individual’s EHR. “There is no exchange of information, and when you add in the layers of social determinants of health, it’s a quagmire,” said Stahl.

Havercamp commented that having information on functional limitations in the EHR, assuming that information was accessible and usable, would allow providers to anticipate and accommodate for functional limitations at every health care visit. Too often, individuals might mention to appointment schedulers that they need some accommodation but that information is not recorded in the EHR or communicated to the providers who see those individuals. As a result, those accommodations are not in place at the time of their appointments, and they have less than satisfactory visits. Stahl added that having such information in the EHR would further consumer empowerment.

Villarruel referred to a 2014 Institute of Medicine report that addressed the importance of capturing data on the social determinants of health in the EHR (IOM, 2014), and she wondered if that report also addressed disabilities. Rose Marie Martinez from the National Academies’ Health and Medicine Division replied that disabilities were not included in that report.

Francisco García from the Pima County Health Department in Arizona said he finds the concept of using the accreditation process as a means of ensuring that people can take action on the rights that various laws bestow on them intriguing. He suggested that data collected on disabilities could trigger an action item if they were included as part of an accreditation process. “Yes, [that information] can inform the individual visit when we collect information about disability, but it could be a way that we document our compliance or document our ability to meet the needs of the population,” said García.

Havercamp responded by noting there is currently no requirement for future physicians to get any disability training whatsoever. “Anything that a medical student learns about disability is thanks to an individual champion in his or her program,” said Havercamp, with regard to accrediting physicians. She and her colleagues have been working with the Alliance for

Disability and Health Care Education to create a set of competencies for health care providers that they hope will be added to training standards for future health care providers. In nursing, she added, there have recently been a few guidelines and competencies inserted into some nurse training programs, while in public health, the Association of University Centers on Disabilities just created a document for disability competencies for the public health workforce (AUCD, 2016). “I think it is an important tool,” said Havercamp.

Yee recounted that the Joint Commission developed some guidelines around disabilities several years ago, but she did not believe that there is a requirement to provide accommodations for those with disabilities in order to receive accreditation. The lack of connection between federal laws, disability civil rights, and the bodies that certify providers, hospitals, and various health care entities needs to be addressed, said Yee. Where requirements are being addressed is in managed care control language in states such as California and Massachusetts, though she said she doubts that the third-party reviewers who visit the contracted organizations are making sure that providers’ offices are accessible or that there are procedures in place to accommodate someone who is deaf and needs an interpreter. “When it comes down to that level of policy and procedure, I do not think that anyone is checking,” said Yee. While contract language is a good first step, monitoring and enforcement are the next steps that need to be taken, she added.

Wilma Alvarado-Little from Alvarado-Little Consulting, LLC, asked the speakers if any considerations were being made to make members of the community aware of the rights they have, particularly in communities in which English is not the primary language. Stahl responded that one of her organization’s primary areas of focus is to work with community-based organizations to make sure they are engaged and informed so they can in turn inform the members of their communities, and she believes that progress is happening. “We see advocates really striving to do this work,” said Stahl. In Illinois, for example, the advocates her organization works with are training their navigators, their community-based organizations, their insurers, and provider groups about health literacy. The challenge, she said, is to think systematically about how to build those efforts into the health care system and fund them so these community groups will not have to keep doing this work for free. She noted, too, that these activities are being conducted in English and other languages.