5

Federal, State, and Regional Management Efforts

1. BRIEF HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF BRUCELLOSIS CONTROL EFFORTS

In 1934, as part of an economic recovery program during the Great Depression to reduce the cattle population, efforts were initiated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to eradicate brucellosis caused by Brucella abortus in the United States. This was seen as an opportunity to address the most significant livestock disease problem facing the country at that time, with brucellosis affecting 11.5% of adult cattle in 1934 and 1935 (Ragan, 2002). Recognizing the magnitude of the negative economic impact of brucellosis on the cattle industry and on human health, the U.S. Congress appropriated funds in 1954 for a comprehensive national effort to eradicate brucellosis. The brucellosis eradication program required cooperation between federal agencies, states, and livestock producers (Ragan, 2002). The eradication program has been modified several times since then as the science and technology of brucellosis has developed over the years through research and experience. There were a number of key developments that were major turning points in the program. Some of these were advances in technology, while others were procedures learned through trial and error (Ragan, 2002). The brucellosis eradication program made tremendous progress, resulting in a dramatic decrease in brucellosis-affected cattle herds in the United States over time. At the end of 2001, for the first time in the United States, there were no known brucellosis-affected herds remaining (USAHA, 2001). The number of human brucellosis cases also declined steadily over the course of the brucellosis eradication program. There are now only about 100 cases of human brucellosis reported per year, most often associated with travelers who have consumed unpasteurized milk and milk products abroad that were infected with B. melitensis (Glynn and Lynn, 2008).

2. CHANGES IN STATUS AND CLASSIFICATION OF STATES

Brucellosis regulations have provided a system of classifying states or areas within states based on incidence of findings of brucellosis in cattle or privately owned bison herds within the state or area (9 CFR Part 78). The classifications are Class Free, Class A, Class B, and Class C. As each state moves or approaches Class Free status, restrictions on interstate movement of cattle and domestic bison become less stringent. The achievement of Class Free status has historically been based on the finding of no B. abortus-infected herds within the state or area within 12 months preceding classification as Class Free, with documentation of adequate surveillance. Maintenance of Class Free status by states or areas requires surveillance through biannual ring testing at dairies and slaughter surveillance from at least 95% of all cows and bulls 2 years of age or over at each recognized slaughtering establishment.

In 1997, the Brucellosis Emergency Action Plan was initiated and it emphasized rapid response, enhanced surveillance, epidemiology and herd management, and depopulating affected herds. All activities involving new cases of brucellosis and brucellosis surveillance were handled as a top priority. As part of the new emphasis, herds identified with brucellosis in a Class Free state had to be depopulated within 60 days of diagnosis in order for that state to continue to be designated as Class Free. Two herds diagnosed with brucellosis in any 24-month period was cause for downgrade to Class A status.

In February 2008, every state, along with the territories of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, achieved Class Free State status for the first time in the 74-year history of the U.S. brucellosis program. This accomplishment was short-lived, however, as Montana lost its Class Free status in September 2008 after two brucellosis-affected cattle herds were found within 1 year. Recognizing the success of the Brucellosis Eradication Plan across the United States, and that the last known wildlife reservoir of B. abortus exists in the bison and elk populations in the Greater Yellowstone Area (GYA), USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) determined that a new direction was necessary to allow Veterinary Services and the states to apply limited resources effectively and efficiently to this disease risk (USDA-APHIS, 2009).

In 2010, USDA-APHIS published an interim rule that made several changes to the regulations consistent with the goal of shifting resources to more efficiently address B. abortus control and eradication in the domestic livestock population. States that had been classified as brucellosis Class Free for 5 or more years now maintain status without Brucellosis Milk Ring Surveillance (BMST), and slaughter surveillance nationwide has been significantly reduced. Instead of depopulating herds, states or areas can maintain Class Free status while managing herds affected with brucellosis under quarantine with an approved herd plan.

Under the interim rule, specific requirements are imposed on states with infected wildlife reservoirs to ensure that the spread of B. abortus between wildlife and livestock is mitigated. The rule also moved away from requirements for automatic status downgrades in states when two or more herds are identified with brucellosis within 24 months or if an infected herd is not depopulated within 60 days. Instead, USDA-APHIS allows states to maintain Class Free status if the state makes appropriate disposition of any affected herds and conducts surveillance “adequate to detect brucellosis if it is present in other herds or species” (USDA-APHIS, 2010).

3. REGIONAL AND NATIONAL CONTROL PROGRAMS

USDA-APHIS has the regulatory authority to manage animal diseases in livestock. However, brucellosis in the GYA is complicated by the fact that there are a multitude of federal and state agencies involved, with differing mandates, management responsibilities, and authorities. Although regulated livestock disease programs generally fall under USDA-APHIS and state animal health agencies, wildlife are managed by state wildlife agencies and the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI). Thus, USDA-APHIS cooperates with state wildlife management agencies in the management of wildlife diseases and with state animal health and livestock agencies in the management of livestock diseases. Management of national parks falls under the purview of the National Park Service (USDOI and USDA, 2000).

3.1 Involvement of Federal Agencies

Within the boundaries of Yellowstone National Park (YNP), the Secretary of the Interior has exclusive jurisdiction to manage the Park’s natural resources, including bison and elk (USDOI and USDA, 2000). When the bison and elk are outside of YNP on National Forest Service lands, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) has responsibilities under federal laws to provide habitat for wildlife. Federal law also requires USDA-APHIS to control and prevent the spread of communicable and contagious diseases of livestock. Therefore, depending on what lands the bison or elk are located on, management responsibilities and authorities differ and change when wildlife cross certain boundaries. Table 5-1 below illustrates federal agency jurisdiction and involvement.

TABLE 5-1 Federal Agency Jurisdiction and Involvement in Brucellosis

| Federal Agency | Mission | Relevant Jurisdiction | GYA Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| USDA: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service |

To protect the health and value of American agriculture and natural resources. | Federal law requires APHIS to control and prevent the spread of communicable and contagious diseases of livestock. |

|

| USDA: U.S. Forest Service |

To sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations. | When the bison are on national forest system lands, the U.S. Forest Service has responsibilities under federal laws to provide habitat for the bison, a native species. |

|

| DOI: National Park Service–Yellowstone National Park (YNP) |

To preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. The Park Service cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation throughout this country and the world. | Within the boundaries of YNP, the Secretary of the Interior has exclusive jurisdiction to manage the parks natural resources, including bison and elk. |

|

| DOI: National Park Service–Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) |

To preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. The Park Service cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation throughout this country and the world. | Within the boundaries of GTNP, the Secretary of the Interior has exclusive jurisdiction to manage the parks natural resources, including bison and elk. |

|

| Federal Agency | Mission | Relevant Jurisdiction | GYA Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOI: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, National Elk Refuge |

Working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. | The National Elk Refuge provides, preserves, restores, and manages winter habitat for the nationally significant Jackson elk herd as well as habitat for endangered species, birds, fish, and other big game animals. |

|

| DOI: Bureau of Land Management |

To sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. | Administer grazing permits and leases for livestock on BLM managed land. |

|

SOURCES: USDOI and USDA, 2000; USDA-APHIS, 2015; BLM, 2016; FWS, 2016a,b,c,d; NPS, 2016a; USFS, 2016.

3.2 Involvement of State Agencies

The Idaho State Department of Agriculture, the Wyoming Livestock Board, and the Montana Department of Livestock each have authority and responsibility for livestock disease control and eradication, regulation of livestock importation into the state, and protection of the livestock interests of the state. The mission of the Montana Department of Livestock also includes the responsibility to prevent the transmission of animal diseases to humans. The agencies are also responsible for overseeing brucellosis surveillance in livestock, managing the risk of brucellosis to livestock in the GYA, and prevention and response efforts to any brucellosis outbreaks in livestock in their respective states. Furthermore, the agencies are responsible for the designation of and management of the brucellosis designated surveillance areas (DSAs) in their respective states.

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG), the Wyoming Game & Fish Department (WGFD), and the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks (MFWP) are responsible for wildlife management in their respective states, including preserving and protecting wildlife and managing wildlife hunting. Table 5-2 illustrates state agency jurisdiction and involvement.

Test and Remove Pilot Program in Elk

Since 1912, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) has implemented a supplemental feeding program on the National Elk Refuge (NER) for the purpose of sustaining elk populations, reducing winter mortality, and reducing crop damages on private lands. The same rationale was cited by WGFD for commencing a supplemental feeding program in 1929. Today, between 20,000 and 25,000 elk are fed annually along the 22 feedgrounds in western Wyoming (in Lincoln, Sublette, and Teton Counties) and the NER (Scurlock et al., 2010).

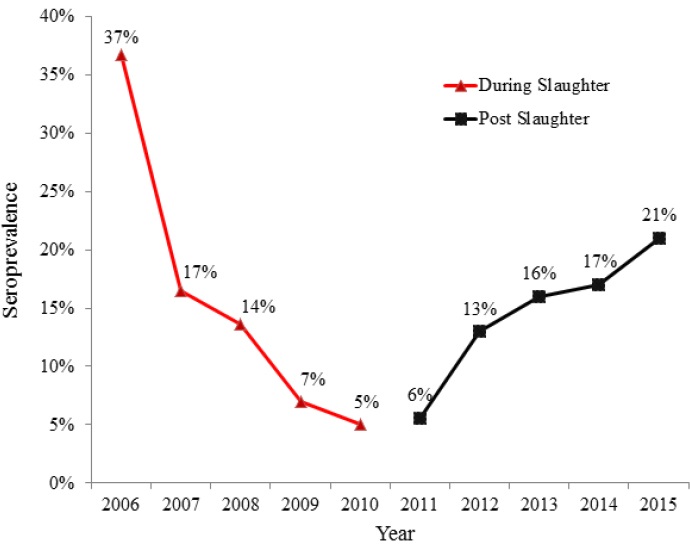

WGFD implemented a $1.2 million pilot project occurring over a 5-year span to reduce brucellosis prevalence in elk. From 2006-2010, a test-and-remove strategy targeted three feedgrounds in the Pinedale elk herd unit. This pilot project was endorsed by the Wyoming Brucellosis Coordination Team (WBCT) and conducted in response to a goal of reducing seroprevalence and eventually eliminating brucellosis in wildlife, specifically addressing winter elk feedgrounds (WBCT, 2005). Male elk were not targeted due to their insignificance in brucellosis transmission. Although at least two trapping attempts were conducted every year, only 49% of adult and yearling female elk available were captured and tested. Brucellosis seroprevalence reductions were also observed on the two other feedgrounds included in the study (Scurlock et al., 2010).

During the pilot project, the seroprevalence of B. abortus decreased significantly in elk captured at the Muddy Creek feedground: from 37% in 2006 to 5% in 2010 (Scurlock et al., 2010) (see Figure 5-1). In 2007, seropositive elk that were also culture positive ranged from 36% in Scab Creek to 77% at Muddy Creek. The results of this pilot project showed reduced seroprevalence by more than 30 percentage points in 5 years as a result of capturing nearly half of available yearling and adult female elk attending a feedground and removing those that tested seropositive. Seroprevalence trends on other state feedgrounds did not result in a similar decrease in seroprevalence, which indicates that removing seropositive individuals reduces prevalence beyond natural oscillations (Scurlock et al., 2010). Although the seroprevalence was significantly reduced, brucellosis transmission events were not disrupted because only half of the elk were captured. After the 5-year pilot project was discontinued, the seroprevalence of brucellosis in elk on the feedgrounds resurged.

TABLE 5-2 State Agency Jurisdiction and Involvement in Brucellosis

| State Agency | Mission (Relevant Sections) | GYA Involvement |

|---|---|---|

| Idaho State Department of Agriculture |

|

Oversees administration of the designated surveillance areas (DSAs) in Idaho. Responsible for brucellosis control and eradication in livestock. |

| Montana Department of Livestock | To control and eradicate animal diseases, prevent the transmission of animal diseases to humans, and to protect thelivestock industry from theft and predatory animals. | Oversees administration of the DSA in Montana. Responsible for brucellosis control and eradication in livestock. |

| Wyoming Livestock Board | “The Wyoming Livestock Board Animal Health Unit exercises general supervision over and protection of thelivestock interests of thestate from disease by implementing board rules and regulations, assisting in enforcement, monitoring the import of livestock and biologic agents into the stateand disseminating lawful and accurate information.” | Oversees administration of the DSA in Wyoming. Responsible for brucellosis control and eradication in livestock. |

| Idaho Department of Fish and Game | “All wildlife, including all wild animals, wild birds, and fish, within the state of Idaho, is hereby declared to be the property of the state of Idaho. It shall be preserved, protected, perpetuated, and managed. It shall be only captured or taken at such times or places, under such conditions, or by such means, or in such manner, as will preserve, protect, and perpetuate such wildlife, and provide for the citizens of this state and, as by law permitted to others, continued supplies of such wildlife for hunting, fishing and trapping.” | Works to maintain or improve game populations to meet the demand for hunting. Works to reduce or eliminate the risk of transmission of disease between captive in free ranging wildlife. Collaborates with other agencies and education institutions on disease control, prevention, and research. |

| Wyoming Game & Fish Department | Provides an adequate and flexible system of control, propagation, management, and protection and regulation of all wildlife in Wyoming. | Manages 22 state-operated elk feedgrounds in Wyoming. Also oversees Brucellosis Management Action Plans (BMAPs) for elk herds as well as the Jackson bison herd and the Absaroka bison herd. |

| Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks | Provides for the stewardship of the fish, wildlife, parks, and recreational resources of Montana while contributing to the quality of life for present and future generations. | Administers elk management plans in Montana. Conducts and participates in research projects related to brucellosis in elk. |

SOURCES: IDFG, 2015, 2016; MFWP, 2016a,b; WGFD, 2016a,b; Wyoming Livestock Board, 2016.

Use of Feedgrounds for Separating Cattle from Elk

Although elk are currently considered one of the primary reservoirs of B. abortus, feedgrounds serve as a primary method to maintain separation of elk and livestock and prevent intraspecies transmission of brucellosis (Maichak et al., 2009). In Wyoming alone, 22 elk feedgrounds and the NER support up to 25,000 elk (Maichak et al., 2009). With brucellosis transmitted from elk to cattle in the GYA (Rhyan et al., 2013), minimizing contact between the two species on feedgrounds has become even more important. There is the perception that feedgrounds reduce the risk of interspecies brucellosis by separating elk and domestic cattle. However, several cases of brucellosis have been discovered in cattle near feedgrounds (FWS, 2016d).

Vaccination of Elk on Wyoming Feedgrounds

Vaccination of wildlife has been shown to reduce and in some cases eliminate diseases from host wildlife populations (Plumb et al., 2007). Oral rabies vaccine (ORV) in wildlife has been used in several European countries to successfully eliminate rabies in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes). In the United States, the integration of ORV into the dog vaccination program was a major factor leading to the country’s canine-rabies-free status, which was declared in 2007 based on World Health Organization standards (Slate et al., 2009).

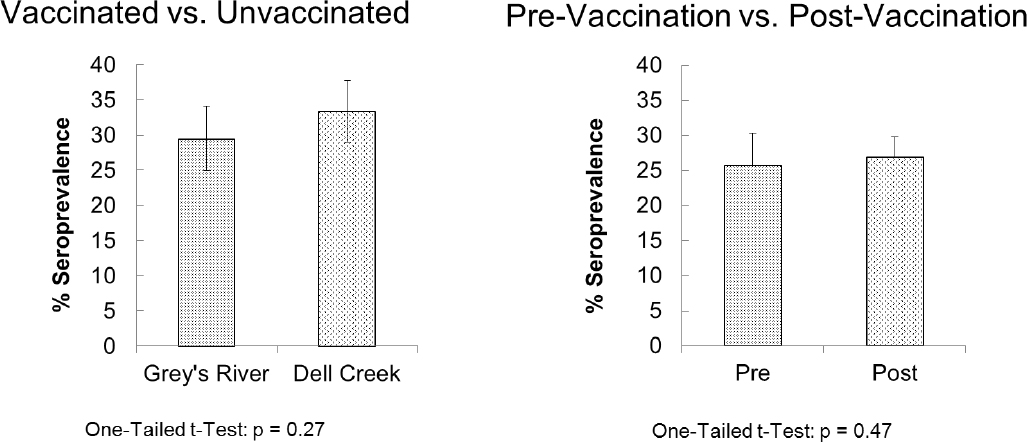

In 1985, a Brucella abortus strain 19 (S19) vaccination program began on the elk feedgrounds in Wyoming due to a high seroprevalence of brucellosis in elk. S19 was delivered via biobullet to animals frequenting the feedgrounds (Scurlock, 2015). From 1985-2015, approximately 91,145 juvenile elk (99% average vaccinated per year) and 19,336 adults (6% average vaccinated per year) were vaccinated with S19 (Scurlock, 2015). In comparing the seroprevalence of feedground elk before and after vaccination, there are no relevant effects of vaccination (see Figure 5-2). In addition, the amount of vaccination coverage at a feedground did not correlate with reduced seroprevalence after accounting for confounding factors. Finally, the seroprevalence at vaccinated feedgrounds was not demonstrably lower than a non-vaccinated feedground (Maichak et al., 2017).

Numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of S19 in elk relative to protection from abortion and or infection. In a controlled challenge study, S19 vaccine provided low protection against abortion and no protection from infection (Roffe et al., 2004). In addition, single abortions on feedgrounds may expose many elk, and individual elk could receive multiple exposures from more than one fetus. Therefore, a naturally acquired challenge dose for exposed animals could easily and realistically be much higher than an experimental challenge dose (Roffe et al., 2004). A single calfhood vaccination of elk with S19 produces a very low level of immunity in vaccinated elk and would be highly unlikely to lead to significant reduction or eradication of brucellosis from feedground elk (Roffe et al., 2004). However, other challenge studies have indicated that S19 provided modest protection against reproductive failures (Thorne et al., 1981; Herriges et al., 1989).

One possible reason for the inconsistent findings relative to S19 efficacy in various experimental and field conditions may be related to frequent and highly concentrated exposure to fetal abortion materials (such as tissues and fluids) on feedgrounds. Two factors appear to drive the transmission of B. abortus: there are massive amounts of B. abortus present in the placental fluids and general exudates from the aborting female, combined with the strong attractant effect of expelled fetal membranes (NRC, 1998). Elk-fetus contact levels were highest when fetuses were placed on traditional feedlines (Maichak et al., 2009). Recent fetal contact studies on an elk feedground have shown that more than 30% of a population can be exposed to one fetus or abortion within 24 hours (Creech et al., 2012). This high rate of exposure to aborted materials minimizes the effect of vaccination as the likelihood of infection is related to the dosage of the infectious challenge, and each gram of aborted material tissues typically has billions of Brucella organisms (Enright, 1990).

In 2013, SolidTech Animal Health, Inc., the sole producer of biobullets and projectors, terminated their ballistic technologies division and had not sold the rights or equipment to produce biobullets (Scurlock, 2015; Maichak et al., 2017). Therefore, remote vaccination of elk with S19 vaccine is no longer an option for managers at this time.

4. INTERAGENCY COOPERATIVE BODIES

Several cooperative state and federal interagency bodies were developed to address brucellosis-specific issues in the GYA: the Greater Yellowstone Interagency Brucellosis Committee (GYIBC), the Interagency Bison Management Plan (IBMP), and WBCT.

4.1 Greater Yellowstone Interagency Brucellosis Committee

GYIBC was formed in 1995 through a memorandum of agreement signed by the Secretaries of Agriculture and of the Interior and by the governors of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming (Brunner et al., 2002). The GYIBC consisted of an executive committee, two subcommittees, a technical subcommittee, and an information and education subcommittee (NPS, 2016b). Governmental representatives to the committee included the state veterinarians and directors of state wildlife agencies from the states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Federal voting members of the GYIBC executive committee included USDA-APHIS Veterinary Services, USDA Forest Service, the National Park Service (DOI), U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (DOI), and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). There were also three nonvoting members represented on the GYIBC committee: the U.S. Geological Survey, USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, and the InterTribal Bison Cooperative (OMB, 2007).

The goal of the GYIBC was to protect and sustain the existing free-ranging elk and bison populations in the GYA and to protect the public interests and economic viability of the livestock industry in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming (GYIBC, 2005). Toward this end, the mission of the GYIBC facilitated the development and implementation of brucellosis management plans for elk and bison in the GYA (GYIBC, 2005).

The GYIBC had a number of management objectives intended to guide their activities (GYIBC, 2005):

- Recognize and maintain existing state and federal jurisdictional authority for elk, bison, and livestock in the GYA;

- Maintain numerically, biologically, and genetically viable elk and/or bison populations in the respective states, national parks, and wildlife refuges;

- Maintain the brucellosis-free status of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming and protect the ability of producers in the respective states to freely market livestock;

- Eliminate brucellosis-related risks to public health;

- Eliminate the potential transmission of B. abortus among elk, bison, and livestock;

- Coordinate brucellosis-related management activities among all affected agencies;

- Base brucellosis-related management recommendations on defensible and factual information while encouraging and integrating new advances and technology;

- Aggressively seek public involvement in the decision-making process;

- Communicate to the public factual information about the need to prevent the transmission of brucellosis, the need for its eradication, and the rationale for related agency management actions; and

- Plan for elimination of B. abortus from the GYA by the year 2010.

In May 2005, after the GYIBC memorandum of understanding (MOU) expired, USDA and DOI agreed on a revised GYIBC MOU and presented the draft to the governors of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming for consideration (U.S. Congress, 2007). The revised MOU was ultimately not signed by the governors, and the GYIBC was disbanded.

4.2 Interagency Bison Management Plan

The IBMP was developed to address the issue of bison exiting YNP and entering the state of Montana. Signed in 2000, the IBMP was a result of federal and state agencies recognizing that a coordinated, cooperative management regime was necessary for providing consistency and reliability to the process of managing bison that move from YNP into Montana. This interagency management plan resulted from 10 years of mediated negotiations in Montana between agencies to come to agreement. The IBMP was strictly a plan to manage bison that exit YNP and enter the state of Montana. It was not intended to be a brucellosis eradication plan; rather it was meant to be a means to manage bison and cattle to minimize the risk of interspecies transmission. The IBMP also states that “these management actions demonstrate a long-term

commitment by the agencies to work towards the eventual elimination of brucellosis in free ranging bison in Yellowstone National Park” (USDOI and USDA, 2000).

Specifically, the IBMP seeks to (IBMP, 2016):

- Maintain a wild, free-ranging bison population;

- Reduce the risk of brucellosis transmission from bison to cattle;

- Manage bison that leave YNP and enter the state of Montana; and

- Maintain Montana’s brucellosis-free status for domestic livestock.

The IBMP has been effective in maintaining the separation of bison and cattle, and there is no evidence that there has been transmission of brucellosis from wild bison to cattle in the GYA since the IBMP was implemented. Management of elk was outside the scope the IBMP negotiated agreement (USDOI and USDA, 2000). The IBMP is evaluated regularly and modified as needed through adaptive management.

4.3 Wyoming Brucellosis Coordination Team

The WBCT was created in 2004 by the governor of Wyoming to address the issue of brucellosis for Wyoming. The impetus for the formation of the WBCT resulted from a case of brucellosis in a herd of cattle from Sublette County, Wyoming. This case is believed to be the result of contact with infected elk from the nearby Muddy Creek elk feedground area (Galey, 2015). The WBCT included 19 members and 10 technical advisors, including sportsmen, outfitters, ranchers, state, university, legislators, federal managers, and representatives from the governor’s office (Galey, 2015).

The WBCT was tasked “with identifying issues, describing best management practices, and developing recommendations related to brucellosis in wildlife and livestock in the state” (WBCT, 2005). It was also asked to provide recommendations that detail actions, responsibilities, and timetables where appropriate. In 2005, the WBCT presented a report to the governor of Wyoming that contained 28 specific recommendations for action under four topic areas (WBCT, 2005). The four topics include “(1) reclaiming Class-Free brucellosis status for cattle, surveillance, and transmission between species; (2) developing an Action Plan of what to do in the event of a new case in cattle; (3) addressing human health concerns; and (4) reducing and eventually eliminating brucellosis in wildlife, specifically addressing winter elk feedgrounds” (WBCT, 2005). Many of the recommended measures have been implemented, and the WBCT continues to meet biannually to combine efforts of agencies, landowners, and others to move the Wyoming brucellosis management issue forward.

5. SURVEILLANCE

5.1 National Surveillance for Brucellosis

The Market Cattle Identification (MCI) surveillance program was formerly comprised of samples collected from at least 95% of test-eligible adult dairy and beef cattle presented for slaughter at all state and federally recognized slaughter establishments, as well as from adult cattle offered for sale at livestock auction markets. This surveillance stream provided a 99% confidence level that the prevalence of brucellosis was less than one infected animal per one million animals (0.0001%) in the national herd (USDA-APHIS, 2010). This MCI surveillance was supplemented by BMST of dairy herds. In states officially declared free of brucellosis, BMST was required two times per year in commercial dairies and four times per year in states not officially free of brucellosis. The development of this surveillance system was no small undertaking and required ample federal funding to maintain state and federal staffing at levels that would facilitate the cooperation and coordination of sample collection and testing. State-federal cooperative brucellosis laboratories in each state were staffed, equipped, and supplied to accomplish these goals. Annual reporting by states contributed to the information USDA-APHIS used to designate each state’s status.

USDA-APHIS began looking at changes to the National Brucellosis Surveillance program as more states achieved and maintained freedom from brucellosis. The agency recognized that the MCI and BMST surveillance systems may no longer be necessary, particularly as many states had been free of the disease for 5 or more years.

Nearly 5.3 million head of cattle were tested under the MCI in FY 2011. This included 4.1 million head tested at slaughter and 1.2 million tested at livestock markets (Carter, 2012). Changes were made to the national slaughter surveillance program beginning in 2011 consistent with the publication of the 2010 interim rule, including a reduction in sample collection at slaughter to approximately 3 million samples. Target sampling numbers were further reduced to 1 million samples in 2012 due to budgetary concerns (Carter, 2013). In FY2014, USDA-APHIS reported approximately 2 million samples collected at slaughter and 97,000 tested at livestock auction markets (Belfrage, 2015).

Only 10 slaughter plants across the nation now participate in sample collection for brucellosis surveillance (see Table 5-3). This level of surveillance is currently designed to detect brucellosis at a prevalence not to exceed 1 infected animal per 100,000 animals, with no disease detected or documented at that level (Belfrage, 2015). However, this surveillance system is not designed to detect brucellosis in animals leaving the DSA for slaughter. Each GYA state has a requirement for testing animals that leave the DSA for purposes of slaughter. The age at which animals are to be tested varies by state, from 12-18 months. Some variation also exists in the GYA state exemptions to testing DSA livestock leaving the DSA if they are destined for a livestock auction market, where it is assumed they will be tested prior to being sold to slaughter, which unfortunately is not always the case.

The 2010 interim rule requires states with a wildlife reservoir of B. abortus (in other words, the GYA states) to continue testing all adult cattle at slaughter, which includes adult cattle both within and outside of the DSAs. One of the flaws in this policy is that there are no major adult cattle slaughter plants in Wyoming or Montana, and there is only one slaughter plant in Idaho that is classified as a “top-40” plant by number of cows slaughtered in the United States.1 No major slaughter capacity for cattle exists in the GYA largely because of the distance from feed sources and feedyards.

Adult cattle that are culled from breeding herds are often transported from Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming to livestock auction markets in neighboring states where routine brucellosis testing is not conducted. Auction markets in South Dakota, for example, receive cull cows and bulls from Montana and Wyoming as they move from the rangelands of the west to feedyards near cornfields to the east and south. These cattle are identified with a backtag reflecting the state of the livestock market—not the state of origin—although traceability information is expected to be in place to allow tracing of an official identification device per the Animal Disease Traceability rule (2012/9CFR). These animals are no longer tested at the auction market and are delivered to slaughter plants across the country, most of which do not participate in the national slaughter surveillance program. This scenario creates a void of surveillance information that represents an at-risk population of cattle outside the boundaries of the DSAs.

5.2 Designated Surveillance Areas

The concept of zoning or regionalization for a disease is an effort to reduce the economic impact to the smallest, appropriate, and manageable geographic area. The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) recognizes this approach when considering trade implications related to disease status. Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming began using DSAs when USDA-APHIS drafted a paper outlining a concept for a new regulatory control approach (USDA-APHIS, 2009). As the 2010 interim rule was implemented, all three states developed DSAs based on past surveillance in wildlife as well as the locations of recent bovine cases of brucellosis.

___________________

1 Large slaughter establishments are responsible for a majority of the slaughter conducted in the United States. In addition, large slaughter establishments are almost universally specialized to process only one of two broad categories of cattle: fat cattle or culls. Fat cattle are generally young (under 36 months), while cull cattle are older cows and bulls that have been culled from the herd for various reproductive or performance-related reasons.

| Slaughter Plant by State | Estimated Number of Samples |

|---|---|

| California | 180,000 |

| Colorado (2 bison plants) | 26,000 |

| Minnesota | 138,000 |

| Nebraska | 410,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 115,000 |

| Texas (2 plants) | 438,000 |

| Utah | 75,000 |

| Wisconsin | 110,000 |

| TOTAL | 1,492,000 |

SOURCE: Herriott, 2017.

States in which a wildlife reservoir of B. abortus exists are required to describe and justify the boundaries of the DSA in a USDA-APHIS approved Brucellosis Management Plan (BMP). USDA-APHIS conducted a review of the three states’ BMPs for the first and only time in 2012. The reports generated from the reviews describe the strengths and weaknesses of each state’s implementation of its DSA and BMP, and they provide recommendations for improvement. Collectively, the reports also reflect the wide variation in how each state sets, monitors, and enforces DSAboundaries and regulations. Variation also exists in testing requirements for movement of livestock outside the DSA, exemptions for testing, timing of testing, and how state agencies permit movement and enforce DSA-related testing (USDA-APHIS, 2012). For example, all three states require testing of sexually intact “test eligible” cattle that change ownership or are moved from the DSA within 30 days of such an event. Yet Montana and Wyoming define test eligible cattle as 12 months and older, while Idaho defines the test eligible age as 18 months and older. Montana includes bulls in its definition of test eligible animals, while Idaho and Wyoming do not. Although bulls are not thought to spread brucellosis, it is an interesting surveillance finding that only infected bulls were identified as a result of DSA-related testing in 3 of the 10 cattle and domestic bison herds designated as infected in Montana between 2007 and 2016. Also, Idaho tests only animals that reside in the DSA anytime between January 1 and June 15 of the calendar year, while Wyoming waives the 30-day requirement if the test is conducted between August 1 and January 31, and Montana considers this same exemption for cattle tested between July 16 and February 15. All three states allow movement without testing to approved livestock auction markets, provided those markets will test eligible cattle upon arrival before sale.

Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming have each expanded their DSA boundaries at least once since the initial development of those boundaries. The most common reason for DSA expansion is finding seropositive elk outside the current DSA boundaries, although there are no uniform recommendations or requirements for states to adjust DSA boundaries based on seroprevalence of B. abortus in wildlife. Surveillance conducted by WGFD has identified seropositive elk outside the DSA each year from 2012-2015, yet the boundaries of the DSA have not been adjusted since the last USDA review in 2012. As previously noted, culled livestock leaving this area may or may not be subject to slaughter surveillance or testing at livestock auction markets. Lack of testing adult livestock from areas where seropositive wildlife have been identified may represent an unknown risk of disease transmission. Additional standardization of DSA designations and oversight of DSA surveillance and associated movement controls by USDA-APHIS may be warranted to prevent movement of potentially infected livestock outside high-risk areas. In addition, more frequent reviews of state BMPs by USDA-APHIS may ensure that the three states are uniformly adhering to their plans in accordance with national animal health program goals.

Seropositive elk have been found in some areas outside DSA boundaries. If adjustments are not accordingly made to the DSA boundaries in recognition of expanding seropositive wildlife, then cattle residing in those areas may not be subject to DSA testing requirements and early detection opportunities may be missed.

6. BISON SEPARATION AND QUARANTINE

Quarantining bison, followed by repeated test and removal of positive animals, is a viable tool for establishing brucellosis-free bison from infected bison populations. In December 2000, state and federal agencies involved in the management of YNP bison reached a record of decision to implement the IBMP for the purpose of managing bison that exit YNP into the state of Montana. In negotiations and hearings that were conducted to develop the IBMP, agencies were instructed to examine the feasibility of bison quarantine, with the intent of being able to certify bison as brucellosis free. There have also been frequent discussions regarding bison conservation strategies in North America and the potential for restoring the species to grassland ecosystems (Ryan Clarke et al., 2014). The agencies agreed that capturing and relocating bison to other suitable habitats would be an appropriate alternative to lethally removing bison that exceeded population objectives for YNP, as described in the IBMP. As a result, the USDA-APHIS Brucellosis Eradication Uniform Methods and Rules (UM&R) (USDA-APHIS, 2003) included a proposed quarantine protocol to ultimately qualify bison from YNP and the Grand Teton National Park as brucellosis free.

A study was conducted to determine whether the proposed UM&R protocol could be used to qualify animals originating from the YNP bison herd as free from brucellosis, including latent infections (Ryan Clarke et al., 2014). The study validated the quarantine protocol as outlined in the UM&R, and it demonstrated that it is feasible to take subadult seronegative bison from an infected bison population and qualify animals as free of brucellosis in less than 3 years (Ryan Clarke et al., 2014). Because the primary method of transmitting brucellosis in the YNP herd is through abortion and birthing events, removing bison at less than 1 year of age from the infected herd minimizes the field exposure of each animal to B. abortus (Ryan Clarke et al., 2014). Additional data were provided to indicate that a seropositive result is an accurate indicator of infection, supporting the approved testing protocol for older bison as outlined in the UM&R and demonstrating that collection of tissues and swab samples immediately after birth was essential to accurately determine that bison are not shedding B. abortus (Ryan Clarke et al., 2014). Thus, utilizing a separation and quarantine procedure to obtain brucellosis-free bison from the YNP herd provides a viable conservation measure to obtain genetically pure bison for repopulating other grassland ecosystems. While separation and quarantine could be used to safely remove bison from the YNP herd, the value of this approach for overall bison population control in YNP is limited by logistical challenges of separating and quarantining hundreds of animals annually.

7. COSTS OF PROGRAMS

Two key points underlying ongoing contention on brucellosis in the GYA are the direct monetary costs and combined benefits of brucellosis oriented programs by multiple parties operating in the GYA. Economic value estimates can vary greatly depending on the set of factors considered and the scope of the evaluation. For example, the economic value of wildlife is larger if including the entire country’s demand for tourism viewing. Similarly, the economic value of disease mitigation efforts that private livestock owners may undertake is larger if the entire nation’s livestock herd is considered rather than solely considering the herd residing within the GYA. No known study has comprehensively documented direct monetarycosts. Similarly, the committee is unaware of any systematic assessment of associated benefits and effectiveness of how existing programs mitigate brucellosis risks. To provide context, even if not all inclusive, this section includes estimates to document substantial expense to both private and public parties and highlights the lack of a more comprehensive assessment as a critical knowledge gap.

The national scope of bovine brucellosis concerns is clearly reflected by state, federal, and private eradication efforts exceeding $3.5 billion over the past 75 years (NRC, 1998; Ruckelshaus Institute of Environment and Natural Resources, 2010). The GYA is estimated to support roughly 450,000 cattle and calves2 that have the potential to come into contact with approximately 125,000 elk and 3,000 to 6,000 bison residing in the GYA (Schumaker et al., 2012). The populations of livestock and wildlife outside the GYA are also substantial. The magnitude of these populations is key to understanding the ongoing private and public costs of brucellosis mitigation efforts. Moreover, recognizing that DSAs in all three GYA states have expanded since 2010 reiterates the impact of these populations interacting across expanding geographic space (personal communication, D. Herriott, USDA-APHIS, 2015). The following sections provide examples of costs incurred in current mitigation efforts and programs in cattle and wildlife.

7.1 Cattle

Most livestock operations make decisions motivated by profit‐oriented goals. Even though risk reduction options are available to livestock producers, those options may not appear advantageous to producers or are only partially implemented because the costs borne by individual producers outweigh the potential benefits. This reflects the reality that private costs and benefits need to be taken into account when considering policies and procedures to address brucellosis.

Ongoing livestock producer costs include expenses associated with an array of brucellosis management activities, including fencing haystacks, modifying winter feeding practices, vaccinating and spaying, and ongoing herd testing (Schumaker et al., 2012). The annual costs of ranch-level brucellosis management efforts range from $200 to $18,000 per operation (Roberts, 2011). Increased production costs from required brucellosis testing may range from $1.50 to $11.50 per head, with an estimated 330,000 cattle in Wyoming tested in 2004 alone (Bittner, 2004). Given this, in 2004 the combined testing costs to Wyoming producers were estimated to total between $495,000 and $3.7 million per year (Ruckelshaus Institute of Environment and Natural Resources, 2010). Those estimates do not include the expenses incurred by the owner (i.e., gathering, sorting, and handling the cattle) or the potential loss of market opportunities. Moreover, the effectiveness of these efforts in reducing risks largely remains unknown (Schumaker et al., 2012).

Separate from ongoing testing and compliance expenses, the costs of implementing brucellosis prevention activities and expenses realized under quarantines for a single producer could be considerable. Schumaker and colleagues (2012) estimate that if a 400-head cow-calf operation was quarantined during the winter feeding season following contact with an infected herd, uncompensated costs incurred by the producer would be $2,000 to $8,000 (Schumaker et al., 2012). If this producer’s herd is positive for brucellosis, the uncompensated costs are estimated at $35,000 to $200,000.

Considering a representative cow/calf-long yearling operation in Wyoming, Roberts and colleagues (2012) provide estimates of annual expenses and the baseline level of risk reduction (effectiveness) needed for the operation to break even in implementing each brucellosis prevention activity (see Table 2-3 in Roberts et al., 2012). For most mitigation activities, even if mitigation resulted in complete risk reduction (e.g., 100% effectiveness), the private decision would remain to not adopt because implementation and maintenance costs are higher than the benefits of risk reduction (Roberts et al., 2012). This underlies the central aspects of private versus public considerations and economics of externalities.

While these estimates (Roberts et al., 2012; Schumaker et al., 2012) are valuable in understanding the economic situation faced by an individual operation, they do so in a status quo manner without consideration of broader social or whole-system effects. That is, the distinction between private break-even analyses and whole system or societal optimization is critical because individual break-even points are identified presuming no external cost-sharing or outside incentivizing of adoption. While it is critical to understand economic incentives of individual cattle producers (Pendell et al., 2010; Tonsor and Schroeder, 2015), it is also important to understand the aggregate impacts and the prospect for policies that reflect social outcomes

___________________

2 Data available on livestock numbers are aggregated to the county level by USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service to protect the confidentiality of livestock operations.

and hence alter individual incentives to adjust their behavior. This broader aggregate understanding remains a key knowledge gap in understanding the broader impacts of brucellosis.

At the state level, the Wyoming Livestock Board incurred more than $1 million in brucellosis expenses between July 2012 and June 2014 (personal communication, J. Logan, October 2015). While the state of Wyoming pays for required brucellosis testing of cattle, producers still incur expenses every time an animal is handled. The cost of working an animal through a chute is between $6 and $11 reflecting injury, equipment, labor, and animal shrink (personal communication, J. Logan, October 2015). Moreover, another expense is lost market access or price discounts by buyers of cattle originating from within DSAs (personal communication, J. Logan, October 2015). As the DSA expands, the total number of cattle suspect to these impacts grows as additional cattle operations become directly impacted.

There are a few documented cases of cow-calf operations switching to stocker operations to reduce brucellosis-related expenses. The limited number of enterprise changes largely reflects a view that such adjustments are not cost-effective or feasible given biological and market forces (personal communication, J. Logan, October 2015). This, however, reflects a situation where broader social evaluation of the optimal split between cow-calf and stocker has yet to be examined, nor has there been any consideration of policies that may encourage additional shifting away from cow-calf production.

While a large brucellosis outbreak would result in substantial economic costs, perhaps $100-$300 million, the small reduction in probability of an already low-frequency event make testing of all DSA-origin breeding cattle something that is not deemed a cost-effective brucellosis mitigation strategy (USDA-APHIS, 2014). These cost estimates—and hence the conclusion that testing of all DSA-origin breeding cattle is not cost-effective—may not capture all involved expenses such as the costs involved if an infected animal went initially undetected or the costs associated with risks of incubating heifers who may test negative until close to calving only to be erroneously exported from the GYA.

7.2 Wildlife

The annual expenses incurred by state and federal agencies toward elk feeding operations are worth noting. Under average conditions, the estimated annual feeding costs for the NER (7,500 elk for 79 feeding days) is $337,488 in 1999 dollars, with alfalfa pellets being the largest expense item (Smith, 2001). This also suggests that the cost of wintering one elk is about $56 (in 1999 dollars) per winter, with estimates ranging from $35 to $112. These expenses do not include fixed expenses such as administration, contracting, or monitoring of feeding programs, which likely are substantial (personal communication, E. Cole, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2015). For example, IDFG (2015) estimates that approximately $100,000 is spent annually in Idaho’s state elk brucellosis management plan, yet Idaho is home to significantly fewer elk than Wyoming.

7.3 Multi-Species, Federal Programs

Some federal program expenditures are allocated to individual states without a specific application to targeting cattle, elk, or bison. Cooperative agreements focused on brucellosis in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming have ranged from $1.26 million to $1.72 million per year over the past 6 years (personal communication, D. Herriott, USDA-APHIS, 2015). These federalfunds are used to cover expenses of maintaining DSAs in the three GYA states. More broadly, a very small portion of federal program expenditures are allocated to research, and most is spent focused on testing and surveillance. While the Agricultural Act of 2014 (better known as the 2014 Farm Bill) did authorize brucellosis as a priority area for research due to its classification as a zoonotic disease with a wildlife reservoir, funds have yet to be appropriated for this priority issue to date.

REFERENCES

Belfrage, J. 2015. National brucellosis program update. Pp. 165-166. Proceedings One Hundred and Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the U.S. Animal Health Association, October 16-22, 2014, Kansas City, MO. Available online at http://www.usaha.org/Portals/6/Proceedings/2014%20USAHA%20Proceedings%20web.pdf (accessed January 6, 2017).

Bittner, A. 2004 An Overview and the Economic Impacts Associated with Mandatory Brucellosis Testing in Wyoming Cattle. Wyoming Department of Administration and Information. Available online at http://eadiv.state.wy.us/specialreports/Brucellosis_report.pdf (accessed January 6, 2017).

BLM (Bureau of Land Management). 2016. Fact Sheet on BLM’s Management of Livestock Grazing. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. Available online at http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/grazing.html (accessed June 4, 2016).

Brunner, R.D., C.H. Colburn, C.M. Cromley, R. A. Klein, and E.A. Olson. 2002. Finding Common Ground: Governance and Natural Resources in the American West. New Haven, CT:Yale University Press.

Carter, M. 2012. Moving forward with the brucellosis eradication program. Pp. 180-182 in Proceedings One Hundred and Fifteenth Annual Meeting of the U.S. Animal Health Association, September 29-October 5, 2011, Buffalo, NY. Available online at http://www.usaha.org/Portals/6/Proceedings/USAHAProceedings-2011-115th.pdf (accessed January 6, 2017).

Carter, M. 2013. National brucellosis program update. Pp. 196-198 in Proceedings One Hundred and Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the U.S. Animal Health Association, October 18-24, 2012, Greensboro, NC. Available online at http://www.usaha.org/Portals/6/Proceedings/USAHAProceedings-2012-116th.pdf (accessed January 6, 2017).

Creech, T., P.C. Cross, B.M. Scurlock, E.J. Maichak, J.D. Rogerson, J.C. Henningsen, and S. Creel. 2012. Effects of low-density feeding on elk-fetus contact rates on Wyoming feedgrounds. Journal of Wildlife Management 76(5):877-886.

Enright, F.M 1990. The pathogenesis and pathobiology of Brucella infection in domestic animals. Pp. 301-320 in Animal Brucellosis. K. Nielsen, and J.R. Duncan, eds. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

FWS (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service). 2016a. FWS Fundamentals. Available online at http://www.fws.gov/info/pocketguide/fundamentals.html (accessed January 30, 2016).

FWS. 2016b. National Elk Refuge: About the Refuge. Available online at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/National_Elk_Refuge/about.html (accessed January 30, 2016).

FWS. 2016c. National Elk Refuge: Elk. Available online at http://www.fws.gov/nwrs/threecolumn.aspx?id=2147515027 (accessed January 30, 2016).

FWS. 2016d. National Elk Refuge: Bison. Available online at http://www.fws.gov/nwrs/threecolumn.aspx?id=2147515045 (accessed January 30, 2016).

Galey, F. 2015. Efforts by the Wyoming Brucellosis Coordination Teamand the Consortium for the Advancement of Brucellosis Science. Presentation at the Third Committee Meeting on Revisiting Brucellosis in the Greater Yellowstone Area, September 16, 2015, Jackson Lake Lodge, WY.

Glynn, M.K., and T.V. Lynn. 2008. Zoonosis update: Brucellosis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 233(6):900-908.

GYIBC (Greater Yellowstone Interagency Brucellosis Committee). 2005. GYIBC Annual Report. Available online at https://archive.org/details/gyibcannualrepor2005grea (accessed March 25, 2016).

Herriges, J.D., E.T. Thirne, S.L. Anderson, and H.A. Dawson. 1989. Vaccination of elk in Wyoming with reduced dose strain 19 Brucella: Controlled studies and ballistic implant field trials. Proceedings of the U.S. Animal Health Association 93:640-655.

Herriott, D. 2017. Updated information based on Presentation at the Third Committee Meeting on Revisiting Brucellosis in the Greater Yellowstone Area, September 15, 2015, Jackson Lake Lodge, WY.

IBMP (Interagency Bison Management Plan). 2016. Interagency Bison Management Plan. Available online at http://www.ibmp.info (accessed March 25, 2016).

IDFG (Idaho Department of Fish and Game). 2015. Idaho Fish and Game 2015 Strategic Plan. Available online at http://fishandgame.idaho.gov/public/about/?getPage=191 (accessed March 22, 2016).

IDFG. 2016. Fish and Game Mission Statement. Available online at http://fishandgame.idaho.gov/public/about/commission/?getPage=186 (accessed March 22, 2016).

Maichak, E.J., B.M. Scurlock, J.D. Rogerson, L.L. Meadows, A.E. Barbknecht, W.H. Edwards, and P.C. Cross. 2009. Effects of management, behavior, and scavenging on risk of brucellosis transmission in elk of western Wyoming. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 45(2):398-410.

Maichak, E.J., B.M. Scurlock, P.C. Cross, J.D. Rogerson, W.H. Edwards, B. Wise, S.G. Smith, and T.J. Kreeger. 2017. Assessment of a strain 19 brucellosis vaccination programin elk. Wildlife Society Bulletin 41:70-79.

MFWP (Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks). 2016a. Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks: About Us. Available online at http://fwp.mt.gov/doingBusiness/insideFwp/aboutUs.html (accessed March 22, 2016).

MFWP. 2016b. Montana Statewide Elk Management. Available online at http://fwp.mt.gov/fishAndWildlife/management/elk (accessed March 23, 2016).

NPS (National Park Service). 2016a. National Park Service: What We Do. Available online at http://www.nps.gov/aboutus/index.htm (accessed January 30, 2016).

NPS. 2016b. Yellowstone Center for Resources: Annual Reports—Yellowstone National Park. Available online at https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/management/ycrannual_report.htm (accessed March 25, 2016).

NRC (National Research Council). 1998. Brucellosis in the Greater Yellowstone Area. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

OMB (Office of Management and Budget). 2007. Report to Congress on the Costs and Benefits of Regulations and Unfunded Mandates on State, Local, and Tribal Entities. Available online at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/inforeg_regpol_reports_congress (accessed January 30, 2016).

Pendell, D.L., G.W. Brester, T.C. Schroeder, K.C. Dhuyvetter, and G.T. Tonsor. 2010. Animal identification and tracing in the United States. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 92(4):927-940.

Plumb, G., L. Babiuk, J. Mazet, S. Olsen, P.P. Pastoret, C. Rupprecht, and D. Slate. 2007. Vaccination in conservation medicine. Revuescientifique et technique (International Office of Epizootics) 26(1):229-241.

Ragan, V.E. 2002. The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) brucellosis eradication programin the United States. Veterinary Microbiology 90(1-4):11-18.

Rhyan, J.C., P. Nol, C. Quance, A. Gertonson, J. Belfrage, L. Harris, K. Straka, and S. Robbe-Austerman. 2013. Transmission of brucellosis from elk to cattle and bison, Greater Yellowstone area, U.S.A., 2002-2012. Emerging Infectious Diseases 19(12):1992-1995.

Roberts, T.W. 2011. Costs and Expected Benefits to Cattle Producers of Brucellosis Management Strategies in the Greater Yellowstone Area of Wyoming. M.S. Thesis, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY.

Roberts, T.W., D.E. Peck, and J.P. Ritten. 2012. Cattle producers’ economic incentives for preventing bovine brucellosis under uncertainty. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 107(3-4):187-203.

Roffe, T.J., L.C. Jones, K. Coffin, M.L. Drew, S.J. Sweeney, S.D. Hagius, P.H. Elzer, and D. Davis. 2004. Efficacy of single calfhood vaccination of elk with Brucella abortus strain 19. Journal of Wildlife Management 68(4):830-836.

Ruckelshaus Institute of Environment and Natural Resources. 2010. Fact Sheet on the Consortium for the Advancement of Brucellosis Science (CABS): A Scientific Synthesis to Inform Policy and Research, January 2010. Available online at http://www.emwh.org/issues/brucellosis/CABS/2010-revised-cabs-fact-sheet(1).pdf (accessed January 6, 2017).

Ryan Clarke, P., R.K. Frey, J.C. Rhyan, M.P. McCollum, P. Nol, and K. Aune. 2014. Feasibility of quarantine procedures for bison (Bison bison) calves from Yellowstone National Park for conservation of brucellosis-free bison. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association 244(5):588-591.

Schumaker, B.A., D.E. Peck, and M.E. Kauffman. 2012. Brucellosis in the Greater Yellowstone area: Disease management at the wildlife—livestock interface. Human—Wildlife Interactions 6(1):48-63.

Scurlock, B.M. 2015. Presentation at the Third Committee Meeting on Revisiting Brucellosis in the Greater Yellowstone Area, September 15, 2015, Jackson Lake Lodge, WY.

Scurlock, B.M., W.H. Edwards, T. Cornish, and L. Meadows. 2010. Using Test and Slaughter to Reduce Prevalence of Elk Attending Feedgrounds in the Pinedale Elk Herd Unit of Wyoming: Results of a 5-year Pilot Project. Available online at https://wgfd.wyo.gov/WGFD/media/content/PDF/Wildlife/TR_REPORT_2010_FINAL.pdf (accessed June 4, 2016).

Slate, D., T.P. Algeo, K.M. Nelson, R.B. Chipman, D. Donovan, J.D. Blanton, M. Niezgoda, and C.E. Rupprecht. 2009. Oral rabies vaccination in North America: Opportunities, complexities, and challenges. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 3(12):e549.

Smith, B.L. 2001. Winter feeding of elk in western North America. Journal of Wildlife Management 65(2):173-190.

Thorne, E.T., T.J. Kreeger, T.J. Walthall, and H.A. Dawson. 1981. Vaccination of elk with strain 19 Brucellaabortus. Proceedings of the U.S. Animal Health Association 85:359-374.

Tonsor, G.T., and T.C. Schroeder. 2015. Market impacts of E. Coli vaccination in U.S. Feedlot cattle. Agricultural and Food Economics 3:7.

U.S. Congress. 2007. Oversight Hearing Before the Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands of the Committee on Natural Resources, U.S. House of Representatives. Serial No. 110-7. March 20. Available online at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-110hhrg34137/html/CHRG-110hhrg34137.htm (accessed March 25, 2016).

USAHA (U.S. Animal Health Association). 2001. Pp. 122-123 in USAHA Proceedings from the One Hundred and Fifth Annual Meeting, November 1-8, 2001. Pat Campbell and Associates, Richmond, VA, and Thomson-Shore, Inc., Dexter, MI.

USDA-APHIS (U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service). 2003. Brucellosis Eradication: Uniform Methods and Rules. APHIS 91-45-013. Available online at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/brucellosis/downloads/umr_bovine_bruc.pdf (accessed June 4, 2016).

USDA-APHIS. 2009. A Concept Paper for a New Direction for the Bovine Brucellosis Program. Available online at https://www.avma.org/sites/default/files/resources/0912_concept_paper_for_bovine_br_program_aphis-20090006-0002.pdf (accessed June 4, 2016).

USDA-APHIS. 2010. National Brucellosis Surveillance Strategy, December, 2010. Available online at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/brucellosis/downloads/natl_bruc_surv_strategy.pdf (accessed June 4, 2016).

USDA-APHIS. 2012. Review of Montana’s Brucellosis Management Plan. Available online at https://liv.mt.gov/Portals/146/brucellosis/DSA/2012_MT_DSA_REVIEW.pdf (accessed November 16, 2020).

USDA-APHIS. 2014. Brucellosis Regionalization Risk Assessment Model: An Epidemiologic Model to Evaluate the Risk of B. abortus Infected Undetected Breeding Cattle Moving out of the Designated Surveillance Areas in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Fort Collins, CO: Center for Epidemiology and Animal Health. December 2014. 54 pp.

USDA-APHIS. 2015. About APHIS. Available online at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/banner/aboutaphis (accessed January 30, 2016).

USDOI/USDA (U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2000. Record of Decision for Final Environmental Impact Statement and Bison Management Plan for the State of Montana and Yellowstone National Park, December 20, 2000. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, and U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Available online at https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/management/upload/yellbisonrod.pdf (accessed January 4, 2017).

USFS (U.S. Forest Service). 2016. U.S. Forest Service: About the Agency. Available online at http://www.fs.fed.us/about-agency (accessed January 30, 2016).

WBCT (Wyoming Brucellosis Coordination Team). 2005. Wyoming Brucellosis Coordination Team Report & Recommendations. January 11. Available online at http://www.wyomingbrucellosis.com/_pdfs/brucellosisCoordReport.pdf (accessed June 14, 2016).

WGFD (Wyoming Game & Fish Department). 2016a. About the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Available online at https://wgfd.wyo.gov/About-Us/About-the-Department (accessed March 22, 2016).

WGFD. 2016b. Brucellosis Reports: Brucellosis Management Action Plans. Available online at https://wgfd.wyo.gov/Wildlife-in-Wyoming/More-Wildlife/Wildlife-Disease/Brucellosis/Brucellosis-Reports (accessed March 23, 2016).

Wyoming Livestock Board. 2016. Wyoming Livestock Board: Animal Health. Available online at https://wlsb.state.wy.us/public/animal-health (accessed March 22, 2016).