1

Introduction

Environmental stressors have an enormous impact on human health. Almost one-fourth of the global burden of disease may be attributed to environmental factors (Cohen et al. 2017), so improving our nation’s understanding of the effects of the environment on health and well-being is critical. Through environmental research, the health effects of lead in gasoline were discovered, and policies were then developed to prohibit its use as an additive (EPA 1997). Environmental research has identified susceptible groups within populations by distinguishing vulnerable life stages and genetic factors (Landrigan et al. 2002; EPA 2007). Environmental engineers have developed technologies to monitor and improve water quality in lakes and streams (Walsh et al. 2005), spurred improvements in energy-use efficiency (Boyd 2005), and encouraged reuse of waste (Witt 2003). Environmental epidemiologists have learned that environmental tobacco smoke is a human carcinogen (Sun et al. 2007). Environmental research has been the engine that has driven those landmark improvements and is necessary to protect future human and ecosystem health (NRC 2012).1

Environmental research can be both basic and applied and is conducted by government agencies, by the industrial sector, and in academic and other research organizations. In general, agencies with some regulatory authority—such as the US Department of Agriculture, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—tend to conduct more applied research, whose objective is to gain knowledge or understanding necessary for determining how a recognized need may be met. Basic research, which is conducted to gain a more complete knowledge or understanding of the fundamental aspects of phenomena without specific applications aimed at processes or products in mind, tends to be conducted by nonregulatory agencies, such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NSF 2013).

EPA research is unique in that it covers applied research in both human health and the environment. Research is vital for understanding mechanisms for

___________________

1 Publications after July 2015 are no longer referred to as National Research Council (NRC) due to the name change to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

protecting human health and the environment and is thus crucial to EPA’s mission, as numerous reports have stated emphatically (NRC 1997, 2000, 2008, 2012). EPA research is collaborative and cross-disciplinary and has been bolstered by strong ties to academic research institutions that represent many sectors of the scientific community (NRC 2012). One avenue used to encourage ties to other research institutions is EPA’s extramural research program. EPA has had both intramural and extramural research programs since its creation. In the early days, the extramural program was managed by its laboratories and other technical facilities around the nation (NRC 2014). The managers of EPA’s Office of Research and Development (ORD) laboratories controlled extensive extramural research resources. For example, the budget in 1981 for EPA extramural research was roughly $250 million (EPA 1980), equivalent to $655 million in 2016 dollars (BLS 2016). The extramural funds were so considerable in the early years of EPA because the growing US environmental agenda placed a heavy burden on ORD for research results. ORD struggled to respond, and laboratory managers relied heavily on contracts and cooperative agreements to meet its needs. The complex funding arrangements created problems related to the management of research and to ensuring that the work was responsive to the needs of the program offices (Johnson 1996; NRC 2003). There also was a general perception that laboratory managers had substantial local autonomy and control over funding decisions. There was little coherent or transparent policy for external peer review of proposals as commonly used in the scientific community (Johnson 1996; NRC 2003).

To respond to concerns about the complexity of the extramural program, Robert Huggett, assistant administrator of EPA for ORD, reorganized ORD and initiated the Science to Achieve Results (STAR) program in 1995. He reallocated $57 million in funds from other ORD-sponsored research efforts, primarily the “exploratory research” program (NRC 2003). The new STAR program was assigned to one of the ORD’s research centers, the National Center for Environmental Research and Quality Assurance, now the National Center for Environmental Research (NCER), which addressed the transparency concerns related to the previous program by creating standard procedures for peer review and awarding of grants. The program was designed to meet the long-term research needs of the nation through extramurally funded projects, centers, and fellowships (NRC 2003).

STAR is still managed by NCER. NCER’s portfolio now consists of such programs as Small Business Innovation Research contracts and other support initiatives, such as the undergraduate Greater Research Opportunities (GRO) fellowships; People, Prosperity and the Planet awards; other congressionally directed research grants and centers; and STAR. STAR is a competitive peer-reviewed research grants program that supports environmental research in academic and other nonprofit organizations. Until 2016, STAR provided graduate fellowships for master’s and PhD students and funding for research pertaining to human health and the environment. In 2015, it was decided that science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs and activities throughout the federal government should be consolidated in the 2016 budget; the

resources for the STAR fellowships were redirected to NSF (Johnson 2016; OSTP 2015).

FUNDING OF THE SCIENCE TO ACHIEVE RESULTS PROGRAM

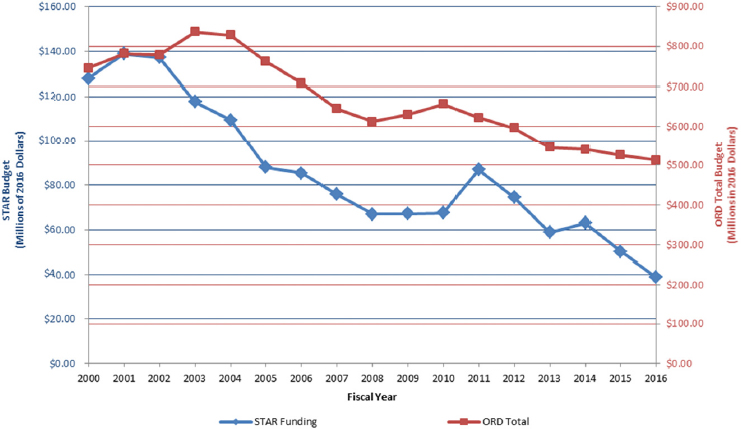

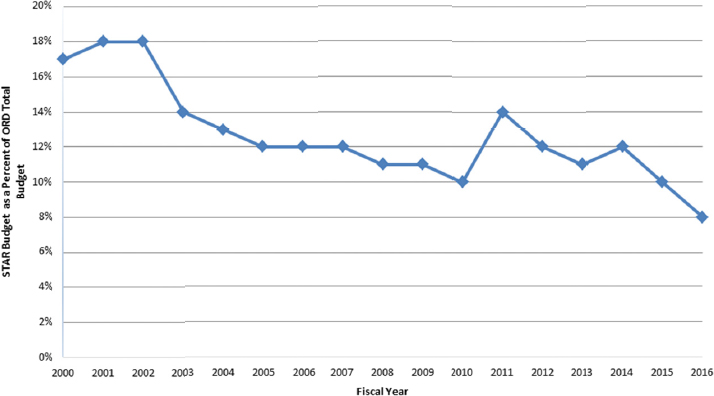

Funding for the STAR program has fluctuated, with a peak of around $138 million (2016 dollars) in 2001 and 2002, a median of $75 million (2016 dollars), and a minimum of $39 million in 2016 (see Figure 1-1). In 2000, the STAR program accounted for 17% of the total ORD budget (Figure 1-2). In the intervening years, the total budget for ORD fluctuated between $835 million (2016 dollars) in 2003 and $513 million in 2016, and the STAR program now accounts for about 8% of the total ORD budget (Johnson 2016).

THE COMPONENTS OF THE SCIENCE TO ACHIEVE RESULTS PROGRAM

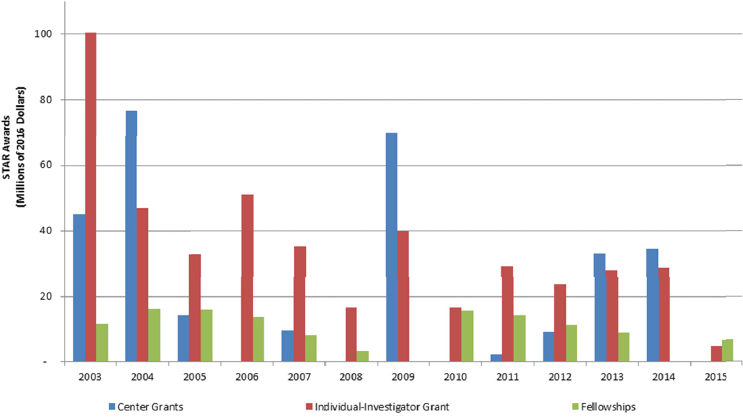

The components of STAR have also evolved. Exploratory grants awarded in response to general solicitations were an early part of the program, but there has been a shift toward more topically focused research questions embodied in requests for applications (RFAs) (NRC 2003). Now there are focused grants to individual investigators and larger center grants, and until 2016 there was a graduate fellowship program. Figure 1-3 displays the total award amounts by type from 2003 to 2015. Although awards are funded for multiple years, total award amounts in Figure 1-3 are assigned to the years of release of the funding announcements, so the total funds for each year do not match those in Figure 1-1. Individual-investigator grants have been awarded every year, but center grants and fellowships were not awarded yearly. In 2009 and 2014, no fellowships were awarded; and in 2006, 2010, and 2015, no center grants were awarded. Awards made in response to the 2015 RFAs were in progress during the preparation of the present report (EPA unpublished material, 2016).

Individual-Investigator Grants

Individual-investigator awards are smaller project-based grants that provide funding to individuals or small teams of investigators. The proposals are submitted by universities, colleges, and nonprofit research institutions. Awards are usually for 2-3 years and range from just over $65,000 to just over $1 million (2016 dollars). The number of individual-investigator grants awarded has varied by year. For example, only 25 were awarded in 2008 but 192 in 2006. In 2015, the single RFA was issued which drew 32 applications, of which six were selected for funding.

Center Grants

Center grants fund multidisciplinary efforts involving many investigators working in complementary fields. The multidisciplinary nature of the centers allows research programs to incorporate different fields of expertise to tackle complex problems. For example, chemists, exposure scientists, epidemiologists, pediatricians, and child-development specialists explore the effects of environmental exposures on children’s health and development. Often, several research organizations are involved in one center. Most center grants are funded for 5 years. The amount of an award varies, from less than $1 million to $10 million or more over 5 years; over half the center grants were for a total of over $4 million. No STAR center grants were awarded in 2015.

Fellowships

STAR graduate fellowships aimed to encourage promising students to pursue advanced degrees and careers in environment-related fields (NRC 2003). The number of fellowships awarded in 2003-2015 varied: 137 in 2010, zero in 2009 and 2014, and an overall average of 81 per year. In 2015, the fellowships provided up to $44,000 per year of support per fellowship. Master’s-level students may receive support for a maximum of 2 years (that is, a maximum of $88,000). Doctoral students could be supported for a maximum of 3 years (a maximum of $132,000); the support could be received during a period of 5 years.

The fellowships were intended to defray costs associated with advanced, environmentally oriented study leading to a master’s or doctoral degree. STAR fellowship applications could support the causes effects, extent, prevention, reduction, and elimination of all pollution across all media (air, water, soil) that adversely affect the environment and human health. The process for awarding of fellowships consisted of a peer review by non-EPA scientists and an internal

programmatic review by EPA scientists of applications that received a final score of excellent in the peer review. The internal programmatic review aimed to ensure that applications were related to the EPA mission and would contribute to an integrated, balanced research portfolio (EPA 2015a).

In the 2016 budget, funding for STAR fellowships was eliminated (OSTP 2015). The STAR fellowships had been the only federal fellowships designed exclusively for students pursuing advanced degrees in environmental sciences and had aimed to build cohorts of environmental scientists who had the multidisciplinary backgrounds needed for addressing complex environmental-science problems. To consider the effects of the loss of the STAR program on the training of environmental and environmental health scientists, the number of NSF fellows in 2015 when the STAR program was still active was compared with the number in 2017, after the STAR program was terminated. In 2015, NSF was supporting 168 fellows who were studying environmental sciences and engineering or ecology, and STAR was supporting 51 fellowships—a total of 219 total fellowships in environmental sciences (EPA 2015b, NSF 2017). In 2017, NSF awarded 176 fellowships in environmental sciences. Thus, after cancellation of funding of STAR fellowships, there were 43 fewer graduate fellowships in environmental and health sciences (NSF 2017).

Research Fields

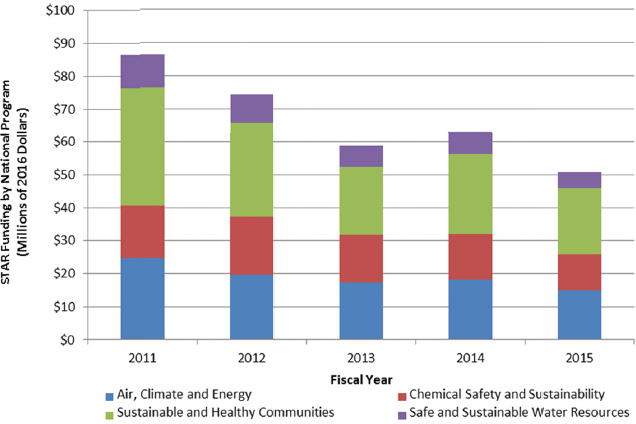

To see how STAR’s support of different fields evolved, the committee looked at the STAR budget related to ORD’s four national programs: Air, Climate, and Energy (ACE), Chemical Safety and Sustainability (CSS), Safe and Sustainable Water Resources (SSWR), and Sustainable and Healthy Communities (SHC). Figure 1-4 displays the STAR funding of each national program in FY 2011-2015. The portion of the STAR budget received by each program was similar for each of the 5 years. SHC receives the largest portion of the STAR budget, with an average of 38%, followed closely by ACE, with an average of 30%. CSS and SSWR received an average of 21% and 11%, respectively.

SUMMARY OF PREVIOUS REVIEWS OF THE SCIENCE TO ACHIEVE RESULTS PROGRAM

The STAR program has been reviewed many times since 2000. The reviews can be categorized as ones requested by EPA, ones that were part of EPA’s planning and review procedures, and ones that were completed for an audit or external review purposes. Some reviews have been broad, with recommendations that affect the entire ORD program, which encompasses STAR; they offered such recommendations as developing roadmaps and goals for ORD programs and emphasizing the inclusion of social, behavioral, and decision sciences. Others have been narrower, focusing on specific elements, such as STAR fellowships. A common recommendation of the programmatic reviews has been to emphasize the importance of improving communication, dissemination, and outreach of

STAR research results both in and outside EPA to other stakeholders. Some reviews have emphasized the importance of measuring the timeliness of the completion of grants and effectiveness.

The last scientific review of only the STAR program was the 2003 National Research Council review. It occurred after a 2000 request from EPA (NRC 2003). The reviewing committee analyzed information provided by EPA, STAR grant recipients and fellows, and other sources to assess the program’s scientific merit and public benefits. The 2003 committee strongly endorsed the STAR program as an integral part of EPA’s research program that provided the agency access to external and independent information, analyses, and perspectives. Box 1-1 summarizes the committee’s key findings.

Other scientific reviews that covered STAR include those of ORD’s research program by the EPA Board of Scientific Counselors (BOSC) and Science Advisory Board (EPA SAB/BOSC 2011, 2012; EPA BOSC 2016). The latter reviews were conducted as part of the planning and review procedures established in ORD. The STAR program was not the focus of the reviews, but the reports included recommendations that would affect it. For example, the most recent of the reviews included all ORD programs and thereby affected the STAR program. Suggestions include developing measures of success for outputs and outcomes of each program. The review also suggested that EPA further develop and enhance efforts in research synthesis and translation, continue to nurture and expand cross-program and transdisciplinary integration to increase efficiencies and synergies, and maintain alignment between research focused on short-term goals and research focused on long-term objectives.

The STAR program was audited recently by EPA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) (EPA 2016). The OIG report recommended that ORD identify the direct and incidental benefits of the STAR program. STAR was requested to have procedures in place for conducting and evaluating relevance reviews and for soliciting and considering input from program offices. OIG’s recommendations were based on an extensive survey of the ORD staff and management. The BOSC review had emphasized the need to be clear about the use of such key terms as partners, stakeholders, and end users at ORD. The report also encouraged ORD to foster greater cross-program and transdisciplinary integration. This review and others and EPA’s responses are summarized individually in Appendix B.

THE CURRENT REVIEW

The director of NCER approached the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology about conducting an independent assessment of the STAR program. To conduct the study, the Academies convened the Committee on the Review EPA’s Research Grants Program, which prepared the present report. The committee’s members were selected for expertise in toxicology, epidemiology, public health, exposure science, environmental science and engineering, ecology, sustainability, risk assessment, and research management and program evaluation. (See Appendix A for committee membership and biographies.) None of the committee members was a current recipient of a STAR grant, nor did any committee member apply for a STAR grant during the course of the study.

The committee was charged with conducting a program review of STAR. Its statement of task is provided in Box 1-2.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

Although the statement of task refers to the STAR competitive extramural grants program, the committee interpreted that to include the fellowship program because the fellowship program had been a long-standing integrated component of STAR. It evaluated the program as a whole and did not systematically evaluate the quality of individual research grants. It used the three components from the statement of task to guide its approach: assess the STAR program’s scientific merit, assess the program’s public benefits, and assess the program’s contribution to the nation’s important environmental research needs.

To assess whether STAR procedures sponsor research of high scientific merit the committee compared STAR’s operating procedures for determining topics for priority-setting, developing funding announcements, and the procedures for the review and award of grants with those of other extramural research programs that fund research in similar fields. The committee also read all STAR RFAs released from 2003 to 2015; each committee member read about seven RFAs.

To assess the program’s public benefits, the committee created a logic model. A logic model is a visual depiction of how a program is designed to achieve its goals (McLaughlin and Jordan 2015). In the case of STAR, the goals include only indirect benefits to EPA in that through the Federal Grants and Cooperative Agreement Act of 1977 grants cannot directly benefit federal agencies (Engel-Cox et al. 2008). Then the committee reviewed metrics for points along the model to consider the ability of the STAR program to achieve its goals.

To assess STAR’s contribution to the nation’s important environmental research needs, the committee first considered the landscape of environmental research and the specific scientific fields that are important for contributing to environmental knowledge and capacity and thus addressing environmental challenges. Then the committee contemplated how STAR contributes in a distinctive way.

The remainder of this report is organized into four chapters. Chapter 2 covers the assessment of the STAR program’s scientific merit, Chapter 3 the committee’s assessment of the STAR program’s public benefits, and Chapter 4 the committee’s assessment of STAR’s contribution to the nation’s important environmental research needs. Chapter 5 presents the committee’s findings and recommendations.

REFERENCES

BLS (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2016. Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator [online]. Available: https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm [accessed January 18, 2017].

Boyd, G.A. 2005. A method for measuring the efficiency gap between average and best practice energy use: The ENERGY STAR industrial energy performance indicator. J. Ind. Ecol. (3):51-65.

Cohen, A.J., M. Brauer, R. Burnett, H.R. Anderson, J. Frostad, K. Estep, K. Balakrishnan, B. Brunekreef, L. Dandona, R. Dandona, V. Feigin, G. Freedman, B. Hubbell, A. Jobling, H. Kan, L. Knibbs, Y. Liu, R. Martin, L. Morawska, C.A. Pope, III, H. Shin, K. Straif, G. Shaddick, M. Thomas, R. van Dingenen, A. van Donkelaar, T. Vos, C.J.L. Murray, and M.H. Forouzanfar. 2017. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: An analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389(10082):1907-1908.

Engel-Cox, J.A., B. Van Houten, J. Phelps, and S.W. Rose. 2008. Conceptual model of comprehensive research metrics for improved human health and environment. Environ. Health Perspect. 116 (5):583-592.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1980. ORD Extramural Program Guide FY 1981. EPA 600/9-80-052. Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. October 1980.

EPA. 1997. The Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act 1970 to 1990 [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/contsetc.pdf [accessed January 17, 2017].

EPA. 2007. A Decade of Children’s Environmental Health Research: Highlights from EPA’s Science to Achieve Results Program. EPA/600/S-07/038. Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-09/documents/decade-of-childrens-health-full-report.pdf [accessed January 17, 2017].

EPA. 2015a. Science to Achieve Results (STAR) Fellowships for Graduate Environmental Study Funding Opportunity Announcement. Office of Research and Development, National Center of Enviornmental Research, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC [online]. Available: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.rfatext/rfa_id/579 [accessed April 27, 2017].

EPA. 2015b. STAR Graduate Fellowships Request for Applications Closing Date: May 26, 2015 [online]. Available: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/recipients.display/rfa_id/579 [accessed January 18, 2017].

EPA. 2016. EPA Offices Are Aware of the Agency’s Science to Achieve Results Program, but Challenges Remain in Measuring and Internally Communicating Research Results That Advance the Agency’s Mission. Report No. 16-P-0125. Office of Inspector General, U.S. Environmental protection Agency, Washington, DC [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-03/documents/20160330-16-p-0125.pdf [accessed May 16, 2017].

EPA BOSC (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Board of Scientific Councilors). 2016. Review of EPA Office of Research and Development’s Research Programs. January 8, 2016 [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-03/documents/bosc_report_02-29-2016_final.pdf [accessed January 18, 2017].

EPA SAB/BOSC (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Science Advisory Board and the Board of Scientific Councilors). 2011. Office of Research and Development (ORD) New Strategic Research Directions. October 2011 [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-03/documents/stratresdir111021rpt.pdf [accessed January 18, 2017].

EPA SAB/BOSC. 2012. Implementation of ORD Strategic Research Plans. September 2012 [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-02/documents/120928rpt.pdf [accessed January 18, 2017].

Johnson, J. 1996. Rebuilding EPA science. Environ. Sci. Technol. 30(11):492A-497A.

Johnson, J. 2016. Presentation at the First Meeting on Review of EPA’s Science to Achieve Results’ Research Grants Program, June 21, 2016, Washington, DC.

McLaughlin, J.A., and G.B. Jordan. 2015. Using logic models. Pp. 62-87 in Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, 4th Ed., K.E. Newcomer, H.P. Hatry, and J.S. Wholey, eds. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Landrigan, P.J., C.B. Schechter, J.M. Lipton, M.C. Fahs, and J. Schwartz. 2002. Environmental pollutants and disease in American children: Estimates of morbidity, mortality, and costs for lead poisoning, asthma, cancer, and developmental disabilities. Environ. Health Perspect. 110(7):721-728.

NRC (National Research Council). 1997. Building a Foundation for Sound Environmental Decisions. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC. 2000. Strengthening Science at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC. 2003. The Measure of STAR: Review of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Science to Achieve Results (STAR) Research Grants Program. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2008. Evaluating Research Efficiency in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2012. Science for Environmental Protection: The Road Ahead. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2014. Rethinking the Components, Coordination, and Management of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Laboratories. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NSF (National Science Foundation). 2013. Federal Funds Survey Glossary. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/fedfunds/glossary/def.htm#basic [accessed January 18, 2017].

OSTP (Office of Science and Technology Policy). 2015. Progress Report on Coordinating Federal Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Education. Executive Office of the President of the United States, Washington, DC [online]. Available: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/stem_ed_budget_supplement_fy16-march-2015.pdf [accessed January 18, 2017].

Sun, S., J.H. Schiller, and A.F. Gazdar. 2007. Lung cancer in never smokers – A different disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7(10):778-790.

Walsh, C.J., T.D. Fletcher, and A.R. Ladson. 2005. Stream restoration in urban catchments through redesigning stormwater systems: Looking to the catchment to save the stream. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 24(3):690-705.

Witt, C.E. 2003. It makes sense because it makes cents. Mater. Handl. Manage. 58(3):14.