3

Case Example 1: Justice Reinvestment

The first contemporary case example from a non-health sector discussed at the workshop was in the area of justice reform and justice reinvestment.1 Elizabeth Lyon, the deputy director of state initiatives at the Council of State Governments Justice Center, provided an overview of the technical support provided to states that are participating in the Justice Reinvestment Initiative. Judge Steven Teske, the chief judge of the juvenile court of Clayton County, Georgia, spoke about how Clayton County, with leadership from the juvenile court, has created an infrastructure for both public and private funding to support evidence-based programs to reduce juvenile crime. He described a school–justice partnership model that is designed to reduce juvenile delinquency by promoting academic success using alternatives to suspensions and school-based arrests.

The session was moderated by Paula Lantz, the associate dean for academic affairs and a professor of public policy at the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. (Highlights are presented in Box 3-1.)

___________________

1 According to the Council of State Governments Justice Center, “[j]ustice reinvestment is a data-driven approach to improve public safety, reduce corrections and related criminal justice spending, and reinvest savings in strategies that can decrease crime and reduce recidivism.” See https://csgjusticecenter.org/jr (accessed July 25, 2018).

JUSTICE REINVESTMENT INITIATIVE

The Justice Reinvestment Initiative is a public–private partnership funded by the U.S. Department of Justice, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, and The Pew Charitable Trusts, Lyon said. The initiative was first federally funded in 2010, and about 30 states have participated in the program.

Rising correction costs are a significant concern for state leaders. Many states spend more on corrections than they do on education. In 2015 states were spending well over $57 billion on institutional corrections. A state facing rising correction costs or other criminal justice issues can apply to become part of the program. There is a fairly rigorous threshold that has to be met before a project is initiated, Lyon said. All three branches of government in the state must agree to participate, and there must be bipartisan support. The governor, the chief justice, the senate president, and the house speaker are required to sign letters indicating their support for participating in the project. The program is data driven and relies on information gathered from local government, state government, and

other sources. Data-sharing agreements are required so that a technical assistance provider can analyze the state data independently. There are several technical assistance providers, including the Council of State Governments Justice Center, the Crime & Justice Institute, the Pew Center on the States, and others. Over the course of 1 to 3 years, a unique problem statement is then developed for the state, identifying what is driving its corrections issues and its corrections costs. The process begins with an extensive stakeholder engagement process, which involves meeting with local government, law enforcement, behavioral health experts, treatment service providers, victim advocates, the business community, and others. The Justice Reinvestment Initiative then proposes policy solutions and changes that can be made to the corrections system to avert rising costs and produce safer outcomes for communities, and it helps implement and sustain data collection, performance metrics, transparency, and accountability. The stakeholder-engagement, analysis, and policy-development steps typically require around 1 year to complete, after which a legislative package is typically introduced. Lyon said that there is an excellent track record of legislation being passed in a short period of time, which she attributed to the high level of buy-in that happens before the process even starts. She added that criminal justice is an issue on which people can find common ground, and she identified fluency on the issue, relationships, policy, and buy-in as being among the many contributors to the success of this effort. After the policies are enacted, there is an implementation-support phase that lasts from 12 to 24 months.

There are many factors that drive individuals’ entry into the correctional system, and later, recidivism, Lyon said. These factors include social networks, neighborhood, home situation and housing, employment, an individual’s ability to respond when faced with a problem, and support systems. The challenge is to identify the approaches that can help individuals so that they do not return to the correctional system.

State Funding and Reinvestment Examples

State governments are seeking to avert rising correction costs so that they can address various other priorities in their state budgets. However, a system cannot be changed so comprehensively without making investments in that system. Creating a lasting change can take quite a few years. Implementation support, including justice reinvestment, helps to fund these programs.

Lyon shared several examples of how states have chosen to fund justice reinvestment programs and to reinvest the savings generated from successful policies. When the Justice Reinvestment Initiative was first getting started, the idea was to take the calculated savings from correc-

tions costs and invest them back into the community, into non-correction domains. An early project in Kansas was set up this way, but it was decided that there was so much need in the correctional system that the funding should stay within that system in order to address those needs.

Pennsylvania chose not to make an upfront investment in programs, but instead created a statutory formula that requires the legislature to calculate, on an annual basis, the savings attributed to justice reinvestment policies, and the state mandates that those savings be redirected into relevant programs. Because policies take time to actually realize savings, there was not much to be reinvested in programs in the first several years. However, during one fiscal year the savings attributed to the program grew from $12 million to $38 million, and based on the formula, the reinvestment went from $3 million to $10 million. That money was reinvested in victim services, risk assessment tools, policing, county probation, community reentry efforts, and other state parole efficiencies.

In contrast, Lyon said, West Virginia made an upfront investment, appropriating nearly $12 million over the course of 3 years to support expanded substance abuse treatment services. West Virginia has the highest rate of death per accidental drug overdose. In getting stakeholder input from judges, it seemed that the judges were sending drug offenders to jail as an alternative to putting them back on the streets, where the judges feared they would overdose and die. The state appropriations were used to establish a grant program for substance abuse treatment services for individuals at home in their communities. In order to be eligible for a grant, applicants were required to establish a partnership among the criminal justice service providers, the behavioral health service providers, and the community service providers, and to have a place to provide the treatment. Training was provided for the grant recipients because many behavioral health treatment providers had not previously worked with individuals who also had criminogenic needs (i.e., risk factors for recidivism) to be addressed. Lyon stated that research shows that it is not enough to treat just the substance abuse or just the thoughts that lead an individual to commit a crime; both need to be treated at the same time, as co-occurring issues.

In some programs, reinvestment is being made in community supervision. Research has shown that individuals who are in the community tend to do better than individuals who are behind bars. The challenge is to make community supervision more effective, not just to keep the individual from being re-incarcerated, but to keep the community safe as well (both the community where that individual may reside and the communities where that individual may go to commit crimes).

Lyon closed by mentioning that the initiative is currently being independently evaluated in order to understand the impact of the policies

enacted, and a report was published in early 2017. Early findings show that there has been a significant amount of money reallocated into different services to produce different outcomes, including decreasing prison populations and decreasing crime rates (in many places and across many categories).

IMPROVING OUTCOMES AND CONTAINING COSTS USING EVIDENCE-BASED PROGRAMS TO REDUCE JUVENILE CRIME

An analysis by the Georgia Criminal Justice Reform Council in 2012 found that when juvenile judges commit a child to state custody, it costs $91,000 per year to house a child in secure detention and about $29,000 per year to house a child in a non-secure facility. Teske, a member of the council, said that the analysis also found that 65 percent of these individuals reoffended within 3 years of their release from either a secure or a non-secure facility. In many cases, they had in the meantime reached the age of 17, the adult age of criminal liability in Georgia, and were now incarcerated in adult facilities. This is not the most effective use of taxpayer’s money, Teske said. He also pointed out that although about 35 percent of the population in Georgia is African American, nearly 70 percent of the youth who are “out-of-home” and committed to the state are children of color.

Current research indisputably shows, Teske said, that detaining low-risk youth or allowing low-risk youth to come in to the system has a significant negative impact on young people and increases the risk of delinquency. The analysis by the Georgia Criminal Justice Reform Council found that about 40 percent of the youth in secure confinement were low-risk offenders, and about 54 percent of the youth in non-secure facilities were low risk. Teske suggested that these were young people who probably would have outgrown their youthful delinquency, and instead they were indoctrinated into criminal culture in adult life.

Based on these findings, significant reforms were made to the state juvenile justice system in 2013. First, a judge can no longer commit a juvenile to an out-of-home placement for a misdemeanor offense, unless there are three prior separate adjudicated acts, of which at least one has to be a felony. This change alone will drive down the detained youth population in terms of bed space and also save money, Teske said. Changes to the system also included mandated use of validated risk assessment tools, including a detention assessment instrument, a pre-disposition risk assessment, a structured disposition matrix, and a juvenile needs assessment. In essence, judges cannot commit a child to the state unless that child has been assessed for risk and needs. Services for lower-risk youth will be provided in the community.

A structure for reinvestment was also created. Savings are placed with the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, and the use of the funding is overseen by a multidisciplinary group called the Juvenile Justice Funding Committee, which establishes the policies for how that money will be reallocated to local control. Funding is offered to counties through grants for community-based services for delinquent youth. Savings must be invested in evidence-based programs and practices that reduce recidivism in a juvenile population, Teske said. Programs shown to be effective interventions in this population include Multi-Systemic Therapy, Functional Family Therapy, Thinking for a Change, Aggression Replacement Training, and Seven Challenges. Teske said that none of these programs existed in the State of Georgia before the reforms because all resources were invested in brick-and-mortar facilities. Brick-and-mortar facilities punish the symptoms, he said, but do not treat the underlying causes of disruptive behavior and delinquency.

The results of the changes have been positive. In fiscal years 2014 and 2015, out-of-home placements were reduced significantly. With the shift to community-based rehabilitation, Georgia has been able to close three juvenile detention facilities, Teske said. In Clayton County, the savings available for reinvestment in evidence-based programs for youth increased from about $200,000 in 2014 to about $400,000 in 2015 and 2016, and about $700,000 was available for reinvestment in 2017.

School–Justice Partnership Model

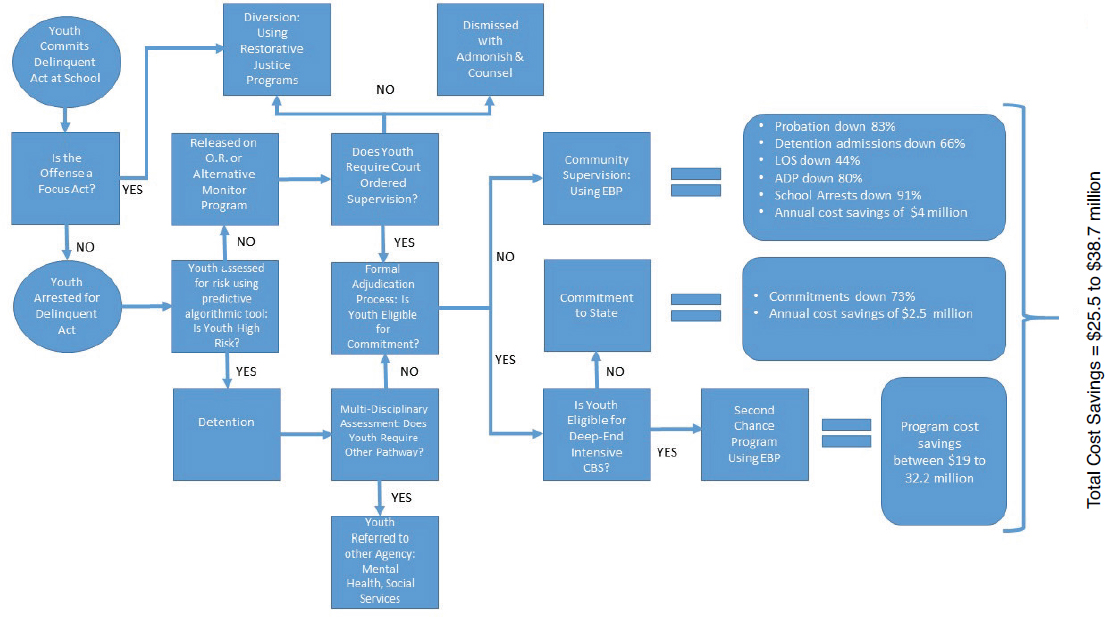

Teske described an algorithm to reduce recidivism in juvenile justice (see Figure 3-1). The algorithm is used when a youth commits a delinquent act at school. Misdemeanors never enter the court system, but rather are diverted to restorative justice programs. For those offenses for which a juvenile is arrested, there are “release valves” throughout the algorithm, and every opportunity is taken to move the juvenile off the delinquency pathway into a pathway that strategically addresses the underlying causes of the delinquent act he or she committed. For juveniles who are eligible for commitment, there is a “deep end” program called Second Chance.

Teske described expanding the algorithm to include the concept of prevention, incorporating mechanisms and tools to identify youth at risk, and to deliver targeted strategic services in a school–justice partnership model. This approach grew out of an epidemiology approach to juvenile justice. Like diseases, disruptive behaviors do not occur by chance, and they are not randomly distributed, Teske said. There are at-risk populations—and characteristics that place members of these populations at risk—that need to be studied so that solutions can be developed. The

NOTE: ADV = average daily population; CBS = community-based service; EBP = evidence-based practice; LOS = length of stay; O.R. = own recognizance.

SOURCE: Teske presentation, October 19, 2016.

goal of the partnership with the school system was to reduce suspensions and arrests. Research shows that keeping youth in school increases graduation rates, and increased graduation rates are associated with reduced crime. Since implementation of the program in Clayton County 2003, school arrests are down 91 percent, and graduation rates have risen every year. Arrests have been replaced with restorative justice practices (e.g., peace circles, mediation, drug testing, drug assessment, boundaries, drug education). All misdemeanors are prohibited from being referred to the juvenile court, including possession of drugs. The school system, through its school resource officers, can directly refer youth to the restorative justice division at the court without having them arrested and at no cost to the school system.

System of Care

Teske said that these alternatives do not necessarily work for chronically disruptive children. In 2010 the Clayton County System of Care was established to assist disruptive youth who are in need of clinical services, rather than education-based alternatives. The System of Care, a 501(c)(3) organization with both public and private funding, has a single point of entry called the Clayton County Collaborative Child Study Team. Every week the team visits all of the schools across the county and conducts risk–needs assessments of students and their families, looking to identify the underlying causes of the chronic disruptive behavior. Teske said that the number one cause of referral to the System of Care is trauma. Eighty-seven percent of referred students score high for trauma, most of which is associated with poverty. Students in the System of Care have shown improved attendance and improved grades in language arts, math, and science, and there has been an 86 percent decline in disciplinary referrals among this population. The first cohort is graduating from high school, and Teske said that these are students who would likely not have graduated at all. He added that the school board has now given $400,000 to the System of Care for direct services to chronically disruptive students because it reduces the school system’s administrative costs.

Clayton County from 2003 to Present

Teske shared some of the outcomes of Clayton County’s efforts since becoming a Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative site in 2003. The juvenile crime rate is down 71 percent, he said. Annual detention admissions have declined by 66 percent, and recidivism has declined. The average length of stay for juveniles who are detained has been reduced by

44 percent. The average daily detained population has been reduced by 80 percent. There has also been an 83 percent decline in the number of probationers; a 78 percent decline in total violations filed; and a 93 percent decline in violations of probation warrants. There has been a 73 percent decline in commitments to the state juvenile justice system (youth being placed out-of-home outside of Clayton County). Teske emphasized the importance of school climate and relationships in achieving these outcomes.

Core Strategies

In closing, Teske described some core strategies and lessons learned at the local level that he said also apply at the state level:

- Have a champion who has the characteristics of a convener—someone with vision, legitimacy, stakeholder knowledge, and subject-matter knowledge. For justice reform in Georgia at the state level it was the governor, and at the local level, Teske said it was he himself (as chief judge of the juvenile court) and the school superintendent.

- Use the research to determine what works in the subject-matter area.

- Using the best evidence-based practices, create a systemic algorithm. Determine where which practices will function best, so that they lead to cost savings.

- Use an incremental approach. Change must be made before savings can be realized and reinvested toward the identified best practices and programs. There may be a need to “invest to reinvest,” Teske said. In Georgia, the governor asked the legislature for an investment of $5 million to support evidence-based programs in the highest detention-committing counties. There needed to be programs available up front for the youth staying in the community rather than being committed to the state.

- Quality control mechanisms are needed as well as oversight of implementation. Failure to do this, Teske said, is the one thing that will kill reinvestment. Keep assessing and modifying.

- Develop a sustainability plan. For Georgia, it was the statutory creation of the Criminal Justice Reform Council.

- Good public relations are essential to fostering political will. Keep the issue in front of legislators, bureaucrats, and administrators and show them how using evidence-based practices saves money that can be strategically invested to improve outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Overcoming Challenges

Moderator Lantz asked the panelists about concerns they have dealt with in justice reform and reinvestment. For example, when closing facilities, there are likely to be concerns about job loss in the community. Teske acknowledged that there was some pushback at the local level, but he said he felt he was able to reduce it by approaching the changes in a collaborative way. He emphasized the importance of engaging stakeholders, and he said that a unified stakeholder approach was used. It is a consensus approach (i.e., not a majority vote) that allows for compromise, and it includes both voting members and advisors. Advisors are highly influential, he said, and include, for example, the Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia, the Public Defenders’ Council of Georgia, and the local county commissioners’ association. Any recommendations to the governor must be supported by research and data. Recommendations based in evidence and approaches that saved money were what won over the Republican-led legislature and led to culture change, he explained. He added that polling by Pew and others show that people favor rehabilitation and community-based programs over sending juveniles to prison.

On the topic of overcoming concerns, Lyon agreed with Teske’s core strategy of having champions. She suggested that a very deep bench of champions is needed when one’s champions are elected leaders who come and go. Lyon noted that different stakeholder groups will have different issues and said that this is where having a deep bench of champions can be helpful to allow for peer-to-peer interaction. As an example, she said, if a prosecutor is against something, a champion who is a prosecutor from a similar state could be enlisted to talk with that person, supporting the discussion with data. She acknowledged that sometimes the data are not enough or people do not believe the data. The strategy then is to keep discussing it, from different angles, across focus groups and meetings.

Lyon raised the serious concern of those occasions when an offender is released to community supervision and then commits a heinous crime. It becomes challenging to have conversations about data, because no matter how good the numbers are, someone has been killed in that community. Teske added that the Second Chance program is a highly intensive program based on best practices. More than 70 youth have graduated since 2010, with a 6 percent recidivist rate (one of whom did commit murder). If those 70 youth were sent to prison, Teske said, 65 percent of them would have reoffended when they were released. It is important to understand the overall risk, and there is a greater risk if these juveniles are sent to prison (which leads to, as noted, a 65 percent recidivism rate).

There are no perfect practices. It is about reducing the risk. But when that risk is realized, do not sensationalize it, he advised.

A Role for Health in Justice Reinvestment

Sanne Magnan asked how the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, public health, and health care systems could be helpful to justice reinvestment. Lyon suggested several areas where health could work with justice to help overcome challenges. A particular obstacle in rolling out funding for increased substance abuse services has been finding treatment providers who are willing to work with people in the criminal justice system. Another challenge is providing access to services, as many of the areas where the Justice Reinvestment Initiative works are very remote. The evidence indicates that individuals do best when they are in their communities, but this is challenging if those communities do not have services. A variety of approaches are being piloted, she said, including telemedicine. A related challenge is that many adults who leave the justice system are now taking medications to help address whatever recurring issues they might be dealing with. It would be helpful if state systems would provide a prescription that lasts more than 30 days. Lyon mentioned attempts to leverage Medicaid expansion to access these services, but said there are often not enough doctors to fill these prescriptions. When an inmate is released to supervision in the community, the first 60-day period is when that inmate is most likely to reoffend. It is during this time that closely coordinated care, services, and programs are essential, but these are some of the biggest challenges that states face.

Establishing the Evidence Base

Marthe Gold, a visiting scholar at The New York Academy of Medicine, acknowledged the role of an evidence base in making a persuasive case for a program, and she pointed to the lack of funding for such research. She asked about the quality and robustness of the evidence for justice programs and about who funds the research. Lyon said that federal resources supported some of the research on these programs. Legislation often mandates that funding can only be used for evidence-based programs, and it is a difficult conversation to have when a corrections director, governor, legislator, appropriator, or other stakeholder believes a particular program works, when the evidence shows otherwise. For adults, she said, there are actually few programs that have shown significant results in reducing recidivism.

Teske referred participants to the website of the Office of Juvenile Justice Delinquency Prevention (www.communitysolutions.gov). The website lists programs that are evidence based, programs that are prom-

ising, and programs that are known to not be effective. The questions are What does it take to move a program from promising to evidence-based? Where does the funding come from to support the research? In Georgia, there have been discussions about the potential need to relax the evidence base and to deploy some promising programs for the purpose of study.

Engaging Families

Magnan asked about engaging clients and their families in such a way that they do not feel disempowered by the new system that has been put upon them. Teske observed that many of these families do not want any intervention because they do not understand. They live a lifestyle that is normal to them, and they do not realize the trauma they are exposed to. Providers need to understand the responsivity principle of programming. This means that providers need to ensure that staff have the skills needed to be patient and to positively influence that family so they are receptive. With juvenile offenders there is also the possibility of having to deal with parents who themselves have mental health issues that are not being treated.

Mary Pittman, the president and chief executive officer of the Public Health Institute, asked about preventive interventions that could dissuade others in a family from following the same path as the disruptive or chronically disruptive youth in the family. Teske highlighted Multi-Systemic Therapy and Functional Family Therapy as important approaches. Clinicians go into the family home, identify all the issues that members of the family are facing (including basic needs such as food, shelter, transportation), and develop a treatment plan for the entire family. Teske said that court officers are reporting that families are happier after such interventions because they are seeing tangible results right from the beginning. Teske pointed out that the clinician is not solving the family’s problems, but is instead teaching the family members and empowering them to find solutions to their issues. The System of Care expands this approach to involve the community. Lyon added that there are different programs for adult offenders. She stressed the importance of talking directly to individuals who have been incarcerated, to those who are on community supervision, and to their families about what they need and what works. Lantz referred participants to a recently published cost–benefit analysis of Multi-Systemic Therapy and the cost savings it has shown (Borduin and Dopp, 2015; see also Dopp et al., 2014).