5

Realigning Resources for Population Health: Small Group Conversations

Following the panel discussions of the case studies, participants broke into small groups to discuss potential strategies to restructure, realign, and reallocate resources for population health that borrow from successful examples in other sectors and industries. Bobby Milstein, director at ReThink Health, set the context for the breakout discussions with a brief overview of financing structures and well-known examples. After the small group discussions, the workshop reconvened, and facilitators reported on their groups’ deliberations. (Highlights are presented in Box 5-1.)

SETTING THE CONTEXT FOR DISCUSSION

The cases presented at the workshop thus far have been stories of economic transition, Milstein said. The prison industrial complex in the United States has generated mass incarceration and manifest waste in both human and economic terms, he said. The examples discussed showed how investment and reinvestment can lead to very different sets of results for offenders and communities. Similarly, in the energy sector, Milstein added, the petro-industrial complex causes some harm, and efforts are under way to transition to greener, more efficient energy.

The challenge for population health is how to effect an economic transition and an “industrial revolution” in the way that health care is structured and financed that results in better population health, greater health equity, and greater development of human potential. Milstein reiterated the point by Rogers that anything of value can be financed. The challenge

is not just to promote evidence-based population health approaches, but to also define strategies for how to pay for them, with the mindset that financing should not be a constraint at the outset. How, with the assistance of financing experts and by taking lessons from other industries that have restructured to achieve similar co-benefits, can greater value and efficiencies be gained through focused innovations that improve population health?

Milstein acknowledged that the presentations only scratched the surface of how justice reinvestment actually works financially and only modestly explored the nuances of inclusive financing in the energy arena. However, even such high-level case examples demonstrate that there is an array of innovative financing options. The examples can thus foster a discussion about how to bring clarity to the action agenda for population health and how to define both the institutional arrangements and sources of money that could bring that agenda to fruition.

Menu of Financing Structures

To facilitate the group discussions, Milstein summarized potential financing structures for population health and classified them into 10

TABLE 5-1 Menu of Financing Structures (in order of relative dependability)

| Structures | Selected Examples |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTE: ACO = accountable care organization; BUILD = Bold, Upstream, Integrated, Local, Data-driven; CVS = CVS Pharmacy; MACRA = Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015.

SOURCE: Milstein presentation, October 19, 2016.

main categories (roughly ordered by relative dependability), providing selected examples in each category (see Table 5-1). He reminded participants that Internet links to further information about these and additional financing examples were provided in the background materials for the workshop.1 Milstein noted that part of the mission of the roundtable is to discuss what is needed to assure dependable resources for population

___________________

1 The workshop attendee packet is available at http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/PublicHealth/PopulationHealthImprovementRT/16OCT-19/Attendee%20Packet.pdf (accessed July 25, 2018).

health, and he observed that the vast majority of initiatives undertaken by multi-sector stakeholder collaboratives to advance their agendas are based on short-term, fragile financing.

Grants, Contracts, Donations, and Prizes

Most population health initiatives are funded by grants, contracts, donations, and prizes. Milstein highlighted multi-philanthropic initiatives, such as the Convergence Partnership and the BUILD Health Challenge, which he said are demonstrating pioneering ways of pooling philanthropic money for much longer-term and more profound types of investments.2

In-Kind or Barter Agreements

Another financing structure is in-kind or barter agreements. These can sometimes be more durable than short-term grants, as people see themselves as being in business with one another. As an example, Milstein highlighted the cross-jurisdiction sharing agreements that are negotiated among multiple regional health departments. These operating agreements help to deliver economies of scale, with the partners providing in-kind contributions. These agreements sometimes lead to more formalized or contracted arrangements as well. Milstein said that this financing structure has real economic force to it, but it can be difficult to count.

Hospital Community Benefit

Milstein acknowledged the ongoing conversation around hospital community benefit and the actual value to the public of programs that stem from the tax break that nonprofit hospitals receive. He referred participants to analyses by roundtable co-chair David Kindig and colleagues on the size of that value (Rosenbaum et al., 2015). The field is changing rapidly, Milstein said, pointing specifically to some modest expansions of investments in community health improvement and community building from nonprofit hospital sectors.

Health Care Payment Reform

Health care payment reform is bringing a shift from fee-for-service, volume-based payments to a system of payments based on value and

___________________

2 For more information on these examples, see http://www.convergencepartnership.org (accessed January 30, 2018) and http://buildhealthchallenge.org (accessed July 25, 2018).

quality. As examples, Milstein noted MACRA and the concept of global payments to health care providers. The regulatory framework around payment reform is a significant economic incentive that Milstein said could signal the need for other types of investments to flow differently.

Loans and Investments

There are numerous examples of loans and investments as financing structures that could be applied to population health. In the banking sector, the Community Reinvestment Act allowed for new ways of lending to occur. Milstein said that the community development and health sectors are frequently coming together to achieve co-benefits, and an equity agenda for investment is much more prominent. There is also a growing field centered on the pay-for-success approach to funding and another on impact investment (including explicit consideration of divesting from harms, such as oil or tobacco).

Dues, Earnings, and Legal Settlements

Milstein spotlighted dues, earnings, and legal settlements as a class of financing that often goes unnoticed. These funding sources are particularly important for multi-sector collaboratives. Famous and well-funded examples include tobacco settlements and the BP Deepwater Horizon settlements. Milstein mentioned the Public Health Institute in California, which has a program that invests legal settlement funds to improve public health and seeks public discourse about how the funds should be invested.3

Gain Sharing Agreements

The case examples of justice reinvestment and clean energy funding that were discussed at the workshop were concentrated on a class of financing structures that are essentially about gain sharing, Milstein explained. These agreements recognize co-benefits and are predicated on the idea that investments can deliver yield and that yield, in turn, can be strategically applied as the next new investment in something else.

Milstein said that the development of accountable care organizations (ACOs) and accountable communities of health raised questions about who should share in the savings that result from the redesign of the health care delivery system. The field is beginning to experience expansions in

___________________

3 For more information see http://www.phi.org/focus-areas/?program=public-health-trust (accessed July 25, 2018).

both the number of parties who are working to lower the total cost of care in a region and the scope of investments and reinvestments that are made over time.

Taxes, Credits, Trusts, Payments, and Mandates

Another category of funding is associated with the functions of government, including taxes and tax credits, as well as various appropriations and mandates. As examples, Milstein mentioned the so-called sin taxes on gambling, alcohol, tobacco, sugar, and now carbon emissions. He said that funds acquired through the carbon cap and trade system will likely be invested in initiatives that help people and the planet, and he suggested that public health professionals should consider whether they are truly prepared to help prioritize how funding from this program could be invested in population health. He reiterated the point made by Debbie Chang in the opening session regarding the potential of existing financing structures. Tried and true mechanisms (e.g., tax credits, low-income housing tax credits, and enterprise zones) are not being used as fully or as strategically as possible, he said.

Another mechanism in this category is wellness trusts, Milstein said, although he acknowledged that these are evolving with regard to management. He explained that the first-generation wellness trusts were funded by taxes on health care expenditures; however, the new generation of wellness funds associated with accountable communities for health are nongovernmental.

Community Wealth Building

One important aspect of community wealth building recognizes that institutions have a more significant impact on the economic life of their communities than just the services they provide. Anchor institutions (such as hospitals, universities, foundations, government, and others) also have a significant role and a long-term economic stake in the success of the communities in which they do business. Kaiser Permanente, for example, has incorporated a “total health impact” approach into its mission and its investing strategy. Employee ownership is another example of an approach that gives people in the community a much greater stake in the local economy. Milstein suggested that a local living economy that works economically likely also supports health and equity.

Commercial Market

Finally, the business models of institutions can have a role in financing population health. There are many examples of businesses adapting to the changing world and redesigning what they do, what they sell, who they sell it to, or at what price. As an example, Milstein pointed to CVS Pharmacy’s unilateral decision to stop selling tobacco.

In summary, there are at least 10 categories in which financial innovation is flourishing, Milstein concluded. The question is, how can these resources be strategically directed so that they yield multi-sector co-benefits and deliver opportunities for health, equity, and regional economic prosperity?

DISCUSSION

Participants raised several additional points to supplement Milstein’s overview. Flores observed that in many cases, spending is poorly tracked. A better understanding of where money is spent could help to enable trades, barters, and other agreements across different parts of government. Milstein agreed and emphasized the importance of transparent accounting in identifying opportunities for investments that yield co-benefits. He added that ACOs are recognizing that the insurance and health care delivery functions of the business are not actually disconnected and that, for example, changes in care delivery can lower the cost to the insurer. If care can be delivered more cheaply and the resulting savings invested more effectively in population health and well-being, the result will be a virtuous cycle and increased capital.

Isham suggested that the actor that employs the financing structure is a critical element. Milstein agreed that who the parties are in these kinds of arrangements is important. When arrangements work well, it is often because the parties see some synergy in their efforts. The solutions that lead to a more interdependent health economy are often those where the parties see the potential to generate greater value together than alone, he said. Isham referred participants to the Institute of Medicine report For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future, which considered mechanisms for funding governmental public health (IOM, 2012).

Magnan raised the issue of waste reduction as a financing mechanism. Milstein said that the two principal sources of economic benefit are generating value and eliminating waste. To some degree, any investment could deliver one or both benefits. There are many grant programs that are designed to achieve greater efficiency but do not address what happens when that efficiency is achieved (i.e., what to do with the savings). Magnan lamented that most journal articles that describe a cost savings

as a result provide no information about the next step, that is, what was done with the savings and who got to decide. Milstein also emphasized the need for benchmarks for investments in the population health agenda and multi-sector goals (Kindig, 2015).

Bridget Kelly, the co-founder and chief delivery officer of Bridging Health and Communities, asked where inclusive financing fits into the strategies listed, given that those with the most limited resources and in the poorest health also tend to have very little voice in the financing process. Milstein responded that any one of these strategies could be done with greater or less democratic integrity and that the principle of inclusive financing could be implemented across the menu. One could, for example, implement a grant program or negotiate a gain-sharing agreement through community co-design. It is challenging, he added, because health care cost savings are a reflection of a large cast of actors who have to cooperate in order to realize results. This includes not only health professionals, but also families and people far outside of the clinical space. If their actions combined to deliver an ultimate reduction in cost, it is a fair question to ask why they would not be included in the conversations about how to best to use the savings.

CHARGE TO THE BREAKOUT GROUPS

Following the overview of financing structures and examples by Milstein, participants broke into three groups to discuss what they felt were the key takeaway messages from the workshop presentations to this point. Audience facilitator Chris Parker of the Georgia Health Policy Center charged participants to consider the following:

- What was intriguing, exciting, and/or confusing based on what you have heard?

- How has your thinking or understanding changed or shifted since this morning (if it has)?

- How generalizable or transferrable are these types of efforts from other sectors? Why or why not?

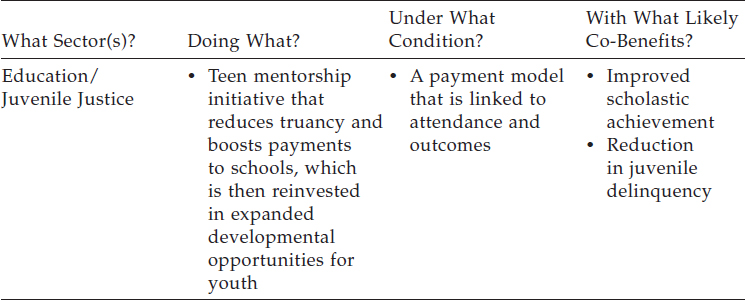

Groups were provided with blank templates to help guide their conversations about ways in which the different financing structures could be used, in principle, to fund population health improvement (see Table 5-2). Participants were also asked to consider their own roles and responsibilities in potentially catalyzing these kinds of efforts.

TABLE 5-2 Sample Completed Template Used for Collecting Small Group Discussion Points

SOURCE: Parker presentation, October 19, 2016.

REPORTING BACK AND DISCUSSION

Key Takeaway Messages from the Workshop

Parker called on each group facilitator to report on some of the key takeaways identified in his or her group discussion. Thomas LaVeist, chair of the Department of Health Policy and Management at The George Washington University, said that his group discussed how bold action was taken in the education and criminal justice sectors with what seemed to be limited evidence—something that would be much harder to do in the health sector. The group was also very interested in the concept of co-benefits. As discussed in the presentations, actions taken in the energy sector can benefit other sectors, including health. There are potential opportunities for the public health sector to support other sectors in their work, whether or not those efforts are explicitly viewed as health interventions. Public health can help other sectors to articulate how health is affected by their priority issues. Supporting other sectors’ objectives, such as improving childhood education, reducing poverty, reducing incarceration rates, or improving housing quality, can lead to health benefits. It was also pointed out, LaVeist said, that one person’s efficiency can be another person’s topline, and that investments in public health are often viewed as costs rather than investments. The group also further discussed the possibility of identifying financing models from other sectors.

Bridget Kelly said that her group felt that several of the examples presented throughout that day might be limited in how well they can be generalized to this roundtable’s conceptualization of population health (i.e., not focused at the individual level) because they were more individu-

ally oriented interventions. The justice case examples were about reinvesting in individual- and family-level care, as opposed to community-level criminal justice issues. Similarly, the Moving to Opportunity example was focused on individual families as opposed to the broader population. Kelly suggested that these examples might be more analogous to risk-factor-based prevention than to the more general field of population health that is the focus of the roundtable.

Kelly’s group also reflected on co-benefits and the place of health in other sectors, and she said that the group members were excited to learn that many of the examples were measuring health outcomes. It was noted, however, that few health institutions or programs offer to hold themselves accountable for their non-health outcomes. For example, health clinics and hospitals are not held accountable for educational outcomes, housing outcomes, or job outcomes. If the health sector is truly committed to co-benefits, it has to be willing to have some sort of mutual contribution to other sectors’ outcomes, as well as to its own.

The group came up with two additional lenses to apply when considering financing structures. One was to consider both operating expenses and capital expenses, acknowledging that public health has little capital expense. The other one was to keep in mind the potential for the structure to work in a multi-sector initiative or collaboration. Some structures might be better suited to single-sector or bilateral efforts versus broader multilateral activities. Kelly added that some group members were encouraged by the success of the justice examples in Georgia in what would seem to be a difficult political environment.

Milstein reported that his group had a comparable discussion about the similarities and differences across these sectors. Participants also expressed interest in the concept of co-benefits and discussed the need to be much more specific in anticipating and calculating those co-benefits.

It was noted that one challenge in population health is dealing with multiple causal factors and deciding where to start. Attempting to cover the entire space of all of the multiple drivers of population health can be paralyzing. It was observed that the cases presented all cut through this predicament, beginning with a menu of options and launching initiatives on select options.

Milstein’s group also considered the time horizon for planning. It was noted that generally speaking, one year’s budget will be only a slight variation on the previous year’s budget. If the population health sector starts investing differently now, will it lead to a different path, allow for much longer time horizon projects, or facilitate partnerships that may not have been possible in the past but could deliver greater value into the future?

Defining Co-Benefits

Participants in all three breakout groups highlighted various aspects of co-benefits as a key takeaway message from the workshop presentations. Because a focus of the workshop was to foster fiscal fluency, Parker highlighted the need to ensure a common understanding of what is meant by the term “co-benefits.” For example, does each party benefit independently, or is there something both parties share that is a benefit to both?

LaVeist suggested that from a population health perspective, everything is a co-benefit because the drivers of population health are all from other sectors and improving public health has positive benefits for all those other sectors. For example, a healthier population results in a healthier workforce, and a healthier workforce can generate more revenue, and so on. LaVeist suggested that “co-benefit” is perhaps a communication or framing device to help garner political support in a policy-making setting.

A participant said that when taking a health-in-all-policies approach to a problem, part of the analysis is to consider who benefits and what portions of the benefits they get. The premise of the approach is that there is not one single entity or sector that will benefit, but rather it is multi-sectoral in both its effort and its benefits. Russo suggested that co-benefits are a mutual win-win and that having a co-benefit can help to propel initiatives forward. Isham observed that the definition is somewhat culturally dependent. For the purpose of promoting population health improvement in the United States, understanding the benefit from a historical or cultural standpoint can help to inform actions and open up possibilities.

Magnan said that a co-benefit can be tangible dollars, and it is important to negotiate how the sectors would share in that benefit. How those dollars would be reinvested to finance other approaches in population health will also need to be discussed.

Financing Solutions

Parker observed that in nearly every example from other sectors that was discussed throughout the day, the health benefit was essentially collateral—that is, it was not necessarily the main intention. The challenge now, as population health considers financing strategies, is to start working with other sectors as partners in making population health happen.

Cross-Sector Agreements for Mutual Regulation Impact Assessments

Kelly reported two pathways to the solutions discussed during her breakout session. The first was inspired by the use of social costs in the energy case examples and by the justice reinvestment model. The group chose the education and health sectors to illustrate the solution,

but Kelly noted that it is not necessarily specific to those two sectors. The approach involves agreeing to mutual regulation impact assessments in the involved sectors. For example, if there is a requirement that schools conduct needs assessments, they would include health in their needs assessments, and, correspondingly, community health needs assessments would include education outcomes in their scope.

The preconditions for this approach would be mutual agreement and reciprocity around how assessments are done, accountability, and how decisions are made regarding what to do with any yields. The hope, Kelly explained, is that this approach would yield co-investment opportunities because of avoided costs or savings or because of new investments. There might be interventions that both sectors would want to invest in because the assessment reveals a clear benefit to both. Other necessary conditions include developing trust between the parties and approaching the assessments in a way that is inclusive of the community that the interventions are intended to benefit. The group noted that different entities might interpret the potential co-benefits differently. For example, hospital systems think of population health relative to their patient populations, while those in the public health sector think of population health relative to the broader population.

Isham asked whether these types of approaches could lead to a reciprocal of health-in-all-policies such that whatever the population health sector does, it must consider energy in all of its policies, criminal justice in all of its policies, and so forth. Kelly responded that limits would need to be set as part of the mutually reciprocal, inclusive negotiations. She observed that at this time, other sectors are being asked to conduct health impact assessments, and health is not offering anything back. A participant suggested that the scope of these agreements would be determined around shared goals and the available evidence regarding potential impacts of the interventions to be funded. For example, if the intent is to invest in social/emotional learning programs in schools, there would be a limit concerning academic outcomes, health outcomes, and perhaps unemployment outcomes as well.

Health–Justice Co-Investment for Broader Reach of Outcomes

The second main approach that Kelly’s group discussed was to broaden the justice reinvestment programs to be slightly less individual-focused. Could there, for example, be joint investment across sectors in programs such as violence prevention, community policing, or behavioral health? A broader population- or community-level approach to the justice initiatives could potentially yield greater safety, which in turn would be expected to lead to a variety of health benefits (e.g., reduced stress).

Tapping Existing Multi-Sector Investments

Milstein said that his group observed that there are many stories of multi-sector investment where multiple parties took actions that they perceived as being in their respective interests but that have not been discussed specifically as co-benefit situations. Several participants suggested it would be worthwhile to reexamine these past examples and gain a better understanding of the different investment philosophies of different sectors and to see where existing relationships in communities could have more population health traction. Milstein also drew the audience’s attention to the Trust for America’s Health report Blueprint for a Healthier America, which was released the morning of the workshop.4 The report contains examples of multi-sector local health improvement collaboratives and identifies and recommends investments that could improve health.

The Role of Business Organizations

Milstein reported that his group discussed the role of businesses and economic development corporations in financing population health. These organizations have choices to make about the types of corporate actors they will be in a particular region. Conditions that would foster their participation include an ethical sense of shared responsibility and a recognition that there are certain costs of doing business in a region that can be figured into corporate budgets, or investments that can yield returns and build a shared economy. There would be a variety of co-benefits to the businesses related to attracting and retaining talent, as well as decreasing costs, for example.

Investment of Sin Taxes

Sin taxes on products such as sugar-sweetened beverages, cigarettes, and alcohol are intended to have the benefit of reducing associated harms such as obesity, cancer, heart disease, and other conditions. A related benefit is potentially reducing health care costs because of a reduction in these health conditions. LaVeist’s group proposed using that tax income to invest in lead-free and clean water, physical education in schools, after-school programs for physical education, and other programs that would have the co-benefits of improving health and improving educational outcomes.

___________________

4 The Trust for America’s Health report, Blueprint for a Healthier America 2016: Policy Priorities for the Next Administration and Congress, is available at http://healthyamericans.org/report/129 (accessed July 25, 2018).

Establish a For-Profit Company with Profits Directed Toward Public Health

Several participants in LaVeist’s group also suggested the notion of establishing a for-profit company with profits directed into equity-based, evidence-based public health interventions. This could be a sustainable model for supporting public health interventions that would improve health outcomes and create jobs.