4

Case Example 2: Clean Energy Financing

Participants continued the discussion of financing in fields outside of population health by considering clean energy financing as another contemporary case example. Michael Bodaken, the president of the National Housing Trust (NHT), discussed the health benefits of affordable housing, the challenges in financing affordable properties, and creative funding streams. Holmes Hummel, a principal with Clean Energy Works and a former senior policy advisor in the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Policy and International Affairs in the Obama administration, examined aspects of financing energy efficiency and how that affects access and participation in the clean energy economy. Joel Rogers, the Sewell–Bascom Professor of Law, Political Science, Public Affairs, and Sociology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the director of the Center on Wisconsin Strategy (COWS), discussed energy efficiency and renewable energy financing. (Highlights are presented in Box 4-1.)

To open the session, moderator Mary Pittman, the president and chief executive officer of the Public Health Institute, highlighted several points of overlap between clean energy and health that she drew from publications by the three panelists. A report from the International Energy Agency, for example, included a benefit–cost analysis, which is common in health care. She observed, however, that health care considers cost–benefit, while the energy report referred to benefit–cost, considering the benefits first in order to reduce bias against energy efficiency. The energy articles showed that data are lacking regarding the positive impacts of energy efficiency in the public sector, similar to the challenge of needing

data to show the benefits of prevention to population health. Another similarity could be seen in short-term variables for tax rates and lifetime benefits for health efficiency, she said. There is a mismatch between the incentives and when the outcomes or benefits accrue. She also observed that there are challenges of silos in both energy and health, referring to an article on indoor and outdoor air quality and the multiple factors that must be addressed simultaneously in order to reap benefits. Finally, she noted a similarity between clean energy and health in terms of the local requirements, different local assets, and local structures that caused those in the energy sector to refine their approach from a generalized state/national approach to an approach that could be implemented at the local level.

FINANCING AFFORDABLE PROPERTIES

NHT is an affordable housing developer, a lender, and a housing policy advocate, Bodaken explained. NHT operates about 4,000 property units along the East Coast and in Chicago and has developed about 25,000 apartments across the United States. Bodaken acknowledged that the health benefits of housing have not historically been the focus of the work of NHT. The mission of NHT was rather to help people get into affordable housing. However, NHT began to hear anecdotally from residents that once their housing had been rehabilitated, they were experiencing unanticipated health benefits such as a reduction in asthma or an increased comfort of living. As an example, he mentioned a property in Southeast Washington, DC, that was taken down to its studs and rebuilt as the first green apartment complex in Washington, DC. Recertified carpets and chemical-free cabinets were among the green features that were installed. The residents reported that they were very happy with the housing and that, for example, a child’s asthma was better and he was not missing school as a result.

More recently NHT decided to focus more on energy efficiency and approached the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) about using weatherization funds broadly in affordable housing. Bodaken said that NHT highlighted the potential health benefits as part of the discussion. He referred participants to workshop background materials describing the strong correlation between energy-efficient affordable housing and health outcomes, and he shared several examples.1 A longitudinal study by the Southwest Minnesota Housing Partnership demonstrated a reduction of about 33 percent in chronic asthma over a period of 5 to 6 years after the energy-efficiency retrofit of its properties, Bodaken said. At the Mission Creek Senior Community in San Francisco, Mercy Housing has instituted health-supported services that have extended some residents’ ability to stay there, delaying their need to move into assisted housing or into nursing homes by 2 or 3 years, and saving the city $30,000 per year. Clearly, there were better health outcomes for the people who were living in affordable housing, and money was saved as well, but Bodaken said that part of the conundrum in these situations is how to allocate resources to pay for these types of programs and initiatives.

___________________

1 See the 2015 International Energy Agency report Capturing the Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency, Chapter 4: Health and Well-Being Impacts of Energy Efficiency, at http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/Multiple_Benefits_of_Energy_Efficiency.pdf (accessed July 25, 2018). See also the workshop attendee packet for NHT fact sheets on affordable housing and health at http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/PublicHealth/PopulationHealthImprovementRT/16-OCT-19/Attendee%20Packet.pdf (accessed July 25, 2018).

Energy Efficiency for All

Bodaken described a model of which he suggested population health might be able to develop an analog. NHT determined that it cost an additional $3,000 per apartment to do an energy efficient retrofit. Although the renovations are good for the tenants, he said, there is no economic reward to the property owner for doing an energy retrofit. In considering what additional financing outside of HUD could be brought to bear to reduce the $3,000 burden, NHT found that private-investor-owned utilities across the United States expend $7.5 billion per year in energy retrofits of schools, hospitals, homes, and other buildings. Tenants, however, reap a scant 0.3 percent of those dollars, even though they contribute to the funding through fees in their utility bills.

To address the fact that residents of affordable housing were not getting the benefit of these funds, NHT launched the Energy Efficiency for All campaign, together with the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Energy Foundation in California. The campaign, now in its third year and in 12 states (California, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia) and the District of Columbia, has secured more than $200 million for energy efficiency in affordable multi-family housing. Bodaken said that utilities were generally unaware of the need until the campaign reached out to them about starting a low-income program that works for rental housing. Most low-income individuals in the United States are renters, he said, and Energy Efficiency for All helped the utilities design and implement more effective utility energy-efficiency programs for owners of affordable housing units. He suggested that it would be very interesting for the utilities to start thinking more about the indirect benefits of energy efficiency, including the benefits to health and to addressing the social determinants of health.

Bodaken acknowledged that the process for Energy Efficiency for All has taken a lot of time and resources. He also emphasized the importance of working with good partners. With regard to health, Bodaken said that housing is where the people live and that health or illness in people’s lives is going to happen in their homes. He suggested that the roundtable think about the home as being the place where it all happens and then think about whom they could work with. Upon reflection, he said, perhaps there should be health care partners added to Energy Efficiency for All. He also emphasized the value of working with leaders in the states, in a state-by-state strategy rather than a national strategy.

INCLUSIVE FINANCING FOR DISTRIBUTED CLEAN ENERGY SOLUTIONS

The clean energy revolution is in progress, Hummel said, but added that it is not happening nearly fast enough.

Industrial Revolution and Climate Change

Hummel highlighted the relationship between modern energy development and human development and noted that metrics for energy development are often used as indicators for human development. The Human Development Report, issued annually by some multilateral development banks, links increased energy consumption with economic development. The association is so robust and persistent over time that some policy makers thought it was irreversible and perhaps non-negotiable, Hummel said. However, the threats to the environment resulting from energy consumption are causing policy makers and the public to rethink the basis for this link. More than 80 percent of the energy in the global economy is fossil fueled. This dependence is creating hazards to health that stress life-support systems around the world. In 2012 the International Energy Agency (IEA) stated that energy-related carbon dioxide emissions needed to be completely eliminated by 2075 in order to limit the global temperature rise to 2°C.2 Furthermore, IEA said that achieving a 2°C stabilization target would require a large-scale additional annual investment in clean energy and energy efficiency in the built environment (power, buildings, industry, transport).

Coincident with the international assessment, a U.S. assessment of the science around climate change found clear connections between population health and the mitigation of climate change impacts.3 Hummel summarized the key findings of the report: there are wide-ranging health impacts of climate change, certain populations are especially vulnerable, preparedness and prevention provide protection from the impacts of climate change, and taking action on climate and other types of co-related pollutants can improve health and provide other social benefits.

In the United States, the costs associated with extreme weather disasters attributed to a changing climate are not distributed equally, Hummel said. People in the southern states are on the front line of these disasters and are incurring huge losses, despite the emergency aid that is sent. These costs need to be factored into choices made about future invest-

___________________

2 See http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/ETP2012_free.pdf (accessed July 25, 2018).

3 The National Climate Assessment is available at http://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/sectors/human-health (accessed July 25, 2018).

ment, Hummel said. The U.S. federal government has also assessed the social cost of carbon, and it factors these values into the cost–benefit analysis of every regulation that would affect carbon dioxide emissions.4 Previously, Hummel said, a major gap in public policy analysis had been the assumption that carbon dioxide pollution had zero social costs. It is estimated that the social cost over the next 10 to 15 years will be between $40 and $50 per metric ton of carbon dioxide. This type of calculation can have an important and profound effect on the regulatory impact analysis of energy policies.

Recovering Social Costs and Harnessing Public Spending

The social cost of carbon is a “shadow price,” and it does not affect the economy until someone actually has to pay it. Hummel discussed what it would mean to recover some portion of that social cost for public benefit.

Carbon pricing policy in the northeastern states is more advanced than in other parts of the country, Hummel said. Over the past decade, the northeast has generated more than $1.5 billion in public receipts that have then been available for public spending. This is the result of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative cap-and-trade program. Hummel briefly explained that a cap-and-trade program sets a price on carbon that is designed to send a signal to private-sector actors that pollution is not free. In that system companies must pay for the “permission to pollute” by buying allowances that are available to them through an auction. The auction fetches on the order of $3 to $4 per ton of carbon dioxide (ranging from about $1 to $5), which is only 10 percent of the social cost of carbon that the federal government has assessed. This means that even after discounting the social cost of carbon by 90 percent, the northeast produces billion-dollar-scale benefits which are then associated with public spending programs that can be informed by public health experts. Each state determines how the money will be spent, and energy efficiency has been the top investment priority in each of these states except for Maryland (the priority investment in Maryland was in direct financial assistance with paying utility bills).

Contours of the Clean Energy Divide

Public spending is not enough to overcome the barriers encountered in the clean energy revolution, Hummel said. The scale of the demand

___________________

4 For more information on the social cost of carbon, see https://web.archive.org/web/20170121004634/ https://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/Downloads/EPAactivities/social-cost-carbon.pdf (accessed July 25, 2018).

is too big for public spending alone, and the vast majority of the money will need to be sourced from the private sector. Even with private-sector capital, there will be barriers to progress. Multiple factors affect the pace at which mitigation policies are adopted across the United States, including a sensitivity to price impacts. For example, in vulnerable communities (areas in which electricity costs constitute a greater share of household income), there is less enthusiasm for clean energy policies that might increase the cost of electricity. Persistent, underlying conditions of inequality (i.e., poverty) affect the distribution of these impacts. Hummel said that the NAACP has highlighted the dimensions of equity that affect the clean energy future of the United States and has called for directed investment policies to address long-standing environmental injustice and to increase opportunity.5 Hummel observed, however, that even where those investment policies are in place, barriers to investment persist, producing a clean energy divide.

Ninety percent of the persistent-poverty counties in the United States are served by electric cooperatives. These are utilities where the customers have an ownership stake in the utility and a shareholder vote. Co-ops cover more than three-quarters of the United States, serve more than 40 million people, and together buy $40 billion of electricity. Hummel said that the Roanoke Electric Cooperative in Down East, North Carolina, is the only utility in the United States that is led by people of color and serves majority people of color communities. Common qualifying criteria for loans and leases across the United States are home ownership, credit score, and sufficient income. Based on these criteria, Hummel said, nearly all members of the Roanoke Electric Cooperative were disqualified from receiving low-interest loans for investments in energy efficiency. Hummel reiterated the point by Bodaken that more than half of people below median income are renters and, as such, face barriers to entering the clean energy economy, and he added that inclusive financing solutions are needed.

Inclusive Financing for Distributed Energy Solutions

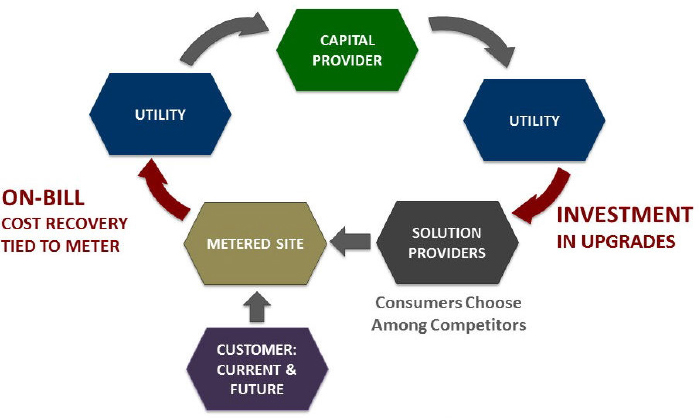

Pay As You Save® (PAYS®)6 is a utility financing solution that offers all customers the option to access cost-effective energy upgrades using a proven investment and cost-recovery model that benefits both the customer and the utility, Hummel explained (see Figure 4-1). The utility

___________________

5 See http://www.naacp.org/climate-justice-resources/just.energy (accessed July 25, 2018).

6 Pay As You Save® and PAYS® are trademarks of the Energy Efficiency Institute, Inc., of Vermont, which works with both municipal and investor-owned utilities.

SOURCE: Hummel presentation, October 19, 2016.

draws low-cost capital from its usual sources and invests in cost-effective distributed energy upgrades (e.g., better building efficiency, rooftop solar arrays). The utility pays the installer; the customers pay nothing upfront for the upgrades they choose. Costs for the solutions installed are tied to the meters they serve. Costs are recovered on the customer bill with a fixed monthly charge that is less than the estimated savings generated by the upgrade. In this way the customer is then participating in the cost recovery without being personally assigned a debt obligation (and does not suffer the financial sector scrutiny required for upfront loans or leases to join the clean energy economy).

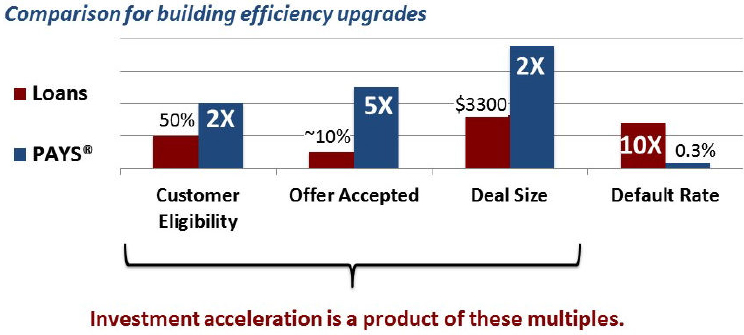

The PAYS® solution is an inclusive approach to a clean energy future. There is no consumer loan, lien, or debt; it reaches renters and low-income market segments that are chronically locked out; it leads to higher uptake rates; and it produces deeper energy and carbon savings, Hummel said. Compared to loan-based or debt-based instruments, inclusive financing allows for a larger addressable market, greater acceptance of the financing offer, bigger projects that produce deeper savings, and fewer defaults (see Figure 4-2). Hummel said that the Roanoke Electric Cooperative and several others have been able to demonstrate the success of PAYS® in persistent-poverty regions of the United States.

The results have been impressive, Hummel said, resulting in an immediate surge in investment. Hummel shared results from the Ouachita Electric Cooperative in Arkansas as an example. Comparing the first 3 months

SOURCE: Hummel presentation, October 19, 2016.

of its inclusive financing program to the best 3 months of its debt-based program showed that within less than 4 months it was able to double the number of customers; achieve 100 percent opt-in by multi-family rental units and greater than 80 percent opt-in by single family units; and double the scale of capital improvements. As a result, it quadrupled the investment deployment in a community that experiences persistent poverty.

THE FUTURE OF CLEAN ENERGY

Rogers shared his perspective on some of the financing challenges of advancing clean energy approaches. He suggested that by 2050—assuming a world population of nearly 10 billion—energy consumption will likely be more than double what it is today. While the vast majority of energy currently produced is fossil fuel–based, the market share of renewable energy sources (e.g., solar, geothermal) is steadily increasing. Rogers acknowledged the optimism about efforts to address climate change concerns, such as the Paris Agreement and the recent agreement on reducing the use of refrigerants. He noted, however, that even if all of the Paris Agreement commitments are met and pledges fulfilled, the world will still fall far short of the goal to limit global warming to 2°C above what it was in preindustrial times.

Energy Has Value

Energy has a lot of value, Rogers said, and anything with value can be financed. Spending on energy is huge, accounting for about 9 percent

of the U.S. gross domestic product, or just short of $2 trillion. The United States consumes about 100 quads of energy per year,7 and more than half (about 55 percent) of the energy consumed is wasted in various ways. Rogers suggested that the United States wastes more energy in its electric power generation sector alone than Japan uses in an entire year. Where there is waste, he continued, money can be made by reducing that waste.

Individuals spend money directly out of pocket for energy and increasing energy efficiency can result in direct savings to individuals. Energy, housing, transportation, water, and other systems are highly connected in terms of cost. Because these systems supply basic needs, inefficiencies within them disproportionately affect people with limited resources. The poor spend a greater percentage of their income on these needs and tend to live in areas where these basic needs are less well provided. Rogers mentioned several initiatives to address these inequities through financing, such as PAYS® (discussed by Hummel, above), and the Property Assessed Clean Energy program for homeowners, which pays for energy efficiency upgrades and recoups the costs through a property tax assessment. Rogers also noted that renewable energy sources are becoming more competitive. The price of solar panels, for example, has dropped about 80 percent, and efficiency has increased significantly over the past 5 or 6 years.

Fixed Costs

One of the main challenges in changing the energy landscape is the presence of fixed costs and fixed investments, which are deeply connected to social and political capital. Change takes time, Rogers observed, noting that there are still homes in the United States that are heated by coal- or wood-burning stoves, despite the broad transition to oil, natural gas, electricity, and other potentially cleaner forms of energy consumption. Investments in many old-style coal-burning power plants are fully amortized, as are investments that were made in other infrastructure for the “dirty energy system.” People see opportunity in resisting change, so they can continue to get money out of older equipment. The Clean Power Plan for existing power plants is aimed at reducing carbon emissions through such measures as converting coal plants to natural gas. Rogers suggested the need for discussions about the limits of that plan, in terms of actually changing the fundamentals of the U.S. utility model.

Globally, the world must adapt to a “carbon budget” that is only about 550 gigatons more than today’s usage if it is to avoid the catastrophic temperature increase to 2°C above preindustrial levels, Rogers

___________________

7 A quad is a unit of energy that is equivalent to 1015 (one quadrillion) British thermal units.

said. If the world went on a very strict carbon budget and ramped up all of the renewable energy efforts, particularly solar, the goal would be achievable within 30 years, he said. The problem is not the investment in clean energy, but the fact that there are 2,795 embedded carbon gigatons in booked reserves of oil and natural gas and other carbon sources. This is more than five times the amount that humanity can spend, he pointed out. The booked value of these reserves is in excess of $30 trillion. In essence, he said, saving humanity would take $30 trillion away from the holders of these reserves, which is a significant political problem.

State and Local Politics

Housing, transportation, and energy policies all affect the built environment, and all have considerable effects on public health. These policies are, in general, the outcome of state and local politics, Rogers said. Energy policy is almost entirely set at the state level. Energy policy is also intensely dominated by narrow business interests. Recently, he said, it has also been an area where competitive federalism has become increasingly nationalized, in a particularly problematic way.

Unlike justice reinvestment, in the energy arena the fossil fuel companies and utilities have significant power at the local level to push back against clean energy development. The business model is to sell more energy, not less. Rogers noted the increasing difficulty of working in partisan state government environments. He lamented the focus on privatizing public goods, even when such privatization presents challenges for a state’s economy or may not even be in tune with constituent expectations. He raised concerns that this is a dangerous step back from health-based, resiliently financed, community-based solutions.

DISCUSSION

During the discussion following the panel presentations, the speakers expanded on financing approaches for energy efficient upgrades, especially for renters and low-income residents. Participants also discussed the value of place-based strategies that produce co-benefits in fostering equity and considered the impact on workers and communities when an industry changes or leaves an area, resulting in job losses.

Financing Energy Efficiency Upgrades

Russo observed that in the examples that had been discussed, the utilities appeared to not even think about renters at first. She asked for further discussion about the funding for retrofitting buildings and other

such projects in rental units. She also wondered whether an energy utility’s only reason for pursuing energy efficiency is because it is regulated and required to do so.

Bodaken clarified that nearly everyone pays a utility bill, and most utility bills in the United States include a small fee that goes toward funding energy-efficiency programs (called ratepayer funds). Those fees stay with the utility that collects them, he said. The programs are state- or utility-based and vary from facility to facility (i.e., this is not a federal requirement). There are still some utilities that do not have energy-efficiency programs. As discussed, the Energy Efficiency for All campaign is not generating new resources, but rather is reallocating existing resources to those who need them most. In this case, most people who are poor rent their homes, and extremely low-income renters are significantly burdened by high utility bills that consume large portions of their income. Reallocating existing energy-efficiency resources toward rental housing accounted for a relatively small amount of money, but it is an approach that can begin to show an impact on an annual basis. The strategy, Bodaken suggested, is that once a utility company sets up a program, a nonprofit developer, such as NHT, can leverage that program along with its other resources to rehabilitate rental living spaces. Sometimes utilities do this type of initiative on their own, but more often it is other groups that lead the effort.

Rogers pointed out that energy-efficiency programs are a relatively small part of a utility company’s overall budget. He noted that there are private-sector energy service companies that serve both public and private clients and that make their money through energy efficiency. They establish energy performance contracts in which the energy efficiency upgrades are financed and then repaid through the accrued savings (similar to the PAYS® example described by Hummel).

Hummel added that the inclusive financing programs he described do not use utility ratepayer funds as they do not provide the level of funding needed for the scale of the problem. They look to the same sources of public and private financing that are used to build substations, extend transmission and distribution lines, or pay for smart grid upgrades. Hummel said that there are convergent interests between utilities and their customers in distributed energy solutions. Financial analysis of utilities involved in inclusive financing has shown large-scale benefits to the utilities in reducing their costs for peak demand. Hummel suggested that this could be likened to addressing the cost of emergency department care in the health sector.

Place-Based Strategies That Provide Co-Benefits and Foster Equity

Pittman observed that all of the speakers raised the issue of equity in their presentations and highlighted the mismatch between those in power and where the dollars are most needed. For example, she reiterated Rogers’s point that the booked value of current carbon reserves is $30 trillion, but action at the state and local levels is directed toward the people who are most affected (e.g., by unemployment due to change in energy generation). Rogers responded that place-based strategy development can help address this gap by adding value, reducing waste, and capturing and sharing the benefits of doing those two things. Place-based approaches can be used in a variety of policy areas, including energy efficiency, transportation, and housing, and they can be pursued in alliance with the business community. It is possible for businesses to be profitable by “taking the high road,” Rogers said, noting that many firms are willing to pay workers decent wages and provide pensions and other benefits in order to produce a quality product. The challenge is that their “low road” competitors (firms that are not willing to treat employees as valuable assets) are constantly threatening their profit margins. Furthermore, Rogers said, the “high road” companies do not have effective champions in the political arena in most states. He observed that there are many smaller communities that have lost significant human capital (which can be seen in, for example, the increasingly empty high schools that are being shuttered). The members of these communities have, in a sense, lost the narrative of their lives, and they often turn against each other and against those who are even more vulnerable. There is a healing process that needs to occur, Rogers said. The people in these communities have the same interest in having clean water, good local schools, or broadband Internet access as residents of cosmopolitan areas do, he said, and he suggested the need for urban–rural progressive political coalitions.

Bodaken agreed with the place-based approach and suggested that most Americans do not really want to relocate to some distant place and give up their identities in the process. He predicted that electric utilities will need to change their entire way of doing business in the relatively near future. Some states, including California and New York, are beginning to change how they operate with regard to power generation, he said. In Maryland, the government sought to build a new, billion-dollar power plant on the Eastern Shore and explained to local citizens that they would have to pay more for their electricity once that power plant was built. After the residents responded that they did not want that power plant in their community, the company developed a strong energy efficiency program that actually reduced resident’s costs and provided jobs. Bodaken acknowledged that such approaches cannot address the $30 trillion of embedded investment in carbon energy sources, but it is a start,

and there are co-benefits to consider as well, such as the health of the community. From a financing perspective, insurance companies would likely have a significant interest in reducing their members’ exposure to contaminants from traditional power-generation approaches.

Rogers concurred with the importance of co-benefits in these approaches, and he reminded participants to look for such co-benefits as they might not be obvious. He cited Bodaken’s example of the apartment complex in the District of Columbia that was stripped down and rebuilt as a green building and how residents were happy with their rent and the space, but they were most pleased about the unexpected co-benefit that their children were healthier and were not missing school because of asthma attacks.

Hummel pointed out that clean energy clearly has the advantage over traditional energy sources when all the social costs of pollution are counted. In the current market conditions, many of these costs are externalized by the companies and then internalized by society. As discussed, those costs are not spread equally. Hummel advocated for 100 percent clean energy, which means clean energy for everyone. Many current financing solutions in use are disqualifying large segments of the population. Hummel suggested that inclusive financing options can produce inclusive results and can accelerate the rapid scaling-up of the necessary capital deployment. Inclusive financing can also help to build a political constituency for the policies that will change the market conditions framing private-sector investment decisions. There is good work to be done at the intersection of energy, environment, and finance, Hummel said, and public health benefits can accrue when people who are burdened by energy costs are relieved of the sacrifices they make to keep the lights on.

Bodaken described a longitudinal study that is assessing the public health benefits of upgrading the energy efficiency of 8,500 apartments in Chicago, New York, and San Francisco. The findings will available in 2020. The study is being done by the JPB Foundation, in partnership with the National Center for Healthy Housing; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; the University of California, San Francisco; and the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The Human Impact of an Evolving Commercial Sector

Flores said that corporate maneuvers, such as changing where energy is sourced, are not necessarily transparent to the public. Enormous amounts of money are exchanged, and those involved are far outside the realm of middle-class and lower-class America. All that the consumers understand is that they are not necessarily any better off. Flores stressed that policy discussions should include representation from labor organi-

zations and from the communities that will be affected by these significant changes. For example, shifts in energy policy will affect people employed in the coal or oil industries, and the towns where these industries are can be decimated when jobs are eliminated. Flores stressed the need to have solutions for the people who will no longer be employed or who will lose a major portion of their income as a result of these shifts in energy policy (e.g., retraining, re-employment).

Rogers said that his center at the University of Wisconsin has released three reports on the issues facing people displaced by changes in the industry and on the likelihood of reemployment in other sectors (Walsh et al., 2008; White and Gordon, 2010; White et al., 2012). He suggested that there will be numerous employment opportunities in the United States to either create or maintain the clean energy infrastructure that will be needed going forward. One issue will be whether displaced employees will be willing to move to where the new jobs are.

Bodaken agreed with the concerns raised by Flores. The answer will probably be a combination of re-employment (i.e., of displaced energy sector workers) and defining the new jobs and determining what the required skills and training are. Bodaken noted that NHT previously purchased solar panels that were manufactured in China, but this year and last year they were able to buy solar panels from a company in Buffalo, New York. He agreed that there are jobs being created in the United States, but he added that there will also be potentially millions of jobs lost.

Hummel likened the impending economic dislocation to what took place at the end of the whaling industry or during the decline of the tobacco industry following public health anti-smoking campaigns. For most of the 20th century the eastern Kentucky region has been the source of most of the coal burned in the most densely populated parts of the United States, Hummel said. It has also been the site of massive fossil fuel extraction. Inclusive financing programs for clean energy in the coal fields of Kentucky have demonstrated that this approach can be successful in a region with persistent poverty, Hummel said.

Hummel referred participants to a 1990s tobacco settlement in which public health experts were instrumental in framing the costs and benefits to society of managing the dislocation of workers. The point from that example is that workers who lose their employment in the energy sector should be given the opportunity to access education and support for entrepreneurship to pursue jobs in any part of the economy and should not simply be tracked from one part of the energy sector to another.

The goal should not be simply neutrality or doing no harm, Flores said, but recompense. For example, perhaps new factories for solar panels could be built in the communities that are losing other employment. Financing should be embedded in places where there has been disinvest-

ment, he said. He offered the revitalization of Detroit as a case example. Reinvesting in these places and populations across America can help to build back equity.

Rogers agreed with the need for strategic reinvestment in the infrastructure and industries necessary to make the clean energy transition in the United States equitable. He added, however, that this approach will not solve all of the problems in these areas of poverty and that there are other issues beyond the energy sector that are affecting these populations and that need more attention.

A participant pointed out that these arguments are finding their way into the political conversation and cited an example of a person running for office calling for plans to help those displaced in the shutdown of a refinery in the area.