3

ARPA-E’s Internal Operations: Culture, People, and Processes

In accordance with its statement of task (Box 1-1 in Chapter 1), the committee undertook an operational assessment to “appraise the appropriateness and effectiveness of the agency’s structure to position it to achieve its mission and goals.” This chapter describes and assesses ARPA-E’s internal operations, addressing the following specific charges in the statement of task:

- Evaluate ARPA-E’s methods and procedures to develop and evaluate its portfolio of activities;

- Examine appropriateness and effectiveness of ARPA-E programs to provide awardees with non-technical assistance such as practical financial, business, and marketing skills;

- Assess ARPA-E’s recruiting and hiring procedures to attract and retain qualified key personnel;

- Examine the process, deliverables, and metrics used to assess the short and long term success of ARPA-E programs;

- Assess ARPA-E’s coordination with other Federal agencies and alignment with long-term DOE objectives;

- Provide guidance for strengthening the agency’s structure, operations, and procedures;

- Evaluate, to the extent possible and appropriate, ARPA-E’s success at implementing successful practices and ideas utilized by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), including innovative contracting practices; and

- Reflect, as appropriate, on the role of ARPA-E, DOE, and others in facilitating the culture necessary for ARPA-E to achieve its mission.

DEFINING ORGANIZATIONAL FEATURES OF ARPA-E

Through the course of its deliberations and analyses of the evidence gathered for this assessment, the committee found that ARPA-E benefits from three defining organizational features:

- The director exercises technical and leadership skills that enable a culture of empowerment to be sustained.

- ARPA-E’s program directors are empowered with the authority, responsibility, and ability to make program- and project-related decisions.

- Active project management is important to ARPA-E.

Collectively, these three features have the potential to contribute to ARPA-E’s ability to achieve its intended mission and goals. The absence of these features would not guarantee failure, and their presence does not ensure success. However, these features are important to creating conditions that can enable success. ARPA-E’s culture of openness and empowerment encourages risk taking. ARPA-E’s program directors have wide autonomy to develop new focused technology programs and manage projects within those programs. The agency selects projects to fund through a multifaceted process that entails evaluating each project’s potential, if successful, to help achieve the agency’s goals instead of adhering strictly to ranking of external peer reviewer scores.

This chapter presents the evidence supporting the importance of these organizational features, together with the committee’s findings and recommendations on ARPA-E’s internal operations.

METHODS

The committee developed a framework for evaluation based upon the individual charges mandated in the statement of task. As described in detail in Appendix C, the committee used both qualitative and quantitative methods to address the implicit research and evaluative questions associated with each of these charges. Qualitative methods included reviewing archival ARPA-E planning documents (e.g., strategic planning documents and annual reports), as well as solicitations, application and selection processes, and per-project milestones; consulting with present and former employees of ARPA-E and other U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) offices and programs, performers,1 and other experts; and attending agency program meetings and the annual Energy

___________________

1 “Performers” is the term used to denote ARPA-E awardees.

Innovation Summit to identify and observe key stakeholder interactions. Quantitative methods included examination of descriptive statistics and regression analysis of data related to the program directors’ roles, responsibilities, and activities.

From this rich collection of data, a picture emerged of the three defining organizational features listed above. The remainder of this chapter explores these features in detail. The chapter ends with a summary of the committee’s findings and its recommendations with respect to ARPA-E’s internal operations.

ARPA-E’S CULTURE, PEOPLE, AND PROCESSES: A QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

ARPA-E exhibits a number of features that suggest the organization’s policies and practices, internal structure, and culture are interlinked and interdependent in a way that are essential for strategic management of innovation (Kfir, 2000). Organizational culture has been found to have a particularly important role in supporting technology innovation since it unites the aims of individuals in the organization to achieve excellence by encouraging repeatability of behaviors, actions, and attitudes for both individuals and groups (Berry et al., 2006; Hurley and Hult, 1998; Koźmiński and Obłój, 1989; Lyons et al., 2007; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, 2014; Tellis et al., 2009). Culture is also important for enabling public agencies to recruit and retain talented personnel to execute on agency mission and maintain institutional memory (Goodsell, 2011). Much as at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), ARPA-E seeks to maintain a culture that encourages key staff to commit to advancing its mission while generating the admiration and respect of those outside of the agency—essentially the “mission mystique” (Goodsell, 2011).

Culture is interdependent with people and processes. The latter are where a cultural orientation toward innovation become operationalized to help an organization achieve its objectives (Bina, 2012; Gonzalez-Padron et al., 2008; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, 2015, p. 397). In the innovation context, this refers to an organization’s willingness to chart new territory and orient toward future and external events while thinking beyond what technology the market currently demands to envision what will be useful and in demand—or even transformational—if developed (Christensen and Bower, 1996; Narver and Slater, 1990; Tellis et al., 2009; Yadav et al., 2007).

When it comes to people, empowering individuals allows innovation-oriented organizations to recruit and retain top talent. Such empowerment is a critical element of seeking new directions and fostering innovation rather than being incentivized only to seek short-term commercial rewards (Aghion et al., 2010; Kfir, 2000; Nijstad et al., 2012; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, 2015).

The findings reported here were drawn from a quantitative analysis focused on ARPA-E’s discretion to select projects for funding through a process

that relies on program director discernment and discretion rather than strict adherence to a particular bureaucratic process; to fund projects that may appear riskier than others but are deemed to hold greater potential for impact if successful; and to engage actively in ongoing projects by altering project milestones, budgets, and timelines when necessary. This quantitative analysis was supplemented by a qualitative analysis drawn from discussions with the founding ARPA-E director; current and former program directors; leaders of other DOE offices and programs, including those at the national laboratories; presentations at the study committee’s meetings by ARPA-E leadership, DARPA leadership, and other outside experts;2 and case studies prepared by the committee (Appendix D). Appendix C briefly describes the methods used in developing this analysis. Full details are found in the consultants’ reports (Appendix G).

ARPA-E’s Culture of Innovation and Risk Taking

Research points to four critical organizational elements related to culture that promote innovation: (1) exceptional tolerance for failure, (2) the ability to deal with uncertainty and risk, (3) strong communication channels, and (4) nurturing leadership (Amabile et al., 1996; Holmstom, 1989; Hurley and Hult, 1998; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Kanter, 1983; Lyons et al., 2007; Nelson, 1962; Rosenberg, 1996; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, 2015; Utterback, 1974). A number of ARPA-E’s activities and procedures indicate the agency features a culture focused on talent, openness, and empowerment that encourages risk taking, and hence a high tolerance for flexibility to learn what does not work on a path producing innovative outcomes. This tolerance of failure of is an important characteristic of organizations or researchers seeking to produce innovative outcomes since learning what does not work at the level desired can be quite valuable and often provides guidance for ultimately developing a successful technology. A friend of Thomas Edison, for example, once learned that the inventor and his team had conducted more than 9,000 experiments in an attempt to develop nickel-iron batteries to no avail, and opined as to what a shame it was to have wasted the effort. Edison famously retorted that the effort was not wasted but had produced many results and revealed “several thousand things that won’t work” (Dyer and Martin, 1910, p. 616). This means, however, that outcome metrics for innovation are inherently noisy, and decision making around innovation must be less sensitive to performance (Holstrom, 1989). Hence much focus on metrics has gone to more easily observable ones such as organizational attributes, specific actions that are known to support and encourage innovation, and intermediate outputs.

___________________

2 Agendas from committee meetings providing the names and affiliations of presenters are included in Appendix F.

A critically important difference between ARPA-E and other DOE offices is its statutory mandate to identify and promote ideas with the promise of being revolutionary, and to support ones that industry is unlikely to support alone. In other words, ARPA-E was created to tolerate risk and foster activities that would lead to transformative technology innovations and to do so by being structured and operating in ways that are innovative for a DOE program. Two styles of managing research for innovation have been described in the literature. One is exploitation, where the research is aimed at producing incremental improvements along a known technology development curve. Exploration, on the other hand, seeks to discover entirely new technology development curves. Exploitation often entails the use of known research tools and activities, while exploration involves potentially wasted effort, inferior actions, and many early failures. Some researchers suggest that nurturing these two different types of innovation requires different management practices. On the one hand, exploitation can be incentivized effectively with standard short-term, pay-for-performance contracts and strict termination rules for failure. On the other hand, motivating exploration requires tolerance for failure and long time horizons (Manso, 2011).

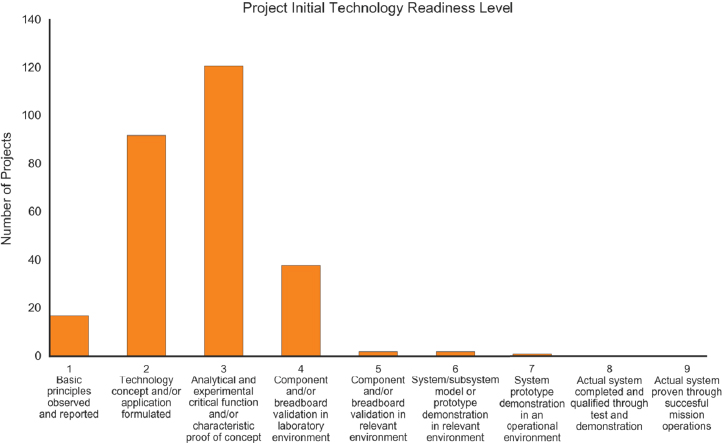

At first glance, ARPA-E may appear to fall squarely within the exploration parameters that Manso describes. On closer inspection, though, some ARPA-E activities could be characterized as attempting to exploit as yet uncaptured value along known technology development curves. As seen in Figure 3-9 later in this chapter, ARPA-E projects, by design from the agency’s mandate, can be seen as sitting mostly in “Pasteur’s quadrant,” at the intersection of basic and applied research (Stokes, 1997). Such organizations are sometimes called “ambidextrous” since, in an innovation context, they are trying both to explore and exploit (Tushman et al., 2010). ARPA-E is organized to include “an interrelated set of competencies, cultures, incentives and senior team roles,” suggesting that it can simultaneously and cost-effectively promote exploration and exploitation, and thus should be better positioned to support innovation compared with organizations with singular organizational designs (Tushman et al., 2010). ARPA-E’s differentiation among its programs and projects suggests that the agency may be positioned to exploit this ambidextrous advantage, although evidence of the agency’s long-term performance will be seen only over time.

Given ARPA-E’s mandate to seek out and support risky but potentially valuable technology, the agency must be able to deal with risk and uncertainty. One recognized way to mitigate the risk of uncertainty is to focus research on learning rather than achievement of results (Nelson, 1962). Rosenberg (1996) argues that innovation is an inherently uncertain task, making it impossible to know the probability distribution of outcomes. Thus, for ARPA-E to be well positioned to support innovation, it must maintain an appetite for risk and uncertainty (Amabile et al., 1996; Hurley and Hult, 1998; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Kanter, 1983). This observation is intuitive since by “definition, innovation is a novelty-producing process, consisting of a string of non-routine

decisions made under uncertainty” (Lyons et al., 2007, p. 182). The organization must also have its own capacity for change and internal innovation. An open culture receptive to new ideas, willing to experiment with procedures and programs to improve them, allows a public agency to be a dynamic partner in innovation (Goodsell, 2011).

The evidence presented later supports the notion that ARPA-E’s director and program directors seek to develop focused programs based on new ideas and risk, supporting those ideas they believe have enough potential to warrant investment. Both qualitative and quantitative evidence points to cultural norms and values at the agency that attract such risk-oriented individuals and encourage them to seek out truly new ideas and pursue those with the potential to be transformative. Such a cultural norm of empowering staff is a critical element of fostering innovation (Kfir, 2000; Nijstad et al., 2012; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, 2015). This means an ability to avoid the incrementalism often found in government programs that fund research.3 Ideas funded by ARPA-E need not fit neatly into one specific category, but this does not mean the ideas are passed from office to office.4

A key challenge for any organization is to promote innovation without producing uniformity of ideas (Lyons et al., 2007). One such norm that can help support the search for new ideas is to encourage constructive intellectual debate on ideas (Lyons et al., 2007). Nearly all of the individuals consulted during this study mentioned this norm and its importance for ARPA-E, pointing to the agency’s early adoption (and adaptation) of the well-known core norm of “constructive confrontation” made famous by Intel CEO Andy Grove (Staley, 2016). At ARPA-E, constructive confrontation entails two key features. First, individuals can debate the technical merits of ideas without fear of reprisal and with confidence that any criticism offered will be taken as constructive, with the intent of strengthening the ideas, rather than as a personal attack. Second, the committee repeatedly heard that the program directors and other staff have genuine camaraderie with each other. They have a professional rapport and trust that they are working together for the common goal of achieving the agency’s mission and goals. This gives ARPA-E staff—and especially program directors—the confidence to take risks, pursue ideas with the potential to create something new, and freely communicate with anyone in the agency (Berry et al., 2006).

Individuals consulted for this study reported that ARPA-E demonstrates strong communication channels across the agency at both the structural and cultural levels. Program directors all demand rigorous critiques of their pitches for new focused technology projects. Several former program directors expressed the sentiment that the worst thing that can happen when an idea is first

___________________

3 Interview with Le Minh.

4 Interview with Ravi Prasher.

pitched is for no one to challenge it. Program directors also expect that the agency director will engage with them, providing critique and feedback regarding programs and projects, and do so constructively and in a way that program directors do not fear personal attack or reprisal. These strong communication channels constitute an important tool for dealing with uncertainty in research and development (R&D), being both a source of idea production and a means for problem solving (Utterback, 1974). While planned coordination is insufficient for the transfer of knowledge within an organization, open lines of communication are necessary in settings where outcomes are uncertain. An organization’s structure can either augment or impede internal communication as well (Utterback, 1974). The importance of this culture is seen at ARPA-E’s “Program Director Week,” a twice-a-month event when all program directors are required to be in the office to build camaraderie, embrace constructive confrontation, and share lessons learned in developing and managing programs.

ARPA-E’s mandated focus on innovation means the agency needs to be orientated to the future. Maintaining a future orientation means evolving and adapting processes intended to identify potentially groundbreaking ideas and technologies. ARPA-E has described its processes as the search for “white space.” Searching for white space for ARPA-E entails pursuing two distinct but related areas of research with the objective of producing energy technology innovations: the first is the pursuit of technological ideas or approaches that are truly novel or greatly underexplored; the second is a deliberate attempt to fill gaps left in other research or funding programs. In addition to this search, future orientation means keeping an influx of talented program directors empowered to seek white space, construct new programs, and actively guide their projects. Building and maintaining a future-oriented culture in turn requires the creation of new learning curves for the pursuit of white spaces, as well as expertise, enthusiasm, and initiative across the agency.

People Who Support ARPA-E’s Culture of Innovation and Risk Taking

Intellectually, it is difficult to separate the impact and role of people from culture and processes, a difficulty reflected by the evidence gathered for this study. People build and maintain an organization’s culture, and agency culture was an oft-cited reason for wanting to work at ARPA-E. Nonetheless, it is useful to consider here the roles played by key agency personnel. This section presents qualitative data and quantitative data with descriptive and analytical statistics for key attributes of program directors to enable a better understanding of their characteristics and active management practices. To conduct these analyses, the committee worked with external consultants who examined anonymized data detailing the specific performance of individual projects against award

milestones. Those data were provided by ARPA-E and anonymized and aggregated to protect sensitive information.5

The body of research on managing R&D for innovation strongly suggests that ARPA-E can help ensure a culture supportive of innovation and risk taking by attracting and hiring (1) a visionary and technically expert director who creates an environment that demands new ideas, change, and risk and hence tolerance for failure; and (2) empowered program directors who want to work in such an environment. The committee evaluated the data gathered by its consultants. While the dataset is of high quality, it must be understood in context. As mentioned several times in this report, ARPA-E is a relatively young agency, and so the available time series is short and catalogs only its initial years, in this case the first 6 years of agency operation. While such a short time series does not allow for drawing conclusions as robust as policy makers may want, the data still clearly suggest that ARPA-E has done well in this regard.

Leadership and Vision of the ARPA-E Director: Qualitative Analysis

As noted above, the committee identified the director’s key role in ARPA-E as a defining organizational feature of the agency. The director bears significant responsibility for ensuring that program directors are empowered and for fostering and sustaining a culture that promotes innovation. The director also holds high responsibility for preserving and updating the values of the agency’s mission—putting them into practice (Terry, 2003). The importance of this responsibility was reinforced through the committee’s discussions with former ARPA-E directors, program directors, and others who interacted with the program while at DOE.

ARPA-E’s director is expected to establish and nurture an organizational culture that increase the agency’s capacity to promote innovation. A principal challenge is managing “the inherent paradox between a strong culture and innovation” (Lyons et al., 2007, p. 182). Key ways to do this include (1) serving as a role model by focusing on the agency’s interests rather than personal gain; (2) articulating an inspiring, energizing vision; (3) fostering intellectual stimulation by encouraging challenges to the status quo; (4) providing individualized consideration and support for team members; and (5) ensuring that the organization designs and implements structures, systems, and processes that reflect and establish an innovation-oriented culture (Bass, 1985; Hurley and Hult, 1998; Lyons et al., 2007; Nijstad et al., 2012, p. 312; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, 2015). These structures, systems, and processes are important in

___________________

5 The working paper developed by Goldstein and Kearney (2016) includes a more detailed description of the data collected, the methods used, and the authors’ analysis and conclusions. The authors can be reached via email at anna_goldstein@hks.harvard.edu or mkearney@mit.edu.

attracting talented personnel who can achieve an organization’s mission and goals (Szczepańska-Woszczyna, 2015).

Discussions with personnel from ARPA-E and DOE suggest that ARPA-E personnel already have an intuitive grasp of the importance of leadership, especially transformational leadership, in fostering the agency’s capacity to carry out its mission. The consulted individuals emphasized the importance of leadership to performance, to attracting talent, and to enabling the agency to pursue ideas with the potential to be radically innovative. They also emphasized that it is critical for leaders to create a climate where specific aspects of a culture of innovation can flourish and operate—including an appetite for new ideas, change, and risk; tolerance for failure; empowerment of individuals; and an orientation to the future. ARPA-E directors also engage externally to accomplish the program’s mission, with their role thereby extending to working with Congress and creating partnerships with other energy research programs, in addition to the role of serving as an exemplar and leader to ARPA-E staff.

Individuals also stated their belief that the ARPA-E director must be able to foster and maintain the trust of agency staff, especially the program directors, and of national leaders. The director must be widely recognized and respected as an accomplished scientist or engineer. This requirement was anticipated by ARPA-E’s authorizing legislation, which stipulates that the agency’s director is to be an individual who, “by reason of professional background and experience, is especially qualified to advise” the secretary of energy on “matters pertaining to long-term and high-risk barriers to the development of energy technologies.”6

Acknowledged technical competency and skill serve as a foundation for building trust that in turn enables empowerment and autonomy among program directors and other key personnel. Program directors must be able to trust that the director will engage with them regarding the technical details of proposed programs, as well as evaluation of which projects merit funding. While only the director is authorized to make funding decisions, program directors are the domain experts who serve as the heart of the merit review and decision-making processes. They want the director to be fully engaged and constructively supportive throughout those processes. Program directors consulted for this study said further that they wanted to know the director will trust them when they make recommendations to fund, redirect, and terminate projects.

Program Director Characteristics: Quantitative Analysis

Program directors arguably serve the most critical function at ARPA-E. They are chiefly responsible for serving as opportunity creators and idea harvesters, carrying out the vital efforts necessary to identify and support those researchers who are developing potentially disruptive ideas within an emerging

___________________

6 42 U.S.C. § 16538(d)(2).

technology field and have the ability to perform the research (Bonvillian and van Atta, 2011). Biographical research on ARPA-E program directors demonstrates that they all hold research doctorate degrees in science or engineering fields and are diverse in terms of career stage and professional background, but not gender. Program directors are overwhelmingly male.

For this analysis, the committee collected data on 32 program directors (29 males and 3 females). Using a career stage taxonomy, the committee found that the year in which program directors received their undergraduate degree ranged from 1971 to 2007. Taking date of undergraduate degree as a reasonable proxy for career stage, three categories were created: late career (undergraduate degree pre-1985), midcareer (undergraduate degree 1985–2000, inclusive), and early career (undergraduate degree post-2000). The data show that late-career program directors managed 43 percent of projects selected for funding, midcareer program directors 41 percent, and early-career program directors 16 percent. Using a professional background taxonomy, the prior careers of program directors who had held only academic jobs following attainment of their final degree were categorized as Academia, those with careers only in industry as Industry, and those that had held positions in both academic and industry settings as Blended. The Academia program directors accounted for 28 percent of the total, Industry program directors accounted for 34 percent, and Blended program directors for 38 percent. Of the 16 program directors who have departed ARPA-E, 4 have since had blended career paths, in this case meaning they have held positions in a combination of Academia, Industry, or Government since departing ARPA-E, 5 hold Academia positions, 2 still hold a position elsewhere in the federal government, and 5 are in Industry positions. These data are shown in Figure 3-1.

NOTES: This Sankey diagram presents the program directors’ careers before and after ARPA-E. For example, 11 program directors came from industry. N = 32.

Recruiting Program Directors

ARPA-E’s primary method of recruiting program directors is by word of mouth. Current and alumni program directors suggest individuals that ARPA-E may wish to consider, and they inform their professional networks of whether they think ARPA-E is a valuable place to work. While this process could not be observed for this study, committee members were able to observe some of ARPA-E’s efforts to recruit program directors. At five ARPA-E events—one workshop, three kickoff meetings, and the annual Energy Innovation Summit in 2016—committee members observed a similar recruiting pitch. At the workshop and kickoff meetings, the pitch was made at some point when all attendees were gathered and giving their attention to the speaker, the deputy director for technology. At the summit, the pitch was given during several of the scheduled sessions. The pitch consisted of the deputy director for technology informing the audience that ARPA-E is always seeking new program directors, asking anyone interested in applying to speak with him and/or send a resume, and asking anyone who knew of a potentially interested and qualified candidate to consider sending that person’s resume. ARPA-E’s website also lists program director as a current opening under the “job opportunities” link.7

Several former program directors presented information to the committee during open data gathering sessions. The committee also corresponded with several and consulted with others, and met with then-current program directors at ARPA-E events such as kickoff and annual meetings. Most program directors contacted for this study identified three common opportunities of serving as a program director that attracted them. First, they saw working at ARPA-E as presenting the chance to work with ideas and technologies that have the potential to be truly innovative. They found this as offering more chance to make a significant impact on the energy industry than working at some government research funding initiatives that they viewed as doing mostly incremental work and funding projects to develop well-known technologies along established roadmaps. They also contrasted ARPA-E with working in private industry, where research is focused on supporting existing product lines and over short time spans, leaving little chance to work on truly revolutionary ideas or technologies. Second, the research investment budgets that program directors must manage at ARPA-E—provided for establishing a focused technology program—are at least an order of magnitude greater than what they would expect to manage in private-sector settings. Even at the largest technology or venture capital firm, they reasonably would expect to be able to support 2 or 3 projects at a time; at ARPA-E, they could support roughly 20. On this scale, they believed they would have a real chance at making a significant technological impact in the sector. Third, the term-limited nature of the

___________________

7 As of May 15, 2017.

appointment meant that to make an impact, they would need to work hard on identifying and supporting promising ideas. They stated they found this a motivating factor, and contrasted it with the likelihood of building constituencies or maintaining independence from corporate or government bureaucracy that often accompanies long-term positions.

Although it could not draw any strong conclusions from these anecdotal observations, the committee found them enlightening and informative. A more systematic and in-depth analysis than was feasible during this study could make stronger conclusions. Given the descriptive statistics detailed above, however, many questions arise that either ARPA-E or an independent assessor would do well to attempt to answer. For instance, a review of the data on program director characteristics shows that fewer than 10 percent are or have been women. Whether this percentage is representative of the qualified talent pool available to ARPA-E or perhaps indicates some shortcoming in the agency’s recruiting efforts, at least as measured by gender diversity, would be important to ascertain. Assessing such questions would require an unbiased characterization of the available talent pool, e.g., persons of sufficient education, experience, and talent, to use as a basis of comparison with the pool of applicants for program director positions. It would also need to include examination of practices such as outbound and inbound recruiting, likely with comparisons with effective industry practices of other public and private employers. Regardless of how the analysis might be conducted or who would conduct it, it would need to be carried out with ARPA-E’s specific mission in mind, and with robust consideration of variables within ARPA-E’s control and what labor market variables are beyond the agency’s control.

Support of ARPA-E’s Innovation Culture by Technology-to-Market Personnel

Every ARPA-E project is assigned a team, including a technology-to-market (T2M) advisor tasked with providing performers with non-technical assistance to help them prepare for eventual transition of the technology from laboratory to market. Most ARPA-E T2M advisors began their careers with technical or science degrees, adding an MBA or business experience later. The agency’s goal is to attract personnel with direct technology experience who also have experience working with products and manufacturing so they can bring a supplemental, and sometimes different, perspective to bear on the thinking of the program directors. They work with performer teams to create technology-to-market milestones as part of award negotiation, and they work with the program directors to identify and encourage commercialization pathways during the award timeframe.

Given the long life spans of incumbent energy technologies, the relatively long timeframe and large amounts of capital required to adequately verify and validate new energy technologies and move them to commercial product development, there is an inherent tension between funding early-stage transformational technologies and bringing products to market quickly. It is

unreasonable to expect that a technology could move from concept to market within the 3-year (or less) timeframe of an ARPA-E project. There is also a risk of ARPA-E’s T2M team and the program directors becoming institutionally isolated from one another.

The committee was unable to conduct any quantitative analysis for T2M personnel as it did for program directors, but nonetheless was able to gather some qualitative data on these personnel, including their roles, functions, and activities. ARPA-E views its T2M activities as an ongoing experiment, and the challenge of developing such a program may be greater than originally thought. The T2M program was first created around 2011. At the time of this study the T2M program had 13 personnel and only a few alumni. Such a small sample could not be considered statistically representative, and any analysis would necessarily be subjective opinion.

In the evolution of T2M, ARPA-E needs to stay aware of two things. First, different performers have different needs. Small and young companies consulted for the case studies prepared for this assessment, especially those that spin out of university research, reported that T2M appears to work well (Appendix D). On the other hand, companies with marketing and commercialization experience reported that T2M provided little value to their projects (Appendix D). Second, technologies at different stages of development may have different T2M needs. For example, technologies at earlier stages of development could be burdened by milestones focused on attracting additional investment before project success is assured. One way to manage the inherent tension is to be aware of the different technology levels of different projects and stratify the T2M goals to match (Branz, 2015).

The committee recognizes the agency’s efforts to continuously evolve and improve its T2M efforts and encourages further evolution while cautioning against overexpansion. For example, ARPA-E should consider making full T2M plans optional—encouraging development of these plans by performers most likely to benefit, such as academics—but requiring performers to describe potential product applications if they can prove technological feasibility. It also could provide information or research to performers on critical nontechnical factors that could impact market adoption of future products, such as regulatory risk and other, common risks other than business market risks.

A deeper analysis of the roles of T2M advisors and impact of the T2M program may be of great value to ARPA-E. Such an analysis was infeasible for this assessment, however, because of ARPA-E’s youth.

Support of ARPA-E’s Innovation Culture by Other Personnel

ARPA-E has a variety of staff that provide technical and commercialization support to its personnel. For example, much like DARPA, ARPA-E uses SETA contracts for relevant technical and nontechnical expertise. An example is a contractual arrangement with Booz Allen Hamilton (Booz

Allen Hamilton, 2012). SETA contractors are intended to provide deep technical knowledge and also ensure smooth transitions when one program director’s term ends and a new program director takes over a program. Depending on the needs of the program director and the project, these contractors can play an active role in a project.

ARPA-E also runs a fellows program that is intended to bring people to the agency very early in their careers and immerse them in the funding of high-risk and potentially transformative energy projects. During their tenure, fellows are expected to conduct technical and financial analyses to identify potential new technological opportunities, develop content for technical and other events, make onsite visits to performers, and perform other activities the agency expects will help identify new technological ideas to pursue and make connections with experts across fields and disciplines (ARPA-E, n.d.-a). The fellows program could be a good recruiting path for finding program directors. In fact, the agency expects that some of the fellows will be ARPA-E program directors within 10–15 years.8

The committee was unable to gather any data or conduct any analysis for support personnel as it did for program directors and T2M advisors. One challenge is a concern that formally interviewing SETA contractors as part of an assessment may place them at risk of violating the prohibition on nongovernmental personnel representing the government.

Autonomy’s Importance for Effective Active Project Management

Providing autonomy for rapid learning and adaptation is a key element of active management within the DARPA tradition. Such practices align with evidence from the project management literature suggesting that allowing managers greater flexibility and autonomy in how they manage projects enables better outcomes from R&D. Uncertainty inherent in the innovation process reduces the real option value of an R&D effort, whereas extending the set of options available to a manager increases the option value (Huchzermeier and Loch, 2001). Similarly, Trigeorgis (1997) finds that the flexibility to adapt to new information improves the option value. Dixit and Pindyck (1994) show that efforts with more inherent uncertainty increase the value of managerial flexibility.

Research suggests there are two principal ways ARPA-E could empower its program directors and their technical staff with more flexibility to manage projects. First is to ensure that they have an adequate measure of autonomy (Amabile, 1998; Elkins and Keller, 2003; Ndubisi et al., 2015; West, 1990; Wynen et al., 2014). Autonomy is important because it provides flexibility in decision making, long known to be essential to promote innovation (Nelson,

___________________

8 Interview with Mark Johnson.

1962). This is because a decentralized decision process empowers researchers to adjust quickly to results, respond to learning, and move quickly toward more productive paths (Nelson, 1962). Later empirical research has continued to support this idea, including at public-sector agencies in Europe with characteristics quite similar to those of ARPA-E (Amabile, 1998; Elkins and Keller, 2003; West, 1990; Wynen et al., 2014). Essentially, effective active management requires that program directors have autonomy in how they undertake that active management.

Second, ARPA-E can provide its program directors with resources and support to serve as innovation champions—clever, big-thinking, and future-oriented individuals who can imagine the possibilities in an idea and, importantly, also mobilize the resources needed to “explore, research, and build on promising, but uncertain, future technologies” and ultimately bring them to life (Tellis et al., 2009, p. 8; also, Berry et al., 2006; Howell and Higgins, 1990; Makri et al., 2006; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, 2015; Zenger and Lazzarini, 2004).

Evidence of Autonomy in Project Selection: Quantitative Analysis

Accordingly, a central question posed to this committee was the extent to which ARPA-E has internalized active management practices similar to those utilized by DARPA in its selection, management, and oversight of projects. The committee sought evidence that ARPA-E followed such practices, and directed its consultants to construct a large set of ARPA-E data from anonymized information on all concept paper applications; full-proposal applications; review scores for all full proposals; binary project selection; quarterly progress reports for each project; and outcome metrics associated with each project, including patent applications, publications, and a series of indicators for market engagement (e.g., follow-on funding) (the outcome metrics are presented in Chapter 4). For analysis of project outcomes, the dataset was then limited to the 234 completed projects as of December 2015.9

One critical component of a program director’s job at ARPA-E is the design of a program and the cultivation of an applicant base for that program through engagement with experts in the field. As detailed in Chapter 2, the first step in the application process is the submission of concept papers. The dataset used for this analysis includes 10,227 concept paper submissions, 19 percent of whose authors were encouraged to submit a full application. The dataset used includes 2,335 submitted full applications,10 24 percent of which were selected

___________________

9 Data collection began in January 2016.

10 ARPA-E had initiated 471 projects by the end of 2015. Because the projects dataset was limited to completed projects, those projects that were active at the start of 2016 were excluded. The dataset then consisted of 234 projects with end dates on or before December 31, 2015.

for award negotiation. The overall selection rate resulting from this two-step application process was 5 percent.

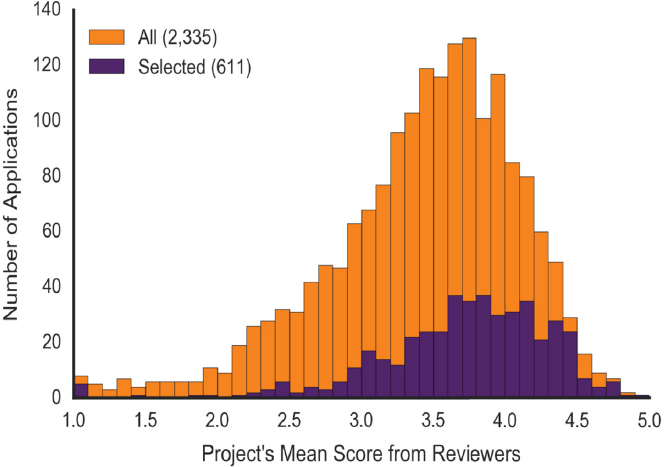

Comparing the mean overall scores among all selected applications with the full distribution of scores in Figure 3-2 shows that the selected applications are not differentiated by their scores. The mean overall score for selected projects was 3.7 out of 5, compared with 3.3 out of 5 for nonselected projects. Ranking the applications in order of mean overall score within a program shows that ARPA-E frequently selected applications from across the full range of scores rather than systematically selecting the projects with the highest reviewer scores.

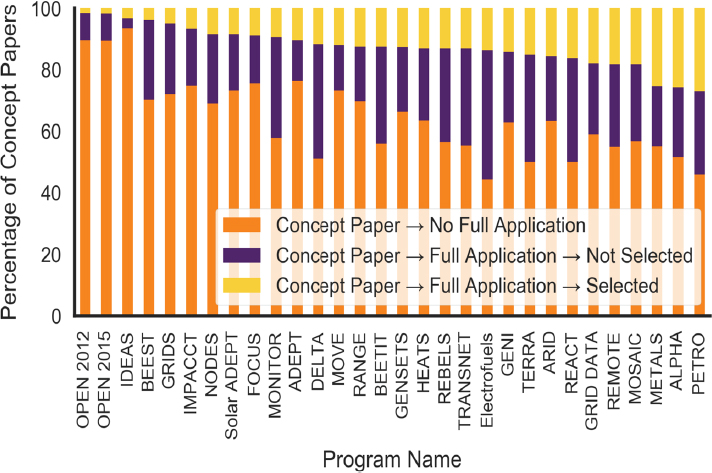

The selection rate varies significantly by program. OPEN programs receive more concept papers and full applications per available funding than focused programs. For OPEN programs,11 approximately 2 percent of the applicants that submit concept papers are eventually selected to negotiate for an award on average. Within the focused programs, on the other hand, approximately 11 percent of teams, on average, who submit a concept paper stage are eventually selected to negotiate for an award.12 These average selection rates, however, mask the wide variation across different programs, ranging from about 2 percent for the OPEN programs, to approximately 30

___________________

11 There is no data on concept papers from the first ARPA-E program, OPEN 2009.

12 Some FOAs requested full applications directly rather than soliciting concept papers as a first stage.

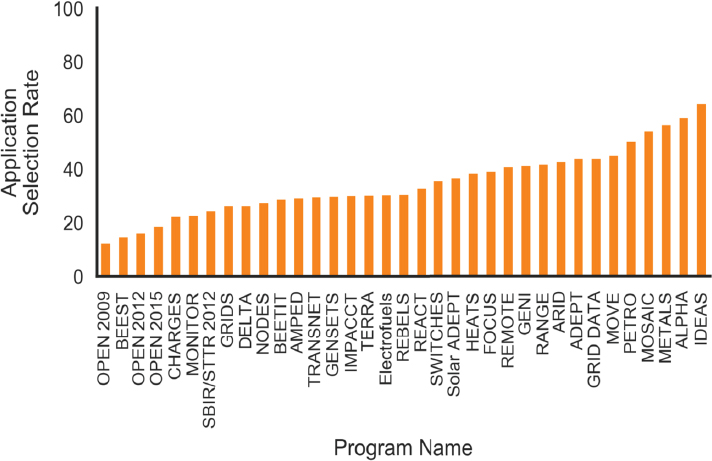

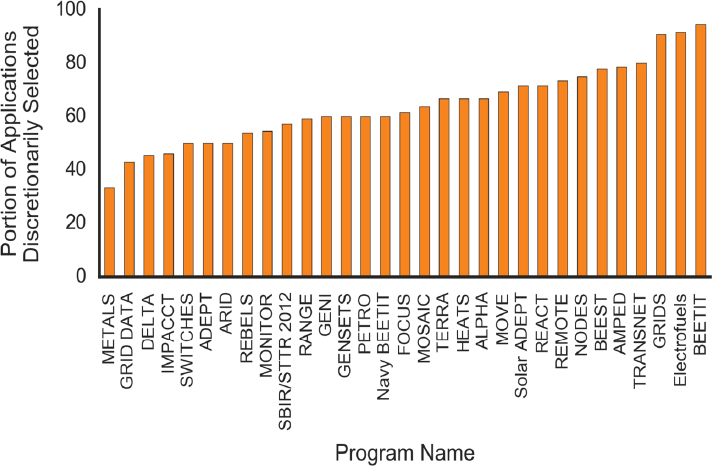

percent for some of the focused programs.13Figure 3-3 shows the selection rate from concept paper through full application and on to selection for award negotiation for many of the programs that the committee’s consultants were able to analyze. From full application to selection shows similar variation. The average selection rate for full applications is 24 percent, although the selection rate across programs ranges from 10 to 70 percent (see Figure 3-4).

As discussed in Chapter 2, at each step in the application process, external reviewers rate each application with respect to a variety of competencies, providing impact, merit, management, and overall ratings. The dataset for this analysis included reports for 1,800 of the 2,335 full applications. Each application had between 1 and 18 reviews, with a median of 3. Review scores ranged from 1 to 5, with a mean score of 3.4. However, there was wide variation in reviewer scores across many projects. For 20 percent of applications, the standard deviation for the overall score is greater than 1. Perhaps most interesting, the mean overall review score (or any other review category, for that

NOTES: Data are percentage of 10,227 concept papers submitted to ARPA-E through December 31, 2015, by program. The SHIELD program is not included since it did not require concept papers. See Appendix E for a list of program acronyms.

SOURCE: Goldstein and Kearney, 2016.

___________________

13 Navy BEETIT is not included because it is a specialized program not representative of typical application requirements. It was a specific program for the Navy.

NOTES: Data are percentage of 2,335 selected applications submitted to ARPA-E through December 31, 2015, by program. See Appendix E for a list of program acronyms.

SOURCE: Goldstein and Kearney, 2016.

matter) for each project had only a limited correlation with selection. This appears to support ARPA-E’s statements that scores play a limited role in selection. Increasing a project’s mean overall review score by a full point increased the likelihood of selection by only 20 percent. Moreover, holding mean overall review score constant, projects with a larger range of review scores were more likely to be selected. Given a constant perceived project capability, as shown by the average of reviewer scores, program directors were more likely to select those projects whose technical merit reviewers disagreed on, as shown by a larger spread between highest and lowest scores. This can be taken as evidence that ARPA-E is following its congressional mandate to identify and support projects with high potential for commercial and societal impact.

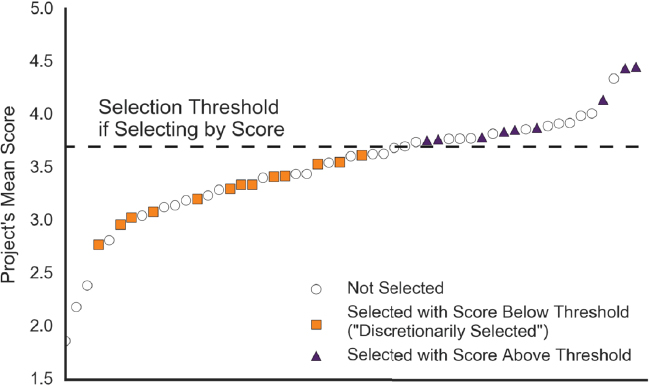

This analysis captures two important features of ARPA-E’s project management that point to autonomy for program directors and other key personnel. First, ARPA-E’s program directors have discretion to recommend projects for selection across the distribution of review scores according to their own discernment. The committee directed the consultants to create a counterfactual scenario whereby selection of projects for award negotiation was based solely on a numerical ranking of reviewer scores, with the highest-ranked projects being selected until the programs’ funds were exhausted. For the purposes of this analysis, it was convenient to label these latter projects as having been “discretionarily selected.” (See Box 3-1 for more detailed explanation of the process used for selecting which projects would be labeled as

“discretionarily selected” for this analysis.) Almost half (49 percent) of ARPA-E projects can be labeled as “discretionarily selected” using the definition and process described in Box 3-1, a finding that serves as strong evidence of program director discretion in recommending projects for funding and agency autonomy in the final selection of projects to fund.

Second, both selecting projects at the lower end of the review distribution and selecting projects that received a wider spread of reviewer scores are indicators of risk tolerance at ARPA-E, rather than peer review leading to regression to the mean. Program directors would be taking less risk if they made their funding recommendations by just picking the applications with the highest reviewer scores or based on reviewer consensus.

Figure 3-5 illustrates the degree to which program director discretion was used within the RANGE program, as measured by the large number of discretionarily selected projects. As seen in Figure 3-6, the proportion of discretionarily selected applications across focused technology programs ranges from approximately 30 percent to 91 percent. One possible interpretation of this range is that program director discretion is not applied uniformly across programs.

NOTE: Discretionarily selected projects are those that would not have been chosen using a simple ranking by reviewer score (see Box 3-1 for more detail).

SOURCE: Goldstein and Kearney, 2016.

NOTES: Discretionarily selected projects are those that would not have been chosen using a simple ranking by reviewer score (see Box 3-1 for more detail). See Appendix E for a list of program acronyms.

SOURCE: Goldstein and Kearney, 2016.

Recent research supports ARPA-E’s selection process as it balances the trade-off between valuable information to be gained and potential bias that comes with peer review. Reviewers may assign lower scores because of bias against novel ideas, the very thing ARPA-E needs to identify. A randomized controlled study found that “evaluators systematically give lower scores to research proposals that are closer to their own areas of expertise and to those that are highly novel,” with patterns consistent with “biases associated with boundedly rational evaluation of new ideas” and inconsistent with “intellectual distance simply contributing ‘noise’ or being associated with private interests of evaluators” (Boudrea et al., 2016, p. 2765). At the same time, peer review can still be of value. For instance, one study of National Institutes of Health (NIH) granting activity found a “one–standard deviation worse peer-review score among awarded grants [to be] associated with 15% fewer citations, 7% fewer publications, 19% fewer high-impact publications, and 14% fewer follow-on patents,” even with detailed controls for an investigator’s publication history, grant history, institutional affiliations, career stage, and degree types (Li and Agha, 2015). There is also evidence of the value of external information in making decisions. For instance, one study found that employees hired by manager discretion despite lower scores on a hiring test had lower retention rates than those who scored higher (Hoffman et al., 2015).

These findings appear to support ARPA-E’s decision to seek valuable information from peer reviewers while retaining program director discretion. The agency’s merit review process appears to account for possible biases in reviewer scores that can actually help with making the most use of them as one possible guide to locating truly novel ideas.

Performance of Discretionarily Selected Projects

Having determined that this discretion exists, a natural follow-up question arose regarding the performance of projects on the lower and upper ends of the review score distribution. Although the sample size of completed projects was too small for regression analysis, there has been no evidence to date that the discretion accorded to program directors results in poorer outcomes as a result of their selecting some projects with lower average review scores. It is possible that because discretionarily selected projects likely involve higher risk, their average performance over time will be similar to that of non–discretionarily selected projects. It is also possible, however, that over time, the distribution of outcomes may be wider, with more successful outliers—big winners—and more abject failures (i.e., the practice of promoting projects leads to a mean-preserving spread in outcomes). However, a larger dataset derived from a longer time series would be needed to observe this phenomenon, so that more time would have to pass for these dynamics to occur and be observable. Consequently, it would be useful to consider this possibility in future reviews of ARPA-E.

Active Project Management: Quantitative Evidence

Once projects have been selected for funding, each project team enters a negotiation phase with ARPA-E during which the parties agree upon financial terms and project-level milestones. Funding levels and project lengths vary significantly across projects. The award amount averages $2.3 million, with a maximum of $9.1 million. Initial project lengths vary from two quarters to 4 years. Also during the negotiation phase, the performer and program director agree on technical milestones and tasks. Once agreement has been reached on the funding level, timeline, and milestones, project work begins.

ARPA-E requires that performers submit status reports and meet with program directors on a quarterly basis. These interactions are not simply a formality—project direction, funding levels, and continuation are at stake each quarter. Program directors rate the progress of each project using stoplight colors (red, yellow, or green), and quarterly report data confirm that budgets, milestones, and project lengths are often modified. On average, budgets are increased by $0.2 million, and projects extended by 0.5 year. In some cases, though, projects are terminated early, as was the case for 25 of the 440 completed projects analyzed for this study.

Conversations with performer teams and with ARPA-E technical staff, including program directors and systems engineering and technical assistance (SETA) support staff, strongly suggest that a common component of active project management is to modify milestones in response to data generated through the course of a project. At least as often as each quarterly review, and often more frequently, project performer teams converse with the program director and his or her technical team. During these meetings, the performer teams provide data on progress toward meeting quarterly milestones. Rather than simply noting “yes, the milestone was met,” or “no, the milestone was not met,” the technical staff are trying to assess and understand what the project performer team has really learned. In a case where one or more milestones were not met, the program director attempts to work with the performer team to understand why. If it was not met because it was too technically ambitious, then performer and program director are likely to discuss modifying the milestone’s technical target, modifying its due date, or eliminating it if it is unlikely to be achievable during the life of the project. If milestones were met, the program director may investigate whether the milestones were not ambitious enough, perhaps modifying later milestones to be more technically ambitious or to be met earlier in the project’s life. Program directors and performers will also create new milestones in response to the feedback and data.

At least 45 percent of projects experience at least one milestone change. Likely this is an underestimate because the data available capture only deletion or creation of milestones during the project, and not a technical change or a due date change within a milestone. Support staff are responsible for coding changes into an administrative database. The database, however, lists only creations and deletions; there is no separate flag for modification. It is clear that sometimes

when a milestone was modified, the technical target was updated, but within the database the “old” milestone was not deleted and replaced with a “new” one incorporating the updated criteria.

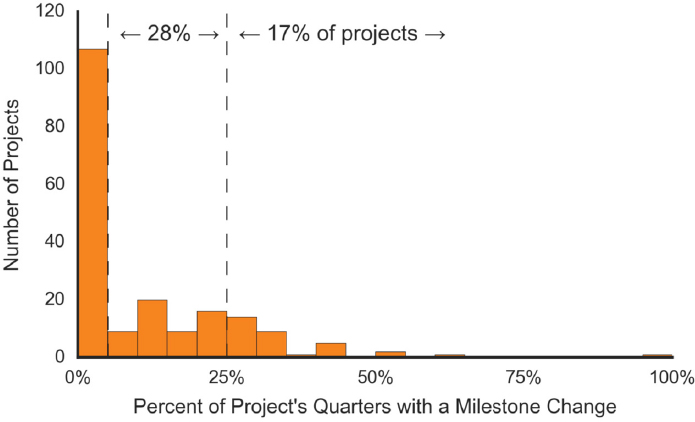

For this analysis, projects were further subdivided into two groups based on the percentage of measured quarters that involved milestone creation or deletion. Slightly more than one-fourth (28 percent) of projects had “infrequent” milestone changes (milestones changed in fewer than 25 percent of the measured quarters), and 17 percent had “frequent” milestone changes (milestones changed in 25 percent or more of the measured quarters, i.e., at least once per year). The distribution of projects among these groups is illustrated in Figure 3-7.

Project Assessment to Inform Active Management: Quantitative Assessment

Each quarter program directors rate projects according to how well they are meeting their milestones for technical, cost, schedule, and overall performance. In 2015 an additional milestone was added to track technology-to-market performance. (Technology-to-market advisors are discussed in the next section.) The ratings are given as either green, yellow, or red, where green means the project is on track and meeting milestones; yellow means the project has missed milestones but can recover; red means the project has missed significant (“go/no-go”) milestones and may not be able to recover. Examining the data on overall status for all project quarters, 55 percent of quarters were rated green, 38 percent yellow, and the remaining 7 percent red. Table 3-1 shows a transition matrix depicting the dynamics of changing colors from one

SOURCE: Goldstein and Kearney, 2016.

TABLE 3-1 Transition Matrix for Overall Status

| Statust+1 | |||||

| Status | Red | Yellow | Green | Total | |

| Statust | Red | 66% | 29% | 5% | 100% |

| Yellow | 8% | 71% | 21% | 100% | |

| Green | 1% | 21% | 78% | 100% | |

quarter to the next. The table reveals a high degree of rating persistence. Green ratings are especially stable (78 percent chance of persisting), followed by yellow (71 percent) and red (66 percent). Positive changes in status are relatively more likely than negative changes. For example, there is a 21 percent chance of a yellow status becoming green, compared with an 8 percent chance of a yellow status becoming red.

Considering the trajectory of projects through different status ratings, green ratings are seen to be frequent across the dataset. A majority of projects (88 percent) had at least one overall green quarter, and a majority (61 percent) never had a red quarter. Furthermore, 9 percent of projects were overall green for their entire duration. Focusing on the final quarter, all but three terminated projects ended with an overall red status, likely because the most common reason for early termination is failure to meet milestones. By comparison, a much smaller portion of projects that went full term ended on a red status. There were also some projects with consecutive red quarters that later changed status and were able to go to full term. One possible reading of these data is as additional evidence of program director discretion. For example, if ARPA-E had a bright line rule, say, requiring termination of any project with two consecutive red quarters, then it is possible that program directors would be required to terminate projects for nontechnical reasons such as a principal investigator’s suffering from an acute but short-term medical condition or a family emergency that temporarily slowed or halted work. But while the project management dashboard rating system is based on much information, it is still not the total picture of a given project. Thus, even in a situation where a project has successive red status quarters, the program director can determine whether there is a path for the project team to rectify whatever led to missing targets and still complete the project in good standing instead of recommending that the project be terminated. Such discretion can provide positive outcomes.

Goldstein and Kearney found a number of correlations between milestone changes and quarterly status ratings. Although it is difficult to determine whether or not the quarterly project status changes because of milestone changes, Goldstein and Kearney (2016) find that a “quarter in which a project is added or deleted, compared to a ‘red’ or ‘yellow’ quarter.” An analysis that could draw conclusions, rather than just correlations, regarding causation between milestone changes and quarterly status would require analyzing which milestones were changed, such as whether technical, cost, schedule, technology-to-market, or overall performance, and why the change was made. Although ARPA-E keeps

track of the category of milestone changed, to conduct this analysis they would also need to record systematically two other attributes of the milestone changes. First, there would need to be a detailed record of precisely why milestones were changed. Second, there would need to be a control group of some sort that could be used to build a counterfactual, but creating a control group for participants in a government program is extremely difficult.

Nonetheless, the data that are available regarding quarterly interactions illustrate an element of active project management within ARPA-E, capturing the hands-on nature of program directors’ engagement with each project and the project performer team. This is evidence that active program management is taking place and satisfying Congress’s requirement that program directors recommend restructuring or termination as needed.14 It also points to the third defining organizational feature of ARPA-E listed earlier: that active project management is important to ARPA-E.

Examining this body of evidence led to the identification of the second defining organizational feature of ARPA-E listed earlier: that ARPA-E program directors maintain significant autonomy and discretion in project selection and management.

Processes to Support a Culture of Innovation and Risk Taking

ARPA-E has in place a number of processes intended to support achieving its mission and goals. This section describes human resource processes for program directors and analyzes the impact of PD transitions. It also describes ARPA-E’s cost sharing requirements and processes for awards.

Program Director Transitions

Given the importance of the program director in shaping focused technology programs and managing projects, the committee investigated the potential for disruption when program directors change. Given program directors’ potential impact on projects, hiring top-tier talent is a necessity for the success of ARPA-E programs. The agency’s authorizing legislation set the standard term for program directors to 3 years, presumably seeking an appropriate balance for program directors who must weigh the prestige of being a program director against the forgone salary and career progression had they not taken a break from a nongovernmental position. Program directors spend the first 12 to 18 months of their tenure managing projects from existing programs following departure of another program director, designing programs, and soliciting projects. They spend the balance of their term managing the new projects created in their program, along with any other assigned projects. Since

___________________

14 42 U.S.C. § 16538(g)(2)(b) (2017).

project lengths typically range from 2 to 3 years, many projects will experience a change in program director.

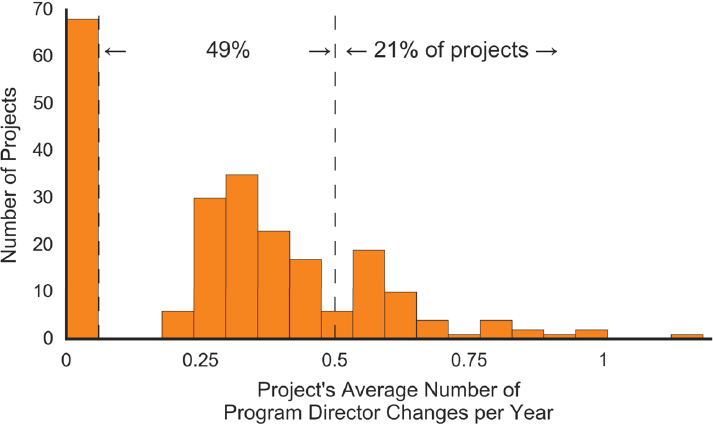

A majority of projects examined for this analysis (70 percent) experienced at least one program director change. The number of program director changes was 0.89 on average and the median was 1.0, meaning that the typical project experienced one such change. A measure of the rate of program director turnover was obtained by scaling the number of program director changes by the length of the project. The mean value for turnover was 0.3 changes per year, and the distribution among all projects is shown in Figure 3-8. Projects that experienced program director changes are divided into two groups: one with “low turnover,” which experienced at least 1.0 change but less than 0.5 change per year (49 percent of projects), and one with “high turnover,” defined as 0.5 change per year or more (21 percent of projects). The remaining 30 percent of projects did not experience a program director change.

One might expect that a program director transition could negatively impact a project through the loss of management continuity. Yet the committee found no evidence that projects have been harmed by such transitions, even after controlling for other variables. First, Goldstein and Kearney (2016) show that there is no significant relationship between program director transitions and ARPA-E’s internal metric of project success. In other words, after controlling for organization type, initial award amount, and initial project length, there is no relationship between a project’s having had at least one program director change and the project’s having been terminated early, ending up with a status of green (meeting all milestones), or ending up with a status of red (failed to meet milestones) (Goldstein and Kearney, 2016, Table 10). Furthermore, after

SOURCE: Goldstein and Kearney, 2016.

controlling for organization type, initial award amount, and initial project length, the likelihood of a project’s filing a patent application increased if the program director changed (Goldstein and Kearney, 2016, Table 17).

Cost Sharing

Congress mandated that ARPA-E’s program directors identify “innovative cost-sharing arrangements for ARPA-E projects.”15 Consequently, cost sharing is a requirement for obtaining an ARPA-E award, although a variety of waivers are available. One rationale for cost sharing is that it requires ARPA-E awardees to become financially invested in their projects. Another is that it allows leveraging of federal dollars; particularly for projects intended to lead to commercialization of the technology, it can help ensure the involvement of partners capable of moving products to market. Cost-sharing minimums vary depending on the requirements of the particular FOA, but are typically either 5 percent, 10 percent, or 20 percent if the project is awarded under a cooperative agreement or grant. If a project award is made through a technology investment agreement or an “other transaction” agreement, the minimum cost-sharing obligation is typically 50 percent of the total project cost.

The committee heard statements that cost sharing can be problematic, and some individuals stated that it acts as an impediment to the participation of national laboratories and small companies in ARPA-E programs and projects. Some present and former ARPA-E employees questioned the value of the cost-sharing component in the context of the ARPA-E model. One former program director observed that the intrinsic purpose of cost-sharing requirements is to leverage federal funds and to ensure that industry participants have genuine interest in conducting research in a given technology area. In contrast, another former program director stated the belief that cost sharing yields few benefits, has various unintended negative consequences, and may already be seen by private companies as a disincentive to applying for ARPA-E funding.16

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPACT 2005) provides authority for DOE, and thus ARPA-E, to modify or reduce cost-sharing requirements.17 For example, such modifications have also been adopted in the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), where an awardee can request a reduction in the cost share from 20 percent to 10 percent. Each of ARPA-E’s FOAs outlines cost-sharing requirements for project budgets, including the possibility of applying for a modification of those requirements.

___________________

15 42 U.S.C. § 16538(g)(2)(B)(v) (2017).

16 Presentation to the committee by Dane Boysen, December 8, 2015.

17 42 U.S. Code § 16352.

Comparisons to and Coordination with DARPA, Other Offices at DOE, and Other Federal Agencies

Because ARPA-E was patterned after DARPA, many of the agency’s processes have their origins at DARPA. While other DOE offices have utilized some processes and practices similar to those found at ARPA-E, since the agency’s creation, some offices have taken steps to adapt ARPA-E’s processes to their own contexts in a more systematic fashion.

Comparisons to DARPA

Many of ARPA-E’s attributes and processes were inspired by or borrowed from DARPA, although there are key differences as well. Both, for instance, are meant to be autonomous within their respective cabinet-level departments and feature relatively low levels of hierarchy. Other key areas of similarity include an organizational culture of risk taking, a focus on hiring highly qualified technical staff with academic and industrial backgrounds, and providing broad autonomy for program managers/directors to identify and support relevant technologies for specific purposes. There also are some important differences, though, in the agencies’ attributes and how they undertake their work.

The largest and most important difference is the size of each agency’s budget and the uncertainty surrounding whether it will be funded. The disparity in budgets leads to a number of critical differences in each agency’s overall approach to funding research. DARPA’s annual budget is roughly 10 times that of ARPA-E and, as part of the Department of Defense, is not under threat of being reduced to zero each year. This scale and certainty of funding allows DARPA to take a broad and long-range view and approach to supporting technology innovation that ARPA-E cannot take. This characteristic of DARPA manifests in several ways. First, the agency has always featured offices focused on specific technological areas. These offices are often organized with particular strategic initiatives in mind, and they are directed to create and fund programs that support over multiple decades the entire suite of technologies needed to provide platform support for the desired technological outcome rather than to fund individual technologies.

DARPA also has a long history of holding “summer studies” that bring together its program managers and leading scientists and engineers to study and review future research areas. Participants engage in activities aimed at fostering better understanding of current military challenges and establish task forces to focus on potential new directions and programs at DARPA that can help meet these challenges. Afterward, DARPA program managers continually engage with the research and innovation community, meeting with researchers and users to keep learning about emerging research, capabilities, and needs. They deliberately seek to direct research toward solving a challenge or creating a capability by seed-funding researchers working on common themes. They fund multiple, often competing or disconnected researchers with an aim of nudging

the research in a particular direction and increasing knowledge flow within the research community. DARPA’s offices will support activities and focused funding programs to pursue meeting a strategic challenge for as long as doing so makes sense, often for decades.

Many of these kinds of strategic activities would be difficult for ARPA-E to undertake because of its much smaller budget. As noted earlier, each year when new programs are funded, to mitigate the risk that its budget may be reduced to zero, ARPA-E obligates from that year’s appropriation the full amount of funding needed to create and fund its projects for their full duration, often 3 years. Coupled with its existential uncertainty, ARPA-E has little capacity to pursue the sorts of long-term strategic activities that DARPA undertakes as described above. Similarly, ARPA-E has yet to utilize such mechanisms as inducement prizes or grand challenges.

The agencies have quite similar approaches to reviewing applications and selecting projects for award negotiation. Both request pre-proposal submissions and then encourage some entrants to submit full applications. Both agencies ask that these submissions take the form, effectively, of a response to the Heilmeier Catechism.18 Both review full applications through program director/manager-driven processes. DARPA, however, does not utilize peer review in its process because of concerns that peer reviewer comments or scores tend to discount truly novel and potentially breakthrough ideas. ARPA-E’s merit review process, on the other hand, makes use of information from peer reviewers, especially written comments, although evidence presented in Figures 3-5 and 3-6 show that many projects are “discretionarily selected.”

Another area of commonality between ARPA-E and DARPA is making use of two different types of programs to fund research, ones focused on a specific technology or technology area, and so-called open announcements seeking any good idea that fits within the agency’s mission. There is a significant and technologically consequential difference in the way that each agency conducts its call for submissions. At DARPA, each program office has a standing announcement that is always available for submissions, even if the idea does not align with current technology-specific programs. This allows office directors and program managers to fund worthwhile ideas whenever an innovator is capable of submitting. ARPA-E’s OPEN FOAs, however, are offered only every 3 years and accept submissions for only a set period of time, usually about 90–120 days. Consequently, innovators who have an idea for a submission outside of that time window must wait until another OPEN FOA is announced, possibly as long as 3 years. It is unlikely that the ARPA-E could

___________________

18 The Heilmeier Catechism refers to a set of questions created by George H. Heilmeier, director of DARPA from 1975 to 1977, to help agency officials think through and evaluate proposed research programs.

adopt an open system like DARPA’s without a larger budget and less budgetary uncertainty.

Table 3-2 summarizes the most significant points of comparison between ARPA-E and DARPA.

TABLE 3-2 Comparison of Attributes of DARPA and ARPA-E

| Attribute | DARPA | ARPA-E |

|---|---|---|

| Agency Organization | ||

| Direct Report to Department Secretary | Yes | Yes |

| Flat Organizational Structure | Yes | Yes |

| Agency Features | ||

| Focused Mission | Yes: initiate rather than be the victim of strategic technological surprises | Yes, technologically narrower: overcome the long-term and high-risk technological barriers in the development of energy technologies |

| Budget Size | Approximately $3 billion/year | Approximately $280 million/year |

| Concentrated Primary Market | Yes: Department of Defense and prime contractors, but for many sectors no longer the dominant source of demand | No |

| Number of Program Managers | Nearly 100 | Approximately 15 |

| Term Appointments for Program Mangers | Yes, 3-5 years | Yes, 3 years |

| Culture an Important Feature to Support Mission Success | Yes | Yes |

| Technical Offices Focused on Relevant Technology Areas | Yes: office managers orchestrate a “pyramid of technologies” across programs | No: agency budget too small |

| Attribute | DARPA | ARPA-E |

|---|---|---|

| Set Aside Full Multiyear Project Funding in Year One | No: annual appropriations sufficiently certain to enable annual allocations | Yes: to mitigate uncertainty of future budgets |

| Procedures and Processes | ||

| Orchestration of Technology Directions | Yes: specific strategy for all office directors and program managers in support of achieving technical outcomes and agency mission | Aspirational, but not yet a specific strategy |

| Funding of Entire Platform of Technologies Necessary to Achieve Particular Goals | Yes | No: budget too small |

| Program Managers/Directors Have Autonomy in Funding Recommendations | Yes: no peer review | Yes: program directors utilize information from peer review, but are not obligated to follow score cutoff or “rack and stack” |

| Effort to Build New Research Communities | Yes: specific strategy for all office directors and program managers in support of achieving technical outcomes and agency mission; aim is to connect previously disconnected researchers to enable otherwise infeasible research | Unclear: at present, ad hoc with anecdotal evidence |

| Active Management of Projects | Yes | Yes: regular site visits, review of data with performers, suggestions regarding technical directions of research and project team |

| Go/No-Go Technical Milestones for Projects | Yes, but how much has varied by decade and program | Yes: legislatively required; quarterly review of progress toward achieving milestones and feasibility |

| Attribute | DARPA | ARPA-E |

|---|---|---|

| Program or Procedures to Ensure Awardees Plan/Prepare for Eventual Commercialization | Yes: focused on military application; Adaptive Execution Office seeks to accelerate transition from DARPA project to Defense Department capability; focus on commercializing for defense with increasing interest in dual-use potential; most applications envision some application of technology; expectation that good technologies and teams will find new funding sources to continue past DARPA granting period since “DARPA is not in the business of sustaining the technology” | Yes: specific program and personnel to assist awardees with orienting to eventual market entry, identifying commercial applications, and finding sources of funding to continue past ARPA-E award period |

| Intensive Gatherings of Entire Research and Innovation Community to Identify Priorities and Directions | Yes: intensive problem-focused gatherings of thought leaders to determine specific problems to solve | No |

| Inducement Prizes and Competitions, and Grand Challenges | Yes | No, presumably because of budget limitations |

| Program Features | ||

| Programs Focused on Specific Technical Outcomes with Measurable Goals | Yes | Yes |

| Broad Area or Open Programs to Capture Promising Ideas That Do Not Fit within Particular Focused Programs | Yes | Restricted: OPEN program is made available roughly every 3 years, with an application window of approximately 120 days |

| Attribute | DARPA | ARPA-E |

|---|---|---|

| Fund Competing Technologies Aimed at Solving the Same Problem | Yes | Yes |

| Project Management Features | ||

| Suggest Milestone Modifications Based on Findings from the Project | Yes | |

| Regular Contact with Research Teams | Yes | Yes, at least quarterly |

| Suggest Milestone Modifications Based on Findings from Other Projects across Program and Agency | Yes | |

| Suggest Teaming Partners | Yes | |

| Suggest Changes in Personnel or Subcontractors | Yes | |

Comparing ARPA-E’s Mission and Goals with Other DOE Research Offices and Programs