6

Motivation to Learn

Motivation is a condition that activates and sustains behavior toward a goal. It is critical to learning and achievement across the life span in both informal settings and formal learning environments. For example, children who are motivated tend to be engaged, persist longer, have better learning outcomes, and perform better than other children on standardized achievement tests (Pintrich, 2003). Motivation is distinguishable from general cognitive functioning and helps to explain gains in achievement independent of scores on intelligence tests (Murayama et al., 2013). It is also distinguishable from states related to it, such as engagement, interest, goal orientation, grit, and tenacity, all of which have different antecedents and different implications for learning and achievement (Järvelä and Renninger, 2014).

HPL I1 emphasized some key findings from decades of research on motivation to learn:

- People are motivated to develop competence and solve problems by rewards and punishments but often have intrinsic reasons for learning that may be more powerful.

- Learners tend to persist in learning when they face a manageable challenge (neither too easy nor too frustrating) and when they see the value and utility of what they are learning.

- Children and adults who focus mainly on their own performance (such as on gaining recognition or avoiding negative judgments) are

___________________

1 As noted in Chapter 1, this report uses the abbreviation “HPL I” for How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition (National Research Council, 2000).

-

less likely to seek challenges and persist than those who focus on learning itself.

- Learners who focus on learning rather than performance or who have intrinsic motivation to learn tend to set goals for themselves and regard increasing their competence to be a goal.

- Teachers can be effective in encouraging students to focus on learning instead of performance, helping them to develop a learning orientation.

In this chapter, we provide updates and additional elaboration on research in this area. We begin by describing some of the primary theoretical perspectives that have shaped this research, but our focus is on four primary influences on people’s motivation to learn. We explore research on people’s own beliefs and values, intrinsic motivation, the role of learning goals, and social and cultural factors that affect motivation to learn. We then examine research on interventions and approaches to instructional design that may influence motivation to learn, and we close with our conclusions about the implications of this research.

The research we discuss includes both laboratory and field research from multiple disciplines, such as developmental psychology, social psychology, education, and cognitive psychology.

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

Research on motivation has been strongly driven by theories that overlap and contain similar concepts. A comprehensive review of this literature is beyond the scope of this report, but we highlight a few key points. Behavior-based theories of learning, which conceptualized motivation in terms of habits, drives, incentives, and reinforcement schedules, were popular through the mid-20th century. In these approaches, learners were assumed to be passive in the learning process and research focused mainly on individual differences between people (e.g., cognitive abilities, drive for achievement). These differences were presumed to be fixed and to dictate learners’ responses to features in the learning environment (method of instruction, incentives, and so on) and their motivation and performance.

Current researchers regard many of these factors as important but have also come to focus on learners as active participants in learning and to pay greater attention to how learners make sense of and choose to engage with their learning environments. Cognitive theories, for example, have focused on how learners set goals for learning and achievement and how they maintain and monitor their progress toward those goals. They also consider how physical aspects of the learning environment, such as classroom structures (Ames, 1986) and social interactions (e.g., Gehlbach et al., 2016), affect learning through their impacts on students’ goals, beliefs, affect, and actions.

Motivation is also increasingly viewed as an emergent phenomenon, meaning it can develop over time and change as a result of one’s experiences with learning and other circumstances. Research suggests, for example, that aspects of the learning environment can both trigger and sustain a student’s curiosity and interest in ways that support motivation and learning (Hidi and Renninger, 2006).

A key factor in motivation is an individual’s mindset: the set of assumptions, values, and beliefs about oneself and the world that influence how one perceives, interprets, and acts upon one’s environment (Dweck, 1999). For example, a person’s view as to whether intelligence is fixed or malleable is likely to link to his views of the malleability of his own abilities (Hong and Lin-Siegler, 2012). As we discuss below, learners who have a fixed view of intelligence tend to set demonstrating competence as a learning goal, whereas learners who have an incremental theory of intelligence tend to set mastery as a goal and to place greater value on effort. Mindsets develop over time as a function of learning experiences and cultural influences. Research related to mindsets has focused on patterns in how learners construe goals and make choices about how to direct attention and effort. Some evidence suggests that it is possible to change students’ self-attributions so that they adopt a growth mindset, which in turn improves their academic performance (Blackwell et al., 2007).

Researchers have also tried to integrate the many concepts that have been introduced to explain this complex aspect of learning in order to formulate a more comprehensive understanding of motivational processes and their effects on learning. For example, researchers who study psychological aspects of motivation take a motivational systems perspective, viewing motivation as a set of psychological mechanisms and processes, such as those related to setting goals, engagement in learning, and use of self-regulatory strategies (Kanfer, 2015; Linnenbrink-Garcia and Patall, 2016; Yeager and Walton, 2011).

LEARNERS’ BELIEFS AND VALUES

Learners’ ideas about their own competence, their values, and the preexisting interests they bring to a particular learning situation all influence motivation.

Self-Efficacy

When learners expect to succeed, they are more likely to put forth the effort and persistence needed to perform well. Self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1977), which is incorporated into several models of motivation and learning, posits that the perceptions learners have about their competency or capabilities are critical to accomplishing a task or attaining other goals (Bandura, 1977).

According to self-efficacy theory, learning develops from multiple sources, including perceptions of one’s past performance, vicarious experiences, performance feedback, affective/physiological states, and social influences. Research on how to improve self-efficacy for learning has shown the benefits of several strategies for strengthening students’ sense of their competence for learning, including setting appropriate goals and breaking down difficult goals into subgoals (Bandura and Schunk, 1981) and providing students with information about their progress, which allows them to attribute success to their own effort (Schunk and Cox, 1986). A sense of competence may also foster interest and motivation, particularly when students are given the opportunity to make choices about their learning activities (Patall et al., 2014).

Another important aspect of self-attribution involves beliefs about whether one belongs in a particular learning situation. People who come from backgrounds where college attendance is not the norm may question whether they belong in college despite having been admitted. Students may misinterpret short-term failure as reflecting that they do not belong, when in fact short-term failure is common among all college students. These students experience a form of stereotype threat, where prevailing cultural stereotypes about their position in the world cause them to doubt themselves and perform more poorly (Steele and Aronson, 1995).

A recent study examined interventions designed to boost the sense of belonging among African American college freshmen (Walton and Cohen, 2011). The researchers compared students who did and did not encounter survey results ostensibly collected from more senior college students, which indicated that most senior students had worried about whether they belonged during their first year of college but had become more confident over time. The students who completed the activity made significant academic gains, and the researchers concluded that even brief interventions can help people overcome the bias of prior knowledge by challenging that knowledge and supporting a new perspective.

Another approach to overcoming the bias of knowledge is to use strategies that can prevent some of the undesirable consequences of holding negative perspectives. One such strategy is to support learners in trying out multiple ideas before settling on the final idea. In one study, for example, researchers asked college students either to design a Web page advertisement for an online journal and then refine it several times or to create several separate ones (Dow et al., 2010). The researchers posted the advertisements and assessed their effectiveness both by counting how many clicks each generated and by asking experts in Web graphics to rate them. The authors found that the designs developed separately were more effective and concluded that when students refined their initial designs, they were trapped by their initial decisions. The students who developed separate advertisements explored the possibilities more thoroughly and had more ideas to choose from.

Values

Learners may not engage in a task or persist with learning long enough to achieve their goals unless they value the learning activities and goals. Expectancy-value theories have drawn attention to how learners choose goals depending on their beliefs about both their ability to accomplish a task and the value of that task. The concept of value encompasses learners’ judgments about (1) whether a topic or task is useful for achieving learning or life goals, (2) the importance of a topic or task to the learner’s identity or sense of self, (3) whether a task is enjoyable or interesting, and (4) whether a task is worth pursuing (Eccles et al., 1983; Wigfield and Eccles, 2000).

Research with learners of various ages supports the idea that those who expect to succeed at a task exert more effort and have higher levels of performance (Eccles and Wigfield, 2002). However, some studies have suggested that task valuation seems to be the strongest predictor of behaviors associated with motivation, such as choosing topics and making decisions about participation in training (Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2008). Such research illustrates one of the keys to expectancy-value theory: the idea that expectancy and value dimensions work together. For example, a less-than-skilled reader may nevertheless approach a difficult reading task with strong motivation to persist in the task if it is interesting, useful, or important to the reader’s identity (National Research Council, 2012c). As learners experience success at a task or in a domain of learning, such as reading or math, the value they attribute to those activities can increase over time (Eccles and Wigfield, 2002).

Interest

Learners’ interest is an important consideration for educators because they can accommodate those interests as they design curricula and select learning resources. Interest is also important in adult learning in part because students and trainees with little interest in a topic may show higher rates of absenteeism and lower levels of performance (Ackerman et al., 2001).

Two forms of learner interest have been identified. Individual or personal interest is viewed as a relatively stable attribute of the individual. It is characterized by a learner’s enduring connection to a domain and willingness to re-engage in learning in that domain over time (Schiefele, 2009). In contrast, situational interest refers to a psychological state that arises spontaneously in response to specific features of the task or learning environment (Hidi and Renninger, 2006). Situational interest is malleable, can affect student engagement and learning, and is influenced by the tasks and materials educators use or encourage (Hunsu et al., 2017). Practices that engage students and influence their attitudes may increase their personal interest and intrinsic motivation over time (Guthrie et al., 2006).

Sometimes the spark of motivation begins with a meaningful alignment of student interest with an assignment or other learning opportunity. At other times, features of the learning environment energize a state of wanting to know more, which activates motivational processes. In both cases, it is a change in mindset and goal construction brought about by interest that explains improved learning outcomes (Barron, 2006; Bricker and Bell, 2014; Goldman and Booker, 2009). For instance, when learner interest is low, students may be less engaged and more likely to attend to the learning goals that require minimal attention and effort.

Many studies of how interest affects learning have included measures of reading comprehension and text recall. This approach has allowed researchers to assess the separate effects of topic interest and interest in a specific text on how readers interact with text, by measuring the amount of time learners spend reading and what they learn from it. Findings from studies of this sort suggest that educators can foster students’ interest by selecting resources that promote interest, by providing feedback that supports attention (Renninger and Hidi, 2002), by demonstrating their own interest in a topic, and by generating positive affect in learning contexts (see review by Hidi and Renninger, 2006).

This line of research has also suggested particular characteristics of texts that are associated with learner interest. For example, in one study of college students, five characteristics of informational texts were associated with both interest and better recall: (1) the information was important, new, and valued; (2) the information was unexpected; (3) the text supported readers in making connections with prior knowledge or experience; (4) the text contained imagery and descriptive language; and (5) the author attempted to relate information to readers’ background knowledge using, for example, comparisons and analogies (Wade et al., 1999). The texts that students viewed as less interesting interfered with comprehension in that they, for example, offered incomplete or shallow explanations, contained difficult vocabulary, or lacked coherence.

A number of studies suggest that situational interest can be a strong predictor of engagement, positive attitudes, and performance, including a study of students’ essay writing (Flowerday et al., 2004) and other research (e.g., Alexander and Jetton, 1996; Schraw and Lehman, 2001). These studies suggest the power of situational interest for engaging students in learning, which has implications for the design of project-based or problem-based learning. For example, Hoffman and Haussler (1998) found that high school girls displayed significantly more interest in the physics related to the working of a pump when the mechanism was put into a real-world context: the use of a pump in heart surgery.

The perception of having a choice may also influence situational interest and engagement, as suggested by a study that examined the effects of classroom practices on adolescents enrolled in a summer school science course

(Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2013). The positive effect learners experience as part of interest also appears to play a role in their persistence and ultimately their performance (see, e.g., Ainley et al., 2002).

Intrinsic Motivation

Self-determination theory posits that behavior is strongly influenced by three universal, innate, psychological needs—autonomy (the urge to control one’s own life), competence (the urge to experience mastery), and psychological relatedness (the urge to interact with, be connected to, and care for others). Researchers have linked this theory to people’s intrinsic motivation to learn (Deci and Ryan, 1985, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Intrinsic motivation is the experience of wanting to engage in an activity for its own sake because the activity is interesting and enjoyable or helps to achieve goals one has chosen. From the perspective of self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000), learners are intrinsically motivated to learn when they perceive that they have a high degree of autonomy and engage in an activity willingly, rather than because they are being externally controlled. Learners who are intrinsically motivated also perceive that the challenges of a problem or task are within their abilities.

External Rewards

The effect of external rewards on intrinsic motivation is a topic of much debate. External rewards can be an important tool for motivating learning behaviors, but some argue that such rewards are harmful to intrinsic motivation in ways that affect persistence and achievement.

For example, some research suggests that intrinsic motivation to persist at a task may decrease if a learner receives extrinsic rewards contingent on performance. The idea that extrinsic rewards harm intrinsic motivation has been supported in a meta-analysis of 128 experiments (Deci et al., 1999, 2001). One reason proposed for such findings is that learners’ initial interest in the task and desire for success are replaced by their desire for the extrinsic reward (Deci and Ryan, 1985). External rewards, it is argued, may also undermine the learner’s perceptions of autonomy and control.

Other research points to potential benefits. A recent field study, for example, suggests that incentives do not always lead to reduced engagement after the incentive ends (Goswami and Urminsky, 2017). Moreover, in some circumstances external rewards such as praise or prizes can help to encourage engagement and persistence, and they may not harm intrinsic motivation over the long term, provided that the extrinsic reward does not undermine the individual’s sense of autonomy and control over her behavior (see National Research Council, 2012c, pp. 143–145; also see Cerasoli et al.,

2016; Vansteenkiste et al., 2009). Thus, teaching strategies that use rewards to capture and stimulate interest in a topic (rather than to drive compliance), that provide the student with encouragement (rather than reprimands), and that are perceived to guide student progress (rather than just monitor student progress) can foster feelings of autonomy, competence, and academic achievement (e.g., Vansteenkist et al., 2004). Praise is important, but what is praised makes a difference (see Box 6-1).

Other work (Cameron et al., 2005) suggests that when rewards are inherent in the achievement itself—that is, when rewards for successful completion of a task include real privileges, pride, or respect—they can spur intrinsic motivation. This may be the case, for example, with videogames in which individuals are highly motivated to play well in order to move to the next higher level. This may also be the case when learners feel valued and respected for their demonstrations of expertise, as when a teacher asks a student who correctly completed a challenging homework math problem to explain his solution to the class. Extrinsic rewards support engagement sufficient for learning, as shown in one study in which rewards were associated with enhanced memory consolidation but only when students perceived the material to be boring (Murayama and Kuhbandner, 2011). Given the prevalence

BOX 6-1 What You Praise Makes a Difference

of different performance-based incentives in classrooms (e.g., grades, prizes), a better, more integrated understanding is needed of how external rewards may harm or benefit learners’ motivation in ways that matter to achievement and performance in a range of real-world conditions across the life span.

Effects of Choice

When learners believe they have control over their learning environment, they are more likely to take on challenges and persist with difficult tasks, compared with those who perceive that they have little control (National Research Council, 2012c). Evidence suggests that the opportunity to make meaningful choices during instruction, even if they are small, can support autonomy, motivation, and ultimately, learning and achievement (Moller et al., 2006; Patall et al., 2008, 2010).2

Choice may be particularly effective for individuals with high initial interest in the domain, and it may also generate increased interest (Patall, 2013). One possible reason why exercising choice seems to increase motivation is that the act of making a choice induces cognitive dissonance: a feeling of being uncomfortable and unsure about one’s decision. To reduce this feeling, individuals tend to change their preferences to especially value and become interested in the thing they chose (Izuma et al., 2010). Knowing that one has made a choice (“owning the choice”) can protect against the discouraging effects of negative feedback during the learning process, an effect that has been observed at the neurophysiological level (Murayama et al., 2015). The perception of choice also may affect learning by fostering situational interest and engagement (Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2013).

THE IMPORTANCE OF GOALS

Goals—the learner’s desired outcomes—are important for learning because they guide decisions about whether to expend effort and how to direct attention, foster planning, influence responses to failure, and promote other behaviors important for learning (Albaili, 1998; Dweck and Elliot, 1983; Hastings and West, 2011).

Learners may not always be conscious of their goals or of the motivation processes that relate to their goals. For example, activities that learners perceive as enjoyable or interesting can foster engagement without the learner’s

___________________

2 The 2008 study was a meta-analysis, so the study populations are not described. The 2010 study included a total of 207 (54% female) high school students from ninth through twelfth grade. A majority (55.5%) of the students in these classes were Caucasian, 28 percent were African American, 7 percent were Asian, 3 percent were Hispanic, 1.5 percent were Native American, and 5 percent were of other ethnicities.

conscious awareness. Similarly, activities that learners perceive as threatening to their sense of competence or self-esteem (e.g., conditions that invoke stereotype threat, discussed below3) may reduce learners’ motivation and performance even (and sometimes especially) when they intend to perform well.

HPL I made the point that having clear and specific goals that are challenging but manageable has a positive effect on performance, and researchers have proposed explanations. Some have focused on goals as motives or reasons to learn (Ames and Ames, 1984; Dweck and Elliott, 1983; Locke et al., 1981; Maehr, 1984; Nicholls, 1984). Others have noted that different types of goals, such as mastery and performance goals, have different effects on the cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes that underlie learning as well as on learners’ outcomes (Ames and Archer, 1988; Covington, 2000; Dweck, 1986). Research has also linked learners’ beliefs about learning and achievement, or mindsets, with students’ pursuit of specific types of learning goals (Maehr and Zusho, 2009). The next section examines types of goals and research on their influence.

Types of Goals

Researchers distinguish between two main types of goals: mastery goals, in which learners focus on increasing competence or understanding, and performance goals, in which learners are driven by a desire to appear competent or outperform others (see Table 6-1). They further distinguish between performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals (Senko et al., 2011). Learners who embrace performance-avoidance goals work to avoid looking incompetent or being embarrassed or judged as a failure, whereas those who adopt performance-approach goals seek to appear more competent than others and to be judged socially in a favorable light. Within the category of performance-approach goals, researchers have identified both self-presentation goals (“wanting others to think you are smart”) and normative goals (“wanting to outperform others”) (Hulleman et al., 2010).

Learners may simultaneously pursue multiple goals (Harackiewicz et al., 2002; Hulleman et al., 2008) and, depending on the subject area or skill domain, may adopt different achievement goals (Anderman and Midgley, 1997). Although students’ achievement goals are relatively stable across the school years, they are sensitive to changes in the learning environment, such as moving from one classroom to another or changing schools (Friedel et al., 2007). Learning environments differ in the learning expectations, rules, and

___________________

3 When an individual encounters negative stereotypes about his social identity group in the context of a cognitive task, he may underperform on that task; this outcome is attributed to stereotype threat (Steele, 1997).

TABLE 6-1 Mindsets, Goals, and Their Implications for Learning

| Mindsets | |

| Fixed mindset—you are born with a certain amount of intelligence | Growth mindset—intelligence can be acquired through hard work |

| Goals | |

| Performance goal—works to look good in comparison to others | Mastery goal—works to learn/master the material or skill |

| Learning Behaviors | |

| Avoids challenges—prioritizes areas of high competence | Rises to challenges—prioritizes areas of new knowledge |

| Quits in response to failure—expends less effort | Tries harder in response to failure—puts forth more effort |

| Pursues opportunities to bolter self-esteem—seeks affirming social comparisons | Pursues opportunities to learn more—seeks more problem-solving strategies |

structure that apply, and as a result, students may shift their goal orientation to succeed in the new context (Anderman and Midgley, 1997).

Dweck (1986) argued that achievement goals reflect learners’ underlying theories of the nature of intelligence or ability: whether it is fixed (something with which one is born) or malleable. Learners who believe intelligence is malleable, she suggested, are predisposed toward adopting mastery goals, whereas learners who believe intelligence is fixed tend to orient toward displaying competence and adopting performance goals (Burns and Isbell, 2007; Dweck, 1986; Dweck and Master, 2009; Mangels et al., 2006). Table 6-1 shows how learners’ mindsets can relate to their learning goals and behaviors.

Research in this area suggests that learners who strongly endorse mastery goals tend to enjoy novel and challenging tasks (Pintrich, 2000; Shim et al., 2008; Witkow and Fuligni, 2007; Wolters, 2004), demonstrate a greater willingness to expend effort, and engage higher-order cognitive skills during learning (Ames, 1992; Dweck and Leggett, 1988; Kahraman and Sungur, 2011; Middleton and Midgley, 1997). Mastery students are also persistent—even in the face of failure—and frequently use failure as an opportunity to seek feedback and improve subsequent performance (Dweck and Leggett, 1988).

Learners’ mastery and performance goals may also influence learning and achievement through indirect effects on cognition. Specifically, learners with mastery goals tend to focus on relating new information to existing knowledge as they learn, which supports deep learning and long-term memory for the

information. By contrast, learners with performance goals tend to focus on learning individual bits of information separately, which improves speed of learning and immediate recall but may undermine conceptual learning and long-term recall. In this way, performance goals tend to support better immediate retrieval of information, while mastery goals tend to support better long-term retention (Crouzevialle and Butera, 2013). Performance goals may in fact undermine conceptual learning and long-term recall. When learners with mastery goals work to recall a previously learned piece of information, they also activate and strengthen memory for the other, related information they learned. When learners with performance goals try to recall what they learned, they do not get the benefit of this retrieval-induced strengthening of their memory for other information (Ikeda et al., 2015).

Two studies with undergraduate students illustrate this point. Study participants who adopted performance goals were found to be concerned with communicating competence, prioritizing areas of high ability, and avoiding challenging tasks or areas in which they perceived themselves to be weaker than others (Darnon et al., 2007; Elliot and Murayama, 2008). These students perceived failure as a reflection of their inability and typically responded to failure with frustration, shame, and anxiety. These kinds of performance-avoidance goals have been associated with maladaptive learning behaviors including task avoidance (Middleton and Midgley, 1997; sixth-grade students), reduced effort (Elliot, 1999), and self-handicapping (Covington, 2000; Midgley et al., 1996).

The adoption of a mastery goal orientation to learning is likely to be beneficial for learning, while pursuit of performance goals is associated with poor learning-related outcomes. However, research regarding the impact of performance goals on academic outcomes has yielded mixed findings (Elliot and McGregor, 2001; Midgley et al., 2001). Some researchers have found positive outcomes when learners have endorsed normative goals (a type of performance goal) (Covington, 2000; Linnenbrink, 2005). Others have found that achievement goals do not have a direct effect on academic achievement but operate instead through the intermediary learning behaviors described above and through self-efficacy (Hulleman et al., 2010).

Influence of Teachers on Learners’ Goals

Classrooms can be structured to make particular goals more or less salient and can shift or reinforce learners’ goal orientations (Maehr and Midgley, 1996). Learners’ goals may reflect the classroom’s goal structure or the values teachers communicate about learning through their teaching practices (e.g., how the chairs are set up or whether the teacher uses cooperative learning groups) (see Kaplan and Midgley, 1999; Urdan et al., 1998). When learners perceive mastery goals are valued in the classsroom, they are more likely

TABLE 6-2 Achievement Goals and Classroom Climate

| Climate Dimension | Mastery Goal | Performance Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Success Defined as… | Improvement, progress | High grades, high normative performance |

| Value Placed on… | Effort/learning | Normatively high ability |

| Reasons for Satisfaction… | Working hard, challenge | Doing better than others |

| Teacher Oriented toward… | How students are learning | How students are performing |

| View of Errors/Mistakes… | Part of learning | Anxiety eliciting |

| Focus of Attention… | Process of learning | Own performance relative to others |

| Reasons for Effort… | Learning something new | High grades, performing better than others |

| Evaluation Criteria… | Absolute, progress | Normative |

SOURCE: Adapted from Ames and Archer (1988, Tbl. 1, p. 261).

to use information-processing strategies, self-planning, and self-monitoring strategies (Ames and Archer, 1988; Schraw et al., 1995). A mastery-oriented structure in the classroom is positively correlated with high academic competency and negatively related to disruptive behaviors. Further, congruence in learners’ perceptions of their own and their school’s mastery orientation is associated with positive academic achievement and school well-being (Kaplan and Maehr, 1999).

Teachers can influence the goals learners adopt during learning, and learners’ perceptions of classroom goal structures are better predictors of learners’ goal orientations than are their perceptions of their parents’ goals. Perceived classroom goals are also strongly linked to learners’ academic efficacy in the transition to middle school. Hence, classroom goal structures are a particularly important target for intervention (Friedel et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2010). Table 6-2 summarizes a longstanding view of how the prevailing classroom goal structure—oriented toward either mastery goals or performance goals—affects the classroom climate for learning. However, more experimental research is needed to determine whether interventions designed to influence such mindsets benefit learners.

Learning Goals and Other Goals

Academic goals are shaped not only by the immediate learning context but also by the learners’ goals and challenges, which develop and change

throughout the life course. Enhancing a person’s learning and achievement requires an understanding of what the person is trying to achieve: what goals the individual seeks to accomplish and why. However, it is not always easy to determine what goals an individual is trying to achieve because learners have multiple goals and their goals may shift in response to events and experiences. For example, children may adopt an academic goal as a means of pleasing parents or because they enjoy learning about a topic, or both. Teachers may participate in an online statistics course in order to satisfy job requirements for continuing education or because they view mastery of the topic as relevant to their identity as a teacher, or both.

At any given time, an individual holds multiple goals related to achievement, belongingness, identity, autonomy, and sense of competence that are deeply personal, cultural, and subjective. Which of these goals becomes salient in directing behavior at what times depends on the way the individual construes the situation. During adolescence, for example, social belongingness goals may take precedence over academic achievement goals: young people may experience greater motivation and improved learning in a group context that fosters relationships that serve and support achievement. Over the life span, academic achievement goals also become linked to career goals, and these may need to be adapted over time. For example, an adolescent who aspires to become a physician but who continually fails her basic science courses may need to protect her sense of competence by either building new strategies for learning science or revising her occupational goals.

A person’s motivation to persist in learning in spite of obstacles and setbacks is facilitated when goals for learning and achievement are made explicit, are congruent with the learners’ desired outcomes and motives, and are supported by the learning environment, as judged by the learner; this perspective is illustrated in Box 6-2.

Future Identities and Long-Term Persistence

Long-term learning and achievement tend to require not only the learner’s interest, but also prolonged motivation and persistence. Motivation to persevere may be strengthened when students can perceive connections between their current action choices (present self) and their future self or possible future identities (Gollwitzer et al., 2011; Oyserman et al., 2015). The practice of displaying the names and accomplishments of past successful students is one way educators try to help current students see the connection.

Researchers have explored the mechanisms through which such experiences affect learning. Some neurobiological evidence, for example, suggests that compelling narratives that trigger emotions (such as admiration elicited by a story about a young person who becomes a civil rights leader for his community) may activate a mindset focused on a “possible future” or values

BOX 6-2 Learners’ Perceptions of the Learning Environment Can Inadvertently Undermine Motivation

(Immordino-Yang et al., 2009). Similar research also points to an apparent shifting between two distinct neural networks that researchers have associated with an “action now” mindset (with respect to the choices and behaviors for executing a task during learning) and a “possible future/values oriented”

mindset (with respect to whether difficult tasks are ones that “people like me” do) (Immordino-Yang et al., 2012). Students who shift between these two mindsets may take a reflective stance that enables them to inspire themselves and to persist and perform well on difficult tasks to attain future goals (Immordino-Yang and Sylvan, 2010).

Practices that help learners recognize the motivational demands required and obstacles to overcome for achieving desired future outcomes also may support goal attainment, as suggested in one study of children’s attempts to learn foreign-language vocabulary words (Gollwitzer et al., 2011). Research is needed, however, to better establish the efficacy of practices designed to shape learners’ thinking about future identities and persistence

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON MOTIVATION

All learners’ goals emerge in a particular cultural context. As discussed in Chapter 2, the way individuals perceive and interpret the world and their own role in it, and their expectations about how people function socially, reflect the unique set of influences they have experienced. The procedures people use to complete tasks and solve problems, as well as the social emotional dispositions people bring to such tasks, are similarly shaped by context and experience (Elliott et al., 2001; Oyserman, 2011). In this section, the committee discusses three specific lines of research that illustrate the importance of culturally mediated views of the self and social identities to learners’ perceptions of learning environments, goals, and performance.

Cross-Cultural Differences in Learners’ Self-Construals

Over the past several decades, researchers have attempted to discern the influence of culture on a person’s self-construal, or definition of herself in reference to others. In an influential paper, Markus and Kitayama (1991) distinguished between independent and interdependent self-construals and proposed that these may be associated with individualistic or collectivistic goals. For example, they argued that East Asian cultures tend to emphasize collectivistic goals, which promote a comparatively interdependent self-construal in which the self is experienced as socially embedded and one’s accomplishments are tied to the community. In contrast, they argued, the prevailing North American culture tends to emphasize individualistic goals and an individualistic self-construal that prioritizes unique traits, abilities, and accomplishments tied to the self rather than to the community.

Although assigning cultural groups to either a collectivist or individualistic category oversimplifies very complex phenomena, several large-sample

survey studies have offered insights about the ways learners who fit these two categories tend to vary in their assessment of goals, the goals they see as relevant or salient, and the ways in which their goals relate to other phenomena such as school achievement (King and McInerney, 2016). For example, in cross-cultural studies of academic goals, Dekker and Fischer (2008) found that gaining social approval in achievement contexts was particularly important for students who had a collectivist perspective. This cultural value may predispose students to adopt goals that help them to avoid the appearance of incompetence or negative judgments (i.e., performance-avoidance goals) (Elliot, 1997, 1999; Kitayama, Matsumoto, and Norasakkunkit, 1997).

More recent work has also explored the relationships between such differences and cultural context. For example, several studies have compared students’ indications of endorsement for performance-avoidance goals and found that Asian students endorsed these goals to a greater degree than European American students did (Elliot et al., 2001; Zusho and Njoku, 2007; Zusho et al., 2005). This body of work seems to suggest that though there were differences, the performance avoidance may also have different outcomes in societies in which individualism is prioritized than in more collectivistic ones. These researchers found that performance-avoidance goals can be adaptive and associated with such positive academic outcomes as higher levels of engagement, deeper cognitive processing, and higher achievement. (See also the work of Chan and Lai [2006] on students in Hong Kong; Hulleman et al. [2010]; and the work of King [2015] on students in the Philippines.)

Although cultures may vary on average in their emphasis on individualism and collectivism, learners may think in either individualistic and collectivistic terms if primed to do so (Oyserman et al., 2009). For example, priming interventions such as those that encourage participants to call up personal memories of cross-cultural experiences (Tadmor et al., 2013) have been used successfully to shift students from their tendency to take one cultural perspective or the other. Work on such interventions is based on the assumption that one cultural perspective is not inherently better than the other: the most effective approaches would depend on what the person is trying to achieve in the moment and the context in which he is operating. Problem solving is facilitated when the salient mindset is well matched to the task at hand, suggesting that flexibility in cultural mindset also may promote flexible cognitive functioning and adaptability to circumstances (Vezzali et al., 2016).

This perspective also suggests the potential benefits of encouraging learners to think about problems and goals from different cultural perspectives. Some evidence suggests that these and other multicultural priming interventions improve creativity and persistence because they cue individuals to think of problems as having multiple possible solutions. For instance, priming learners to adopt a multicultural mindset may support more-divergent thinking about multiple possible goals related to achievement, family, identity, and

friendships and more flexible action plans for achieving those goals. Teachers may be able to structure learning opportunities that incorporate diverse perspectives related to cultural self-construals in order to engage students more effectively (Morris et al., 2015).

However, a consideration for both research and practice moving forward is that there may be much more variation within cultural models of the self than has been assumed. In a large study of students across several nations that examined seven different dimensions related to self-construal (Vignoles et al., 2016), researchers found neither a consistent contrast between Western and non-Western cultures nor one between collectivistic and individualistic cultures. To better explain cultural variation, the authors suggested an ecocultural perspective that takes into account racial/ethnic identity.

Social Identity and Motivation Processes

Identity is a person’s sense of who she is. It is the lens through which an individual makes sense of experiences and positions herself in the social world. Identity has both personal and social dimensions that play an important role in shaping an individual’s goals and motivation. The personal dimensions of identity tend to be traits (e.g., being athletic or smart) and values (e.g., being strongly committed to a set of religious or political beliefs). Social dimensions of identity are linked to social roles or characteristics that make one recognizable as a member of a group, such as being a woman or a Christian (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). They can operate separately (e.g., “an African American”) or in combination (“an African American male student”) (Oyserman, 2009).

Individuals tend to engage in activities that connect them to their social identities because doing so can support their sense of belonging and esteem and help them integrate into a social group. This integration often means taking on the particular knowledge, goals, and practices valued by that group (Nasir, 2002). The dimensions of identity are dynamic, malleable, and very sensitive to the situations in which people find themselves (Oyserman, 2009; Steele, 1997). This means the identity a person takes on at any moment is contingent on the circumstances

A number of studies indicate that a positive identification with one’s racial or ethnic identity supports a sense of school belonging, as well as greater interest, engagement, and success in academic pursuits. For example, African American adolescents with positive attitudes toward their racial/ethnic group express higher efficacy beliefs and report more interest and engagement in school (Chavous et al., 2003). The value of culturally connected racial/ethnic identity is also evident for Mexican and Chinese adolescents (Fuligni et al., 2005). In middle school, this culturally connected identity is linked to higher grade-point averages among African American (Altschul et al., 2006; Eccles et al., 2006), Latino (Oyserman, 2009), and Native American students in North

BOX 6-3 Basketball, Mathematics, and Identity

America (Fryberg et al., 2013). The research described in Box 6-3 illustrates the potential and powerful influence of social identity on learners’ engagement with a task.

Stereotype Threat

The experience of being evaluated in academic settings can heighten self-awareness, including awareness of the stereotypes linked to the social group to which one belongs and that are associated with one’s ability (Steele, 1997). The effects of social identity on motivation and performance may be positive, as illustrated in the previous section, but negative stereotypes can lead people to underperform on cognitive tasks (see Steele et al., 2002; Walton and Spencer, 2009). This phenomenon is known as stereotype threat, an unconscious worry that a stereotype about one’s social group could be applied to oneself or that one might do something to confirm the stereotype (Steele, 1997). Steele has noted that stereotype threat is most likely in areas of performance in which individuals are particularly motivated.

In a prototypical experiment to test stereotype threat, a difficult achievement test is given to individuals who belong to a group for whom a negative stereotype about ability in that achievement domain exists. For example, women are given a test in math. The test is portrayed as either gender-neutral

(women and men do equally well on it) or—in the threat condition—as one at which women do less well. In the threat condition, members of the stereotyped group perform at lower levels than they do in the gender-neutral condition. In the case of women and math, for instance, women perform more poorly on the math test than would be expected given their actual ability (as demonstrated in other contexts) (Steele and Aronson, 1995). Several studies have replicated this finding (Beilock et al., 2008; Dar-Nimrod and Heine, 2006; Good et al., 2008; Spencer et al., 1999), and the finding is considered to be robust, especially on high-stakes tests such as the SAT (Danaher and Crandall, 2008) and GRE.

The effects of negative stereotypes about African American and Latino students are among the most studied in this literature because these stereotypes have been persistent in the United States (Oyserman et al., 1995). Sensitivity to these learning-related stereotypes appears as early as second grade (Cvencek et al., 2011) and grows as children enter adolescence (McKown and Strambler, 2009). Among college-age African Americans, underperformance occurs in contexts in which students believe they are being academically evaluated (Steele and Aronson, 1995). African American school-age children perform worse on achievement tests when they are reminded of stereotypes associated with their social group (Schmader et al., 2008; Wasserberg, 2014). Similar negative effects of stereotype threat manifest among Latino youth (Aronson and Salinas, 1997; Gonzales et al., 2002; Schmader and Johns, 2003).

Stereotype threat is believed to undermine performance by lowering executive functioning and heightening anxiety and worry about what others will think if the individual fails, which robs the person of working memory resources. Thus, the negative effects of stereotype threat may not be as apparent on easy tasks but arise in the context of difficult and challenging tasks that require mental effort (Beilock et al., 2007).

Neurophysiological evidence supports this understanding of the mechanisms underlying stereotype threat. Under threatening conditions, individuals show lower levels of activation in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, reflecting impaired executive functioning and working memory (Beilock et al., 2007; Cadinu et al., 2005; Johns et al., 2008; Lyons and Beilock, 2012; Schmader and Jones, 2003) and higher levels of activation in fear circuits, including, for example, in the amygdala (Spencer et al., 1999; Steele and Aronson, 1995).

In the short term, stereotype threat can result in upset, distraction, anxiety, and other conditions that interfere with learning and performance (Pennington et al., 2016). Stereotype threat also may have long-term deleterious effects because it can lead people to conclude that they are not likely to be successful in a domain of performance (Aronson, 2004; Steele, 1997). It has been suggested that the longer-term effects of stereotype threat may be one cause of longstanding achievement gaps (Walton and Spencer, 2009). For example, women for whom the poor-at-math stereotype was primed reported

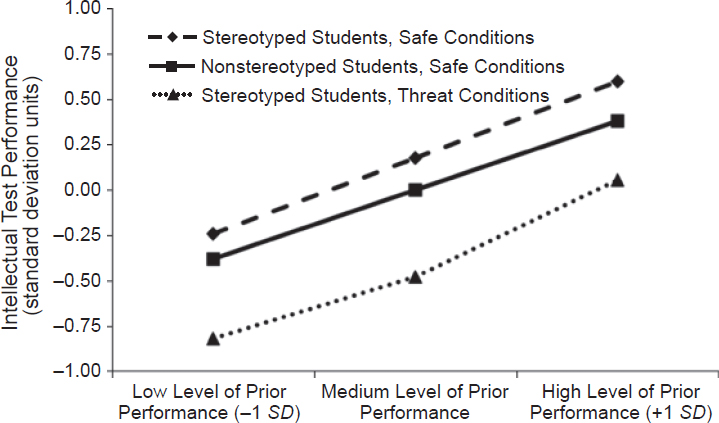

NOTE: SD refers to standard deviation.

SOURCE: Walton and Spencer (2009, Fig.1).

more negative thoughts about math (Cadinu et al., 2005). Such threats can be subtly induced. In one classroom study, cues in the form of gendered objects in the room led high school girls to report less interest in taking computer science courses (Master et al., 2015).

Students can maintain positive academic self-concepts in spite of negative stereotypes when supported in doing so (Anderman and Maehr, 1994; Graham, 1994; Yeager and Walton, 2011). For example, a study by Walton and Spencer (2009) illustrates that under conditions that reduce psychological threat, students for whom a stereotype about their social group exists perform better than nonstereotyped students at the same level of past performance (see Figure 6-1).

These findings highlight an important feature of stereotype threat: it is not a characteristic solely of a person or of a context but rather a condition that results from an interaction between the two. To be negatively affected, a person must be exposed to and perceive a potential cue in the environment and be aware of a stereotype about the social group with which he identifies (Aronson et al., 1999). For example, in a study of African American children in an urban elementary school, introduction of a reading test as an index of ability hampered performance only among students who reported being aware of racial stereotypes about intelligence (Walton and Spencer, 2009).

It also appears that the learner must tie her identity to the domain of skills

being tested. For example, students who have a strong academic identity and value academic achievement highly are more vulnerable to academic stereotype threat than are other students (Aronson et al., 1999; Keller, 2007; Lawrence et al., 2010; Leyens et al., 2000; Steele, 1997).

Researchers have identified several actions educators can take that may help to manage stereotype threat. One is to remove the social identity characteristic (e.g., race or gender) as an evaluating factor, thereby reducing the possibility of confirming a stereotype (Steele, 1997). This requires bolstering or repositioning dimensions of social identity. Interventions of this sort are likely to work not because they reduce the perception of, or eliminate, stereotype threat, but because they change students responses to the threatening situation (Aronson et al., 2001; Good et al., 2003). For example, learners can be repositioned as the bearers of knowledge or expertise, which can facilitate identity shifts that enable learners to open up to opportunities for learning (Lee, 2012). In research that confronted women with negative gender-based stereotypes about their performance in mathematics but prompted them to think of other aspects of their identity, the women performed on par with men and appeared to be buffered against the deleterious effects of gender-based stereotypes. Women who did not receive the encouragement performed worse than their male counterparts (Gresky et al., 2005). Such findings suggest that having opportunities to be reminded of the full range of dimensions of one’s identity may promote resilience against stereotype threats. Notably, interventions that have addressed stereotype threat tend to target and support identity rather than self-esteem. However, clear feedback that sets high expectations and assures a student that he can reach those expectations are also important (Cohen and Steele, 2002; Cohen et al., 1999).

Values-affirmation interventions are designed to reduce self-handicapping behavior and increase motivation to perform. Enabling threatened individuals to affirm their talents in other domains through self-affirmations has in some situations strengthened students’ sense of self (McQueen and Klein, 2006). Values-affirmation exercises in which students write about their personal values (e.g., art, sports, music) have bolstered personal identity, reduced threat, and improved academic performance among students experiencing threat (Cohen et al., 2006, 2009; Martens et al., 2006). In randomized field experiments, self-affirmation tasks were associated with better grades for middle school students (Cohen et al., 2006, 2009)4 and college students (Miyake et al., 2010). However, other studies have not replicated these findings (e.g., Dee, 2015; Hanselman et al., 2017), so research is needed to determine for whom and under which conditions values-affirmation approaches may be effective.

Although research suggests steps that educators can take that may help to

___________________

4 The 2006 study included 119 African American and 119 European American students; the 2009 study was a 2-year follow-up with the same sample.

eliminate stereotype threat, much of this research has been in highly controlled settings. The full range of factors that may be operating and interacting with one another has yet to be fully examined in real-world environments. However, educators can take into account the influences that research has identified as potentially causing, exacerbating, or ameliorating the effects of stereotype threat on their own students’ motivation, learning, and performance.

INTERVENTIONS TO IMPROVE MOTIVATION

Many students experience a decline in motivation from the primary grades through high school (Gallup, Inc., 2014; Jacobs et al., 2002; Lepper et al., 2005). Researchers are beginning to develop interventions motivated by theories of motivation to improve student motivation and learning.

Some interventions focus on the psychological mechanisms that affect students’ construal of the learning environment and the goals they develop to adapt to that environment. For example, a brief intervention was designed to enhance student motivation by helping learners to overcome the negative impact of stereotype threat on social belongingness and sense of self (Yeager et al., 2016). In a randomized controlled study, African American and European American college students were asked to write a speech that attributed adversity in learning to a common aspect of the college-adjustment process rather than to personal deficits or their ethnic group (Walton and Cohen, 2011). After 3 years, African American students who had participated in the intervention reported less uncertainty about belonging and showed greater improvement in their grade point averages compared to the European American students.

One group of interventions to address performance setbacks has focused on exercises to help students shift from a fixed view of intelligence to a growth theory of intelligence. For example, in 1-year-long study, middle school students attended an eight-session workshop in which they either learned about study skills alone (control condition) or both study skills and research on how the brain improves and grows by working on challenging tasks (the growth mindset condition). At the end of the year, students in the growth mindset condition had significantly improved their math grades compared to students who only learned about study skills. However, the effect size was small and limited to a small subset of underachieving students (Blackwell et al., 2007).

The subjective and personal nature of the learner’s experiences and the dynamic nature of the learning environment require that motivational interventions be flexible enough to take account of changes in the individual and in the learning environment. Over the past decade, a number of studies have suggested that interventions that enhance both short- and long-term motivation and achievement using brief interventions or exercises can be effective (e.g., Yeager and Walton, 2011). The interventions that have shown sustained effects on aspects of motivation and learning are based on relatively brief activities

and exercises that directly target how students interpret their experiences, particularly their challenges in school and during learning.

The effectiveness of brief interventions appears to stem from their impact on the individual’s construal of the situation and the motivational processes they set in motion, which in turn support longer-term achievement. Brief interventions to enhance motivation and achievement appear to share several important characteristics. First, the interventions directly target the psychological mechanisms that affect student motivation rather than academic content. Second, the interventions adopt a student-centric perspective that takes into account the student’s subjective experience in and out of school. Third, the brief interventions are designed to indirectly affect how students think or feel about school or about themselves in school through experience, rather than attempting to persuade them to change their thinking, which is likely to be interpreted as controlling. Fourth, these brief interventions focus on reducing barriers to student motivation rather than directly increasing student motivation. Such interventions appear particularly promising for African American students and other cultural groups who are subjected to negative stereotypes about learning and ability. However, as Yeager and Walton (2011) note, the effectiveness of these interventions appears to depend on both context and implementation.

Studies such as these are grounded in different theories of motivation related to the learners’ cognition, affect, or behavior and are intended to affect different aspects of motivation. Lazowski and Hulleman (2016) conducted a meta-analysis of research on such interventions to identify their effects on outcomes in education settings. The studies included using measures of authentic education outcomes (e.g., standardized test scores, persistence at a task, course choices, or engagement) and showed consistent, small effects across intervention type.

However, this meta-analysis was small: only 74 published and unpublished papers met criteria for inclusion, and the included studies involved a wide range of theoretical perspectives, learner populations, types of interventions, and measured outcomes. These results are not a sufficient basis for conclusions about practice, but further research may help identify which interventions work best for whom and under which conditions, as well as factors that affect implementation (such as dosage, frequency, and timing). Improvements in the ability to clearly define, distinguish among, and measure motivational constructs could improve the validity and usefulness of intervention research.

CONCLUSIONS

When learners want and expect to succeed, they are more likely to value learning, persist at challenging tasks, and perform well. A broad constellation of factors and circumstances may either trigger or undermine students’ desire

to learn and their decisions to expend effort on learning, whether in the moment or over time. These factors include learners’ beliefs and values, personal goals, and social and cultural context. Advances since the publication of HPL I provide robust evidence for the importance of both an individual’s goals in motivation related to learning and the active role of the learner in shaping these goals, based on how that learner conceives the learning context and the experiences that occur during learning. There is also strong evidence for the view that engagement and intrinsic motivation develop and change over time—these are not properties of the individual or the environment alone.

While empirical and theoretical work in this area continues to develop, recent research does strongly support the following conclusion:

CONCLUSION 6-1: Motivation to learn is influenced by the multiple goals that individuals construct for themselves as a result of their life and school experiences and the sociocultural context in which learning takes place. Motivation to learn is fostered for learners of all ages when they perceive the school or learning environment is a place where they “belong” and when the environment promotes their sense of agency and purpose.

More research is needed on instructional methods and how the structure of formal schooling can influence motivational processes. What is already known does support the following general guidance for educators:

CONCLUSION 6-2: Educators may support learners’ motivation by attending to their engagement, persistence, and performance by:

- helping them to set desired learning goals and appropriately challenging goals for performance;

- creating learning experiences that they value;

- supporting their sense of control and autonomy;

- developing their sense of competency by helping them to recognize, monitor, and strategize about their learning progress; and

- creating an emotionally supportive and nonthreatening learning environment where learners feel safe and valued.