2

Community-Driven Approaches to Building Healthy Communities

The workshop’s first panel session featured presentations on two community-level programs that are building healthy communities in California. Prior to the presentations, Anthony Iton, the senior vice president for Building Healthy Communities (BHC)1 at The California Endowment, provided his views on how the nation got to where it is with regard to health inequities and how The California Endowment is addressing these inequities. Andrea Manzo, a hub manager for BHC in East Salinas, California, and Kanwarpal Dhaliwal, the co-founder and community health director at RYSE2 in Richmond, California, then described programs that are translating theory into practice in two California communities. Following the presentations (highlights provided in Box 2-1), Iton moderated an open discussion among the workshop participants.

CONTEXT SETTING3

Launched by The California Endowment in 2010, the goal of BHC is to improve community health status by addressing determinants of health

___________________

1 For more information, go to http://www.calendow.org/building-healthy-communities (accessed March 21, 2017).

2 For more information, go to http://rysecenter.org (accessed February 5, 2018).

3 This section is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of the presentation made by Anthony Iton, the senior vice president for Building Healthy Communities at The California Endowment, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

rather than spending on health care. Iton described how the foundation is investing $1 billion in 14 low-income communities in California over the course of 10 years. BHC’s strategy involves capacity building, narrative change, partnerships, and policy advocacy to produce health equity and measurable results. While he and his colleagues at The California Endowment created the specifications of this program, people such as

Andrea Manzo and Kanwarpal Dhaliwal are responsible for translating these notions into practice.

Before turning the podium over to Manzo and Dhaliwal, Iton said he wanted to remind everyone how health disparities and inequities became so widespread in this country. “These communities did not arise spontaneously—they were created—and until we understand the forces and ideologies that created them, it is hard to undo them,” he said. As a way to help the participants understand his own perspective on the pernicious history and legacy of structural racism, Iton started by reading a quote by Abraham Lincoln in which he stated that he did not favor “bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races,” nor did he believe that blacks should have the right to vote or marry whites (The New York Times, 1860). Lincoln also claimed that there was “a physical difference between the white and black races” that forbade “living together on terms of social and political equality.” Instead, Lincoln believed that while the two races could not live together, there “must be the position of superior and inferior” and Lincoln was in favor of whites being assigned the superior position (The New York Times, 1860).

Iton went on to cite the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision in which the justices opined that in the language used in the Declaration of Independence, it was shown that “neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.” Again emphasizing the “inferiority” of blacks, the Court’s decision claimed that blacks were “unfit” to “associate with the white race, either in social or political relations and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit” (U.S. Supreme Court, 1859). Iton also quoted the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who during oral arguments in a case involving affirmative action at The University of Texas cited claims that some African Americans are harmed academically by attending elite universities such as The University of Texas, and that they may be better served by attending “lesser schools.”4

As a final example of the historical context for his work, Iton recited the third stanza of the Star Spangled Banner. It says in part that during the “havoc of war and the battle’s confusion” that “No refuge could save the hireling and slave from the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave: And

___________________

4 For more information, go to https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2015/12/10/read-the-most-controversial-statement-by-justice-scalia-on-admissions-and-race (accessed March 21, 2017).

the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave, o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave” (National Museum of American History, n.d.).

Iton explained that he shared the quotes not only to be a provocateur, but also to help people to think about the legacies that inform where the country is today. When he considered strategies to explain communities, he examined many socioecological frameworks and concluded they were not adequate at describing social factors and the drivers of inequity. While a framework may describe broad social, economic, cultural, health, and environmental conditions and policies at the school, national, state, and local levels, racism is often excluded from the list of relevant factors (IOM, 2011). “I think this is a problem when we talk about race and not racism,” Iton said. “I put it to you that you cannot do this work and you will not be taken seriously by your partners if you do not talk about racism, if you do not talk about classism, if you do not talk about sexism, and do not talk about strategies to develop a practice that is anti-racist.”

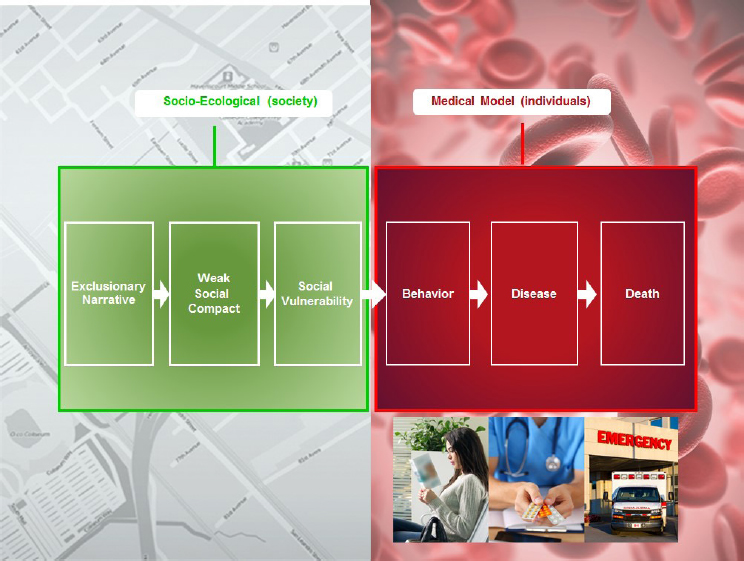

Out of this frustration, which Iton shared with other local health practitioners in the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative (BARHII), emerged the BARHII framework (see Figure 2-1). “This is a framework, not a model, and it does not try to explain how all of these things interact,” Iton said. “It just tries to pull apart the spectrum of opportunity for intervention and allow us to see where there may be meaningful opportunities to intervene.” The framework, he explained, recognizes that the traditional medical model talks about how individual behavior produces disease, which produces premature mortality, and that the medical model then offers health education, clinical care, and emergency departments to try to contend with these challenges.

Iton and his colleagues recognized that to get upstream, they had to determine where they could intervene in order to have an effect on health. These intervention points, he explained, are where social vulnerability manifests in a community—the places where groups of people are exposed to community-level risks, such as foreclosure, or HIV/AIDS, or a hurricane. “We have created social vulnerability in a group of people and situated them geographically in close proximity to one another,” he said.

From the perspective of Iton and his colleagues, a weak social compact and a set of policies and practices that do not anticipate inevitable human needs and that steer resources away from people categorized as less deserving of the full benefits of society are what create this situation. “We think that ultimately it is an exclusionary narrative, a way of thinking about who we are as Americans and who matters,” he said. An exclusionary narrative, Iton explained, depends on “targeting a population that is deemed to be unworthy and then dehumanizing that population.” An exclusionary narrative includes an argument that “we are in a zero sum competition, that there is scarcity, and if those others get what we need, we will suffer, so we need to be able to exclude them from fair competition

NOTE: For more information on this framework, go to http://www.calendow.org/building-healthy-communities (accessed on June 7, 2017).

SOURCE: Iton presentation, December 8, 2016.

for those resources.” The exclusionary narrative, he added, argues for a rosy, nostalgic past and a future full of fear and anxiety.

Overcoming the exclusionary narrative, Iton said, requires reweaving a social compact to create real social, political, and economic power—rather than social vulnerability—in a critical mass of people living in disadvantaged communities. That, in fact, is what BHC is trying to do by creating a powerful, inclusive narrative.

HEALING-INFORMED COMMUNITY POWER BUILDING5

Salinas, California, is a community of approximately 160,000, plus a large undocumented population, located in the heart of an $8 to $10 bil-

___________________

5 This section is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of the presentation made by Andrea Manzo, a hub manager for Building Healthy Communities in East Salinas, California, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

lion agricultural industry that supplies 70 percent of the nation’s lettuce, Manzo explained. She noted how the legacy of institutional and structural racism that Iton discussed has negatively affected communities of color such as Salinas. As Iton noted, structural racism did not come from nature. “It was not designed by people of color, nor does it reflect their experiences, their cultures, their languages,” Manzo said. Given that “power concedes nothing without a demand” (Douglass, 1857, p. 22), the only way to change such a system is to acquire the power necessary to have equal or greater power than those who designed that system and use that newfound power to change the system, Manzo said.

Manzo and her colleagues’ project, Healing Informed Governing for Racial Equity (Dieng et al., 2016), is a power-building and healing-informed approach grounded in a set of core shared values and principles, and it emphasizes capacity building in the struggle to dismantle structural racism in Salinas. These core shared values help ensure that the preservation of the values and the dignity of the people in the community is the paramount concern, not saving money or minimizing resources. This healing-informed approach, Manzo explained, is different in that it uses a relational rather than a transactional approach. “Often, we think with our minds but not with our hearts, and I think power is really in the connection of the two,” she said. Taking a relational approach creates an opportunity to acknowledge the historical trauma the community has experienced and to use that as a strength to transform the community.

One important piece of this work, Manzo said, is that it gives a name to the experiences the community’s residents have lived so that they can have a common language with which to talk to system leaders. Having a shared language enables community members to build relationships both with those in government who have power and among themselves. “We are building the power and capacity of residents to analyze the structural problems and helping them realize they have the right to push our system leaders to change their policies that are affecting all areas of our lives,” she said. The program includes multiple trainings on racial equity and historical traumas that allow community members to connect with one another, to build power and strength, and to exercise the emotional fortitude to deal with those traumas and move to action.

Another important programmatic emphasis has been to shift the narrative about Salinas away from one that stresses gang violence. Manzo said that Salinas has been labeled the nation’s youth murder capital on several occasions. Rather than focusing solely on gang violence as a problem, there is a need to focus the conversation on violence as a symptom of a broader problem to solve, she said. The conversation needs to focus on the strengths of the community, the resiliency of the hard-working people that live in Salinas, and on the value of the community’s youth

as assets and leaders rather than liabilities, Manzo said. Instead of solely blaming residents for negative health outcomes, there is a need to shift some responsibility to the local government, Manzo said. The government needs to do its part to invest in residents, while residents need to constantly organize and exert their collective power to ensure that the government meets its own responsibilities concerning issues that affect their well-being and their overall health, Manzo added.

Manzo recounted the first time she was bothered by the idea of centering the community’s problems around gang violence. “I had gone to a community meeting, a collaborative made up of service-based organizations, community-based organizations, and, most importantly, law enforcement and elected officials and staff. Their presentation was on their violence prevention strategy, and I was automatically turned off because there was an introductory slide with a big red circle that said, ‘The Problem: Gang Violence.’” Gang violence is a symptom of the lack of affordable housing, green spaces, educational and vocational opportunities, and good-paying jobs in a region with a multi-billion-dollar agricultural industry, not something that just appeared with no context, Manzo said.

Manzo’s response was to invite the presenter, who happened to work at the county health department, into the BHC world. The result was that this person has now become the individual who keeps her colleagues and peers accountable as far as taking a strength-based approach when talking about the community and who pushes them to look for solutions that address the root causes of these social problems that influence the community’s health. “That would not have happened,” Manzo said, “if I had not opened my arms” and invited the presenter to “hang out with us” and “hear what we say.”

The power of owning a strength-based narrative is that it moves the discussion beyond one of “us versus them” with regard to government. “We cannot do this alone,” Manzo said. “It requires collaboration that stretches across sectors and, more often than not, reaches out to entities that are not traditionally seen as allies or partners.” The turning point, she said, was after four fatal officer-involved shootings occurred in 2014. Through that tragedy, her program was able to get buy-in from local government—not just the police department—to change the relationship between government and the community. Her team hosted a Healing-Informed Governing for Racial Equity training with city staff and community leaders which allowed them to name the inequities in the community and build the capacity of systems leaders to change the way they look at problems and find solutions. “It allowed us an opportunity to create that trust and to hold each other accountable and to really strip each other [of] our titles and be vulnerable and see our true selves,” Manzo said. “System leaders often do not humanize residents, and they see them as numbers,

they see them as data, and it also allowed the opportunity for residents themselves to see that these folks that are making those decisions are also human.”

After achieving a shared language and a shared understanding of the complexities of structural racism in Salinas, Manzo and her team began looking at the system as a whole and building the capacity of system leaders through a community engagement spectrum that is about empowering residents, not just checking a box. Today, partners in this effort are working with the county health department and the local government to improve the built environment for the community’s youth. “This would not have happened had BHC not opened the door for this type of collaboration,” Manzo said. The same individual from the public health department with whom Manzo had connected approached the city’s department of public works to invest in bathrooms, water fountains, and lights for parks in the city’s neighborhoods with the most need instead of focusing resources on wealthier parts of the city. This, of course, took some organizing by BHC through their inside (health department)/outside (community organizing) strategy. “It has become less about who screams loudest and more about who could and should benefit more and who has been left out of the equation historically,” Manzo said.

To illustrate the BHC approach in Salinas, Manzo used the upstream story often used in public health of the man fishing who rescues one person after another who is drowning in a stream. Realizing he does not have the strength to keep rescuing people from the fast-moving water, he goes upstream and finds that people are falling in the river because the bridge needs repairing. Her community, she said, has evolved in its thinking to not only fix the bridge that leads to health inequities, but to look at who is building the bridge, how it is built, who has access to the bridge, and whether the bridge is actually saving people and improving health outcomes.

Concluding her presentation, Manzo asked the workshop participants to think about a policy- and systems-change approach using a racial equity lens. “We need healing to be embedded in our work” and connect our thinking to our hearts, Manzo said. “We need to explore creative ways to be transparent and inclusive in the decision-making process,” she added. Manzo emphasized the importance of continuing to talk about structural racism because a consistent focus and conversation reduces anxiety and can lead to an approach in which racial equity become systemic. “The goal is to liberate us from this legacy of racism and oppression” and to give people the opportunity to have a chance to be healthier, she said. “In order to do this, we need to continue organizing and building power to keep our systems accountable to combating structural racism.”

SOCIAL JUSTICE AND BUILDING YOUTH POWER6

Dhaliwal described Richmond, California, as a community of immense fortitude, beauty, and resilience. Simultaneously, she said, Richmond is also a community that is over-surveilled, under-resourced, and governed by leadership that is challenged to address the needs and priorities of young members of the community. Richmond is composed of diverse communities of color traumatized by violence—historical, structural, and chronic—yet with residents who continue to show up every day with love, hope, and rage. The RYSE Center7 is a youth-centered organization that works with young people ages 13 to approximately 21 years old. It runs some 30 to 40 programs related to community health, education, youth justice, media, arts, and culture. Above all, Dhaliwal said, RYSE is a safe space that was borne out of young people organizing to change the conditions of violence in their community, to get adults to do the work necessary “to be in service and be responsible to young people.” She noted that the young people who first had the idea for the center in 2000 knew it would take years to establish—the center opened in 2008—and that they would never directly benefit from the services and programs they envisioned the center offering. “They were thinking about legacy, and it is in this spirit that I honor and offer what I have to share,” she said.

Before describing RYSE, Dhaliwal asked the workshop participants to consider one idea: If the population health field continues to look at the issues of equity and social determinants of health from a white, middle-class, overeducated perspective, it will continue to be culpable for the inequities these communities face.

As a public health organization, RYSE is grounded in the ecological model of health, meaning that its members understand that “health is about where we live, who we are around, and what schools we go to,” Dhaliwal said. Even in their direct services, RYSE staff focus their efforts “on changing systems, changing culture, and changing the narrative,” so when therapists, case managers, or studio managers are engaging with young people, their relationships are based on the validation of the young people’s experiences, “the fortitude of these young people, and the harm that systems are causing,” Dhaliwal said. RYSE is a trauma-informed organization that seeks to make it easier for young people to come through the doors by meeting them where they are. “We do not ask

___________________

6 This section is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of the presentation by Kanwarpal Dhaliwal, co-founder and community health director at RYSE in Richmond, California, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

7 For more information, go to http://rysecenter.org (accessed February 5, 2018).

what is wrong with you or even what happened to you,” she said. “We appreciate that you are here and that you trust us enough to be here.”

The dominant media narrative of Richmond, Dhaliwal said, is that the young people are violent and harmful to one another. RYSE is working to change that narrative and challenge the systems that create and perpetuate it and also to talk about violence as a symptom of the level of the dehumanization and subjugation in which the residents live, Dhaliwal said. RYSE is grounded in addressing the social determinants of health. Staff members approach their work with an understanding of the relationships and structural conditions that have led to disease in the community by shifting the focus to producing instead a community of health, healing, justice, equity, and liberation, Dhaliwal said. If equity and optimal health are based on a model that presumes that people have racial and class power and privilege, it may do harm. Dhaliwal said that her perspective is grounded in lived experience and the process of understanding the structural forces at work in the community.

Dhaliwal shared an illustrative story about a hospital-linked violence intervention program run under a contract with the regional trauma center, which is located 24 miles from Richmond in an affluent white community. When a young person is shot, stabbed, or assaulted, he or she is transported to the trauma center, where the police immediately begin questioning that individual, often while he or she is still in shock. Many, if not most, of the victims are later denied victim-of-crime compensation services, to which they are rightfully entitled, because the police reports state they are noncompliant and do not acknowledge the trauma they just suffered. Dhaliwal’s program’s work is to share such lived experiences as examples of how systems perpetrate harm. “So while we understand behavior and outcomes and individual health indicators are important,” she said, “our focus is on changing the systems and conditions because if we solely focus on behaviors and only behaviors, we continue to replicate the systems of oppression, inequity, and dehumanization.” By grounding their work in intersectionality and an understanding that there are multiple, intersecting movements for liberation, RYSE operates as an anti-oppression organization that promotes racial, queer, and gender justice. The end goal, she said, is liberation.

Dhaliwal said that her program received strong support from The California Endowment even before the BHC initiative started. Nonetheless, RYSE engages in what Dhaliwal characterized as “healthy struggles” with its partners and stakeholders. “We have to be bigger and bolder than our logic models, than our theories of change,” by striving for liberation, she said. If we define success only as meeting our grant deliverables, she said, we are culpable of continued harm.

However, RYSE is a learning organization that has used data to guide

its decision making and planning. Dhaliwal credits the young people in the community with driving the organization to think about data and learning in a different way. As a result, the organization’s members are looking at the idea of developing a syndemics framework of research and data to enable them to conflate factors in a way that would help them understand the synergy and relationship among those social factors instead of doing regression analysis.

In closing, Dhaliwal suggested that workshop participants visit the RYSE website8 and watch some of the videos that illustrate what the young people in the Richmond community are doing to address the social determinants of health and create a system of racial justice and anti-oppression. “I do my best to speak truth to the power of young people, but I also know that there is just nothing that can replace [their own stories],” she said. “So I would really ask that you take a look at the work the young people have done, because that is really where the stories are and where the opportunity for transformation is.”

DISCUSSION

Iton began the discussion by asking the panelists to list the critical resources they need from academia, philanthropy, health care organizations, advocacy organizations, and other potential partners to do the kind of work they see as most important in their communities. Dhaliwal answered with a story of a partnership that RYSE has with the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley. After 5 years of serving as first responders for multiple kinds of violence and trauma affecting young people in Richmond, she and her colleagues went to the city government for help dealing with this issue but were told that they needed data to support their claims. RYSE partnered with the School of Public Health to design a data collection program, called the Listening Campaign, that allowed more than 500 young people in Richmond to share their experiences of violence, trauma, coping, and healing in way that was rigorous and allowed for the sort of data analysis that would influence city officials. As partners, the School of Public Health did not send privileged graduate students into Richmond to interview the young people of color in Richmond but rather helped her program with coding and establishing the rigorous analytic process. Dhaliwal stressed that this partnership was not built on money—her program did not have funds to support this effort—but rather on the relationships that her staff formed with researchers and students in the School of Public Health. The key to success in this relationship, Dhaliwal said, was that the teams from the

___________________

8 For more information, go to http://rysecenter.org (accessed February 5, 2018).

two partners were willing and able to step into a partnership grounded in “trust and healthy struggle.”

Manzo agreed that partnerships are not always about financial resources. She added, however, that financial resources do play an important role by enabling capacity building. “Many organizations in East Salinas are emerging organizations, organizations that did not exist before BHC,” she said, “but we have seen tremendous wins with these folks in these organizations because they are grounded in lived experience.” The key here, Manzo added, is having the resources to invest in and take a chance with those who have lived experiences and have good ideas on how to address the problems that affect their communities. Part of that capacity building, she added, is helping these nascent organizations understand what they need to do in order to secure additional funding once the initial pot of money is gone.

Gloria Escobar, the founder of a new initiative called the Coaction Institute, asked about the sustainability of resources, particularly of the people involved in these programs. The California Endowment, she said, is a unique external partner in that it understands the need for long-term external investments in these types of programs, but even those investments are designed to end after 10 years. Given that, she asked the panelists how their programs were getting local investors to build on what BHC has started. Manzo said that her organization in East Salinas has taken the approach of demonstrating the value of their programs and showing the local health department, for example, that the organization is irreplaceable. So far, BHC has received small amounts of funding from the health department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to demonstrate the value of its work. BHC has also secured a grant from the City of Salinas to do community engagement. Manzo said that it is important to be intentional about applying for grants from sources that can understand and appreciate the value of the work these programs do in the community. She added that The California Endowment program manager for the BHC hub is having conversations with local funders to convince them that if their goal is to achieve true community transformation, they need to invest in programs that have lasting value as opposed to those that merely put band-aids on local problems.

Judi Nightingale from the 1-year-old Riverside County Population Health Department asked how she as a white, middle-class, privileged individual could contribute to building a better community for the disenfranchised, largely Hispanic population in her county. She asked the panelists for their ideas on whom she should consider as outreach partners. Dhaliwal responded that she appreciated Nightingale’s understanding of what her position might be with respect to her community. What is important in finding partners, she said, is having the ability to see what

a healthy struggle looks like, to be able to see each other’s humanity, and to understand that the work that needs to be done will not be at each other’s expense. She admitted that having that attitude can be hard, and she said that success will come from dealing with the uncomfortable and sometimes angry emotions that will arise at times and remaining committed to the struggle and getting through those moments. It is important for white people in this work to develop their capacity for discomfort, hold each other accountable, and “develop a thick skin.” At the same time, it is important for people of color and structurally vulnerable communities to commit to and contend with prioritizing their humanity and not accommodating white privilege/fragility at their own expense.

Phyllis Meadows of The Kresge Foundation asked the panelists if there has been an opportunity for the 14 BHC communities to come together strategically on some health issue that could be addressed at the state level in addition to the local level. Iton said that the 14 communities funded by BHC are working on local issues in an environmental change framework with three primary components: schools, neighborhoods, and prevention or human services systems such as criminal justice, health care, and social services. That framework, he said, is consistent across the 14 communities, and it feeds into the part of the BHC program that he did not discuss, which is a statewide and regional policy change infrastructure that intersects with what is happening on the ground in these communities. “There is a bidirectional flow of learning, knowledge, and then implementation of statewide policy,” he said.

Dhaliwal expanded on Iton’s remarks by explaining how the Listening Campaign’s approach was not to take the challenges identified from speaking with young people about their experiences and then tell them what behaviors they needed to change. “We were really committed to that [approach],” she said. Instead, she and her colleagues took the data and findings as they were getting them and held discussions about what these data and findings meant with stakeholders, community benefit organizations that are part of the Healthy Richmond Community, and public systems. For example, the main coping mechanism for young people was to smoke marijuana, and if her organization, which she said is the only harm reduction agency in Richmond, took a behavioral intervention approach, it would have started funding marijuana cessation classes. The responsibility of her program, however, is to meet young people where they are, and if that means they show up having smoked marijuana, then her program supports and works with them from that place. At the same time, the program pushes the local systems to lift zero-tolerance and abstinence-only clauses from their contracts and make funding contingent on using harm-reduction approaches. It then also creates spaces for mutual support and accountability among the community of providers to

make the necessary shifts in approach and practice. “This is an example of using data to lift conditions, and change structures and systems,” Dhaliwal said. This is public health, she added.

David Kindig from the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute asked Manzo if she could describe the leaders in her community and if any of those leaders come from the wealthy agricultural business sector in the Salinas area. Manzo replied that her program has yet to get representatives of the agricultural sector involved, calling that a long-term goal. Currently, system leaders come mostly from city and county government, with some involvement of local health care institutions, including the public hospital. She explained that she has not worked as much with service-based providers.

Marthe Gold from The New York Academy of Medicine asked the panelists if they had started thinking about how they were going to hold governments accountable, given that the signals from the most recent election cycle suggests that local governments may be spending less money on these types of programs. This is the best time to push local government to act in the best interest of local communities, Manzo said. She added that she believes that there is money for these programs, though perhaps from nontraditional sources such as health care and prisons, and she said that she has begun having conversations with local officials, categorizing them as amicable but slightly contentious. What is enabling these conversations, she added, is the set of core values that they all share, such as the importance of meeting the needs of the community and of valuing the dignity of the individuals in that community. These discussions, she said, are about holding local governments accountable to those core shared values.

Dhaliwal agreed this is the right time to push local governments and said that her young staff members do not feel much different after the recent federal election in that they were experiencing danger and distress before the election and will probably continue to have a similar experience. RYSE’s response to the election has been to figure out how to shore up the power, capacity, and fortitude the organization has built to deal with what might lie ahead. This includes making space for staff and stakeholders to reflect, share, listen, and learn how and to what degree communities will be affected and how they can continue to show up for and support each other. She added that the public systems in Richmond are rising to the occasion and realizing the importance of sustaining the progress the community has made. The key, she said, will be figuring out how to make sure the community’s lived experiences are visible and prioritized.

Iton said he is concerned about the future, but is working with local communities to strike a balance with regard to funding. For example, when he met with the Salinas city manager, he learned that 70 percent of

the city’s budget went to the police and fire departments. At the county level, he learned, a disproportionate amount of resources go to incarceration. BHC’s response has been to start a campaign, Our School is Not a Prison, that aims to shift the narrative about the investments the city and county are making in young people away from these punitive, downstream systems. That said, he acknowledged that it is frightening that California could lose $20 billion per year just from the Affordable Care Act—money that enabled the state to expand Medicaid services. Nonetheless, this prospect does not change the approach The California Endowment is taking to address these problems, which is to build power in the state’s underserved communities.

As an example, Iton mentioned that there has been success in getting the California justice system to make one million people eligible for having felony convictions reclassified into misdemeanors, which means that those individuals would no longer have to check a felony conviction box when applying for a job or housing. The state now has 250,000 undocumented children who are getting the full scope of Medicaid services because of the advocacy that humanized this population. Thanks to some policy changes, there are now 300,000 fewer school suspensions in communities such as Richmond and Salinas, a 40 percent drop in 3 years, Iton said. “There are profound changes that are happening here as a result of the work that is happening in these communities and how these communities are networking their power to change state policy,” he said.

Concluding the discussion, Iton predicted that there is going to be a clash between the direction California is moving and the direction the federal government seems set to move. He added that he and his colleagues see this as a good opportunity for organizing communities—an opportunity that is bringing people together across discipline and geography around a common set of aims. “We are afraid,” he said, “but we are doubling down on our strategy.”

This page intentionally left blank.