3

Improving Health Through Equitable Transformative Community Change

The workshop’s second panel featured two examples of what it looks like to create conditions that shift power to residents and improve the health and well-being of communities. Jennifer Lacson Varano, the manager of community benefit and emergency management at Dignity Health Saint Francis Memorial Hospital, and Will Douglas, the manager of community impact for the Saint Francis Memorial Hospital Foundation, described the work of the Tenderloin Health Improvement Partnership (TLHIP).1 Teal VanLanen, a community activator for the Algoma School District, and Pete Knox, the executive vice president and chief innovation and learning officer at Bellin Health, then spoke about the Live Algoma2 project in northeastern Wisconsin. Following the presentations (highlights provided in Box 3-1), Soma Stout, the executive lead of the 100 Million Healthier Lives3 program at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, moderated an open discussion.

100 MILLION HEALTHIER LIVES

Before introducing the panelists, Stout noted that the speakers represent two of the 24 Spreading Community Adopters through Learning and

___________________

1 For more information, go to http://www.saintfrancisfoundation.org/tenderloinhip (accessed March 31, 2017).

2 For more information, go to http://livealgoma.org (accessed March 31, 2017).

3 For more information, go to http://www.100mlives.org (accessed March 31, 2017).

Evaluation (SCALE)4 communities that, along with many other partners are involved in the 100 Million Healthier Lives initiative.5 Together these participants are learning to create a community of solutions by shifting the balance of power and equity. “We call 100 Million Healthier Lives an unprecedented collaboration of change agents who are pursuing an unprecedented result of 100 million people living healthier lives by 2020,” Stout said. “The way we are going to do that is not to go out and change them, it is actually by changing us, by transforming the way we think and act as people who are in communities and in systems of power, to transform the way we think and act to create health, well-being, and equity.”

Getting to that place, Stout said, will require unprecedented collaboration, the courage to ask questions about what is happening in a community, the courage to “fail forward,”6 and understanding that in coming together communities might create solutions and intentionally transform the systems that are creating inequity. Achieving this goal will require data and science, she said. It will also require understanding how to combine the stories of people with lived experiences and their insights about how the system works with the capacities of those who have more formal positions of power in these communities. Critical to this effort will be getting two groups to see each other not as separate but as part of the same team and to understand that each other’s piece of the puzzle is needed to create solutions that will benefit the health of everyone in their community.

The price of admission to 100 Million Healthier Lives and SCALE is equity,7 Stout said, and this program is asking what it looks like for a community to change in a way that enables everyone to thrive. Changing the way communities think, she said, requires everyone to develop their capacity to “lead from within.” “This means learning how to be self-reflective about who we are, where we are, and how we are leading so that we can develop the skills to understand our story and understand the story of the people that are before us and the places that are

___________________

4 For more information, go to http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-andnews/2015/04/communities-receive-funding-to-accelerate-and-deepen-efforts-to-improve-residents-health.html (accessed March 31, 2017).

5 This section is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of the introductory comments made by Soma Stout, executive lead of 100 Million Healthier Lives, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

6 To “fail forward” means to turn failures into opportunities to learn and do better in the future.

7 For more information on 100 Million Healthier Lives’ treatment of equity as the price of admission, go to http://www.100mlives.org/approach-priorities/#equity (accessed May 25, 2017).

before us,” she said. It also requires understanding what it looks like to come together and lead together, as well as to understand and appreciate where the differences among one another make an individual stronger and where they are mere relics of the past that need to be left behind, she said. It also means having the courage to work toward outcomes without knowing ahead of time what the paths to those outcomes will be, adopting a humble spirit of learning and improving together.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is funding this program, and Stout explained that rather than stating a desired outcome, the foundation is allowing these 24 communities to co-design the approaches needed to help accelerate themselves toward a culture of health. Stout said that as she and her colleagues have been figuring out what it looks like to create these communities of solution,8 they have been discovering a number of important elements that need considering: that people relate to each other in these communities in different ways; that the way leaders come together to create abundance is different in each community; and that the way a community takes on the change process to grow equity differs. Respecting and valuing these differences, Stout said in conclusion, translates to ownership that enables everybody in the community to thrive, particularly those who are most affected by the structural racism and inequities of their local systems.

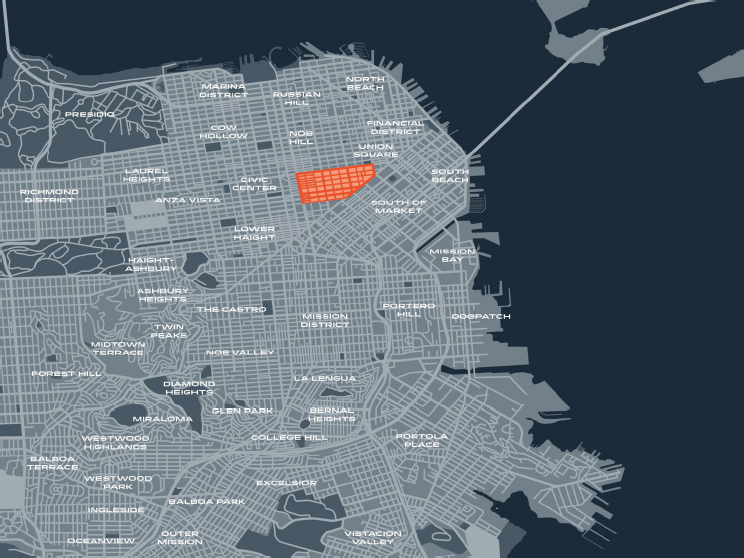

TENDERLOIN HEALTH IMPROVEMENT PARTNERSHIP9

TLHIP is a place-based initiative rooted in a collective impact model, Varano said. The Tenderloin neighborhood covers approximately 40 square blocks in the heart of downtown San Francisco (see Figure 3-1) and has a long history of complex issues similar to those seen in other urban centers, she added. It is an ethnically diverse neighborhood with more than 30,000 residents, including 3,000 children. The neighborhood’s median income is $27,269, compared with a citywide median of $84,160, and an estimated 57 percent of San Francisco’s homeless population lives in the Tenderloin. Access to open space in the neighborhood is low, and alcohol outlet density is over six times higher than in the city overall. The

___________________

8 For more readings on communities of solution, see the resource list posted on the roundtable’s activity page at http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/PublicHealth/PopulationHealthImprovementRT/16-DEC-08/Resource%20list%2012%205%202016.pdf (accessed January 29, 2018).

9 This section is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of the presentation by Jennifer Lacson Varano, the manager of community benefit and emergency management at Dignity Health Saint Francis Memorial Hospital, and Will Douglas, the manager of community impact for the Saint Francis Memorial Hospital Foundation, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

SOURCE: Douglas and Varano presentation, December 8, 2016.

Tenderloin ranks second in the city for preventable emergency department visits, with a rate more than twice that compared to the rest of the city. At the same time, there are more than 100 nonprofit agencies serving the neighborhood, offering health, housing, arts, youth, senior, and other social services.

Located just north of the Tenderloin, Saint Francis Memorial Hospital is a mission-driven, nonprofit organization that has served the Tenderloin and San Francisco for more than 100 years. “We have one of the busiest emergency departments, and we have invested a lot of time and money in our Charity Care program, as well as in building and strengthening relationships in the community to inform and design our Community Benefit program,” Varano said.

As TLHIP was starting its work, the San Francisco Health Improvement Partnership was spearheading an alignment effort among the many different community health assessments that the public health department, other private hospitals, and other individual organizations were conducting. She noted that at the same time, FSG, a mission-driven con-

sulting firm for leaders in search of large-scale, lasting social change, published its first paper on collective impact (Kania and Kramer, 2011). In addition, city residents were pressuring government to “do something” about the Tenderloin in response to an uptick in residential development, rapidly changing demographics, and a growing concern from the community about gentrification. Building on these events and our long history in the neighborhood, our hospital formed the TLHIP with the help and support of the Saint Francis Foundation, and convened a series of solutions-oriented dialogues with nonprofit executive leadership, city partners, private partners in philanthropy, as well as residents working in the Tenderloin, Varano said. “We acknowledged upfront that the impact of our collective efforts would take time and money and that failing forward quickly was okay. Our hospital and our foundation were prepared to provide that space to have those conversations and to bring others to the table where it could help.”

Adapting the citywide health needs assessment to the unique nature of the Tenderloin and looking specifically at safety issues, community connections, and opportunities for healthy choices, TLHIP was launched in 2014 as the first neighborhood-based coalition to pilot the vision and values expressed in the San Francisco Health Improvement Partnership, Varano said. While a focus on safety served as the entry point, over the past 3 years, “positively disrupting” organizational silos has been and continues to be TLHIP’s mantra. “We continue to learn how to do this with our community by co-creating with residents, using the framework of collective impact, convening stakeholders and residents to build consensus around issues and identify new ones, as well as solutions that resonate with the residents that are on the ground,” Varano said. Participating in the 100 Million Healthier Lives initiative, she said, has helped the program learn how to integrate improvement science10 and the “Plan, Do, Study, Act” cycle into its everyday work to continue to stay focused and continuously adapt.

Given the density of the issues and assets the program and its community partners initially identified, Varano said, it quickly became clear that the 40 square blocks in the Tenderloin were too big to target as a whole. Varano and her colleagues thus looked at the data and the deficits and created four action zones. For each action zone, the community residents helped to identify “game changers,” or key place-based interven-

___________________

10 IHI’s definition of improvement science is available at http://www.ihi.org/about/Pages/ScienceofImprovement.aspx (accessed May 25, 2017).

tions with the potential to enhance existing bright spots11 in the neighborhood or create new ones where they did not yet exist.

The first of these game changers, Varano said, were two projects—Boeddeker Park and Tenderloin Safe Passage—and a place-based strategy that was integrated into the city’s Tenderloin Central Market Strategy through the Mayor’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development. She said that one result of this alignment has been that researchers from the planning department were deployed in the neighborhood, fostering what she characterized as “a great working relationship” between the people in the neighborhoods and the city agencies “that has helped to improve both trust and communications to and from the community and City Hall.”

Douglas explained that this place-based strategy hinged on switching the narrative from one focusing on issues and needs to one that looked for bright spots and positive spaces in the community where the program could be nurtured. Boeddeker Park was just such a place, a space that historically had been one of the most dangerous areas in the neighborhood but that was also the largest open space in the neighborhood. TLHIP funded the local Boys & Girls Club to serve as the master tenant of Boeddeker Park and helped establish a partnership among the Boys & Girls Club, YMCA, San Francisco Police Department, and Tenderloin Safe Passage, another program that TLHIP helped create and fund. Today, Douglas said, Boeddeker Park is considered one of the brightest, safest, and most active spaces in the Tenderloin neighborhood. Over the past 2 years, Boeddeker Park has served 70,000 visitors and provided 3,400 hours of activities for the community.

Tenderloin Safe Passage works with community members to establish safe corridors for children and seniors that allow them to walk safely in the Tenderloin neighborhood. With a sustained investment over the past 2 years, Tenderloin Safe Passage has become a safety project adopted by the Tenderloin Community Benefit District that stations 20 corner captains, the majority of whom are residents of the community, for 1.5 hours daily on 7 of the highest-need corners, creating a safe corridor for an average of 650 schoolchildren per week.

Starting with Boeddeker Park and Tenderloin Safe Passage, TLHIP has been able to bring a variety of community organizations to the table, and the neighborhood is starting to see more positive changes occurring,

___________________

11 For more on bright spots, see http://www.100mlives.org/approach-priorities/opioid-resources/?sw=%5C%22bright+spots%5C%22 (accessed May 1, 2017) and for the resource list posted on the roundtable’s activity page, see http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/PublicHealth/PopulationHealthImprovementRT/16-DEC-08/Resource%20list%2012%205%202016.pdf (accessed January 29, 2018).

Douglas said. As the community partners continue to work and learn together, they are seeing that grants can be a helpful mechanism for seeding and activating collaboration in the community space. In 2 years, he said, TLHIP has given out 65 different grants to 41 organizations totaling nearly $2 million, seeding activities such as Four-Corner Friday, a monthly activity for the community, and Boeddeker Trekkers, a walking group that brings residents living in single-room occupancy hotels in to Boeddeker Park so that they can get 45 minutes of walking exercise, engage in community building, and get a healthy lunch. With the help of its many partners in the community, TLHIP closed a liquor store and established 826 Valencia,12 a nonprofit organization that supports students with their creative and expository writing skills. TLHIP also provided a grant to local artists to create a mural in Boeddeker Park to make it an even more appealing place for community activities.

Working together, the backbone team of TLHIP—i.e., the Saint Francis Foundation, Saint Francis Memorial Hospital Community Benefit, and a multisector community advisory committee—defined a common agenda that enables those organizations that serve the community daily through direct service to focus on strategic areas of need. “We can help them think more strategically across the entire neighborhood so that we can all work together and align our efforts better,” Douglas said. The backbone team also provides assistance with data collection, evaluation, consultations, and communicating and celebrating successes in the neighborhood. TLHIP has hosted and supported difficult conversations about community safety, community improvements, and intravenous drug use, even bringing intravenous drug users to a small stakeholder session to talk about their experiences in the community. “Bringing in residents, people with lived experiences, is the only way to identify solutions that are going to work for everyone,” Douglas said. In September 2016, city officials asked TLHIP to convene a meeting for its health commissioners to help them learn what was happening in the community.

Going forward, Douglas said, the future of the Tenderloin neighborhood looks brighter than it ever has. San Francisco has allocated funding for two additional neighborhood parks, and TLHIP is now driving a strategy of thinking about these parks as part of a network of safe places connected using Tenderloin Safe Passage. He said he believes that the success of Tenderloin Safe Passage and Boeddeker Park is leading residents to believe that these could be game changers for the community.

As TLHIP has been doing this work, Douglas, Varano, and their colleagues have been evolving the program’s framework which initially focused on broad-based safety and creating opportunities for making

___________________

12 For more information, go to http://826valencia.org (accessed March 31, 2017).

healthy choices. Today, TLHIP’s framework includes six areas—community engagement and neighborhood voice; active, vibrant, safe, and clean shared spaces; behavioral health; resident health; economic opportunity and affordable retail shopping; and housing access—that together are expected to reduce chronic disease and improve health outcomes for the residents of the Tenderloin. Through community-wide grants, positive community activation, and mutually reinforcing activities, we can see some clear outcomes and a quick return on those investments, but we are also trying to seed new ideas and things that take time to cultivate, Douglas said.

Douglas said that being part of the 100 Million Health Lives program and its SCALE program has taught him and his colleagues at TLHIP how to create authentic community by leading from within, leading together, and leading for outcomes. “For me,” he said, “what that means is every time I bring myself to a meeting with a community, I am just going to bring who I am and recognize that and respect people’s ability to do the same thing, and not just be who I am in work but who I am as a human.” Leading together, he added, means acknowledging that none of these activities work alone and that being a funder and a backbone organization13 is just supporting what is already taking place. To him, leading for outcomes involves looking at where TLHIP can use data and measurement in a manner that enables it to share results more widely. It also means acknowledging that this work will take time and that the benefits will accrue over the long term.

In closing, Douglas mentioned the 100 Million Healthier Lives Touchstones for Collaboration (see Box 3-2), a set of guiding principles that every member of the coalition has agreed to follow. The challenge as a backbone and provider, he said, is to “effectively integrate a resident voice and bring that into the work that we do. For me, the answer is not to tell the story of the community but actually let the community tell its own story.”

LIVE ALGOMA14

Algoma, Wisconsin, is not a racially diverse community—95 percent of its residents are white—but 55 percent of its students live in poverty and 25 percent of the community’s students have a cognitive or physical

___________________

13 For more information on backbone organizations, go to http://www.collaborationforimpact.com/collective-impact/the-backbone-organisation (accessed May 25, 2017).

14 This section is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of the presentation by Teal VanLanen, a community activator for the Algoma School District, and Pete Knox, the executive vice president and chief innovation and learning officer at Bellin Health, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

disability, VanLanen said. Her lived experience as a former fifth-grade teacher is that these demographics have created a great many obstacles in the classroom and that while there were many bright spots of individuals and organizations trying to address the community’s problems, they were doing their work in silos and not coming together as a community.

Knox said that efforts to transform systems fail 70 percent of the time, and that much of his work over the past 30 years has been aimed at understanding why failure occurs so often when trying to execute trans-formative strategies. He has developed a nationally recognized framework for building community that he and his colleagues at Bellin Health have applied to inner-city schools and elsewhere and that serves as the basis of the Live Algoma program.15 Knox’s goal is to use this framework to build a common language to tell stories about building communities wherever that happens.

___________________

15 For more information, go to http://livealgoma.org (accessed May 25, 2017).

Knox has identified five “domains of transformation” that are important to understand and incorporate in thinking about building community and that he believes are universal: (1) understand the system, (2) social change, (3) critical conversations, (4) co-creation, and (5) spread and scale. The process of radically transforming the community starts with understanding it as a system of interdependent and dynamic parts, the building blocks that make up community, that differ in every community. Next is building sustainable communities through social change, and having the critical conversations that further social change. Having critical conversations, Knox said, requires being vulnerable and inviting people in for conversation. “I am finding that around the world, people are desperate to have a conversation. They are waiting for the invitation, and that is up to us, but these are critical conversations. They are tough conversations.” Co-creating involves creating a safe space for people to come have these conversations in order to co-create, develop, build, and innovate together. Knox said that the Tenderloin team created such a space as part of its effort. Finally, Knox said, it is important to understand the concept of spread and scale; failure to do so limits how far solutions will go and also limits their sustainability.

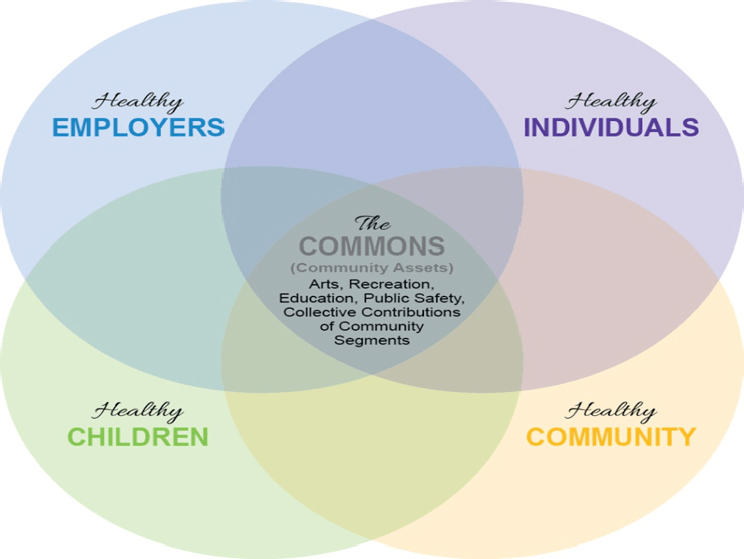

Using Live Algoma as an exemplar of these domains, Knox then went into more detail of how they are applied in practice. In terms of the first domain, his team’s understanding of Algoma as a community system was that it has five important interdependent parts (see Figure 3-2), the first of which is its children. “We needed to invite children in to be part of solving some of the big problems we have,” Knox said. Healthy employers were the second dimension because there needed to be a strong economic base in Algoma if this effort was to be successful. “We needed Algoma to be a place where employers wanted to move their businesses and build that economic base,” Knox said. As part of the effort to entice businesses to move to Algoma, Bellin Health created a new community collaborative insurance product in which one-third of any shared savings accruing from this product will go to support and sustain community work. Creating this new type of insurance represents an attempt to provide a long-term source of dollars to support community building that improves health and well-being.

The Algoma community’s third component is the health of its individuals. “We needed to engage every individual in the importance of their own health and well-being,” Knox said. A healthy community is the fourth part, and it requires the community to face the big social issues that exist in Algoma. The fifth component, at the intersection of the other four, is the commons, which are the assets of a community. The community needs to understand these assets, protect them, nurture them, and build them together, Knox said. People cannot just draw from

SOURCE: VanLanen and Knox presentation, December 8, 2016.

the commons; they have to be willing to contribute to the commons. Knox noted that in this conceptualization, a community is not hierarchical, but a living organism made of connected and interdependent parts engaged in a dynamic and responsive interchange between groups and levels.

VanLanen said that everybody in the community can find a place for himself or herself in this model of community and reiterated Knox’s statement that everyone can take from the commons, but they also have to contribute to it. “We educate our community members about the commons all of the time,” she said. She also pointed out that the programs growing out of this model are composed of community members. “For example,” she said, “in the healthy children team, we have someone from law enforcement, someone from social work, a private school teacher, a public school principal, a Hispanic mother, and two youths at the table.” The team is made up of a variety of people, each with a different perspective, who can talk about what it is in the Algoma community that creates a healthy child. Having those perspectives at the same table can lead to an authentic shared vision, VanLanen said. Knox added that every dimen-

sion has an activation team such as the one VanLanen described for the healthy children domain.

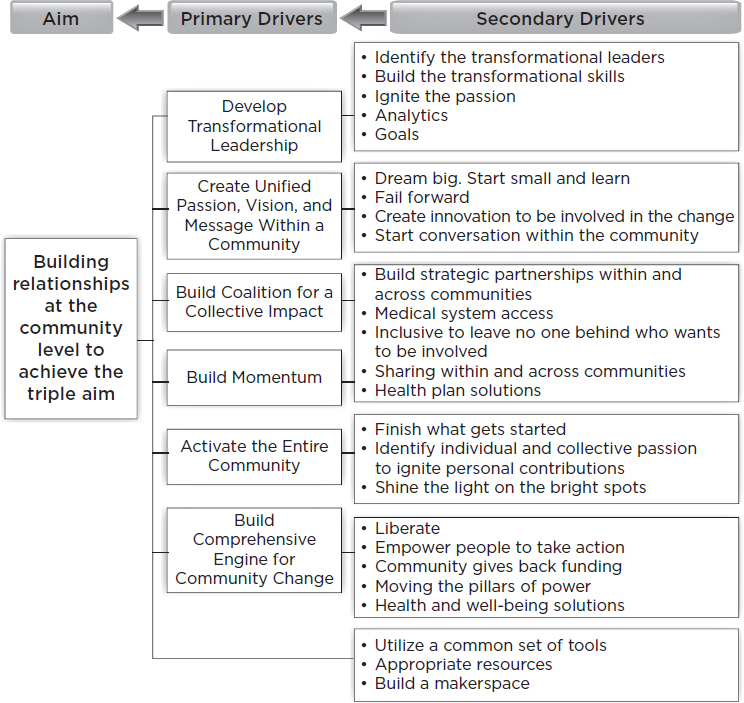

With regard to the second domain, social change, Knox said the challenge is to use knowledge about the local system to create a social movement or revolution, and in Algoma’s case it is the community’s children who can create that revolution. From the studies Knox and his colleagues have done, he believes there are six drivers to creating a successful social movement (see Figure 3-3), starting with developing transformational leadership that can create a unified, passionate vision and message that can rally the community and build a coalition for collective impact.

To build momentum capable of activating the community, Live Algoma staff gave activation team members invitations to a celebratory

SOURCE: VanLanen and Knox presentation, December 8, 2016.

event that they could give to anyone in the community who they believed were bright spots in Algoma. “It was an incredible experience filled with tears,” Knox said. “People who lived their entire lives in Algoma did not know who some of the bright spots were.” With the community activated, it is then possible to build the comprehensive engine for community change using a variety of tools and resources that will produce the social revolution needed to create a healthy community.

VanLanen then discussed the third domain, which is having critical conversations. In Algoma, more than 50 percent of the population is age 55 and older, and this creates the challenge of including youth voices in community conversations. Live Algoma worked to build the capacity of the community’s youth to develop the language needed to get their ideas heard in the community, and the result has been that adult community leaders, including the mayor and other key stakeholders, have had critical conversations with the youth about the challenges they face and possible solutions to those challenges. “When adults listen to the youth, it ignites them and activates them, and they become change agents in our community,” VanLanen said. “Having critical conversations about what matters to them, and not us telling them what should matter to them or us not fixing a problem that we see, is very important in our community.” To help build relationships between the youth and adults of the community, Algoma attached its community wellness center to the local high school.

To the same framework of leading from within, leading together, and leading for outcomes that the TLHIP team described, VanLanen and her colleagues added a fourth component, leading for equity. In the past, the community she works with typically did not hear or use the term “equity,” she said, but equity is now a central theme in every decision the community makes, whether in terms of who is and is not thriving or in terms of whose voice is and is not heard at the table. As an example, VanLanen spoke of how the director of the school’s technology department took equity into consideration when he established the Community Fab Labs. This community resource makes tools accessible to those who do not have them at home, with students teaching community members how to use these tools. This, VanLanen said, is one small example of equity in action.

VanLanen said that she sees her role as a capacity builder who can supply tools and resources and identify partners in the community who can help create and enact solutions. When her team brings different voices in the community to the table, they do not present data and tell the community members what needs to be fixed. Instead, they ask what the community members want to work on to create change that can improve health and well-being. Examples of change that have resulted from this process include the following:

- More than 100 school-age volunteers showed up to clean the city’s Crescent Beach, documenting collections of trash and increasing awareness of what waste can do to the area’s ecology.

- More than 100 people have been educated on the nutritional principles of eating more fruits and vegetables, cutting out processed foods, eating healthy proteins and fats, and avoiding sugary beverages. In a pre- and post-survey of participants in the program, 100 percent of the individuals reported improvements in at least one nutritional principle.

- Adding a new salad bar in the school cafeteria resulted in a 450 percent increase in weekly average vegetable consumption and in 1 year contributed to an increase in baseline indicators from 35/100 to 51/100 on the Smarter Lunchroom assessment scorecard.16

- In 2016 the community built a new ice rink to take advantage of Algoma’s cold weather climate and encourage locals to get out and move in winter. This project was so successful that the community is now working on building a walking and biking trail.

- A student who learned the “Plan, Do, Act, Study” process inspired teachers to learn it, too, and 33 school district staff are now using this improvement science process in their work.

VanLanen said that these success stories create momentum for change in the community, and program staff make a point of stressing that community members developed these projects. “We try hard not to talk solely about the problems but who are the people solving them and who the bright spots are in our community,” she said. Identifying these bright spots and the things that community members are proud of pulls the community together, she explained, and turns challenges into opportunities for improvement. Live Algoma strives to keep community engagement at the center of the change process. “We always say we have an open invitation,” VanLanen said. “Some people are ready, some people are not, but there is always an open invitation.”

For example, what began as an initiative to teach hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) at a high school basketball game soon became a community-wide effort that had students using improvement science to teach CPR to more than 800 individuals in the community, including at a Green Bay Packers football game and within the Hispanic community. A youth-generated idea on how to teach preventive methods to address the high rate of obesity in the community grew from train-

___________________

16 For more information, go to http://smarterlunchrooms.org/resource/lunchroom-self-assessment-score-card (accessed March 31, 2017).

ing 45 people to training more than 1,000 individuals, one-third of the Algoma population. “I’m astonished at what community members can do, and it is not about what money we need,” VanLanen said. “It is about who we need to partner with in order to make this happen.” VanLanen emphasized the importance of including different voices at the table to drive community change. In Algoma, community members have benefited, for example, from having a systems-level thinker such as Knox at the table, someone who can be a community engager and activator, and from having residents who can bring their lived experiences.

Knox briefly discussed the difference between problem solving and solution-based thinking. Solution-based thinking is about dreaming of a possible future situation and then working toward that dream rather than solving a particular problem. Knox explained that design thinking, a form of solution-based thinking, is a formal method of practical, creative resolution of problems and the creation of solutions with the intention of obtaining an improved future result. The examples VanLanen gave show the power of working together to achieve a dream of creating a healthier, more equitable community.

With regard to the final domain, scale and spread, Knox said it is important to identify the human, organization, financial, policy, information, and communication resources in a community. The issue with scale, Knox said, is that the community needs to think about the infrastructure that needs to be built and to support the work that the community members are trying to do. Leaders need to be thinking about the future and build the necessary infrastructure ahead of time. If that is not accomplished, the community-building process will hit a wall because the infrastructure is not in place to support it, he said.

VanLanen closed the Live Algoma presentation by discussing what a group of sixth-grade students who were taught improvement science by the graduating seniors mentioned in the CPR story accomplished in the community. Three of these sixth-graders decided they wanted to eliminate food insecurity. By using what their older peers had taught them, they convened a meeting with 23 key stakeholders in the community. The result of this meeting was that the two local grocery stores now donate all of their bruised apples and other “ugly produce” to the school to serve as healthy snacks. “It is just such an empowering story because it was not the adults spreading these tools,” VanLanen said. It was the high school seniors saying, “We cannot keep these things to ourselves. We have to spread it to the younger generation.”

Stout added that Live Algoma is now sharing its work and successes with five other nearby communities in order to reduce poverty and increase equity. She noted that one lesson 100 Million Healthier Lives has learned is to “think about collective impact as not simply a group of formal

leaders coming together in a room, setting some ideas and priorities, and moving them forward” but instead as a much more generative, living, and dynamic process of transforming the lives of people and communities together. Through its work, 100 Million Healthier Lives has identified three important characteristics for success in communities of solution: how people in a community relate to each other, how the community creates abundance, and how the community approaches the change process. Participants briefly discussed at their tables the handout on communities of solution (see Appendix C) and provided written comments and questions that were generated during their discussions.

DISCUSSION

Stout began the discussion with the comment that one thing that 100 Million Healthier Lives is learning is that unleashing the power of communities requires unleashing the power of change makers at every level to create change together. “We often tend to think of change across sectors, but it is really change across levels along with everyone who is a piece of the solution,” Stout said.

Sanne Magnan asked Douglas and Varano if their initial focus on safety brought different partners into the conversation about improving community health outcomes. Douglas replied that the Community Benefit District, which is a body funded through a small tax on businesses in and around the Tenderloin, as well as some of the technology firms that have moved into the area, are now partners and have even taken over the Tenderloin Safe Passage Program. The Community Benefit District speaks for the business community and that, he said, has been an important voice to add to that of nonprofits and public health when speaking to various stakeholders in the community. He also noted the strong relationship that TLHIP has developed with the San Francisco Police Department around Boeddeker Park. There is now a police station diagonally across from the park, and a police officer spends time daily in the park. “That is critical because that officer gets to know the community in a different way,” Douglas said. In addition, the focus on safety has brought groups like the YMCA, a local church, and the Golden Gate Safety Group into the conversation and has enabled them to play a role in community safety. Varano added that with safety serving as the common denominator, individual business owners have become more involved in the community.

Karen Ben-Moshe from the California Health in All Policies Task Force asked if TLHIP was thinking about gentrification and if it was doing anything to make sure the benefits accruing in the Tenderloin continue to benefit the residents of that area. Gentrification is a hot topic in San Francisco, Douglas said. TLHIP has funded a facilitator to work with a

group called Development Without Displacement and craft a series of recommendations and approaches that the community can implement to support the residents in the Tenderloin. He also said that a Tenderloin resident on TLHIP’s steering committee has pointed out that the neighborhood’s residents want a good neighborhood and opportunities to live and grow together with new residents.

Johnathan Heller of Oakland-based Human Impact Partners noted that the first panel spoke about the need to tackle power, oppression, and racism head on, and he asked how TLHIP was doing that. Varano replied that in September 2016 there were a number of violent acts in the community and for the first time in her experience, city officials approached them immediately to ask how they could help the Tenderloin. At the same time, community residents were turning to TLHIP with that same question. TLHIP convened a community gathering that included a room full of social service providers, concerned residents, and government officials who addressed head-on issues of race and power, in part because the term “safety” may operate euphemistically for racism in the community, Varano said. Douglas added that this is a difficult conversation and it requires being uncomfortable. Stout commented that structural racism is easy to name, but hard to dismantle. Doing so, she said, requires creating spaces where people can begin that conversation with one another, map out the system underlying structural racism, and then think about how to work systematically to disrupt it. Much of the effort she and her colleagues have been involved in over the past 6 to 9 months has been focused on how to do justice to addressing inequity.

Ben-Moshe asked the panelists to comment on how they define community, whether geographically or demographically, and how large or small a community can be. Knox replied that community can be defined in different ways. One community he worked with was created around getting disabled individuals involved in athletic activities. An inner-city school or a company can be a community, and so can an entire city. Knox noted that he and VanLanen gave presentations on Sweden and Scotland, where those entire nations were the community. The defining characteristic, he said, is that a community is the population that needs to come together to accomplish a purpose and to create vision and passion around that purpose.

Douglas added that for him, community is an organic entity that can change. “Sometimes, people identify with the community and sometimes that changes,” he said. In the case of TLHIP, community was defined as a neighborhood for grant-funding purposes, and even that can be complicated because a neighborhood can be defined in various ways—for example, by zip code or specific streets. Douglas said that one difficult conversation that took place with residents of the Tenderloin was con-

cerned with whether to include homeless individuals in the community, and the answer was yes. “That was a very important point to discuss as a community,” he said. Stout said that 100 Million Healthier Lives thinks of two types of communities: network communities in which a group of people have something in common, and place-based communities that have a set of structures, systems, and functions and a group of people working in the context of a place.

Brian Russell asked the panelists if they could reconcile the two panels. The earlier panelists (see Chapter 2) pointed to the need to address the fact that people can come to the table feeling they are not fully recognized, they are dehumanized, or they are characterized as the problem that needs to change. The second panel, by contrast, seemed to be largely about how once people come together, it would be possible to facilitate a positive, solution-oriented collective impact conversation. VanLanen answered that an important factor is to lead from within before coming together with others and to ask where one stands, what questions one has, and what privileges one has. People need to build their capacities and language. “Language matters,” she said. “People need a language to talk about what they are dealing with inside.” Key stakeholders and community members with lived experiences need to build their capacity for having these conversations. Douglas agreed that language is important and said that “if we are not hearing discussions around structural racism and who has power in our community, then I do not think we have the right people at the table.”

Stout said that her program teaches skills that help create conversations in safe spaces. This process starts by having people introduce themselves, telling the stories of their community, and listing their gifts and their habits of the heart—all of which is designed to start giving the various participants an appreciation of otherness and cohesiveness. Participants in this process take walks together and share their stories, their successes and failures, and where they have failed forward and had their hearts lifted. They learn how to build trust and talk about -isms. “It is about beginning to create those conversations from a place of human interconnectedness,” Stout said. When participants leave this training, their first task is to build a plan of engagement for the different people in their community who need to be on a problem-solving team, including system leaders, community connectors, and the community members with lived experiences. She commented that this is not a static process, but one that keeps building on who is in the room and how their perspectives help create solutions.

Knox said that he thought there were many similarities between the presentations of the first and second panels. Listening to the morning panels, he said, he heard people understanding their communities and the

dynamics that make the community what it is. He heard about creating and driving a social movement at a grassroots level, critical conversations, and co-creation.

An unidentified participant asked how to hold these conversations if the community has the prevalent belief that the best way to have long lives and safe lives is for everybody in that community to have an assault weapon or to get rid of government safety regulations. VanLanen replied that no matter where the community is, it is imperative to meet the community there and understand why it has those beliefs. Varano agreed that the power of listening and being present are critical and said it is important not to enter the conversation with assumptions and answers. She recounted one of TLHIP’s fail forward experiences. The members would announce that TLHIP had money and invite others to join them in unearthing solutions. That process yielded a number of disparate ideas, she said, and it failed. Now, the approach is to come in as a co-creator, a supporter, and a cheerleader. Douglas said that there were strongly held beliefs in the Tenderloin neighborhood about injection drug use that needed to be heard and considered, and that required difficult conversations. However, by listening to one another, the community over the course of 2 years has come to agree on a common set of potential solutions. “It is an evolution of the way that you think, but understanding the humanity in people and being able to find some common ground is critical.” Stout added that stories from community members are crucial to creating a common vision.

Bridget Kelly from Bridging Health and Community said that two themes came out of discussions she had with other participants at her table (see Appendix C). The first was that it is not just community members who have lived experiences they bring to the table; community leaders do as well. “It seems like that is not an us-and-them thing, but really a core to everyone who is participating,” she said. The second theme was that perhaps the dynamic process and healthy struggle that develops from these relationships are outcomes, as opposed to metrics and indicators, in that they can demonstrate there has been a shift in the power dynamics of the community. Stout agreed with this second theme and said that 100 Million Healthier Lives has a metric for that. In fact, she said, the program does not define the outcomes by which it will judge a community to be successful. The program has a metrics database called Measure What Matters from which community members can choose the metrics they feel are important for measuring their successes, whether it is the percentage of ugly fruits and vegetables donated to schools or people feeling safe in the process of community engagement. Knox said he agreed wholeheartedly about the importance of letting the community define what is important and then helping the community set up the appropriate

measurements. VanLanen said that when she first started her work with Live Algoma, her idea was that obesity was the problem that needed to be addressed, but after partnering with community members, it became clear that the community thought the biggest problem was a dream deficit regarding future possibilities, particularly among the community’s youth.

With regard to Kelly’s first theme, Stout acknowledged its importance and said that she would think about it more. She added that she thinks that part of what she and her colleagues want to convey is that community members need to be included in creating the solutions—and that the experiences of people who have lived with a particular condition the community is trying to change (e.g., homelessness or joblessness) offer real insight into what the solutions might be. The intention, Stout said, is to recognize the experience that community members have in creating solutions.

This page intentionally left blank.