5

Living with Fire: State of the Science around Fire-Adapted Communities

The second panel turned the attention of the workshop participants to the social-science research on living with fire. The four presentations were followed by a discussion session moderated by planning committee member Jeffrey Rubin.

UNDERSTANDING THE WILDFIRE POLICY CONTEXT: WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Toddi A. Steelman, University of Saskatchewan

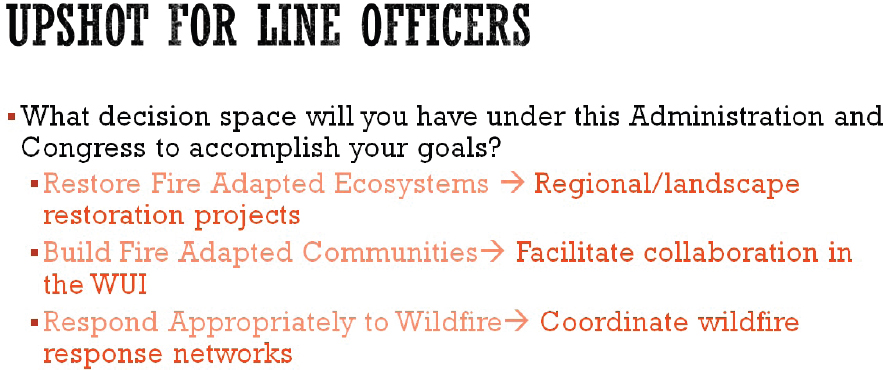

Steelman began by saying that she prepared her presentation from the perspective of what a line officer in the Forest Service needs to know in order to work effectively the 2017 fire season and for future fire seasons. The main framing question is: What kind of decision space will line officers have under the current presidential administration and Congress to accomplish their given goals? Steelman took the goals of the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy as given because there is good understanding of and agreement on them. They are

- Restore fire-adapted ecosystems,

- Build fire-adapted communities, and

- Respond appropriately to wildfire.

As was established in earlier presentations, the current problem is larger and more intense wildfire, and the challenge of managing it is in part due to climate change. Larger, more intense fires are being seen in North and South America, including in places where they are not expected (for example, the November 2016 fire in Gatlinburg, Tennessee). The system leading to these fires is complex, and a framework is needed to understand some of that complexity.

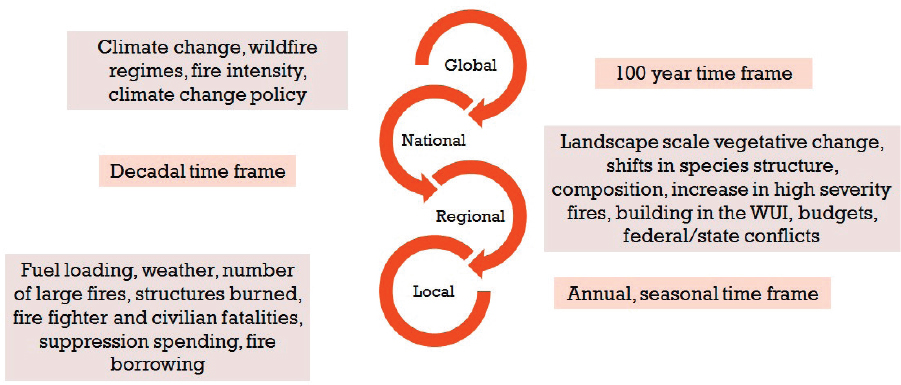

Complexity occurs at temporal and spatial scales. Spatial complexity is occurring at the global, national, regional, and local scales, and those different scales interact with one

another. Temporally, complexity takes place within seasons, decades, and centuries. Filling in some of the events and conditions that occur on these spatial and temporal scales begins to flesh out an integrative framework of how wildland fire science can be understood (Figure 5-1). It brings together some of the social, biophysical, and engineering sciences to lend greater understanding to complexity involved in the whole system. For example, at a global or a national level, the interplay of social and ecological components is apparent in climate change, wildland fire regimes, and fire intensity as well as in how climate change policy begins to be a response to those three components. At the national and regional scales, the social and ecological interplay is evident via landscape-scale vegetation changes, fire severity, shifts in species structure, and conflicts between state and federal budgets. The wildland–urban interface (WUI) and how it has developed over the past several decades to create the problems that are currently being experienced is another component through which the complexity of social and ecological interplay can be observed and understood. Finally, all these components come to bear at the local scale, where the line officer has to deal with everything from fuel loading and weather to several large fires each season, evacuees, death, and destroyed structures. Funding issues for fire suppression and funds diverted from other management priorities to fire suppression are socioeconomic pieces that come into play at the local scale.

Viewing the problem through this framework requires thinking in a more anticipatory way. What would anticipatory governance and anticipatory management of wildland fire look like today and into the future? That is, what can be expected related to wildland fire in the next several years? As previously stated, it is expected that climate change and large fires are going to persist. Steelman also expected that, under the Trump administration, little action on climate change would be taken at the national or international scale. Therefore, decision space should not be devoted to thinking about solutions related to national or international climate change action. Similarly, the budget blueprint released by the Trump administration on March 16, 2017, called for a $53 billion cut in discretionary spending, which will affect the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Department of the Interior, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency

SOURCE: Steelman, slide 5.

within in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. If such cuts are enacted, they will have consequences for fire management in the upcoming years. Because the budget had not yet been approved by Congress, Steelman said there would be some decision space to establish some priorities until the budget’s finalization in October 2017.

There will also be increased pressure on state and local budgets. State budgets will be particularly affected by health care spending requirements and infrastructure needs. At the local level, the expiration in 2015 of the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act means that 700 rural counties with national forest land received the last transfer of federal funding for public schools, roads, and other municipal needs authorized under that act in the fall of 2016. Competing priorities and declining funds will have consequences for how wildland fire is managed at the local level.

How are line officers going to manage forests under these leaner fiscal conditions and environmental and social complexities? Where is the fire science and management community going to find the decision space to meet the goals of restoring fire-adapted ecosystems, building fire-adapted communities, and responding appropriately to wildfire?

With regard to the first goal, the fire science and management community can look to some existing projects that are increasing the pace of restoration at the regional scale. Steelman gave three examples of such projects: the Forest Resiliency Project of the Blue Mountains Restoration Strategy Team in Oregon and Washington,1 the Four Forest Restoration Initiative in Arizona,2 and the From Forests to Faucets collaboration between the Forest Service and Denver Water.3 Congressional delegations need to be made aware of the importance of working at this regional scale over the timeframe of a decade. If progress is not made regionally over this period of time, no progress will be made at the local scale.

To build fire-adapted communities, more collaboration is needed within the WUI. Line officers do not have much power when it comes to dealing with private land, but they do have Community Wildfire Protection Plans and Good Neighbor Agreements. Steelman thought authorization for these types of collaborative approaches would be politically appealing to the 115th Congress. Line officers and people at the local level also have stewardship contracting available as a tool.

To meet the goal of responding appropriately to wildland fire, line officers seek to lose as few lives as possible to fire, protect values at risk, and manage risk appropriately. An option for meeting this goal is to coordinate a wildland response network, which brings together local-level entities—including fire and disaster management officials, local government representatives, and the media—before a wildland fire happens so they can perform effectively and collaboratively during a fire. Too often fire management is thought about as only federal, state, and local fire services, but effective management actually requires much broader participation for frontline action, particularly when trying to manage something like a big box burn. A big box burn may be an opportunity to put more fire back on the landscape if a fire happens on a national forest, but it cannot be done effectively if a network of local entities has not been established before that fire.

In conclusion, Steelman said that there is a framework to think about spatial and temporal complexity. When thinking strategically and tactically about the complexity that exists for line officers in national forests, three areas within this framework where Steelman

___________________

1 Blue Mountains Forest Resiliency Project. Available at https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r6/landmanagement/resourcemanagement/?cid=stelprd3852678. Accessed July 3, 2017.

2 The Four Forest Restoration Initiative. Available at https://www.fs.usda.gov/4fri. Accessed July 3, 2017.

3 From Forests to Faucets partnership renewed and expanded. Available at http://csfs.colostate.edu/2017/02/28/forests-faucets-partnership-renewed-expanded/. Accessed July 3, 2017.

SOURCE: Steelman, slide 12.

thought action could be taken in the coming years are: (1) regional/landscape restoration projects, (2) coordinated wildfire response networks, and (3) collaboration in the WUI (Figure 5-2).

FACILITATING ADAPTATION: COMMUNITY VARIATION IN THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH AND RESPONSE TO WILDLAND FIRE

Travis Paveglio, University of Idaho

Paveglio’s presentation focused on social diversity in the WUI. Fire can occur in a variety of places, but Paveglio pointed out that there is a tremendous amount of social diversity in places affected by fire, and that diversity is often overlooked. Additionally, the people living in areas affected by fire are changing. They may have different abilities or perspectives about how they can work with land managers, agencies, or nongovernmental organizations to successfully live with fire.

His overarching point was there is no one way to live with fire. In a number of studies across the western United States, it has been observed that people will have to adapt in different ways. People living in communities that need to adapt to fire first need to be understood before science can be tailored in a way that fosters an agreed-upon approach within the community to living with fire. Otherwise, interventions will be ineffective.

Paveglio’s work has concentrated on understanding and characterizing the social diversity in communities living with fire. What does that social diversity mean when people may have differing abilities to reduce fuels on their properties or when they may have different capabilities for writing grants to get money for fire management or adaptation activities? How does that social diversity affect whether they stay and defend their properties, as they often do in many of the places that he has studied? There is a tendency in social sciences on wildfire to see “the public” as one singular entity, but it usually is not. There are many diverse views and communities within “the public”; therefore, the unit to address when tailoring messages is the one in which change can be achieved. Paveglio’s research group

defines the unit (community) as people who will come together, care about an area, and propose and carry out some type of action. The unit size can vary, and it can fragment over time as a landscape changes. For example, a community could be timber dependent or range dependent, but over time those activities could decrease and in their stead, more people could move in, creating smaller communities that do not interact in the way the timber or range dependent community did.

To understand this social diversity and the ability of social structures of communities to change, Paveglio designed a framework of characteristics to represent diversity in a given place (Paveglio et al., 2009). Demographic and structural characteristics—for example, peoples’ income levels, their willingness to pay, and how old they are—are often examined because data exist for those types of diversity. Those characteristics are important, but they do not capture other components of social diversity, such as

- The ability of a unit (community) to access and adapt scientific and technical knowledge to local circumstances,

- The ability of people to work together in effective networks, and

- The place-based knowledge and experience held within the unit, including traditional ecological knowledge that encompasses a long-term understanding of burning in those places.

Paveglio and Edgeley (2017) have developed 22 characteristics that nest within this framework. Together they create a corpus of characteristics that managers can use to go to any community living with fire and ask, “Which of these characteristics intersect and how does the intersection lead to different types of adaptation within the community?” The characteristics of social diversity might not always intersect in a way that facilitates adaptive capacity. In such a case, adaptive capacity development might need to be undertaken, which is why is it important to understand the capability of the community first before conducting additional science because people may not use modeling outputs the same way or they may not use the same types of fire-wise programs.

An analysis of 20 years of case studies has identified four different archetype communities across the western United States (Figure 5-3). Formalized suburban communities are those that tend to be small in area, such as a gated community or a community with a homeowners’ association, in which standards for maintaining space free of fuels around a home or structure could be created. High-amenity/high-resource communities are those that have more people with second homes. People in these communities may be more inclined to focus on fuels reduction for landscape health or on actions that will sustain recreation opportunities. Rural lifestyle communities often have diffuse patterns, and people in these communities may be more interested in privacy. A difficulty in conducting prescribed burns or creating collective fuel breaks in these types of communities is that they often want to have wildlife habitat or traditional activities, like hunting, near their homes. Working land-

SOURCE: Paveglio, slide 4.

scape communities have people who have a tremendous amount of local knowledge and who probably have fought fire themselves. Their knowledge can be utilized; this has been seen in some studies with range and fire protection associations, where ranchers have interfaced with incident commanders and provided initial fire suppression on remote public lands.

Different policies and programs will be more effective with the people in these archetype communities to help them in their adaptive capacity. The framework designed by Paveglio can be used to explain why it is that people in one type community find a certain pathway to be the most effective course for adaptation. The framework can also be used to decipher the best way to communicate messages about adaptation to them and to identify the data they need to sustain their communities. The goal is to work with a community’s culture, not against it. Communities need to be able to choose their own pathways to living with fire, and they need to have the tools to characterize their conditions in order to communicate why they need to adapt the way they do. They also need to be able to work with partners, if desired, such as federal agencies or nongovernmental organizations. In some cases, communities advocate that no government involvement is necessary for them to adapt to living with fire.

Paveglio and colleagues are currently testing different policies—such as Community Wildfire Protection Plans at different scales, incentives, and matching grants—across the community archetypes to

- See how policies may be better supported in some places than others, and

- Work on co-developing the type of knowledge needed to be able to identify what types of policies will work in which types of community.

This research is needed because fire-resilient landscapes need fire-adaptive communities within them, and people are a component of the landscape that has to be understood. People are fragmenting landscapes, and their views about the way they are managing land, their attachments to a place, and the scale at which they want management (federal, regional, or local) are all changing. The social component of fire (people and the type of community) affects the fuels that end up being treated or burned (intentionally or not), the ways people respond to fire, whether or not there will be conflict after fire, and whether or not there is support and use of local knowledge in effective ways.

The framework is not just useful to scientists or fire managers. If people can self-identify with the social diversity characteristics in the framework and managers can also use them to quickly understand that context, then everyone has consistent data. For managers, this framework is a way to recognize community characteristics and a tool to identify effective strategies for working with communities that have those characteristics. It also builds from prediction to a “science of practice,” in which the identification of effective strategies takes place through work with communities, rather than using existing theories or tests to prove that there is a problem.

In the end, there are no theories for community adaptation to wildfire in social science. Most of the theories that exist have been taken from psychological or social theories. Paveglio stated that he and his colleagues are trying to build a theory that allows for a quick understanding of the social diversity of communities living with fire and what it means for differential adaptation. Because policies, interventions, and management strategies are effective only if people adopt them, understanding that diversity is important. Building policies, inventions, and management strategies with the idea that they will be adopted if the community is convinced about the proposed course or educated to see the utility of the suggested adaptation will not work. In the future, Paveglio added, variable assessments will be needed to understand

- How fire-adapted communities are going to adapt differently depending on their archetype,

- What incentives, policies, and strategies will get people to respond to fire depending on their archetype, and

- How incentives, policies, and strategies can be equitably deployed across different types of communities.

These types of assessments will help information flow from communities to managers and policymakers and improve management across boundaries and across different, diverse people.

TRANSLATING FIRE SCIENCE INTO FIRE MANAGEMENT

J. Kevin Hiers, Tall Timbers Research Station & Land Conservancy

Before he was a wildland fire scientist at Tall Timbers Research Station, Hiers was a land manager at Eglin Air Force Base near Valparaiso, Florida, which has one of the nation’s largest fire management programs. With his mentor James Furman, the U.S Forest Service Liaison at Eglin’s Wildland Fire Center, Hiers set over 40,000 hectares (100,000 acres) of prescribed fire each year and fought an additional 100 wildfires annually. Whether a manager operates on an air force base or a national forest, it is worthwhile to step back and understand the context of a location because, wherever that location is, a policy management trap exists when it comes to fire. That trap encompasses 100 years of fire suppression and fuel accumulation as well as the growing WUI. For example, in Florida, the abundance of homes and other infrastructure built along the coast means that the WUI has become a central consideration of any plan for prescribed fire. In the West, the WUI has caused fuels treatments to become the focus of fire management actions. This attention to the WUI rather than forest or ecosystem health leads to limitations in desired landscape outcomes.

Hiers noted that adequate resources do not exist to appropriately address the United States’ fire problem. Inordinate attention to the WUI exacerbates the problem because it creates the policy management trap in which fire managers put out easy fires and choose to set hard ones. These management actions mean that the capacity to appropriately treat the greater fire problem in the United States is continually diminished because of the amount of resources devoted to managing fires on the dynamic, sinuous edge of the WUI. The dearth of resources to treat the greater fire problem restricts treatments to small spatial scales, which are typically ineffective in preventing or mitigating large fires. Traditional fire science and management approaches cannot solve this wicked problem.

Hiers has spent much of his career at another interface, that is, the fire science–management interface. Fire managers are a diverse group and include prescribed burners of privately held land, federal firefighters, and state suppression agencies. The diversity represents both a challenge and an opportunity for translating science. However, all managers rely on experience to address uncertainty and to address fire behavior and fire management objectives. Because they rely on experience, trial and error are important; however, fire and prescribed burning occur today in a society that has little capacity to tolerate error, Hiers said.

Fire scientists are a diverse group as well and come from disciplines as varied as meteorology, physics, forestry, ecology, and, increasingly, the social sciences. In an attempt to be relevant, fire scientists often are tool-focused and recommendation-focused so that they can tell managers how to better manage their land. The unintended consequence is that decision space is often constrained in this increasingly complex world. When mistakes are made by

quantifying the obvious rather than focusing on what managers need to know, little science is translated into management actions.

Because Hiers has spent much of his career on this border between fire science and fire management, he emphasized a few characteristics that are important barriers to overcome. First, managers rely on experience as the currency of credibility. This experiential learning is different from structured learning. The scientific community, with its incentive to publish papers, has dialogs and arguments in the peer-reviewed literature; however, that conversation does not always translate well to on-the-ground experience. Second, managers have specific circumstances to deal with—the fire of the day that has a particular set of management objectives, topography of fuels, and atmospheric conditions—whereas scientists seek generality in their world view. Generalization changes scientists’ understanding of managers’ risks. Third, the complexity in fire management versus the orientation of fire science around specific disciplines increases the challenge of applying science to management. For example, when a prescribed fire is set in the WUI, the manager’s job is on the line and he or she has to integrate all of the different disciplines of fire science into that day’s burn. As fire scientists dive deeper into the depths of particular disciplines, the ability of managers to integrate the findings of research from these different areas of expertise and apply them to a specific burn becomes more and more difficult.

A different approach is needed. First, translational fire science, which is process-oriented not tool-focused, is needed. Hiers posited that solutions to the United States’ fire problem will come from long-term, shared experiences where scientists are on the fires with managers, providing the circumstances for each group to become fluent with the other. Second, fire science outcomes must begin to address uncertainty, he said, rather than what is already known, and focus on fires that can be controlled, like prescribed burns. Even for prescribed burning in the Southeast, tools are still needed to develop objectives and prescription parameters. Third, the disciplinary breadth of fire science needs to be expanded to social scientists. Many of the solutions discussed at the workshop were outside of the traditional realm of fire science expertise. Hiers commented how important it was to have social scientists present at the workshop and how their participation in fire science and management is absolutely critical. More incentives need to be provided for social scientists to participate in and contribute to solutions.

Many building blocks exist for moving toward this new approach, including prescribed fire councils, regional fire exchanges through the Joint Fire Science Program, and the Prescribed Fire Science Consortium. Hiers emphasized that when managers and scientists burn and manage fires together, they learn together. One of the premier National Interagency Prescribed Fire Training Center courses is an agency administrator course, which brings the line officers into a context where they see what managers face every day. Shared experiences like the one provided in the course are key, but such mentorship programs are lacking. Formal adoption of shared experience as a strategy has yet to occur, and agency leadership is needed to provide incentives for scientists to participate in an experiential way.

Hiers concluded with a case study at Eglin Air Force Base, where he and Furman unwittingly created opportunities for shared experience. When they arrived in the late 1990s, they found an Air Force base with 200,000 hectares (500,000 acres) of longleaf pine that needed frequent fire. The base already had a long-term commitment to relationships with researchers, primarily in the ecology and wildlife science fields. However, the existing program was wholly inadequate in its capacity to conduct prescribed burns on the scale necessary; only 13,700 hectares (34,000 acres) were being burned each year on a 200,000-hectare landscape that needed to burn every 2–3 years. To address this situation, Furman and Hiers built upon the research–management relationship that already existed

and, as more research was conducted on the base, they gained site-specific solutions to some of the problems. At the same time, scientists and managers experienced fire together on the fire line, and individuals who had never been on the line were able to see what managers faced, including the practical constraints of conducting research.

This collaboration also assisted with putting in place a burn prioritization process. There was not enough capacity in the fire management program on the base to burn the target amount of area each year. Therefore, Furman and Hiers focused on the worst habitat and, rather than disaggregating fuel treatments, they worked with fire managers, fire researchers, and wildlife biologists to aggregate treatments. They hoped that by burning and maintaining the best quality habitat, the fire-dependent ecosystems in these locations would slowly grow capacity over time. Ten years later, the treatment capacity had tripled, and the goal of burning over 40,000 hectares (100,000 acres) a year is frequently met.

Regional solutions with innovative, dynamic, and robust fire management–science partnerships can play a key role in addressing the policy management fire trap. More fire is needed on the landscape, not less, and national policies will not work as well as regional policies to introduce that needed fire. Shared experience is the bridge between management and science.

ADAPTING TO WILDFIRE: MOVING BEYOND HOMEOWNER RISK PERCEPTIONS TO TAKING ACTION

Patricia Champ, U.S. Forest Service

Champ’s presentation focused on how to get homeowners to take action to protect their properties from fire. She framed this challenge as a last-mile problem, which is a concept from the literature on supply chain. The last mile is the end of the supply chain where a product is transferred to the customer. The last mile is often the most difficult part of the entire supply chain, and for that reason, it should not be thought about last.

Champ used a bridge to nowhere (based on a TED talk idea by Harvard University economist Sendhil Mullainathan) as a metaphor for the last-mile problem in fire science and management. A great deal of engineering has gone into building the bridge, yet it leads nowhere. Likewise, a century’s worth of fire science has been conducted, resulting in a better understanding of fire behavior and home ignitability. Yet there are still homeowners who do not take action to mitigate the risk posed to their property by fire.

Research finds that, generally, homeowners in the WUI understand that they live in a fire-prone landscape and that they are vulnerable to losing their home. However, taking action is not simple, Champ said. First, as Paveglio discussed, community context matters. Second, homeowners need specific information to take action. Therefore, the general concept of the home ignition zone (Figure 5-4) needs to be made applicable to the particular hazards on an individual homeowner’s parcel, such as the trees near a wood deck. Third, multiple interactions with the homeowner are required to induce action; one message to a homeowner about defensible space will not lead to behavioral change. The homeowner needs to interact on his or her property with someone he or she trusts, such as a volunteer from the fire department, a local wildfire council member, or a state forest service representative.

To find ways to solve the last-mile problem of homeowners taking action, Champ is part of an interdisciplinary research collaboration team called Wildfire Research (WiRē), which focuses on homeowner wildfire risk mitigation and community wildfire adaptedness. WiRē serves as a model of joining research and practice. The personnel come from three different federal agencies: the Forest Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Bureau

SOURCE: Champ, slide 4. Image courtesy of the Colorado State Forest Service.

of Land Management. The University of Colorado, Boulder, is also a partner as are two wildfire councils in Colorado. As of early 2017, most of WiRē’s work had been conducted in Colorado, but the team expected to work in other locations soon.

As of March 2017, WiRē had collected systematic data in 87 Coloradan communities. To generate the data, the practitioners conduct a rapid risk assessment for every parcel that has a structure in the community. This assessment is based on 11 attributes, such as where the parcel sits in the landscape and the vegetation on the parcel. Some of the attributes relate to the structure that is on the parcel. At the same time, the local community conducts social surveys. These surveys help WiRē learn about the people who live on the assessed parcels.

WiRē has used the collected data to understand the effectiveness of different kinds of nudges. Nudges are messaging efforts that seek to encourage behavioral change. The WiRē team designed an experiment with three nudges and ran it in a Coloradan community where homeowners had not taken mitigation measures to protect their homes. The community had a cost-share program in place for years to encourage such measures, but no one had taken advantage of it.

In each nudge in the experiment, a letter was sent out to homeowners in the community. In the first group, homeowners were told in the letter about their community level of wildfire risk. That information comes from the century of research on how to conduct risk assessment. In the second group, homeowners were told about their community level of risk and their parcel level of risk. That information builds on the pioneering work that Jack Cohen

did within the Forest Service’s research arm on the home ignition zone.4 In the third group, a social norm piece was added to the letter. Homeowners were told about their community level of risk, their parcel level of risk, and the level of risk of their 10 nearest neighbors. Homeowners could respond to the letter in one of three ways: (1) they could go to a website that was individualized with risk assessment data for their parcel of land so they could see how their parcel was rated on the 11 attributes; (2) they could call the West Region Wildfire Council, the practitioner part of this venture; or (3) they could attend a community meeting.

WiRē’s results had not been published at the time of the workshop, but the preliminary data suggest that response rates were good across all three groups. More importantly, when it comes to the last-mile problem, community members undertook more defensible space projects in the last 4 months of 2016 (after the letters were mailed) than they had in the 5 previous years combined. Though the absolute number of projects was small (17 as of the end of 2016), this increase was a substantial change in the community compared to the years before the nudge experiment. Champ and the rest of the WiRē team planned to follow up with homeowners in 2017.

In closing, Champ posed the question: How can a century’s worth of fire science be used to help homeowners adapt and live with wildfire? One way is to unite research and practice, which might look different depending on a scientist’s wheelhouse. Another way is to understand the importance of personal relationships. The relationships matter within the WiRē team; for example, Champ has been working with BLM for over 12 years. Relationships also matter when working with homeowners to build their trust and induce action. Finally, Champ reminded the audience not to think of the last mile last.

MODERATED DISCUSSION

A participant asked if messaging to the public should communicate that mechanical treatment (such as thinning) is needed along with prescribed burning and whether that message needs to be communicated at the middle mile, not just the last mile. Champ responded that often when the fire science community talks about the public, their notions of who or what the public is are not supported by data. Once the social piece has been investigated, it frequently turns out there is more support for fire on the landscape in fire-prone communities than was originally presumed or at least there may be a foothold of support that may grow with more communication from fire scientists and fire managers. However, there has been little research that looks closely at public support for fuels treatments in a specific sense, that is, fuels treatment next to a homeowner’s house or in his or her community. Champ was not sure what the optimal message would be, but that messaging needs to be different depending on the place. For example, there are rural landscapes where burning is used regularly for land management; prescribed burning may not bother the people in these landscapes as it might elsewhere.

Paveglio added that the 22 characteristics in his framework aim to discover different communities’ comfort level with fire on the landscape. In working landscapes, his research has found that people are generally on board with the idea of prescribed burns, but that will not be the case in all places. The tailored message would include planning for where mechanized fuel treatment should occur and where prescribed burning should be done. In another location, depending on the type of people, how they are situated, what their ownership patterns are, and whether or not they work together, a large break in vegetation across

___________________

4 See The Jack Cohen Files. Available at http://www.firewise.org/wildfire-preparedness/wui-home-ignition-research/the-jack-cohen-files.aspx. Accessed July 3, 2017.

an area with wildland fuel might be the correct course of action, and prescribed fire might play a background role in that location. Paveglio and his colleagues are testing tailored incentives for different scenarios, with the hope to develop from this work a range of options that people can choose from to address fire issues. That data will also help researchers understand why a fire-prone community selects a particular course of action. Different approaches can be taken by communities to get to the same ends of fire adaptation, for example, Community Wildfire Protection Plans, fuel reduction, evacuation planning, and land-use planning. In the end, fire-prone communities need to learn how to live with fire; that will look different in each location.

A viewer of the webcast asked how legislation like the Endangered Species Act or the Wilderness Act affects fire management. Steelman did not anticipate that there would be much appetite in the 115th Congress or in the Trump administration to revise the Endangered Species Act. The situation with greater sage grouse—which was recently a candidate for the endangered species list—will be interesting to watch because managing for species abundance has constrained management of wildfire; however, Steelman did not think the balance of policy objectives currently in place would change in the near future. With regard to the Wilderness Act, Steelman thought that there would be less funding available to protect new areas, either under the jurisdiction of the Forest Service or the U.S. Department of the Interior. Rural communities derive benefits from having federal lands like wilderness areas near them. Ownership of those lands has been contentious in some states but less so in others, which relates to Paveglio’s point that effects are differentiated depending on the community. Steelman doubted that there would be pressure to turn ownership of all the federal lands back to the states simply because it would be too expensive for the states to fight fires on these lands. Therefore, whereas such pressure existed during the Reagan administration, Steelman did not think it would resurface because the states cannot afford the management costs.

Hiers noted that, for fire management at Eglin Air Force Base and several other military installations in the Southeast, the Endangered Species Act was an extremely beneficial tool for reducing wildfire risk on those properties. Fire-dependent endangered species like the red-cockaded woodpecker had large populations on U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) land. The use of prescribed fire was a win–win proposition because it reduced wildfire risk and it managed for the habitat of those endangered species; the management approach can serve as an example for similar situations on land not managed by DOD. Paveglio added that a converse example has occurred in critical greater sage grouse habitat, where the Endangered Species Act was used to protect habitat for sage grouse that was threatened by fire. The use of such a policy tool may not always lead to a fire-resilient landscape, but it directs the actions people take. Communities have some agency5 within the policy space to work toward an end goal however they want and to plan for that goal in ways that meet their needs.

Another participant noted that a lot of research is done on how forests and wildlands burn and on how to improve fire-management practices. However, he has heard little discussion or research about better community planning to address fire risk. What work is being done with regard to community planning, and what agency or group should be encouraging such work? Steelman offered the first response. She said Community Wildfire Protection Plans are one tool available to help communities plan for fire risk. These plans were included in the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003. They are a way for the community in the

___________________

5 In social science, agency is the capacity of individuals or a collective entity to act independently and to make their own free choices.

WUI to come together with the state and federal agency representatives to do comprehensive planning in that interface and prioritize areas where they would like fuel treatment as well as prioritize the values at risk that they would like protected during a large wildland fire. Having been in place for over a decade now, the benefits of those plans are starting to be seen. They demonstrate the importance of putting such types of opportunities in place at many different scales (local, regional, and national) because the desired outcomes take time to come to fruition. Another tool available is a Good Neighbor Agreement, which is a way for federal forest lands to be mechanically treated by state agencies. The state agency can conduct the environmental impact assessment and treat that area right in the WUI. The funding for this program makes it possible for treatment done on the urban side of the interface to be matched by treatment on the federal side of the property. This tandem work creates a fuel break, leading to a landscape that is more fire resilient overall.

Paveglio added that his group has conducted research in which they have taken modeling outputs and created different social vulnerability maps at the parcel level. Those maps are then matched up with some of the barriers to overcoming the last mile that Champ discussed. The result provides information about the perspectives of people in the community, how long they have lived in the area, and from whom they get their information. One of the findings of that work is that most of traditional social vulnerability indicators—both demographic and structural—were not well matched to the western communities included in their research. This mismatch shows a need to look again at how planning might be structured and how those people might set up a system in their communities to address their most important concerns. As an example with regard to values at risk, if an incident commander from out-of-state arrives at a location, he or she may be unfamiliar with the values that community may deem important. There needs to a system or set of steps in place so that when such an incident commander arrives, the community can communicate that they, for example, want to emphasize protection of the grasslands and the forest lands that they (the community) have invested in whereas structures like an old farmhouse can be deprioritized. When this process occurs, most incident commanders prioritize the values that matter to the community as long as the associated actions do not cause any harm to firefighters. Land-use planning can be done in a similar way so that community social norms are prioritized.

Craig Allen asked what is known about public acceptance of smoke from the prescribed burning in the Southeast. Hiers said that smoke clearly is a tremendous impediment to conducting prescribed fire. For example, at Eglin Air Force Base, burning can often only occur when the wind blows to the south (toward the Gulf of Mexico) because of coastal housing developments to the base’s east and west. However, rural communities in the South have grown accustomed to some chronic exposure to smoke, particularly at certain times of the year. In the Red Hills area of Georgia and Florida, the end of quail season (the beginning of March) is followed by 6 weeks of smoke. Everyone in the area knows it is a part of the season. However, the Southeast does not commonly get dense, thick plumes that settle in for days or weeks. Hiers thought communities likely prefer 6 weeks of light smoke to such intense plumes. Some recent large wildfires in the Okefenokee Swamp, particularly the fires of 2007, gave Southeast residents a western-type experience with fire, which is something the region would like to avoid repeating in the future.

Allen followed up on Hiers’ answer, asking if the type of fuels burned in the Southeast contributes to the acceptance of smoke in that region. Paveglio replied that some recent work has been done on that question by Troy Hall at Oregon State University and colleagues, including the development of a photographic guide to assist smoke management (Hyde et al., 2016). Social science needs these types of tools and heuristics, which exist for biophysical science. Just as Stephens had a number of pictures in his presentation of fuel

types that can be quickly recognized, Paveglio wondered if tools and heuristics could be developed so that social conditions or the types of prescriptions for the smoke that people are willing to accept could be quickly recognized. In essence, the same kind of systematic data collection for social science is needed to turn it into usable science.

Champ added that some of her research has looked at the economic cost of wildfire smoke exposure. She has found that the social cost of a large fire can swamp suppression cost, yet much more intellectual energy is devoted to talking about suppression cost. The toolkit available in economics to measure the social costs of smoke is inadequate because the costs that people incur to avoid being exposed to smoke are not considered. Only one economics study in the United States has been done on the cost of averting behavior for wildfire smoke (Richardson et al., 2013). The issue has not received the attention it deserves from researchers. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is starting to explore these economic and behavioral costs and is developing an app to help the agency get a better understanding of the choices people make to avoid or not avoid smoke. That kind of information will help researchers, managers, and policymakers better understand the risk–risk tradeoffs of prescribed fire smoke, which include: when people know smoke is coming, will they leave the area, stay indoors, or choose to be exposed to the smoke?

Paveglio added that the way social impacts of fire are understood is not well developed. In general, the metrics are quantitative, such as the number of structures burned and the cost of suppression. In a 2015 paper (Paveglio et al., 2015), he and his colleagues compiled a list of all the different potential social impacts that could occur; the list was extensive and could be broken down into several categories. More thought needs to be directed at assessing the social impacts of fire on different communities, which includes smoke and health risks. A more comprehensive understanding is needed of what the benefits and the detractions are from fire events.

CONCLUDING REMARKS FROM MORNING SESSION

Dar Roberts, University of California, Santa Barbara

As the chair of the planning committee, Dar Roberts offered some summary thoughts about the morning’s presentations and discussions. Clearly, a great deal has been learned about fire over the last century. However, there is a still a need to improve fire management. As Chief Tidwell noted, that includes working to get more fire back on the landscape, learning to live with more smoke, and improving fire safety. The workshop also featured a great deal of information about the anthropogenic link to today’s fire problem. Humans start most fires. The consequences of fire are not always negative; the challenge is to get the right fires burning in the right places so they can be used to improve ecosystem management. This balance will be increasingly important as climate change puts pressure on ecosystem resilience.

Living with smoke will continue to be a major issue. Even when fire is managed well and prescribed burning is used successfully, mitigating the smoke or getting the public to accept a certain amount of smoke is a challenge connected to fire.

With regard to Chief Tidwell’s call to identify the missing science, Roberts said that one area highlighted in the presentations and discussions was the lack of knowledge about how fires spread. The largely empirical model developed by Rothermel is still the core of almost all work involving fire spread, but there are many metrics that probably could be incorporated into fire spread models. That was just one example of many areas of research identified.