Proceedings of a Workshop

| IN BRIEF | |

|

June 2017 |

Health Communication with Immigrants, Refugees, and Migrant Workers

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

On March 15, 2017, the Roundtable on Health Literacy of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a workshop focused on health communication with people from immigrant, refugee, and migrant worker populations. Bernard Rosof, chief executive officer of Quality in HealthCare Advisory Group, noted in his opening remarks that the increasingly diverse ethnic composition of the U.S. population requires that public health and health care organizations deliver services differently. “We are really looking for approaches that will enable organizations that serve the community to provide all persons with the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions,” he said. He went on to explain that to achieve the aim of providing care that is equitable and does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, language, or socioeconomic status, it is important that health literacy approaches be used to align system demands with individual skills and abilities. The workshop was organized to explore the application of health literacy insights to the issues and challenges associated with addressing the health of immigrants, refugees, and migrant workers. Presentations and panel discussions explored issues of access and services for these populations as well as outreach and action.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

The first panel featured Paul Geltman, medical director of ambulatory care for Franciscan Children’s Hospital and medical director for refugee and immigrant health for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health; Jeffrey Caballero, executive director of the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations; and Henry Perea, former member of the Fresno, California, Board of Supervisors. The panel was moderated by Alicia Fernandez, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and a physician at San Francisco General Hospital. As patients, immigrants, refugees, and migrant workers differ in their legal status and their access to health care, Fernandez stated. Geltman explained that of these three groups, refugees are the only ones who have automatic eligibility for Medicaid for their first 8 months of residence in the United States and, in some states, for 1 year. Perea pointed out that undocumented migrant workers cannot legally access federal health services, but they may be able to access local health services. While these groups differ in terms of legal status, important challenges include language, literacy, culture, and the need for social capital and social support, according to Caballero and Geltman. The three speakers agreed that uncertainty exists about what the future holds for these populations because of potential policy changes, and that uncertainty affects how and if people in these populations feel safe in seeking health services, making it critical to build trust. Fernandez described a San Francisco Department of Health “You Are Safe” campaign in which posters saying the health care system was safe were put up throughout San Francisco General Hospital and its affiliated clinics and a postcard was sent to every parent who has a child in the San Francisco Unified School District.

![]()

During the discussion, Geltman said that there is federal funding to help establish relationships between small community agencies and local refugee populations, and clinicians and public health practitioners must help establish those relationships. Caballero highlighted the importance of having community board members or patient leadership councils. Perea pointed out the need for civic engagement to ensure that elected officials act based on what is good for the community rather than from self-interest.

Laurie Francis from the Oregon Primary Care Association said the federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) originated as centers of community health with a focus on upstream issues such as equity, education, legal assistance, and other social and economic issues but also provide health care services to those with limited access to health care. Caballero noted that understanding and addressing social needs as well as health care needs are critical to the health of marginalized individuals. Geltman said that the advent of health literacy as an academic field brings to the fore concepts such as patient activation. Teaching people to be engaged and active is a skill, he said, one that has to be learned.

ACCESSING AND USING HEALTH CARE

The second panel of the day featured presentations by Nick Nelson, director of the Highland Hospital Human Rights Clinic; Julia Liou with Asian Health Services; Jesús Quiñones, referral coordinator at Casa de Salud in St. Louis, Missouri; and Kari LaScala, a health communication specialist with Wisconsin Health Literacy.

Nelson opened the panel by presenting what practitioners need to think about when interacting with people who are immigrants, refugees, or migrant workers. A major issue to consider, he said, is that among those born outside the United States there is a relatively high prevalence of torture and other forms of abuse and trauma such as domestic violence, socioeconomic issues, ethnic persecution, and migration trauma. Another major issue is the need to integrate mental health and physical health, he said, because trauma can present with a broad range of symptoms that are rooted in individual idiosyncrasies and in the cultures of the individuals in whom they develop. And then as an internist, he said, the most complicated thing to learn and understand has been the impact of socioeconomic issues. Many primary care clinicians do not have the training or experience to imagine the hardships that immigrants, refugees, and migrant workers have to contend with, Nelson said. He concluded by saying, “I think it is more important now than ever [before] that clinicians—people who are on the front lines who are working with migrants and refugees—cultivate a humble, solicitous, and caring curiosity about these medical, psychiatric, and socioeconomic barriers and complications to care.”

Liou, the second speaker of this panel, spoke of an innovative health care program of the Asian Health Services that is focused on nail salon workers. Nail salons are an $8 billion industry in the United States and the products that nail salon workers handle on a daily basis—6 to 7 days per week, 8 to 10 hours per day—contain known carcinogens and reproductive toxicants, she said. Nationwide there are about 400,000 nail salon workers, 58 percent of whom are of Asian descent, the vast majority are female immigrants who speak limited English, and the yearly income is less than $23,000, Liou said. In addition, many are very distrustful of the government because of their home countries. The Asian Health Services efforts started small, with a gathering of just six people. But today more than 20 organizations throughout California are part of the California Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative. The Collaborative provides materials with realistic tips for protection (e.g., using gloves), it creates approaches to help workers learn English (a desired goal of the workers), and it provides advice for addressing ergonomic health issues such as wrist pain. It has also started a leadership development program and a Healthy Nail Salon program that rewards salons using safer products. And by working with the state legislature the collaborative was able to get a healthy nail salon bill passed. Liou concluded her presentation by saying, “[U]nderlying all of this, collaboration has been very important. We could not have done this on our own.”

The third presenter, Quiñones, spoke about establishing trust with the community and facilitating access to services throughout the health system. He said that when a person enters the Casa de Salud, communication is made easier by the fact that there is no glass partition between the person and the receptionist and also patients are not asked at the front desk for their insurance information or their documentation status. Quiñones described a major effort of the center, the GUIA (Guides for Understanding Information and Access) program, which is a social work, case management program that supports the center’s clinical work. The GUIA program focuses on systems-level access by building relationships with health care organizations to ensure there are referral pathways for center patients. Many of the patients do not qualify for Medicaid so the center staff guide them through the financial assistance processes that the various health care organizations have established. Case managers focus on patient-level advocacy, patient-level access, and referral coordination; guiding patients through the whole process from screening to diagnosis to treatment,

Quiñones said. Lastly, he said, they engage in health education, coordinating a home visit program to address chronic illnesses in the community. “I really want to emphasize” Quiñones said, “that we have been able to establish trust in the community, trust in the health care system by simply guiding [patients] through the process.”

The final presentation of this panel by LaScala focused on Wisconsin Health Literacy’s project Let’s Talk About Medicines: Workshops for Refugees and Immigrants. “The project goal was to help refugees and immigrants gain a better understanding of how to more safely and effectively use their medicine and also develop a comfort level in asking their pharmacists or doctors questions.” LaScala said. They hold 20 workshops per year, partnering with and holding the workshops at trusted community organizations. The greatest challenges, LaScala said, are interpretations at the workshop and translations of written materials. She described several things that need to be kept in mind when working with people born outside the United States. First, they come from diverse backgrounds, not just different cultures but different communities and languages within the cultures. Some have been in refugee camps for a very long time, others are coming as immigrants. The level of education varies widely with some having no formal education who cannot read or write in their own native language. They also have different experiences with medication use, she said. LaScala said that the organizations with which they work have to prioritize what they are able to focus on, especially in the face of the uncertainty about U.S. policies on immigration and refugees. It takes a long time for the organizations to recruit participants for the workshops and conduct the follow-up surveys 60 days later, she added. Important lessons learned, LaScala said, were to keep it simple, that a smile and a hello go a long way to help keep the workshops interactive, and that this work is important. “Some of these people are suffering or come from serious trauma or tough backgrounds,” she said, “but just to have fun in the workshop is a really nice way to go.”

During discussion, Nelson said that his sense of what clinicians need is more and broader education at the medical school level and the residency level about the kinds of issues raised in the panel’s presentations. “I would love to have my residents rotate through all of these programs” described by the panelists, he said. Quiñones said he would like to see more integration of physical health and mental health because of the many patients who experience trauma.

In response to a question about how the increase in immigration enforcement is affecting the clinics with which the panelists are associated, Liou said that the Asian Health Services has had patients who want to get off Medi-Cal (California Medicaid), even if not warranted, because of a high level of anxiety. In response to anxiety about immigration enforcement or immigration officers showing up at clinics, Nelson said, “[W]hat most people are doing right now is developing clear policies about who is allowed where, what is a restricted area and what is not, and training staff in how to respond to legal, semi-legal, or, frankly, illegal incursions by immigration enforcement officials.”

HEALTH LITERACY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OUTREACH

Panelists addressing outreach were Maricel Santos, associate professor of English at San Francisco State University; Justine Kozo, chief of the Office of Border Health for the San Diego Health and Human Services Agency; Rishi Sood, director of policy and immigrant initiatives for the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; and Mimi Kiser, chair of Emory University’s Religion and Health Collaborative Academic Working Group. Santos opened her presentation by saying she had two takeaway messages. First, those in the adult literacy world should be spending more time with public health, and those in public health should be spending more time in the adult literacy world. Second, it is not just about speaking English, it is about “connecting English language education with the world outside.” Translanguaging1 raises the idea that health literacy among immigrant and refugee communities should be addressed as a multimodal, multilingual competence. “We’re not there yet in our research,” she said, “but if you look at what’s going on in the classrooms where people are developing this competence, you do not see it demonstrated in English only.” What it takes to gain a voice as a health literate person in this world, she said, requires opportunities for a person to tell his or her own story and the right to impose listening on others, which is very important for patient engagement. Another important tenant is the opportunity to ask questions, even risky ones, Santos stated. She concluded her presentation by making three points. First, teacher training and health education training need to be interacting with each other and need incentives to do so. Second, there need to be new ways of thinking about health literacy credentialing, a way to communicate to others that you know how to do certain things. Finally, “it’s our job to stop interrupting, whether you come from the academy or you’re a policy maker, stop interrupting the conversation that’s so desperately trying to be heard,” she said.

___________________

1 “Translanguaging is the act performed by bilinguals of accessing different linguistic features or various modes of what are described as autonomous languages, in order to maximize communicative potential. It is an approach to bilingualism that is centered, not on languages as has often been the case, but on the practices of bilinguals that are readily observable in order to make sense of their multilingual worlds” (Garcia, 2014).

Julia Ackley from Sutter Health asked how to go about partnering with adult education programs. Santos replied that there is a lot of information online. For example, she said, the Outreach and Technical Assistance Network (OTAN) has a list of programs that can be searched by zip code. Universities have institutes for civic and community engagement that can help build bridges to the community and most universities have some sort of service learning component that their students complete, Santos said. Such students could provide a cadre of individuals in training who might be able to work in the community.

Kozo spoke about a project using partner community organizations to relay information to limited English proficient populations during public health emergencies and natural disasters. San Diego has about 3 million residents, is 32 percent Latino, and receives about 3,500 refugees per year with more than 100 languages spoken. She said more than 400,000 people living in San Diego speak a language other than English at home and report speaking English less than very well. The area is prone to natural disasters, with fire being one of the big ones. In 2012 eight focus groups were held composed of community-based organizations serving speakers of Arabic, Chinese, Filipino, Karen, Korean, Somali, Spanish, and Vietnamese. The groups were asked questions such as during an emergency, where do you get your information? Who do you turn to, and who do you trust? Do you have a landline at home? What media does your community have access to? If you received some information from the county government, how would you respond? What is your level of trust with the government? What was learned from the focus groups, Kozo said, is that in times of need, people turn to one another for support and information. “Social networks are everything, family and friends,” she said. All eight groups also mentioned schools, the Red Cross, and faith-based organizations as trusted sources. A key finding, she said, was the varying levels of trust in the government. The decision was made, Kozo said, to partner with trusted community-based organizations who will relay the government agency’s updated, accurate, and vetted information. The outreach includes trainings three times per year and a two-way communication platform that shares pertinent public health information in multiple languages and is updated in emergencies. However, Kozo said feedback on the platform has been negative so they are searching for a new platform. Kozo concluded by saying they will continue to do outreach to community-based organizations and to work with their language champions, people who serve as ambassadors to their respective communities.

Sood reported that about two-thirds of the undocumented residents in New York City, or 240,000 adults, are uninsured. To address the health care needs of this population, the city decided to launch a direct-access health care program called Action Health NYC, a program modeled after programs in California and Harris County, Texas. This program has a formal enrollment mechanism tied to other city programs including IDNYC, New York City’s municipal identification program. The key elements of the program, Sood said, are a defined network, a consistent fee scale, a patient membership card (which in New York City is the municipal identification card), predictable costs at the public hospital fee scale, and basic elements of care coordination and customer service. The goal for the first year, Sood said, was to enroll 1 percent of the 240,000 uninsured undocumented adults, or 2,400 people. Outreach focused on three boroughs and a handful of neighborhoods. They partnered with six different community-based organizations in Brooklyn and five in Queens and Manhattan to get the word out. The program placed paid ads in community news media, officials like the health commissioner and the deputy mayor for health and human services spoke at different venues about the program, and targeted mailings were used. More than 2,400 participants speaking 32 languages from 77 countries were enrolled in the first year. Despite this success, while local government is distinguished from the tone of the federal government, it is still the subject of mistrust and needs to partner with trusted local groups, and although Action Health NYC took “every precaution to protect our participants’ information, for some people that was just too much, and they said no, I’d rather not,” said Sood.

In response to a question about incorporating mental health into the efforts described, Sood said the program he discussed covers what is covered at the public hospitals and FQHCs. Another initiative called Thrive NYC focuses on improving the mental health of all New Yorkers. Oral health services are also covered.

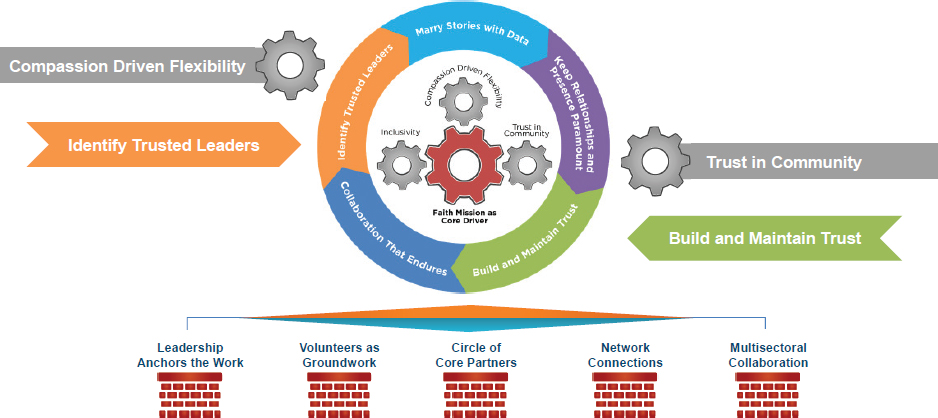

Kiser spoke about faith-based organizations as partners and their role in establishing trust with vulnerable populations. Faith-based networks were mobilized in 10 sites around the country to reach vulnerable populations with H1N1 prevention services, education, and vaccines. Based on the work of this project, Kiser said they were able to identify a model practices framework (see Figure 1).

“Most communities have leaders and organizations with relationships and the kinds of commitments to serve in the public sphere that can leverage connections and social capital resources for the well-being of the community,” Kiser said. She concluded by saying that she was concerned about the levels of mistrust in government and health care providers. “It’s very rewarding to see what these community networks and leaders have been able to build over time in their communities,” she said.

SOURCES: Emory Interfaith Health Program as presented by Mimi Kiser at Health Communication with Immigrants, Refugees, and Migrant Workers: A Workshop on March 15, 2017.

APPLICATION OF HEALTH LITERACY TO COMMUNICATION WITH IMMIGRANTS, REFUGEES, AND MIGRANTS

Megan Rooney, director of program development at Health Literacy Media, presented some practical health literacy strategies to address the unique mental health challenges and experiences of trauma and stress, with a focus on helping individuals build a sense of trust and a sense of control in their lives. Rooney explained that in the United States today there are about 43 million immigrants (13 percent of the population), 3 million refugees, and 3 million migrant workers. Strategies for action include engaging in cross-cultural communication that involves an awareness and acceptance of cultural differences; self-awareness; knowledge of the client’s culture; and adaptation of skills to meet the unique needs of individuals from these groups. Culturally informed organizations offer regular training on cultural humility and awareness, they work to ensure the workforce reflects the client population, and they have translation and interpreting services available, Rooney said. They also offer services adapted to the specific needs of the client population and evaluate treatment outcomes by racial, ethnic, and language groups to measure whether strategies are improving outcomes, she added. Rooney highlighted five strategies of trauma-informed care: provide a safe environment, build a trusting relationship, emphasize and encourage client choice and control in treatment, take a person-centered approach to care, and help clients understand how their past experiences may be contributing to their current circumstances or reactions (i.e., empowerment). Other strategies to improve health literacy, she said, include using plain language and teach back and building client–provider relationships. She concluded by saying follow the client’s lead. Every culture has its own practices; for example, some shake hands, others do not. What has been discussed will lead to a better, empathic, trusting relationship between a provider and a patient, she said.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Panelists for the moderated discussion included Anthony Iton, senior vice president for healthy communities of The California Endowment; Clifford Coleman, assistant professor of family medicine at the Oregon Health & Science University; Iyanrick John, senior policy strategist for the Asian and Pacific Islander American Health Forum; and Hugo Morales, executive director and co-founder of Radio Bilingüe. The moderator for the panel was Suzanne Bakken, Alumni Professor of Nursing and Professor of Biomedical Informatics at Columbia University. Bakken opened the discussion by asking what health practitioners and health care practitioners need to know about working with these populations. Coleman replied that there is no quick answer but the first task is raising awareness across all health care professions of

the real potential to improve lives through making changes in communication, building trust, and engaging with communities. There also needs to be a better matching of information to skills, he said, not just for the populations being discussed today, but across the health care system with all populations. John highlighted the importance of building relationships and partnering with trusted community-based organizations, including providing financial support.

Bakken then asked what systemic changes are needed. Iton said The California Endowment initiative, Building Healthy Communities, will be spending about $1 billion over 10 years in 14 California communities, none of which will be spent on health care. “Communities basically have a pretty good sense of what they need to be healthy. They need the health care system and the education system and the criminal justice system and the land use system to essentially cooperate in facilitating their access to those health protective resources,” Iton said. We need to build trust, personal-level agency, and community-level agency, allowing people to tell their stories of how they got to where they are, he said. Morales said immigrants need to build their own institutions and a positive culture of health within their communities and we need to support traditional arts and immigrant native languages and multilingualism in schools. We also need to support authentic community media; build the capacity to address integration through local and regional collaboratives of service providers, immigrant advocates, and legal services; and build effective channels of input and feedback on those services, Morales said. He concluded by saying that when looking for community leaders we should keep in mind, that “even though their formal education may be very low and they may be illiterate, they may also be the most trusted person or leader in their community.” Coleman said Oregon Health & Science University is attempting to change the system from the learner on up by teaching four core habits: building a relationship (e.g., by sitting down, speaking slowly, making eye contact that matches that of the person); agenda setting (figuring out what is the person’s main concern); using plain language; and checking for understanding.

The final question that Bakken put to the panel was who needs to be involved to make the changes discussed here? Iton said, “If you want to change the outcome, you’ve got to change the power dynamic.” He went on to say, “Where institutions don’t behave in a way that actually supports a community’s health, we create the power of that community to challenge that institution and to hold it accountable.” Morales said one needs to include the client base, in this case, immigrants, refugees, and migrants. John said he thinks health economists need to be involved to help figure out the benefits and cost savings. Coleman said incentives are important, for example, The Joint Commission could provide incentives to health care institutions and certifying organizations could provide incentives to health professional schools.

CLOSING REMARKS

Rosof concluded the workshop with a discussion of organizational professionalism as described in an article published in the online version of Academic Medicine. What was heard today, he said, aligns with the responsibility of academic and health care institutions to the communities they serve.♦♦♦

REFERENCE

Garcia, O. 2014. Education, Multilingualism and Translanguaging in the 21st Century. In Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education, edited by O. Garcia and L. Wei. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave McMillan UK. https://ofeliagarciadotorg.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/education-multilingualism-translanguaging-21st-century.pdf (accessed March 28, 2017).

DISCLAIMER: This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Lyla M. Hernandez as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the rapporteur or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. The responsibility for the published Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief rests with the rapporteur and the institution.

REVIEWERS: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Ruth Parker, Emory University School of Medicine, and Rima Rudd, Harvard School of Public Health. Lauren Shern, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS: This workshop was partially supported by AbbVie Inc.; the Aetna Foundation; the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HHSP23337024); American Dental Association; Bristol-Myers Squibb; East Bay Community Foundation (Kaiser Permanente); Eli Lilly and Company; Health Literacy Missouri; Health Literacy Partners; Health Resources and Services Administration (HHSH25034011T); Humana; Institute for Healthcare Advancement; Merck & Co., Inc.; National Institutes of Health (HHSN26300054); National Library of Medicine; Northwell Health; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (HHSP23337043); and UnitedHealth Group.

For additional information regarding the meeting, visit nationalacademies.org/healthliteracyRT.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. Health communication with immigrants, refugees, and migrant workers: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/24796.

Health and Medicine Division

Copyright 2017 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.