Proceedings of a Workshop

| IN BRIEF | |

|

June 2017 |

Protecting the Health and Well-Being of Communities in a Changing Climate

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

On March 13, 2017, the Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, and Medicine and the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement held a 1-day public workshop at the National Academy of Sciences building in Washington, DC. The workshop featured presentations and discussion about regional, state, and local efforts to mitigate and adapt to health challenges arising from climate change, ranging from heat to rising water.1

Workshop participants were welcomed by Lynn Goldman, dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University and vice-chair of the Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, and Medicine, and George Isham, senior advisor, HealthPartners; senior fellow, HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research; and co-chair of the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, also welcomed the audience and provided an overview of a climate and health meeting held in February 2017 at The Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia, with The Climate Reality Project and other partners. Benjamin quoted the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “fierce urgency of now” to reflect on the time-line for responding to climate change as a public health issue. Benjamin briefly outlined the health effects of climate change and some of the preparation and responses needed. When asked how the case for addressing climate change could be made to policy makers and the public, Benjamin gave an example. Benjamin described his response to the concern sometimes expressed that climate change regulations may dampen employment opportunities by stating that if people’s lives or health are threatened by the effects of climate change, they cannot work. Moreover, he added, the growth in green jobs further undermines the jobs argument against addressing climate change.

SETTING THE STAGE

Jonathan Patz, director of the Global Health Institute, John P. Holton Chair in Health and the Environment, and appointee to the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, all at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, described his talk’s focus as climate change challenges presenting an opportunity for health. Patz shared maps from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change showing a range of scenarios for global warming over the remainder of the century. Patz then discussed several key challenges posed by the changing climate, including hydrologic extremes (droughts, floods, and sea level rise), threats to food and water supplies, mental health effects, and environmental refugees due to forced population movement (e.g., retreat from coastal settlements). Climate modeling for the New York City (NYC) region indicates a tripling in 90 degree plus days from 13 to 39 per year. Heat is a challenge for multiple reasons, including effects on (1) vulnerable groups such as older adults; (2) plants (damaging crops, also threatened by drought, and boosting plants such as ragweed, that produce harmful pollen);2 and (3) disease vectors, especially mosquitoes that carry dengue, Zika, West Nile viruses, and other pathogens.

Patz discussed the global context for U.S. decision making about climate change. He outlined the evidence indicating that climate change poses a national security threat. For example, although the unprecedented Syrian drought

___________________

1 The workshop was intended to (1) provide an overview of the health implications of climate change, (2) explore mitigation/prevention and adaptation/resilience-building strategies deployed across the county, and (3) discuss aspects of collaboration on climate and health issues, all in the context of a range of considerations and limitations, including wide-ranging regional differences.

2 See, for example, Ziska et al. (2011).

![]()

cannot be said to have caused the current civil war, it is clear that the drought caused significant instability by spurring migration from rural to urban locations in Syria and by creating severe food shortages. The United States continues to emit “six times the global average CO2 per person,” stated Patz, and the worldwide effects are first being observed in areas already experiencing the most climate sensitive health conditions such as malaria, malnutrition, and diarrheal diseases.

The health frame for discussing climate change is critical because that is where immediate and substantial actions are needed, said Patz. Policy on energy, food systems, transportation, and urban planning is public health policy because of the intertwined nature of the factors that shape people’s health and well-being. Patz cited a Massachusetts Institute of Technology study that showed the potential co-benefits that could be realized from building a cleaner energy society, including reductions in PM2.5 (a measure of fine particulate matter air pollutant), and that could have substantial health benefits (Garcia-Menendez et al., 2015). Urban planning and transportation shape climate and health; thus, the way cities are endeavoring to design physical activity back into human lives (rather than simply facilitating motor vehicle movement) could change not only air quality, but also troubling upward global trends in body mass index and obesity highlighted in a recent study (NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, 2016).

During the discussion period moderated by Henry Anderson of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, a participant asked how to move forward in a political context that does not seem influenced by the evidence about climate change. Patz responded that credible spokespersons (e.g., nurses, physicians) and novel alliances are needed. These are necessary to provide the support of the public health community to the most disadvantaged groups, including coal miners, to ensure that no one is left behind as the economy shifts toward renewable sources of energy.

Isham asked what those who are not experts on the environment could do to understand the issues. Patz replied that becoming expert listeners is crucial, listening to the languages of other sectors, and also engaging in a systems approach, one that brings together the right expertise and engagement in a cross-disciplinary manner.

Maureen Lichtvelt of Tulane University stated that she believed the highest priority emerging from the workshop is that all participants increase their environmental health literacy, no matter where they live. She also added that one need not go to Syria to witness environmental refugees—they may be found in places as close to home as Louisiana’s bayous.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE SOUTH

Linda Rudolph, director of the Center for Climate Change & Health at the Public Health Institute, welcomed the panel of four speakers. Maria Koetter, director of the Louisville Metro Office of Sustainability, described the areas of focus in the city’s comprehensive sustainability plan, the interconnected issues of energy efficiency, tree canopy and reforestation, green infrastructure, and urban heat management. In 2012, Brian Stone of the Georgia Institute of Technology released a study that “showed that Louisville had the most rapidly warming heat island in the country.” The city applied and received a grant from Partners for Places to hire Stone to do an in-depth analysis of Louisville’s urban heat island issues and help the city model strategies and scenarios to help manage the heat, including assessing population vulnerability and heat mortality data (Urban Climate Lab, 2016). Koetter shared Louisville maps showing how the areas with the highest heat are also the areas that experience other layers of disadvantage and poor health outcomes such as hypertension. The city has taken steps to implement multiple strategies to green, cool, and conserve, including providing incentives to businesses to opt for cool roofs (e.g., EnergyStar roof tiles) when replacing existing ones, demonstrating green practices in city-owned structures and spaces, and piloting a green vegetative buffer at a carefully selected location—an elementary school located near a roadway with heavy air pollution—to show the effects on health. The green vegetative buffer involved planting 100 trees between the school and the road. The city partnered with the University of Louisville, which conducted air monitoring and biomarker sampling before and after the buffer was installed. Findings, which will be published in the future, showed 60 percent reduction in ultrafine particulates.

Halida Hatic, director of community relations and development at the Center for Interfaith Relations in Louisville, Kentucky, presented with Rachel Holmes, program coordinator of The Nature Conservancy’s Healthy Trees, Healthy Cities urban forestry initiative. They talked about the Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces that the two organizations developed in collaboration with GreenFaith and with the Louisville Islamic Center/River Road Mosque, Christ Church Episcopal Cathedral, and St. Xavier Catholic High School. Through the course of focus group engagement over a period of 6 months, the organizers sought to identify the needs of the communities of faith in the intertwined areas of spiritual, environmental, and individual health, and they followed five guiding principles throughout: (1) no cost to participate in the audit process, (2) simple equipment (e.g., paper and pen, camera, tape measure) and protocols, (3) well-supported trainings and methods, (4) opportunities for differently abled individuals, and (5) community connectivity. The audit has four components: (1) tree canopy assessment (which includes a field assessment of tree health); (2) Web-based landscape mapping through the Habitat Network; (3) grounds management evaluation; and (4) worship/community assessment (which includes administering a basic questionnaire asking about liturgical practices and the integration of the concepts of “nature” and “stewardship” within community activities).

Lisa Abbott, an organizer at the 35-year-old grassroots organization Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, described how the Empower Kentucky project emerged in 2015 in the wake of bipartisan Kentucky political opposition to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Clean Power Plan. Both Republican and Democratic candidates for governor opposed the EPA rule. Empower Kentucky aimed to develop through a public process a “people’s energy plan” for Kentucky and held a series of facilitated conversations at six locations throughout the commonwealth, engaging 750 people. Participants were asked to share personal stories about their relationship to the energy system, such as family members who had worked in the coal mines. The Empower Kentucky “people’s energy plan” (published April 2017)3 contains four chapters and sets of recommendations that focus on energy efficiency and renewable energy, on job creation and a just transition for workers affected by the shift in energy sources, on health and equity, and on lowering utility costs for lower-income households. The plan also includes a holistic look at multiple issues intertwined with climate and energy production, such as food systems, tree canopy, and transportation. Addressing jobs, health, bills, and climate in an integrated way will be used to educate, communicate, engage, and share relevant data and information with current and emerging decision makers, according to Abbott.

During the discussion period, Natasha DeJarnett of the American Public Health Association asked how the speakers facilitate public–private partnerships. Hatic stated that it is crucial to leave one’s own agenda at the door in order to engage in an authentic conversation and gain buy-in. John Bolduc from the City of Cambridge Community Development Department asked how businesses are responding to the efforts being undertaken in Louisville. Hatic stated that major employers in Louisville participate in the city’s Sustainability Council, of which she and Koetter are members. Koetter added that the engagement of big business is not a surprise, but smaller businesses have been less receptive. However, the city’s approach may be helpful in its emphasis on voluntary action and incentives. Hatic concluded by underscoring the centrality of relationships in recognizing “the mutual need and the shared values through [interactions among] nongovernmental organizations, governmental organizations, and corporate America.”

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE MIDWEST

Surili Patel, senior program manager in environmental health at the American Public Health Association, introduced the next two speakers. Paul Biedrzycki, director of disease control in environmental health with the City of Milwaukee Health Department, shared information about the nation’s local health departments broadly—highlights from the National Association of County & City Health Officials’ (NACCHO’s) 2014 Are We Ready? Report 2: Preparing for the Public Health Challenges of Climate Change—and about his own agency’s work to address the health challenges resulting from climate change (NACCHO, 2014). Biedrzycki shared a few key findings from the NACCHO report, including that 8 out of 10 local health directors recognize that climate change is occurring (regardless of cause), and less than 5 percent of local health departments have adequate capacity or capabilities to plan for the effects of climate change. Biedrzycki added that the fiscal environment for public health practice makes it necessary to partner with others and to work in cost-effective ways. He outlined four examples of work Milwaukee is doing to address effects of climate change. These are (1) a project that combines rainfall harvesting, food security, and addressing water pollution through community gardens that support a homeless shelter population and local markets and restaurants in the city’s low socioeconomic area on the north side; (2) efforts to address the increasing prevalence of Lyme disease in areas of the country, likely associated with the shifting ecosystems of its vector populations, white-footed mice and deer; (3) engaging businesses on the topic of continuity of business operations in the event of severe weather, such as a power outage due to extreme heat, or of a serious communicable disease outbreak affecting the workforce; and (4) the heat vulnerability index, which the city of Milwaukee pioneered before most other health departments working on climate issues. The index is a composite of 20 variables that shows the overlapping layers of disadvantage or vulnerability that place some communities at far greater risk of poor health outcomes related to climate change. Work on the index was supported by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) grant.

Biedrzycki concluded with the suggestion that making the economic argument can be compelling and convincing to policy makers and so can clearly delineating the nexus between climate change and items that top the priority list for most mayors, county executives, or other local leaders, such as job creation, early education, and public safety. He added that it is crucial to leverage existing community networks and resources—in some cases, the climate change planning work may take place within economic sustainability or emergency preparedness programs, in addition to environmental health or communicable disease units.

Jeffrey Thompson, executive advisor and chief executive officer emeritus at Gundersen Health System (GHS), shared highlights from the work of his health system. GHS made explicit the link between the health of its patients and air pollutants. Because hospitals and health care constitute approximately 20 percent of the economy and are intensive consumers of energy, they have a huge impact on the environment and a large carbon footprint (see Table 1). Health and rising energy

___________________

3 See http://www.empowerkentucky.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Empower-Exec-Summary-Report-final-1.pdf (accessed June 1, 2017).

costs, Thompson pointed out, made the business case to move in a more sustainable direction. Climate change, Thompson stated, “wasn’t the discussion. The discussion was how are we going to decrease pollution that’s hurting people, how are we going to use that system to decrease our operating cost and instead of sending money outside the state, $15 billion leaves Wisconsin, how are we going to keep that in the state?” One inspiration for the GHS journey was found in the book Natural Capitalism, which urges ignoring the conventional wisdom that pits jobs against the environment (Lovins et al. 1999). The book, Thompson added, reminds the reader that there is no “away” to which pollutants may be removed. GHS’s board agreed that the proposal aligned with its mission, and the system’s leaders first turned to finding partners, including others in the business community. The return on GHS’s investment has been clear: $2 million spent on conservation in the first 2 years, with $1.2 million in savings every subsequent year.

GHS set a goal in 2008 to become powered by 100 percent renewable energy by 2014 through a range of strategies, including conservation and generating electricity, stated Thompson. One source of renewable energy is from a biogas project with the local county and its landfill, which heats, powers, and cools an entire GHS campus and achieves other benefits: it is a source of revenue for the county ($250,000), offers health benefits from lessened reliance on air polluting fossil fuels, and it is environmentally sound because it displaces other energy sources and also prevents the landfill gas being released into the atmosphere. Another source of fuel is a dairy biogas project that has multiple benefits, including the capture of methane gas. Thompson said that in 2016 GHS achieved 90 days of energy independence and, more importantly, the health system’s greenhouse gas emissions have decreased more than 90 percent. In addition to the benefits previously outlined, concluded Thompson, there is a strong sense of pride among staff, and GHS is hiring people because of its sustainability programming that appeals to recent college graduates. Thompson concluded his presentation by reminding the audience that the “pitch” that launched GHS on its journey to sustainability was not about addressing climate change, but about health and economics—both crucial to the mission of the health system.

Rudolph asked how Thompson would reconcile the health and economics message with the climate change message, and he replied that he focused on the overlap between his values and his board’s values. Thompson said that although he knows that “the health effects of climate change are devastating, and that there is better evidence for climate change [being] caused by people than there [is] for most of the medical treatments in this country,” that was not the framing that was going to be effective. He framed the argument in a manner that allowed all parties to work together and achieve the shared goals of improving health and the bottom line. Biedrzycki asserted that at the state level the linkages between the changing climate and workforce development, job creation, education, or public safety may not be made sufficiently, and more leadership is needed to help health departments and their partners do the work of connecting the dots.

David Kindig of the University of Wisconsin–Madison asked Thompson about the state of acceptance among businesses of the GHS idea. Thompson replied that a few years ago when he helped launch the Healthier Hospitals Initiative, there were only a dozen organizations that signed on to report how they were doing on key metrics related to energy, conservation, or waste management, and today there are 1,400 hospitals or health systems reporting.

Biedrzycki stated that the current national dialogue would ideally move in the direction of asking, “What does success look like from a climate healthy business economy, and how does that intersect with national security and global economic goals and interests of this country?”

Sanne Magnan, adjunct assistant professor, University of Minnesota, asked Biedrzycki if he could comment on the issue of building trust in the context of decreased community cohesion and increased social instability. Biedrzycki responded that walking the talk and delivering on promises made in a timely manner is crucial.

| Emissionsa,b,c,d,e (lbs.) | 2008 | 2016 | % Reduction |

| Carbon Dioxide | 72,386,372 | 1,626,831 | (98%) |

| Particulate Matter | 434,928 | 11,172 | (97%) |

| Mercury | 2.39 | 0.16 | (94%) |

2016 asthma attacks avoided: 9.3f

TABLE 1 Gundersen Health System’s Fossil Fuel Emissions, 2008 and 2016.

NOTES: The 2016 CO2 value is the net sum after adjusting the facility utility energy consumption with the clean energy produced by Gundersen Health System renewable energy projects. a US EPA AP-42. b Practice Greenhealth’s Energy Impact Calculator Data Sources: http://www.eichealth.org/calctest2.asp# (accessed June 1, 2017). c U.S. EPA eGRID Version 1.0 Year 2007 Summary Tables: http://www.epa.gov/egrid (accessed June 1, 2017). d U.S. EPA eGRID 10th edition Version 1.0 year 2012 Summary Tables: http://www.epa.gov/egrid (accessed June 1, 2017). e Air pollution from electricity-generating large combustion plants (PDF), Copenhagen: European Environment Agency (EEA), 2008, ISBN 978-92-9167-355-1. f European Environment Agency. 2008. Air pollution from electricity-generating large combustion plants, https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/technical_report_2008_4 (accessed June 7, 2017).

SOURCE: Jeff Thompson presentation, March 13, 2017.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE NORTHEAST

Biedrzycki introduced the panelists who would share the experience of three northeastern communities. Celia Quinn, director of health care system readiness for the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, gave remarks about the lessons NYC learned from responding to Hurricane Sandy and the ways in which it is integrating the learnings into its resiliency and preparedness efforts. Quinn referenced the availability of useful resources including the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Center for Health Security community checklist for health sector resilience in natural disaster. Quinn briefly outlined NYC’s health system vulnerability to rising water in flood zones, including a total of 67 facilities (11 of them hospitals) and 15,289 licensed beds. Hurricane Sandy led to the evacuation of 37 health care facilities and more than 6,451 people (exact numbers are unknown, but likely higher because of discharges or transfers in advance of the storm). Additional effects of the storm, Quinn added, included power outages, transportation disruption, travel bans, and a lack of access to fuel. During and after the storm there was both a reduced capacity in the health care system and a surge in demand for some types of services (e.g., dialysis and medication refills). Quinn summarized a few lessons. First, the health care delivery system is interdependent in ways that are cast in sharp focus by a natural disaster. For example, lack of plans or resources in ambulatory settings will considerably affect hospitals. Second, the decision to evacuate, Quinn noted, is complex, with life or death consequences, and likely to be scrutinized for multiple reasons and criticized in the case of poor outcomes. Third, the health care system needs surge spaces of different types to respond appropriately to all types of patients. Last, planning for coastal storms and other natural disasters will likely present both immediate and long-term disruptions to health care services. Quinn concluded her remarks by noting that institutional vulnerabilities are quickly revealed in a disaster and can have considerable and severe ramifications for patients. In the face of growing unpredictability in severe weather patterns, health care delivery systems must become more resilient and focus on equity and quality, infection control and communication, and attention to non-health factors that are routinely important and critically important in a natural disaster, such as housing and access to city services. Resilient health care delivery systems can handle surges in patient load whether they are due to a heat wave or to a severe peak in seasonal flu.

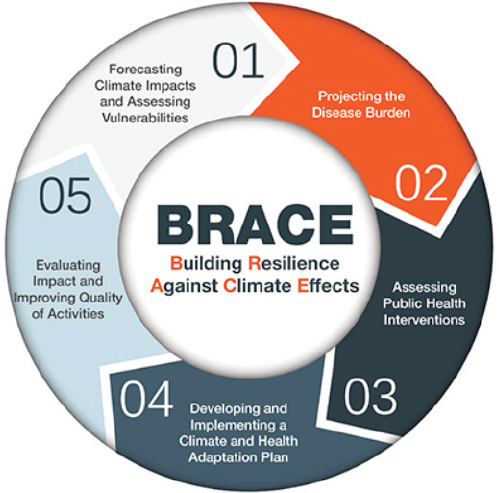

Matt Cahillane, program manager with the Bureau of Public Health Protection, Division of Public Health Services, New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, described the climate context for his work: the northeast U.S. climate is getting warmer, wetter, with more extreme weather events, and this has a number of effects on the environment and population health. The state’s CDC BRACE funding has been used to support several projects around the state, including on Lyme disease and habitat change, heat stress and older adults, storms and resilience, and more clearly understanding weather-related injuries. The communities involved have been using the BRACE framework (see Figure 1) to structure their work. In Step 1 local agencies assess population vulnerabilities and hazards, in Step 2 they estimate how these two factors will affect public health, and in Step 3 of the framework communities can use the CDC Guide to Community Preventive Services4 and other sources to find evidence-based interventions for responding to climate change–related health effects.

The state’s strategic plan for climate and health, Cahillane noted, has three components: (1) building workforce capacity; (2) conducting education and outreach; and (3) informing policies. As one example of informing policy, a health department can examine changes in a community’s tick habitat and also review insect repellent policies of child care centers and schools. If schools and child care centers choose to put in place an opt-in policy, then parents must sign off on the use of repellents known to be safe. This is not an effective tactic to address the threats of tick and mosquito-borne illness. An opt-out policy is better population protection, as it requires the parents to sign off if they do not want the school to use effective repellents. As an example of education and outreach efforts, health departments could work with youth outdoor recreation programs to implement tick-borne disease prevention efforts via training on risk factors for vector-borne disease.

SOURCES: Presentation of Matt Cahillane, March 13, 2017; CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/brace.htm (accessed April 28, 2017).

___________________

4 The Guide is developed by the Community Preventive Services Task Force, see https://www.thecommunityguide.org/ (accessed June 8, 2017).

Kristin Baja, climate and resilience planner with the Office of Sustainability in Baltimore City, Maryland, began her presentation by asserting that talking about climate change with an equity lens requires acknowledging her own privilege and Baltimore’s history of racial segregation and continuing inequities. Interacting with community members requires openness and a willingness to truly listen to people sharing how they have been affected by the displacement and segregation visibly inscribed on the Baltimore map: the black butterfly and the white “L,” the latter being the area where much of the transportation system is located and the Inner Harbor area.

Baltimore, Baja explained, is threatened by water from all sides, given its location at the top of Chesapeake Bay and at the base of four watersheds. The city includes climate change planning in the federal government’s all-hazards mitigation plan. Depending on the audience, Baja will refer to the problem at hand as either disaster preparedness (business and residents) or as resilience (organizational partners). Applying an equity lens in Baltimore’s climate resilience planning means “prioritizing neighborhoods that have the highest vulnerability and also the historic disinvestment.” The city’s Office of Sustainability engages communities by asking residents in meetings held in their neighborhood what they are going to do and how they plan to be part of the work of resilience planning, including conducting asset mapping to identify what is available and missing in each neighborhood. One tactic is to build emergency kits together with community members. Another tactic is to distribute window cards for residents to post with “help” on one side and “safe” on the other, in cases where a household has what it needs to survive the emergency.

A major gap in Baltimore’s resilience planning is that many residents do not have transportation or opportunities to evacuate in an emergency, and they also lack (and do not have the ability to stockpile) extra food and water and a safe place to get trusted information. The city has been working with residents to establish resilience hubs in the black butterfly area of the map—trusted neighborhood sites such as churches—where the city can provide backup food, water, and information. The Office of Sustainability is working with the city’s health department to make the hubs public health service delivery sites as well. Baja also described the Ambassador Program implemented by the city, which has trained and deployed 150 community ambassadors who conduct outreach and prepare materials for their neighbors and play a key role in facilitating the exchange of information about resiliency between the residents and the city, including the Every Story Counts activity that showcases local examples of individual resilience. Ambassadors convey the needs and ideas of residents to planners, and planners, in turn, use that input and communicate back to communities about how that input shaped the city’s planning.

During the discussion period, Quinn responded to a question about cross-sector communication and collaboration by noting that NYC has about 23 independent coalitions that come together as the NYC Health Care Coalition, which can serve as a vehicle for executing planning, joint training, and exercising together. In response to a question about funding, speakers listed sources of federal, state, and local support, as well as substantial philanthropic support (such as in Baltimore) and in-kind resources, such as resident time and commitment. One topic raised in the discussion was disaster fatigue, acknowledged as a possibility by Quinn, who said the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene incident comment system was activated for 768 days straight, and by Biedrzycki, who noted that New Hampshire is working with the National Weather Service to determine how to alert people to the threat posed by moderate heat days that can have the same effect as the highest heat days. Ray Baxter, health policy advisor, asked how the work all panelists are doing can be scaled and to what extent are they themselves scaling work pioneered by others. Baja responded that sharing important reports and articles can cross-pollinate across sectors (e.g., resilience and public health). She added that scaling up or at least spreading can take place across similar regions. For example, Milwaukee and Baltimore share a history of segregation and experience similar challenges related to trust and equity, providing an opportunity to learn from each other.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WEST

Goldman moderated the day’s final panel. Kathy Gerwig, vice president for employee safety, health, and wellness and environmental stewardship officer at Kaiser Permanente, situated the health system’s climate action in its environmental stewardship work, which is a part of its community benefit efforts (the complete list of Kaiser Permanente environmental stewardship goals shared by Gerwig5 includes climate action, sustainable food, and waste reduction). Health care organizations, stated Gerwig, play multiple roles relevant to climate, many of which were mentioned previously: they are emitters of greenhouse gases and big water users and waste generators. Hospitals and health systems are often also the largest employer in town, huge purchasers with large supply chains that may be global or local (with implications for climate change), and significant landowners. The community health needs assessments mandated by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act for nonprofit hospitals and health systems serve as an “opportunity because they increase accountability and transparency for how not-for profit hospitals spend their resources,” and climate is beginning to surface as a community need in these assessments.

___________________

5 See https://share.kaiserpermanente.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/EnvStewGoals2025_FINAL2.pdf (accessed June 1, 2017).

Gerwig described the many connections between climate and other determinants of health: poor air quality days mean lessened opportunity for outdoor physical activity, including reduced physical education in public schools. Lack of local jobs means longer commutes, poorer air quality, and less economic security. Gerwig acknowledged that Kaiser Permanente benefits from its California headquarters location for several reasons, including the fact that 25 percent of California’s energy supply comes from renewables. She recommended “[a]sking your health care partners to publicly report their greenhouse gas emissions, to require LEED6 certification and to ask suppliers to use local employees” in order to achieve climate co-benefits.

Renata Brillinger with the California Climate & Agriculture Network began by noting that 7 percent of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions occur in the form of on-farm emissions. Other challenges include groundwater contamination from the use of nitrogen fertilizer, soil salinization, and water scarcity, as well as declining farmland. The California cap-and-trade program serves as a key economic incentive and funding source to drive down greenhouse gas emissions. Brillinger outlined four state agriculture programs that can play a significant role in addressing climate change. These include the Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation (SALC) Program, State Water Efficiency and Enhancement Program, Dairy Methane Reduction Program, and Healthy Soils Initiative. State funding for these four “smart agriculture” programs has grown from $27 million (2014–2015 total) to $70 million (2015–2016) to $92.5 million (including SALC; 2016–2017).7

Fletcher Wilkinson, the climate change program coordinator at the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals (ITEP) at Northern Arizona University, began by recognizing that there are a wide range of tribal climate change issues as varied as the geographic locations and cultures represented. ITEP works with tribes on environmental issues. Its climate change program was started in 2009 with an EPA grant and it has since been solely grant funded and aims to be a one-stop resource for the tribes working on climate change issues. ITEP works with the tribes in a variety of ways, including building capacity through training workshops on topics ranging from “building buy-in and trust from their tribe to work on these issues” to “developing a vulnerability assessment and eventually writing their own adaptation plan”; hosting a website with information that provides a range of resources, including profiles of other tribes and other adaptation plans; providing a toolkit that is a set of documents tribes can use for every aspect of the planning process; and providing technical assistance.

Wilkinson described several key issues to note when working on climate change planning with tribes. First, tribal culture, which includes traditional foods, food sharing, and ritually important plants such as sagebrush, is itself at risk when those resources are threatened by climate change. Second, traditional ecologic knowledge is a key consideration in adaptation planning. Finally, geographic places are inextricably linked with tribal culture and social cohesion across generations. When climate threats force tribes to consider moving, relocation is an emotionally, as well as socially and logistically complex, undertaking.

CLOSING REMARKS AND REFLECTIONS FROM THE DAY

In his summary comments, Baxter stated that the day’s presentations and discussions repeatedly underscored the fact that the health effects of climate change are real, they are here now, they are unfair and inequitable, and most important, they are preventable. He acknowledged that it will be important to achieve a balance in prioritizing prevention and mitigation versus response and resilience. He described the main gaps he identified in topics covered: no one mentioned fire, a significant issue in many regions, and only a few speakers talked about the emissions and practices of their own institutions or about the need for more expansive preventive interventions (i.e., policy, programs), such as reducing vehicular traffic and increasing mass transit. However, Baxter added, the presentations covered a lot of ground, featuring models of comprehensive planning (e.g., Baltimore, New Hampshire, NYC) that can be scaled and spread, and inspiring local examples (e.g., Louisville, Milwaukee) that may be useful to peer communities. A message of the workshop, Baxter noted, is that “the health effects of climate change and climate change itself can be addressed” and one solution Patz described, Baxter said, is to “reduce carbon, create a healthier environment immediately, whether you believe in climate change or not. Doing the most important things for health and for the principal causes of ill health and reduced functionality will help the environment.” “We also heard,” Baxter added, “that the politics of all of this are not impossible,” but it will be important not only to spread and scale local- and state-level solutions but to complement them with policy change at the national and global level.♦♦♦

___________________

6 LEED, which stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design.

7 Brillinger provided the figure of $85 million during the workshop and later provided an updated figure of $92.5 million resulting from subsequent budget agreement(s) (R. Brillinger, personal communication, May 12, 2017).

REFERENCES

Garcia-Menendez, F., R. K. Saari, E. Monier, and N. E. Selin. 2015. U.S. air quality and health benefits from avoided climate change under greenhouse gas mitigation. Environmental Science & Technology 49(13):7580–7588. https://globalchange.mit.edu/publication/16270 (accessed April 27, 2017).

Lovins, A., H. Lovins, and P. Hawken. 1999. Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

NACCHO (National Association of County & City Health Officials). 2014. Are we ready? Report 2: Preparing for the public health challenges of climate change.eweb.naccho.org/prd/?na609PDF (accessed May 24, 2017).

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. 2016. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: A pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants.http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(16)30054-X.pdf (accessed April 24, 2017).

Urban Climate Lab, Georgia Institute of Technology. 2016. Louisville Urban Heat Management Study.https://louisvilleky.gov/sites/default/files/advanced_planning/louisville_heat_mgt_revision_final_prelim.pdf (accessed April 28, 2017).

Ziska, L., K. Knowlton, C. Rogers, D. Dalan, N. Tierney, M. Elder, W. Filley, J. Shropshire, L. B. Ford, C. Hedberg, P. Fleetwood, K. T. Hovanky, T. Kavanaugh, G. Fulford, R. F. Vrtis, J. A. Patz, J. Portnoy, F. Coates, L. Bielory, and D. Frenz. 2011. Recent warming by latitude associated with increased length of ragweed pollen season in central North America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108:4248–4251.

DISCLAIMER: This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Alina Baciu and Kathleen Stratton as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the rapporteurs or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. The responsibility for the published Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief rests with the rapporteurs and the institution.

REVIEWERS: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Natasha DeJarnett, American Public Health Association, and Mary Pittman, Public Health Institute. Lauren Shern, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS: This workshop was partially supported by the Aetna Foundation, The California Endowment (#10002009), Fannie E. Rippel Foundation, Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS-10002817), New York State Health Foundation (#10001272), and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (#10001270).

For additional information regarding the meeting, visit http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/PublicHealth/PopulationHealthImprovementRT/2017-MAR-13.aspx.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. Protecting the health and well-being of communities in a changing climate: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/24797.

Health and Medicine Division

Copyright 2017 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.