3

Approaches to Health-Literate Medication Instructions

The workshop’s second panel featured three presentations on the current landscape of research on written communication and human-centered design. William Shrank, chief medical officer of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Health Plan, discussed research on written communications. Irene Chan, deputy director in the Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), then spoke about designing labels and labeling for patients, and Edmond Israelski, technical advisor on human factors and retired director of human factors at AbbVie Inc., addressed the use of best practice human-centered design methods in the design of medication materials. An open discussion moderated by Bernard Rosof followed the three presentations.

AN OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON WRITTEN COMMUNICATIONS1

Fifteen years ago, when William Shrank was starting a fellowship, health literacy was just becoming a topic of interest, thanks to the pioneering work of Terry Davis and Ruth Parker. “When you think about where the discussion was then and where the discussion is today, it is pretty extraordinary the amount of progress and change and to some extent, a

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by William Shrank, chief medical officer of the UPMC Health Plan, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

lack of coordination, but also an extraordinary amount of innovation,” said Shrank. He then noted how important it is today to look at the issue of health literacy and communication about medications in the context of the rapidly changing health care landscape. In this new era of paying for quality instead of for volume, providers are taking on more financial risk, which is leading them to become more concerned than ever about what happens to patients once they leave the doctor’s office. As a result, providers need to better communicate and engage with their patients. “It means that these measures that some of us have been doing research on for a long time are suddenly front and center in every primary care doctor’s office with regard to how their patients are taking their medications,” said Shrank.

This fundamental change, he said, creates a unique business context for a host of players in the industry to participate in efforts to improve communication with patients. Pharmacies, for example, are now partnering with health systems to support patients between visits to their doctors, and pharmacy benefits managers are creating a better infrastructure and collecting data for tracking whether patients are adhering to medication plans. Countless start-up companies are trying to find a niche in which they can support providers. The result, said Shrank, is that there is an enormous amount of attention, growth, and interest in understanding how to better communicate and support patients regarding their medication use.

Another fundamental change in health care that is germane to health literacy and medication adherence is the shift in cost sharing from employers to their employees. As a result, Shrank explained, patients are now educating themselves about price and quality like never before and are making provider choices based at least in part on such information. Patients today, he said, are looking for practices that explain more, that make their patients feel cared for, and where they believe there is some mechanism in place to help them manage their complex lives and medication regimens. “That means that anyone who cares about whether that consumer gets their care at their site or through their service sure better figure out how to communicate with that consumer,” said Shrank.

Shrank then claimed there is more investment in this area today than he could have ever imagined. As an example, he explained how CVS Health, a large retail pharmacy chain with a reputation for working with and focusing on consumers, allocates substantial resources to understand what words work in terms of patient communications, what messages work, what vehicles work, and how messages should be delivered. CVS Health also works with a remarkably deep set of analytics and predictive modeling, he added, to rapidly assess what is working or not working, and continually strive to understand how to get the right intervention to the right person. “These investments are driving the way CVS communicates with patients, the words they choose, the channels that they leverage, and the way in

which they are continually trying to improve,” said Shrank, who formerly worked for CVS.

Health systems, including the UPMC health plan where he currently works, are also investing a significant amount of energy in figuring out how to communicate better with its providers’ patients. “We have a rich, robust consumer innovation arm and have acquired probably a dozen companies specifically to help us use different kinds of technology and different kinds of data to better target and deliver the right intervention to the right patient regarding their medications or their chronic disease management,” explained Shrank. The focus of this work, which now involves more than 100 employees at the UPMC health plan, is on learning internally, improving continually, and running the business as well as possible, but with a “deep and profound commitment to understanding how we communicate with our patients best to deliver the very best care we can.”

One result from all of these efforts, said Shrank, is that patients may actually become overwhelmed with information. “A patient with diabetes and heart failure might be getting calls from many different sources,” he said. Another issue is that while the field is investing enormous resources in this type of research, there is no collaboration among organizations. “Ultimately, there is a great deal of inefficiency here,” said Shrank. “We are all studying many of these same questions, approaching them in many of the same ways, and leveraging many of the same analytics. A rising tide would lift all ships here if we were able to bring together all of these efforts, all of these resources, all of this speed, and all of this business urgency to create learning from which we all could benefit.” He has argued there is a business case for sharing what we have learned and publishing results. “It does allow you to differentiate yourself from your competitors and make a clear value-driven, mission-driven argument around what you are trying to do to help support your members or your patients or your customers,” said Shrank.

One important new factor is the explosion of tools to promote wellness and chronic disease. Fifteen years ago, medication labels were the only way to talk to patients about their medications. Today, a variety of tools, including online resources, mobile device apps, texting, and telephone approaches, exist for patients to learn about their medications. “This speaks to the fact that the kinds of questions we are asking and the kinds of interventions we can apply are expanding rapidly,” said Shrank. He noted it would be shortsighted to focus research on any one of these approaches at the expense of the others.

In addition, he said that not only are there many tools and vehicles for sharing information, but the messages themselves can vary. Messages can focus on education or risk, and can use techniques such as behavioral economics to encourage and motivate patients. Social networks are an

increasing source of information transfer and encouragement. “When you start layering all of these tools with all of these tactics, the number of permutations is quite enormous,” said Shrank. As a result, researchers need to be thoughtful about not just saying one works and one does not, but instead stating which intervention is right for which specific type of patient and saying how one approach compares to the other sets of innovations. The goal, he said, is to determine how to create a cohesive, coordinated approach to bring the right intervention to the right person without being wasteful or sending too many interventions to any given person. “How do you build the right system, a comprehensive, thoughtful system that can really help patients better take their meds?” asked Shrank.

Going forward, said Shrank, the health care environment is changing faster than anyone could have imagined even a few years ago and the movement to value will continue regardless of the change in administrations. “It is now hard-wired into how government pays for care and how commercial payers are paying for care, and increasingly it is being adopted by providers as their mission to deliver better care at lower cost,” he said. He predicted the result will be that the level of investment in this area will only increase, as will the need for those researchers attending this workshop to play a substantial role in refining, reforming, and encouraging the research community to play a different role in the marketplace. Researchers, he said, need to “embed themselves in a company or to partner deeply with a company that has scale, that has the ability to test and expand, that has the resources that can do things quickly. That kind of embedded approach would allow us to take into account all of the nuances, all of the different levers, all of the different approaches.”

As an example of this approach, Shrank cited the work Michael Wolf did on the Universal Medical Schedule, a methodology that simplifies medication instructions for patients and their caregivers. Wolf did some foundational work with Ruth Parker, Terry Davis, and to a lesser extent himself (Shrank et al., 2010), and then worked closely with companies in the marketplace to test this approach and then scale it (Wolf et al., 2016). In closing, Shrank added that embedding this type of work in health care and commercial organizations could provide a way of funding health literacy research.

THE ROLE OF HUMAN FACTORS ENGINEERING2

When it comes to designing labels and labeling information,3 what FDA hopes for is a design that translates into safe and effective use of the medications on the market by end users, including patients, caregivers, and health care providers, Chan explained. One goal of designing labels and labeling is to avoid medication error, which she defined as any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or provider. The key term here is prevention, she said, adding, “We are trying to prevent an event that could lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm.”

A 2007 report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2007) noted that labeling and packaging issues cause 33 percent of all medication errors. This report urged FDA to use human factors analysis to improve labeling information and nomenclature. Human factors analysis, she explained, is about understanding the interactions among humans and elements of a system with the goal of optimizing human well-being and overall system performance. “Putting those concepts together—medication error prevention and human factors—we see they are interconnected,” said Chan. “If we want to prevent medication errors, we have to be looking critically at human factors with the combined goal of ensuring that there is appropriate medication use and that we are optimizing human well-being.” With human factors engineering, it is possible to apply a process to the design of a system, in this case labels and labeling, to ultimately decrease the risk in that system, she explained.

Turning to the subject of the guidance FDA has issued regarding labels and labeling (CDER, 2013), Chan noted that much of this guidance was developed based on submitted reports from patients, manufacturers, and health care providers. These reports help the agency learn what is happening in the real world. She explained that FDA always encourages companies to understand their end users and the environments in which the information will be used when designing their labels and labeling. “We want sponsors to assess and obviously minimize the risk for medication errors that could be attributed to poor design of labels and labeling,” said Chan.

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Irene Chan, deputy director in the Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

3 FDA defines “label” as any display of written, printed, or graphic matter on the immediate container of any article, or any such matter affixed to any consumer commodity or affixed to or appearing on a package containing any consumer commodity, and “labeling” as all written, printed, or graphic matter accompanying an article at any time while such article is in interstate commerce or held for sale after shipment or delivery in interstate commerce.

“Then we encourage the use of human factors engineering processes and gathering data through human factors studies to help characterize the risk and develop risk mitigation strategies.” Human factors studies are generally smaller and quicker to complete than clinical studies, and for a small investment of resources, human factors studies can avoid the need to resolve issues postmarketing, she said.

In many cases, said Chan, designing for the user means designing for multiple end users. A product might be used by a 5-year-old and a 65-year-old, for example. “We have to understand all of the differences in the distinct patient populations and how they are going to impact how we design the products and their labels and labeling,” said Chan. Understanding the user means considering if users will have vision, hearing, or tactile sense impairments, or are challenged in terms of strength and dexterity. Users may have comorbidities, low health literacy, and differences in their ability and willingness to learn. They may use the drugs in different environments. All of these factors can affect how a user is going to interact with the labels, the labeling, and the packaging and how well they can comprehend the information put before them.

In February 2016, FDA published a draft guidance on human factors studies for combinations products (CDER, 2016). This document refers to two stages of development and associated studies, and the principles described can be applied to label and labeling design as well. Formative studies are iterative in nature and involve rapid prototyping, testing the resulting designs for their ability to convey key information to patients, and using the findings to refine labels and labeling. Validation studies could evaluate what a company believes are the labels and labeling it wants to use for commercial products in the market. Validation studies generate the data that can support the claim that the user interfaces, including the labels and labeling, provide effective information for end users that will lead to safe and effective use of a given drug. Chan noted that labels and labeling by themselves will not replace good product design. “Trying to use labels and labeling to overcome, if you will, the weaknesses in something that may have been poorly designed is not really the strategy that FDA is looking for companies to take,” said Chan. What FDA does expect is for manufacturers to study what they intend to put into the market and what they intend to submit in their marketing application. “We expect them to be evaluating the entire user interface—the connection points where a user, such as a patient, is going to interact with that product, and it includes the product itself, the packaging, and all of the labels and labeling that go on it and accompany it,” said Chan. FDA also expects companies to evaluate products on representative users in representative scenarios with the goal of observing where there may be errors and understand why those errors are occurring.

Manufacturers use another type of study, the knowledge task study, when FDA wants to know that labels and labeling convey certain critical information correctly. “There are some things that you cannot directly observe,” said Chan. “I can observe whether someone can hold an injection in place, but I may not be able to observe whether they understand if they have this particular indication or contraindication or if they are actively bleeding whether they should proceed with using the product.” Such studies, then, focus on the understanding and interpretation of important user interface information.

Within the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, the Division of Medication Error Prevention Analysis is responsible for evaluating human factors data for drug product submissions. Colleagues in FDA’s Office of Medical Policy also consult on labels and labeling and help ensure that instructions are readable as far as formatting and other readability factors are concerned and at the appropriate reading level. The Office of Medical Policy’s patient labeling team also makes sure that the patient package inserts, medication guides, and instructions for use employ simple words and concepts to help with patient comprehension and to ensure that unnecessary or redundant information is removed.

Going forward, said Chan, FDA is committed to the development of a new form of patient information, called Patient Medication Information, to help ensure patients receive essential information about prescription medications. FDA is proposing to amend medication guide regulations4 to require this new form of patient labeling, which fulfill the following:

- Provide clear, concise written patient prescription drug product information.

- Be required for human prescription drug products used, dispensed, and administered on an outpatient basis.

- Have a standardized format.

- Be submitted to FDA for review and approval.

- Be distributed to patients who receive prescriptions.

- Be intended for use at home, not to replace or affect professional labeling, instructions for use, or patient counseling.

- Be freely available and easily accessible to health care providers and patients.

- Be consumer tested during development.

___________________

4 The unified agenda listing Patient Medication Information is available at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=201604&RIN=0910-AH33 (accessed December 9, 2016).

The Patient Medication Information document would be required for human prescription drug products used, dispensed, or administered on an outpatient basis. It would have a standardized format, be submitted to FDA for review and approval, and be distributed to all patients who receive prescriptions. It would not replace labeling for professionals or the instructions for use, Chan explained in closing.

HUMAN-CENTERED DESIGN5

Although there are many definitions of human factors or human-centered design, Israelski favors one that says it applies data on human capabilities and characteristics to the design and evaluation of systems and devices, which can include a broad array of things, including drug labels and packaging, medical devices, smartphone apps, device and drug combinations, and websites. “Anything that has a user interface where the human has to interact, get information, process it, and then act is fair game for the field of human-centered design,” said Israelski. The field has existed for more than 60 years, he explained, and relies heavily on the methods of the behavioral sciences and engineering. He noted, too, that there are many synonyms for human factors or human-centered design, such as ergonomics, usability engineering, user experience design, user-centered design, cognitive ergonomics, macroergonomics, cognitive engineering, and human engineering. Regardless of what it is called, the goal is to make products efficient, safe, and easy to learn about and use.

As Chan noted, FDA requires human-centered design in certain applications, and as a result, many good products in the medical field were developed with the help of human-centered design. In Europe, companies wishing to acquire regulatory approval must follow international standards on human factors. Many U.S. companies now employ human factors professionals, most who have a degree in the field, said Israelski. Some people come into this multidisciplinary field via one of the engineering disciplines, while others are psychologists who are interested in applying their expertise to real-world problems. Some of his colleagues have clinical backgrounds, while others come from communication fields. A few people in the field have certifications in human-centered design.

Among the award-winning products designed using human factors is a glucose meter that operates like a smartphone and takes advantage of the fact that many people are now familiar with finger gestures such as pinching and swiping. This device, said Israelski, illustrates the advantages

___________________

5 This section is based on the presentation by Edmond Israelski, technical advisor on human factors and retired director of human factors at AbbVie Inc., and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

modern technology offers in terms of user interface design. So, too, does an infusion pump that has a large, readable touchscreen with a Windows-like interface that uses scrollbars, drop-down list boxes, radio buttons, and pop-up dialogue boxes. Not all human-centered design products are as complex as a glucose meter or infusion pump, he explained. Examples include an intravenous pole that is not only stable, but provides multiple places for mounting intravenous bags and storage space for an oxygen tank; ergonomic packaging for baby formula; and a hand-held, video-aided device for visualizing the vocal cords during intubation.

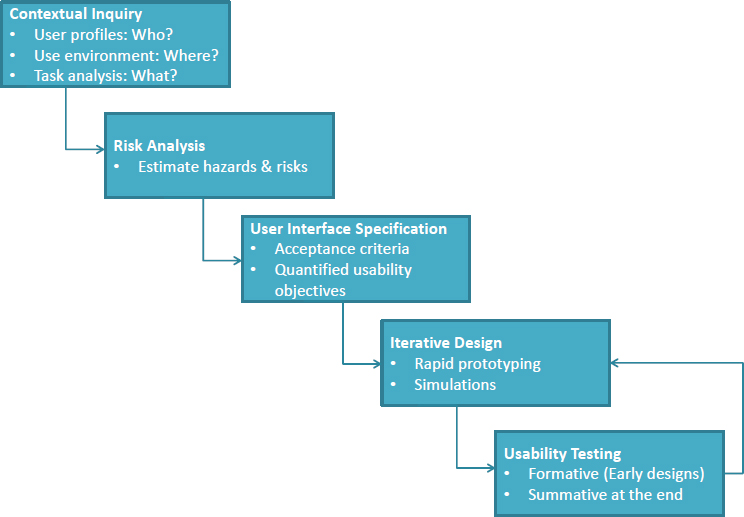

Israelski then described the core methods used in human-centered design (see Figure 3-1). The process starts with a contextual inquiry, which aims to understand who the likely users are and what their capabilities and limitations are, how the product will be used and in what type of scenarios, and in what environment the product will be used. Next, a risk analysis attempts to assess all the things that could go wrong when a product is in the hands of the user. This step aims to identify potential sources of error and understand how such errors might arise, whether it is because the product is lacking in some way or because users experience some type of failure, and it involves examining every task systematically for the possibil-

SOURCE: As presented by Edmond Israelski, November 17, 2016.

ity that something could go wrong and, if so, what the consequences would be. Risk analysis helps identify the most critical and error-prone tasks that would be the leading candidates for improvement, and it is repeated after every iteration of product design.

User interface specification follows risk analysis, and it can involve working on developing user-friendly navigation features for a smartphone app or the layout of instructional materials for a medical device, for example. This step involves creating detailed specifications for user interface and product design that leaves little room for creativity on the part of the development team, according to Israelski. Assessing whether the resulting user interface does what is expected from it is usually a qualitative process when it comes to products that FDA will review, said Israelski, because a quantitative study that produces precise human factors measurements typically involves thousands of people, making them impractical and expensive.

The hard part of the human factors method, said Israelski, is the iterative and rapid prototyping and testing process. In most cases, designers conduct these early usability tests in a one-on-one environment. This setup allows the designers to observe representatives doing these tasks in a simulated environment close to the expected real-world settings in which the user would encounter the product. Following what Israelski called the initial formative iterations, the product reaches a point where it is ready to undergo validation or a summative usability test to demonstrate that all of this work has created a product that meets all of the specified user requirements and is safe and effective. He noted that while this process is not simple, it does generate products that work for all users. “We do not yet have sophisticated technology that lets you design a user interface perfectly from the beginning that will work for everybody,” said Israelski. “Only through testing will you learn and iterate and make improvements.” Testing does not stop once the product passes the validation process, however. “There is postmarket analysis as well in which you can learn about things that did not necessarily show up in your early work, but do show up when the product is launched. Then you can take corrective action,” said Israelski.

Usability testing, he explained, is both formative and summative. Formative testing is done early with simulations and first prototypes. Its purpose is to explore user interface concepts, detect obstacles and design defects, and explore whether usability goals are attainable. This stage of testing does not necessarily have strict acceptance criteria. Summative testing, which is done in the final stage of design with the production equivalent, needs to have acceptance criteria such as usability goals for human performance and satisfaction ratings.

Addressing best practices in usability testing, Israelski said it is important to involve representative users, not just people who are convenient. If the intended users are patients with visual impairments, for example, then

the five to eight people recruited for formative testing should have similar visual impairments. “We often talk about having distinct user groups,” said Israelski, “and there is an art to defining them.” Examples of distinct user groups, he said, would be nurses versus physicians versus patients, where each group would be assigned different tasks with different levels of risk. The test subjects are given real tasks to do, particularly critical tasks related to safety, not just convenient tasks that might make users feel good to have accomplished. “If they are not the critical tasks related to safety or the ones that are essential to getting the product used correctly or the risk communication material conveyed correctly, then you are fooling yourself by not testing the real representative task,” said Israelski.

Another important step, he said, is to conduct testing in a realistic-use environment with regard to lighting, noise, and workflow. If possible, testing should use three-dimensional printed parts when testing physical products or computer simulations for products that are screen based.

Another hallmark of usability testing is asking users to think aloud and record what they do and say. It is possible to gain important insights when people are interacting with a product and the tester is encouraging the test subjects to explain what is confusing them. This “think-aloud protocol” can be helpful, Israelski said, in understanding what is going wrong in a design and where the opportunities are for making changes.

Summarizing the process, Israelski said it is systematic and scientific, and with respect to products that FDA will review, governed by rigorous design control specified by FDA. “You have to maintain a good design history file that is auditable, and you have to do formal risk management,” he said. FDA requires verification to demonstrate that design outputs meet design inputs and that user interfaces meet customer requirements. The agency also requires postmarket surveillance to ensure there are no unanticipated problems.

In his final remarks, Israelski reviewed some of the human factors standards that FDA and other organizations have issued for use with medical device testing. “Even if you are not designing medical devices, they are valuable to read,” said Israelski. “They tell you about the principles of human factors in some detail and how you might apply them to things like testing, risk communication, and success.” He noted that these documents are long, and following them can be daunting. The American National Standards Institute/Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (ANSI/AAMI) standard HE75, for example, is 500 pages long with supplements totaling another 850 pages, but it provides valuable “getting started” information and distills 60-plus years of human factors research into actionable information. Two recently released International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) standards, which were produced in conjunction with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), elaborate

on the human factors core methods Israelski described earlier and contain tutorials for all of the methods of human factors (see Box 3-1). FDA, said Israelski, recognizes all of these standards and was heavily involved in writing them. In addition, as Chan discussed, FDA has issued several guidance documents, including one released in February 2016 that elaborates on FDA’s expectations for applying human factors to medical devices.

DISCUSSION

Bernard Rosof opened the discussion by asking the panelists if human-centered design will differentiate a product in the marketplace with the economic buyer and if there are metrics to determine that. One metric, said Israelski, is whether the product succeeds in the marketplace, that people like it, adopt it, and it helps them. Diabetic patients, for example, will gravitate to glucose meters that are easier to use, less confusing, have displays that are clear and easy to read, and that track more complex factors such as meal marking and exercise. Another metric is compliance—does a product or piece of information help patients comply with their medication plans or comply with usage of a medical device? Products that improve compliance will create health, economic, and outcomes metrics that demonstrate the value of a product and that can be compared across products. Chan agreed that the marketplace is the ultimate judge of whether a product is well designed. Ultimately, she said, products that create problems such as medication errors will influence patients’ willingness to use them and to recommend them to fellow consumers. She also noted that companies are starting to conduct likability testing as a means of differentiating their

products, and she expects to see more of this as sponsors become more interested in how likability can affect labeling claims.

Jay Duhig from AbbVie Inc. commented that the speakers in the first panel session stated clearly that patients needed to be included more in the resource development and tool development process and that the second panel described a very systematic method for doing so, collecting data, and then creating user-centered tools in an iterative process. He noted that both Israelski and Chan had influenced a wide range of groups that are creating materials and asked if they had any thoughts on how to get organizations to increase their inclusion of patients when they develop resources. He also asked them for ideas on how to get organizations to adopt practices that reflect the research on human factors, health literacy, and usability. Israelski suggested publicizing case studies in which human-centered design has been applied successfully to develop materials that patients, physicians, health care providers, and payers find useful, particularly if they are accompanied by business cases. He said that good human-centered design that can improve patient compliance is better for patients and for payers. Demonstrating benefits from the perspective of patients and health economics is one way of getting these methods adopted more widely, he said. Chan agreed that getting consumers more involved in the design of medication materials is a key aspect of getting patient-centered design widely adopted.

Israelski recommended a book, Cost Justifying Usability, by Randolph Bias and Deborah Mayhew, that presents business cases showing how human factors can produce an economic return to the companies employing its methods. As an example, he said that many medical products suffer recalls or returns that are tied to usability issues. “If you can show in a little business case that you have put a dent in that rate—say it was originally 10 percent and now you bring it down to 5 percent—you can put a dollar value onto that increase in customer acceptance and decrease in complaints.” Compared to the outlay for human factors, which is typically small compared to that of clinical trials, the return on investment will be high, said Israelski.

He also pointed to the importance of regulatory power. For example, before the human factors group moved to the FDA Office of Device Evaluation, it was simply a consulting group that was not required to be involved in every review. They are involved in the review process today, and the result, he said, has been “amazing” in that companies are now creating human factors groups. “This is all due to FDA,” said Israelski, who added that big pharmaceuticals did not have human factors groups before this change at FDA. “This has been a great boon for people in human factors as a profession,” said Israelski.

Ruth Parker said that Chan’s remarks about FDA’s emphasis on health literacy and involving patients and payers was “music to my ears” and an

important sign of progress. She then asked Shrank to comment on what happens to products designed using human factors once they reach the market and how health literacy plays out in the postapproval world. Shrank replied that postmarket surveillance research today is generally epidemiologic in nature and leverages large databases. “It looks at rates of clinical outcomes by patients depending on what meds they are taking and what combination of meds they are taking, but there is little nuance around the patient’s experience of how they take their meds,” said Shrank. As to why some medications work better than others in the real world, he said there are biologic and genetic reasons, social reasons beyond adherence, the way in which drugs are administered, and the ways in which patients manage their lifestyles. “I think the concept of a much richer, patient-centered view of data collection could allow for a much richer and more nuanced way of understanding more about safety, efficacy, and adherence in the postmarketing surveillance time period,” said Shrank. “I do hope that is something that could be expanded on.”

Chan, speaking from FDA’s perspective, said the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research uses the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, which receives millions of reports from manufacturers, as a major data source. It also relies on reports consumers and providers submit directly to the agency and from patient safety organizations such as the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Each of these data sources is important and scrutinized by FDA, said Chan, for they identify where patients and providers are finding difficulty understanding medication information. She believes the marketplace provides the only true test of how understandable medication materials are. “Whatever the manufacturers do in terms of simulated testing before they bring something to market is not going to compare to getting it into the hands of potentially millions of users and then seeing what gets reported to the agency,” said Chan. “Postmarketing is very important for the agency and something we pay attention to in driving policy recommendations,” she said.

Israelski commented on the rise of social media and said both patients and members of the health care system are gleaning a great deal of postmarket information from Facebook and Twitter as well as websites devoted to specific diseases. “People readily tell their stories,” he said. “On YouTube, you can find people teaching you how to deal with side effects and the risks of certain medications and therapies with a great amount of detail.” In his opinion, these social media outlets and websites create an opportunity for patients and families to learn about various health conditions and to educate themselves about the pros and cons of different therapies and alternatives so they can ask intelligent questions of their doctors before making health care decisions. “There is the downside of too much information and some of it being bad, but I think on the balance, what we have available

to us is a wonderful thing. I think it makes postmarket surveillance even richer because of that,” said Israelski.

An unidentified workshop participant asked the panelists for examples of approaches that have worked, and Shrank provided several examples of how CVS used human factors to develop a variety of approaches on how patients administer their medications. One approach synchronizes all of a patient’s prescription refills on the same day of the month so they do not have to make multiple trips to the pharmacy. Another tactic creates multidose packs containing all of a patient’s morning doses in one pack and their evening doses in another pack. “This is a much simpler way to administer a complex drug regimen,” said Shrank. CVS has also created a series of incentives to encourage people to engage in healthy behaviors, including one in which they leveraged behavioral economics to get people to stop smoking (Halpern et al., 2015).

Israelski noted that AbbVie has had a number of successes using human factors in its product designs. For the biologic drug Humira, which has been approved to treat a number of autoimmune diseases, AbbVie created supportive apps for patients and a talking training pen and video to teach patients how to inject the drug properly. These tools have worked well enough that there is a very low rate of patients not being able to use the injector successfully, which is a big part of compliance. The company used human factors to design packaging and labeling for hepatitis C drugs and for complicated regimens of oral oncology drugs. “The packaging and labeling designs have to be done right to get those schedules understood and used properly by patients to get the drug to be used safely and effectively,” said Israelski. Human factors helped AbbVie design an ambulatory infusion pump for Parkinson’s disease that individuals with impairment caused by tremor and stiffness can use. “The company has embraced human factors and seen the pay-off,” he added.

Elisabeth Walther from the Office of Medical Policy at FDA responded to a question about a proposed rule change that would require a one-page patient-centered medication information sheet to accompany all drugs dispensed or administered on an outpatient basis. She noted that this rule change has been included on the spring 2017 Unified Agenda, which lists the regulations FDA expects to publish within the next year. Chan added that the industry now realizes that ensuring patients know how to use a drug is part of FDA’s consideration as to whether a product is safe and effective. “That has been a message that we have been trying to drive home to our stakeholders,” said Chan.

Rosof noted that the issue of medication safety and health literacy was first raised in 2000 and 2001 with the release of two Institute of Medicine reports, To Err Is Human (IOM, 2000) and Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001). These two reports described quality as a systems property,

yet he has not heard a discussion about these issues within integrated delivery systems, including his own. “What are we missing here in terms of translating this discussion to where medication use is a real issue?” asked Rosof. Shrank replied that there is a clearer sense of what needs to be done in the somewhat controlled environment of a hospital and there has been an extraordinary effort and success with regard to medication safety in that environment. Doing the same thing with patients in their homes is more difficult, he said, in part because “the patient may not always be aligned in terms of what their perceptions are of success. Patients have varying views about the value of their medication and how they feel about their medication. If the patient at any point is not aligned, that is going to be a very hard thing to overcome,” said Shrank.

Another contributor to this challenge, he said, is that so many social factors affect a patient’s decision about how to take their medications at home, making it difficult to create a systematic approach that addresses them all. “Things such as the cultural features of taking medication, the cost of taking medication, the unexpected fact that your car broke down and you cannot get to the pharmacy, or your arthritis is acting up and you cannot open the bottle” were factors that Shrank described. “The number of permutations of potential barriers is almost infinite.” The answer, he added, is to keep creating better systems, such as multidose packaging, and engaging in efforts to help support, engage, and motivate patients. He acknowledged, though, that the weakest point in the system is when patients are discharged, particularly when patients have to reconcile the medications they receive at discharge with the medications they have at home. UPMC pharmacists now do a face-to-face medication reconciliation with patients at discharge, which Shrank said is having a positive impact on compliance and safety.

Rosof then asked Chan if FDA was satisfied with how health systems are performing in this regard. She replied that safety issues in a health care system do not fall under FDA’s purview. She added, however, that her division at FDA thinks a great deal about the entire medication use system. “We think about how that product is traveling through all of the different settings of care and whose hands are on it and who is interacting with it when we think about how we want to make recommendations or what recommendations we want to take,” she explained. Historically, she noted, the agency took a reactive approach, where it would react to a postmarketing issue, but today the agency is more proactive at identifying points in the medication use system that are vulnerable to failure. “We expect that manufacturers are going out there and really understanding their users in their home environments and their settings of care to design a better product,” said Chan. She believes that while some of that work aims to meet FDA requirements, companies are intentional about designing a product that can be used safely and effectively in the hands of its customers. “I think

it is important to underscore that that kind of research can be done early in development by manufacturers,” Chan added.

Daniel Morrow from the University of Illinois commented that while he had heard about the potential of technology for integration and improving the patient experience and the crucial role of human factors in realizing that potential, he has not heard anyone discuss the potential for the electronic health record (EHR) to be the lynchpin of the synergy between the health care system and the home. He asked if FDA is playing a role in promoting the use of EHRs to support self-care in coordination with their providers. Walther replied that FDA has in fact considered that issue when it developed the proposed new Patient Medication Information rule and has included flexibility in the rule that should enable EHR vendors to develop applications that could support better communication between the health care system and the patient at home.

Israelski commented that a company such as AbbVie has to embrace the entire health care ecosystem and how its products fit into the patient journey. “We have meetings where we look at the patient journey from diagnosis to original prescription to titration, maintenance, and hopefully, cure or stable conditions,” he said. This mapping exercise enables the company to identify the things it can develop, such as training materials, doctors’ aids, and other types of information, to help enhance the patient journey through the health care ecosystem. One question AbbVie is asking, he added, is how supportive features such as apps and websites integrate with the EHR to improve the patient journey.

Shrank noted that UPMC has a care management tool that integrates with the EHR. Care managers, nurse practitioners, allied staff, and pharmacists use this tool to manage patients and coordinate their care over time. “For us, it is not an EHR thing. It is finding the right place within the workflow that delivers the right information to the person that is going to do the outreach,” he explained.

Darvece Monson remarked that she appreciated both the opportunity to hear from those who are working on these problems and how difficult these challenges are to address. She then said that simplicity is what empowers patients, and therefore simplicity is the most important factor to remember when designing products. As an example, a warning that a drug may cause a decrease in blood pressure could be accompanied by a link to a webpage that explains exactly what that means and describes the signs of a decrease in blood pressure. “Something as simple as that can help the patient become more empowered and involved in their care,” said Monson.

Walther ended the discussion by stating that FDA values anytime patients can provide the agency with information on what they need. “It really does influence what we do,” said Walther. She encouraged patients to contact FDA with their concerns at patientmedicationinformation@fda.gov.

This page intentionally left blank.