4

Translating Research into Practice: Case Studies

The workshop’s third panel session featured four case studies illustrating how health systems are translating research into practice. Steve Sparks, health literacy director for Wisconsin Health Literacy, described a statewide effort in Wisconsin to adopt health-literate medication labels, and Laurie Myers, global health literacy director at Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., discussed the importance of including individuals with low health literacy in efforts to develop new medication labeling for patients. Brian Jack, professor and chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine, reviewed Project RED, an effort to reduce rehospitalization using a redesigned discharge process, and Charles Lee, president and founder of Polyglot Systems, spoke about approaches for providing medication information to non-English speakers. Following the four presentations, Donna Horn, director of patient safety–community pharmacy at the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, and H. Shonna Yin, associate professor of pediatrics and population health in the Departments of Pediatrics and Population Health at the New York University School of Medicine and Bellevue Hospital Center, gave their reactions to the four presentations. An open discussion moderated by Bernard Rosof followed the comments from the reactors.

ADOPTING AN EASY-TO-READ MEDICATION LABEL IN WISCONSIN1

As an introduction to his presentation on Wisconsin Health Literacy’s efforts to improve medication labels in Wisconsin, Steve Sparks noted that whenever he talks about this work, he hears stories about how medication errors have led to near disasters. “The stories we hear serve as a constant reminder of just how important our work really is,” said Sparks. His work, he explained, began shortly after U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) issued new patient-centered labeling guidelines in 2013. The Wisconsin Partnership Program of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health provided funding for this work.

Phase 1 of this project involved interviewing pharmacists and pharmacy managers working at both independent and chain pharmacies, as well as representatives from companies that provide software used to generate labels in those pharmacies. He and his colleagues also interviewed physicians and stakeholders from states that had already implemented patient-centered guidelines. These interviews revealed that most pharmacists were not aware of the new guidelines or had forgotten USP had issued them. However, once the new guidelines were explained, pharmacists supported them, believed they would improve readability and reduce confusion, and believed they did not need additional evidence to convince them to adopt the new label given the clear benefits of doing so. The pharmacists also thought the guidelines were compatible with current pharmacy workflows, though they were concerned about the limited space on labels and the flexibility of pharmacy software programs to produce labels meeting the new guidelines. Other potential barriers pharmacists mentioned included organizational acceptance and the cost of buying new label stock. The pharmacists mentioned that many customers request the medication’s purpose on their labels, but explained that most pharmacies do not have access to that information. The interviews with stakeholders found that while some states have patient-centered label standards in place, only one state had tried to mandate the USP standards, and this effort was not as successful as anticipated.

Energized by the findings of the first phase of this project, Wisconsin Health Literacy applied for and received a grant from the Medical College of Wisconsin’s Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment to pilot redesigned labels in 52 pharmacies in the southern and eastern parts of the state. The pharmacies included those serving low-income neighborhoods, rural areas of the state, and health care systems. Together, they issue 1.8 million

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Steve Sparks, health literacy director for Wisconsin Health Literacy, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

prescriptions per year, and each of the three pharmacy systems involved used a different pharmacy software: Rx30, EnterpriseRx by McKesson, and PioneerRx. “This was valuable to us because it will give us experience in expanding implementation to more pharmacies in the future and looking at how the process may be implemented or may be impacted by the individual software that they are using,” explained Sparks. The goal of phase 2 of this project is to implement and evaluate the USP guidelines by redesigning labels in the pilot pharmacies by the end of 2017 and use the experience gained in this pilot phase to more efficiently and smoothly implement the standards statewide in the project’s third phase. He noted that based on earlier research and the experience of other states, Wisconsin Health Literacy will pursue a voluntary adoption strategy rather than a mandatory one.

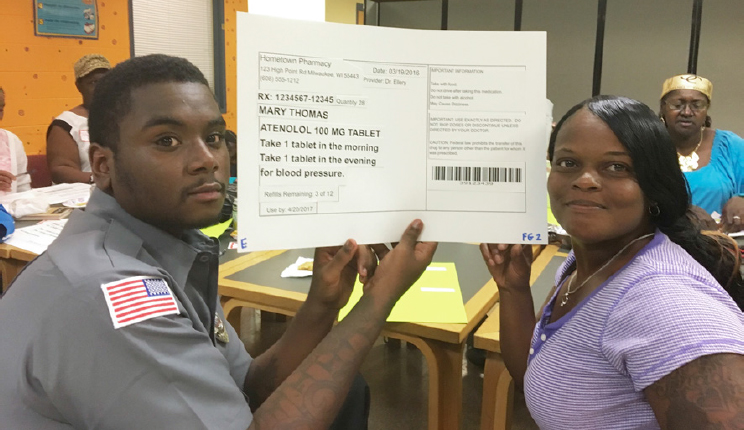

As part of the phase 2 pilots, which began on January 1, 2016, Wisconsin Health Literacy established a project advisory committee that included pharmacy partners, health literacy experts such as Michael Wolf, and representatives from USP, the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin, and Epic, the electronic health record (EHR) vendor that happens to be located in Madison, Wisconsin. Phase 2 also included patient focus groups made up of individuals who Sparks described as those who “typically may not have had a voice in a project such as this but whose input is essential for the work that we’re doing.” The focus groups, he explained, were helpful in determining what information should be included where on the label. He noted, too, that one of the most interesting activities had the focus groups design their own labels (see Figure 4-1).

SOURCE: As presented by Steve Sparks, November 17, 2016.

One benefit of involving focus groups, said Sparks, is that the enthusiastic members were willing to share their stories about medication issues. “One woman told us she had a terrible experience because she was taking care of her mother, who had diabetes. She had all kinds of medications that she was giving to her mother, was so confused about the instructions, and was just afraid she would do something that would be disastrous to her mother and her mother’s health.” Other comments, though not directly applicable to the project, said Sparks, were thought provoking. For example, some focus group members believed pharmacies are here to help, but others held the strong opinion that pharmacies just want to make money. “And another observation, perhaps the most interesting,” he said, “was the perception that pharmacies give lower quality medication to the poor.” A number of people in the focus groups, he added, believed that generic drugs were given to the poor.

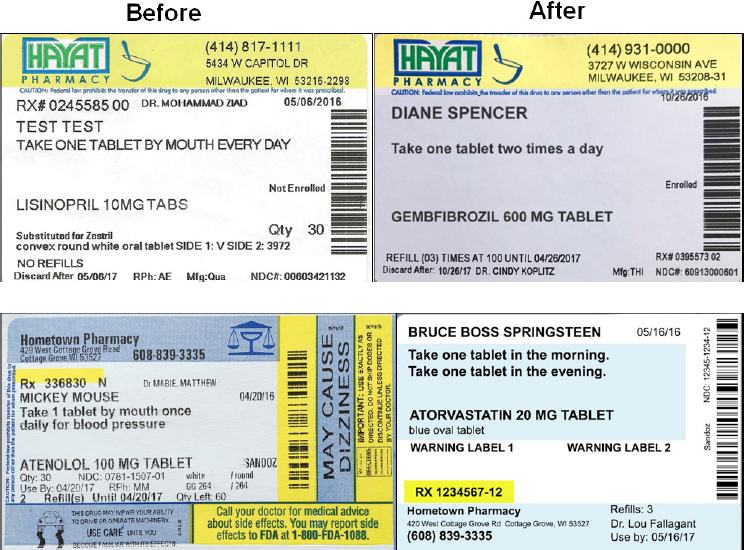

Sparks and his collaborators also started a patient advisory council made up of community members, one of whom is also on the project advisory council. The patient group meets quarterly and examines and comments on surveys and other communications. By working with these different groups, his team has produced several labels, still in the working-draft phase (see Figure 4-2), that pilot pharmacies will use starting in December 2016.

On April 3, 2017, Sparks and his team members will hold a day-long medication label summit featuring testimonials from the participating pharmacy members, as well as presentations by health literacy experts such as Wolf and Ruth Parker. This event, said Sparks, will serve as a key opportunity to share learnings and encourage other pharmacies to adopt the new labels in phase 3. One lesson learned so far is that each pharmacy has its own process and a unique relationship with the software vendor. “You cannot work with a pharmacy without working directly with the software vendor,” he explained.

A second lesson is that every pharmacy differs in how it wants to adopt new labels. Some, said Sparks, are willing to throw out all of the old label stock and start from scratch. Others have tens of thousands of labels in a storeroom that they want to use, which leads to work-arounds that can apply new standards to old color blocks and logo placement. Some pharmacies, he noted, insist on including information not in the USP guidelines and not required by law, but important to their workflow. One pharmacy, for example, wants to include the National Drug Code number—a unique 10-digit number that identifies the labeler, product, and trade package size—on the label, and several want to include the medication description. “While still adhering to the USP standards, we were able to be flexible and accommodate these requests,” said Sparks.

One important lesson is that pharmacy team involvement in label redesign and implementation is critical for success. “It was important the

SOURCE: As presented by Steve Sparks, November 17, 2016.

pharmacies felt we were working with them to come up with the new labels and the processes, not just giving them a set of standards they had to adopt,” said Sparks. “I do not think that would have worked, and as a result, the process is going much smoother and faster.” In the same vein, involving major stakeholders, including pharmacy boards and major pharmacy chains, makes for a smoother adoption process. Representatives from major pharmacy chains, he said, have been largely positive about this project while acknowledging the challenges of working across multiple sites.

Several issues also arose during the label design process that will require further study, largely related to the complexity of resolving those issues and the outside systems that would have to change as a result. The example Sparks cited was that adding the medication purpose on the label will require a massive change by providers and in the EHR software. Another issue involves how to standardize medication dosage instructions, for which there are no universally accepted standards.

In closing, Sparks said the next steps in this project will be to work closely with the partners to monitor implementation. “We are going to be

surveying patients in three pharmacy systems to see if they notice a change and if they like the new labels.” One of the three systems, he said, is a Medicaid health plan serving one of the pharmacy systems, providing the opportunity to analyze medication use before and after the new labels. “We look forward to learning more and applying the information to broader interpretation and implementation of patient-centered labels across the state in the third and final phase of the project, which we hope will start in 2018,” said Sparks. “We believe that the journey to better medication labels has begun and that the project could have implications well beyond the borders of Wisconsin.”

INCLUDING INDIVIDUALS WITH LOW HEALTH LITERACY IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND TESTING OF PATIENT LABELING2

Laurie Myers, who has led Merck’s health literacy work for the past 6 years, discussed how she and her colleagues included individuals with low health literacy in their work in developing and testing health-literate patient labeling for new molecules. Summarizing the key message of her presentation, Myers said, “It is important to include respondents with low health literacy. It will not happen by accident. You have to be thoughtful and make sure you do it in a systematic way, but it will give you a product that is much, much better.”

The overall goal of this project, she explained, has been to maximize comprehension of patient labeling for all audiences. “We knew we wanted to do this a number of years ago, but we were not quite sure how,” she said. One lesson she has learned is that it takes the involvement of multiple stakeholders to make this kind of change, including, for example, the company’s attorneys who believed it was possible both to be clear to patients and to follow the letter and spirit of the law. Another lesson is that the project had to start somewhere, so she and her team began with new drugs the company was developing. “This is not about looking backward, this is about looking ahead and proactively developing health-literate labeling for new molecules,” Myers explained.

What she and her colleagues realized was that while Merck has always been committed to clear patient labeling, and had previously included individuals with a broad range of education levels in its labeling design efforts, that research included few individuals with limited health literacy. Most of the people volunteering for Internet-based research on patient labels had adequate health literacy, so she and her team had to put

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Laurie Myers, global health literacy director at Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

into place different health literacy assessments to ensure they had enough people with low health literacy on their test panels to make a systematic assessment of how well panel members understood the information on patient labeling.

Merck’s revamped process for developing and testing patient labeling for new drugs starts with creating draft labeling that is accurate and consistent with physician labeling. Health literacy experts, including Parker, Wolf, and their teams, then review the draft labeling and suggest changes based on best practices in health literacy. After Merck reviews and approves the suggested changes, Parker, Wolf, and their teams conduct focus groups in Chicago and Atlanta that not only review the labeling for readability and clarity, but also help develop descriptions for concepts that the team is not sure how to explain in common language. For example, the focus groups might suggest words that could be used to describe a specific type of skin rash based on a picture. The company also conducts qualitative research with limited and adequate health literacy respondents to ensure the revised labeling is well understood across a range of health literacy levels. This iterative process of redesign and retesting reflects the importance of listening and responding to patients and caregivers.

To recruit individuals with low health literacy, the agency that conducts the qualitative research (Sommer Consulting) goes to places such as literacy centers and senior centers. They also included patients over age 70, as appropriate, who historically may have been excluded from such studies. Myers noted that in one recent comprehension study, two-thirds of the participants were over age 65. This change in recruiting processes illustrates the importance of questioning assumptions, said Myers. The recruitment process also includes a one-question health literacy screen in which potential respondents are asked how confident they are at filling out medical forms by themselves. This is done to make sure that there is adequate representation of participants with low health literacy. At the end of the comprehension testing, participants are also given the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) assessment, the results of which Myers and her team use for a final classification of the health literacy level of the panel members. “When you think about managing your health and managing your disease, numeracy is such an important part of that, and the NVS gets at that better,” she explained. She noted that Schlesinger Associates, which many companies in the pharmaceutical industry use for market research recruitment, is now adding the one-question health literacy screen to the profiles of potential participants in its subject database.

The recruitment goal for comprehension testing is to have 25 percent of the participants be individuals with low health literacy. “Sometimes we do not get there, but we usually come close,” said Myers. She added that the risk factors for chronic disease are often the same as the risk factors for low

health literacy, further pointing to the importance of including individuals with low health literacy in labeling assessments.

Today, the qualitative research (comprehension testing) is conducted both in-person and online. It is easier to recruit respondents with low health literacy to in-person market research. An important part of this effort, she explained, is to work with a market research company that is sensitized to the principles of health literacy and to treating low health-literacy individuals, who may not always be confident talking about medical information, with respect and dignity. “These are the kinds of soft things that make this successful,” said Myers. Her team now does both open- and closed-book assessments. Closed-book assessments provide insights into whether people, without being able to look at anything, can say, “What is it for? How do you take it? What are the serious side effects? What are the common side effects?” she explained. However, in the real world today, people go online when they have a question about a medication, making it important to include open-book testing as well.

Another change to Merck’s assessment procedure is that it no longer includes the requirement that people have a computer to participate in comprehension testing. “We used to require a desktop computer, but many people of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to have a phone, not a desktop, to access the Internet,” explained Myers. This inadvertently excluded those people from qualitative research, she added. The company also starts the recruitment process earlier than it used to because it takes more time to identify individuals with low health literacy.

Myers presented the overall results of multiple rounds of qualitative research testing patient labeling. The results showed there was high comprehension by respondents with both adequate and limited health literacy. Today, when Merck submits its patient labeling for new molecules, the company provides a brief summary of the results of this research to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to demonstrate that the company has evidence the label is well understood.

While in general it is true that people with less education have lower levels of health literacy and that those with more education have higher levels of health literacy, education is not a perfect proxy for health literacy. “The amazing thing is, people with more education are more likely to have higher comprehension, but even people with even only some high school are able to understand [the patient labeling developed from] this process,” said Myers. The same is true of age, where comprehension among older adults may be a little less, she said, but even people who are older are able to understand the new patient labels.

Not surprisingly, said Myers, patients love the new draft patient labeling. In follow-up interviews, participants say that health-literate labeling would make it likely they would read the information, keep the informa-

SOURCES: As presented by Laurie Myers, November 17, 2016. Copyright © 2017 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc. All rights reserved.

tion as a reference, have a clear understanding of how to use a medication correctly and the risks involved, and be able to ask questions of their providers. One request that participants have made is for labeling to include information about the risks and benefits of their medicines, though Myers acknowledged that type of information is not something that is likely to be included in the near future.

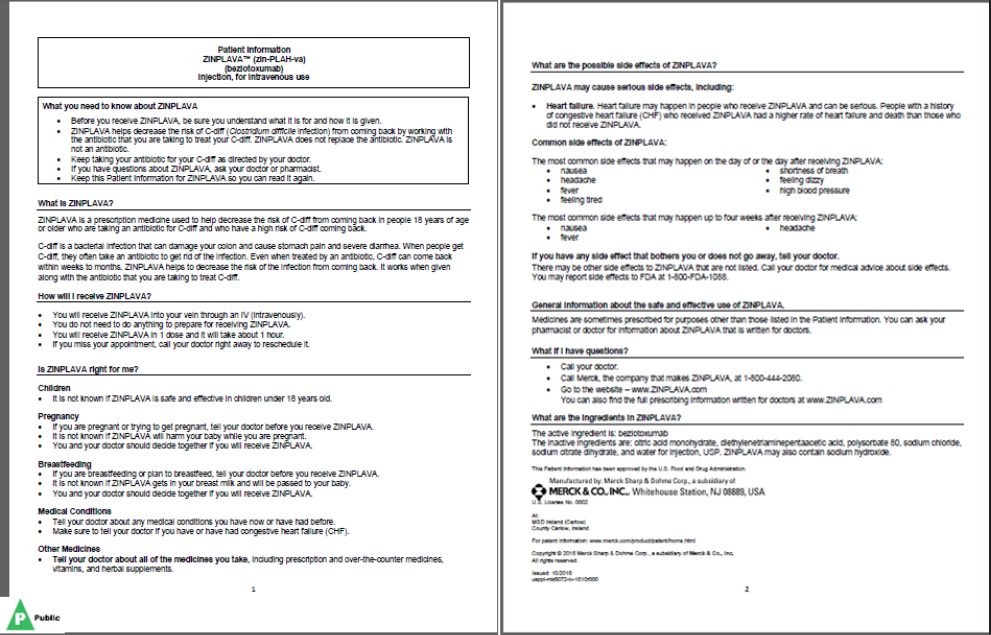

As an example of labeling created through this process, Myers showed the FDA-approved labeling for ZINPLAVA3 (see Figure 4-3). She gave FDA kudos for supporting Merck’s efforts to apply health literacy principles to the development of its patient labeling.

In a new project, Myers and her team, in partnership with Wolf, Parker, and their colleagues, are using a similar process to develop and test the Instructions for Use document. “The long and short of it is, this is working well and much like with patient labeling, we have to have an open mind,”

___________________

3 For full prescribing information, or any future labeling updates, please see the physician and patient labeling available at www.zinplava.com.

she said. For example, in the first prototype developed, instructions used to say “swirl for 30 to 60 seconds,” which meant the patient had to have a watch or use their phone. Instead, instructions now say “count to 45,” which she said is much easier than having to use a clock. “Little things like that that just are really about thinking differently and thinking innovatively,” said Myers. The initial results of testing these new instructions have been positive. Based on early results and testing, even people with limited health literacy have had more success in measuring and mixing medicines safely, she said.

In closing, Myers said that just because this process works in patient labeling does not mean it will work automatically in other types of consumer research without careful thought. “You have to think about this one project at a time,” she said. “It is possible, though, to develop information about new products that is simple and clear and easily understood by people of all health literacy levels.”

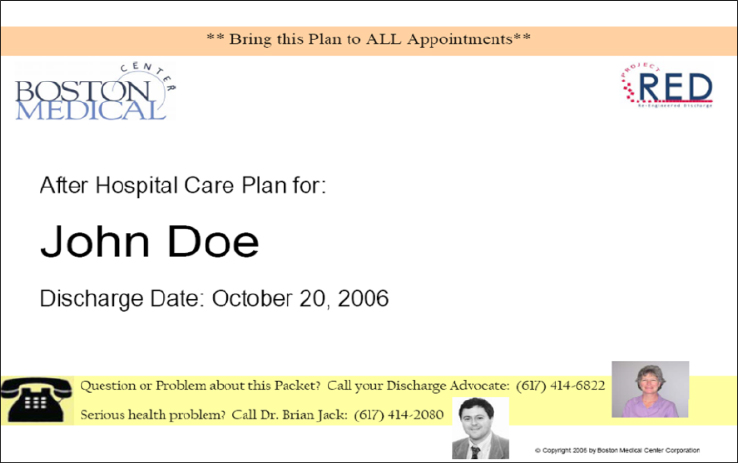

PROJECT RED: ENGAGING PATIENTS IN MEDICATION MANAGEMENT AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE4

Brian Jack began his presentation by listing the 11 mutually reinforcing components (see Box 4-1) of the Reengineered Discharge Program (Project RED) that he and his colleagues developed with the assistance of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (Jack et al., 2008; Mitchell et al., 2010, 2012). Medication reconciliation sits at the top of this list because it is the most important component of a health-literate discharge program, said Jack. Other critical components, he added, are the written discharge plan—a health-literate document that patients and their caregivers can use at home—and an assessment of patient understanding using techniques such as teach-back and a follow-up telephone call, again to measure understanding and to answer questions. He noted that the discharge plan is different from the discharge summary, which goes to the patient’s primary care provider. In 2006, the National Quality Forum adopted Project RED as the standard for hospital discharge and as the 11th of 30 Safe Practices (NQF, 2006).5

To test the effectiveness of Project RED, Jack and his colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled trial on 749 patients who received usual care or the RED intervention (Jack et al., 2009). In the intervention, a nurse acts as the discharge educator, collecting information from clinical

___________________

4 This section is based on the presentation by Brian Jack, professor and chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

5 It is now the 15th of 34 Safe Practices listed in the 2010 update (NQF, 2010).

staff, packaging that information, and then teaching the patient how to use this information in their posthospitalization care. The nurse educator also reviews the formal after-hospital care plan with the patient, uses teach-back methods to ensure the patient and family members understand the plan, and relays the plan to the patient’s primary care provider. A clinical pharmacist calls patients 2 to 4 days after discharge to reinforce the discharge plan and review medications. The results of the trial showed that fewer patients who received the Project RED intervention had to return to the hospital for any reason compared with patients who received the then-standard discharge process.

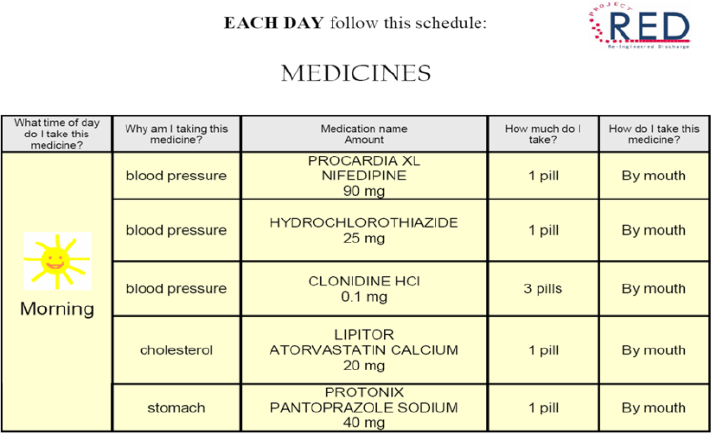

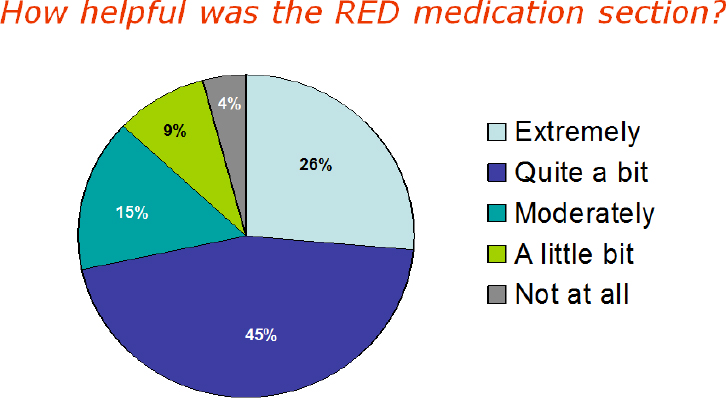

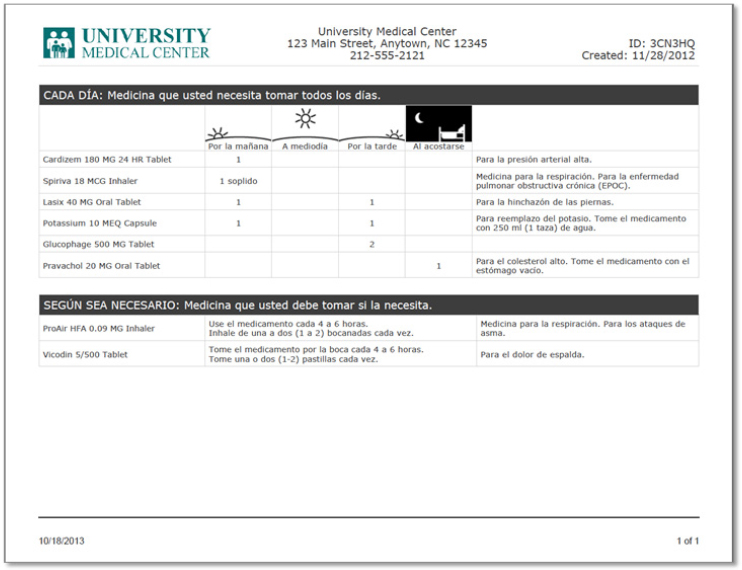

Focusing on the after-hospital care plan, Jack said that he and his colleagues spent a great deal of time thinking about how to create this document so that patients of all levels of health literacy would have the best chance of understanding what they needed to do after leaving the hospital. The resulting document makes liberal use of white space, large fonts, pictures, and icons (see Figure 4-4), and the medication component is structured to answer the four questions that focus groups identified as the most common that patients want answered: What time of day do I take this medicine?, Why am I taking this medication?, How much do I take?, and How do I take this medicine? (see Figure 4-5). An important aspect of the medication page, Jack noted, is what it does not contain: information about pathophysiology or mechanism of action. An evaluation of the after--

SOURCE: As presented by Brian Jack, November 17, 2016.

SOURCE: As presented by Brian Jack, November 17, 2016.

SOURCE: As presented by Brian Jack, November 17, 2016.

hospital care plan showed that a majority of patients found the medication section extremely, quite a bit, or moderately helpful (see Figure 4-6).

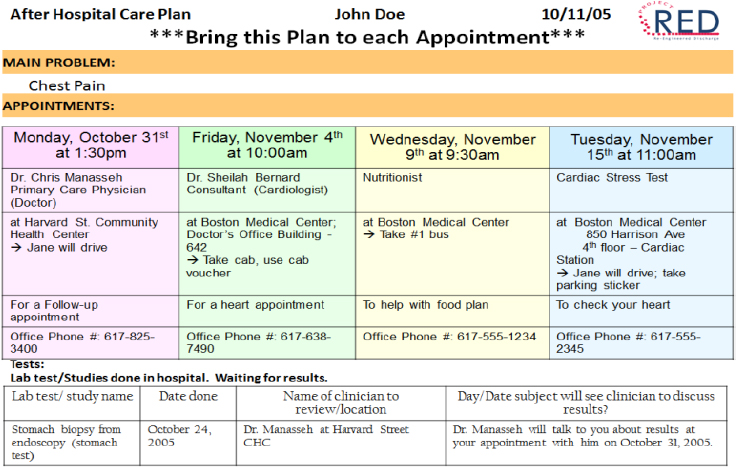

Another section of the after-hospital care plan lists the patient’s scheduled follow-up appointments with care team members and for laboratory tests (see Figure 4-7). It also includes any delivery scheduled for required medical equipment, such as a hospital bed or oxygen. An accompanying calendar, color coded to correspond to the appointment list, provides another way to make sure the patient and caregivers know about what is in store for the patient over the next 30 days.

Discussing the results of the clinical trial in more detail, Jack explained that the Project RED intervention was effective at reducing rehospitalization rates in patients of all health literacy levels. “Across the board, people found it helpful, and it decreased readmissions,” said Jack. He also noted that the intervention performed better than the usual discharge process on secondary outcomes, such as knowing the dates of follow-up appointments and the primary care provider’s name, as well as on self-prepared readiness for discharge. He pointed out that the Project RED team conducted these assessments 30 days after discharge, when most patients are not going to remember what happened in the hospital. “They do remember there was something about their discharge that was different and better,” he said.

SOURCE: As presented by Brian Jack, November 17, 2016.

Since this initial study, Jack and his collaborators have applied Project RED in the various units within their hospital. An inpatient Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey administered by Press Ganey showed the intervention produced statistically significant improvements in patient understanding of their discharge instructions compared to patients in the same hospital unit and throughout the hospital over the same time period. “You can raise HCAHPS scores based on the quality of the education related to discharge using the Project RED after-hospital care plan tool,” said Jack.

He then noted that the clarity of communication around medicines is more complicated than is often appreciated, particularly when a patient has multiple conditions or multiple complicating factors such as low health literacy and depression. A syndemic, he explained, is the aggregation of two or more diseases in a population in which there is some level of positive biological interaction that exacerbates the negative health effects of any or all of the diseases. To illustrate this, he described Project RED data on the relative risk for all-cause rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge. Commenting on the need to account for syndemics, Jack said, “Ideally, we ought to design the discharge package around medicines and other things to most approximate what the risks are that those patients have to indi-

vidualize the tools that we give them, and we are working on tools that can do that now.”

As an example of how these interactions play out, Jack discussed Project RED data showing the impact of depression on 30-day all-cause readmissions, which increased with the severity of the patient’s depression (Cancino et al., 2014). Jack and his colleagues also found that individuals with moderate to severe depression did not understand their diagnosis or their instructions as well as those with mild or no depression. The conclusions from these data, he said, is that it is important to consider factors other than health literacy when designing materials and the type of education patients will receive. He and his colleagues are now conducting a clinical trial on patients with mild or moderate depression based on their Patient Health Questionaire-9 scores.

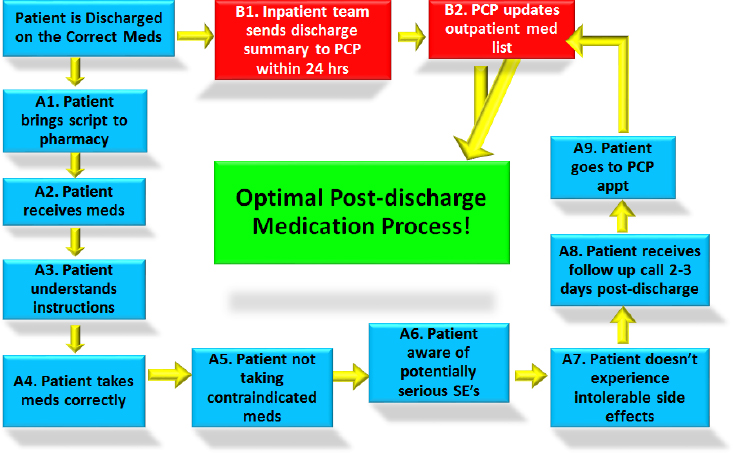

The Project RED postdischarge mediation process map (see Figure 4-8) provides a means of identifying where to measure failure models and analyze the effects of this process. For example, patients do not receive their prescriptions 2 percent of the time at his hospital. In total, about half of the patients are doing something incorrectly with the medications when questioned within 2 days of discharge. He noted that he has stories for each of the failure modes between the many steps of this process. As

NOTE: PCP = primary care provider; SE = side effect.

SOURCE: As presented by Brian Jack, November 17, 2016.

an example, one patient came to his office with materials he had received with his discharge instructions that did not conform to the Project RED requirements. Not only was it nearly illegible, but the instructions were in Latin. “We go to school for years to know what medicine is used for a diagnosis, but we go in a room and spend 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 minutes, and expect somehow magically that people are going to understand all that,” said Jack. “This workshop is such an important meeting because the tools that we need to develop are possible, and patients really deserve to know what to do, they want to know what to do, when they go home about how to care for themselves.”

Jack concluded his presentation with a brief discussion of Project ACHIEVE Qualitative Analysis, a new project funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. This 3- to 4-year project is attempting to identify what components of transition in care are important and for whom, he explained. In the study’s first year, he and his colleagues conducted 35 focus groups with 96 patients and 75 caregivers as well as 72 key informant interviews with an additional 33 patients and 39 caregivers, producing 2,000 pages of transcripts. What these activities found was that communication, anticipation of needs, and continuity of care are the three main themes for improving care transitions. Communications, for example, have to be purposeful, supportive, and collaborative, according to the patients and caregivers.

Summarizing the results of Project RED, Jack said it improves transitions of care from hospital to home, with the after-hospital care plan serving as the “active ingredient.” Project RED benefits those with low health literacy and recognizes that depressive symptoms and other comorbidities impact the ability to understand discharge instructions. Outcomes important to patients and caregivers include communication that is purposeful, supportive, and collaborative, and as a final note, he added that the syndemics of health literacy is an area in which the health literacy field needs to do more work.

PLANNING FOR NON-ENGLISH–SPEAKING PATIENTS6

By Charles Lee’s estimates, more than 30 million people in the United States do not speak English well, and this group of patients is going to be among the most likely to experience medication errors. He recounted how he used to give medication instruction sheets to some of his patients and they would nod their heads yes when he asked if they understood the

___________________

6 This section is based on the presentation by Charles Lee, president and founder of Polyglot Systems, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

instructions. “But they would get that glassy look in their eyes because they really did not understand,” said Lee. In his experience, the information he gives patients is the last thing they worry about when under the stress of being discharged and worrying about transportation and other realities of daily life. “What happens is they go home and if they cannot understand the information that is on the handout that’s given to them, they have to kind of figure things out, and I think we can do a lot better job,” said Lee.

Lee started Polyglot Systems in 2001 and with a Small Business Innovation Research grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, began to address this issue by developing medication instructions for 120 medications in 6 languages. The focus of this work is to develop a simpler, practical medication monograph, individual instructions for use, a regimen summary based on a visual daily calendar, and 3- to 5-minute video demonstrations on how to use more complex medications. “If you ever try to teach someone to use an inhaler or an eye dropper over the phone with an interpreter, you really cannot,” said Lee.

His perspective on health literacy is that it involves three phases: gathering information, understanding it, and acting on it. Given that health literacy is a personal skill and that Polyglot Systems is a small company, his goal is not to teach people how to be more health literate, but rather to leverage information technology to consolidate information, reduce its reading level, and put it in an appropriate language while focusing on key messages, removing clutter, and reducing noise. “We can give them verbal information by video, reinforced in their language, and we can include pictograms for visual referencing, particularly for dosing,” said Lee. He noted that his one criticism of FDA’s recommendation to limit medication information sheets to one page is that it restricts the ability to use large fonts that may be appropriate for elderly or visually impaired individuals.

Another emphasis of his work is to provide patients with language-appropriate materials that recommend specific actions, such as a calendar with dates and times at which patients need to take their medications. He also stressed the importance of producing materials that encourage dialogue with pharmacists and health care providers and that are individualized for each patient. Regarding this last point, Lee said that many drug monographs include information relevant to multiple indications that patients then need to sift through to find the information specific to their particular medical issue.

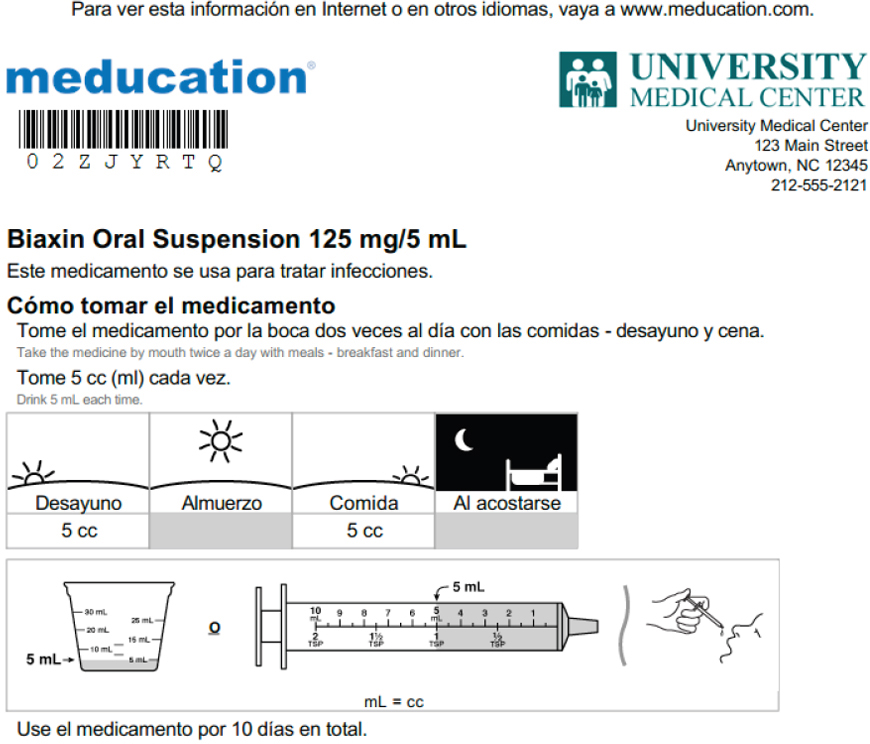

The biggest challenge in this work, said Lee, was working with consumer medication information sheets in English. “We are creating materials that people are not reading and it made no sense translating them into documents that nobody is going to read,” said Lee. “What we had to do was start with simplifying the English.” He showed one example of the company’s “Meducation” drug information sheet that illustrates how to

SOURCE: As presented by Charles Lee, November 17, 2016.

administer an oral antibiotic (see Figure 4-9). This sheet was derived from the drug monography, which does not include use instructions. He noted that the idea behind this sheet is to provide the same information, at a fifth to eighth grade level, that a good pharmacist might provide to an individual in a 2- to 3-minute conversation. “We are not trying to be a comprehensive drug reference source,” said Lee. “We are saying, ‘For you to use it safely, to know how to store it and discard it, what information do you need?’”

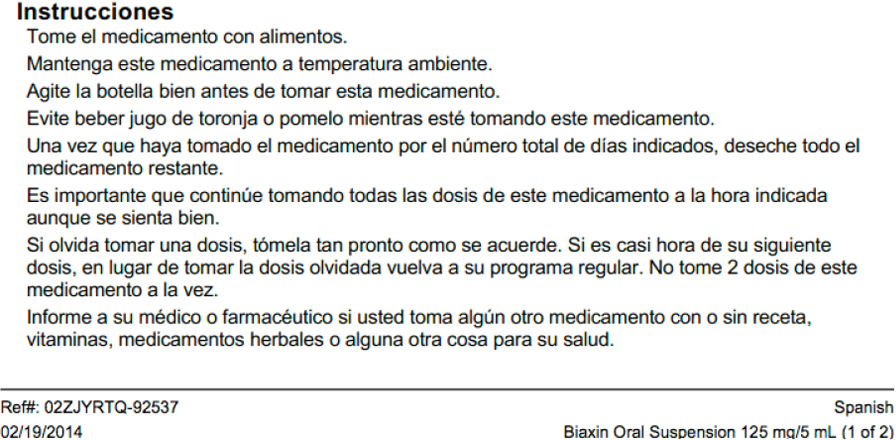

His company has also developed multilanguage discharge instructions that rely on visual drug regimen summaries for clarity (see Figure 4-10). He likened this sheet to a stacked series of uniform medication schedules that shows visually when a patient needs to take each medication throughout the day. If a medicine has a demonstration, this sheet will also include a Quick Response (QR) barcode that patients can scan using their phones to view the demonstration in the appropriate language.

Today, Polyglot Systems produces these instructional materials in more than 20 languages, including both left-to-right and right-to-left languages. Lee showed a video demonstration, accessible on a smart phone, of how

SOURCE: As presented by Charles Lee, November 17, 2016.

SOURCE: As presented by Charles Lee, November 17, 2016,

to use a Spiriva inhaler, which he said is not an easy device to use (see Figure 4-11). “What has been happening is the patient is in a rush at the pharmacy, they pick up the bag with the box in it, they go home, nobody has taught them how to use this,” said Lee. The package contains capsules that the patient is supposed to insert into a plastic inhaler and pierce to inhale the powder, but what some patients are doing is swallowing the capsules, which is the equivalent to not taking the drug at all. “Being able to have instructions they can look at once they go home is important,” said Lee.

Creating these materials requires a combination of science and art, said Lee. The science includes all of the findings of health literacy research, including what is known about reading level, visual layouts, font sizes, and the need to reinforce learnings. The art includes deciding on the key points that materials must cover as well as what information to omit. Determining reading level is also an art in that materials at the lowest grade reading level are not always better, Lee explained, because they can lose important nuances. The right reading level, he said, is one that is sufficient to convey the concept and conditions of a particular sentence. Choosing the right visual representations is also more art than science. As an example he said the graphic for food, which would be used to illustrate that a medication needs to be taken with a meal, can range from a piece of pizza to a bowl of rice depending on the cultural background of the intended recipient. “You have to think about universal representations of concepts, which is challenging,” he noted.

Label instructions, also known as SIG instructions from the Latin term for “let it be labeled,” present a number of challenges. His team has analyzed more than 7 million SIGs from pharmacies and health systems, and most of them are what Lee called free text SIGs, such as “take one tablet by mouth once daily” or “take one table per oral each day,” which are two ways of giving the same instruction. The challenge, he explained, comes from the multitude of different permutations of dose, frequency, and indication that make automated translation nearly impossible. Another challenge arises when instructions require the patient to calculate the right dose (e.g., mg to mL), when they are ambiguous, when fractions are involved—is ¼ better than 0.25? For example, the ambiguous instruction “one spray by nasal route daily,” could mean one spray in each nostril or one spray in only one nostril. The difference between these two interpretations is a doubling of the dose, explained Lee. In addition, he said, many languages do have concepts for some forms of the drug, such as a softgel or a gelcap.

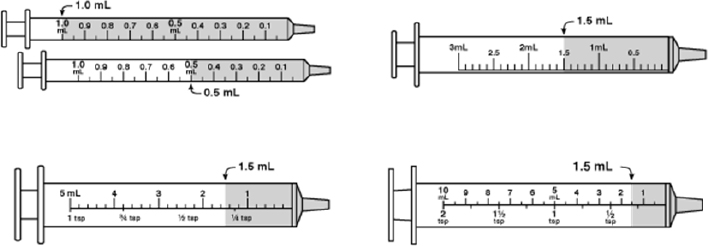

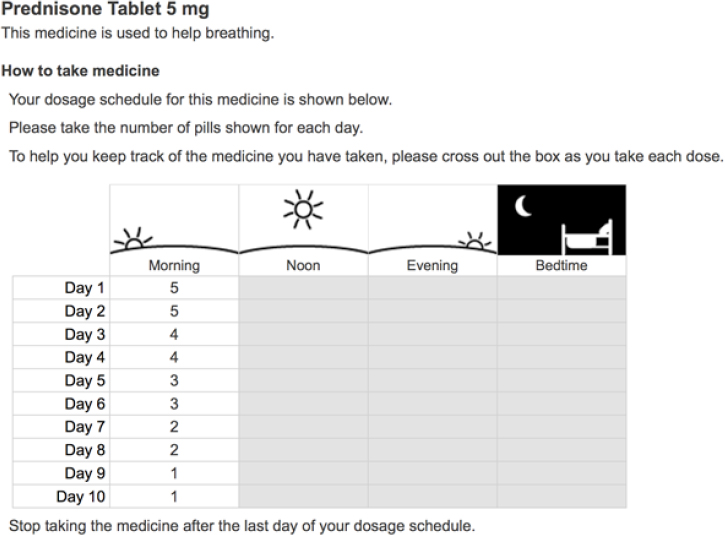

Pictograms represent a good way of presenting dosing information, particularly as dosing volumes move away from teaspoons and tablespoons to milliliters, but which type of syringe or cup to use in a picture will depend on which device the pharmacy provides to the patient (see Figure 4-12). Tapering instructions as presented today are often too complicated for many patients to follow, and Lee presented a possible alternative that can provide clarity and be easily translated into multiple languages (see Figure 4-13). Similar approaches are needed for non-daily repetitive schedules such as take one pill every other day; different doses on alternating days, such as for warfarin; or varying dosing, as is the case for insulin. All of these, said Lee in closing, are difficult for patients to comprehend and challenging to represent in English, let alone translate into other languages.

SOURCE: As presented by Charles Lee, November 17, 2016.

SOURCE: As presented by Charles Lee, November 17, 2016.

REACTOR PANEL COMMENTS7

Commenting on the four presentations from the perspective of a retail pharmacist and a member of both the Massachusetts Board of Pharmacy and the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, Donna Horn noted that Sparks was correct about the challenge of working with pharmacy software vendors, each of which has its own process for generating prescription labels. One thing she sees often with labels is that the directions are in all capital letters, which literacy research has shown makes reading and comprehension difficult. Nonetheless, many vendors sell software that only uses capital letters and getting them to change that would require them

___________________

7 This section is based on the comments of Donna Horn, director of patient safety-community pharmacy at the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, and H. Shonna Yin, associate professor of pediatrics and population health in the Departments of Pediatrics and Population Health at the New York University School of Medicine and Bellevue Hospital Center, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

to redesign their programs. “They cannot do that. They [would] have to start from scratch,” said Horn.

Label real estate presents another challenge given that state pharmacy boards require a certain amount of information on every label. She suggested that the manufacturer’s name and prescribing physician’s name could be left off a label without depriving the patient of important information. “We have to look at the information required to be on a label and ask the board of pharmacy what can be taken off to make the label easier to read,” Horn suggested.

She also commented on the NVS instrument to test an individual’s health literacy, noting that it is impossible to use at the pharmacy. “If you are at CVS or Walgreens or Walmart or Rite Aid or anywhere, no one is going to stop and ask you to do the Newest Vital Sign, even though it’s a great test,” said Horn. She added that showing the NVS to pharmacists was “really an eye opener for them.” Instead of relying on the NVS, she recommended making the information as simple as possible given that nobody will be insulted if medication information is presented to them in simple terms.

One pushback she gets from the pharmacy students she teaches at the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy is that they cannot change what the doctor wrote. For example, while the prescribing physician will write, “take one tablet twice daily,” the better instruction would be to tell the patient to take one tablet in the morning and one at night, or take one at breakfast and one at dinner to tie it to something they are going to do as part of their daily routine. The solution, she said, is to work with prescribers to teach them to write health-literate prescriptions in the way they would want the pharmacist to type that information on the label given to patients. When she has done that, it has changed prescribers’ minds about how they wrote their prescriptions.

Commenting on the fact that every state requires pharmacists to offer counseling for every new prescription, she noted Lee’s remark that the time when most patients have questions is when they start taking a medication, not when the pharmacist is handing it to them with the medication guide that they more than likely throw out when they get home. In addition, many companies have decided to provide that information the first time they fill a prescription, not with subsequent refills. “When the patient actually has a question, the information is not there.” The lesson she learned from the presentations, she said, is that it is important to understand that people have questions as they go through the journey of taking their medications.

Horn said she and her colleagues at the Institute for Safe Medication Practices developed a medication leaflet containing the 10 factors that

would allow patients to take their medications safely.8 There is a question, however, about the feasibility of implementing this list, she noted. She also wondered if the Polyglot Systems approach could create individualized labels at the pharmacy and fit into the workflow of the retail pharmacy. She remarked that the idea of putting a QR barcode on a label was interesting, but she worried about their utility for people who are not technologically knowledgeable.

Lee’s comment about getting rid of teaspoons and tablespoons is something her organization feels strongly about and is working toward eliminating and replacing with milliliters. Similarly, instructions such as “take one tablet at 10 AM on days one to four of the week,” must be replaced, she said, with “take one tablet at 10 AM on Monday and Thursday,” for example. “The more we can get that information on the prescription, then we can actually type it onto the label and things will be better for patients,” said Horn.

Shonna Yin, a pediatrician who works on designing and evaluating health literacy–informed intervention tools to improve communication between health care providers and families, including communication about medication instructions, began her comments by noting that she is working on a project funded by the National Institutes of Health to redesign medication labels for pediatric liquid medicines. She remarked that each of the presentations in this session provided solutions to important pieces of the medication safety problem, but she worries that few institutions and organizations are implementing these effective programs. “How do we get from where we are now to where we want to be, where all patients are able to receive information that is understandable?” asked Yin. “Is it necessary for us to go state by state battling to get regulations instituted?” She applauded the rigorous approach Sparks has taken in Wisconsin, assessing barriers, creating an advisory council, and getting patient feedback and input, but she questioned whether this same process should have to take place in every state. “It seems like a daunting process that will take us decades before everyone has low-literacy labels,” said Yin. “How can we better engage large chain pharmacies that span across states to try to get them to adopt and lead by example? How can we get corporate buy-in and present a business case for health literacy–informed labeling?” She wondered if there was a role for the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy to play in trying to push this issue forward and was optimistic that the upcoming labeling summit in Wisconsin could provide the impetus to push the field forward.

___________________

8 Available at http://www.consumermedsafety.org/tools-and-resources/medication-safetytools-and-resources/consumer-medsafety-lists/item/537-top-ten-things-you-must-know-aboutthe-medicine-you-are-taking (accessed March 31, 2017).

Yin noted how impressed she was with Myers’s presentation on the work Merck is doing and the company’s commitment to health literacy issues, particularly related to how it is involving patients with low health literacy in its development efforts. She wondered if FDA might be able to recommend that all pharmaceutical companies adopt such best practices or push for more standards in terms of testing drug information. “Could the FDA perhaps recommend some minimum number of low-literacy patients, for example, that medication information should be tested with?” she asked. Perhaps the agency could set a goal, she suggested, of having at least 25 percent of the individuals who are involved in testing the comprehensibility of informational materials on drugs be of low health literacy, given that more than half of the U.S. population struggles with health literacy issues. She also wondered if criteria could be established for thresholds of understanding. Referring to Merck’s ability to exceed 85 percent comprehension across different health literacy levels, Yin said, “I would love to understand more about how comprehension is tested, and how that could be adopted in other places.”

Yin also expressed her admiration for Project RED and the rigor with which Jack and his colleagues approached this problem, and demonstrated the business case of reducing readmissions. She acknowledged that many institutions are now adopting Project RED, but she wishes adoption was happening more widely. She wondered about whether Project RED could be integrated with EHR systems and expanded beyond the discharge process to include regular outpatient encounters or encounters in emergency department settings, as these are also settings where people are being sent home with prescribed medications. She had similar comments about the promise of Meducation and the slow pace of widespread adoption. “I wonder how we can encourage health systems to adopt these interventions more universally and what processes need to be in place to engage those large EHR vendors as a start to get them to adopt these kinds of interventions more broadly,” said Yin.

Commenting further on the glacial pace of adoption, she noted that despite concrete recommendations on health literacy–informed layout and content, as well as evidence-based interventions and FDA efforts to try to incorporate health literacy principles across the agency, widespread adoption of these approaches is not happening. Leveraging technology to increase adoption will be important, she said. She also pointed out that digital interoperability still has a long way to go to better coordinate the information being given out by physicians and pharmacists. “There is no cohesiveness in the messages,” she said, hoping that a consolidated portal could be used as a single source from which patients, family members, and other caregivers would receive information seamlessly.

Noting her disappointment at how often medication information is not available in a patient’s primary language and the poor quality of

translations that many patients are able to access, Yin asked if there could be an information bank that would house well-thought-out translations that any organization could use. “Why is it that every organization, every health system, every EHR vendor, every producer of patient information has to address these issues in their individual silos?” she asked. Despite the challenges, she said she is hopeful that the many stakeholders affected by this issue will be able to develop a plan to move the field forward more quickly.

DISCUSSION

Bernard Rosof opened the discussion by suggesting that wrapping a learning health system around the interventions discussed by the panelists might achieve the more rapid dissemination that Yin discussed. He also noted that because medication health literacy is a systems property, perhaps dissemination might benefit from an examination of the systems in place that might better enable dissemination. As an example, he recounted how he went to his internist, who has been his primary care physician for 15 years, during an episode of dizziness. One thing led to another, and he ended up in the hospital being seen by one specialist after another. After being discharged, he wondered if any of what he had experienced had been communicated with his internist. His question for the panelists was how it would be possible to create an integrated system that would enable the interventions discussed during this session, when even the most integrated delivery systems do not have such systems in place.

Jack replied that the situation Rosof described happens every day, and patients told similar stories when he and his colleagues were conducting focus groups at the start of Project RED. He heard stories about patients being prescribed two different medications by two clinicians for two different conditions, taking their medications properly, and then experiencing a life-threatening complication such as kidney failure resulting from drug–drug interactions. These stories, said Jack, point to the importance of better managing the ever-more-complicated transitions to, within, and from the hospital. Indeed, the goal of Project RED was to do just that for the hospital-to-home transition as a way of addressing the fact that 20 percent of patients who left Boston hospitals were having an adverse event within 20 days of discharge and that nearly 20 percent of Medicare patients are readmitted to the hospital within 30 days. He noted that the postdischarge phone call, which Project RED introduced, is not a social call, but involves the pharmacist asking the patient or caregiver to bring their medications to the phone and reviewing how and when to take them. This step, he said, is critical for identifying potential medication issues of the sort that will lead to expensive rehospitalization.

Horn raised the issue of how problems with information transfer can lead to medication errors. For example, when a patient receives a prescription at the time of discharge, they may go to the hospital pharmacy, where the pharmacist has the ability to review the patient’s EHR for any potential problems. However, if the patient decides to have that prescription filled at her local pharmacy, the pharmacist there has no way to look for any additional information. In fact, prescriptions arriving at the pharmacy electronically often need to be transcribed, creating the potential for error. “So once you get the hospital part fixed, you have to bring it back to the local pharmacy, too,” said Horn.

Sparks added that transitions from the emergency department and urgent care settings to home are also problematic. In a recent project in which he participated, he was surprised to learn that the urgent care centers belonging to a large health system in Wisconsin did not even provide discharge instructions beyond a few quick verbal instructions even when given prescriptions. “No wonder people forget what they have to do, and some of these folks end up back in the hospital,” said Sparks. He recounted one case in which a woman went to the emergency department on a Friday complaining of severe constipation and some digestive problems. She received verbal instructions to go to the drug store to get Prilosec, which she and her husband assumed was a prescription medication. When her husband went to the pharmacy, there was no prescription waiting for him to pick up, so he went home without any medication and his wife was back in the emergency department on Monday.

Cindy Brach from AHRQ asked the panelists for their thoughts on why adoption of more health-literate labels is lagging. Sparks said he believes the reason is that there is no advocacy for this to happen. He told how the pharmacists he has interviewed are all supportive of the USP standards for clearer labels and typically respond with a comment such as, “Well, why would you not want to make a medication label easier to understand?” Nonetheless, this is a back-burner issue for most pharmacists and it will remain so, he predicted, until some organization such as the National Association of State Boards of Pharmacy takes on an advocacy role on this issue.

Jack commented that when he first presented Project RED to the senior management group of his hospital, the chief financial officer wanted to know why decreasing emergency department visits and rehospitalizations was something good given the negative impact that would have on the hospital’s operating profits. “As long as we are in a fee-for-service system, even though there are these penalties, the penalties are not nearly big enough to make up for the difference in decrease in hospitalization rates significantly, so there is not much effort happening in many places,” said Jack. He also noted that many hospital administrators want to know how to decrease readmissions so that when the financial incentives to do so change, they

will be ready to implement programs such as Project RED. Jack was critical, too, of the EHR vendors who in his opinion have done little to improve the discharge instructions their systems produce even though programs are available that could be integrated into EHR systems to produce patient-centered, health-literate documents. As a result, what happens today is that nurses typically have to duplicate discharge information in the Project RED forms, an inefficient process.

Michael Wolf commented that he has been hearing this same conversation for a decade and believes that policies and a reluctance to move forward are the major barriers to adoption of the many proven approaches to producing health-literate medication information. “How much evidence base do you actually have to have before you can allow the ability to be able to go forth and launch something?” he asked. His hope is that health systems will “get out of the way,” and allow innovation to occur. “Let us not be so risk averse when we know that much of what we currently do right now, many of our practices, are harmful, and that evidence has shown that people are misinterpreting, making mistakes, and having impacts on their behaviors,” said Wolf. He then asked Lee and Jack if they have continual evaluations of their programs to enable continuous improvement. Lee said his company does do that kind of evaluation and improvement, and agreed with Jack’s comments that bottom-line issues are a barrier to widespread implementation of these systems. “To me, this is just common sense and it is the right thing to do, but it is surprising how the right thing to do does not get people to move,” said Lee. “It has got to hit their bottom line, affect their HCAHPS [Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems] scores, affect their penalties, and increase revenue, because if they just see this as work and expense, then they will not do it.” He added that getting pharmacists and physicians to buy in will require top-down and regulatory pressure.

Lee then explained how Dignity Health, the largest nonprofit hospital system in California, is integrating Polyglot Systems’ program into its Cerner EHR. This EHR tracks a patient’s preferred language upon admission, and at discharge it sends a reconciled medication list and the preferred language to Polyglot Systems, which then automatically generates the medication list in the appropriate language to be handed to the patient and used to explain the patient’s medication regimen. He noted that when San Francisco General Hospital did a pilot study with his company’s tool, the readmission rate fell from 26 percent to 8 percent.

Myers said one impediment to scaling these systems is that there are only two people in industry that she knows of—herself and Lori Hall at Eli Lilly and Company—who work full time on health literacy and medication issues. Legal issues are also a barrier in many organizations, she added.

An unidentified participant commented that a study she participated in measured 177 internal medicine patients’ understanding in three domains: their diagnosis, medication, and the procedures they experienced when being admitted. There was less than 55 percent concordance between the physicians’ documentation and the patients’ understanding, even though 45 percent of the patients had at least a college degree. To her, those data point to the implications of health literacy beyond medication issues. She then asked Jack how clinical staff find the time to do the comprehensive work it takes to increase patient understanding. Jack replied that today, the total amount of time that all clinical staff combined spends talking to patients when they go home is in the range of 6 to 8 minutes. Given that most hospitalized patients are not at peak cognitive performance when discharged, Jack said it was “magical thinking” to believe that 6 to 8 minutes is enough time for patients to understand their medications. “That is why written materials are so important and patient caregivers are so important, and why materials that both patient and the caregiver can actually understand are essential,” said Jack. His solution is to re-engineer the hospital ward, stop using procedures that are not evidence based, and start using procedures that are evidence based. He noted that he and his colleagues have created an information technology system called Louise that teaches the after-hospital care plans. In a study of 158 patients who used Louise, the patients preferred receiving information from Louise by a two-to-one margin over a doctor or a nurse. The reason the patients gave for that preference was always the same, said Jack: the doctors and nurses were too busy to spend the necessary time.

Wilma Alvarado-Little asked the panelists if they were considering the deaf and hard of hearing and the limited English-proficiency communities in their work. The honest answer, said Myers, is that the field is evolving and continuing to refine its research efforts to include these other communities. She acknowledged that Merck’s studies have not yet included anyone from the deaf community. She did note that a number of people for whom English is not their first language have participated in Merck’s health literacy studies. Sparks said that USP standards do mention dealing with people who are visually impaired or hard of hearing, but that the expense of installing a system appropriate for those individuals is too high for most pharmacies.

Jack recounted a conversation he had with someone whose hospitalized family member was blind. The patient’s room had a large sign above the bed that read, “The patient is blind,” and the nurses and other staff were terrific about explaining things verbally. However, at discharge the patient was handed a bunch of paper instructions. He noted that the Louise system is verbal and provides the patient with a CD that they can take home and listen to as needed. He added that there are companies that are developing

verbal discharge instruction tools and that the 12th element of Project RED is language assistance, which includes a tool to assess and deliver discharge information for people with various limitations.

Lee remarked that interpreters and translators have told him that they want to stay on the wards and talk to patients, not go to the pharmacy to hand-translate documents. This preference has informed his company’s approach to having discharge materials preprinted so the interpreter could review that information with the patient. “This was designed to complement oral interpretation and not replace it,” said Lee.

Jennifer Dillaha with the Arkansas Department of Health remarked that her state has a large rural population and that when patients are discharged, they can be quite far from the hospital once they return home. To address this problem, Arkansas has been looking at establishing better linkages between hospitals and local primary care physicians as well as community paramedic programs and home health care agencies. She asked the panelists if they had any experience with such efforts and how they might affect medication adherence. Lee replied that one issue is dealing with the portability of the medication lists across transitions of care. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, he explained, is working with EHR vendors on a universal or centralized up-to-date medication list. One challenge this effort is facing is the need to incorporate a feature that would allow patients and the home care nurse to provide input to the medication list. The degree to which solutions can be focused around the patient is critical to address the problem Dillaha described, said Lee.

Sparks noted that involving community paramedics is an excellent idea. He explained that he has had the opportunity to provide health literacy training to community paramedics and believes these professionals need to understand and be skilled in health literacy techniques, something that is currently the exception rather than the rule.

This page intentionally left blank.