5

Exploring the Future of Health-Literate Design

The workshop’s final panel session featured three presentations on the future of health-literate design. Daniel Morrow, chair of the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, discussed the changing ecology of medication information for patients and how Web-based information can be improved to help increase patient understanding. Heather Rennie, managing counsel in the Regulatory Legal Group at Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., then provided a lawyer’s perspective on health literacy and medication information. Next, Michael Wolf, professor of medicine and learning disease and associate division chief for research in the Division of General Internal Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, provided his view of the future of health literacy research as applied to written medication communications. An open discussion moderated by Bernard Rosof followed the three presentations.

WRITTEN MATERIALS IN THE DIGITAL SPACE1

Daniel Morrow began the first presentation of the session by reminding the participants that there is a changing ecology of health information that may have implications for the cognitive accessibility of this information,

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Daniel Morrow, chair of the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

particularly for older adults (Sharit et al., 2008). Traditionally, health information has been paper based, and for chronically ill or elderly patients, who may be taking multiple medications, the paper burden can be substantial. Today, that situation is evolving into one in which patients are getting their medication information via patient portals and other Web-based sources and are managing their medications with the help of electronic tools such as mobile phones or tablet apps. This new electronic ecology, as opposed to a written ecology, affords opportunities to increase patient access and comprehension while also constraining how individuals understand health information (Czaja et al., 2013; Taha et al., 2013, 2014).

With regard to access, Morrow explained there are challenges related to the digital divide, but also with cognitive abilities as much as technology access. The act of reading, for example, is changing, where patients are browsing electronic material more than they used to when receiving information on paper. Reading, he said, is less of a linear act when done online. People are also managing multiple documents online, perhaps guided by hyperlinks and search engines, and they have the opportunity to benefit from multimedia approaches to information dissemination. All of these factors, he said, change the requirements for comprehension substantially and place more emphasis on integrating information across multiple documents and search results.

Learning is always to some extent self-regulated, said Morrow, but it is even more so in an electronic environment. When getting information online, without having anyone present to assist them, individuals have to self-monitor whether they are truly understanding what they are reading, whether they can evaluate information to make intelligent decisions about where to go next, and how to integrate information from the multiple sources they may find in their web searches. This challenge, he said, is likely to be even greater for older adults, who may not only be less comfortable with or knowledgeable about getting information electronically, but also less cognitively able to process that information because of age-related changes in literacy and cognitive abilities (Czaja et al., 2013; Sharit et al., 2008; Taha et al., 2014).

Morrow then discussed the work he and his colleagues have been using to try to help older adults better understand both paper and electronic information. The first step, he said, is to identify the cognitive resources and abilities people need to understand health information. Next comes an analysis of how those resources and abilities influence comprehension processes and whether those processes differ in an electronic versus paper environment. These analyses can provide a firmer scientific basis for developing interventions targeted to fixing the identified problems.

This approach relies heavily on the large body of research on how aging affects cognition and how health literacy ties into that process. “For

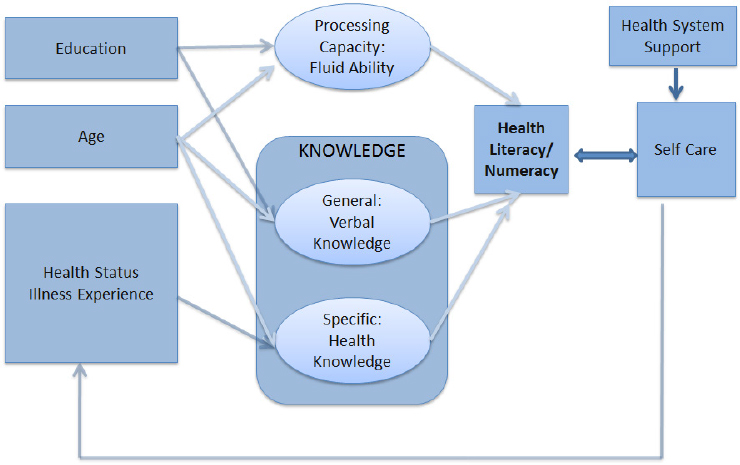

understanding the processes of comprehension, we rely on theories of text processing, language comprehension, multimedia comprehension processes, and then these same theories may help us come up with innovative solutions, design-based solutions,” Morrow said. He explained that like many researchers in the field, including Wolf and Ruth Parker, he looks at health literacy as a function involving the resources that patients bring to health care and the demands on those resources that self-care tasks such as taking medication require (see Figure 5-1). This approach leads to a focus on processing capacity and working memory processing speed in relation to aging.

To make this theoretical approach more tangible, Morrow reviewed some of the cognitive work that occurs to understand the seemingly simple instruction to take one tablet every day. First, the individual has to recognize the words. That recognition activates nodes in a mental dictionary encompassing that person’s understanding of associated concepts. That alone, however, is not sufficient for comprehension, so the next step is to put concepts together to understand the idea the sentence is conveying. In this case, that sentence is conveying an action involving a number of tablets at a specific frequency. “You put those concepts together to get a sense of the basic concept of the sentence, and that will take you some way toward comprehension, but certainly not all the way,” said Morrow. What has to

SOURCES: As presented by Daniel Morrow, November 17, 2016. From Chin et al., 2011.

happen, he explained, is for the mind to elaborate on the mental representation of those ideas with knowledge about medication and from other domains to arrive at a mental or situational model of the task at hand. This is in essence a mental simulation, Morrow said.

In the context of this model, aging is associated with reduced processing capacity, a constraint that makes those component processes harder, less efficient, and less accurate. At the same time, knowledge accumulated over a lifetime of encounters with health care systems can make those processes easier, more efficient, and more accurate. That last assumption may be less true, he added, for individuals with low health literacy compared to those with high health literacy. Morrow is now trying to decompose health literacy into age-related concepts that may interact in terms of how they influence comprehension, decision making, and self-care behavior. “The action is in the interplay of processing capacity constraints and knowledge-based facilitation,” he explained.

As an example of research results that are consistent with this model, he and his colleagues found that older adults’ ability to recall hypertension information was predicted by the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (Chin et al., 2015), an unsurprising result, he said, given that other investigators have made similar observations. Further analysis allowed them to account for much of the relationship between this health literacy measure and recall in terms of processing capacity and knowledge. The interactions among these components were also important for predicting outcomes, he added. This analysis also suggests that the ability to learn self-care information can be improved by reducing the demands of learning on processing capacity and by leveraging knowledge to support learning.

Regarding the second stage in the three-stage model—analyzing how resources influence self-care processes—Morrow explained that a large body of evidence has shown that people have a harder time recognizing longer, less familiar words, which in practical terms means that jargon represents a design challenge when creating health-literate information. Concept integration is also influenced negatively by lower health literacy resources, leading to poorer memory of information. Low health literacy also impairs an individual’s ability to elaborate concepts with knowledge, which means that poorly organized text or complex or irrelevant graphics may undermine comprehension, particularly in digital environments, said Morrow.

He concluded his presentation by discussing an intervention study in which he and his colleagues were trying to target particular comprehension processes and reduce demands on cognitive resources, thereby helping people leverage knowledge they have to improve comprehension. This intervention was a multifaceted approach to redesigning Web-based information for self-care of hypertension. This effort started with finding good examples of information about hypertension from reliable sources such as the Mayo

Clinic and the National Institutes of Health, among others. Guided by their theories and earlier findings, Morrow and his collaborators developed a comprehensive multilevel approach to improve comprehension and memory of the information from these sources. Working with medical specialists, behavioral scientists, computer scientists, and patients, they went through all of the information systematically to identify which information was needed for maximum understanding while also thinking about how to use familiar concepts to help leverage preexisting knowledge. They also focused on simplifying language and sentence structure in ways that might help older adults who have a great deal of literacy experience and on how to organize information logically rather than in the disjointed manner that was common in the materials they found in their initial search. Research Morrow had conducted in the past had shown that patients want information in a particular order and flow, so his team was careful about the titles, headers, and advance organizers it used in the materials it was creating.

Once the redesign of information was complete, Morrow’s team had 128 people read both the original and revised passages on a computer at their own pace and then summarize the main points and answer a set of questions about explicitly presented and inferred concepts. The readers had a mean age of 71 years and a high school education or less.

Test subjects remembered the revised passages more accurately, said Morrow, and required less effort to understand the same amount of information and understand both inferred and explicit concepts. Older adults with more health knowledge benefited more from the revised passages. Morrow said the most important piece of the redesign, particularly for older adults, was reorganizing content and systematically signaling how the information was going to be conveyed. Reorganizing content may also support self-regulated learning experiences, he said in closing, by making the process of remembering key concepts more efficient, thus freeing cognitive resources to evaluate comprehension in the context of online environments.

LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS IN APPLYING HEALTH LITERACY PRINCIPLES TO WRITTEN COMMUNICATION2

The health literacy world has the perception that lawyers are an obstacle to health literacy, said Heather Rennie as an introduction to her presentation. “I am here to tell you that is not the case, certainly not at Merck,” she said. “But it is important for you to understand how lawyers think and how that might be perceived as a block when you talk to lawyers

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Heather Rennie, managing counsel of the Regulatory Legal Group at Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

about health literacy.” Certainly, she acknowledged, legalese—an English term first used in 1914 to describe legal writing designed to be difficult for common people to read and understand—does conflict with the notion of health literacy.

From a lawyer’s perspective, words matter, and a lawyer’s job is to ensure that what is said will be found to mean precisely what is intended upon later scrutiny, Rennie explained. A lawyer, she added, must be aware not only of the natural meaning of the words, but also of the special meaning such words may have acquired by legal convention and by previous decisions of the courts. “What does this mean in terms of health literacy?” she asked. “Someone said earlier today to keep it simple, but whenever you get lawyers involved, they are going to want to add words because they are going to want to make sure that they have covered everything, and so sometimes that makes things difficult when you think about health literacy and prescription drug labeling.”

In contrast to what one might believe, the primary purpose of prescription drug labeling is not to give patients the information they need to take medications properly, said Rennie. Although patients may obtain useful information from prescription drug labeling, its primary purpose is to give health care professionals the information they need to prescribe the drugs appropriately, which Rennie said is an important distinction to remember. “Fundamentally, prescription drug labeling is designed first and foremost for the health care professionals who are making the prescribing decisions,” she said. Given that, she listed a number of general requirements for prescription drug labeling:

- summary of the safe and effective use of the drug

- informative and accurate

- not promotional, false, or misleading

- no implied claims or suggestions for use if evidence of safety or effectiveness is lacking

- based whenever possible on data derived from human experience

- approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Current forms of patient labeling that are part of FDA-approved prescription drug labeling include package patient inserts, which are approved by FDA and are required only for certain classes of medicines; instructions for use, also approved by FDA and required for medicines with complicated dosing instructions; and medication guides, again approved by FDA and required under certain circumstances such as when a product has serious adverse events associated with its use or when adherence to directions is crucial to the product’s effectiveness. The regulations governing prescription drug labeling encompass health literacy principles, said Rennie. Medi-

cation guides, for example, must be written in nontechnical, understandable language that is scientifically accurate, based on and not in conflict with the professional labeling for the product, and not promotional in nature.

FDA regulations also govern drug promotional materials, Rennie explained, and the information in these materials must be consistent with the approved product labeling. Promotional materials intended for physicians, for example, have to be consistent with the physician prescribing information, while consumer-directed materials must be consistent with approved patient labeling. Promotional materials must be supported by substantial evidence, balance efficacy, and risk information; must include all material information; and must not be false or misleading. As a regulatory lawyer, Rennie looks at materials that come through Merck’s Promotional Review Committee for consistency between physician prescribing information and patient product information. “In fact, I am going to look for the language to be identical,” she said.

From a health literacy standpoint, this means that if health literacy concepts are not incorporated from the start, it will be difficult for her as the regulatory attorney to become comfortable approving materials that change language appearing in the FDA-approved label. She also has to think about product liability because if a patient has an adverse event, they may want to sue the company or the prescriber. An important concept in product liability, Rennie explained, is the learned intermediary rule. In most jurisdictions, there is a defense for failure-to-warn claims that relieves a pharmaceutical company of its duty to warn the patient if the manufacturer supplying the drug provides information to the physician about the drug’s dangerous properties. What this means is that the physician acts as a learned intermediary between the manufacturer and consumer and is liable for any damages resulting from use of a drug for which the physician received notice of possible adverse events.

The rationale for this doctrine, said Rennie, is that the entire U.S. system of drug distribution is set up to place the responsibility of distribution and use on professional people. Reflecting that idea, laws and regulations prevent prescription drugs from being purchased by individuals without the advice, guidance, and consent of licensed physicians and pharmacists. “These professionals are in the best position to evaluate the warnings put out by the drug industry,” said Rennie. “As a medical expert, the prescribing physician can take into account the propensities of the drug as well as the susceptibilities of the patient, and I would argue the health literacy of the patient.”

New Jersey, Rennie noted, has an exception to this rule known as the direct-to-consumer advertising exception. In New Jersey, pharmaceutical companies that market directly to consumers can be held liable on a failure-to-warn claim. “However, even in New Jersey, if your promotional

materials disclose the risks that are included in your patient labeling—if they comply with the language in your patient product labeling—the manufacturer is discharged from liability,” said Rennie.

She noted that one could argue that the current state of product liability law is a disincentive to health literacy from a pharmaceutical company perspective, but she does not believe that to be true. “I think it is still incumbent upon pharmaceutical companies to make sure patients understand the risks and benefits of the product, but certainly the learned intermediary doctrine places the onus on the prescribing physician because it is viewed that the prescribing physician is in the best place to have the discussion with the patient and to know their particular circumstances,” said Rennie.

From a legal perspective, health literacy must be considered in product labeling, and while legal considerations may present challenges, they are not insurmountable. Timing is important and should be considered from the start of product labeling, though labels are updated if a safety issue arises in the course of postmarketing surveillance. “You can take health literacy into context then, too,” said Rennie. For products that have been on the market for a long time without any label changes, it is important to determine where the best opportunities exist to incorporate health literacy. Certainly, she said, there are no issues with reformatting labeling materials to reflect health literacy principles, nor are there legal issues with updating disease-related information to reflect new knowledge.

Rennie concluded her presentation by calling for everyone—health care professionals, the pharmaceutical industry, regulators, lawyers, and patients—to work together. “If you have lawyers in your organization and they are not at the table with you, you should bring them to the table because when the lawyers understand what you are trying to accomplish, they will help you find a solution.”

MOVING FORWARD IN WRITTEN COMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH3

Michael Wolf began the session’s final presentation by thanking Cindy Brach in her role at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for being a great advocate for much of the work discussed at this workshop. He then reminded the participants that the Institute of Medicine started thinking about standardizing medication labels in 2007

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Michael Wolf, professor of medicine and learning disease and associate division chief for research in the Division of General Internal Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

(IOM, 2008), and in the decade since that first effort, there have been some hard-fought wins. The health literacy field, he noted, has built a sizable. research-generated evidence base related to medication materials (Bailey et al., 2015; Shrank et al., 2007). FDA and U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) have become valuable contributors to this work, as have The Brookings Institution and the Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke University.

Wolf said he was excited to hear during the workshop about the continued expansion of policy reform in several states being spearheaded by state boards of pharmacy, which are working together to push through meaningful changes intended to get a better label with better information to patients. He acknowledged the support for these efforts from the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, too, as well as high-level engagement by the pharmaceutical industry involving people who are trying to find a way to do better at helping people use their medications. “I think it is important for us to recognize that we have done a great deal of good in a short period of time,” said Wolf.

Nonetheless, there are a number of issues at the intersection of health literacy and medication misuse that research has identified and that the field needs to address, said Wolf. These include

- reconciling medications;

- spacing out multidaily dosing;

- remembering to take medication, a particular problem for low health literacy patients;

- organizing and integrating complex prescription regimens; and

- problem solving, such as learning about side effects and knowing what actions to take if a dose is missed or a medication is misused.

Wolf then discussed the findings from a recent systematic review of interventions to improve medication information for low health literacy populations (Wali et al., 2016). This review of some 50 published papers examined interventions in six categories—written information, visual information, audible or verbal information, label information, reminder systems, and education programs and services. While the majority of the evidence in the reviewed studies was “mediocre,” according to Wolf, about half to two-thirds of the studies in each of the six categories were successful at improving comprehension, with a few interventions improving medication adherence or behavioral outcomes. The most important finding from this review, however, was that the best interventions were not singular in their approach, but were supported by tailored, personalized materials from other sources. For example, a patient receiving verbal counseling would also receive written materials specific to the individual that supported the spoken message. In addition, interventions that targeted health systems to

ease navigation and simplify access to content also were the most successful, explained Wolf.

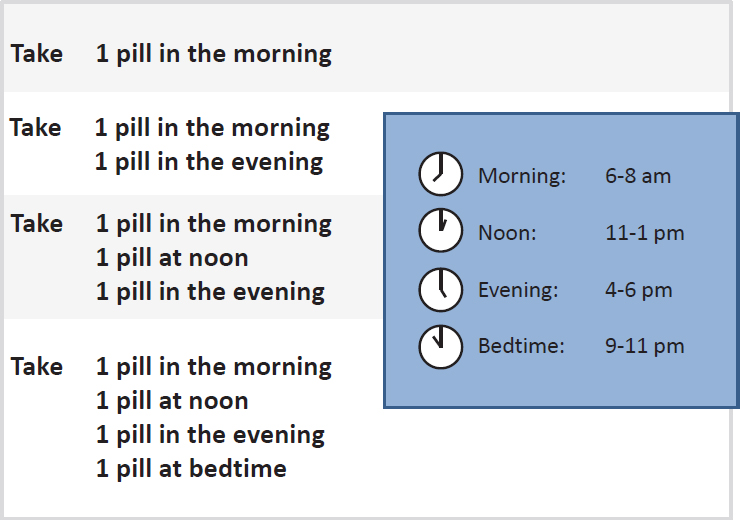

A decade ago, Wolf continued, he and colleagues Terry Davis, Ruth Parker, and Alastair Wood proposed what would eventually be called the Universal Medication Schedule (UMS). The basic idea of the UMS (see Figure 5-2), he explained, was to write instructions more explicitly using a construct that individuals at any level of health literacy would understand. A recently published study (Wolf et al., 2016), funded by AHRQ, showed that the UMS had a modest effect on improving adherence among the general population, but had a more substantial effect on individuals with limited literacy skills who were taking more complex drug regimens or who had medications prescribed for multidaily dosing. Given the low cost of implementing the UMS on written instructions, he predicted the benefit-to-cost ratio for the UMS would be large.

The evidence generated so far on the effectiveness of various interventions on medication adherence and safe use has produced a few important takeaways, said Wolf. The first is that plain language in written prescription drug labeling alone has a limited ability to reduce disparities among individuals with low literacy. “That is just a statement,” said Wolf. “It

SOURCE: As presented by Michael Wolf, November 16, 2017.

does not mean that we should not be doing it.” What he and his colleagues have found, though, is that any health literacy intervention, whether it is on auxiliary warning labels, prescription dosing instructions, or medication guides, does improve outcome significantly across all levels of health literacy (Sahm et al., 2012; Wolf et al., 2010, 2011, 2014). “The disparity between the highest functioning literate patients and those with the lowest literacy skills does not shrink,” Wolf explained. “You are not going to get the benefit you need using written materials if you cannot read very well. It just makes sense.”

Another takeaway from the accumulated body of evidence is that variable content for prescription medications still exists. “We need to get past this,” said Wolf. “It is just an amazing thing that we cannot find a way to have standardized content about what needs to be known about a particular medication because then we can start having the conversation about how to improve it and then how best to disseminate it.” The fact that educational materials vary so dramatically, he added, is a major hindrance to moving forward with evidence-based interventions. In addition, despite a decade of work stressing the importance of the relationship between provider and patient, spoken counseling from physicians, nurses, and pharmacists remains infrequent and inadequate. Multifaceted communications strategies that engage providers and that are co-developed with patients are needed to make truly meaningful changes in how patients learn about and use their medications, said Wolf.

Moving forward, Wolf said the field needs to set standards that go beyond written materials. He acknowledged that USP has done a good job establishing and promoting standards for written materials. Now is the time to look closely at how those standards translate into how the field develops, designs, and disseminates digital tools that communicate information and support patients’ behaviors with their medications, he said. He noted there is an expansive literature that identifies ways to optimize written health materials (Jacobson and Parker, 2014) as well as evidence on how to design robust multimedia materials (Mayer, 2005). There is even a tool that AHRQ created, the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT),4 that those who develop materials can use to assess understandability and action-ability. However, he added, despite this body of literature and tools such as PEMAT, recommended principles are ignored more often than not.

Commenting on how he wishes the discussion could move beyond what font size to use when creating written materials, Wolf said that bridging the many divides is going to be very challenging going forward given how the system of health care delivery in the United States is “one of our great-

___________________

4 See http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/self-mgmt/pemat/index.html (accessed March 31, 2017).

est adversaries in terms of trying to give people good information about their medicines.” Today, for example, even coordinating communications between the pharmacist and physician is difficult, and interventions aimed at addressing that problem have not had much success. The lack of interoperability among electronic health records (EHRs) and pharmacy labeling systems exacerbates this problem, said Wolf. Except for the rare health system with embedded pharmacies, it is difficult to create interventions in which the physician at the prescribing end and pharmacist at the dispensing end can reinforce each other’s messages and provide adequate counseling to patients.

Part of the solution, he proposed, is that the EHR might serve as the focal point for such coordination. In fact, he and his colleagues are working in partnership with Walgreens and UnitedHealthcare to examine how it may be possible to leverage technology to allow pharmacists to provide extensive support to patients, with the key being that pharmacists will need to have access to a patient’s medication list and their EHR.

Moving beyond written information, Wolf mentioned a recent paper that reviewed 16 trials targeting medication adherence using mobile phone text reminders (Thakkar et al., 2016). A meta-analysis of these 16 studies showed that a simple ongoing text reminder service produced an average two-fold increase in medication adherence. He said that while many technology platforms might have the potential to improve medication adherence and safety, most are not matched to patient needs, and these modalities may not match patient preferences. In 2014, he and his colleagues surveyed user reviews of the approximately 400 mobile phone apps for medication self-management and found that their design was largely not patient centered (Bailey et al., 2014). In fact, he said, few of these apps were designed with input from patients and so perhaps it is not surprising they do not address the barriers patients face in using their medications properly.

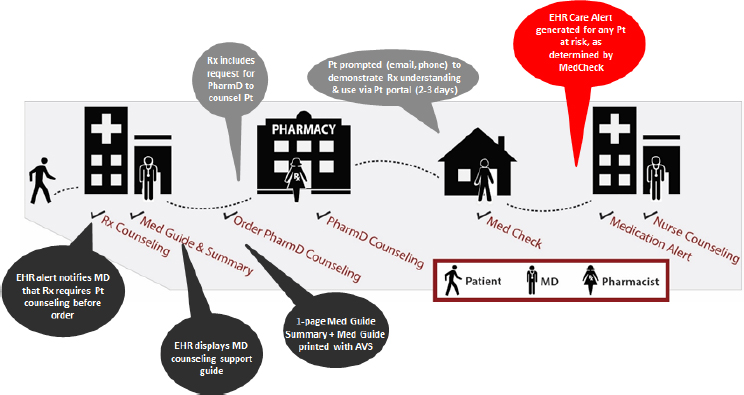

Wolf concluded his presentation with a brief discussion of a system he and his collaborators on working on with Eli Lilly and Company that can use the EHR to create multiple points of providing information to patients about their medications (see Figure 5-3). For example, this system would use the EHR to prompt physicians with best practice alerts when they write a prescription and provide counseling advice on what they can say to their patients. The system would also automatically generate a one-page medication guide summary that would include a link to the medication order and an after-visit summary. The patient would receive automated prompts via email or phone that would ask them to use their patient portal to report on how they are doing with medication, if they are having problems, if they have missed any doses, or if they have experienced any side effects. The system would also generate an EHR care alert for any patient at risk as determined by that medication check.

NOTE: AVS = after visit summary; EHR = electronic health record; MD = medical doctor; PharmD = doctor of pharmacy; Pt = patient; Rx = prescription.

SOURCE: As presented by Michael Wolf, November 17, 2016.

In closing, Wolf said there are many good interventions and innovations available, as well as some that are horrible, but the important point is to test these interventions and use the ones supported by evidence. “We need to get out of the way of ourselves and just start doing something, to know that we can evaluate it and if it does not work, we can learn something from it,” said Wolf. “I do not think we are going to be doing something worse than what we are already doing right now.”

DISCUSSION

Brach opened the discussion by asking Rennie to clarify how manufacturers can rewrite and change FDA-approved labeling to reflect focus group assessments given that FDA-approved language is sacrosanct. Rennie replied that the testing and revision process happens before the sponsor submits labeling language to FDA. The testing and revision process is built into the time line that her company, and she supposed every other pharmaceutical company, develops for the drug approval process, and it starts well before FDA is ready to grant approval for a new medication.

Marin Allen from the National Institutes of Health commented on the need for the manufacturer of a drug, who knows more about it than any-

one, to share responsibility with physicians to ensure that patients understand how best to take their medications. In her opinion, the onus for doing so should not rest solely with physicians. She also remarked that patients are being confused by the disclaimer messages that accompany television drug advertising, which she said she understands fulfills a legal requirement, but does little to tell patients what a given medication will do for them. Rennie responded to Marin’s call for the pharmaceutical industry to try to address these two concerns by noting that those very concerns drive Merck’s efforts to make health literacy a requirement. “We do think that the physician’s time is limited and not everyone out there has an incentive to educate the patients, and so when we have a new product coming on board, and for the products that we do have, we take that role seriously,” said Rennie. “We all want to do what’s in the best interest for patients, and certainly from a legal perspective, I want to make sure that patients have all the information that they need to take the product safely.”

Rosof asked the panelists to comment on what they believe would be valuable to the roundtable in thinking about health-literate design going forward, and in doing so, to be innovative. Morrow replied that he thinks it important to help people not only find information, but also evaluate and integrate information across multiple documents in an online environment. “We know, at least anecdotally, that people are being nudged all the time by the way websites are designed to go elsewhere, and they may not remember to come back,” he said. A useful step, he noted, may be to think about this problem in terms of the way animals forage for food, where they are constantly adapting to the ecosystem in terms of where to look. In that respect, there are theories of information foraging that can help people evaluate information and make on-the-fly assessments about whether they have got the information they needed to answer their questions or if they need to continue their search elsewhere. Such theories may be particularly useful for helping older adults who spend too much time reading text online, whereas younger adults tend to be better information foragers and are better able to remember more information across multiple information sources. “I think there is interesting work in computer science that embraces the idea of ecology of information and how it is transforming with the new media,” said Morrow.

Rennie said she has observed over the past decade that there has been a move to put more information into patient medication guides and physician prescribing information. “That has had the effect of making patients overwhelmed, quite frankly,” said Rennie. Instead of listing every possible side effect, perhaps a better way to go would be to list the most common ones and then include a statement as simple as “If anything changes, make sure you call your doctor because it could be a side effect.” In her opinion, that type of discrimination among which side effects to list would go a long

way toward helping patients and alerting them to pay attention to how they react when taking a prescription drug. She also commented on the message she heard that the pharmaceutical industry does not do a good enough job telling patients why it is important for them to take their medications. “It used to be that pharmaceutical companies did more of that,” she said, noting that companies do less of that now in response to warning letters from FDA regarding the need to have outcomes data to be able to discuss outcomes of the disease. “I think we need to figure out how we can fill that void to let patients know not only here is the condition, but why it is critically important if their physician has prescribed this medication to take it so that you can hopefully stave off this sort of bad outcomes in the future,” said Rennie.

Giving context to his comments, Wolf said what he cares about is helping patients get the optimal benefit of the medications they are prescribed, to be able to take them, minimize any harm associated with them, and also be properly vigilant so they can problem solve and seek care if necessary. From that perspective, he said many things can help patients, such as disseminating good content through patient portals, but implementing these types of interventions means overcoming barriers by engaging more with providers. “Whether that is a care coordinator, a pharmacist, or an allied health care provider, we need some way to have ongoing relations with patients between encounters, and maybe even start by focusing on those who are at greatest risk, such as those patients who have a lot of medications to take,” said Wolf. That is where he hopes the roundtable can be creative in thinking about how health care is being redesigned and how to create more linkages for knowledge exchange in a health-literate manner that engages patients in their own care and supports behaviors that encourage them to seek information and problem solve about their medications.

Jennifer Dillaha with the Arkansas Department of Health commented that the growing number of older adults who are not likely to improve their own health literacy skills places a burden on an increasing number of families to gain the skills needed to understand proper medication use. She asked Morrow if the Internet work his group has conducted could be applied to patient portals, which is where many family members and other caregivers will go to get the information they need. Morrow replied that he has a project under way that is being driven, in part, by his frustration about using his patient portal to understand clinical test results. “It is abundantly clear that the best practices that we have been talking about today are not being used routinely in terms of designing the information that is on patient portals,” said Morrow. This project is attempting to present information in a way that will enable older adults to understand the risk implications of the numeric information from test results, such as cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Relying heavily on graphical represen-

tations, he and his team are moving toward developing a conversational agent interface that would provide an interaction with a virtual physician who can provide high-level commentary on the accompanying graphics. “The idea is not to do an end run around face-to-face communication with your doctor, but to help bridge that gap,” said Morrow. In some respects, he added, this type of system would provide patient decision support in the way that an EHR can provide clinical decision support to the physician.

Catina O’Leary from Health Literacy Media noted that despite all of the good interventions that have been developed, nothing seems to disrupt the system in a way that enables those interventions to gain much of a foothold and then spread in the nation’s health care systems. Wolf agreed with that assessment and said that like O’Leary, he is tired of coming to meetings and hearing the same things that he has been hearing for the past 15 years. “I am sick of going to multiple meetings at different agencies and feeling like I am having the same conversation over again,” said Wolf. He added that his frustration over the lack of progress is one reason why he and his colleagues are working to use the EHR as the focus of a system that will automatically alert physicians about the need to provide more information to patients about their medications and to provide that information in plain language the physician can use.

One component of this system that he is working on now is a way of tracking how often physicians provide the necessary information and creating a metric that could serve as a quality indicator and give feedback to the physician. Wolf added, though, that patients need to be accountable, too, particularly those who are taking multiple medications. Physicians could ask patients to check into their portals every few weeks and report on how they are doing with their medications by answering a short questionnaire, for example.

James Duhig from AbbVie Inc. noted that his company has a program for one of its major products that has several hundred nurses trained in cultural competencies who can provide health-literate information on this product. The challenge, he said, is to reproduce that type of support system for products that do not generate billions of dollars in revenue. He then asked if the goal of the health literacy community is to continue being an add-on, or if the goal is to make health literacy an integral component of medication outcomes. Wolf said he is encouraged by the way in which health literacy is now seen as part of appreciating the user experience and that the field is starting to benefit from human factors research, cognitive psychology, and efforts to design learning environments.

In Wolf’s opinion, the health literacy field needs to make sure that in this time of a growing emphasis on patient engagement that health literacy is at the table for those conversations. Health literacy, he said, needs to become active in organizations such as the American Public Health Asso-

ciation, the Society of General Internal Medicine, and AcademyHealth, and to have representation in the special interest groups advocating for more patient engagement. The health literacy field needs to do a better job conveying that health literacy is more than just putting complex ideas into plan language. “We are a behavioral science, not just an information science,” said Wolf. In his opinion, health literacy needs to be seen as a field focused on using information better to engage patients to make them care more about their own health.

Morrow said Wolf’s comments reminded him of the discussions that used to be held about how to infuse human factors into organizations so that they are “breathing the concept” and that it becomes an embedded competency. FDA, he said, has led the charge on this front, and human factors is gradually becoming an inherent part of the process at many organizations. He noted that achieving the same status for health literacy would be helped by the ongoing work on health-literate organizations and how they function. Rennie added that one important area in which health literacy needs to become an integral part of the design process is in the social media world given the central role social media plays for younger adults when they look for information on what might be ailing them. “They do not call a health care provider, they go onto Google and try to figure it out,” said Rennie. It is imperative, then, to determine how to help ensure that people going to social media and the Internet for information are getting accurate, complete, and not misleading information. The industry has not yet figured out the best way to use social media, she concluded.

This page intentionally left blank.