1

Introduction

Food and nutrition policy in the United States and Canada emanates from a variety of activities, including conducting dietary intake surveillance and monitoring, funding and conducting research and education, and reviewing the science. These activities constitute the backbone of developing population-based dietary intake recommendations as well as designing food and nutrition assistance programs for vulnerable populations, with the ultimate goal of improving the nutrition and health of the population. In the United States, the first efforts to establish the science of nutrition date from 1893 when Congress authorized the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to conduct research on agriculture and human nutrition, and this coincided with a period when nutrition deficiency diseases, such as scurvy and beriberi, were being described (HHS, 1988).

Murphy et al. recently summarized the “long road leading to the Dietary Reference Intakes for the United States and Canada” (Murphy et al., 2016). Briefly, the first Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) were developed by the National Academy of Sciences’ Food and Nutrition Board at the request of the National Defense Advisory Commission and adopted at the National Nutrition Conference in 1941. The goal was to assist with World War II food relief efforts where needed. In Canada, a similar process to establish nutrition standards had started in 1938. For the next 40 years, RDAs were periodically reviewed and updated. As knowledge about nutrition and health steadily expanded, research about the contribution of nutrition to noncommunicable chronic diseases began to emerge and was summarized in a landmark report, Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease, which was published by the

National Academy of Sciences in 1989 (NRC, 1989). In addition, the RDAs were being reconsidered as their uses expanded into new arenas. The uses and misuses of RDAs in fortification programs or supplemental food packages for targeted subgroups, for which estimation of levels of inadequacy is needed, prompted exploration of new reference values and a new framework. An approach to identify potential adverse effects of excessive nutrient intake was also important for the regulation of food fortification by federal agencies. In 1983, the Recommended Nutrient Intakes replaced the RDAs in Canada, and in the mid-1990s, the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) replaced the RDAs in the United States.

The publication of the DRIs signified a change in paradigm that was intended partly to allow for better understanding the dietary intakes of populations. As such, DRIs were defined as a set of six reference values related to both adequate intakes and upper levels of intakes.1 DRIs are specified on the basis of age, sex, and life-stage and cover more than 40 nutrients and food substances. DRIs have been established by different committees of experts (DRI committees) under the auspices of the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The most recent report is an update of the 1997 DRIs for calcium and vitamin D (IOM, 2011b).

Since 1997, DRIs have been intended to serve as a roadmap for assessing intake and planning diets for individuals and groups, and to provide the basis for food guidelines in both the United States and Canada. For example, health professionals use DRIs to guide individual nutrition decision-making (Murphy et al., 2016). DRIs also are used in the development of nutrition policy, notably for the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Advisory Committee (DGAC) used the DRI values as evidence to estimate which nutrients were over- and under-consumed, based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data (USDA and HHS, 2015). Data on over- and under-consumption, combined with nutritional biomarker status data and information about the relationship with chronic disease, were used to identify nutrients of public health concern (e.g., sodium and calcium). The DGAC also used the DRIs to determine whether USDA food patterns are adequate to meet nutrient requirements. Similarly, the Canadian Food Guide promulgates food patterns based on the DRIs. Food patterns2 are significant in the

___________________

1 See definitions in Chapter 2 (see Box 2-1) and all the values and related reports in http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Nutrition/SummaryDRIs/DRI-Tables.aspx.

2 Developing food patterns encompasses an iterative process with the following steps: (1) identifying appropriate energy levels for the patterns, (2) identifying nutritional goals for the patterns, (3) establishing food groupings, (4) determining the amounts of nutrients that would be obtained by consuming various foods within each group, and (5) evaluating nutrient levels in each pattern against nutritional goals (USDA and HHS, 2015).

sense that they identify patterns of eating that would meet known nutrient needs, balance intake from various food groups, and can be used as the basis for nutrition communication to the general population (e.g., the Food Guide Pyramid; MyPlate).

Another important use of DRIs is the Nutrition Facts Panel that appears on packaged food products, which uses the term “Daily Value.” The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) developed Daily Values based on DRIs to inform consumers about the percentage that a serving of a particular food contributes to the requirement for that nutrient. Health Canada took a similar approach to informing consumers with nutrition facts based on DRIs. DRIs also are used by food companies in making nutrient claims (e.g., “free,” “high,” and “low”) about a product’s nutritive value (IOM, 2003). Under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) of 1990 (21 U.S.C. § 343), the U.S. government sets strict rules and definitions that a product must meet to make a nutrient claim. For example, “low in sodium” means a product must contain 140 milligrams of sodium or less per serving (IOM, 2003). Other important uses for DRIs include dietary intake surveillance of populations, government food assistance programs, nationwide health programs (e.g., Healthy People 2020), and food planning for military personnel. For example, DRIs are the basis for the Military RDAs and Military DRIs (MDRIs) through Army Regulation (AR) 40-25. These MDRIs have been used to not only plan meals at military installations but also to plan the Meals Ready-to-Eat (MREs), Survival Rations, and other special rations used in the field (IOM, 1994, 2006a,b).

RATIONALE FOR SETTING CHRONIC DISEASE DIETARY REFERENCE INTAKES

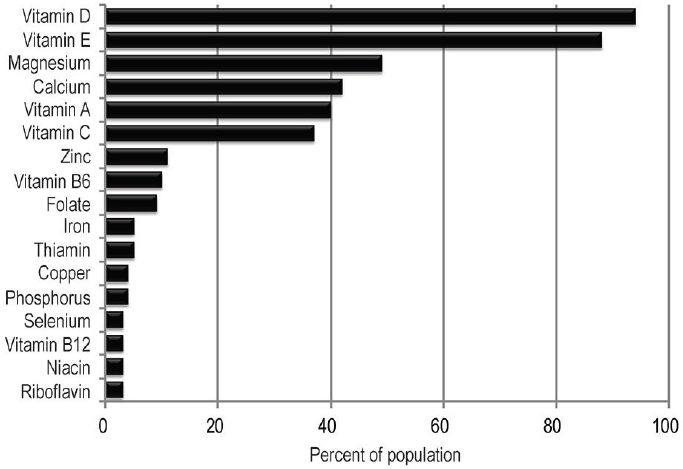

Although nutrient deficiencies are still widespread at a global level, they are less common in the western world and the United States in particular. Even so, in the United States, some essential nutrients are consumed at levels below adequacy (e.g., vitamins A, E, B6, and C), and such nutrition deficiencies have persisted from the 1970s to the 1990s for most age and racial/ethnic groups (CDC, 2012). Figure 1-1 shows the percentage of the U.S. population with usual intakes below the Estimated Average Requirement3 (EAR). These percentages, derived from NHANES 2007-2010 data, estimate dietary nutrient inadequacy. Prevalence estimates of nutrition deficiencies (based on biomarker concentrations that indicate a risk of disease

___________________

3 Estimated Average Requirement is the average daily nutrient intake observed in an apparently healthy life-stage group. It is based on experimentally derived intake levels or observations of mean nutrient intakes by a group of apparently healthy people who are maintaining a defined criterion of adequacy.

SOURCE: USDA and HHS, 2015 (Figure D1.1).

rather than on estimates of dietary nutrient inadequacy) among people who live in the United States have not been collected recently, but data from NHANES 2003-2006 have found low levels of deficiency (from 10.5 percent to <1.0 percent). Likewise, data from a 2004 survey show that the majority of Canadians consumed adequate amounts of micronutrients and that the highest prevalence of inadequacy were for magnesium, calcium, vitamin A, and vitamin D (Health Canada, 2012). Possible reasons for this positive outlook are ongoing efforts in enrichment, fortification, and other improvements in the food supply. For example, thanks to fortification policies in the United States, the prevalence of folate deficiency has dropped among women of childbearing age from 10 to 12 percent to less than 1 percent (CDC, 2012).

Today, an even more challenging health problem than nutrient deficiency diseases is chronic diseases.4 It is estimated that chronic diseases are responsible for 70 percent of all deaths globally. Of these deaths, 82 per-

___________________

4 A chronic disease is “a culmination of a series of pathogenic processes in response to internal or external stimuli over time that results in a clinical diagnosis/ailment and health outcomes” (e.g., diabetes) (IOM, 2010, p. 23).

cent are due to cardiovascular diseases, cancers, respiratory diseases, and diabetes (WHO, 2014). In the United States, half of all adults have at least one chronic health condition such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer and others (Ward et al., 2014). Five of the top 10 causes of death in 2010 were chronic diseases (CDC, 2014). The extent to which specific nutrients or other food substances (NOFSs) contribute to the development of chronic diseases is uncertain, mostly because the etiology of chronic disease is complex (i.e., the result of environment and genetic factors and their interactions) and they develop over long periods of time. However, a robust scientific literature suggests that the contribution of nutrients and diet to the prevention of chronic diseases is important and that many chronic diseases could be prevented, delayed, or alleviated through lifestyle factors, such as changes in diet and exercise (CDC, 2017) and that poor dietary patterns, overconsumption of calories, and physical inactivity are contributors to preventable chronic diseases (USDA and HHS, 2015).

Given the growing understanding of the role of nutrition in chronic disease, a new concept evolved that NOFSs could serve not only to prevent deficiency diseases and toxicity but also to help ameliorate chronic diseases. For example, the evidence suggests that excess intake of some nutrients contributes to some chronic diseases (e.g., sodium and cardiovascular disease), whereas intake of other nutrients that greatly exceed current reference values may help prevent chronic diseases (e.g., omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease). Past DRI committees had begun to deliberate about including chronic disease in setting DRIs—and did so for a few nutrients (see Chapter 2)—even though the definitions of DRIs were conceived solely with the goals of reaching nutrient adequacy and avoiding toxicity. As more experience was accumulated and public discussions took place, the nutrition community (e.g., researchers and policymakers) recognized that considering chronic diseases raised new challenges and questions for DRI committees, requiring a special focus and specifically oriented guidance. From there, a consensus emerged that a common understanding of the challenges was needed, as were recommendations and guiding principles to drive the activities and approaches of future DRI committees.

In response, in 2015, a multidisciplinary working group sponsored by the Canadian and U.S. government DRI steering committees convened to identify key scientific challenges encountered in the use of chronic disease endpoints to establish DRI values. Their report, Options for Basing Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) on Chronic Disease: Report from a Joint US-/ Canadian-Sponsored Working Group (i.e., the Options Report) (Yetley et al., 2017), outlined and proposed ways to address conceptual and methodological challenges related to three aspects of the work of future DRI committees: (1) What are acceptable levels of confidence that the relationship

between an NOFS and a chronic disease is causal?, (2) If a causal relationship exists, what are acceptable levels of confidence in the data to establish an intake-response relationship and what are approaches for identifying and characterizing the intake-response relationship and, if appropriate, to recommend DRIs?, and (3) What should be the organizational process for recommending chronic disease DRIs?

STATEMENT OF TASK

The statement of task for the current study (see Box 1-1) requests that the committee assess the options presented in the Options Report and determine guiding principles for including chronic disease endpoints for food substances5 that will be used by future National Academies committees in establishing Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs). The report uses the term “nutrient or food substance” (NOFS) throughout to reflect the totality of this definition.

The Options Report presented several issues and approaches that this committee was asked to consider in making its recommendations. One issue was whether to continue incorporating chronic disease endpoints into the existing DRI development process or to develop a separate, complementary process. Another issue related to whether the DRI process for considering chronic disease endpoints would continue to consider, separately, food substances that may be interrelated in their apparent causal relationship to a chronic disease or be clustered according to their apparent causal relationships to a single chronic disease. The Options Report also addressed the circumstances under which surrogate markers of disease could be used in place of endpoints based on actual disease incidence, and the level of certainty required for a judgment that an observed association is a causal relationship. When a causal relationship has been identified with sufficient confidence specific intake-response relationships need to be defined, and the Options Report laid out six issues where recommendations and guiding principles were needed: (1) the acceptable level of confidence (i.e., low, moderate, or high) in the intake-response relationship that would be used to set reference values, (2) the types of reference values to be established to indicate benefit (i.e., whether similar to the current DRI approaches or based on ranges), (3) types of reference values used to indicate harm (e.g., whether using the current approach to identifying Tolerable Upper Intake Levels [ULs] or developing a new approach), (4) how to address potential overlap between benefits and harms (i.e., whether to avoid any overlap, establish criteria based on degree of risk reduction, or describe

___________________

5 Food substances are nutrients that are essential or conditionally essential, energy nutrients, or other naturally occurring bioactive food components. (Yetley et al., 2017, p. 253S).

the evidence to support user-based decisions), (5) selecting indicators for specifying intake-response relationships (i.e., types of indicators, whether single or multiple, and for single or multiple diseases), and (6) under what circumstances to allow extrapolation for population groups other than those studied (i.e., to similar populations for which the availability of evidence is limited).

APPROACH OF THE COMMITTEE

An ad hoc committee of 12 experts and 1 consultant was selected to respond to the statement of task. Experts were drawn from a broad range of disciplines, including human nutrition, toxicology, biostatistics, major diet-related chronic diseases, preventive medicine, study quality assessment, research methodology, epidemiology, and use of DRIs. Three of the members were among the authors of the Options Report.

During the course of the study, one public meeting and one public

workshop were held to gather data and information in areas requested by the committee, including clarifications from the sponsors related to the statement of task (see Appendix A). Based partly on those clarifications, the committee offers the following key considerations related to interpreting the statement of task.

DRI Framework and Process

The most recent DRI report for vitamin D and calcium (IOM, 2011b) adopted the concept of risk assessment and its components (hazard identification, hazard characterization, intake assessment, and risk characterization) as the organizing framework applicable to the activities in establishing EARs and ULs (see Annex to this chapter for the description of each step as it applies to establishing DRIs). The 2011 report states that adopting risk assessment as a common paradigm for EARs and ULs, and in general for any indicator of interest, will result in a process that is flexible, transparent, and suitable for making decisions related to DRIs. Following this concept and the statement of task (see Box 1-1, item 3), the committee addressed two framework components: (1) indicator review and selection (hazard identification) and (2) intake-response assessment and specification of reference values (hazard characterization).

To fulfill its task, the committee developed recommendations and guiding principles around these two framework components. First, the committee developed recommendations that specifically answer the task of selecting options from the Options Report. Because each NOFS, chronic disease, and their relationships will present idiosyncrasies, the recommendations will be of value only if they are broad and flexible. The guiding principles, in contrast, are meant as a foundation for a scientifically credible chronic disease DRI process. Although recommendations about integrating chronic disease as a consideration in setting DRIs should be revisited in the future as more practice and knowledge are acquired, the guiding principles are meant to withstand scientific and methodological advances that will occur in the future.

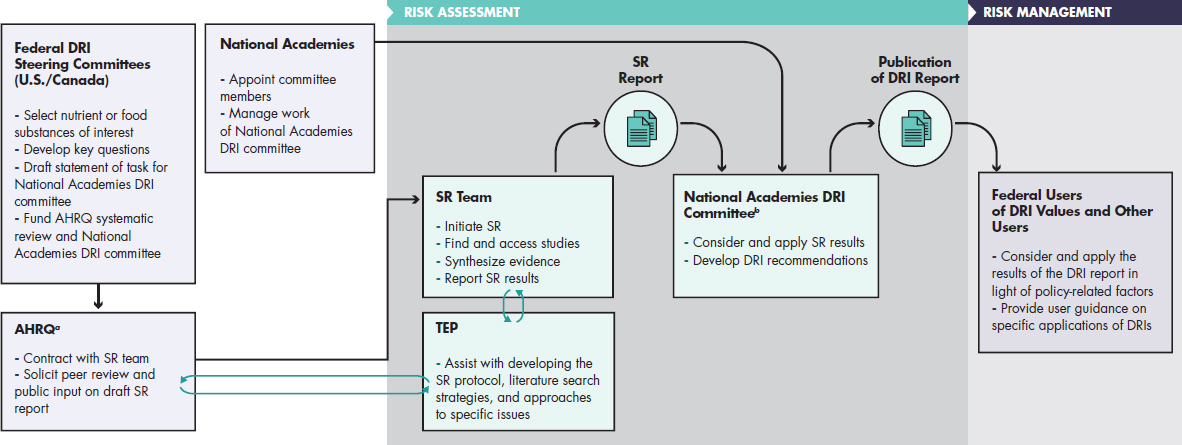

The intent of this report is not to change the core DRI process but to provide a degree of consistency and transparency in the approach to making decisions when the process of considering chronic disease endpoints for establishing DRIs is conducted. Therefore, the committee offered its recommendations and guiding principles in the context of the process shown in Figure 1-2, which illustrates actors and selected tasks. Figure 1-2, which is patterned after the general process of guideline review (IOM, 2011a,c), shows that development of DRIs requires the coordinated work of groups of individuals charged with risk assessment and risk management tasks. For example, the U.S. and Canadian DRI steering committees will consider

NOTES: AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; DRI = Dietary Reference Intake; SR = systematic review; TEP = Technical Expert Panel. a The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality is listed here as the agency that, in the current DRI process, has been responsible for the systematic review aspects of DRI development. b National Academies DRI committees are convened by and positioned with the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and operate under the National Academies study committee guidelines, which include an external peer review process of the draft DRI report.

SOURCE: Adapted from IOM, 2011a,c; Taylor, 2008.

many factors when selecting nutrients of interest and formulating statements of task for DRI committees. At the end of the DRI process, federal users of DRI values and other users may consider and apply DRIs in light of policy-related factors in various ways. Although DRI committees should be sensitive to risk management considerations, risk management decisions are not the purview of DRI committees. Also, as shown in Figure 1-2, the committee suggests continuation of the practice started with the 2011 DRIs for calcium and vitamin D, in which formal systematic reviews were conducted by an outside contractor (e.g., an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-based Practice Center) before the formation of the DRI committee. The systematic reviews results were then used by the DRI committee to determine what DRIs were appropriate and to recommend specific levels or ranges. As shown in the figure, systematic reviews designed to inform health-related recommendations, such as DRIs, involve many steps that, for a high-quality result, need to be conducted according to well-established methodologic standards with attention to the most recent updates in these standards (see, e.g., http://handbook.cochrane.org, accessed July 22, 2017, and IOM, 2011c). It includes having guidance from a technical expert advisory committee, an opportunity for peer-review and public comment, and publication of the final systematic review report. The quality of the initial systematic review is critical for an effective DRI committee process. Once initiated, the DRI process may involve additional systematic reviews, as determined by the committee.

In general, guideline development processes require that systematic reviews are formulated, conducted, and interpreted in ways that are maximally responsive to the ultimate objectives (IOM, 2011a) and interactions between systematic review teams and the committee who will eventually use the systematic reviews to develop recommendations are considered critical. Such interactions may occur at the beginning and end of the systematic review process, at various stages during the process, or throughout—in cases where systematic reviews are conducted by members of the guideline review panel. Tradeoffs of different models for such interactions relate to (1) the ability to achieve maximum responsiveness of the systematic review to the guideline panel’s questions and needs (which favors more interaction); (2) avoiding undue influence of guideline panel members on the systematic review process (which favors less interaction); and (3) the extent to which the guideline panel can fully understand the systematic review results as they review and interpret them when judging the evidence and making recommendations (which favors at least a minimum level of well-timed interaction). For feasibility or efficiency, the systematic reviews conducted to support DRI committees may be conducted and completed before the DRI committees are appointed. These DRI reviews are conducted by systematic review teams with expertise specific to a nutrient or cluster of

related nutrient. As shown in Figure 1-2, a technical expert panel, which is appointed to assist with developing the systematic review protocol, literature search strategies, and approaches to specific issues, interacts with the systematic review team and also may be represented in the eventual DRI committee membership, providing for overlap. Members of the systematic review team itself also may be represented on the DRI committee as members or consultants. Also of note in Figure 1-2, the final decisions about implementation of DRIs are in the domain of risk management and are, therefore, made by the federal agencies rather than the DRI committees; they draw heavily on the content of the DRI report while also incorporating key policy or programmatic considerations in their deliberations and decisions. In other models, the same committees that use the systematic reviews to evaluate the evidence are also expected to make policy recommendations.

Population of Interest

The phrase “apparently healthy population” (or “general population” or “healthy population”) has been used by past DRI committees as a way to define the population covered by the DRIs. It excludes those individuals who (1) have a chronic disease that needs to be managed with medical foods, (2) are malnourished (undernourished), (3) have diseases that result in malabsorption or dialysis treatments, or (4) have increased or decreased energy needs because of disability or decreased mobility. The statement of task requests that this committee use “apparently healthy population” in a manner consistent with the Options Report.

The committee generally agrees that the guiding principles in this report apply to the “apparently healthy population.” However, because “apparently healthy population” potentially encompasses a diverse group of individuals with many different health conditions, the committee also highlights the need for DRI committees to characterize the health status of the population in terms of who is included and excluded for each DRI. Specifically, based on the committee’s interpretation of the statement of task, the committee recognizes (1) that an “apparently healthy population” includes a substantial proportion of individuals who have obesity and other chronic conditions, such as hypertension or diabetes, (2) that everyone in the population is theoretically at risk of developing such chronic conditions, and (3) that identification of intake levels or ranges related to chronic disease risks has not been the focus of the traditional DRI process. Therefore, this recommendation for a formal approach to adding chronic conditions to the DRI process begins with clarification that the “apparently healthy” population of interest includes people at risk of or with chronic conditions who do not meet the DRI exclusion criteria that exist at that time. Also, the committee recognizes that specific DRIs may be appropriate for certain

subgroups within the apparently healthy population in cases where relevant study design and approaches to risk stratification are considered sufficiently robust to warrant this. With this in mind, DRI committees will address these populations as appropriate.

NUTRIENTS AND OTHER FOOD SUBSTANCES

As the statement of task requests, the committee refers to food substances as “consist[ing] of nutrients that are essential or conditionally essential, energy nutrients, or other naturally occurring bioactive food components.” The term “nutrients or other food substances (NOFSs)” is used throughout the report.

NOFSs, however, are not consumed in one single form, but can be consumed in a variety of chemical forms and within matrixes, such as in a dietary supplement or in a fortified food. Reflecting this, the evidence base to evaluate the confidence in the causal relationship between an NOFS and a health outcome will derive from studies where the NOFS is ingested in a variety of chemical forms either as part of a food or as a dietary supplement that might influence health. The chemical form and the matrix might influence its interactions, availability, and bioequivalence. Therefore, consumption of an NOFS as part of a food cannot be assumed to result in equivalent effects as consumption of the same NOFS as a dietary supplement and a scientific evaluation will have to be made about whether the results are comparable.

Out of Scope

In following a risk model paradigm, the process of establishing DRIs includes risk assessment and risk management activities (see Figure 1-2). As mentioned above, the committee’s task is limited to providing recommendations and guiding principles in regard to the risk assessment activities within the first two steps of the risk assessment model—risk identification and risk characterization. The committee did not address activities related to formulating the problem or applying the DRIs, which are the purview of the U.S. and Canadian DRI steering committees. Although DRI committees will need to consider health-related risks and benefits and risk reduction goals for the population, other important factors, such as cost, judgments, and values, or implementation factors, are considered the purview of the U.S. and Canadian DRI steering committees and, therefore, also outside of the scope of work of this committee. Because a well-conducted systematic review is essential, this report includes guiding principles related to selected aspects of conducting scientifically rigorous systematic reviews, such as the systematic review protocol.

The committee recognizes that chronic disease DRIs for certain groups might need to be adjusted based on physiological and lifestyle characteristics. Based on the statement of task, which requests that the committee focus on Steps 1 and 2 of the risk assessment framework (see Annex), this report does not address such potential modifications. The committee also recognizes that, in individuals with certain diseases, risk of diseases, or nutrient deficiency diseases, the requirements for nutrients will be different from those for the “apparently healthy population.” This report does not address establishing such reference intake levels as those are typically addressed by reference to clinical guidelines for disease management. In addition, this report does not address changes in nutrient requirements in cases where a nutrient may augment the effect of a pharmaceutical. For regulatory purposes, in these cases, the nutrient is considered to be part of the drug (e.g., the possible beneficial effects of higher levels of folate when given in combination with certain pharmaceuticals).

Audience for This Report

The statement of task explains that the guiding principles will be used to include chronic disease endpoints for NOFSs by future National Academies committees as they establish DRIs. The process of establishing DRIs, however, implies the coordinated work of various groups of individuals (e.g., systematic review team, technical expert panel, risk managers, and DRI committees; see Figure 1-2). Therefore, for greatest value and effectiveness of the process, some of the recommendations and guiding principles might need to be considered by the systematic review team, the sponsors or others, as they develop the protocol and tasks for DRI committees.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The report is organized into three background chapters (Chapters 1, 2, and 3) and five chapters that directly address the statement of task (Chapters 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8). Chapter 2 describes general aspects of the current DRI process and describes more specifically how chronic diseases have been included in DRIs for some nutrients, and approaches taken by past committees to resolve challenges. Chapter 3 explains the conceptual and methodological challenges when exploring the association of NOFSs with chronic disease. The remainder of the report describes in more detail the conceptual and methodological challenges and justifications for the options selected as well as guiding principles for including chronic disease in the DRI process. In describing the challenges, the reader is frequently directed to the Options Report (see Appendix B) for more extensive explanations. Chapters 4 and 5 describe challenges and approaches regarding the ascertainment of dietary

intake and measurement of health outcomes, respectively. Chapters 6 and 7 aim to answer the two core questions of this report: (1) What are acceptable levels of confidence that the relationship between an NOFS and a chronic disease is causal?, and (2) If a causal relationship exists, what are acceptable levels of confidence in the data to establish an intake-response relationship and what are approaches for identifying and characterizing the intake-response relationship and, if appropriate, to recommend DRIs? (see Chapter 7). Issues related to the DRI organizational process itself are addressed in Chapter 8. Before deliberating the questions in the task, the committee agreed on a set of important definitions (see Appendix D).

Table 1-1 provides a roadmap of the report where the reader can find, by chapter, the questions addressed and the relevant options.

TABLE 1-1 Roadmap of the Report

| Chapter | Questions Addressed | Relevant Options (from Yetley et al., 2017) |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Introduction | Why do we need guiding principles? What is the objective of the guiding principles for establishing DRIs based on chronic disease? | N/A |

| What is the task and what subjects are outside of the task? | ||

| How is the report organized? | ||

| 2: Current Process to Establish Dietary Reference Intakes | What are the DRIs and the process to establish them? To whom do they apply? | N/A |

| What types of NOFSs and outcomes have DRIs addressed? | ||

| How are DRIs used in nutrition policy? |

| Chapter | Questions Addressed | Relevant Options (from Yetley et al., 2017) |

|---|---|---|

| 3: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges in Establishing Chronic Disease Dietary Reference Intakes | What types of conceptual and methodological challenges are associated with assessing NOFS intake and NOFS-chronic diseases research to inform DRIs based on chronic disease outcomes? | N/A |

| How might these challenges affect the certainty of judgments about evidence about causal or intake-response relationships between NOFSs and chronic diseases? | ||

| 4: Methodological Considerations Related to Assessing Intake of Nutrients of Other Food Substances | How should use of biomarkers of intake and self-report dietary intake methodologies influence ratings of study quality? | N/A |

| 5: Measuring Chronic Disease Outcomes | How should relevant outcomes be selected for inclusion in a systematic review and for inclusion in the review of the evidence? |

OPTIONS FOR JUDGING THE EVIDENCE

|

| What methodological issues should be considered when assessing the quality of outcome data? |

| Chapter | Questions Addressed | Relevant Options (from Yetley et al., 2017) |

|---|---|---|

| 6: Evidence Review: Judging the Evidence for Causal Relationships | What are established approaches for assessing causal factors in relation to chronic diseases generally, and how does one optimally apply these approaches to NOFS-chronic disease questions? |

OPTIONS FOR JUDGING THE EVIDENCE

|

| How do different study designs potentially contribute to judgments about causal relationships of NOFS intakes or exposures to chronic diseases? | ||

| 7: Intake-Response Relationships and Dietary Reference Intakes for Chronic Disease | What methods should be used to describe the relationship between NOFS intake and chronic disease? What tools, approaches, or instruments should be used to assess the certainty of the evidence in the data for an intake-response relationship between an NOFS and a chronic disease? |

OPTIONS FOR INTAKE-RESPONSE RELATIONSHIPS

|

| 8: The Process for Establishing Chronic Disease Dietary Reference Intakes | How should the new DRI process be integrated into the current process of establishing DRIs for adequacy and toxicity? |

OPTIONS FOR THE NEW DRI PROCESS

|

| Should the task be to establish DRIs related to individual NOFSs or to NOFSs that are related? |

REFERENCES

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2012. Second national report on biochemical indicators of diet and nutrition in the U.S. population 2012. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Environmental Health.

CDC. 2014. Deaths and mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm (accessed May 16, 2017).

CDC. 2017. Chronic disease overview. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview (accessed May 16, 2017).

Health Canada. 2012. Do Canadian adults meet their nutrient requirements through food intake alone? http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/alt_formats/pdf/surveill/nutrition/commun/art-nutr-adult-eng.pdf (accessed July 14, 2017).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 1988. The Surgeon General’s report on nutrition and health. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1994. Food components to enhance performance: An evaluation of potential performance-enhancing food components for operational rations. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. Dietary Reference Intakes: Guiding principles for nutrition labeling and fortification. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2006a. Mineral requirements for military personnel: Levels needed for cognitive and physical performance during garrison training. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2006b. Nutrient composition of rations for short-term, high-intensity combat operations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2010. Evaluation of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in chronic disease. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011a. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011b. Dietary Reference Intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011c. Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Murphy, S. P., A. A. Yates, S. A. Atkinson, S. I. Barr, and J. Dwyer. 2016. History of nutrition: The long road leading to the Dietary Reference Intakes for the United States and Canada. Adv Nutr 7(1):157-168.

NRC (National Research Council). 1989. Diet and health: Implications for reducing chronic disease risk. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Taylor, C. L. 2008. Framework for DRI development: Components “known” and components “to be explored.” Washington, DC.

USDA and HHS. 2015. Scientific report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/PDFs/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf (accessed May 16, 2017).

Ward, B. W., J. S. Schiller, and R. A. Goodman. 2014. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: A 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis 11:E62.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2014. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Yetley, E. A., A. J. MacFarlane, L. S. Greene-Finestone, C. Garza, J. D. Ard, S. A. Atkinson, D. M. Bier, A. L. Carriquiry, W. R. Harlan, D. Hattis, J. C. King, D. Krewski, D. L. O’Connor, R. L. Prentice, J. V. Rodricks, and G. A. Wells. 2017. Options for basing Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) on chronic disease endpoints: Report from a joint US-/ Canadian-sponsored working group. Am J Clin Nutr 105(1):249S-285S.

ANNEX 1-1

STEPS OF THE DRI ORGANIZING FRAMEWORK6

Step 1: Indicator Review and Selection

An initial starting point for this report—as for all deliberations based on risk assessment—is the identification and review of the potential indicators to be used. Based on this review, the indicators to be used in developing DRIs are selected. As described within the DRI framework, this step of indicator identification is outlined as follows.

- Literature reviews and interpretation. Subject-appropriate and well-done systematic evidence-based reviews as well as other relevant scientific reports and findings serve as a basis for deliberations and development of findings and recommendations for the nutrient under study. De novo literature reviews carried out as part of the study are well documented, including, but not limited to, information on search criteria, inclusion/exclusion criteria, study quality criteria, summary tables, and study relevance to the task at hand consistent with generally accepted methodology used in the systematic review process.

- Identification of indicators to assess adequacy and excess intake. Based on results from literature reviews and information gathering activities, the evidence is examined for potential indicators related to adequacy for requirements and the effects of excess intakes of the substance of interest. Chronic disease outcomes are taken into account. The approach includes a full consideration of all relevant indicators, identified for each age, gender, and life stage group for the nutrients under study as data allow.

- Selection of indicators to assess adequacy and excess intake. Consistent with the general approach, indicators are selected based on the strength and quality of the evidence and their demonstrated public health significance, taking into consideration sources of uncertainty in the evidence. They are in consideration of the state of the science and public health ramifications within the context of the current science. The strengths and weaknesses of the evidence for the identified indicators of adequacy and adverse effects are documented.

___________________

6 Note: Adapted from the DRI Organizing Framework as described in the 2011 Institute of Medicine report Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D (IOM, 2011b, pp. 27-29).

Step 2: Intake-Response Assessment and Specification of Reference Values

The intake-response relationships (commonly referred to as dose-response relationships) for the selected indicators of adequacy and excess are specified to the extent the available data allow. If the available information is insufficient, then appropriate statistical modeling techniques or other appropriate approaches that allow for the construction of intake-response curves from a variety of data sources are used. In some instances, most notably for the derivation of UL relative to excess intake, it is necessary to make use of specified levels or thresholds in the absence of the ability to describe a dose-response relationship, specifically a no observed effect level or a lowest observed effect level. Furthermore, the levels of intake determined for adequacy and excess are adjusted as required, appropriate, and feasible by uncertainty factors, variance in requirements, nutrient interactions, bioavailability and bioequivalence, and scaling or extrapolation.

Step 3: Intake Assessment

Consistent with risk assessment approaches, after the reference value is established, based on the information derived from scientific studies, an assessment of the current intake of the nutrient of interest is carried out in preparation for the discussion of implications and special concerns. That is, the known intake is examined in light of the reference value established. Where information is available, an assessment of biochemical and clinical measures of nutritional status for all age, gender, and life-stage groups can be a useful adjunct.

Step 4: Discussion of Implications and Special Concerns

Characterization of the implications and special concerns is a hallmark of the organizing framework. For DRI purposes, it includes an integrated discussion of the public health implications of the DRIs and how the reference values may need to be adjusted for special vulnerable groups within the normal population. As appropriate, discussions on the certainty/uncertainty associated with the reference values are included as well as ramifications of the committee’s work that the committee has identified as relevant to its risk assessment tasks.