3

Conceptual and Methodological Challenges in Establishing Chronic Disease Dietary Reference Intakes

Chapters 1 and 2 provide context for the committee’s task of providing recommendations and guiding principles for chronic disease Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs). This chapter further highlights several conceptual and methodological considerations that are specific to nutrition science issues or for which the committee felt that explicit guidance was needed for making judgments about causal or intake-response relationships related to nutrients or other food substances (NOFSs) and chronic diseases. As described in more detail in Chapter 6, the general process of judging evidence about causal relationships between exposures or interventions and health outcomes is well established. The use of carefully specified and conducted systematic reviews is at the core of this process.

Systematic reviews to guide health policy and practice require specification of questions of interest and systematic literature reviews, which identify and assess individual studies and summarize and rate the body of evidence for each question (Brannon et al., 2014). The questions themselves relate to judgments about causal attribution of certain benefits and harms to particular health-related exposures or interventions. The challenge in the nutrition field is how this process can best be applied for various food or nutrition policy purposes, and—in this case—specifically for developing NOFS-chronic disease DRIs. The relevant systematic review and evidence rating methods were developed initially to provide guidance for clinical and pharmacological therapeutics. Systematic reviews in nutrition have many special challenges not present in reviews of pharmacologic agents, even without adding the complexity of chronic disease endpoints.

As discussed in this chapter, NOFS-chronic disease questions raise spe-

cial considerations when applying these methods. The evidence base related to these questions is characterized by biological, behavioral, or study design factors that may lower the certainty of judgments associated with a given body of evidence. These factors include

- Characterizations of nutrient intake or exposures of individuals,

- Ways to account for intra- or inter-personal biological variations in effects of nutrient exposure,

- Nutrient interrelationships,

- Subpopulation differences in effects of a given nutrient intake,

- Study designs available for making causal judgments, and

- Intra- and inter-person variability in measures of exposure and outcome.

The nature of the challenges relates in part to the level at which diet or nutrition is being considered. Tapsell et al. (2016) conclude that establishing relationships between nutrients and health outcomes may present the greatest challenges, and should be guided by first establishing relationships for whole dietary patterns and then for specific foods. When DRIs for essential nutrients are the starting point, health effects of nutrients based on adequacy and toxicity are extremely difficult to isolate from the foods and dietary patterns through which nutrient exposures are created. Also, due to these challenges, careful interpretation of results from nutrition research is essential in order to understand the effects of NOFSs. For example, results from observational studies might appear inconsistent with results from large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) unless they are carefully evaluated (Bazzano et al., 2006; Chew et al., 2015; Ye et al., 2013).

This report can be seen as part of a broader effort to articulate the relevant challenges and to provide guidance for how to take nutrition-related evidence issues into account in evidence reviews to support public health nutrition (Brannon et al., 2014; Chung et al., 2009; Dwyer et al., 2016; Lichtenstein et al., 2008; Russell et al., 2009; Tapsell et al., 2016; Tovey, 2014). Many of these challenges were outlined in Options for Basing Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) on Chronic Disease Endpoints: Report from a Joint US-/Canadian-Sponsored Working Group (i.e., the Options Report) (Yetley et al., 2017) (see Appendix B). This report was the foundation for the committee’s statement of task (see Chapter 1, Box 1-1) and offered options that the committee was asked to consider in making its recommendations. The remainder of this chapter explains and illustrates the issues that contribute to the uncertainty of causal judgments about nutrient-chronic disease relationships. It is intended to serve as a reference point when reading Chapters 4 through 8. A case study of vitamin D, adapted from the evidence review for the 2011 update of the DRI for calcium and

vitamin D (IOM, 2011), is included at the end of this chapter to illustrate the general concepts and complexities that may apply, variably, to many nutrients and chronic diseases.

CHARACTERIZING NUTRIENT INTAKES (EXPOSURES)

Documenting what people eat to the greatest possible degree of certainty is fundamental for assessing NOFS-chronic disease relationships because the relationships themselves carry an inherent measure of uncertainty. Chronic diseases are multifactorial, and the role of any one factor will not be known precisely. Controlled feeding studies, which encompass recording of pre- and post-meal weights of known foods, offer fewer opportunities for measurement errors. Some short-duration feeding studies have used surrogate outcomes to estimate effects on chronic disease pathways (e.g., Sacks et al., 1995). However, because of their costs (e.g., they require more time for research staff to monitor and record intakes and conduct quality control procedures), they are mainly used to assess actual intakes of nutrients or foods over short periods of time, primarily in validation studies where reference intake estimates can be used to assess the accuracy of dietary intake reporting or to validate biomarkers. To examine risk associated with long-term exposure, information on nutrient exposures is usually obtained from some type of dietary assessment. These assessments, whether from foods or dietary supplements or botanicals, are always imperfect, in part because there is variation in what people eat from day to day, and also because people’s ability to recall or record what they eat involves error. Systematic biases in dietary reporting also may occur, by sex, age, and weight status, and they may affect the validity of the resulting values. Chapter 4 provides an overview of the various methods of food intake assessment, their strengths and limitations, and implications for the tasks of systematic review teams and DRI committees.

For DRI purposes, documenting the amount of a nutrient within foods is of central importance, beyond assessment of the intake of foods themselves. Additional error is introduced due to limitations in nutrient composition databases, which vary in quality for different nutrients. In addition, factors such as the chemical form of the nutrient or its bioavailability have not always been taken into account.

These potential sources of error in exposure assessment can have an impact on the ability to draw clear conclusions from a given study. In observational studies, random error may decrease the ability to see true associations, and unintentional bias in reporting by certain subgroups may affect the distribution of intake, further affecting validity. The impacts of these biases are not always predictable. In RCTs, an intervention to increase or decrease a nutrient assumes that baseline intake has been correctly

characterized and that subsequent reports of food intake will reflect the achieved differences in intake between intervention and control groups. The information on achieved differences between groups, however, is often not available in published RCTs. Furthermore, because relatively few interventions are designed to compare more than one intake level to the control, intake-response relationships are often based on strata of achieved intakes, as reported by trial participants (because respondents will vary in dietary adherence), which may break the random assignment to the treatment groups.

ACCOUNTING FOR BIOLOGICAL FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE NUTRIENT EXPOSURES

Nutrient intakes, even when assessed with minimal error, may not necessarily reflect the biological exposures that influence chronic disease pathways. As indicated above, the biological “dose” associated with a given amount of food is affected by the chemical form of the nutrient and its digestibility and bioavailability in the human gastrointestinal tract. This may or may not be accounted for in nutrient database tables. In addition, digestibility, and therefore availability of certain nutrients, may be affected by other components of a meal. Different chemical forms of nutrients may vary in biological activity, requiring conversion to equivalent units for evaluation of intake. An individual’s baseline nutrient status is another potential influence, which may affect absorption and utilization of the dietary source. Some of these issues will affect the interpretation of blood levels or tissue levels that might be used as biomarkers of intake as an alternative to or in conjunction with dietary intake data (see Chapter 4). These biological factors may be most important for DRI considerations when they are known or thought to vary systematically in subpopulations. In this case, such variation can be considered when formulating questions to guide systematic reviews.

ISOLATING EFFECTS OF SINGLE NOFS OR NOFS-CHRONIC DISEASE PATHWAYS

Isolating single NOFS effects is challenging if not theoretically impossible. Many NOFS functions are interrelated and may affect more than one biological pathway, and any one biological pathway may be affected by multiple NOFSs. In addition, there is collinearity in NOFS intake. Thus, both confounding by and interactions among NOFSs must be considered. Mapping these potential relationships in logic models or analytic frameworks helps to identify these considerations when framing questions to guide systematic reviews. Mapping the evidence identified can also be help-

ful for understanding relationships and patterns. For example, in Table 3-1, which is based on a World Health Organization dietary guidance report (WHO/FAO, 2003), several rows indicate associations of nutrients or nutrient sources with more than one of the six disease outcomes, and several of the columns for disease outcomes indicate associations with more than one NOFS variable. The source table for the excerpts in Table 3-1 also included variables based on food or beverage groups that may be of interest because of their nutrient or bioactive food substance (e.g., polyphenol) content with potential chronic disease risk reduction benefits. However, such variables had not been analyzed in terms of these specifics nutrients or food substances.

In individuals who do not use nutrient supplements, the range of intakes may be narrow within a given population with day-to-day variation that makes it difficult to identify group differences. Among those who do use supplements, single nutrient supplements will be associated with a substantially higher range of doses than would be obtained from food sources, facilitating clear comparisons if supplement intake is ascertained. The same would apply to supplements of botanicals (e.g., cucurmin from turmeric). A complication that sometimes remains is that the form of the NOFS in a supplement may be qualitatively different from the form that is in food, with different pathways or potency of effect. Use of multivitamin supplements limits ability to attribute any effect of the supplement to a specific nutrient.

Intervention trials involving supplements can evaluate effects of the supplement dose as an increase over baseline intake in the study population. However, for a variety of behavioral and biological reasons, answers to DRI questions may require studies that vary NOFS intakes based on dietary advice. In this case, the intervention unavoidably involves changes in intake of other NOFSs present in the foods for which consumption is changed, and these NOFSs will vary according to participant food choices as well as the degree of compliance. Changes in targeted and non-targeted NOFSs in comparison groups can be evaluated through dietary reports or biomarkers of intake (where available) to help with the attribution of any observed changes in outcome to the intervention assignment.

ASSESSING BIASES DUE TO STUDY DESIGNS

Basing judgments about causal relationships using the typical biomedical hierarchy of study designs inherently lessens the ability to make definitive judgments about NOFS-chronic disease questions because the relevant evidence is much more likely to rely on observational study designs, rather than RCTs. RCTs are at the top of the hierarchy (i.e., are the strongest study designs) when it comes to internal validity for judging causality (Yetley et

TABLE 3-1 Summary of the Strength of Evidence for Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), Cancer, Dental Disease, and Osteoporosisa

| Obesity | Type 2 Diabetes | CVD | Cancer | Dental Disease | Osteoporosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy and fats | ||||||

| High intake of energy dense foods | C↑ | |||||

| Saturated fatty acids | P↑ | C↑b | ||||

| Trans fatty acids | C↑ | |||||

| Dietary cholesterol | P↑ | |||||

| Myristic and palmitic acid | C↑ | |||||

| Linoleic acid | C↓ | |||||

| Fish and fish oils (EPA and DHA) | C↓ | |||||

| Plant sterols and stanols | P↓ | |||||

| α-Linolenic acid | P↓ | |||||

| Oleic acid | P↓ | |||||

| Stearic acid | P-NR | |||||

| Nuts (unsalted) | P↓ | |||||

| Carbohydrate | ||||||

| High intake of NSP (dietary fiber) | C | P↓ | P↓ | |||

| Free sugars (frequency and amount) | C↑c | |||||

| Sugar-free chewing gum | P↓c | |||||

| Starchd | C-NR | |||||

| Wholegrain cereals | P↓ | |||||

| Vitamins | ||||||

| Vitamin C deficiency | C↑e | |||||

| Vitamin D | C↓ f | C↓g | ||||

| Vitamin E supplements | C-NR | |||||

| Folate | P↓ | |||||

| Minerals | ||||||

| High sodium intake | C↑ | |||||

| Salt-preserved foods and salt | P↑h | |||||

| Potassium | C↓ | |||||

| Calcium | C↓g | |||||

| Fluoride, local | C↓c | |||||

| Fluoride, systemic | C↓c | P-NRg | ||||

| Fluoride, excess | C↑f | |||||

| Hypocalcaemia | P↑f | |||||

NOTES: C↑ = convincing increasing risk; C↓ = convincing decreasing risk; C-NR = convincing, no relationship; DHA = docosahexaenoic acid; EPA = eicosapentaenoic acid; P↑ = probable increasing risk; P↓ = probable decreasing risk; P-NR = probable, no relationship.

a Only convincing (C) and probable (P) evidence are included in this summary table.

b Evidence also summarized for selected specific fatty acids; see myristic and palmitic acid.

c For dental caries.

d Includes cooked and raw starch foods, such as rice, potatoes and bread. Excludes cakes, biscuits, and snacks with added sugar.

e For periodontal disease.

f For enamel developmental defects.

g In populations with high fracture incidence only; applies to men and women more than 50-60 years old.

h For stomach cancer.

SOURCE: Adapted from WHO/FAO (World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization). 2003. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: Report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

al., 2017). Assigning study participants to treatment or control groups at random balances extraneous factors across treatment groups and permits attribution of differences in study outcomes to the NOFS intervention being tested. Participants in observational studies are assigned to comparison groups based on the estimated exposure to the NOFS of interest, which may be related to other personal characteristics or behaviors. Furthermore, these characteristics or behaviors may also affect study outcomes, which limits the certainty that an apparent causal relationship is due to the NOFS, as opposed to other factors. Residual confounding due to lack of proper statistical adjustments, untestable assumptions, or measurement error limits the causal certainty, even with the best observational study design and execution. However, RCT designs have limitations for answering NOFS-chronic disease questions, and observational data are indispensable for certain aspects of the process of developing DRIs, including chronic disease DRIs.

The availability of NOFS-chronic disease RCTs is limited primarily by cost and feasibility issues associated with conducting very large trials of long duration needed to allow time for disease to become apparent, and in enough people to observe a causal effect if one is present. For example, the dietary modification trial within the U.S. Women’s Health Initiative study was designed to follow 48,000 women, to be enrolled at 40 research sites around the United States and followed for an average of 8 years to understand the role of reduction of dietary total fat intake in preventing breast cancer (Prentice et al., 2006). The trial involved only women ages 50 years and older, which increased the likelihood of observing sufficient study endpoints to indicate a disease outcome. Smaller and shorter trials can be conducted if biomarkers of chronic disease risk are acceptable, rather than actual disease outcomes. However, certainty of conclusions from such trials will be limited to the extent that the marker is not completely equivalent to the disease. This issue is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5. Finally, RCTs are limited in their ability to test varying doses or combinations of an intervention, because adding treatment conditions can require a marked increase in trial size.

Other limitations of NOFS-chronic disease RCTs may include incomplete compliance with treatment, which is common in trials that rely on dietary behavior change counseling to achieve the intervention effect. Trials also have the potential for non-targeted changes in dietary behavior among participants, which could confound interpretation of the intervention effect. For example, counseling to reduce total fat intake might incidentally lead to reduction in caloric intake and weight change, which could also affect chronic disease development apart from the fat composition of foods consumed. However, such factors can be partially accounted for with a proper statistical analysis. NOFS interventions that use supplements to increase NOFS intake are easier to implement and sustain than those based on

extensive counseling, although control group participants may obtain and take the supplement on their own. Importantly, translation of the effect of the supplement may differ for that from dietary sources, complicating translation to dietary recommendations (as opposed to supplement use recommendations).

In contrast to RCTs, longitudinal cohort studies in which intake of the NOFS is assessed at the time of enrollment and, in many cases, periodically thereafter, lend themselves to long-term follow-up for disease development under natural living conditions. Observational studies are the only source of information about extant eating patterns in populations of interest for DRI development and are, therefore, a reference point for understanding intake-response relationships and interpretation of DRIs by users. They are usually much less costly than large RCTs, especially the multiple RCTs or intervention arms that would be needed to observe effects of varying levels of intake of the NOFS of interest. However, the potential confounding effects of other factors, if not accounted for (e.g., age or other characteristics of the individual, other nutrients in the diet, exposure to other chronic disease factors), can lead to erroneous conclusions, and determining the certainty of conclusions about causal relationships must be carefully considered in each study. The inherent susceptibility of dietary assessments to systematic error also affects the certainty of evidence from observational studies; unlike trials, in which the intervention is the basis for the comparison, the classification on usual dietary intake is the basis for the comparison in observational studies (see Chapter 4). In observational studies, the range of exposure reflects the prevailing intakes. Hence, when optimal intake is outside of the usual range, other studies will be needed. Recognizing that causal relationships are mainly inferred from RCTs, observational studies are still critical to inform conclusions about likely causal relationships, and to support evidence on intake-response relationships.

Chapter 6 reviews considerations for incorporating evidence from observational studies when making causal judgments. In this respect, differences among types of observational studies should be recognized. Prospective studies in which NOFS intake is ascertained before disease develops are stronger designs for inferring causality than are those that obtain dietary and disease data at the same time (e.g., cross-sectional studies or retrospective case-control studies). In the latter, reverse causality—an effect of the disease on the diet—and recall bias—an effect of knowledge of the disease on the accuracy of the self-report—are major threats to study validity, making it unlikely that such studies would be judged other than as low certainty. This issue does not apply to historical or “nested” case-control studies in which pre-existing data on dietary intake or a biomarker of intake are available.

VITAMIN D CASE STUDY

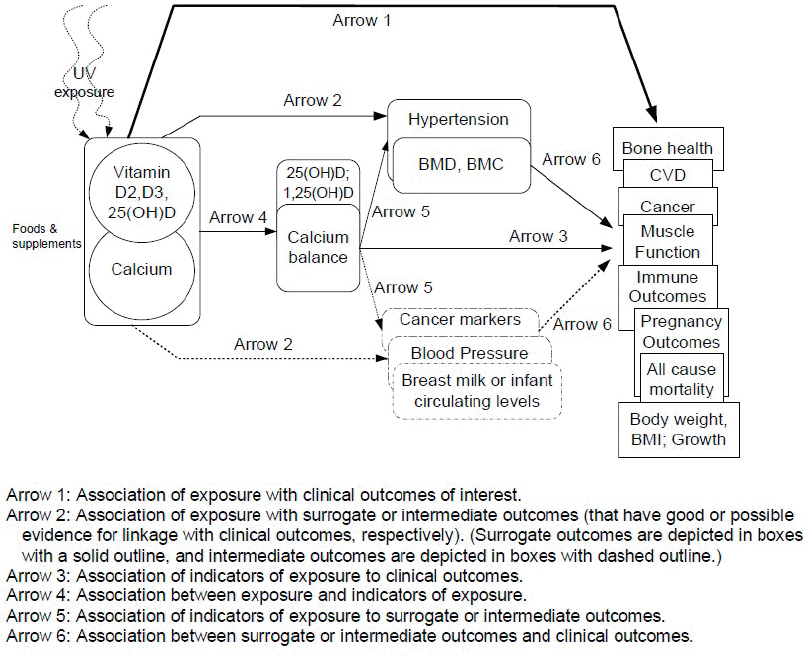

This section uses a case study on the recent process to update vitamin D and calcium DRIs to briefly illustrate some of the nutrition-specific issues discussed above. The overall process for the calcium and vitamin D DRI update was described generally in Chapter 1 of this report (see Figure 1-2 and associated narrative). The reader is also referred to the methods described in detail in Appendix D of the calcium and vitamin D DRI report (IOM, 2011), from which this case study was developed and which includes an explanation of the roles of the various entities involved (e.g., the federal sponsors, technical expert panel, and the Evidence-based Practice Centers [EPCs]) and the conduct of the systematic reviews. The process for gathering and summarizing evidence was based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (AHRQ, 2014; IOM, 2011). Figure 3-1

NOTES: BMC = bone mineral content; BMD = bone mineral density; BMI = body mass index; CVD = cardiovascular disease.

SOURCE: IOM, 2011.

shows the analytic framework used to identify beneficial effects, developed by the sponsoring agencies, in consultation with the technical expert panel and EPC methodologists. It shows the multiple sources of vitamin D, including sunlight as a non-dietary source, the inseparability of pathways involving vitamin D from those of calcium and the several clinical outcomes or surrogates to be considered when evaluating benefits of a given level of vitamin D intake. A similar figure, developed to identify pathways for potential adverse effects, included several additional outcomes.

The analytic framework guided the development and refinement of key questions (see Box 3-1) used to conduct the systematic review provided to the calcium and vitamin D DRI update committee. For the pathways related to bone health, the systematic review drew on a previously conducted systematic review of evidence on the effectiveness and safety of vitamin D in relation to bone health (Cranney et al., 2007; IOM, 2011).

Using vitamin D as a case example, Table 3-2 lists and explains nutrition-specific issues to be considered in establishing an NOFS-chronic disease DRI. The general challenges in evaluating NOFS-chronic disease relationships for DRI purposes are in the first column, with comments in

TABLE 3-2 Challenges in Evaluating NOFS-Chronic Disease Relationships to Inform DRIs, Illustrated Through the Case of Vitamin D

| 1. | Characterizing nutrient exposures in comparison groups | |

|

1.1. Assessment of nutrient intake from foods |

Assessment of intake of any nutrient by self-reports is subject to both random and systematic error; assessment must include vitamin D naturally occurring in foods and in fortified foods; fortified foods may contain different levels of vitamin D. | |

|

1.2. Assessment of intake from supplements |

Vitamin D in supplements may be as D2 or D3, which may vary in potency, and in various doses. Intakes from supplements may be more reliably ascertained by self-report, at least for regular users who can identify the specific product and dose. However, exposure to vitamin D from multivitamin preparations will be potentially confounded by other nutrients with effects on the same outcomes. | |

|

1.3. Assessing exposure from non-dietary sources |

The amount of vitamin D obtained from synthesis in the skin depends on sunlight exposure, for which estimation has a high degree of uncertainty. | |

|

1.4. Assessment of biomarkers of exposure |

Serum 25(OH)D concentrations are considered the best measure of total vitamin D exposure, but estimates of levels in serum vary within and across assay type and laboratory. | |

|

1.5. Assessing intake-response relationships |

Use of serum 25(OH)D concentrations reduces the uncertainty that would be associated with using self-reported intake data, but DRIs based on serum levels require translation of serum levels into recommendations for dietary intake from food and/or supplements, and consideration of the possibility that the vitamin D in supplements has different levels of biological activity compared to food sources. | |

| 2. | Accounting for biological factors that influence nutrient exposures | |

|

2.1. Nutrient bioavailability |

Bioavailability and metabolism of vitamin D may differ depending on source, various metabolic factors or other foods present at the time of digestion. | |

|

2.2. Bioequivalence or safety profiles of different chemical forms of a nutrient |

The forms of vitamin D (D2 or D3) considered as nutritional supplements may not have the same potency at a given dose. | |

|

2.3. Biological stores |

Vitamin D stored in body fat tissue is an endogenous source and may influence total exposure differentially, according to need. In addition, the amount of body fat influences the amount of vitamin D that is stored and its release into the circulation. Thus, overall vitamin D metabolism may differ in people with obesity. | |

|

2.4. Endogenous sources |

Sunlight (UV radiation) affects the amount of vitamin D synthesized in the skin. Exposure to sunlight is, therefore, of interest in studies of associations of vitamin D with health outcomes. | |

|

2.5. Interpretation of biomarkers |

Serum 25(OH)D concentrations may be useful as an indicator of exposure. This biomarker reflects effects of intake from foods, supplements, and sun exposure as well as metabolism of vitamin D in the liver and kidneys (activation) that affects vitamin D status. | |

| 3. | Nutrient interrelationships | |

|

3.1. Multiple potential clinical outcomes and surrogates |

Evidence review questions related to health effects of vitamin D address effects of vitamin D intake or serum 25(OH)D concentrations on growth, cardiovascular diseases, body weight outcomes, cancer, immune function, pregnancy or birth outcomes, mortality, fracture, renal outcomes, soft tissue calcification or on surrogate markers such as hypertension, blood pressure, and bone mineral density, and hypercalcemia; potential adverse effects of sunlight (as a “source” of vitamin D) are examined because of the potential for sunlight exposure to increase the risk of risk of non-melanoma or melanoma skin cancers. | |

|

3.2. Interrelated biological functions of nutrients |

The biological effects of vitamin D include influences of calcium and phosphorous nutriture. Key questions for the calcium/vitamin D systematic reviews attempted to address this issue by evaluating effects of calcium alone, vitamin D alone, and calcium combined with vitamin D. | |

|

3.3. Interpreting nutrient effects of food-based interventions |

Dietary interventions based on foods will reflect naturally occurring vitamin D as well as fortification with vitamin D and also will potentially be confounded by effects on the same outcomes by other nutrients or food substances in the same foods. For example, depending on the source, foods high in vitamin D may also contain significant amounts of omega-3 fatty acids, B vitamins, and potassium. | |

|

3.4. Interpreting nutrient effects based on supplement-based interventions |

Randomized controlled trials that provide vitamin D as a supplement potentially allow robust comparisons between intervention and comparison groups. Direct interpretation of such trials with respect to DRIs assumes bioequivalency of food and supplement forms. | |

|

3.5. Potential for non-linear intake-response |

As with any nutrient, a linear dose-response across the entire range of possible intakes cannot be assumed. For example, toxic effects are anticipated above the established upper limit for recommended vitamin D intake. | |

| 4. | Subpopulation differences in effects of a given level of intake | |

|

4.1. Children |

Bone-related outcomes include rickets, bone mineral density, bone mineral content, fractures, or parathyroid hormone. | |

|

4.2. Women of reproductive age, including those who are pregnant or lactating |

Bone-related outcomes include bone mineral density, heel bone fractures, or parathyroid hormone. | |

|

4.3. Elderly men and postmenopausal women |

Bone-related outcomes are bone mineral density, fractures, and falls. | |

|

4.4. Other subpopulations |

Effects of supplemental doses of vitamin D on bone outcomes may vary by ethnicity (e.g., due to differences in skin pigmentation and behaviors related to sunlight exposure), body mass index (e.g., due to effects on vitamin D storage and release from stores and possibly to behaviors related to sunlight exposure), or geography (e.g., due to variations in sunlight exposure at different latitudes). | |

| 5. | Study designs | |

|

5.1. Criteria for inclusion in systematic review |

Primary studies eligible for inclusion in the systematic review were “randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized, prospective comparative studies of interventions; prospective, longitudinal, observational studies (where the measure of exposure occurred before the outcome) and prospective nested case-control studies (case-control study nested in a cohort).” | |

| Observational studies with cross-sectional and retrospective case-control designs were excluded (IOM, 2011). | ||

the second column about how that challenge potentially affects evidence reviews and judgments related to benefits or risk of vitamin D exposure.

This chapter concludes the committee’s presentation of background and context, which is intended to provide a foundation for a consideration of the conceptual and methodologic issues involved in establishing chronic disease DRIs and the committee’s recommendations. The following two chapters take the next step by describing challenges and approaches involved in ascertaining dietary intake and measuring health outcomes. These activities provide the essential data needed to determine whether a causal relationship exists between an NOFS of interest and a chronic disease (Chapter 6) and whether a quantitative relationship between the NOFS and the chronic disease can be described with confidence (Chapter 7). The final chapter of the report addresses questions considered by the committee about the nature of the process to be used when developing chronic disease DRIs in relation to the existing DRI process, as described in Chapter 2.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2014. Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 10(14)-EHC063-EF. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

Bazzano, L. A., K. Reynolds, K. N. Holder, and J. He. 2006. Effect of folic acid supplementation on risk of cardiovascular diseases: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 296(22):2720-2726.

Brannon, P. M., C. L. Taylor, and P. M. Coates. 2014. Use and applications of systematic reviews in public health nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr 34:401-419.

Chew, E. Y., T. E. Clemons, E. Agron, L. J. Launer, F. Grodstein, P. S. Bernstein, and Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. 2015. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids, lutein/zeaxanthin, or other nutrient supplementation on cognitive function: The AREDS2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314(8):791-801.

Chung, M., E. M. Balk, S. Ip, G. Raman, W. W. Yu, T. A. Trikalinos, A. H. Lichtenstein, E. A. Yetley, and J. Lau. 2009. Reporting of systematic reviews of micronutrients and health: A critical appraisal. Am J Clin Nutr 89(4):1099-1113.

Cranney A., T. Horsley, S. O’Donnell, H. A. Weiler, L. Puil, D. S. Ooi, S. A. Atkinson, L. M. Ward, D. Moher, D. A. Hanley, M. Fang, F. Yazdi, C. Garritty, M. Sampson, N. Barrowman, A. Tsertsvadze, and V. Mamaladze. 2007. Effectiveness and safety of vitamin D in relation to bone health. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 158. (Prepared by the University of Ottawa Evidence-based Practice Center (UO-EPC) under Contract No. 290-02-0021.) AHRQ Publication No. 07-E013. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Dwyer, J. T., K. H. Rubin, K. L. Fritsche, T. L. Psota, D. J. Liska, W. S. Harris, S. J. Montain, and B. J. Lyle. 2016. Creating the future of evidence-based nutrition recommendations: Case studies from lipid research. Adv Nutr 7(4):747-755.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Dietary Reference Intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Lichtenstein, A. H., E. A. Yetley, and J. Lau. 2008. Application of systematic review methodology to the field of nutrition. J Nutr 138(12):2297-2306.

Prentice, R. L., B. Caan, R. T. Chlebowski, R. Patterson, L. H. Kuller, J. K. Ockene, K. L. Margolis, M. C. Limacher, J. E. Manson, L. M. Parker, E. Paskett, L. Phillips, J. Robbins, J. E. Rossouw, G. E. Sarto, J. M. Shikany, M. L. Stefanick, C. A. Thomson, L. Van Horn, M. Z. Vitolins, J. Wactawski-Wende, R. B. Wallace, S. Wassertheil-Smoller, E. Whitlock, K. Yano, L. Adams-Campbell, G. L. Anderson, A. R. Assaf, S. A. Beresford, H. R. Black, R. L. Brunner, R. G. Brzyski, L. Ford, M. Gass, J. Hays, D. Heber, G. Heiss, S. L. Hendrix, J. Hsia, F. A. Hubbell, R. D. Jackson, K. C. Johnson, J. M. Kotchen, A. Z. LaCroix, D. S. Lane, R. D. Langer, N. L. Lasser, and M. M. Henderson. 2006. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of invasive breast cancer: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA 295(6):629-642.

Russell, R., M. Chung, E. M. Balk, S. Atkinson, E. L. Giovannucci, S. Ip, A. H. Lichtenstein, S. T. Mayne, G. Raman, A. C. Ross, T. A. Trikalinos, K. P. West, Jr., and J. Lau. 2009. Opportunities and challenges in conducting systematic reviews to support the development of nutrient reference values: Vitamin A as an example. Am J Clin Nutr 89(3):728-733.

Sacks, F. M., E. Obarzanek, M. M. Windhauser, L. P. Svetkey, W. M. Vollmer, M. McCullough, N. Karanja, P.-H. Lin, P. Steele, M. A. Proschan, M. A. Evans, L. J. Appel, G. A. Bray, T. M. Vogt, T. J. Moore, and DASH Investigators. 1995. Rationale and design of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension trial (DASH). Annals of Epidemiology 5(2):108-118.

Tapsell, L. C., E. P. Neale, A. Satija, and F. B. Hu. 2016. Foods, nutrients, and dietary patterns: Interconnections and implications for dietary guidelines. Adv Nutr 7(3):445-454.

Tovey, D. 2014. The role of The Cochrane Collaboration in support of the WHO Nutrition Guidelines. Adv Nutr 5(1):35-39.

WHO/FAO (World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization). 2003. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: Report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Ye, Y., J. Li, and Z. Yuan. 2013. Effect of antioxidant vitamin supplementation on cardiovascular outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLOS ONE 8(2):e56803.

Yetley, E. A., A. J. MacFarlane, L. S. Greene-Finestone, C. Garza, J. D. Ard, S. A. Atkinson, D. M. Bier, A. L. Carriquiry, W. R. Harlan, D. Hattis, J. C. King, D. Krewski, D. L. O’Connor, R. L. Prentice, J. V. Rodricks, and G. A. Wells. 2017. Options for basing Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) on chronic disease endpoints: Report from a joint US-/ Canadian-sponsored working group. Am J Clin Nutr 105(1):249S-285S.