3

Overview of Agencies and Stakeholders

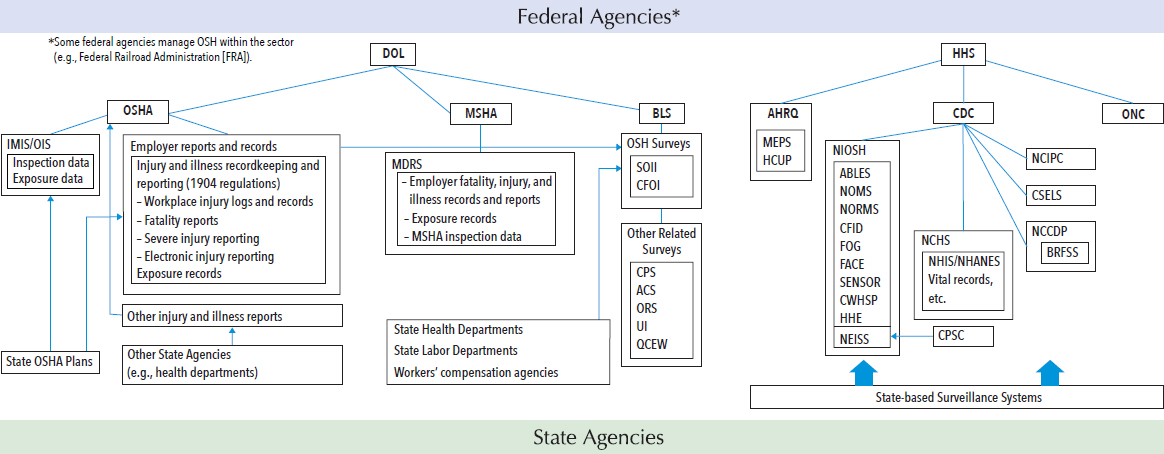

Occupational safety and health (OSH) surveillance is a collaborative effort of federal, state, and local agencies and stakeholders across employers, employee organizations, professional associations, and other organizations. The federal agencies that play the major roles in OSH surveillance are the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) in the Department of Labor, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). In addition, there are a number of other federal agencies with responsibilities and programs pertaining to OSH surveillance and prevention. State agencies also play a critical and complementary role in partnership with federal agencies. State agencies collect, analyze, and disseminate data from local sources to guide preventive action at the state, regional, and local levels; provide data to federal agencies to be aggregated for national surveillance; and fill in gaps in national surveillance data. The strong role of workers and employers is key to ensuring accurate and complete data and to using this information to implement improvements in worker safety and health at the workplace. In addition, health care facilities and organizations, workers’ compensation systems, and insurance companies have data that are relevant to occupational safety and health.

This chapter’s overview highlights the varying roles that different agencies and other stakeholders fill and provides background for discussions throughout the report on integrating and coordinating the multiple

surveillance databases and activities that span numerous sources.1 Additionally, the chapter provides a summary of the key recommendations made in the 1987 National Research Council (NRC) report, Counting Injuries and Illnesses in the Workplace: Proposals for a Better System, and points to an overview of progress to date on those recommendations (Appendix D).

BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

BLS in the Department of Labor has responsibilities for extensive data collection and analyses including statistical assessments of employment, unemployment, pay and benefits, inflation and prices, productivity, workplace injuries and illnesses, and consumer expenditures across the U.S. economy. Established in 1884 as an agency of the Department of the Interior, BLS has a long history of collecting statistical data on work-related injuries, illnesses, and fatalities, dating back to the late 1890s predating the Department of Labor. Early BLS reports in this area focused primarily on studies of individual industries, such as a 1909 report on phosphorous poisoning in the match-making industry (Drudi, 2015).

The inadequacies in workplace health and safety statistics and the need for an accurate uniform data reporting system for work-related injuries and illnesses were well recognized in the development of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-596; OSH Act). There was a general consensus that pertinent and reliable information was a prerequisite for effective health and safety programs. Section 24 of the OSH Act directed the Secretary of Labor, in consultation with the Secretary of Health and Human Services, to “develop and maintain an effective program of collection, compilation and analysis of OSH statistics.” These statistics were to include “all disabling, serious, or significant injuries and illnesses, whether or not involving loss of time from work, other than minor injuries requiring only first aid treatment and which do not involve medical treatment, loss of consciousness, restriction of work or motion, or transfer to another job.”

The Secretary of Labor delegated responsibility for this activity to BLS. Beginning in 1971, BLS implemented an annual nationwide survey (the Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses [SOII]) of a sample of private-sector employers to collect data on occupational injuries and illnesses (NRC, 1987). MSHA and the Federal Railroad Administration provide data on mining and railroad employees. As part of a Supplementary Data System, BLS also collected data on injuries, illnesses, and demographics

___________________

1 The committee’s review and report focused on OSH surveillance programs that pertain to the civilian workforce. The Department of Defense and military branches also have surveillance programs for military personnel, but those were not addressed in this report. A review and examination of the military’s surveillance programs could be considered in the future.

from 27 state workers’ compensation systems. The 1987 NRC review of these systems recommended modification of the Supplementary Data System given concerns about the accuracy and generalizability to the nation and the collection of more detailed data in the SOII (NRC, 1987). BLS subsequently discontinued the Supplementary Data System. In 1992, BLS implemented changes in the SOII by collecting more detailed information on injury and illness cases resulting in one or more days away from work. Two studies, one in New Jersey and one in Texas, performed at the request of the 1987 NRC committee, found that the BLS annual survey missed 50 percent of the acute traumatic work-related fatalities reported by employers. To address the undercount in fatalities, BLS in 1992 also implemented the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI). Both of these nationwide surveillance systems are population-based systems administered by BLS, working in collaboration with state agencies, most often state labor departments, that share the costs. CFOI and SOII are further described in Chapter 4.

BLS has a number of additional OSH surveillance initiatives that include, among others, examining the extent and factors contributing to undercounting in the SOII, exploring the feasibility of a nationwide household survey on nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses, and developing electronic tools for assigning standardized codes to narrative text information in occupational health and safety data sources (see further details in Chapters 4 and 6). BLS also conducts important research on OSH topics, such as an examination of workplace violence against psychiatric aids and technicians (BLS, 2015) and workplace injuries from falls (BLS, 2016a). BLS assists external researchers, providing access to SOII and CFOI microdata under strict conditions of confidentiality, as discussed below.

It has been BLS’s longstanding policy and practice to pledge to respondents that it will treat the microdata it receives through all of its surveys and other data collection efforts as confidential, including the SOII and CFOI, and use the data only for statistical purposes. Most of the surveys BLS conducts are voluntary and the agency relies on employers and others to participate and provide accurate and complete data, and believes that keeping their information confidential is vital to maintaining respondents’ trust and cooperation.

Since 2002, BLS has also been subject to the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (CIPSEA), federal legislation establishing uniform federal policy for the treatment of statistical data collected by federal statistical agencies under a pledge of confidentiality (PL 107-347). Under CIPSEA and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) implementing guidelines (OMB, 2007), statistical agencies are required to protect data collected under a pledge of confidentiality for solely statistical purposes and ensure that data are kept confidential and not used for any nonstatistical purposes without the informed consent of the respondent.

Nonstatistical purposes include any use of the data for regulatory or enforcement purposes. BLS is permitted under CIPSEA to provide access for its “agents,” including external researchers, to access confidential data; however, BLS must ensure that the data remain confidential and are only used for statistical purposes.

BLS has designated the data collected under both the SOII and CFOI as confidential and provided a pledge to respondents that all data will be used only for statistical purposes, maintained as confidential, and will not be released in identifiable form without informed consent2 (BLS, 2017).

Unlike other BLS surveys, the SOII is mandatory and the data on which the survey is based come directly from injury and illness records that are mandated by OSHA regulations. The workplace records on which the survey is based are not considered or treated as confidential by OSHA and are available to employers, employees, former employees, unions, OSHA and other government agencies. However, when these data are collected by BLS under CIPSEA, they are confidential and BLS can permit OSHA, other agencies, and researchers to use data only for statistical purposes and enforces this through a confidentiality agreement. Therefore, OSHA is not able to use the BLS collected data for regulatory or enforcement purposes and, as discussed below and in Chapter 6, has established a separate parallel collection system to seek similar establishment-level injury and illness data from employers.

OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

OSHA was created by the OSH Act of 1970. Under the Act, OSHA is responsible to “assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women by setting and enforcing standards and by providing training, outreach, education and assistance” (OSHA, 2017a). The Act also gave states the option to set up their own regulatory enforcement programs, subject to federal OSHA approval and oversight, and currently 26 states have OSHA-approved state plans in place (OSHA, 2017b). As specified in the OSH Act, OSHA covers most private-sector employers and their employees. State and local public-sector workers are covered only if a state has an approved state OSHA program. Federal employees are covered by

___________________

2 According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the CIPSEA confidentiality pledge for the SOII is as follows: “The Bureau of Labor Statistics, its employees, agents, and partner statistical agencies, will use the information you provide for statistical purposes only and will hold the information in confidence to the full extent permitted by law. In accordance with the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act of 2002 (Title 5 of Public Law 107-347) and other applicable Federal laws, your responses will not be disclosed in identifiable form without your informed consent” (BLS, 2017).

federal OSHA under Executive Order 12196. Self-employed individuals are among those excluded from the Act.3

Data sources compiled by OSHA include those that result from worksite inspections and data submitted by employers. These data assist in evaluating the safety of a workplace, understanding industry hazards, and identifying and implementing worker protections to reduce and eliminate hazards and prevent future work-related injuries and illnesses. All employers are required to notify OSHA within 8 hours of when an employee is killed on the job or within 24 hours when an employee has an in-patient hospitalization, amputation, or loss of an eye (OSHA, 2017c).

Workplace recordkeeping requirements are in place for work-related injuries and illnesses that require more than first aid in many worksites with more than 10 employees. Covered employers are required to keep a log of all work-related injuries and illnesses (OSHA Form 300), to keep more detailed reports on individual cases (OSHA Form 301), and to prepare an annual summary of injuries and illnesses (OSHA Form 300A), which must be posted from February through April of the following year at the worksite (see Appendix E). Employers are required to maintain these records for 5 years.4 The annual summary, OSHA 300 Log, and partial information from the OSHA 301 case reports must be made available to employees, former employees, and their representatives at the worksite if requested. OSHA and NIOSH have the right to access all of the injury and illness records that are required to be maintained.

The OSHA 300 Log and detailed OSHA 301 case reports are utilized by many employers, employees, and employee representatives for surveillance of injuries, illnesses, and hazards at the worksite. These reports also form the basis for the SOII. Employers in industries with a lower risk of serious injuries are exempt from these OSHA recordkeeping requirements, but may be required to participate in the BLS survey.5

___________________

3 The OSH Act provides that employees excluded from OSHA’s regulatory and enforcement coverage may be included in data collection and statistical programs.

4 In December 2016, OSHA issued a regulation clarifying that employers had an obligation to ensure the accuracy and completeness of injury records during the 5-year record retention period and that this requirement was enforceable by OSHA (2016a). In March 2017, Congress overturned this regulation under the Congressional Review Act, thereby limiting OSHA’s authority to enforce the obligation to keep complete and accurate records for a 6-month period after the occurrence of the injury. This action significantly limits OSHA’s ability to enforce injury and illness recordkeeping requirements, and there is deep concern it will lead to less complete and accurate reporting of work-related injuries and illnesses.

5 Industries exempted from OSHA injury and illness recordkeeping requirements are those that have a rate of injuries resulting in lost workday, restricted activity, or job transfer that is less than 75 percent of the national average, as calculated over a 3-year period. All employers, regardless of exemption for any reason, must report to OSHA any workplace incident that results in a fatality, in-patient hospitalization, amputation, or loss of an eye (29 CFR

From 1996 to 2011, the OSHA Data Initiative (ODI) collected, analyzed, and disseminated summary information on work-related illnesses and injuries from employers within specific industries and with specific-size workforces (OSHA, 2017d). These data were used to determine injury and illness rates that were establishment-specific; furthermore, when combined with other data sources these data were used to target enforcement and compliance assistance activities (OSHA, 2017i).

In 2017, a new electronic reporting system was scheduled to be implemented to provide online submission of the standard employer data on injury and illnesses under a new OSHA regulation issued in 2016 (OSHA, 2017f). This electronic injury reporting system is similar to the OSHA Data Initiative but covers a larger number of employers and requires the submission of more detailed injury and illness information from larger employers. The electronic reporting system, like the ODI, includes a number of employers that are also are part of the BLS SOII sample and required to report similar injury and illness data separately to both OSHA and BLS, since BLS cannot share the establishment specific data it collects under CIPSEA with OSHA. As will be discussed in Chapter 6, this results in duplicate reporting by a large number of employers. Accordingly, OSHA and BLS are evaluating how to best address this issue.

OSHA, through standards for toxic materials and harmful physical agents issued under Section 6(b)(5) of the OSH Act, also requires employers to conduct exposure monitoring and to provide medical surveillance of workers in jobs covered by its agent-specific standards. Currently, there are about 30 agent- or hazard-specific standards that require periodic exposure monitoring or medical examinations (OSHA, 2014). In addition, OSHA’s regulation on Access to Employee Exposure and Medical Records (29 CFR 1910.1020) requires employers to maintain exposure and medical records produced under these standards as well as other exposure and medical records, and to provide these records to employees. OSHA and NIOSH also have a right of access to this information, but there is no requirement for employers to report this exposure or medical information to the agencies (see Figure 3-1).6

OSHA also conducts exposure monitoring as part of its health compliance inspections. The sampling results include data on personal, area, and bulk samples for a wide variety of air contaminants. OSHA has developed a Chemical Exposure Health Data website where the OSHA sampling da-

___________________

§1904.39). The list of industries exempted from routine injury recordkeeping requirements can be found online (OSHA, 2017e).

6 Work-related illnesses that are required to be recorded under OSHA’s injury and illness recordkeeping requirements will have to be reported to OSHA under the new electronic reporting requirements.

tabase from 1984 to 2015 can be searched or downloaded in its entirety (OSHA, 2017g).

NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH

Created in 1970 through the OSH Act, NIOSH was charged with carrying out the Secretary of Health and Human Services’ responsibilities under that law. This agency operating under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is charged in Sections 20 and 21 of the OSH Act to conduct research, experiments, and demonstrations relating to occupational safety and health; to develop criteria for recommended standards; and to conduct education programs to “provide an adequate supply of qualified personnel to carry out the purposes of this Act (Section 21).” In Section 24, the statistics section, NIOSH is given a consultative role to provide input to the Secretary of Labor to “develop and maintain an effective program of collection, compilation, and analysis of occupational safety and health statistics.” NIOSH is also charged to work in cooperation with the Department of Labor on the development of injury and illnesses recording and reporting regulations.

Under the Mine Safety and Health Act, NIOSH has specific responsibilities related to mine safety and health. NIOSH is charged with conducting research to assess adverse health effects, to develop control technologies to address for mine safety and health hazards, and to make recommendations to the MSHA for improvements in mine safety and health standards. NIOSH also oversees the Coal Workers’ Health Surveillance Program, which it has administered since its inception in 1970, to “prevent early coal workers’ pneumoconiosis from progressing to a disabling disease. Through the program, eligible miners can obtain periodic chest radiographs (NIOSH, 2017).

NIOSH’s 2016-2020 strategic goals and objectives include to “track work-related hazards, exposures, illnesses and injuries for prevention” (NIOSH, 2016). To identify research priorities NIOSH applies an approach based on assessing burden, need, and impact. Surveillance data are a key element to this process.

Since 1996, NIOSH has organized much of its work through the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA). The first decade of NORA was organized around 21 “focus” areas organized in three categories: diseases and prevention, work environment and exposures, and research tools and approaches. In the second decade the agenda was organized on 10 industry sectors, and beginning in the third decade (2016) 7 health-based cross-sectors (e.g., hearing loss prevention and respiratory health) were added to the 10 industry sectors. Surveillance is considered as a crosscutting

concern relevant to all sectors and health outcomes, and NIOSH uses an industry-health outcome matrix in surveillance planning.

Recognizing that the SOII is not a good source of information on chronic occupational diseases, the 1987 NRC report recommended that NIOSH be “the lead agency having the responsibility for the development of a comprehensive occupational disease surveillance system that would include the compilation, analysis, and dissemination of occupational illness data. . . . To accomplish this, NIOSH should request, and Congress approve, appropriation of additional funds” (NRC, 1987, p. 108). While the funding has not been made available to fulfill this recommendation, NIOSH has undertaken a number of surveillance activities to generate information not available through either the SOII or the CFOI.

NIOSH currently has a multipronged strategy to address disease and injury surveillance needs that includes

- Leveraging existing surveys and data systems managed by other agencies,

- Building occupational health surveillance capacity at the state level,

- Incorporating industry and occupation into existing surveys and other data systems,

- Improving the capacity and accuracy of autocoding tools essential to fully implement the above strategies, and

- Accelerating communication for prevention (Schnorr, 2016).

NIOSH efforts in surveillance include ongoing surveillance activities as well as surveillance research aimed at developing new tools and methods or more in-depth analyses of surveillance data (see Chapter 4). Intramural researchers apply through a competitive application process for funds to conduct surveillance research. In addition, NIOSH funds multiple states and universities to conduct surveillance and surveillance research through its extramural program.

As described in greater depth in Chapters 4 and 6, NIOSH works collaboratively with state and federal partners to implement, support, and build on existing population-based data sources, thereby strengthening the population-level data needed to provide nationwide insights on worker safety and health. Additionally, NIOSH supports a range of case-based surveillance programs focused on mortality or specific illnesses or industries that warrant more immediate action and/or follow-up to more fully characterize the problems (e.g., the Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation Program and the Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance Program [ABLES]). In the past, NIOSH conducted surveys to collect data on occupational exposures to chemical, physical, and biological hazards in

a representative sample of workplaces nationwide.7 Two more recent hazard surveillance efforts focused on a web-based survey of hazards in health care settings (see Chapter 5) and collecting a limited amount of information about work organization, psychosocial, and nonspecific information about common workplace chemical and physical agent exposures and other common workplace hazards through the National Health Interview Survey (NIOSH, 2015). Efforts are under way by NIOSH and partner organizations to continue to refine and harness health-related and information technologies (e.g., electronic health records and tools for assigning standardized codes to narrative text) to improve data on work-related injuries and illnesses, to make data available to other stakeholders, and to effectively disseminate timely surveillance findings (see Chapters 4 and 6).

In addition to its core surveillance activities, NIOSH engages in other activities that can assist with surveillance efforts. NIOSH conducts health hazard evaluations which provide useful information about workplace exposures and related health impacts. NIOSH also develops and disseminates hazard alerts, sometimes jointly with OSHA, to provide information about recently identified occupational health and safety problems and exposures of particular concern, and recommend controls measures.

MINE SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

MSHA was established by the Mine Safety and Health Act (P.L. 95-164) in 1977. The agency develops and enforces safety and health rules for all mines in the United States—coal, metal, and nonmetal; underground and surface—regardless of size, number of employees, commodity mined, or method of extraction (MSHA, 2017a). MSHA regulations (30 CFR Part 50) require “mine operators to immediately notify MSHA of accidents, require operators to investigate accidents, and restrict disturbance of accident-related areas. The regulations require operators to file reports with MSHA pertaining to accidents, occupational injuries, and occupational illnesses, as well as employment and coal production data” (MSHA, 2017b). MSHA also is obligated to inspect all underground mines four times a year and all surface mines twice a year for safety and health compliance.

Coal mine operators are also required to conduct regular monitoring and reporting of coal dust exposures. MSHA maintains a comprehensive Mine Data Retrieval System accessible on the MSHA webpage that provides detailed mine-by-mine data for all mines and contractors (MSHA, 2017c). This database is also available with detailed information in a single file for health data; injury, illness, and fatality data; exposure data; results of industrial hygiene sampling data; and inspection data.

___________________

7 National Occupational Hazard Survey (1972-1974), National Occupational Exposure Survey (1981-1983), and National Occupational Health Survey of Mining (1984-1989).

OTHER FEDERAL AGENCIES

A number of other federal agencies have statutory responsibilities for occupational and public safety and health oversight for specific industries, operations, or hazards. Under section 4(b)(1) of the OSH Act, except where provided by statute or interagency agreement, OSHA does not overlap OSH responsibilities with these other agencies (Dale and Shudtz, 2013). In the transportation sector, the Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Railroad Administration, and Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration respectively regulate and provide oversight in the aviation, rail, and trucking industries. In the maritime sector, the Coast Guard is responsible for occupational safety and health on the high seas and on the outer continental shelf, and the Department of the Interior provides safety oversight on offshore drilling platforms.

The Department of Energy (DOE) enforces safety and health at the DOE national laboratories and weapons plants and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has responsibility for the safety of employees exposed to nuclear materials at nuclear power plants. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has occupational safety and health responsibilities under the statutes it administers. The protection of farmworkers and applicators from pesticide exposures is governed by the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (P.L. 61-152). Under the Toxic Substances Control Act (P.L. 94-469), workers are one of the populations to be protected from the health risks from toxic chemical exposures.

In addition to providing regulatory and enforcement oversight for worker safety, many of these agencies collect data and implement surveillance systems. For example, the Federal Railroad Administration requires reporting of occupational injuries and illnesses by rail operators. EPA requires the reporting of safety and health studies, data, and notices of substantial risk, and maintains an inventory of chemicals that are manufactured in and imported into the United States.

A number of other federal agencies also collect data and conduct surveillance activities relevant and useful to OSH surveillance but are not employer or establishment based. Among these are many other centers and programs within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (e.g., the National Center for Health Statistics, the National Program of Cancer Registries, and the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (see Box 3-1 and Chapters 4 and 6).

Given the large number of agencies, data sources, and systems, with relevant data there are great challenges in ensuring that the data are collected in a manner that allows their use for broader OSH surveillance purposes.

STATE AGENCIES

State agencies have the potential to play a pivotal role in OSH surveillance. While national surveillance is essential to set national prevention and research priorities and inform federal policy development, state-specific occupational health and safety problems can be obscured in national statistics,

making state-based surveillance an essential supplement to national surveillance. With advances in information technology, there are an increasing number of state health data sources useful for tracking work-related injuries and illnesses that can provide both case-level and population-based information not available through systems overseen by BLS (see Box 3-2). These include, among others, hospital discharge records, laboratory reports,

medical records, poison control data, and workers’ compensation data. State agencies in a limited number of states have used these data sources both to generate timely, locally relevant information and to help fills gaps in surveillance at the national level. State agencies are also uniquely positioned to use the data directly to improve worker safety and health. Again in a limited number of states, states have responded to identified OSH concerns by collaborating with community partners—employers and trade associations, unions and worker centers, health care providers, and other community organizations—as well as federal and state OSHA and other government agencies to translate surveillance findings into preventive action.

OSH surveillance activity and agency leadership in OSH surveillance at the state level varies from state to state. About half of the states have state-based OSH surveillance programs with epidemiologic expertise to conduct surveillance (NIOSH, 2012). Most are based in state public health departments with a few located in labor departments or in universities that serve as the bona fide agents for state public health agencies. Only about 20 percent of states have substantial OSH surveillance capacity (CSTE, 2013). Almost all states, usually state labor departments, partner under contract with BLS to collect data for the BLS CFOI and SOII programs.

In the United States, non-work-related public health surveillance is a collaborative federal-state endeavor. State public health agencies have the legal authority to require disease reporting and forward the data to CDC with personal identifiers removed. National data on chronic and communicable disease disseminated by CDC depend on the state’s legal authority and activity to collect the data. This state activity is performed with substantial federal support to all 50 states. Historically, public health surveillance was focused primarily on surveillance of communicable diseases, but has expanded in recent decades to track other health outcomes, such as cancer and violent deaths and to a more limited extent work-related injuries and illnesses. Many states have legal authority to either initiate or expand occupational disease surveillance activity (Freund et al., 1990). Some state health agencies, largely with funding from NIOSH, have built on this authority to develop case- and population-based occupational injury or illness surveillance systems and carry out related intervention and prevention activities.

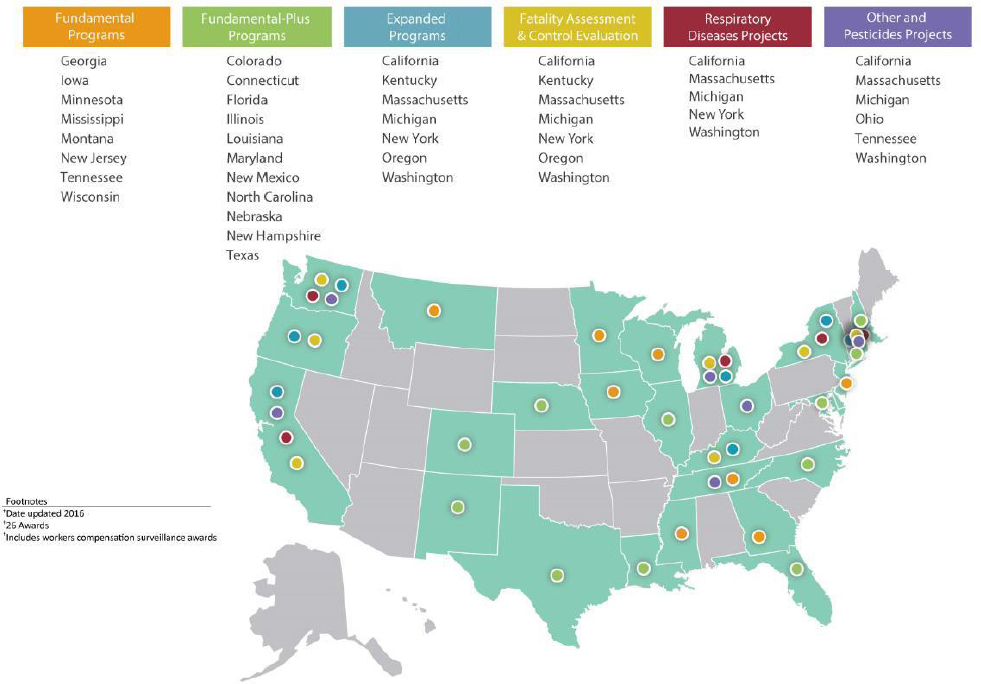

As of 2017, NIOSH provides funding through a competitive funding process to 27 states, largely to public health agencies to conduct OSH surveillance and to promote the use of the data for action to address identified health and safety problems (see Figure 3-2). Twenty six states receive limited “fundamental” support for capacity building in occupational public health. At minimum, these states are working to generate the standardized occupational health indicators and build working relationships for prevention with OSH and other state public health stakeholders (Thomsen et al.,

2007; Stanbury et al., 2008). Seven states conduct “expanded” surveillance activities focused on targeted health outcomes, industries, or populations.8 Some state OSH surveillance programs also partner with other public health programs to develop more comprehensive approaches to problems, such as indoor air and chemical exposures in schools, distracted driving, infectious diseases, and, more recently, opioid overdoses, that can affect workers and the general public alike (Davis and Souza, 2009). Five states are also supported by NIOSH specifically to increase the state’s capacity to use workers’ compensation data for prevention, providing epidemiological expertise and a focus that is frequently lacking in state agencies that administer these systems (see below and Chapter 6). State OSH programs can also serve as important bridges between labor and public health agencies within the states that have overlapping responsibilities to protect the health of the population, although the level of such interagency collaboration varies widely by state.

Workers’ compensation programs are another source of state-based injury and illness information (see Chapter 4 and 6). Workers’ compensation provides no-fault medical and income replacement benefits to workers injured on the job while protecting employers from liability lawsuits for such injuries. For work-related fatalities, family members may receive compensation. Most states have had workers’ compensation laws in effect since the 1910s to 1920s (Sengupta and Baldwin, 2015). The National Academy of Social Insurance estimates that workers’ compensation programs covered 132.7 million U.S. workers in 2013, approximately 91 percent of the 146 million civilian workers in 2014 (Baldwin and McLaren, 2016).

Data from workers’ compensation cases have the potential to provide insights into trends in occupational safety and health (see Chapter 6). However, there is wide variation across the states in the nature and extent of data that are collected, including differences in the definition of reportable conditions, the type of data collected, data accessibility, and data-validation methodologies, creating significant challenges in using such data for national OSH surveillance.

EMPLOYEES, EMPLOYERS, AND OTHER STAKEHOLDERS

While public health surveillance is primarily a function of government agencies, employers, employees, and other stakeholders also collect and use data to improve worker health and safety.

As noted above, OSHA requires companies in covered industries to maintain logs of work-related injuries and illnesses. Additionally, a number

___________________

8 EPA contributes funding for pesticide surveillance in some states and the CFOI program is conducted by health agencies in several additional states.

of OSHA standards require employers in workplaces where regulated hazards are present to monitor exposure levels of workers. In many larger workplaces, employers implement safety and health programs, which utilize injury, illness, and exposure data to identify hazards and to take corrective action for prevention. Safety and health programs need meaningful participation of employees to be effective and are strongly recommended by federal OSHA (OSHA, 2016b) and many safety and health organizations (OSHA, 2017h). Some are required by a number of state OSHA plans, including California and Minnesota (OSHA, 2012). Recommended best practices for health and safety programs include collection, review, and use of data on work-related injuries, illnesses, and hazards for both hazard identification and performance monitoring.

To further promote and improve worker safety and health, some companies go beyond the basic regulations to focus on how best to identify potential hazards in their specific area of work and to track their safety record. Some companies conduct extensive surveillance, linking OSHA injury records with medical reports, workers’ compensation reports, and other data to identify hazards and emerging problems and to track progress. For example, the Ford Motor Company, with the cooperation and involvement of the UAW (United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America), developed an integrated safety and health surveillance system that captures and codes every case from the medical department, OSHA logs, and incident investigations. The corporate-wide data system allows detailed analysis by plant and department, type and source of injury, and other criteria (Reeve, 2016).

In the construction industry, information on injuries, illnesses, and workers’ compensation is used by contracting entities and project managers to assess the qualifications of contractors and subcontractors and to monitor project safety and health performance. Harvard University developed a database of the safety and health records of all the contractors and subcontractors working on its construction projects and a software system for tracking and analysis. The safety surveillance system now also provides services to other outside companies to help manage the safety and health oversight of their construction activities (Burke, 2016). In the commercial construction industry, many large general contractors centralize OSHA log data for all subcontractors onsite.

Despite these positive examples, it has often been challenging to engage the employer community and to encourage them to participate voluntarily in surveillance systems such as those discussed in this report. Many are reluctant to provide information to government entities given their experience with, and reservations about, the current OSH surveillance processes. The existing need to gain employer trust and engagement became clear as the committee heard testimony indicating that some employers were dissatisfied

with the agencies and their current processes, questioning agency assertions that the regulatory requirements are aimed at trying to help employers to improve safety in the workplace. Some employers perceive the relationship with the agencies as adversarial rather than collaborative, characterizing the regulations as too often being coercive, focusing on enforcement and perceived “shaming” of employers rather than on developing novel methods to help employers and employees to understand the true root causes of an injury or illness. Some express concern that the agencies have based their actions on scientific literature that is biased in favor of their preferred methods and outcome while questioning the validity and credibility of employer-sponsored research.

Notwithstanding these doubts, employers welcome a smarter, better coordinated, and more cost effective set of surveillance approaches that provides useful, timely information to employers about their workplaces while recognizing and respecting current or additional privacy and confidentiality protections. A system that helps foster greater participation by the workforce, employers, and the community at large would also likely be more attractive to employers. The committee has accordingly considered these issues and offered findings, conclusions, and recommendations that are intended to support the development of optimal trust and confidence between the regulatory agencies and employers.

An example of such an approach to compliance that is supported by some employers is the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA's) “Just Culture” approach (Reason, 1997; GAIN, 2004). In the 1990s, a “no blame culture” had developed in an effort to replace the largely punitive safety culture that it had sought to replace and it acknowledged that many unsafe acts were “honest errors.” However, this no blame approach failed to address those who willfully engaged in unsafe behavior or address culpability (GAIN, 2004). The “Just Culture” notion differs from the “no blame culture” in that the former stresses that safety compliance and prevention would be based on a problem-solving approach (i.e., engagement, root-cause analysis, transparency, and information exchange) in which the primary goal is to enhance the safety performance of the individual and organization and where finding fault or penalizing noncompliance is a secondary concern. Such methods, however, do require agencies to confront individuals or organizations that willfully and sometimes repeatedly engage in practices that observers would recognize as being likely to increase the risk of a bad outcome. This also requires a clear and accepted method for distinguishing between culpable and nonculpable unsafe acts. The goal of such an approach is to create a trusted culture that encourages and even rewards people for identifying and sharing safety-related information.

Workers groups and unions are also important partners in data collection and analysis and utilization. For example, CPWR—The Center

for Construction Research and Training, affiliated with North America’s Building Trades Unions—conducts research, training, and service programs in the construction industry (CPWR, 2017). CPWR serves as the National Construction Research Center for NIOSH and through a NIOSH cooperative agreement conducts research to identify existing and emerging hazards and to develop evidence-based technologies and work practices to prevent injuries and illnesses. As part of its work, the center produces The Construction Chart Book, which presents extensive analysis of data on construction safety and health and other facets of the U.S. construction industry with creative use of publicly available information including economic, demographic, employment and income, and education and training data (CPWR, 2013).

Worker groups and unions regularly utilize injury, illness, and fatality information to seek changes in safety and health practices and stronger safety and health regulations and laws. For example, in Massachusetts, following the deaths of several Vietnamese floor refinishers, the Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health and the Vietnamese American Initiative for Development partnered with state and local agencies and industry groups to educate workers, employers, and consumers about the fire hazards of certain floor refinishing products and to stop the use of these products (MA COSH, 2005). These efforts ultimately resulted in new state regulations on floor refinishing product content.

FEDERAL AND STATE AGENCY COORDINATION, COLLABORATION, INFORMATION EXCHANGE, AND PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ON OSH SURVEILLANCE

Ideally, the OSH surveillance activities of BLS, OSHA, NIOSH, other federal agencies, and state agencies would be carried out under the framework of a national OSH surveillance strategy and through a unified surveillance system, with close coordination and collaboration on the development of strategy, planning, implementation, and evaluation. However, currently there is no overall strategy, single system, or overall formal body responsible for coordination or integration of OSH surveillance activities and programs. Just as there are a wide variety of different types of data collection and surveillance activities being conducted across agencies and organizations, there are a wide variety of mechanisms and means for coordination and collaboration among and between the agencies and from stakeholder and public input. In response to a query from the committee, BLS, NIOSH, and OSHA provided examples of coordinating activities that are summarized in the following section.

Coordination Among BLS, OSHA, NIOSH, and Federal Agencies

BLS has some formal mechanisms for coordinating programs and work with other agencies, but according to the agency much of this work is informal. BLS provides OSHA a formal briefing the day before releasing the annual fatality and injury and illness reports. Both OSHA and NIOSH are provided a copy of the CFOI research file each year.

BLS and NIOSH have worked together informally on a number of joint surveys, such as the survey on workplace violence prevention, and research papers. For example, BLS and NIOSH staff recently collaborated with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) on a peer-reviewed article describing a methodologic approach to matching CFOI data with NHTSA’s Fatality Analysis Reporting System. BLS has also provided technical assistance to NIOSH on the development of an occupational autocoding tool and has worked closely with OSHA on the development of their data-capture tools for OSHA’s electronic injury reporting initiative.

OSHA and NIOSH also have both formal and informal mechanisms for collaboration and information sharing. Through the NIOSH-OSHA Liaison Information Exchange, OSHA and NIOSH staff regularly discuss topics of current concern and technical issues. OSHA and NIOSH are also members of an interagency committee that includes OSHA, MSHA, NIOSH, EPA, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences that meets twice a year to share information and coordinate activities on proposed rules, risk assessments, and risk management strategies for controlling exposures to toxic agents.

OSHA, BLS, and NIOSH also have data-sharing arrangements. For example, OSHA provides the BLS CFOI program with quarterly files of fatalities investigated, and NIOSH and OSHA have an agreement under which NIOSH has access to OSHA’s Information System and OSHA to ABLES data.

As discussed above, it is BLS policy to treat the microdata it collects under the SOII and CFOI as subject to the confidentiality provisions of CIPSEA. Thus this microdata are only shared with OSHA, NIOSH, and other federal agencies, subject to the same terms of confidentiality, greatly restricting and limiting the use of the BLS collected injury and illness data for surveillance, intervention, and prevention purposes.

Coordination and Collaboration Among NIOSH and Other CDC and HHS Agencies

Underlying the accomplishments and challenges in current OSH surveillance efforts is the relationship between NIOSH and CDC. As described, NIOSH was created by the Occupational Safety and Health Act

of 1970 as an agency in the Department of Health and Human Services charged with carrying out the responsibilities of the Secretary of HHS under the Act. It was administratively established as part of the CDC, the agency which has the primary responsibility for carrying out the federal government’s public health functions. But the “fit” between NIOSH and CDC has always been a bit strained. The Act created NIOSH as a sister agency to OSHA, with responsibility to provide recommendations and support to the Department of Labor for carrying out regulatory activities, data collection, and statistical functions. NIOSH has often been viewed as an adjunct of OSHA and DOL, not a public health agency, and worker safety and health seen largely as a responsibility of the Department of Labor. Consequently, occupational health is not viewed by all as a “public health” issue and has not been effectively integrated into general public health either at the national or state level. Occupational health and occupational health surveillance have remained low priorities in the general public health community, including within CDC. Funding and support for occupational health surveillance has been limited. Historically, it has been difficult for NIOSH to integrate occupational safety and health into other CDC and HHS programs, and occupational health and safety has not received strong support from HHS or CDC.

In recent years NIOSH has made some strides to initiate increased collaboration and activity with other CDC and HHS agencies in a wide range of surveillance programs and activities. NIOSH is a participant in several CDC-wide surveillance groups, including CDC’s Surveillance Leadership Board, CDC’s Surveillance Data Platform Workgroup, which works to make essential surveillance systems more adaptable to changes in technology, knowledge, and stakeholders (including states); and CDC’s Surveillance Science Advisory Group.

NIOSH also collaborates with other CDC centers to integrate occupational safety and health-related issues into broader surveillance activities. For example, NIOSH is working with the CDC’s Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services (CSELS) and the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases to include industry and occupation as a standard set of data in the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. NIOSH continuously collaborates with the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), most recently in the inclusion of an occupational health supplement in the 2015 National Health Interview Survey and the Asthma Supplement in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) designed to collect data on work-related asthma. NIOSH also collaborates closely with the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC), participating in biannual meetings and cross-reviewing articles of common interest prior to publication. NIOSH and NCIPC both provide funding to the Consumer Product Safety Com-

mission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), which enables both programs to obtain more complete data from NEISS than would be possible otherwise. Additionally, the NIOSH Electronic Health Record Working Group participates in national efforts by CSELS, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, and external partners (e.g., the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists [CSTE]9) to establish end-to-end occupational case data collection from electronic health records.

BLS, OSHA, and NIOSH Collaboration and Coordination with State Agencies

BLS, OSHA, and NIOSH have established relationships with state agencies that, among other efforts, work to carry out OSH data-collection and surveillance activities. BLS’s primary collaboration is through its agreements with state partners to collect and analyze data for the SOII and CFOI. As resources permit, BLS holds a national conference with state partners and participates in annual meetings with NIOSH-funded state-based surveillance programs and CSTE.

Through OSHA’s formal relationship with the 26 OSHA state plan states, the states input their inspection data into the OSHA Information System, creating a unified national database with inspection and violation data and severe injury and fatality reports. Several public health and workers’ compensation agencies in individual states have developed close working relationships with state and federal OSHA programs. For example, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services requires hospitals and emergency departments to report work-related injuries. The department reviews the medical records of the injuries and regularly makes referrals to the Michigan OSHA program to conduct follow-up inspections on workers who have amputations, burns, and skull fractures (Kica and Rosenman, 2012, 2014; Largo and Rosenman, 2015). In Massachusetts, Region I of federal OSHA, which covers the New England states, receives reports of amputations from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, which may result in follow-up or inspections. In Region VII, the Omaha, Nebraska Area OSHA office receives a regular feed of workers’ compensation cases from the Nebraska Workers’ Compensation Court, which is used in targeting enforcement inspections under a local emphasis program.

___________________

9 CSTE is a national organization of state, local, tribal, and territorial epidemiologists. It plays a key role nationally in developing national definitions for use in surveillance and determining which reportable health conditions are to be reported voluntarily to CDC. It supports effective public health surveillance and good epidemiological practice through training, capacity development, and peer consultation and by promoting collaboration between federal and state surveillance programs.

NIOSH provides both financial and technical support to state agencies for OSH surveillance activities and plays an active role in fostering coordination and collaboration (CSTE, 2011). Since 1998, NIOSH has engaged CSTE to provide a mechanism for collective state input to NIOSH’s OSH surveillance planning and to facilitate surveillance capacity building and collaboration among the states, including building regional networks of states conducting surveillance. CSTE holds biannual meetings with the state-based OSH surveillance programs, including not only funded states but other states interested in building programs. CSTE also hosts ad hoc meetings bringing state OSH surveillance programs and federal agencies together to address specific topics such as collaborations with OSHA, use of BLS data systems, and closing the gaps in surveillance.

NIOSH holds periodic working meetings with states conducting expanded surveillance of NIOSH priority conditions including work-related lung disease, pesticide illness and injury, fatal injuries, and adult lead exposures. State collaboration with NIOSH intramural scientists conducting surveillance research focused on other topics is less robust. NIOSH is also working with CSTE to establish regional networks of states to build surveillance and prevention capacity in states that currently lack programs.

NIOSH has a Surveillance Coordinating Group led by the director of one of the NIOSH divisions that coordinates surveillance activities across the agency. CSTE has a state representative that participates in this group. Representatives from state programs also serve on the NIOSH Board of Scientific Counselors and NORA industry-sector councils.

In sum, there is strong collaboration between NIOSH and state-based surveillance programs that could be enhanced with additional state collaboration with NIOSH intramural researchers. State public health collaboration with the national OSHA and BLS offices has increased in recent years but remains largely informal (outside of several BLS-funded surveillance research grants to states). Collaboration with regional OSHA and BLS offices varies widely by state.

BLS, OSHA, NIOSH, and State Agency Collaboration with Stakeholders and Public Engagement

BLS, OSHA, NIOSH, and state agencies seek to engage stakeholders and the public through a variety of ways. BLS receives regular feedback through the BLS Data Users Advisory Committee, a formal advisory committee “that provides advice to BLS from the points of view of data users from various sectors of the U.S. economy, including the labor, business, research, academic, and government communities, on matters related to the analysis, dissemination, and use of the Bureau’s statistics, on its published reports, and on gaps between or the need for new Bureau statistics” (BLS,

2016b). BLS also actively seeks input from the safety and health community via the CSTE, the American Public Health Association, and others. Many of the recent changes in BLS’s OSH statistics program have been driven by stakeholder input including the development of a CFOI web-scraping utility, the pilot-testing of a household survey of occupational injuries and illnesses, and the placement of SOII data in the Federal Statistical Research Data Centers (see Chapter 4).

OSHA seeks and receives stakeholder input on its major data-collection activities through the formal mechanisms established under the Paperwork Reduction Act. In addition, the collection and submission of safety and health information by employers is established by regulations, which require public notice and comment. For example, OSHA’s expansion of its injury and illness reporting requirements for both severe injury reporting and electronic injury reporting were implemented through regulations for which OSHA gathered extensive input from stakeholders and the public, receiving both written comments and holding public meetings. NIOSH has formal and informal methods of obtaining stakeholder input on surveillance activities, including the NORA industry-sector and cross-sector councils, which reflect a mix of internal and external stakeholders.

Many of the state OSH surveillance programs are actively engaged with industry, labor, and other community stakeholders at the state and local levels. Some states have active program-wide advisory boards that serve as a means for obtaining ongoing stakeholder input on program activities. States also create stakeholder working groups as needed to address specific topics identified through surveillance such as injuries associated with patient handling among hospital workers in Massachusetts, injuries among workers in the logging industry in Washington State, and injuries to workers in the construction industry in California (Harrington et al., 2009; WA DLI, 2013; MA DPH, 2014).

UPDATES ON THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE 1987 REPORT

The committee reviewed the 1987 NRC report, Counting Injuries and Illnesses in the Workplace: Proposals for a Better System, and asked the relevant federal agencies to provide an update on their progress in responding to the recommendations made in that report. In the 30 years since that report, there have been significant improvements and advances in OSH data collection and surveillance. A table outlining the recommendations and actions and developments in response to that report is included in Appendix D.

Significant developments include the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, the expansion of the SOII to collect case and demographic information, and extensive research to assess and document

the undercount of work-related injuries and illnesses in the SOII. OSHA instituted the OSHA Data Initiative to collect establishment-specific injury data to target inspections to the most hazardous workplaces, recently supplanted by the electronic injury reporting initiative, and has entered the exposure monitoring data collected during inspections into a publicly available database. OSHA has also implemented a new severe-injury reporting system. NIOSH has provided funding for some states to conduct surveillance of key injuries and diseases and partnered with other health agencies to conduct surveys and enhance use of existing data sources to gather information on occupational injuries and health conditions.

However, on several of the recommendations made in the 1987 report, there has been little or no progress. The recommendation for BLS to provide regular feedback to employers on the results of the BLS survey in order to benchmark performance and the recommendation to OSHA to require employer reporting of exposure monitoring data for specific substances have not been implemented. The development of a comprehensive occupational disease surveillance system with NIOSH as the lead agency has not been pursued as funding has not been available. Furthermore, OSH surveillance in most states remains at the capacity building level given the lack of recognition of OSH surveillance as a core public heath function and the attendant lack of resources.

Overall, the state of OSH surveillance has improved since the 1987 report, but significant gaps and barriers to achieving comprehensive OSH surveillance remain.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Occupational safety and health surveillance in the United States is a collaborative, decentralized effort carried out by a large number of federal and state agencies with the substantial involvement of BLS, OSHA, NIOSH, MSHA, and state health and labor departments. A broad range of stakeholders including employers, employees, and safety and health professionals also participate. The data and information that are collected and utilized come from many different sources, ranging from workplace-based reporting by employers, to individual case reports by physicians, to population-based health surveys.

OSH surveillance represents a prime example of the difficulties of generating and using data for science, policy, and public information that is posed by our decentralized federal statistical system.

Conclusion: While there is some coordination and collaboration among and between different agencies engaged in OSH surveillance, much of the agency interaction is limited to information exchange rather than joint collaborative programs and initiatives. Collecting SOII and CFOI data under

CIPSEA greatly limits the sharing and use of these data for surveillance purposes by other federal and state agencies. It would be worthwhile for BLS, OSHA, and NIOSH to jointly explore if there are alternative arrangements for collecting and sharing establishment specific injury and illness data to make the data more widely available and useful for surveillance and prevention purposes and to also avoid duplicate reporting. An example of one such arrangement could be for OSHA to collect the data from employers and provide the data to BLS for statistical analysis and to NIOSH for research and surveillance purposes.

Conclusion: While significant improvements in OSH surveillance have occurred since the 1987 report, significant gaps remain as OSH surveillance in the United States remains highly fragmented with no overall unified surveillance strategy or mechanism for planning, coordinating, or executing programs. In the chapters that follow, a detailed review of the current systems, existing gaps and barriers, promising developments, and recommendations for a 21st-century OSH surveillance system are presented.

REFERENCES

Baldwin, M. L., and C. McLaren. 2016. Workers’ Compensation: Benefits, Coverage, and Costs, 2014. Washington, DC: National Academy of Social Insurance. Available online at https://www.nasi.org/sites/default/files/research/NASI_Workers_Comp_Report_2016.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2015. A look at violence in the workplace against psychiatric aides and psychiatric technicians. Monthly Labor Review. Available online at https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/pdf/a-look-at-violence-in-the-workplace-against-psychiatric-aides-and-psychiatric-technicians.pdf (accessed November 8, 2017).

BLS. 2016a. Injuries from falls to lower levels, 2013. Monthly Labor Review. Available online at https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2016/article/pdf/injuries-from-falls-to-lower-levels-2013.pdf (accessed November 8, 2017).

BLS. 2016b. Data users advisory committee charter. Available online at https://www.bls.gov/advisory/duaccharter.htm (accessed June 23, 2017).

BLS. 2017. Confidentiality of data collected by BLS for statistical purposes. Available online at https://www.bls.gov/bls/confidentiality.htm (accessed November 8, 2017).

Burke, G. 2016. Contractor performance measurement. Presentation to the National Academies Committee on Developing a Smarter National Surveillance System for Occupational Safety and Health in the 21st Century, September 21. Available online at https://vimeo.com/187718133 (accessed July 10, 2017).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017a. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html (accessed June 23, 2017).

CDC. 2017b. What is PRAMS? Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/prams/index.htm (accessed June 23, 2017).

CPWR (The Center for Construction Research and Training). 2013. The Construction Chart Book, 5th Ed. Available online at http://www.cpwr.com/publications/construction-chart-book (accessed March 25, 2017).

CPWR. 2017. About CPWR. Available online at http://www.cpwr.com/about/about-cpwr (accessed March 25, 2017).

CSTE (Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists). 2011. Guidance: public health referrals to OSHA. Available online at http://www.cste2.org/webpdfs/occupational/OSHAreferral922011.pdf (accessed May 26, 2017).

CSTE. 2013. National assessment of epidemiology capacity: Findings and recommendations. Available online at http://www.cste2.org/2013eca/CSTEEpidemiologyCapacityAssessment2014-final2.pdf (accessed September 4, 2017).

Dale, G. N., and P. M. Shudtz, eds. 2013. Occupational Safety and Health Law, 3rd Ed. Arlington, VA: American Bar Association and Bloomberg BNA.

Davis, L., and K. Souza. 2009. Integrating occupational health with mainstream public health in Massachusetts: An approach to intervention. Public Health Reports 124(Suppl 1):5-14.

Drudi, D. 2015. The quest for meaningful and accurate occupational health and safety statistics. Monthly Labor Review. December 2015. Available online at https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/the-quest-for-meaningful-and-accurate-occupational-health-and-safety-statistics.htm (accessed January 19, 2017).

Freund, E., P. J. Seligman, T. L. Chorba, S. K. Safford, J. G. Drachman, and H. F. Hull. 1990. Mandatory reporting of occupational diseases by clinicians. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 39(RR-9):19-28.

GAIN (Global Aviation Information Network). 2004. A Roadmap to a Just Culture: Enhancing the Safety Environment. Flight Operations/ATC Operations Safety Information Sharing Working Group, Global Aviation Information Network (GAIN). Available online at https://flightsafety.org/files/just_culture.pdf (accessed January 19, 2017).

Harrington, D., B. Materna, J. Vannoy, and P. Scholz. 2009. Conducting effective tailgate trainings. Health Promotion Practice 10(3):359-363.

Inserra, S. 2016. Presentation at the NIOSH-State Partners Meeting, December 7, 2016, Atlanta, GA.

Kica, J., and K. D. Rosenman. 2012. Multi-source surveillance system for work-related burns. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 54(5):642-647.

Kica, J., and K. D. Rosenman. 2014. Multi-source surveillance system for work-related skull fractures in Michigan. Journal of Safety Research 51:49-56.

Largo, T. W., and K. D. Rosenman. 2015. Surveillance of work-related amputations in Michigan using multiple data sources: Results for 2006-2012. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 72:171-176.

MA COSH (Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health). 2005. Protecting workers and homeowners from wood floor-finishing hazards. Available online at http://www.masscosh.org/files/ProtectingFromFloorFinishingHazards.pdf (accessed March 25, 2017).

MA DPH (Massachusetts Department of Public Health). 2014. Moving into the future: Promoting safe patient handling for worker and patient safety in Massachusetts hospitals. Available online at http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/occupational-health/ergo-sph-hospitals-2014.pdf (accessed June 19, 2017).

MSHA (Mine Safety and Health Administration). 2017a. Mission. Available online at https://www.msha.gov/about/mission (accessed March 20, 2017).

MSHA 2017b. Part 50 reports: Mining industry accident, injury, illness, employment, and coal production reports. Available online at https://www.msha.gov/data-reports/reports (accessed March 30, 2017)

MSHA. 2017c. Mine data retrieval system. Available online at https://arlweb.msha.gov/drs/drshome.htm (accessed March 30, 2017).

NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics). 2015. About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm (accessed June 23, 2017).

NCHS. 2016. About the National Health Interview Survey. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm (accessed June 23, 2017).

NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health). 2012. Surveillance activities: NIOSH-funded research grants. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/programs/surv/grants.html (accessed November 29, 2017).

NIOSH. 2015. National Health Interview Survey: Occupational Health Supplement. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/nhis/summary.html (accessed June 19, 2017).

NIOSH. 2016. About NIOSH. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/about (accessed January 22, 2017).

NIOSH. 2017. Coal workers’ health surveillance program. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/cwhsp/ (accessed June 4, 2017).

NRC (National Research Council). 1987. Counting Illnesses and Injuries in the Workplace: Proposals for a Better System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

OMB (Office of Management and Budget). 2007. Implementation Guidance for Title V of the E-Government Act, Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act of 2002 (CIPSEA). Notice of Decision. 72 Federal Register 33362-33377.

OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration). 2012. Injury and illness prevention programs white paper. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/dsg/topics/safetyhealth/OSHAwhite-paper-january2012sm.pdf (accessed March 25, 2017).

OSHA. 2014. Medical screening and surveillance requirements in OSHA standards: A guide. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3162.pdf (accessed March 13, 2017).

OSHA. 2016a. Clarification of employer’s continuing obligation to make and maintain an accurate record of each recordable injury. Final rule. 81 Federal Register 91792-91810.

OSHA. 2016b. Recommended Practices for Safety and Health Programs. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/shpguidelines/docs/OSHA_SHP_Recommended_Practices.pdf (accessed March 25, 2017).

OSHA. 2017a. About OSHA. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/about.html (accessed January 22, 2017).

OSHA. 2017b. State plans. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/dcsp/osp/ (accessed January 27, 2017).

OSHA. 2017c. Report a fatality or severe injury. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/report.html (accessed January 22, 2017).

OSHA. 2017d. Establishment specific injury & illness data (OSHA Data Initiative). Available online at https://www.osha.gov/pls/odi/establishment_search.html (accessed January 23, 2017).

OSHA. 2017e. Non-mandatory appendix A to subpart B — Partially exempt industries. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/recordkeeping/ppt1/RK1exempttable.html (accessed August 21, 2017).

OSHA. 2017f. Final rule issued to improve tracking of workplace injuries and illnesses. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/recordkeeping/finalrule/index.html (accessed January 23, 2017).

OSHA. 2017g. Chemical exposure health data. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/opengov/healthsamples.html (accessed March 25, 2017).

OSHA. 2017h. Safety and health program voluntary standards. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/shpcampaign/voluntary-standards.html (accessed March 25, 2017).

OSHA. 2017i. OSHA Injury and illness recordkeeping and reporting requirements. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/recordkeeping/index.html (accessed December 20, 2017).

Reason, J. T. 1997. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Reeve, G. R. 2016. Occupational health surveillance in manufacturing. Presentation to the National Academies Committee on Developing a Smarter National Surveillance System for Occupational Safety and Health in the 21st Century, September 21. Available online at https://vimeo.com/187718132 (accessed July 10, 2017).

Schnorr, T. 2016. NIOSH surveillance program: Overview. Presentation to the National Academies Committee on Developing a Smarter National Surveillance System for Occupational Safety and Health in the 21st Century, June 15. Available online at https://vimeo.com/172464267 (accessed July 10, 2017).

Sengupta, I., and M. L. Baldwin. 2015. Workers’ Compensation: Benefits, Coverage, and Costs, 2013. Washington, DC: National Academy of Social Insurance. Available online at https://www.nasi.org/research/2015/report-workers-compensation-benefits-coverage-costs-2013 (accessed March 25, 2017).

Stanbury, M. J., H. Anderson, P. Rogers, D. Bonauto, L. Davis, B. Materna, and K. D. Rosenman. 2008. Guidelines for Minimum and Comprehensive State-based Public Health Activities in Occupational Safety and Health 2008. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2008-148. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2008-148/pdfs/2008-148.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

Thomsen, C., J. McClain, K. Rosenman, and L. Davis. 2007. Indicators for occupational health surveillance. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 56(RR-1):1-7.

WA DLI (Washington State Department of Labor and Industries). 2013. ESSB 5744: Report on the Development and Implementation of the Logger Safety Initiative—2013 Report to the Legislature. Available online at http://www.lni.wa.gov/Main/LoggerSafety/pdfs/LoggerSafetyInitiative.pdf (accessed June 19, 2017).