2

Setting the Stage

Georges Benjamin’s introductory remarks and Jonathan Patz’s opening presentation set the stage for the remainder of the workshop. This chapter summarizes Benjamin’s remarks and Patz’s presentations, with key points listed in Box 2-1.

Following his presentation, Patz participated in an open discussion with the audience. A wide range of topics were addressed, including how health professionals and urban planners can work together; implications of geographic variation in indoor versus outdoor air pollution; tree canopy spread as a mitigation strategy; the return on investing in green energy; populations that are particularly vulnerable to the health effects of climate change (children, elderly, the poor); the emerging issue of environmental refugees; engaging leaders at the national and global levels; how to talk about climate change; and political organizing and partnerships. This discussion is summarized at the end of this chapter.

THE FIERCE URGENCY OF NOW

We are now faced with the fact that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history there is such a thing as being too late. Procrastination is still the thief of time. . . . We must move past indecision to action.

Martin Luther King, Jr.1

___________________

1 Quote from the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s April 4, 1967, speech, Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence, delivered at “a meeting of Clergy and Laity Concerned About

Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association (APHA), reminded the audience that just 2 weeks prior to this workshop, people were walking around Washington, DC, without coats, some in shorts, in contrast to the large snow storm forecast for the day after the workshop. “No one is going to tell you for sure that that’s related to climate change,” Benjamin said, but he encouraged workshop participants to keep in mind, over the course of the day, that such huge climate shifts and environmental changes are being observed right now, with many records being broken.

“Climate change is the most pressing public health problem that we have,” Benjamin said. He cited several reasons why the health sector should be engaged. First is the global nature of the threat. “From a global perspective, it’s huge,” he said. Second, climate change affects every facet of our lives. Third, it represents an excellent opportunity to solve a problem using a public health approach, particularly a health-in-all policies approach. He emphasized the enormous opportunities for people from multiple sectors to work collaboratively on a problem that extends across a range of hu-

___________________

Vietnman at Riverside Church in New York City.” See http://inside.sfuhs.org/dept/history/US_History_reader/Chapter14/MLKriverside.htm (accessed May 11, 2017).

man activities, from what we eat and how we grow our food to how we build our environment, how we live our daily lives, and what we burn for fuel. “Taking the politics out of this, simply to make sure that our planet and those of us that are on our planet actually survive, is an excellent opportunity,” he stated.

APHA has been thinking about the impact of climate change on health since the early 1990s, according to Benjamin. He noted that several years ago, the APHA executive board declared “becoming the healthiest nation” a central challenge and that dealing with climate change aligns with this challenge.

Climate change also presents an enormous opportunity, Benjamin continued. “Certainly we know,” he said, “climate change is here and impacting our health today.” But some important policy makers do not support climate change, and some do not even believe it is real. This lack of support and disbelief create urgency, making climate change, Benjamin said, “an issue we must take on now.” In his opinion, this urgency, in turn, creates an opportunity to “set the table from a health perspective” and for the health community to fill what he described as an “enormous void.” Finally, Benjamin asserted, not only is action needed now, but timely action will also keep the issue in the forefront of the minds of the public, policy makers, and funders. He suggested four health-sector goals:

- Shift the narrative around climate change to speak to people’s values regarding their health and that of their families and loved ones. “People love polar bears,” he said, “but they love their health and their family’s health more.”

- Serve as a science and policy resource to inform sound policies and decision making and to evaluate the health equity impacts of those policies.

- Influence and advance climate policies that would have the greatest impact on environmental justice and health equity outcomes.

- Galvanize action to advance climate-healthy practices and behaviors that will make the greatest impact on public health and health equity.

The Year of Climate Change and Health

APHA declared 2017 the year of “Climate Change and Health,” a declaration, Benjamin explained, with two goals. One is to raise awareness by educating people that climate change is a public health issue and not just an environmental issue. The second is to mobilize leaders who are interested in climate change, but have not started to take action yet.

The association is striving to meet these goals by proactively planning

events, as well as adopting events, such as this Health and Medicine Division (HMD) workshop, that are aligned with the goals of 2017 as the Year of Climate Change and Health. Each month of 2017, in collaboration with its partners, APHA has been or will be focusing on a specific theme to raise visibility and build momentum. The year would conclude with the APHA Annual Meeting (theme: Climate Changes Health) in Atlanta.

In addition to this HMD workshop, another recent event adopted by APHA because of its alignment with APHA’s work in climate change was the Climate & Health Meeting held in Atlanta on February 16, 2017. That meeting was held to fill the void of the deferred Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Climate & Health Summit, Benjamin explained. He thanked former Vice President Al Gore for co-hosting the meeting, as part of Gore’s Climate Reality Project, and acknowledged the other co-hosts as well: Harvard Global Health Institute, University of Wisconsin Global Health Institute, and University of Washington Center for Health & the Global Environment. In addition to these co-hosts, the meeting drew more than 50 partners. The meeting was funded by the Turner Foundation and held at the Carter Center. In fact, Benjamin noted, former President Jimmy Carter attended the meeting and greeted participants. The meeting drew about 340 local participants and thousands of remote participants. At one point, according to Benjamin, the meeting trended at #2 on Twitter, an indication, he said, that “a lot of people are interested in this.”

Questions from the Audience: Shifting the Narrative and Response Versus Mitigation

Following his remarks, Benjamin fielded two questions from workshop participants. First, George Isham asked Benjamin to expand a bit on the first of the four suggested health-sector goals that he listed, that is, to shift the narrative around climate change to speak to people’s values around their health. Benjamin replied that the challenge is that people tend to think about what they are going to lose from climate change adoption, for example, by reducing use of fossil fuels. Instead, he said, “We ought to be talking more about what we gain, particularly from a population perspective.” By acting now, he explained, people can make the environment cleaner and build jobs, ultimately at a reduced cost to society and for improved overall well-being. Even at an individual level, taking action now will make a difference, in his opinion. Based on his work as a former emergency physician, he foresees fewer people walking into emergency rooms with asthma attacks, fewer seniors being impacted by heat-related injuries, and less worry about flooding and vector-borne diseases associated with that flooding. He remarked that there have been yearly vector-borne infectious disease emergencies over the past several years and that the environment is changing in

such a way that makes it more receptive to these diseases. “We can stop that,” he said. “It may take years, but we can change it.”

Benjamin was then asked by an unidentified member of the audience how the public health community is talking with decision makers about the need to respond to immediate, “every day” health impacts versus impacts that are anticipated in the future. Benjamin stressed the importance of taking care of the emergency “in front of us.” He referred, again, to the snow storm expected to hit Washington, DC, on the day after this meeting, and stressed the importance of having a system in place that can respond to the coming storm. In his opinion, this means having a well-structured, well-funded emergency response system that can deal not only with situations such as snow removal, but also with seniors who will lose their heat and with other individuals who are at risk of being affected by severe weather.

That this same response capacity also helps with mitigation is important, he continued, because the core governmental public health system has been devastated over the past several years. For example, despite the possibility that Zika could return in the spring, at least in the south, mosquito control programs have languished. Now is the time to begin building those programs, he said. Benjamin cautioned that gutting the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations will put people at “extraordinary risk.” These regulations were put in place because there were problems that needed to be fixed. “We’re trying to get the average American to understand that,” he said, so people can say to the resource allocators, “We need to have these systems, these programs, these regulations in place.”

THE GLOBAL CLIMATE CRISIS: LARGE HEALTH RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES2

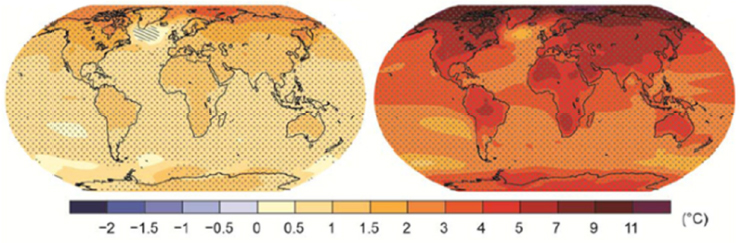

Jonathan Patz’s presentation set the stage for the remainder of the workshop, beginning with a description of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s future projections for average surface temperatures across the globe (IPCC, 2013). Patz compared 1986–2005, a period of time he described as a “low emissions scenario,” which resulted in a 1 degree (°C) warming by the end of the century (on average, worldwide), with 2081–2100, a period of time when, if “business as usual right now” proceeds, will see a warming of 7–8°C (again, on average across the world) (see Figure 2-1). He asked, “Now, what does this mean for health?” He answered, “This is why we’re here—the so what?” He reiterated Benjamin’s key point that climate change is not only a major health risk, but also actions against climate change represent a huge opportunity for health.

___________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Jonathan Patz, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

SOURCES: Patz presentation, March 13, 2017, adapted from Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis; IPCC, 2013.

Health Effects of Climate Change

Patz emphasized that climate change involves not only temperature rise and sea level rise, but also hydrologic extremes (i.e., more droughts and more flooding, major blizzards and snowstorms). As Benjamin also noted, Patz referred to the record number of consecutive hot days in Washington, DC, in February 2017, followed by a blizzard expected the day following this workshop. These changes, he said, “cut across all sorts of health outcomes that we know are climate sensitive.”

Such outcomes include heat stress and cardiovascular failure associated with heat waves; air pollution and aeroallergens (i.e., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and other respiratory diseases); infectious diseases, particularly vector-borne diseases (e.g., malaria, dengue, encephalitis, hantavirus, Rift Valley fever); water-borne diseases (e.g., cholera, cyclospora, cryptosporidiosis, campylobacter, leptospirosis); water resources and food supply problems (e.g., malnutrition, diarrhea, toxic red tides); and mental health outcomes and environmental refugees (i.e., forced migration, overcrowding, infectious diseases, human conflicts) (Patz et al., 2000). Patz cautioned that it is very difficult to attribute environmental refugees to climatic events, but suggested that a drought or sea-level rise that forces population movement could be the “iceberg under the tip of the iceberg as far as the extent of impact.”

In addition to these listed highly climate-sensitive health outcomes, he noted that new findings emerge “every day.” For example, recent studies out of Southeast Asia show increases in hypertension and preeclampsia associated with sea-level rise and salinization of freshwater aquifers.

Patz went on to discuss some of these health outcomes in more detail,

beginning with outcomes associated with extreme heat events in New York City (NYC).

Temperature Rise: Examples of Health Impact

Currently, NYC experiences, on average, 13 summer days that are 90°F or hotter. It is predicted that this number will triple, from 13 to 39 days, by 2046–65 (Patz et al., 2014). This predicted tripling, Patz noted, holds for all of the eastern cities he and his colleagues have examined thus far. “This is a major concern,” he said. “We know that people die in heat waves.”

Not only do people die in heat waves, but crops become damaged. It has been predicted that many places worldwide will experience unprecedented summer heat in the future, with many regions experiencing a 90 percent or greater probability of having the hottest summer on record by 2080–2100 (Battisi and Naylor, 2009). Patz remarked that, based on this prediction, today’s 840 million people at risk of hunger could double by mid-century.

While crops are damaged by rising temperatures, some plants may actually thrive in warmer temperatures and with higher CO2 levels. This is “bad news,” Patz said. He explained how work conducted by Lewis Ziska, U.S. Department of Agriculture, has shown that ragweed pollen season has been increasing over the past few decades and, therefore, children with asthma are at risk for a longer period of time (Ziska et al., 2016).

Regarding Zika virus, which Benjamin had noted, Patz mentioned that a new study shows that the risk for transmission of Zika was higher in 2015–2016 than it has been in more than 60 years, based on climate suitability of the Aedes aegypti mosquito (Caminade et al., 2016). This is not surprising, in Patz’s opinion, based on what is known about dengue fever—the two viruses are very similar, with the same mosquito vector. In Southeast Asia, where dengue fever occurs every year and with an expected seasonal peak, the couple of years that have experienced major epidemics have coincided with very strong El Niño weather events (i.e., 1997 and 2009) (van Panhuis et al., 2015). The 1997 El Niño was the strongest in recent history, Patz noted, until 2015. Based on what he and colleagues have observed with respect to surface temperatures in South America associated with the 2015 El Niño, Patz suspects that it had at least something to do with the recent emergence of Zika in South America.

Hydrological Extremes: Examples of Health Impact

Patz reiterated that climate change encompasses more than global warming—it also includes extremes in the hydrological cycle. According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program, Patz said, “In the future,

when it rains, it will pour,” because hot air holds more moisture. These rains affect public health through water contamination. A hard rain, combined with a system that is unable to handle the storm water, can lead to combined sewage overflow events. In an analysis of future precipitation intensity in Chicago, Patz and colleagues predicted a doubling of combined sewage overflow events by 2050 because of the increased rainfall and runoff (Patz et al., 2008).

In Syria, in contrast, decreasing rainfall, coupled with an increasing temperature, has led to extreme drought. Patz explained that before the civil war, which led to hundreds of thousands dead and millions of refugees, Syria experienced the most severe drought in the instrumental record (Kelly et al., 2015). While the impact of the drought on the refugee population is hard to pinpoint, to the extent that migration from rural to urban locations was three to four times its normal level, coupled with food prices being “through the roof,” all in the midst of civil unrest, the drought could have had indirect, destabilizing, and enormous effects. According to Patz, potential effects like these are one reason why President Obama began talking about climate change as a national security issue.

Changing the Framing of Climate Change

In addition to President Obama’s reframing of climate change as a national security issue, there have been efforts to reframe climate change in other ways as well, Patz continued. He referred to Benjamin’s remarks on the present opportunity to reframe climate change as a health issue, and not just an environmental issue.

Climate change has also been framed as a moral issue (i.e., the “Pope Francis effect”). Ten years ago, Patz and colleagues (2007) published a cartogram (a map combining statistical and geographic data) showing which countries were producing the most CO2, with the United States as the top emitter. Since then, Patz noted, China has surpassed the United States in CO2 emissions. Yet, for the most climate-sensitive diseases (i.e., malaria, malnutrition, diarrheal disease), the greatest initial impact is in sub-Saharan Africa and India. The fact that Americans are emitting six times the global average CO2 per capita compared to what the rest of the world creates, Patz said, “a big ethical dilemma.”

He told the workshop audience how he had the good fortune to show this same cartogram to His Holiness the Dalai Lama at an event in 2011, and the Dalai Lama responded, “If you know pollution kills, your country is not showing much compassion, correct?” When Patz told the Dalai Lama that there was no knowledge about pollution until the 1952 killer London smog event, and little knowledge about climate change until the 1990s, His Holiness responded, “Well, it’s 20 years later, and you’re still

cranking away, polluting and killing people around the world with your energy policies.”

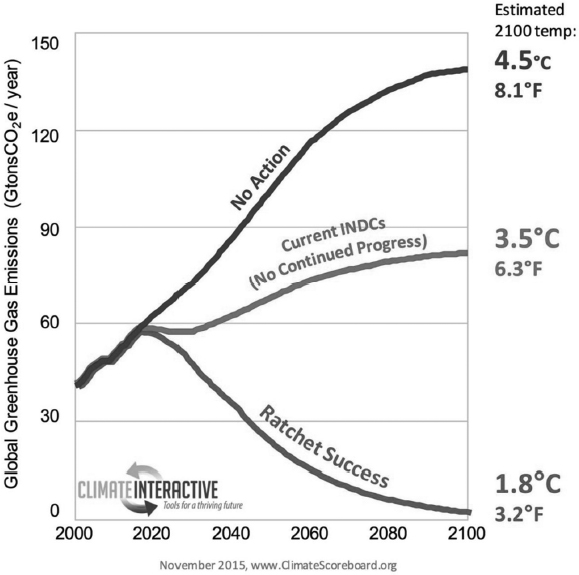

Today, Patz said, “we are in a new era of awareness,” one marked by the Framework Convention on Climate Change, which was held in Paris in 2015. He considered the conference a turning point, with a record number of heads of state (143) and 183 countries committing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The United States committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 28 percent by 2030; the European Union committed to 40 percent. “These are big commitments,” Patz said. However, even with these commitments, the global average surface temperature of the earth is still likely to rise by 3.5°C by 2100 (compared to 4.5°C with no action), Patz explained (see Figure 2-2). Scientists have been warning that it will be necessary to stay below a 2°C warming to avoid catastrophic problems and ecosystem collapse. To decrease global warming to below 2°C, he said, immediate and substantial action is needed.

Cost-Free Climate Change Policy: Opportunities for Health

The way to achieve these immediate and substantial actions, Patz argued, is to not only frame climate change as a public health concern, but also to make the case that policy to combat climate change could be cost neutral. Moreover, with the many public health benefits from climate change policy, especially with respect to non-communicable chronic diseases such as heart disease and cancer, climate change policy could even create a net gain.

Patz identified three sectors where he sees opportunities for a health-in-all-policies approach to combat climate change: (1) the energy sector, (2) food systems (food and agriculture), and (3) transportation and urban planning. He discussed each sector in turn.

The Energy Sector

With respect to potential public health-related policy changes in the energy sector, Patz referred to the World Health Organization estimates of more than 3 million people dying prematurely every year from outdoor air pollution, mostly from urban exposures, and more than 4 million people dying prematurely every year from indoor air pollution, largely from inefficient cookstoves that use biomass (e.g., firewood) and coal. He explained that burning fossil fuels leads not only to the emission of greenhouse gases, but also to the emission of pollutants. In a study on the health co-benefits of a cleaner energy system in the United States, Thompson et al. (2014) predicted that such a system would reduce both ozone and particulate matter (PM2.5), with health benefits offsetting the health system’s upfront

NOTE: Predicted change in the global average surface temperature of the earth with no action taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (top), action based on current Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) (middle), and more immediate and substantial actions than have been promised (bottom).

SOURCES: Patz presentation, March 13, 2017; reprinted with permission from Climate Interactive. Visit https://www.climateinteractive.org/programs/scoreboard (accessed August 1, 2017) for updated figure.

investment by 26 to 1,050 percent. In other words, Patz explained, the health benefits could be up to 10 times greater than the economic cost of investments in green technology.

Policy makers need to understand these health co-benefits of green technology, Patz urged. While it may take more than $30 to remove one ton of CO2 from the atmosphere by investing in, for example, solar or wind technology, that is only half the equation. Removal of a ton of CO2 from the atmosphere also removes a lot of PM2.5 and other pollutants such that the health benefits could average $200 for every ton of CO2 removed (West

et al., 2013). Thus, there are huge gains to be made by investing in cleaner energy, particularly in highly polluted countries. In East Asia, for example, the benefit could be much greater than $200 per ton, Patz suggested. Moreover, the cost of cleaner energy will likely decrease in the future. Over the past 40 years, solar energy has dropped in price by 99 percent.

“China gets this,” Patz said, referring not only to the Chinese president’s support for the Paris Agreement, but also the fact that China is the number one producer of solar panels. Additionally, while China does have a coal-fired power plant problem, it recently decided not to move forward with plans for another 80–90 coal-fired power plants, according to Patz, who added, “[e]ven if the United States backs out, China is going to be moving forward.”3

Food Systems

The food and agriculture sector is another area where environmental policies can have significant health co-benefits. Patz showed a photograph from the 2014 People’s Climate March in NYC, with a sign on a large inflatable cow stating, “I am full of greenhouse gas. Do you have a ‘steak’ in it?” He remarked that many people recognize that eating lower on the food chain is better for both the environment and our health. In a comparison of high meat, low meat, fish, vegetarian, and vegan dieters in the United Kingdom, Scarborough et al. (2014) found that a high meat diet had the highest mean dietary greenhouse gas emissions (i.e., in kilograms of CO2 equivalents per day, so the amount of energy required to produce one kilogram of protein), followed by a fish diet, then the vegetarian diet, then vegan diet. In another UK study, Westhoek (2014) reported that not only would reducing meat consumption by half cut greenhouse gas emissions by 25 to 40 percent, but it would also reduce saturated fat in the diet by 40 percent, thereby increasing cardiovascular health.

Transportation and Urban Planning

In a 2016 study published in The Lancet, NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RIsC, 2016) members reported on the increasing numbers of obese and severely obese people around the world by region. Patz asserted that while this unfortunate global trend that affects both men and women is partly food related, it is also related to how cities are designed. Pucher et al. (2010) reported that U.S. cities with the highest rates of walking and cycling to work have 20 percent lower obesity rates and 23 percent lower

___________________

3 On June 1, 2017, President Donald J. Trump announced that the United States would withdraw from the Paris climate accord.

diabetes rates, compared to U.S. cities with the lowest rates of walking and cycling. “It is high time that we design cities for people, rather than for motorized vehicles,” Patz said.

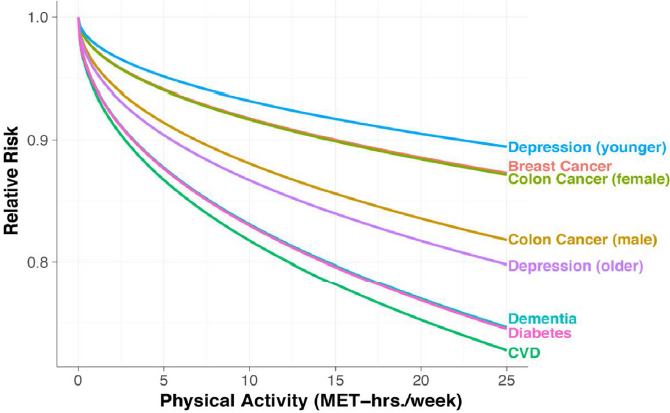

Patz quoted acting Surgeon General Boris Lushniak, who said at the 2014 Climate Summit, “America does not have a health care system. We have a ‘sick-care’ system. A health care system extends far beyond medical centers and includes safe routes to school, clean air and water, and flourishing healthy communities.” He then cited several epidemiological studies showing that designing communities to promote physical fitness could have huge health gains, including reductions in cardiovascular disease (Hamer and Chida, 2008), diabetes (Jeon et al., 2007), dementia (Hamer and Chida, 2009), depression (Woodcock et al., 2009), colon cancer (Harris et al., 2009), and breast cancer (Monninkhof et al., 2007) (see Figure 2-3). In addition, Patz described how he and colleagues are currently modeling the health effects of an increase in mean walking time, with preliminary data suggesting that increasing people’s walking time by just 10 minutes per week, or 2 minutes per work day, would save the state of Wisconsin $30 million in health care and absenteeism costs.

Regarding the current administration’s discussion of a trillion-dollar investment in infrastructure, Patz said, “What a golden opportunity for public health,” adding that infrastructure is not just highways and bridges, but also bike trails and green communities.

Pivot to Local Leadership

Patz commented that the new administration’s views on climate change are different from those of the previous administration. “We really need to start thinking about pivoting the local leadership,” he urged. Opportunities for local leadership extend across state public health departments, the health care system, and nongovernmental organizations. Patz also mentioned the C40 city leaders,4 who have insisted that they “will not be slowed down” if the new administration does not support climate change policy: CDC’s Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) program (the summary of Paul Biedrzycki’s presentation in Chapter 4 includes a discussion of New Hampshire’s use of the BRACE framework); Health Care Without Harm (an organization working to transform health care for environmental health and justice); Kaiser Permanente’s multifaceted sustainability efforts (see the summary of Kathy Gerwig’s presentation in Chapter 6); the pioneering work by Gundersen Health System to invest in renewable energy in La Crosse, Wisconsin (see the summary of Jeff Thompson’s presentation

___________________

4 C40 is a network of megacities around the world committed to addressing climate change.

NOTES: The relationship between physical activity and relative risk for several health outcomes, based on epidemiological studies. CVD = cardiovascular disease; MET = metabolic equivalent.

SOURCES: Patz presentation, March 13, 2017, developed from the following references: Hamer and Chida, 2008, 2009; Harris et al., 2009; Jeon et al., 2007; Monninkhof et al., 2007; Woodcock et al., 2009; reprinted with permission from Patz.

in Chapter 4); the Climate and Health Alliance; and the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health.

In conclusion, Patz emphasized that addressing the global climate crisis through a low-carbon economy, especially across the energy sector, with the food system, and in transportation and urban planning, can help make people healthier and save money. “Doing something urgently about the global climate crisis,” he said, “could be the largest public health opportunity we’ve had in a very long time.”

DISCUSSION

Following his presentation, Patz answered questions from the audience touching on multiple themes.

Health Professionals and Urban Planners

An audience member, Kelly Dennings, asked whether the public health community is reaching out to urban planners and how this relationship is being fostered. Patz replied that when health professionals show up at urban planning meetings, they are welcomed with open arms. Urban planners appreciate the input. He urged more engagement on the part of the health profession, particularly given that there is receptivity at the other end. As an example, he mentioned the Sustainable City Year Program, which partners universities with cities for service-based learning, and some of these partnerships involve health impact assessments. In fact, one of Patz’s classes is currently (at the time of this workshop) conducting a health impact assessment for a nearby city as part of this program. Additionally, he mentioned that the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has prioritized projects on exercise and livable communities.

Infrastructure Policy: Adaptation and Mitigation

Lynn Goldman mentioned having co-authored a National Academy of Medicine Perspectives paper, Advancing the Health of Communities and Populations: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care (Goldman et al., 2016), which addresses infrastructure and health-in-all-policies around infrastructure. She commented on the need to consider both how to train people going into public health and how to create opportunities for communities to engage public health in decision making around infrastructure. In addition, Goldman remarked that Patz had mentioned walkability and bikeability, but there are many other components of infrastructure as well. For example, too often, when roads are addressed, no one pays attention to the things that run under those roads, namely, drinking water and liquid waste. Referring to a recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report attributing many severe weather events to climate change (NASEM, 2016), Goldman pointed out that infrastructure also encompasses aspects that are important for protection from severe weather events. She asked Patz to reflect on steps that need to be taken to prepare communities for these events, while at the same time making communities more aware that steps also need to be taken “on the longer haul” to prevent such events from becoming even more serious and more frequent. She observed that science is increasingly attributing many severe weather events to climate change, yet, she said, “We’re still very cautious, I think, as a community about being clear to the public about that.”

Patz replied, “We should not be thinking either/or,” meaning either adapt or mitigate. In his view, communities need to take a two-pronged

approach. They need to be ready for what is already happening. He agreed with Goldman that there is a complexity to adaptation, for example, with respect to roads being built for walking, biking, and motorized vehicle safety. He called attention to the ecological aspects of infrastructure as well. For example, building a sea wall to hold the ocean back as an adaptation to sea level rise can kill an estuary or mangrove, thereby destroying fisheries in the region. “So when you think about adaptation, first, do no harm,” he said. But then, think more broadly about potentially damaging unintended consequences. He called for a more interdisciplinary adaptation approach and greater engagement across disciplines. In addition to being prepared, at the same time, he said, “We also need to go upstream and be mitigating the root problem to reduce fossil fuel emissions.”

Air Pollution

Phyllis Meadows of the Kresge Foundation asked Patz whether the fact that indoor air quality is contributing to more deaths worldwide compared with outdoor air quality threatens “the narrative” and whether indoor and outdoor air quality issues should be discussed in tandem to engage a broader audience. Patz replied that, depending on where in the world you live, the intervention and health benefit will be different. In poor countries where people cook with coal and wood and where there is a lot of PM2.5 exposure indoors, using cleaner cooking fuels is important. In these areas, especially in East Asia, indoor air pollution is an enormous problem. But in the United States, for example, there is more to gain by addressing outdoor air pollution.

Tree Canopy Spread as a Mitigation Strategy

Terry Allan from the Cuyahoga County Board of Health, Ohio, remarked that there has been a lot of recent talk in urban planning around tree canopy spread as a mitigation strategy. He asked Patz to comment on the importance of and opportunities for tree canopy spread from a public health perspective. Patz replied that, given that most people live in an urban environment, it is extremely important to be smart about prevention in this environment. During his talk he had mentioned the role of walkability and bikeability in increased exercise. The greening of cities, he said, not just through trees, but also, for example, by growing green rooftops, plays a very important role in reversing the urban heat island effect seen in built-up areas that experience higher temperatures than surrounding rural or less developed areas due to pavement and roofs that limit vegetation and

moisture.5 He added that trees also reduce rainfall runoff and contamination. Finally, he mentioned the mental health benefits of a green canopy and a Wisconsin study showing that the extent of green cover canopy in an urban environment has as much of an effect on mental health as moving or divorce. One caveat about trees, he noted, is that some trees emit more volatile organic compounds, which are a precursor to ozone smog pollution, and others also give off more pollen, underscoring the importance of carefully selecting tree species to plant in cities.

Returns on Investing in Green Energy

“The return on investment data that you show is almost shocking,” David Kindig of the University of Wisconsin remarked. He wondered whether any work being done with social impact bonds6 has shown similar returns, adding that he was unaware of a similar level of return for bonds in the areas of early childhood or criminal justice. Patz replied, “It’s no surprise, really, the $30 versus $200.” He recalled that when EPA’s Clean Air Act required benefit-cost assessments, it was discovered that every $1 investment in clean air returns $30 or more. These numbers, in his opinion, are critical, especially with the new administration beginning to roll back regulations. He urged a greater understanding of the value of these regulations. He noted that EPA has announced an assessment of climate change policies and suspected that such an assessment will likely examine only the energy cost side of the equation (i.e., the $30 investment), without considering the health benefit side (i.e., the $200 benefit). This is impetus, in his opinion, to “get the public health issue on the table.”

Kindig also mentioned the Internal Revenue Service community benefit requirement for nonprofit hospitals and recent discussions about moving that benefit in a direction more explicitly oriented toward improving population health. He asked if Patz had seen this type of investment as an important part of any nonprofit hospital portfolio. Patz mentioned Jeff Thompson’s work with the Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wisconsin, where they are reinvesting into the community and seeing great gains in health promotion and disease prevention (Thompson’s presentation is summarized in Chapter 4).

___________________

5 The Environmental Protection Agency provides information about urban heat islands on its website; see https://www.epa.gov/heat-islands/learn-about-heat-islands (accessed May 9, 2017).

6 Social impact bonds, also known as pay for success financing, “allow philanthropic funders and private investors to pool capital for social programs, with the loans repaid by the government only if the funded initiative achieves agreed-on results” (IOM, 2015, p. 35).

Vulnerable Populations: Children, Elderly, and the Poor

Debbie Chang of Nemours asked Patz if children have been included in any of the return on investment studies and if there have been any targeted approaches for addressing health equity issues. Patz replied that, according to the World Health Organization, 88 percent of climate change impacts affect children. Diarrheal disease, malnutrition, and malaria, for example, are all very climate sensitive and strongly affect children. In the United States, children are particularly vulnerable to allergens (i.e., asthma). Older adults are also vulnerable, particularly with respect to heat waves. Finally, Patz reminded the workshop audience that it was people who could not afford to leave town that suffered the most from Hurricane Katrina.

Environmental Refugees

Sanne Magnan of the University of Minnesota asked Patz to speak more to the issue of environmental refugees. Patz replied that the fact that the Syrian Civil War was preceded by the worst drought in instrumental record makes it very difficult to tease out the impact of climate change. The extreme environmental conditions of climate change—not just drought, but also sea-level rise—push people around a lot, he said. That destabilization alone, with people being forced to move and resettle and either having no immunity to new diseases or bringing diseases with them, creates a huge public health burden. He urged that, even though it is difficult to quantify the effect on refugees, this destabilization is something to keep in mind.

Maureen Lichtveld of Emory University added that there are environmental refugees in the United States as well. She referred to the communities facing displacement due to the retreat of the bayous and loss of land on the Gulf Coast.

Engaging Leaders at the National and Global Levels

Benjamin Miller, an audience member from RAND Corporation, agreed with Patz’s suggestion to engage local leaders, but said, “This is also a national and global issue.” He asked Patz how to engage those leaders while also engaging local leaders. Acknowledging that there will always be uncertainty, Patz replied, “We absolutely need to be better at communicating the truths that we know, or at least the best of science that we know.” He expressed discouragement that the head of EPA does not think there is a relationship between CO2 and climate when, in fact, a great deal is known about that relationship. He mentioned a study showing that 97 percent of climate scientists agree that not only is global warming occurring, but the warming is attributed to human activity, mostly the burning of fossil fuels

(Cook et al., 2016). He urged keeping in the public ear the fact that a huge majority of climate scientists agree that climate change is real. “Pivot to local leadership,” he said, “but also keep informing the general public.”

How to Talk About Climate Change

Magnan reflected on the skepticism that many policy makers and the general public have toward climate change. She asked Patz, based on his work, what perspectives or stories most resonate with people who are skeptical.

The most important messages to communicate, Patz replied, are “Climate change is real. It’s now. It’s already happening. It’s solvable.” Patz clarified that there is no scientific debate about whether climate change is happening, other than a few outliers. The debate, he said, is political. Moreover, it is actionable. He mentioned again that the price of solar energy has dropped. Wind energy has also become competitive. These technologies are not things that we have to wait for; they already exist. “We can do something right now,” he said.

In addition to these messages, he suggested not using the term “climate change” when talking to people who do not believe in climate change. Talk instead about extremes in climate variability, water stress, or heat waves. Instead of talking about interventions to mitigate climate change, talk about reducing fossil fuel combustion and the immediate health benefits of doing so (i.e., better food quality, exercise promotion, cleaner air quality).

George Isham reflected on the fact that people without a science background may not be able to evaluate highly technical or scientific descriptions. He suggested that one strategy for improving public understanding is to identify the top 10 things to know in order to understand an issue or topic beyond the political [debate] level. In response, Patz said the first thing even experts need to do is to become expert listeners. “Our engagement has to be much more participatory,” he said.

Lichtveld added that, in her opinion, perhaps the highest priority message coming out of this workshop is to increase environmental health literacy. “Whether it is here, whether it’s in New Orleans, or across the world,” she said, “it is that, that will empower us.”

Political Organizing and Partnerships

Patz was asked by an unidentified audience member to expand on ways to communicate science-based evidence in light of the reality that the current federal administration may not be influenced by such evidence. The audience member expressed dislike of the phrase “postfact era,” but admit-

ted “that seems to be what we are in.” The audience member asked how the federal policy space could be more assertively entered and suggested that perhaps partners, some unusual allies, may play a role. He asked, “Where are the edges? Where are the barriers?”

Patz agreed that finding good partners and coalitions is absolutely necessary. Although scientists need to be better communicators, he agreed that they are not necessarily going to convince people. He mentioned the Climate and Health Alliance, which was represented at this workshop by Linda Rudolph (Rudolph moderated the Session 1 panel discussion, summarized in Chapter 2), and said the most trusted professionals in the United States are nurses (the Climate and Health Alliance represents health care professionals from a range of disciplines, including nurses). “Finding these new coalitions is extremely important,” he said.

Additionally, Patz urged visibly engaging with and investing in disadvantaged populations, coal miners in particular. He stressed the importance of job diversification. Otherwise, as we shift away from coal, coal miners will be left behind. He said, “We need to be out there taking care of them and being very proactive about that.”

This page intentionally left blank.