3

Regional Perspectives from the South

Moderated by Linda Rudolph, Panel 1 speakers addressed a range of city and state-wide climate change health scenarios and strategies being implemented and developed in the South, specifically in Kentucky.

Maria Koetter opened the panel with a presentation on findings from two recent city-wide urban heat and tree buffering analyses and steps being taken by the city of Louisville to address climate change and its impact on health.

In the question and answer period at the end of the panel, she emphasized the important role of strong city leadership and an awareness among city leaders, including the mayor, regarding the issues. Next, Halida Hatic and Rachel Holmes provided a joint presentation on a Louisville project, Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces, that serves as a tool for religious organizations to conduct tree canopy assessments and evaluate other components of their landscape and their relationship with that landscape. The fourth and final panelist, Lisa Abbott, described Kentuckians for the Commonwealth’s (KFTC’s) work to develop a grassroots People’s Plan for the state’s energy future. This chapter summarizes these presentations. Key points made by each panelist are listed in Box 3-1.

The open discussion with the audience at the end of the panel covered a range of issues: the role of the health sector in local efforts to address climate change; building political will; engaging the private sector; engaging religious networks; and the concept of “just transition” (i.e., from traditional energy, namely coal). This discussion is summarized at the end of this chapter.

LOUISVILLE METRO GOVERNMENT OFFICE OF SUSTAINABILITY1

Maria Koetter opened the panel by sharing work under way in Louisville’s Office of Sustainability. Currently, the office is working through a comprehensive sustainability plan, with a focus on energy efficiency, green infrastructure (i.e., tree canopy, reforestation), and urban heat management.

Urban Heat Analysis: Findings from Louisville

In 2012, Brian Stone, Georgia Institute of Technology, released a study showing that Louisville had the most rapidly growing heat island in the country from 1961 to 2010. This finding, Koetter said, raised a red flag,

___________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Maria Koetter, LEED AP, Director of Sustainability, Office of Sustainability, Louisville Metro Government, Kentucky.

prompting an application for a grant from Partners for Places. The grant was awarded, allowing the city to hire Stone to conduct an in-depth analysis of Louisville’s urban heat island issues and to model strategies to help manage the heat. His analysis also included population vulnerability and heat mortality findings.

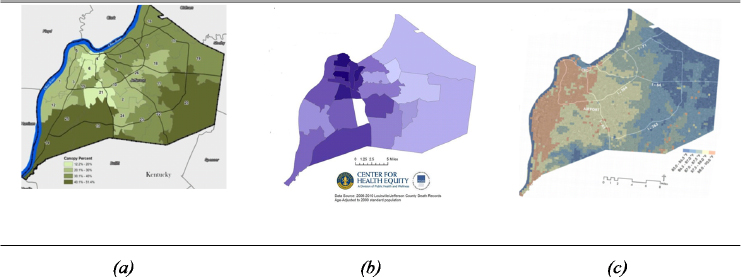

In addition to Stone’s analysis, the city has also conducted a city-wide tree canopy assessment. Koetter described Louisville as having a consolidated city–county government, with 750,000 people living across approximately 400 square miles. “So our purview is broad,” she said. The tree canopy analysis showed that areas with the lowest tree canopy coverage (i.e., downtown, up in the northwest quadrant of Louisville) overlap with areas that have lower socioeconomic status, higher disease mortality rates, and 10-year shorter life expectancies than other areas in the community (see Figure 3-1). Koetter remarked that diabetes and asthma also disproportionately affect this same downtown area. Additionally, people living in areas with lower socioeconomic status bear a disproportionately higher economic burden associated with the changing climate. This is because

NOTE: Maps illustrate overlap in geographic variation in tree canopy coverage, average daily high temperatures (May to September 2012), and mortality from heart disease across the city of Louisville.

SOURCES: Koetter presentation, March 13, 2017; (a) Louisville Office of Sustainability, 2016; (b) created using 2006–2010 Louisville/Jefferson County Death Records Age-Adjusted to 2000 standard population; reprinted with permission from the Louisville Center for Health Equity director, Dr. Kelly Pryor; Louisville Center for Health Equity, 2014; (c) Louisville Office of Sustainability, 2015.

these neighborhoods, Koetter explained, tend to have older housing stock that is less insulated, and thus, residents tend to spend more on utilities for heating and cooling.

Stone’s urban heat analysis showed that areas of the city that feel the heat the most (i.e., based on air temperature readings, which Koetter explained is where people actually feel the heat, as opposed to surface temperature readings) are the same areas that were shown in the tree canopy assessment to have lower tree canopy coverage, worse health outcomes, and shorter life expectancies.

The urban heat management strategies that Stone modeled in his analysis covered greening methods, cooling methods, and all methods combined. His results showed that greening certain areas of the community can reduce heat by more than 2°F. But the amount of greening required to do this, Koetter said, “is not a small task.” Specifically, it would require planting 450,000 trees and installing 730 10,000-square-foot green roofs. Achieving similar benefits from cooling methods, rather than greening methods, would require installing only 23,000 roofs that are 10,000 square feet, but paving 54 miles of road, surface area, parking lots, and other areas with cooling materials. The findings that most surprised and pleased Stone, according to Koetter, were that the effects of all methods combined were far more than additive. For Koetter, these results highlight the need to consider multiple strategies to manage urban heat.

Planting Trees: Effects on Air Pollution and Health

Koetter continued to describe another recently completed Office of Sustainability project, Green for Good, which was funded through a Partners for Place grant. The goal was to install a densely vegetated buffer between a population of people and a heavily trafficked road, and evaluate particulate matter (i.e., in the air) and conduct biomarker sampling (i.e., in volunteers) both before and after installation of the buffer.

After assessing more than 20 properties, the city chose an elementary school as the study site because it was known to have high-traffic pollution and because it had space for planting the buffer. A densely vegetated buffer was planted between the street and the school population, with part of the school yard left unbuffered to serve as a control. In addition to air monitoring, the city also conducted both before and after blood and urine biomarker sampling of 80 volunteer students and teachers at the school. All of the pre-intervention air monitoring and biomarker sampling occurred in September, the planting of the buffer (100 trees) occurred in October, and the post-intervention measurements were collected in November.

The air monitoring showed a 60 percent reduction in particulate matter behind the buffer, compared with the front of the street. The biomarker

sampling indicated that epithelial progenitor cells increased in number, and immune cell numbers decreased. According to Koetter, the biomarker findings are an indication that the buffer worked, and the city of Louisville is partnering with the University of Louisville to develop a preliminary report, with a full study of the results from Green for Good to be published in a peer-review journal.

Next Steps for Louisville

Koetter listed several next steps for Louisville, starting with the city having been recently selected for the final round of the 100 Resilient Cities program, which is funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. According to Koetter, as part of this program, the city’s chief resilience officer will be addressing climate change issues related to health and the environment.

Additionally, Louisville’s Office of Sustainability recently released its Cool Roof Rebate Program for residential and commercial projects, providing $1 per square foot and ranging from $2,000 to $10,000 per project. The goal of the program, Koetter explained, is to inspire and incentivize installation of Energy Star cool roof shingles, which help to not only manage the heat island effect across the city, but also to reduce energy bills. Sixty percent of that funding has been set aside for neighborhoods that feel the most heat (i.e., neighborhoods in the northwest side of the city). The city also offers an incentive for green roofs.

In addition to these cool and green roof incentives, the Office of Sustainability is conducting a cool paving pilot project across the city. Koetter remarked that there are many materials that are cooler or more highly reflective than concrete or asphalt. The pilot project aims to set an example for what materials can be used and how such materials can be laid successfully to withstand four-season weather.

Another pilot project currently under way is the planting of nine trees in a diamond configuration in the center of the parking lot across from the city hall. The area where the trees were planted was topped with porous paving materials so that cars can drive over it without damaging the trees. It is a small-scale project, Koetter commented, but one that will, with success, demonstrate to private property owners what they can do to green their parking lots without losing any parking spots. With respect to the tree canopy at large, the city-wide goal is to achieve 45 percent coverage. Coverage is currently at 37 percent. The focus is on parts of the community where people live. “We really need to inspire citizens, because the most available property is on private lands,” Koetter said.

In addition to roof and paving projects, as well as tree canopy work, the city has been focusing on messaging. For example, the city advertises on city buses to not only promote awareness of extreme heat events, but for

all greening, cooling, and other energy conservation programs across the city (using the social media hashtag #cool502, in reference to Louisville’s area code).

Finally, the city is in the process of updating its comprehensive plan, which Koetter identified as a great opportunity to integrate not just health, but also sustainability, into all policies. In addition, the city is currently conducting a greenhouse gas inventory and will be setting a target reduction goal as part of that process. There is also some interest in predicting the community health effects of the city’s carbon reduction efforts. A final next step, she said, will be to enlist the help of a biostatistician to integrate all of the various types of data that have been collected related to the city’s greening, air quality, and energy efficiency programs, and to health outcomes.

FAITH IN LANDSCAPE STEWARDSHIP2

In a joint presentation, Halida Hatic and Rachel Holmes described a project in Louisville that was co-created by the Center for Interfaith Relations (represented by Hatic), a Louisville-based nonprofit organization that works to promote interfaith understanding, cooperation, and action; The Nature Conservancy (represented by Rachel Holmes); and GreenFaith.

In her opening remarks, Hatic described the project, Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces, as a methodology, or protocol, that was jointly developed by the partners listed above. The intent of the project, she said, is to help communities of faith learn about the ecological benefits of their properties and identify achievable goals to improve their landscapes for both people and nature. Ultimately, the intention is also to help solve some of Louisville’s more challenging problems.

Hatic mentioned that she would be speaking first on the important role that strong partnerships serve in Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces and how cultivation of a shared vision for the project is what led to these strong partnerships. She described these partnerships as mutually beneficial, organic, honest, creative, and most importantly, in her opinion, successful. Then, Holmes would discuss the methodology and tools being used in the project. Hatic commented that the project did not have to “reinvent the wheel” with respect to the tools employed, but they did have to connect and listen to put the tools together in a way that would support a diverse, multifaith audience.

___________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Halida Hatic, director of Community Relations and Development at the Center for Interfaith Relations in Louisville, Kentucky, and Rachel Holmes, conservation coordinator for Healthy Trees, Healthy Cities, The Nature Conservancy.

Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces: The Importance of Mutually Beneficial Partnerships

Hatic referred to Koetter’s description of Louisville’s many challenges, including its poor air quality and the fact that it has one of the fastest growing urban heat islands in the nation. She remarked that, while there is much work to be done, Louisville has also made huge strides in turning these challenges into opportunities to improve the health and well-being of its citizens. Louisville is a leader in the compassionate cities movement and has earned the title of Model International Compassionate City 5 years running. Earning this title, Hatic said, takes a lot of political will and a lot of courage on the part of city leadership. Hatic remarked that in addition to being in the 100 Resilient Cities network, Louisville has offered itself as an “urban laboratory” for exploring problems and possibilities and for sharing its wisdom and experiences with the world.

Finally, for a number of different reasons, according to Hatic, Louisville has a religiously and culturally diverse community with a rich history of celebrating, promoting, and supporting interfaith collaboration and action. For example, the Center for Interfaith Relations hosts an annual event called the Festival of Faiths, which is now in its 22nd year. Through this collaboration and action, there has been much dialogue in the faith community about the issues being addressed at this workshop. Hatic emphasized, as well, that not only are people and communities of faith emerging at the local level, but their voices are emerging globally and as leading voices in the collective environmental consciousness. Framing climate change as a moral issue is not a new issue, in her opinion, and it is one that she predicts will be heard over and over again in the future through voices like those of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Pope Francis.

The genesis of the Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces, Hatic continued, was four people with shared values and the desire to collaborate who were sitting around a table with what Hatic described as “truly noble intentions.” “We had no idea what we were going to come up with,” she said, “but we knew we wanted to do something meaningful together.” At the time, the Center had been partnering with the Cathedral of the Assumption, the Catholic cathedral in Louisville, on an energy audit. In conversations at the table, with The Nature Conservancy present, participants realized that there was nothing equivalent to an energy audit that could be used to assist faith communities with assessing the health and well-being of their living landscapes. Thus, the idea to co-create the Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces methodology was born.

Of the three partners, the Center for the Interfaith Relations was able to bring the people and “street cred,” Hatic said, while The Nature

Conservancy brought the science and technology, and GreenFaith, the amplification.

The Center hosted three in-person meetings, which included feedback sessions and trainings, over the course of the first several months. Volunteers were then sent off to implement the pilot methodology, with support provided by the partners. “It was a pretty simple process,” Hatic said, “but had huge results.”

Four institutions participated in the pilot: Center for Interfaith Relations, St. Xavier Catholic High School, River Road Mosque/Louisville Islamic Center, and Christ Church Cathedral (Episcopal). These organizations, Hatic explained, covered a diversity of locations, in terms of urban versus suburban environments, as well as a diversity of age participants and faith traditions.

In conclusion, Hatic reiterated the importance of checking your agenda at the door for a partnership to be successful. The relationships need to grow organically, she emphasized. She also emphasized the importance of being flexible, starting at a base of shared values, gaining mutual benefit, and having a shared need.

Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces: Usable Tools and Support

Holmes began by expressing what a wonderful privilege it was to be at a workshop where the public health officials are in the majority, not the minority, and it is the conservationists, like herself, who “are representing” their field. She reiterated what Hatic had said about the reality that the Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces partners did not need to reinvent the wheel when developing their methodology. Rather, the methodology and tools came out of work that The Nature Conservancy had been doing with urban forestry across the country and that GreenFaith had been doing with audit programs.

A key to this work, Holmes stated, is to not stop at the data. The key is to analyze and plan for action. “It is not enough just to know what you have out there,” she said. It is more important, she went on, that you know how to manage what you have. She commented on the “beauty” of the process when, for example, someone using a clipboard or app to collect data begins to see not just a wooded area behind a basketball court, but that the wooded area is actually a critical wetland that supports wildlife.

While doing the best they could to leverage tools and methodologies that they knew already existed, the partners also wanted to develop an audit and protocol that were as accessible to as many people as possible. The intention, Holmes explained, was for the audit, when it goes national, to be accessible to anyone, regardless of what funding, skill level, and knowledge base exists in their community.

In sum, the guiding principles for the audit were no cost for participation, simple equipment/protocols, well-supported methods (e.g., videos and fact sheets are available for people who need instruction), accessibility for differently abled people (e.g., some people may not be comfortable outdoors and would rather participate by being indoors, uploading data), and community connectivity (i.e., ensuring that what people are reading about their landscape or gaining from the audit is directly applicable to partners in the community).

The audit has four components: (1) tree canopy assessment, (2) landscape mapping, (3) grounds management, and (4) worship/community. As an urban forester, Holmes expressed excitement that, during the initial focus group sessions, people prioritized tree canopy assessment. She noted that, in addition to the information presented by Jonathan Patz, another important role for trees is the absorption of particulates. The tree canopy assessment component of the audit encompasses not just identifying what trees are present, but also where they are situated and, more importantly, how healthy they are, including whether they are being affected by any insects or diseases that are known threats to the urban tree canopy (e.g., the emerald ash borer).

Holmes also highlighted the worship/community component of the audit, which, she explained, involves using a basic questionnaire to ask if concepts of nature and stewardship are being integrated into liturgical practices whenever possible. Or, instead, do these concepts only surface around Earth Day? There may be other opportunities for talking about what it means not just to love nature, but to take care of nature.

Currently, the project partners are in the process of taking the information and feedback received from the pilot and making updates and diversifying opportunities. Holmes said they are envisioning a fall 2017 or spring 2018 national launch.

Holmes reiterated Hatic’s message to “check your agenda at the door.” The Nature Conservancy, she said, did not enter the door and say, “Here’s a tool. Go ahead and use it.” Rather, they asked what information would be beneficial to the community. She quoted participants from two partner organizations, one from the Louisville Islamic Center’s Brother Sikhander Chowhan who said, “If you don’t care for your place of worship . . . that’s in a way disrespectful to our Creator.” The second quote was from the Very Reverend Joan Pritcher of Christ Church Cathedral (Episcopal), who said that opportunities like the audit “appeal to people we aren’t as successful reaching through traditional faith community activities.”

In closing, Holmes contrasted people’s motivations from a faith perspective (redemption, forgiveness, stewardship, ritual, preaching, enlightenment, praise, prayer) versus those from a conservation perspective (restoration, mitigation, stewardship, best practices, teaching, analysis, celebration) and

asserted that, regardless of whether you are drawn to conservation because you are motivated by a belief or, instead, by ethical humanism, “it’s time to join the discourse.” She was aware that many people feel uncomfortable using specific (e.g., religious) words in conversations about landscape stewardship. It is okay, she said, to say, for example, “I pray,” adding about herself, “I’m a conservationist. I’m in the pew on Sunday, but I’m out in the field on Monday.” She urged participants to show leadership in bridging these motivation and language gaps.

EMPOWER KENTUCKY3

Empower Kentucky is an effort to shape a people’s energy plan for the state of Kentucky, Lisa Abbott began. The project was launched immediately after the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced its Clean Power Plan, which state political leaders from both sides of the aisle opposed, according to Abbott, with both candidates for governor vowing to not comply if elected. Thus, it was thought that perhaps a grassroots social organization could take on the challenge and, through a meaningful public process, develop a plan with outcomes that are better for health, better for jobs, and better for average [utility] bills; advance a just transition for affected workers; advance racial and economic justice; and comply with the Clean Power Plan. “So that’s what we set out to do—no small task,” Abbott said.

Abbott described Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, the parent organization for Empower Kentucky, as a 35-year-old grassroots organizing group working for a better quality of life for all Kentuckians and for a vibrant and healthy democracy. KFTC believes, Abbott continued, that right now in Kentucky, as well as elsewhere around the world, a real opportunity exists to shape a just transition to a clean energy economy. The year 2015 was the first time that coal’s share of Kentucky’s electrical energy generation fell below 90 percent, to 87 percent. Although the energy and political landscape supported by coal have been in place for decades, Abbott remarked that it is changing rapidly due to many factors, including that the state’s aging fleet of coal plants is retiring. She said, “All of our energy eggs have been in one basket for decades. . . . We have a choice about . . . the next economy . . . [and] the next energy system.”

The stated goals of Empower Kentucky are to generate political will for a just transition to a clean energy future; meaningfully engage thousands of Kentuckians; develop an environmental justice analysis for Kentucky; and develop a people’s plan for Kentucky’s energy future. Abbott clarified that

___________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Lisa Abbott, organizer, Empower Kentucky, Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, London, Kentucky.

she would be presenting preliminary results and that the results and report would be released in mid-April 2017.4

A Grassroots Effort to Change Kentucky’s Energy Future: The Importance of Process

“In times of transition, process really matters,” Abbott emphasized. It matters, she continued, that people have their voices and stories heard and that there is input and discussion. Thus, among other parts of the Empower Kentucky public process, KFTC organized community conversations in all six congressional districts of Kentucky in spring 2016. The conversations were 3-hour programs that included locally sourced meals and facilitated table discussion.

The community conversations began with asking participants to spend three minutes each telling the story of relationship with Kentucky’s energy system. Abbott described the “intimate” relationship that Kentuckians have with the state’s energy system—one stemming not just from the work they have done in the mines, but also the asthma they have experienced, the trouble they have had paying their bills, and the host of other ways people’s lives have been deeply connected to the state’s energy system. If KFTC were to have started the community conversations by talking about abstractions, they would have missed the opportunity to learn about these connections. Following the sharing of stories, participants were asked to address some key specific questions: What is your vision for Kentucky’s energy future? What do you think that will take? How can we ensure that all Kentuckians will benefit and that no one is left behind as we transition to a clean energy economy? Every seat at every table at every community conversation was filled, Abbott remarked. The seats were free, she noted, but residents had to reserve their seats ahead of time.

In addition to these community conversations, KFTC also conducted an online survey and house meetings. A total of 750 people took part in the community conversations, and 1,200 people from across the state provided input into the plan. Abbott described the effort as “very intentional” in encouraging input from a broad and diverse range of communities.

Among other results, when asked about their vision for Kentucky’s energy future, residents expressed a very strong interest in renewable energy, especially solar; health; job creation; and the opportunity for a just transition for workers from the fossil fuel industry.

In addition to seeking public input, Empower Kentucky also undertook its own economic justice analysis. Abbott explained that when it issued the

___________________

4 See http://www.empowerkentucky.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Empower-Exec-Summary-Report-final-1.pdf (accessed January 5, 2018).

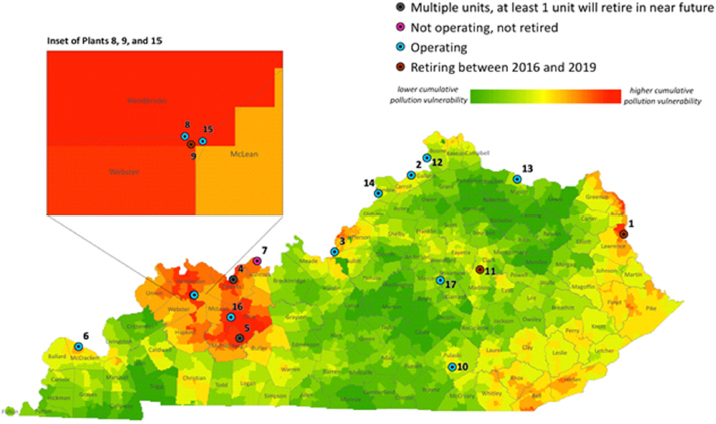

NOTE: Operating and retiring coal plants in Kentucky, overlaid by cumulative pollution (i.e., as measured by about a dozen indicators of pollution, not all of which are related to the energy system [e.g., lead exposure]).

SOURCE: Abbott presentation, March 13, 2017. Reprinted with permission from Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, 2017.

Clean Power Plan, the EPA required that states have meaningful public engagement, but did not define that engagement, and they recommended that states do their own environmental justice analyses. Empower Kentucky’s environmental justice team is composed of about a dozen volunteers from around the state, led by a recent graduate of University of Kentucky. Abbott showed the map of coal plants in Kentucky with an overlay showing cumulative pollution (i.e., as measured by about a dozen indicators of pollution) (see Figure 3-2) as an example of the findings that have emerged from the environmental justice analysis. Abbott pointed out that the two areas where coal mining takes place (one in the east, the other in the west) also have the greatest cumulative pollution, and people living in the western part of the state are doubly exposed to both extraction and burning.

The People’s Plan: Framework, Recommendations, and Predicted Outcomes

Out of the public process, combined with results from the environmental justice analysis, Empower Kentucky is developing a People’s Plan

(released several weeks after the workshop, in April 2017).5 The plan’s framework has seven components: (1) accelerate energy efficiency and renewable energy across the state’s economy; (2) create jobs and support a just transition; (3) prioritize health and equity; (4) support local solutions; (5) invest fully and fairly in the energy transition; (6) meet our obligations to the climate; and (7) engage everyone to change other essential systems. Regarding the last component, Abbott explained, it is not just the energy system that people across the state want to change. They also want to change the food system, transportation, and other essential systems.

The plan is long, Abbott said, with recommendations encompassed within each of the seven components above. She described a few key components. First, the plan recommends that Kentucky significantly ramp up its efforts in energy efficiency in order to save, over a 15-year period (i.e., by 2032), 15 percent6 of what would otherwise be consumed, with a strong emphasis on achieving 18 percent savings through programs that directly benefit low-income households. Second, the plan recommends that Kentucky meet a 25 percent renewable energy goal, with at least 1 percent coming from distributed solar. Third, the plan recommends putting a price on carbon. This recommendation was made for two reasons: first, to generate revenue to invest in a just transition for coal workers and coal communities, and second, because an analysis conducted by consultants showed that even if Kentucky were to reduce the amount of “dirty energy” being used by Kentuckians, neighboring states would continue to buy Kentucky’s coal-fired power. In other words, Abbott said, “We would become the designated smoking area.” Attaching a price to carbon will make their coal power more expensive and less competitive in the regional market.

Empower Kentucky participants examined many possible prices, Abbott explained, including the Obama administration estimate that the true cost of carbon is just under $40/ton. They chose to recommend a low $1–$3/ton, because it was determined that a higher price would accelerate the rush to natural gas and that this lower price was sufficient to reduce emissions and achieve the 15-year goal for implementing more renewable energy and for more energy efficiency. A fourth key recommendation of the plan is to not allow biomass to count as “low carbon” or “carbon neutral.”

The preliminary predicted outcomes,7 by 2032, include

___________________

5 The People’s Plan was released in April 2017 and is available at http://www.empowerkentucky.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Empower-Exec-Summary-Report-final-1.pdf (accessed May 26, 2017).

6 The numbers shared were preliminary. In the Final Empower Kentucky Plan this percentage is 17.

7 See http://www.empowerkentucky.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Empower-Exec-Summary-Report-final-1.pdf (accessed January 5, 2018).

- More jobs than business as usual (46,300 more job years);

- Improved health (from lower sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions);

- Lower average bills ($13 less than business as usual);8

- The generation of nearly $400 million to be reinvested in a just transition for coal workers and coal communities;

- A 36 percent reduction in CO2 emissions from the power sector (the Clean Power Plan’s goal for Kentucky was 31 percent, so this slightly exceeds that goal, Abbott noted);9

- An $11 billion investment in energy efficiency; and

- A priority on low-income and industrial energy savings.

Some additional predicted outcomes are that fewer gas plants will be built, compared with business as usual; the same number of coal plants will be retired, compared with business as usual, but with the existing fleet being used less than it is now (i.e., the direction the state is heading, Abbott explained, is that old coal plants are being retired regardless of whether “we do good things”); [production facilities for] another gigawatt of solar and another 600 megawatts of wind will be built; and less electricity will be imported, compared to business as usual.

The People’s Plan as a Foundation for Future Work

Abbott acknowledged the very difficult political environment into which these outcomes will be released, both at the national level and within Kentucky. She encouraged viewing this plan as part of creating a broader political will to “do good things” and produce better outcomes for Kentuckians in terms of jobs, health, bills, and the climate. The intention is to use the People’s Plan as a foundation for alliances, collaboration, and campaigning across the state.

“We see the biggest opportunity at a very local level,” Abbott said. She mentioned, as examples, calling on utilities in Louisville to achieve greater energy efficiency, and other local campaigns to get more all-electric buses on the streets.

Already, Abbott observed, the Empower Kentucky process has strengthened the network and political will in Kentucky to resist moving in a direction that could be detrimental to health and well-being, and to continue to work for policy change “where we can.” She mentioned a very powerful

___________________

8 In the final Empower KY Plan, the average residential bill would be 10 percent less than under the business as usual scenario and the percentage was used rather than $13.

9 In the final plan, CO2 reduction is 40 percent by 2032 (from 2012), not 36 percent. All other numbers remained as reported at the workshop.

senator in the state legislature having recently introduced a bill that would have decimated Kentucky’s homegrown solar industry, which Abbott said is small, but growing. However, the senator was so shocked by public outcry that he removed the bill. She concluded, “This project, I think, can produce some of those kinds of results.”

DISCUSSION

Following Abbott’s talk, panel moderator Rudolph commented on the “inspiring” nature of the panelists’ talks in terms of what can be done through local action to address these problems in a positive and constructive way. Then, the four panelists participated in an open discussion with the audience.

What Can the Health Sector Do to Help Local Efforts?

Rudolph remarked on the urgency of taking transformative action quickly, given that, she said, “We are blowing through what scientists call ‘the carbon budget,’” and the reality is that each day action is not taken, the risk for more catastrophic climate change and its impact on future generations increases. Given this urgency, combined with the highly conservative political environment of Kentucky, Rudolph asked about the role of the health sector to help “move things along faster and scale things up.”

Koetter responded that while the team at the University of Louisville has been a great help to the Office of Sustainability with respect to helping city officials understand the health data that have been collected, she encouraged a greater understanding of the effects of climate change on their part and among all health care professionals.

Hatic encouraged a more holistic perspective of health. Spiritual health is just as important as physical health, environmental health, and economic health, in her opinion. She said, “We can’t dissociate one from the other.”

Abbott offered that her message would be, “Be bold and really stand with communities that are facing these issues on the ground.” She mentioned having attended a conference in Louisville on improving air quality in the city a few years before this workshop. The conference was attended by about 300 people from many sectors, and the day was packed with workshops, speakers, and good data and information about the health impacts of poor air quality. But the word “coal” was never mentioned, she recalled. She cautioned that if the only voices willing to talk about the evidence regarding what is actually causing some of the most significant health impacts are “voices on the margins of political power,” it will remain very difficult to build political will. She encouraged people in positions of power,

whatever power that may be, to “be bold enough together to say what is truly going on and what is needed.”

Building Political Will

When asked by Catherine Baase of the Michigan Health Improvement Alliance what the state government’s reaction to Empower Kentucky’s People’s Plan has been and what the next steps for the plan will be, Abbott replied that a primary goal will be to build political will. When the final plan is released, KFTC will be holding public briefings and presentations, as well as meetings with individual leaders. In addition to encouraging what she envisioned as incremental policy changes, her other hope for the plan is that it will be used by people who are thinking about running for office in 2018 or 2020. Candidates can “grab onto” some of the ideas and outcomes in the plan, she envisioned, and communicate to Kentuckians specific steps that can be taken to create jobs, save money, and improve health.

While on the topic of political will, Rudolph asked Koetter where the political will in Louisville is coming from for the Office of Sustainability work that Koetter described. Koetter credited the city’s strong local leadership and awareness, including the mayor, who formed the Office of Sustainability when he entered office in 2011.

Mary Pittman of the Public Health Institute then asked about strategies for state-wide scaling up of some of what has been done in an urban environment given that, she said, “the culture of coal country is a bit different than an urban center.” She agreed that part of the challenge is political will, but opined that another part is this culture shift. Hatic responded by telling a bit of her own personal history, including her move from Boston to Kentucky and her initial work with energy management programs in 30 school districts across eastern Kentucky. One of the things she quickly learned, she said, was that even if the adults sitting around the table did not buy into the “green movement,” their kids did. She expressed a great deal of hope for the next generation, even in Appalachia, where people are beginning to recognize “the importance of the earth . . . and the fact that what I do to my planet, I am doing to myself.”

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast every time,” Abbott quoted, and agreed that culture matters and stressed the importance of messaging and organizing messengers. “Who is helping to bring the messages forward really, really matters,” she said.

Engaging the Private Sector

When asked by John Bolduc, an audience member and environmental planner for the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, how the business com-

munity is responding to work described by the panelists, Koetter described the response as “mixed.” She mentioned that the several Fortune 500 companies that are headquartered in Louisville maintain corporate responsibility, but many local businesses have not been as receptive because of concerns about regulation. That said, however, some have been a little more receptive to the tree canopy work, for example, asking for help on where to plant trees on their property.

Hatic added that both she and Koetter sit on a local nonprofit called the Louisville Sustainability Council. Many of the larger businesses in Louisville are represented, so “they’re showing up at the table,” she said.

Natasha DeJarnett, an audience member from APHA, asked the panelists for insights into how to facilitate public–private partnerships for moving climate action forward. Hatic reiterated a key message from her presentation: “Check your agenda at the door.” In addition to establishing good buy-in, she said, “it’s all about relationship.” She clarified that she meant not just relationships with others, but also relationships with ourselves and with the earth. She encouraged talking about “how [we] can work together through our shared values and our shared needs to create something that will be positive and sustaining.”

Engaging Religious Networks

Gary Gunderson of the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center and Stakeholder Health identified himself as a Baptist minister and mentioned that he works with many faith-based health care systems. He asked Hatic and Holmes about the capacity of the Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces program to engage other religions or religious organizations, such as the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and particularly some of the more conservative religious networks.

Holmes replied that such engagement has to do with how issues are framed. The challenge, she said, is to find out what matters to the communities that you are working with and then frame the issue in those terms. For example, if the issue is water quality, while water quality has both upstream and downstream issues that need to be addressed, she asked, “What do people care about?” They care about the water in their glass, she answered. They are not necessarily thinking about the forested areas that are protecting the watershed that produces that water. In her opinion, it is not that other religious networks are not engaged. Rather, the challenge is to find out how they are engaged and how that engagement aligns with mutual goals. She added that although Pope Francis is considered by many to be the “poster child” for modern environmental consciousness of faith-based institutions, in fact, it was the evangelicals who “put faith-based environmentalism on the map.” Their environmentalism can be traced back

to St. Francis and Thomas Aquinas, perhaps even Jesus, Holmes suggested. Thus, she emphasized, a foundation exists for these partnerships to be formed.

Hatic described the environment as a “unifying” topic, not an issue that separates, and that conversations leading up to the Landscape Audit for Sacred Spaces were not new. She remarked that much of the dialogue at the Festival of Faiths event in Louisville, which the Center for Interfaith Relations has been hosting for 22 years, revolves around the environment. She added that the Center is constantly reaching out and inviting everyone in the community to the table and that responses and audience members are different from year to year. In fact, she said, the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary was represented at a talk hosted by the Center a couple of years ago. “The seeds are being planted,” she said, but “it takes a little while for them to germinate.”

A Just Transition from Traditional Energy

Finally, much of the discussion at the end of this first panel revolved around the impacts of transitioning from traditional energy and the concept of a just transition. First, a member of the workshop audience, Kelly Dennings, asked the panelists how their organizations were addressing the transition of Kentuckians from the traditional energy sector with respect to mental health and other components of health.

Koetter replied that the Louisville Office of Sustainability’s goal is to reduce energy use per capita by 25 percent by 2025. As she had said during her talk, she mentioned again that hopefully, they will be engaging a biostatistician to help them understand how the improvements in air quality resulting from this reduced energy use will impact health. She encouraged putting health first when promoting energy goals as a way to defray some of the political sensitivity around the issue.

Since 2009, Kentucky has lost about 13,000 coal mining jobs, Abbott responded. The mining communities were already among some of the nation’s poorest, even when the coal industry was doing well, she said, so the loss of the sector and the loss of the best paying jobs has hit the communities hard. “They are struggling on multiple levels,” she said. The hit includes not just loss of revenue, but population loss and mental health impacts, including drug abuse issues. Their resilience to deal with some of these impacts is greatly challenged. She noted that the former federal administration made some small, but important, investments, and suggested that much more could be done by both the federal government and the state of Kentucky to provide comprehensive support for these communities. For example, KFTC is working to pass federal policy that would direct about $1 billion to land and stream restorations, which would have ecological

benefits and would be a job-creating force. In addition, Abbott underscored the need for support not just for the coal workers, but also for female heads of households who have never had good economic opportunities in these communities. She said, “Thinking about a just community has to include the directly affected workers, but also the broader community in which they live.”

Dick Zimmer of Zimmer Strategies asked Abbott to elaborate on what she meant by “just transition” and what other opportunities exist for an unemployed coal miner besides stream restoration. Abbott explained that the term “just transition” comes from union movement language, specifically discussions about plant closures. In the context of coal mining regions in central Appalachia, KFTC is working to broaden the term to include the whole community in addition to the affected workers. She reiterated that the economies in these communities experience some of the most persistent and deepest poverty in the nation. She said, “The whole region is in need of a just transition.”

KFTC has developed a number of principles and a set of policies that illustrate what a just transition would look like, Abbott continued. “We don’t have all the answers,” she said, but there are some things that could be done today to support a just transition. These include supporting some of the foundational parts of any healthy community, such as a strong health safety net, strong local schools, opportunities for meaningful job training, and investment in job creation. Importantly, she said, a just transition also includes providing job-sustaining support for workers who, for example, have been working on the railroads for 17 years, but have recently been laid off because there is so much less coal being transported, and therefore will not receive their 25-year guaranteed pension. There has to be a public investment in supporting these workers to bridge them to the point of retirement, she argued.

Although the economy as a whole is not healthy in eastern Kentucky, there are opportunities, Abbott said, and many unemployed coal workers have skills that can be redirected toward other careers that can provide family-sustaining wages. Land and stream restoration is one opportunity, which has as its goal repairing some of the legacy of extraction. Other opportunities exist in sustainable forestry, renewable energy growth, health care, tourism, and arts and crafts.

Patricia Martz, a member of the workshop’s remote audience from Edmonton, Alberta, offered two examples of a just transition outside of Kentucky. The first was tobacco farmers in the southern United Sates who no longer grow tobacco, rather chickpeas, and who also, as a “bonus,” the audience member noted, no longer chew tobacco, rather chickpeas. The second example she cited was the closure of the logging and timber industry in Leavenworth, Washington, where, in 1962, Project LIFE (Leavenworth

Improvement for Everyone) was formed in partnership with the University of Washington to investigate strategies to revitalize the struggling logging town and where the old logging and timber jobs and economy were diverted into tourism.

Zimmer also asked about the role of nuclear power in the Empower Kentucky plan. Abbott explained that Kentucky has banned nuclear power since the 1970s, and while there is an effort in the legislature to remove the ban, Empower Kentucky did not consider it. It was mentioned occasionally, Abbott said, in KFTC’s conversations around the state, but “let’s never advance it” is mentioned as frequently as “let’s advance it.” She mentioned that one of the state utilities, Kentucky Power, recently analyzed its next 15 years and ruled out nuclear power as an option because of its expense.