2

Biomarkers of Neuroinflammation: Challenges and Potential Opportunities

Neuroinflammation is a pathological feature of a wide range of central nervous system (CNS) diseases, including classic neuroinflammatory disorders, such as multiple sclerosis (MS); neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Huntington’s disease (HD); disorders induced by brain injury; and neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia. Brian Campbell said that similar cell types and inflammatory mediators are induced across the range of these disorders, yet the consequences vary from toxic processes, such as the release of proinflammatory cytokines or reactive oxygen species, to reparative processes, such as the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines or stimulation of neuroprotective and angiogenic factors. These inflammatory mediators and other cellular markers could all potentially represent biomarkers of neuroinflammation, which in turn could be used to elucidate mechanisms, suggested Campbell. However, many workshop participants cited challenges that have hindered the development of such biomarkers. They also cited innovative approaches and collaborative efforts that are seeking to overcome these challenges.

OVERVIEW OF CHALLENGES

The Complex Biology of Neuroinflammation

Campbell described a neuroinflammatory process that is highly complex in terms of the activation of microglia, which are the resident immune cells of the brain; the cellular microenvironment, which includes not only microglia, but also astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and peripheral-

ly derived immune cells; and the temporal correlation between different activation states of cells and disease phenotypes. In the absence of disease, neuroinflammatory and immune cells help maintain homeostasis, said Campbell. Amit Bar-Or, professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, added that there is currently no comprehensive, functional immune profiling of the normal state on which diseases are superimposed. Added to this complexity is a limited understanding of the basic biology of microglia as they transition from resting to activated states and the completely unexplored role of the microbiota on microglial biology, said Gary Landreth, professor of anatomy and cell biology at the Stark Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine. The role that T cells play in neuroinflammatory diseases, including neuropsychiatric diseases, is also limited, despite the fact that T cells are known to play a major role in neuronal integrity, added Andrew Miller, William P. Timmie Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Emory University School of Medicine.

The complexity of neuroinflammation is exacerbated by substantial biological heterogeneity across individuals and over the disease course, including differences in the subsets of immune cells activated, said Campbell. Heterogeneity is seen not only in the types of cells but in their spatial and temporal appearance and functional activity states during development in healthy individuals as well as in normal aging and disease, added Linda Brady. She cited several aspects of neuroinflammation where a more detailed understanding is needed: (1) the response of immune cells and endothelial cells to the local microenvironment, (2) localized inflammatory responses, (3) the range of phenotypes in functional activity states of microglia and immune cells in normal and non-disease tissue over the life span of development, (4) the role of acute and chronic inflammation in homeostasis and disease states, and (5) under what conditions neuroinflammation has positive versus negative effects.

Given the complexity of neuroinflammation across the acute to chronic continuum in different diseases, different strategies may be needed to develop biomarkers that will both elucidate the pathophysiology of disease and be useful for therapeutic development purposes, said Edward Bullmore, who heads the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Cambridge and the Clinical Unit for GlaxoSmithKline in Cambridge. He added that there is also likely to be a need for more attention to statistical methods and computational tools, including novel tools to analyze high-dimensional data.

Exploring the Need for Better Biomarkers

Although some positron emission tomography (PET) ligands are available that recognize a neuroinflammatory signal, markers are not currently available to characterize different activation states of microglia, nor the consequences of microglia activation, such as whether they become more phagocytic, said Beth Stevens, associate professor of neurology at Harvard University Medical School; Boston Children’s Hospital. PET ligands are also available to assess synaptic density, but Stevens said there is an urgent need for biomarkers of synaptic dysfunction, which could be particularly valuable for neuropsychiatric disorders where the affected circuits are not known. Markers of synaptic dysfunction not only could help identify those circuits and profile the normal condition and region-specific heterogeneity but could also provide information about when those circuits are affected, said Stevens. Biomarkers are also needed to identify regional variation in blood‒brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction, added Richard Daneman, assistant professor of neuroscience and pharmacology at University of California, San Diego.

Campbell questioned whether any of the existing imaging biomarkers have adequate sensitivity in diseases where neuroinflammatory changes are subtle, such as depression, or to discriminate subpopulations and their changing microenvironments in diseases such as AD. Even when biomarkers are available, their relationship to disease course is unclear, said Bullmore, noting that cytokines and gene transcripts have been associated with CNS diseases, including depression, but association does not necessarily mean causation. He said this explanatory gap needs to be filled with mechanistic studies. In addition, longitudinal studies that look at a broad range of risks and phenotypes over time in relation to the emergence of depression and changes in peripheral biomarkers of inflammation could provide further information on the mechanisms involved, he said.

An audience participant noted that because neuroinflammation can produce both damaging and compensatory effects, it is critical to understand both the normal trajectory of pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules and signaling mechanisms as well as the extent to which activation of microglia and other immune cells represents a compensatory mechanism in a disease process. Miller suggested that researchers investigate under what conditions increased expression of these molecules reflect neuroinflammation versus normal physiological processes, such as synaptic plasticity.

Plasma-based peripheral biomarkers of inflammation would be less expensive, less invasive, and more accessible than central biomarkers measured in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or through neuroimaging approaches, although central biomarkers may be closer to the disease site, said Bullmore. However, he added that resolving the tradeoff between these two approaches will require more data to make comparisons and establish links between the peripheral and central compartments.

Using Appropriate Animal Models

Animal models are widely used to study neuroinflammation, yet have limitations with regard to biomarker development. For example, Bar-Or said that, while animal modeling in MS has elucidated some important principles of immune regulation, trafficking, and neuronal interactions, there is no animal that develops actual MS, posing a challenge to elucidating certain pathophysiological aspects and developing targeted therapies.

Fiona Crawford, president and chief executive officer of the Roskamp Institute, described many animal models that have been explored to study traumatic brain injury (TBI). These models vary in terms of the genetic strain as well as by variations in the way the injury is induced. Mouse models have several advantages, including their accelerated life span and the availability of different strains of genetically manipulated animals. Nevertheless, while all of the preclinical models of TBI and human cases demonstrate inflammation, rodent models cannot show the hallmark chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology of tau in the depths of the sulci, said Crawford. However, they do show other pathological features, including axonal transport issues, the presence of amyloid precursor protein, myelin loss, astrogliosis, and inflammation microgliosis, and they also show behavioral manifestations, such as decline in memory performance.

OVERVIEW OF POTENTIAL OPPORTUNITIES

Developing Static and Dynamic Biomarkers in Parallel

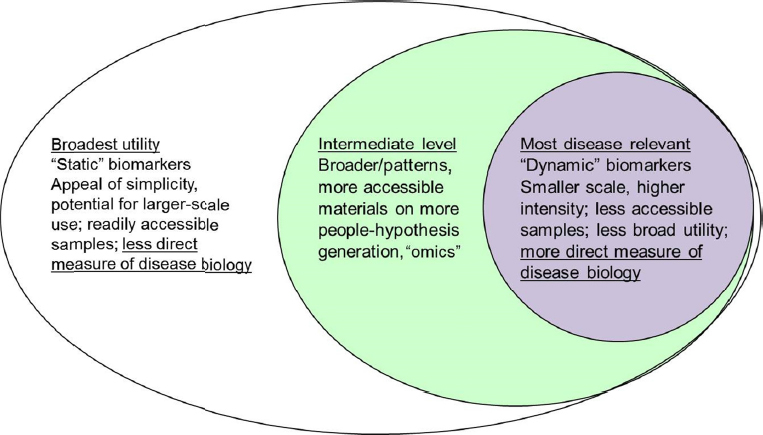

In the context of therapeutic development, biomarkers are needed for multiple purposes: to diagnose disease, monitor therapy, and demonstrate target engagement in clinical trials. Bar-Or proposed an onion-peel model

of biomarker development (see Figure 2-1), in which more broadly applicable “static” biomarkers assessed with more easily accessible samples and technologies may be implemented in all cohort participants, while additional less accessible but potentially more disease-relevant “dynamic” biomarkers are developed in subsets of the cohort where practical. Intermediate biomarkers, such as those obtained from “omics” studies applied to easily accessible samples, can help generate hypotheses that guide dynamic biomarker development, he said.

Bullmore suggested that in clinical trials for anti-inflammatory drugs in non-psychiatric disorders, much earlier end point measurements of brain function and mental state changes should be adopted. If strong evidence could be generated showing that an anticytokine treatment had effects on brain function and mental state that preceded its effects on physical health, this would provide clear evidence of a mechanistically specific event, he said.

SOURCE: Presentation by Bar-Or, March 21, 2017.

Developing Both Central and Peripheral Biomarkers

In terms of biomarker development for neuropsychiatric diseases where peripheral inflammation appears to play a role, Bullmore advocated for transcriptional or functional rather than cytokine assays because there is so much variability in cytokines and proteins in the peripheral blood. However, Miller noted that in non-neuropsychiatric inflammatory diseases, including cardiovascular disease, a protein marker called C-reactive protein (CRP) has proven to be a very strong predictor of disease development and also maps to changes in the brain. Bullmore said that focusing on the peripheral immune system increases the potential availability of biomarkers to guide the selection of patients and assess efficacy, which would reduce the risk of expensive late-stage clinical trial failures that have plagued CNS drug development. An audience participant added that peripheral biomarkers could provide better understanding of the dialogue between the brain and the immune system, for example, how exercise and environmental enrichment may impact depression.

Developing Novel Biomarkers of Neuroinflammation

While many neuroinflammatory mediators have been identified and are being developed as potential biomarkers, additional novel markers are emerging as understanding of the complex mechanisms involved becomes more refined. Stevens suggested that profiling proteomic and ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing in microglia and other cell players in affected versus non-affected brain regions over time could enable identification of novel sets of markers that could tell researchers more about function. She is currently collaborating with Steven McCarroll, director of genetics for the Broad Institute’s Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research, to develop a molecular fingerprint of changes that occur in microglia from patients with HD and other diseases using the novel Drop-seq technology developed in his lab. Drop-seq allows for the study of cells in ways not previously possible, noted Landreth. Bullmore added that it could potentially be applied to thousands of cells obtained in a clean CSF tap to characterize phenotypes of cells close to the brain.

Other suggestions for potentially novel biomarkers include

- New PET ligands or imaging markers that could provide more information about microglia function and synaptic dysfunction (Stevens).

- Biomarkers obtained by examining both soluble phase and cell-based compartments, using tools that can be validly applied and validated in carefully cryo-preserved samples (Bar-Or).

- Biomarkers obtained by activating live cells to bring out disease-related and treatment-related differences (Bar-Or).

- Biomarkers obtained to test BBB disruption, activation of coagulation, and vascular alternations (Akassoglou, Daneman).

New Strategies for Biomarker Development

Given the complex mechanisms of neuroinflammation and its involvement in both healthy and disease states, many workshop participants stated that new strategies are needed to collect and analyze relevant data for biomarker development. Among the suggestions noted by individual workshop participants were:

- Steven Hyman, director of the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University, commented on the importance of collecting normative data for CSF markers, suggesting that understanding of many CNS disorders could be advanced substantially if serial CSF draws could be obtained from a normative developmental cohort.

- For neuropsychiatric diseases, Miller suggested subgrouping patients and looking at their responses to different treatment paradigms.

- Richard Perrin, assistant professor of neuropathology at the Washington University School of Medicine, noted that because aberrant synaptic pruning is common to all neurodegenerative diseases and probably psychiatric diseases that are not considered neurodegenerative, it will be important to learn from all of these diseases and use assays across disease fields.

- Bar-Or commented on the need for an iterative process, using animal and human studies to inform each other, rather than a siloed approach.

- Bullmore commented that because immunotherapeutics now comprise a large proportion of drugs in development for oncology and other disease areas, there is potential to leverage existing expertise, facilities, and molecules, and/or repurpose immunotherapy drugs already on the market for the treatment of CNS diseases.

- Because there appear to be links between inflammatory mediators and depression, Bullmore suggested that future clinical trials of anti-inflammatory drugs for non-psychiatric disorders include brain function and mental-stage changes, in addition to biomarkers of inflammation.

- Miles Herkenham, chief of the Section on Functional Neuroanatomy at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), suggested that lymphocyte profiling might also represent a useful biomarker because the adaptive immune system has been shown to affect mood and, in animals, to improve hippocampal neurogenesis, which may be relevant in depression.

- Although several workshop participants spoke about the limited funding currently available for research on neuroinflammatory diseases, one audience participant commented that funding is available through the Department of Defense for Gulf War illness research, including research related to TBI.

Collaborative Approaches for Biomarker Development

Several workshop participants mentioned frequently that collaboration was a necessary strategy to advance the development of neuroinflammation biomarkers. For example, Stevens advocated for building mechanisms to bring people together to collaborate and share samples, expertise, and data. While collaborations are discussed further in Chapter 7, some of the specific examples cited include the following:

- William Potter, senior advisor to the director at NIMH, noted the benefits of integrating studies conducted across stages of disease and across species. Stevens added that this approach may require a consortium, picking out three or four target mechanisms and looking at them from different perspectives and areas of expertise in multiple animal models and humans.

- Katerina Akassoglou, senior investigator at the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), suggested conducting longitudinal studies in large, well-defined patient populations, such as the Expression, Proteomics, Imaging, Clinical (EPIC) MS cohort at UCSF.1 This

___________________

1 For more information see http://msepicstudy.com/epic (accessed July 17, 2017).

-

cohort includes primary and secondary progressive MS patients at multiple time points.

- McCarroll proposed a definitive experiment to look at the relationship between cell-type-specific RNA expression and imaging data levels for TSPO (translocator protein) or other putative markers of neuroinflammation in order to determine the true cellular sources of these biomarkers. Tarek Samad, head of neurodegeneration at Pfizer Inc., and Perrin advocated for expanding this approach beyond TSPO.

- McCarroll also suggested collaborations to apply Drop-seq technology to better understand the full set of cellular and molecular events in disease states, including which cells produce particular biomarkers, and how the expression of these markers varies among patients. He added that due to ongoing innovations in the Drop-seq technology, such experiments are now possible whenever archival, fresh-frozen brain samples have been saved.

- Perrin said biospecimens from the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University are available for appropriate studies. He said that although tissue from the hippocampus is limited because of its small size in humans, tissue from other brain areas is more readily available.

- Because subject recruitment presents a major challenge to evaluating PET ligands in depression and AD, Robert Innis, chief of the Molecular Imaging Branch at NIMH, offered to work with investigators in this area by providing free PET scans at NIMH facilities to patients in whom plasma and CSF biomarkers have been assessed.

This page intentionally left blank.