Brian Campbell commented that the search for biomarkers encompasses two different objectives: (1) to understand more about the pathophysiology of disease process and (2) to find biomarkers that could be useful in terms of predicting treatment response. These two objectives may merit different strategies, he said. Edward Bullmore suggested that this challenge will be easier to manage for therapeutically focused biomarkers by selecting a particular molecule and then identifying a few biomarkers relevant to the target. Amit Bar-Or noted that although the therapeutic context may provide a more focused opportunity to look at a target or pathway, it could still fall short of elucidating the relevant biological pathways. He argued that a more comprehensive model will be needed to capture the cellular responses and related molecules that comprise pathways. Richard Perrin added that more foundational work is also needed before the neuroinflammatory markers can be used intelligently in clinical trials, adding that he believes the field is close to achieving an adequate understanding of neuroinflammation to move forward.

Tarek Samad said that in order to meet the above objectives, other challenges will need to be addressed: selecting appropriate disease subpopulations, determining the stage or stages of disease to investigate, selecting appropriate measuring tools, and defining a positive outcome with regard to measuring brain neuroimmune tone. While these gaps suggest a development pathway that focuses on disease biology, Samad said that in order to gain enthusiasm and traction from the pharmaceutical industry, a well defined clinical path forward will be required. Bar-Or suggested that there may be a way to combine the broad strategy that Samad mentioned with a shorter-term strategy that could provide incentives for industry. This should include concerted efforts to (1) look at markers in both the periphery and the central nervous system (CNS), he said, including soluble phase markers in both the CSF and blood, as well as cell-based markers, and (2) examine both disease-related and treatment-related differences.

William Potter reiterated what several speakers mentioned throughout the day, that one of the biggest areas of need is biomarkers that can stratify subtypes of patients in treatment for psychiatric or neurological disorders. However, he said there is less agreement on the best way to identify these biomarkers. One option would be to predefine a set of potential analytes and use multiplex technologies, such as expression profiling, proteomics, or other omics approaches, to build composite measures that would allow stratification of individuals. Alternatively, a more hypothesis-driven approach could be used to develop a better under-

standing of the function of different cell types in the brain. Both approaches may be valuable, and some large tissue repositories are available to conduct these studies. However, given the limited resources available, it may be necessary to choose one over another, said Potter. Andrew Miller argued that both approaches are necessary because picking a set of biomarkers now based on the limited data available could be dangerous. He advocated for more hypothesis testing with a discovery-based analytic strategy. Hyman said the correct approach may differ depending on the disease.

In terms of differences between therapeutic and scientific biomarkers, Miller also challenged workshop participants to think differently about functional disorders that fall into the realm of psychiatry and formal neurological disorders where there is clear pathology in the brain. For neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression, there may be relatively simple solutions available today to identify inflammation, and these may be proxies for what is going on in the brain. For example, it is now widely accepted that a systemic biomarker of neuroinflammation, C-reactive protein, can be used to predict response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, so subgrouping patients and assessing their responses to different treatment paradigms could accelerate treatment development, even as research continues to try to understand the cell-mediated immune processes that also contribute to neuroinflammation, he said.

Another major concern raised by Samad is how to manage the data already collected, including data that already exist within pharmaceutical companies. Hyman agreed, noting that underlying all of the challenges mentioned the need to better understand human biology. The appropriate specimens are precious and rare, he said, thus demanding a consortial process that can centralize the data production and analysis. Such a process was used successfully in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), for example, when investigators from multiple stakeholder groups and disciplines got together and laid out very clear questions, said Potter. This allowed the ADNI investigators to decide whether or not the measures were informative enough to answer those questions. While laying out the questions may be possible in the area of neuroinflammation, Potter wondered whether the techniques currently available to study brain microglia and astrocytes are adequate.

Beth Stevens suggested that these problems can all be addressed by bringing together the right consortia or group of people to do this work collaboratively by coming at problems from different perspectives and with different types of expertise. In addition, Bar-Or challenged the at-

tendees to think about ways of bringing together and mandating certain kinds of cohesion so that the same question can be asked identically across different samples collected from different diseases.

CONSORTIAL EFFORTS TO IDENTIFY AND VALIDATE BIOMARKERS OF NEUROINFLAMMATION

Campbell advocated for the use of precompetitive, public‒private consortia to facilitate the development of inflammation biomarkers, noting that multiple organizations with areas of common interest may be able to pool the necessary resources for well-powered studies that most likely will incur enormous costs and take years to complete. Such consortia will bring value to the entire field by promoting greater visibility, increasing the power of studies by enabling the enrollment of large numbers of participants, aggregating financial resources as well as the human resources of people with different skill sets, and reducing the risk of investment for individual partners, said Campbell. Eliezer Masliah noted that for several years the National Institute on Aging has been funding studies on CSF and fluid biomarkers conducted by public‒private consortia.

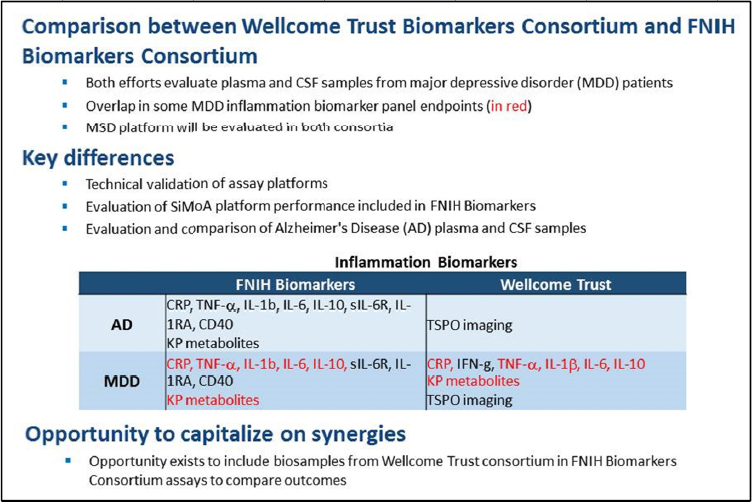

Within the area of neuroinflammation, two consortia that have been established in recent years were discussed in Chapter 6. Campbell described one of these, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium’s project, which will focus on blood and CSF biomarkers (thus, both peripheral and central immune responses) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and major depressive disorder (MDD). This project was established to develop biosignatures of neuroinflammation in CNS disorders, ultimately narrowing down their scope to one neurodegenerative disease, AD, and one psychiatric disorder, MDD, said Campbell. He described the two different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay platforms and a mass spectrometry platform that will be used to measure the selected neuroinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. He also outlined their three aims: (1) to validate the selected assay platforms with respect to sensitivity, linear range, reproducibility, and other parameters; (2) to develop inflammatory biosignatures based on a training set of samples; and (3) to confirm these biosignatures in a validation cohort of patients.

The other is the Wellcome Trust Consortium for Neuroimmunology of Mood Disorders and Alzheimer’s Disease. Bullmore said that in 2014

the Medical Research Council in the United Kingdom agreed to fund this consortium to focus on immunologic approaches to treat neuropsychiatric disorders, bringing together several academic centers in the United Kingdom with two pharmaceutical partners, GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen. The goal of this consortium was to build confidence in the concept of using immunotherapeutics in psychiatry by reanalyzing existing data from clinical trials and microarray datasets, as well as by conducting some novel experimental work, said Bullmore. He described the overall program, which includes the preclinical testing of new molecules contributed by the pharma partners as well as biomarker discovery in clinical studies aimed at exploring whether biomarkers can demonstrate a relationship between peripheral and central inflammation as well as a possible relationship between therapeutic resistance to antidepressants and peripheral inflammation. Ultimately, he said the consortium hopes to take one of the new molecules tested preclinically into an experimental medicine or proof-of-concept study for treatment-resistant depression. He added that in 2015 the consortium was expanded to include a wider range of activities in mood disorders and AD with funding from the Wellcome Trust and the addition of two more pharmaceutical partners, Lundbeck and Pfizer.

Campbell highlighted the opportunities for synergy between the efforts of the FNIH Biomarkers Consortium and the Wellcome Trust Initiative (see Figure 7-1). He said, for example, that it may be possible to include samples from the Wellcome Trust in the Biomarkers Consortium’s assay evaluation to provide a stronger synergized dataset. The Wellcome Trust has selected an overlapping set of fluid-based inflammatory biomarkers to assess in MDD patients. They are also including TSPO (translocator protein) imaging as an inflammation biomarker, whereas the FNIH Biomarkers Consortium has prioritized its work to the assessment of fluid biomarkers. Campbell said that cell-based measurements in the periphery and CSF could be incorporated in the future if the scientific evidence points in that direction and if additional funds are procured.

Beyond these existing consortia, Hyman proposed another large consortium to conduct transcriptomic studies in normal individuals as well as those with selected diseases, looking at cells and CSF, and sharing data about candidate biomarkers. Potter agreed, noting that it would be necessary to determine what questions to ask that would be informative, and whether adequate techniques are available to address those questions.

SOURCE: Presentation by Campbell, March 21, 2017.