2

Treatment of Obesity and Overweight in Adults

Health care providers encourage patients with obesity to lose weight to prevent or ameliorate obesity-related diseases and conditions and to improve the way they feel and function, said Susan Yanovski, co-director of the Office of Obesity Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health. She explained that they use three general modalities to help patients lose weight and maintain weight loss: lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery. Drawing on guidelines from professional societies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and large randomized controlled trials and observational studies, she summarized what is known about the efficacy of each of these

modalities in adults (in terms of weight outcomes) to lay the foundation for subsequent discussions at the workshop.

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS

Yanovski began by citing a 2013 evidence-based guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society (AHA/ACC/TOS) that addresses the efficacy of lifestyle interventions (based on randomized controlled trials). It states that patients who need to lose weight should receive a comprehensive intervention lasting at least 6 months that encompasses diet, physical activity, and other behavior modification (Jensen et al., 2014). The gold standard, Yanovski observed, is an on-site, high-intensity (at least 14 sessions in 6 months), and comprehensive intervention that can be delivered in group or individual sessions by a trained interventionist1 and persists for 1 year or more. With such an intervention, the mean weight loss seen is 5–10 percent of initial weight.2Jensen and colleagues (2014) describe a high standard of evidence for this guideline.

Based on a high standard of evidence,3 low- to moderate-intensity interventions delivered in primary care have not been shown to be effective, according to Yanovski. She added that other approaches, such as Web-based interventions, are considered secondary because they produce less weight loss, and thus fewer health benefits, with studies showing weight loss of up to 5 kilograms at 6–12 months (moderate standard of evidence).

Behavioral Treatment

Yanovski cited the definition for behavioral treatment of Foster and colleagues (2005, p. 230S) as “an approach used to help individuals develop a set of skills to achieve a healthier weight. It is more than helping people to decide what to change; it is helping them identify how to change.” She explained that components of behavioral treatment include self-monitoring of food intake, physical activity, and other behaviors; stimulus control, such as keeping unhealthy foods out of the house or making fruits and vegetables more available; goal setting, which may encompass not only weight goals

___________________

1 In responding subsequently to a question, Yanovski asserted that the training is what is important, and it does not need to be delivered by a physician or other health professional.

2 “Sustained weight loss of 3%-5% produces clinically meaningful health benefits, and greater weight losses produce greater benefits” (Jensen et al., 2014).

3 The definitions for “low,” “medium,” and “high” standards of evidence are described in the 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults.

but also behavioral goals; problem solving, such as how to handle an upcoming vacation meal; stress reduction; and relapse prevention, which is critically important, Yanovski said, because “losing weight is the easy part compared to keeping it off.”

Defining the Efficacy of Weight Management Interventions

Yanovski continued by reporting that, according to guidance from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the development of weight management products, a product can be considered effective for weight management if after 1 year of treatment either of the following occurs: (1) the difference in mean weight loss between the groups treated with the active product and placebo is at least 5 percent, and the difference is statistically significant; or (2) the proportion of subjects who lose 5 percent or more of baseline body weight in the active-product group is at least 35 percent and approximately double the proportion in the placebo-treated group, and the difference between groups is statistically significant. According to Yanovski, the second criterion reflects the fact that some people respond to any given treatment and some do not, and the reason for the 5 percent difference is that this amount of weight loss generally is regarded as clinically meaningful in terms of improving health and reducing comorbidities (FDA, 2007). By this standard, she said, “if behavioral treatment were a drug, it would be approvable” by FDA.

Look AHEAD: Action for Health in Diabetes Study

Yanovski described the Look AHEAD: Action for Health in Diabetes study, an example of an intensive lifestyle intervention using behavior modification strategies. In this multicenter randomized controlled trial, more than 5,000 participants with both type 2 diabetes and overweight or obesity were assigned to receive either an intensive lifestyle intervention or diabetes support and education (the control). The participants were followed for up to 11 years, and although the primary outcome of interest was cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, weight also was monitored. The intensive lifestyle intervention included diet, physical activity, and behavioral strategies delivered in group and individual sessions weekly for 6 months, and then three times a month for the next 6 months. Yanovski noted that this intervention met the gold standard approach to treating obesity with behavioral modification. (In response to a question, she reported that a relatively small proportion of individuals [~20 percent] may respond to low-intensity primary care interventions [e.g., advice from a physician on diet and physical activity], but the efficacy of such approaches is relatively low.)

Furthermore, Yanovski continued, at 1 year the patients receiving the intensive lifestyle intervention had lost on average more than 8 percent of

their initial body weight versus 0.6 percent in the control group. Almost 70 percent of the former patients had lost 5 percent or more of their initial body weight, compared with about 14 percent in the control group (Look AHEAD Research Group, 2007). Furthermore, almost 40 percent of the intervention group—about 10 times as many as in the control group—had lost more than 10 percent of their initial weight.

With even the best weight loss treatment, Yanovski stated, results tend to diminish over time. Even after 8 years, however, the group receiving the intensive lifestyle intervention had a greater percentage reduction in body weight—4.7 percent—compared with the control group—2.1 percent (Look AHEAD Research Group, 2014).

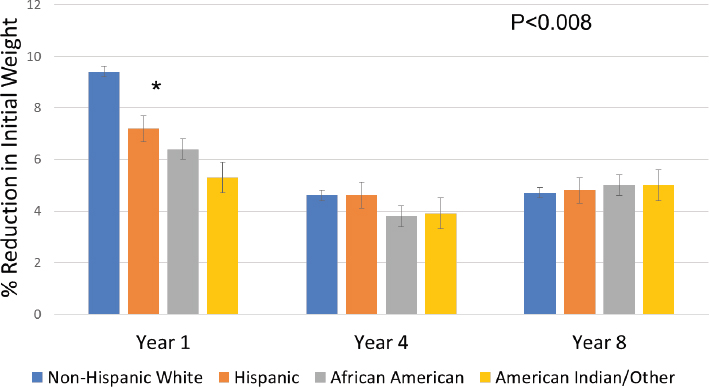

Yanovski observed further that the data from this study also shed light on disparities in weight loss in racial and ethnic minority populations. More than 35 percent of the study’s participants were members of racial and ethnic minorities, including about 16 percent African Americans, 13 percent Hispanics, and 5 percent American Indians. In the first year, non-Hispanic whites in the intensive lifestyle intervention arm of the study lost more weight than their African American, Hispanic, or American Indian counterparts (see Figure 2-1). At years 4 and 8, however, weight loss among these four groups was about the same. “There may be less weight loss initially,” observed Yanovski, “but perhaps slower regain.”

The results from this study are encouraging, Yanovski asserted, but

SOURCES: Presented by Susan Yanovski on April 6, 2017 (data from Look AHEAD Research Group, 2014). Reprinted with permission.

many challenges remain. Even with the intensive lifestyle intervention, she noted, 30 percent of participants did not lose 5 percent or more of their initial weight. How can these nonresponders lose sufficient weight to improve health?, she asked, and how can longer-term weight loss be maintained and the regaining of weight minimized?

PHARMACOTHERAPY

One answer to these questions, Yanovski argued, embodied in a number of professional society guidelines, is that pharmacotherapy can be used as an adjunct to lifestyle interventions involving behavioral modifications. She noted that FDA has approved nine drugs for weight management treatment for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more, or 27 or more if they have associated comorbidities (see Table 2-1). Four of these drugs—benzphetamine, phendimetrazine, diethylpropion, and phentermine—were approved in 1973 or earlier. All were approved only for short-term use, as a way to jump-start weight loss. Yet all remain on the market, Yanovski said, and are frequently prescribed off-label for periods longer than 12 weeks, which is the generally accepted definition of short-term. In fact, she pointed out, phentermine is by far the most prescribed weight loss drug despite being approved only for short-term use.

TABLE 2-1 Drugs Approved by the Food and Drug Administration for Obesity Treatment

| Generic Name | Trade Names | DEA Schedule | Approved Use | Year Approved | Price per Month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzphetamine | Didrex | III | Short term | 1960 | $20–$50 |

| Phendimetrazine | Bontril, Prelu-2 | III | Short term | 1961 | $6–$20 |

| Diethylpropion | Tenuate | IV | Short term | 1973 | $47–$120 |

| Phentermine | Adipex, Ionamin | IV | Short term | 1973 | $6–$45 |

| Orlistat | Xenical, Alli | None | Long term | 1999 | $45–$520 |

| Lorcaserin | Belviq | IV | Long term | 2012 | $240 |

| Phentermine + Topiramate-ER | Qsymia | IV | Long term | 2012 | $140–$195 |

| Bupropion-ER + Naltrexone ER | Contrave | None | Long term | 2014 | $180–$210 |

| Liraglutide | Saxenda | None | Long term | 2014 | $900–$1,000 |

NOTE: ER = extended release.

SOURCE: Presented by Susan Yanovski on April 6, 2017. Reprinted with permission.

Five drugs, Yanovski continued, have been approved for longer-term use—orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine-topiramate extended release (ER), bupropion-naltrexone ER, and liraglutide. Orlistat is a gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor that inhibits the absorption of about one-third of dietary fat; it has been on the market since 1999 and in a lower-dose formulation is the only approved over-the-counter approved weight loss medication. Lorcaserin is a selective serotonin receptor agonist. The two combination drugs combine drugs previously approved as monotherapies: phentermine-topiramate ER combines a short-term weight loss medication (phentermine) with an antiseizure and antimigraine medication (topiramate), while bupropion-naltrexone ER combines an antidepressant and smoking cessation drug (bupropion) with a medication for opioid dependence and alcohol abuse (naltrexone). Liraglutide, the most recent long-term therapy to be approved, is a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist. At a higher dose, the drug is approved for obesity treatment, and at a lower dose for diabetes treatment. It is the only one of the medications that is injectable. Yanovski added that the two oldest drugs—lorcaserin and phentermine-topiramate ER—are Drug Enforcement Administration Schedule IV drugs because they have at least some potential for abuse. Orlistat, the bupropion-naltrexone combination, and liraglutide are not controlled.

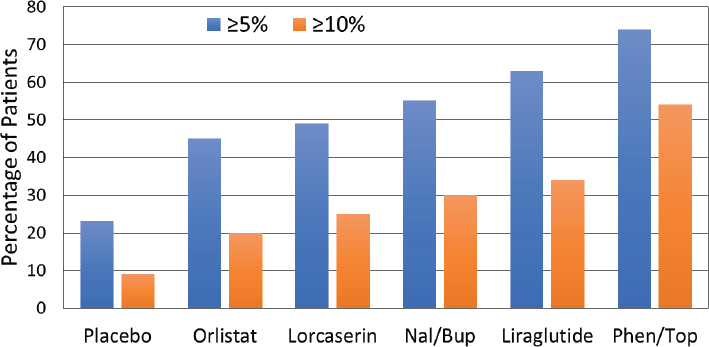

With the obesity medications approved for long-term use, Yanovski and Yanovski (2014, 2015) found that after 1 year, the placebo-subtracted weight loss ranged from about 3 percent for orlistat and lorcaserin to more than 9 percent for phentermine-topiramate, with intermediate weight loss for liraglutide and bupropion-naltrexone. The proportion of patients achieving a weight loss greater than 5 percent and 10 percent at 1 year showed a similar pattern (see Figure 2-2) (data from Khera et al., 2016). Interestingly, Yanovski observed, multiple studies have shown that weight loss at 12 weeks predicts the response at 1 year. For example, depending on the medication used and the intensity of the lifestyle intervention, between 25 percent and more than 50 percent of treated patients may not achieve a 5 percent reduction after 12 weeks of therapy, which means they are exposed to the risks and costs of a drug but have little prospect of benefits. In that case, Yanovski said, guidelines call for consideration of discontinuing the drug and reevaluating treatment options, including the intensification of behavioral strategies, referral to a dietician or lifestyle interventionist, a medication with a different mechanism of action, reassessment and management of medical or other contributory factors, and referral for bariatric surgery in appropriate patients.

In response to a subsequent question, Yanovski replied that a risk-benefit analysis is necessary for any medicine. Each medication, she observed, has its own side effects (although, as she noted, obesity also has side effects). “For example,” she said, “phentermine can raise pulse and blood

NOTE: Nal/Bup = naltrexone-bupropion; Phen/Top = phentermine-topiramate.

SOURCES: Presented by Susan Yanovski on April 6, 2017 (data from Khera et al., 2016). Reprinted with permission.

pressure. Lorcaserin can’t be used with SSRI [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor] antidepressant medications. Topiramate and phentermine during pregnancy can cause an increased risk of cleft lip and palate in offspring. This is a very individualized process. That is why patients need to go to their physician, who knows their medical history and what other medications they are taking.”

BARIATRIC SURGERY

Yanovski described three bariatric surgical procedures used commonly in the United States. The first was the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, which usually is described as a restrictive and malabsorptive procedure, but is also known to have significant metabolic effects on bile acids, gut hormones, and the microbiome. Of the three procedures, Yanovski noted, the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass generally shows the greatest improvement in medical comorbidities.

The second procedure Yanovski described was the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, an inflatable silicone device placed around the top portion of the stomach that slows and limits food consumption. She explained that it results in less weight loss compared with the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, but the procedure is reversible.

Finally, Yanovski described the sleeve gastrectomy, sometimes called the gastric sleeve, which also is restrictive because it excises 80 percent of the stomach, and additionally appears to have metabolic effects similar to those of a gastric bypass. This procedure is increasing dramatically in popularity, Yanovski stated, rising from 18 percent of bariatric surgical procedures in 2011 to more than 50 percent in 2016. “It is now the most commonly performed procedure,” she noted, “despite the fact that we have very little long-term data on it.”

The AHA/ACC/TOS evidence-based guideline addresses the benefits and risks of bariatric surgery procedures, Yanovski continued. Jensen and colleagues (2014) suggest that physicians advise their patients with a BMI of 35 or higher and a comorbidity or a BMI of more than 40 that bariatric surgery may be an appropriate option for improving health and offer a referral to an experienced bariatric surgeon for consultation and evaluation (Jensen et al., 2014). According to the guideline, Yanovski reported, depending on the procedure undertaken, mean weight losses in 2–3 years can be 20–35 percent of initial weight (with a high standard of evidence). Some regain of weight is seen, she noted, amounting to about 7 percent of initial weight over 10 years. However, she added, the standard of evidence for this last observation is low, partly because it relies on different procedures than what are common today.

Yanovski stated that in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS)—an observational cohort study of adults who underwent their first bariatric surgery at 10 U.S. hospitals between 2006 and 2009 and 70 percent of whom underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 25 percent gastric band, and 5 percent other—those who underwent the gastric bypass procedure had lost more than 30 percent of their initial weight at 1 year and maintained a fair amount of that weight loss on average at 3 years (Courcoulas et al., 2013). People who underwent laparoscopic gastric banding lost significantly less weight, about 16 percent of initial weight at 3 years, which Yanovski noted is consistent with results of other studies.

Yanovski pointed out that patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery tended to lose about the same amount of their initial weight in the first half year after surgery—around 25 percent. After that, she said, groups of patients tended to follow discrete trajectories. She reported that about 2 percent started to regain weight almost immediately, averaging about a 10 percent weight loss after 3 years. Another relatively small group, about 6 percent, continued to lose weight for up to 2 years, at which point they were down to almost half of their initial weight, and at 3 years they still averaged about a 45 percent loss. Other groups had intermediate trajectories, with weight losses averaging 20–40 percent after 3 years.

Results for laparoscopic gastric banding were more variable, Yanovski

continued. About 20 percent of the cohort started to regain their weight and were down 5 percent or less of their initial weight by 3 years. Another small group, about 4 percent, lost almost as much weight as those who underwent gastric bypass, with other groups following intermediate trajectories. Also, Yanovski added, comparisons of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass found that the former produces slightly less weight loss than the latter (Schauer et al., 2017).

Courcoulas and colleagues (2014) looked at more than 100 preoperative and operative variables as predictors of weight and health outcomes in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. “Unfortunately,” said Yanovski, “we found that few baseline variables were associated with 3-year weight change, and the effects were small. These results indicate that baseline variables have limited predictive value for an individual’s chance of a successful weight loss outcome after bariatric surgery.”

KNOWLEDGE GAPS

Yanovski concluded by listing some of the knowledge gaps with respect to the efficacy of obesity treatment in adults:

- the efficacy of drug and surgical treatments in racial and ethnic minority groups and other populations subject to health disparities, such as rural populations and those of low socioeconomic status;

- the effectiveness of newer modes of delivery for lifestyle intervention (such as Web-based and telephonically delivered interventions) in large and diverse populations;

- predictors of response beyond initial weight loss for all obesity treatments, encompassing genetic and phenotypic characteristics (including behavioral and metabolic characteristics) that could allow more targeted treatment recommendations; and

- the long-term safety and efficacy of sleeve gastrectomy and other newer procedures and devices for obesity treatment.

This page intentionally left blank.