7

Workforce and Training

As roundtable consultant Bill Dietz, moderator of the panel on workforce and training, pointed out, the development of the workforce is critical given how many millions of patients with obesity in the United States are underserved. He calculated that there are about 90 adults with severe obesity for every adult practitioner, and about 50 children with severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥120 percent of the 95th percentile) for every pediatric practitioner. The three speakers on this panel examined both

the competencies expected of the workforce and ways of developing and sustaining those competencies.

OBESITY CARE COMPETENCIES

According to Goutham Rao, Jack H. Medalle professor and chairman of family medicine and community health at University Hospitals of Cleveland and the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, a range of organizations—from the Academy for Eating Disorders to the YMCA—have been involved in a collaborative effort to develop core competencies that obesity care providers should have. He described 10 of these draft competencies as examples of the skills and knowledge expected of the obesity care workforce.

Rao explained that the first core competency is that providers should be able to demonstrate a working knowledge of obesity as a medical condition,1 including, for example, key measures and their limitations for the assessment of obesity and its comorbidities. He explained that BMI is by far the most common anthropometric measure used to identify obesity. However, he argued, the threshold used in the United States to distinguish between overweight and obesity—a BMI of 30—does not necessarily apply to all populations, such as Asians, for whom lower thresholds generally are accepted. “If you have an interest in obesity, this is something you should know,” he asserted.

The second core competency, Rao continued, is that providers should be able to demonstrate a working knowledge of the epidemiology and key drivers of the obesity epidemic, including the social, cultural, and other factors that have contributed to the epidemic. These drivers are wide ranging, he acknowledged, but members of the workforce should have an understanding of these factors “whether you are in dietetics, nutrition, or any field within medicine.”

The third core competency, Rao said, is that providers should be able to describe the disparate burden of obesity for different populations and approaches to mitigating those inequities. For example, he elaborated, they should be able to explain the role of inequities associated with and determinants of obesity and its outcomes. “It is not enough to know that there are disparities in the prevalence of obesity,” he asserted. “You need to go one step further to explore what might be some potential causes.” As one potential cause, he pointed out that 31 percent of whites live in com-

___________________

1 The Provider Competencies for the Prevention and Management of Obesity was published on June 7, 2017. See https://bipartisanpolicy.org/library/provider-competencies-for-the-prevention-and-management-of-obesity (accesssed November 14, 2017). The first competency now reads, “Demonstrate a working knowledge of obesity as a disease.”

munities with one or more supermarkets, compared with only 8 percent of blacks. “Having knowledge of that type of information is the essence of this particular competency,” he said.

Rao explained that the fourth core competency involves interprofessional obesity care, specifically being able to describe the benefits of working interprofessionally to treat obesity in ways that cannot be achieved by a single health professional. For example, he said, providers should be able to summarize the value of and rationale for including the skills of diverse interprofessional teams in treating obesity. As clinical director of the Weight Management and Wellness Center at Children’s Hospital Pittsburgh for 7 years, “I could not have succeeded without the help of dieticians, psychologists, nursing professionals, et cetera. Even within that confined clinical environment, interprofessional care is critically important.”

The fifth core competency involves the integration of clinical and community care for the prevention and treatment of obesity. Rao elaborated by explaining that providers should be able to apply the skills necessary for effective interprofessional collaboration and integration of clinical and community care for obesity. As an example of how to perform effectively in an interprofessional team, he envisioned a provider calling a weight management professional and saying, “I would like to let you know that I raised Mr. Webb’s insulin dose because his diabetes was not well controlled. Please let me know if you plan to make any changes to his dietary plan.” He added, “that could happen within my hospital setting, but it is not yet the normal practice.”

The sixth core competency involves discussions and language related to obesity, Rao continued. The language related to obesity is critical, he noted, such as using the word overweight rather than fat. Providers should use patient-centered communication when working with individuals with obesity and others, Rao said, and discuss obesity in a nonjudgmental manner using person-first language in all communications. One approach, he noted, is to ask for permission: “I am concerned about your weight and its impact upon your health. Would it be okay if we discussed this?” Another is to use an open-door approach: “I want to let you know that I am concerned because your daughter’s BMI percentile is 98.” When a patient asks what that means, the provider immediately follows up with, “It means she is at a higher weight than the majority of girls her age. This puts her at risk for problems such as diabetes and high blood pressure. Is this something that concerns you as well? Is this something you would like to work on together?” According to Rao, “It is a very gentle approach. It expresses concern. It uses respectful language.”

The seventh core competency is to recognize and mitigate weight bias and stigma. Rao related the story of Gina Score, who was a 14-year-old girl in 1999 when she attended a boot camp in South Dakota. She was about

5’4” tall and weighed 226 pounds. Sent on a forced run on a very hot day for about 3 miles, she quickly fell behind the other girls, and no one looked back to see how she was doing. On the way back from the run, the counselors and the other girls found her face down on the ground, about halfway up the trail. Rao explained that “nobody called 911. She was foaming at the mouth. Finally, somebody did something. She died a few hours later. I always point out that . . . had she been a slender girl, or had she been of a different ethnicity or a different background, I think somebody would have done something. She faced the ultimate humiliation and, of course, the ultimate consequence.” Rao emphasized that providers need to minimize bias toward people with obesity and recognize and mitigate the biases of others. For example, he said, while a slender patient coping with knee arthritis might be given a steroid injection, a very similar patient with obesity might be told simply to lose weight, even though the same treatment could have benefited her.

The eighth core competency involves accommodating people with obesity. As described by Rao, this competency means providers should implement a range of accommodations and safety measures specific to people with obesity. “Privacy and respectfulness are critically important,” he said. For example, he noted, scales connected to health care professionals by Wi-Fi are increasingly popular because of the privacy they provide.

The ninth core competency is providing evidence-based care and services for people with or at risk for obesity. Rao stated that BMI and other anthropometric measures, such as waist circumference, should be evaluated routinely, and evidence-based individual and family behavioral change strategies such as motivational interviewing and behavioral therapy should be employed. An example is to replace the statement “It’s pretty simple—get to the grocery store once a week and give up fast food” with “You find it hard to make the time to shop and cook meals and find fast food a lot more convenient.” As Rao pointed out, “I guarantee you will get a better response from the patient and more engagement as you go forward.”

The final core competency involves special concerns, such as providing evidence-based care and services for persons with comorbidities. Rao cited the example of an eighth grader who is sent to the school nurse’s office after striking her head on the edge of her desk and suffering a small bruise. Upon questioning, she says that she hit her head when she inadvertently fell asleep in class and that this happens quite often. She tells the nurse that her younger brother, with whom she shares a room, always complains that she snores. The school nurse, having some knowledge in this area, suspects obstructive sleep apnea and speaks to the girl’s parents, who in turn seek appropriate evaluation and care. “That is the basic level that we would expect from people who are concerned about this issue,” said Rao.

EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL OBESITY INITIATIVES

Educational and professional obesity initiatives, such as those focused on developing the competencies described by Rao, need to be both top-down and bottom-up, asserted Robert Kushner, professor of medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, and director, Center for Lifestyle Medicine at Northwestern Medicine. This means, he elaborated, that the initiative should encompass both clinicians who are already in practice and trainees. In the former case, he explained, important goals are to create a subspecialty or focused practice and provide continuing medical education; in the latter case, important goals are to develop educational domain competencies and entrustable professional activities related to obesity and to include obesity-related items on the step exams of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE). Furthermore, he argued, it is important to pursue these goals in parallel so that competencies developed during a student’s education do not fade when the student begins to practice. “We have to think in terms of all those levels all at once,” he suggested.

Kushner began by looking at the exams medical students and residents must take to advance in their careers. “People do learn by what is on the test,” he observed, which means that the USMLE is critical in shaping students’ ability to apply knowledge, concepts, and principles and demonstrate fundamental patient-centered skills that constitute the basis of safe and effective patient care. He and five colleagues reviewed a list of items that included obesity-related keywords—such as obesity, obese, body mass index, and weight loss—that had been selected by content experts and identified by the staff of the National Board of Medical Examiners. Using a rubric developed by the American Board of Obesity Medicine, which divided items into four domains and 107 possible subdomains, they determined that only 36 percent of the items with obesity keywords were judged to be directly related to obesity (Kushner et al., 2017a). Of those items, Kushner said, the vast majority pertained to the diagnosis and management of obesity-related comorbidities—such as type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, metabolic syndrome, and polycystic ovarian syndrome—rather than obesity. He added that most of the obesity-coded items were found in four organ system categories—cardiovascular, endocrinology, female reproduction, and respiratory—and that 80 percent of the coverage of obesity-coded items was limited to six subdomains. The current concepts of obesity prevention and treatment, including basic science, assessment, and management, were not addressed.

According to Kushner, the group’s key recommendation was that items be added to the exams to cover the following topics: basic science of obesity; socioeconomic and behavioral determinants of obesity; assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of obesity per se; behavioral medicine; obesity

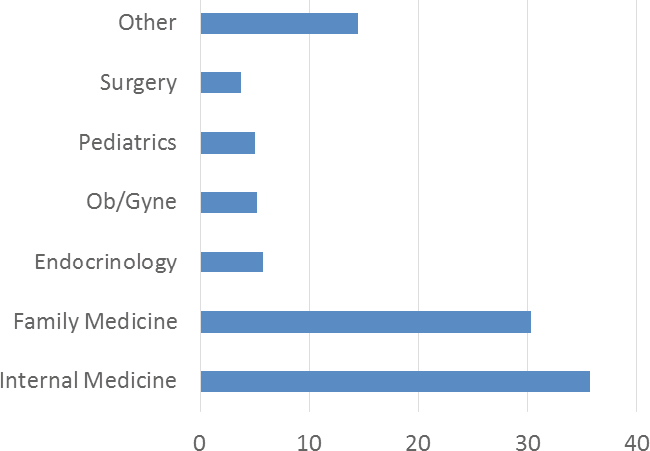

NOTE: Ob/Gyne = obstetrics and gynecology.

SOURCE: Presented by Robert Kushner on April 6, 2017. Reprinted with permission.

pharmacotherapy; bariatric surgery; and weight bias and discrimination. The group also encouraged the exam developers to use people-first language, such as “a patient with obesity” rather than “an obese patient.” Lastly, it recommended that obesity content experts be assigned to the USMLE item-writing committees. “To their credit,” reported Kushner, “they asked me, and I am now serving on the chronic care committee of this examination in writing 40 items per year to enrich the pool. I will be, hopefully, among many who will be doing that.”

Kushner also discussed the American Board of Obesity Medicine’s rationale for developing an obesity medicine physician pathway. Certification brings increased recognition and competency to the field, he observed, and lays a foundation for improved reimbursement. He noted that anticipated advances in obesity care over the next decade in the areas of pharmacotherapy, surgical procedures, and devices will require specialty training and expertise. In addition, he suggested, certified physicians can serve as clinical and educational champions at the local and national levels. He noted that board certification would establish standards of appropriate knowledge and professional practice in obesity medicine.

Kushner reported that between 2012 and 2016, the number of obesity physician diplomats grew from 587 to 2,068, with primary care clinicians most often being certified (Kushner et al., 2017b) (see Figure 7-1). It is a relatively new specialty, he said, but he asserted that these are the kinds of trends that will develop the workforce.

INTERDISCIPLINARY SPECIALIST CERTIFICATION IN OBESITY AND WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

According to Linda Gigliotti, consultant with the Diocese of Orange (California) as director of wellness programs, the new Interdisciplinary Specialist Certification in Obesity and Weight Management was developed to confront the full complexity of obesity. As it became clear that dietary manipulation could not fully address the problem, she explained, dietitians sought additional training to become more skilled in working with clients who have obesity. In the early 2000s, the Commission on Dietetic Registration began providing certificate-of-training programs for adult management, followed by a special training program on childhood and adolescent weight management. An advanced level in adult weight management was added in 2010. “These are very intensive training programs,” said Gigliotti, that include prereading, 2.5 days of live presentations, and a one-time opportunity for a posttest to secure a certificate. Between 35 and 50 hours of continuing education are offered for completing the certificate, which she noted has been extremely popular with dietitians, more than 20,000 of whom have completed the courses. Up to six different certificate training sessions continue to be offered each calendar year.

Gigliotti observed, however, that many people attending these certificate programs have expressed the desire for a credential that reflects additional expertise and lends credibility to dietitians who are working with people with obesity. At the same time, she noted, other disciplines in health care have recognized the same need, as demonstrated by the medicine credential offered by the American Board of Obesity Medicine and a credential for bariatric nurses developed by the American Society of Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery.

In early 2013, Gigliotti continued, the Commission on Dietetic Registration, the credentialing agency for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), took the lead in developing a new credential. Before work began on the credential, however, several groups within the AND expressed interest in developing an interdisciplinary credential. Such a credential, Gigliotti explained, could reflect the fact that obesity is a multifactorial, chronic disease requiring interdisciplinary intervention. After some consideration and study, a decision was made to move forward with developing the interdisciplinary Certified Specialist in Obesity and Weight Management (CSOWM) credential.

Gigliotti reported that an Interdisciplinary CSOWM Practice Analysis Task Force reviewed the licensure and certification requirements of several allied health professional groups to determine the degree to which they were involved in weight management and obesity treatment, as well as their interest in pursuing a specialist certification in this area. Their recommenda-

tion, she said, was to include the following professions in the certification: registered dietitian nutritionists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, clinical exercise physiologists, licensed behavioral clinical psychologists or therapists, and licensed clinical social workers. She explained that work is ongoing to develop the certification exam and repeat a practice analysis, in part to consider other professions. In response to a question, she noted that the Commission on Dietetic Registration also is working to get the word out about the new certification. “This is definitely a work in progress,” she said.

MAKING ROOM FOR WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

One issue discussed in the question-and-answer period was how to make room for obesity training in a medical education curriculum that is already crowded with subjects. Rao pointed out that subjects that used to be part of the medical curriculum have been removed as priorities have shifted. “As things become more important from a public health standpoint,” he said, “they will start to enter into the curriculum.” In addition, he observed, an initiative among a small group of schools can spread significantly when it addresses a need in medical education and practice.

Kushner pointed to the importance of having a local champion who can advocate for a subject and integrate that subject into instruction in multiple ways. “For example,” he said, “most of our obesity is in the endocrine module, but my colleagues and I are ensuring that obesity is also part of the cardiovascular module, part of the pulmonary module, and everything else. . . . You have to walk the walk and actually push it forward.” This can happen not only at large medical schools but elsewhere as well, Rao added. As an example he cited Project Echo, which started in New Mexico with the goal of training primary care physicians to manage complex medical problems. The prototype, he explained, was hepatitis C management, with the project showing that not just primary care physicians but also advanced care practitioners such as nurse practitioners could provide care for these patients as well as could the specialists at Albuquerque. He noted that the success of this program has provided impetus for expanding it to other areas, including childhood obesity. “Training primary care physicians and other providers to provide care is the way to go in tackling this problem,” he asserted, “rather than keeping everything within the ivory tower, which is what has been taking place so far.”

Kushner also mentioned another competency initiative, an intersociety Obesity Medical Education Collaborative, which has developed competencies, benchmarks, and entrustable professional activities for obesity care. “We are trying to make this camera ready for the schools,” he explained, “so that if they want in-patient care or knowledge- or system-based care,

they will have competencies with benchmarks already developed that they could use within their curriculum.” He added that if clinicians associated with the Obesity Medicine Association had academic affiliations, they, too, could have leverage to work with the education committee.

This page intentionally left blank.