5

Treating Severe Obesity in Adolescents and Children

A CASE STUDY

When Nikki Highfield’s son Ryan was in fifth grade, “he became different,” she said. “He started struggling in school. He was having social

issues. All of a sudden, he couldn’t do work that I thought he should be able to do.” The family went to a psychologist, and with her help, Ryan’s story came out. “He felt like the ‘fat’ kid,” recounted Highfield, who has been a parent advocate for the Healthy Weight Network. “He was tired of being slow, being the last one in baseball, being the last one in basketball.”

Through their psychologist, the family began working with the Healthworks program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. When they started the program, Highfield reported, Ryan weighed 144 pounds, had a body mass index (BMI) of 28, and was diagnosed with severe obesity. After meeting with the care team, including a nutritionist and an exercise physiologist, she “knew right away we had a lot of changes we had to make. We ate out a lot. Even when we ate at home, it was not healthy eating that we were doing.” Their dietician gave them a food chart featuring red, yellow, and green foods rather than the food pyramid. “We live by red, yellow, green foods now,” she said. “[They’re] easy to identify. We talk at home. If you can eat it out of the refrigerator, you are probably okay. Freezer maybe. If it comes off the shelf, it is probably not good for us to eat.”

Highfield and Ryan live with her parents, and she said that both she and her mother have suffered from weight issues. However, her belief is that “I don’t expect him to make the right decisions if I can’t make the right decisions. When we go out to eat, he and I typically share a meal. It is just what we do. We have learned that you probably don’t need the whole portion that is being served to you.”

Highfield’s family has also had heart issues, and Ryan’s cholesterol was 174 when they started at Healthworks, with an low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level of 109 and a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level of 50. When he last had his blood work done, his cholesterol was down to 130, with LDL and HDL levels of 55 and 62, respectively. “That’s attributed to his hard work and his exercising,” said Highfield. “He really works hard on it.”

Ryan’s dietician and exercise physiologist have been critical members of his care team, Highfield said. His dietician has given him ideas about how to deal with unhealthy food options or settings. Moreover, Highfield noted, “Healthworks is fortunate because we have one of the nation’s best culinary schools in our backyard at Cincinnati State. They offer cooking classes to these kids. Ryan has taken four or five of the cooking classes. . . . It has given him skills so that he can cook himself a [healthy] meal.”

Ryan also has found positive role models who have inspired him. At a YMCA camp, he became friends with an 18-year-old who had recently lost 100 pounds. “Scott was able to teach him how to exercise, give him hints, tell him what he should do,” Highfield said. He also met another 18-year-old who brought a packed lunch every day. By the sixth grade, Highfield explained, “he started on his own packing his lunch. He would pack turkey or ham roll-ups with a piece of lettuce. He would pack several different

fruits with him. He was drinking water instead of a Capri Sun. All those things started to change.”

The next year, in seventh grade, Ryan tried out for the basketball team—which Highfield characterized as “a step that we never thought he would make”—and made the A team. Then he made the freshman team in high school. “Now he is working toward next year,” said Highfield. “He is not the fastest kid. He was starting to go back on the upswing, not severely, but not the right way. He has found another role model and is on the right track again. He exercises at least 2 hours a day, 6 days a week, with his older cousin. They lift weights. They do cardio. His goal is to make the varsity team next year. Will he make it? Who knows? But the support is there for him to make it.”

Soon Ryan will graduate from high school, Highfield acknowledged, and go to college. “Dorm food is not always the best food,” she said. But the entire family is continuing to help Ryan develop the tools he will need to achieve his goals.

IDENTIFICATION, ASSESSMENT, AND TREATMENT OF SEVERE OBESITY IN CHILDREN

Identification of obesity in children typically has relied on growth charts, noted Susan Woolford, assistant professor and co-director of the Mobile Technology to Enhance Child Health Program, Child Health Evaluation and Research Unit, University of Michigan. Overweight has been defined as a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentiles, with obesity being above the 95th percentile. Severe obesity used to be defined as being above the 99th percentile, but this is not a statistically robust measure, Woolford asserted. It also creates a ceiling effect, she suggested, whereby even significant amounts of weight loss may not result in a change in categories.

Woolford referred to a recent proposal to use 120 percent of the 95th percentile for age and sex to define class 2 obesity for children, which corresponds to a BMI of about 35–40 in adults (Skinner and Skelton, 2014). A cutoff of 140 percent of the 95th percentile for sex and age would be classified as class 3 obesity, she explained, which would correspond to a BMI above 40 for adults. She argued that this system would provide “a much better ability to look at changes in a child’s weight over time.” She added that it also would provide better population measures. For example, she noted, while the prevalence of obesity overall in children may have plateaued over the past few years, class 2 and class 3 obesity has continued to increase, with notable disparities in African American and Hispanic children.

Woolford observed that children with obesity are likely to be at greater risk for many comorbidities, including pulmonary, gastrointestinal, renal,

musculoskeletal, neurologic, cardiovascular, endocrine, and psychosocial issues. Many of these are conditions seen in adults, she noted, but children are showing them at younger ages, meaning they must live with them longer. Also, she said, because children are still developing, they can experience such problems as orthopedic conditions (e.g., Blount’s disease and slipped capital femoral epiphysis) that adults do not have.

Woolford also emphasized the need to pay attention to possible psychosocial comorbidities, such as depression and poor self-esteem, even though the evidence that those with severe obesity have a higher prevalence of these psychosocial issues relative to those with class 1 obesity is inconclusive. Moreover, she acknowledged the potential role of genetics in early-onset severe obesity, adding that the MC4 receptor mutation is found in approximately 4 percent of such cases in children and adolescents (Reinehr et al., 2007).

Of the four stages of obesity treatment—prevention plus, structured care, multidisciplinary care, and tertiary care—severe obesity in children generally warrants stage three and four care, Woolford asserted. She explained that multidisciplinary teams typically consist of exercise specialists, psychologists/behavioral specialists, social workers, dieticians, and physicians (Wilfley et al., 2017). Among the activities and tools used by such teams are behavioral modification, food monitoring, group exercise, goal setting, contingency management, token economy, and take-home tasks. Parental participation is vital, stressed Woolford, across the spectrum of ages, and at least 26 contact hours are needed, with 52 being even better. She added that children also need to be evaluated in a systematic way over time.

Woolford continued by emphasizing that such programs need to have an appropriate theoretical basis. To illustrate, she cited self-determination theory, which promotes the progression from amotivation (“I’m just not exercising.”), to external regulation (“I’ll do it because my mother will give me a reward.”), to introjected regulation (“I know I should do it and feel ashamed if I don’t.”), to identified regulation (“I’ll do it because it is important to me.”), to integrated regulation (“I’ll do it because it is integrated with my values.”), to intrinsic motivation (“I’ll do it because I enjoy it and it is pleasurable.”). Motivational interviewing can help move people along this continuum, she explained. For example, a recent randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing and dietary counseling for treatment of obesity in primary care produced a statistically greater decrease in mean BMI compared with a control group receiving usual care (Resnicow et al., 2015).

If stage three programs are not as effective as needed, Woolford continued, patients may consider stage four approaches. As an example, she cited a liquid diet, although in pediatrics these diets have not been shown to be widely successful since many adolescents find it difficult to adhere to

them. With regard to medications, only one—orlistat, which is approved for ages 12 and above—has been approved for use in pediatrics. However, when adolescents hear that its unpleasant side effects can include flatulence, greasy stool, and fecal incontinence (Petkar and Wright, 2013), most “are not rushing to sign up,” said Woolford.

Many children do not have the BMI level or comorbidities that warrant consideration of bariatric surgery, Woolford observed. Moreover, she added, they may not have the capacity to decide whether they want bariatric surgery; they may not be able to adhere to the changes required for receipt of the surgery; and they also may not be physiologically mature enough to have the surgery.

Given the lack of effective stage four options, Woolford continued, multidisciplinary programs remain the most likely approach. However, they too face many obstacles, she argued, including high costs, poor reimbursement, high attrition rates, low reach, poor adherence, and poor postprogram weight loss maintenance (Skelton and Beech, 2011). Nevertheless, she said, reasons for optimism also exist. For example, she noted, new medications are possible. Primary care could be better integrated with tertiary care, and better connections with the community could improve outcomes, as could new uses of technology with severe obesity. For example, Woolford elaborated, digital devices could be used to tailor treatment, bring in gamification, measure energy balance, conduct remote monitoring, and perhaps lower costs. She and her colleagues developed a text messaging app, for instance, that can identify where children are and send them a message when they are in an eating environment, telling them to consider a healthy alternative. “These types of interventions hopefully will help us move from a winter of despair to a springtime of hope in the treatment of childhood obesity,” she remarked.

BARIATRIC SURGERY

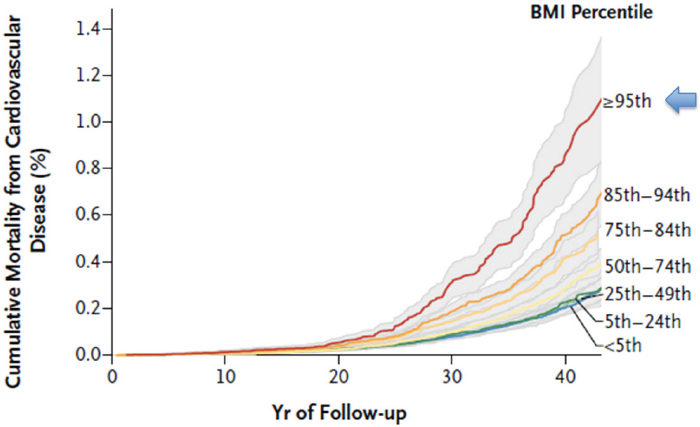

Although obesity has plateaued in some groups, that is not the case for adolescents, noted Marc Michalsky, professor of clinical surgery and pediatrics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine and Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Severe obesity has continued to rise among adolescents aged 12–19 in recent years, he observed, with 9.1 percent falling into this category (Ogden et al., 2016). Children with severe obesity are more likely to have severe obesity as adults, he continued, and as seen in Figure 5-1, BMI during adolescence predicts cardiovascular-related mortality risk later in life (Twig et al., 2016). Citing findings from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (Teen-LABS study), he reported that children or teenagers who were about to undergo bariatric surgery as part of this study had a high prevalence of

SOURCES: Twig et al., 2016. Presented by Marc Michalsky on April 6, 2017. Reprinted with permission from the Massachusetts Medical Society.

dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, joint pain, hypertension, and other comorbidities (Inge et al., 2014b). Phentermine is approved for use in children aged 16 and above, he noted, but is rarely used within the pediatric setting. In addition, he said, very few adolescents undergo bariatric surgery, even though evidence “supports the paradigm of at least considering bariatric surgery as an effective treatment modality for this particular subpopulation.”

Adolescents need “an effective means of losing weight,” Michalsky asserted. He reported that according to recently published 3-year longitudinal data, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy produce not only significant weight reduction over time but also a 90 percent remission rate for type 2 diabetes, a 77 percent remission rate for prediabetes, a 66 percent remission rate for dyslipidemia, and improved blood pressure and kidney function (Inge et al., 2016). Surgery does bring certain complications and risks, he acknowledged, such as micronutrient and macronutrient deficiencies, but that “speaks to the importance of being able to remain engaged with these patients long term.” In this regard, he noted, the issue of children going to college or moving out of state permanently is a problem, both in following them up after surgery and following them up when they are on medication.

Michalsky observed that the consensus regarding bariatric surgery for adolescents has changed over time. He pointed out that Inge and colleagues (2004) took a conservative approach to eligibility. Since then, however,

the consensus has developed to be similar, but not identical, to the adult criteria, with particular attention to such issues as Tanner staging, skeletal maturity, lifestyle changes, and psychosocial factors (Michalsky et al., 2012; Pratt et al., 2009). Michalsky noted that in 2014, the Adolescent Bariatric Surgery Designation Center was established by the Metabolic and Bariatric Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons and the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, which have published standards for optimal care of the metabolic and bariatric surgery patient. These standards were updated in 2016 (American College of Surgeons and the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, 2016). The result, Michalsky explained has been an increasing number of centers in the United States that have been specifically designated as places where adolescent patients can receive bariatric care.

Michalsky identified as the most important issues access to care and varying attitudes related to patient referrals. He noted that adolescent bariatric surgery has plateaued over the past decade (Kelleher et al., 2013). “There is more and more evidence that bariatric surgery for the pediatric population is good,” he said. “But somehow or another it doesn’t seem to be reflected in increased prevalence rates.” Insurance is one challenge, he asserted. According to the Teen-LABS study, insurance authorization at original request is only about 47 percent, compared with more than 85 percent in adult populations (Inge et al., 2014a). Eighty percent of these denials ended up being approved, Michalsky added, but sometimes only after as many as five appeals. “There are some real disparities here,” he suggested.

According to Michalsky, the reason cited most commonly for denial was being less than 18 years old, which he believes reflects the attitudes of pediatricians and family practitioners. He reported that 48 percent of survey respondents in this group of physicians said they would never refer an adolescent patient for a bariatric procedure, and 46 percent endorsed a minimum age of 18 for such surgery (Woolford et al., 2010). Virtually all respondents endorsed participation in a monitored weight management program prior to referral for weight loss surgery.

Nonetheless, Michalsky argued, high-quality data support the use of weight loss surgery in the pediatric population. He added that consensus-driven, best practice guidelines and national accreditation standards have been established and appear to be working well. Yet, he noted, the numbers of procedures have been relatively stable despite these favorable outcomes and standardization of care. “Efforts should be undertaken to increase both public and professional awareness related to this treatment modality as an effective means to help our patients,” he asserted. “We need to do a better job messaging. . . . Bariatric surgery needs to become part of the vernacular that primary care providers are familiar with.”

This page intentionally left blank.