3

Proposed Priorities and Persistent Challenges Related to Health Security

There are a range of threats to the nation’s health security that have the potential to cause widespread disruption and damage to human health, the economy, and society at large. As noted by Inglesby, great strides have been made toward improving health care and public health systems and capacities across the public and private sectors. In this chapter, experts representing a variety of sectors discuss their perspectives on the priorities and persistent challenges related to health security, focusing specifically on health care and public health critical infrastructure protection, data collection and use, funding for health security programs, preparedness for global health emergencies, and vulnerable populations and community resilience. Ensuring a robust health care and public health sector will greatly advance the nation’s ability to respond and recover when faced with a health security threat.

HEALTH CARE AND PUBLIC HEALTH CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION

Laura Wolf, chief, CIP Branch, ASPR, HHS, provided a definition of critical infrastructure as “systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating impact on national security, economic security, public health or safety, or any combination of those matters.”1 She emphasized that critical infrastructure encompasses not only physical buildings, but the

___________________

1 § 1016(e) of the USA Patriot Act of 2001 (42 U.S.C. § 5195c(e)).

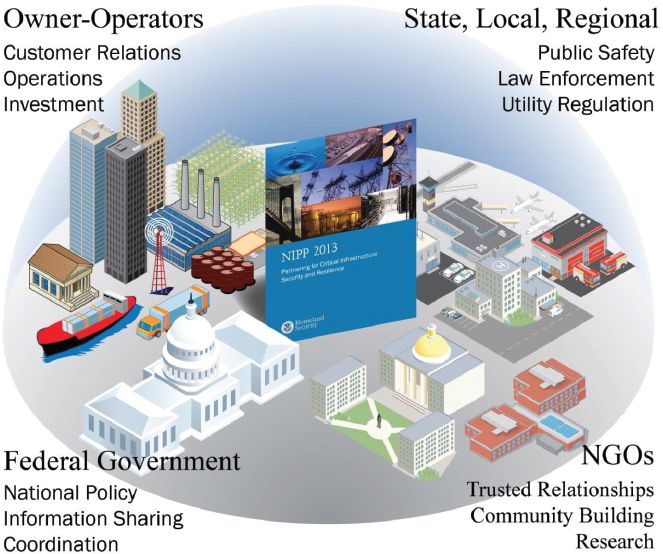

NOTE: NGO = nongovernmental organization.

SOURCES: Wolf presentation, March 8, 2017; U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

systems and assets that are fundamentally required to perform the functions needed for public health and safety.2 She reflected that 2.5 million people per day access health care and public health critical infrastructure.

Wolf described the national-level health care and public health CIP foundation as an instructive model of partnership to promote capacity building and preparedness (see Figure 3-1).

The HHS/ASPR CIP Program works with government and private-sector partners to enhance the security and resilience of the health care and public health sector by mitigating risks to critical infrastructure.3

___________________

2 For example, Wolf noted, going to a medical office for treatment in a facility that has power and water; where staff take health insurance information and access electronic health records; where a doctor uses lab tests to make a diagnosis; and if treatment is needed, where prescriptions are easily transmitted to a pharmacy that has the needed supplies in stock.

3 More information about the partnership and the 2015–2018 health care and public health sector–specific plan is available at www.phe.gov/cip (accessed August 8, 2017).

This voluntary partnership is not tied to regulation or funding and seeks to address crosscutting issues not only in the health care field, but also to examine its interdependencies (such as power, water, transportation, and research and development) and to determine ways to better respond to all types of activities. Joint working groups4 of the Government Coordinating Council, which is composed of public-sector components with an interest and role in health care and public health sector critical infrastructure security and resilience, and the Sector Coordinating Council, which is a self-organized and self-governed council of health care and public health private-sector partners,5 are convened routinely as part of the Critical Infrastructure Partnership Advisory Council and are exempt from the Federal Advisory Committee Act. Although activities are communicated to the public, business-sensitive information is protected, which builds trust among partners.6 CIP’s structure connects it with 15 other sectors of critical infrastructure and during a response, FEMA’s National Business Emergency Operations Center brings these sectors together.

The essential components of critical infrastructure, according to Wolf, are “staff, stuff, systems, and space.” Staff includes office personnel, doctors, truck drivers, manufacturers, information technology (IT) security, and researchers. Stuff covers, for example, rapid flu tests, gloves, swabs, drugs, blood supply, and vaccines. Systems comprise transportation, health insurance, health IT, supply chains, research and development, and funding. Space involves medical and public health buildings, security, power and water, pharmacies, distribution hubs, and laboratories. Wolf also described the multiple health care and public health subsectors at play in critical infrastructure: direct patient care, pharmacies, laboratories and blood banks, health IT, medical materials (distributors, manufacturers, and materials managers at facilities), plans and payers, mass fatality management, state and local public health departments and related associations, and federal response and program offices.

Oscar Alleyne, NACCHO, noted that from a local health department lens, the “staff” element of critical infrastructure means ensuring there are enough trained staff on the ground to respond during an emergency while maintaining continuity of operations with regular programs and services. Dave Dyjack, executive director, National Environmental Health Association, used the environmental health workforce as an example of the benefits gained by bringing the right people to the table in the preparedness,

___________________

4 Joint working groups include a Risk Management Working Group and Cybersecurity Working Group.

5 Sector Coordinating Council workgroups include Activate Shooter, Situational Cybersecurity, Legislation, and Supply Chain.

6 The CIP Advisory Council charter is available at https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/cipac-charter-11-30-16-508.pdf (accessed August 8, 2017).

response, and recovery enterprise. He recounted that a FEMA call after Hurricane Matthew for workers and volunteers in October 2016 included a wide range of sectors but that environmental health professionals who work with these sectors daily were not included in the call. “The challenge that we have is that we don’t invite environmental health professionals to the table early. We don’t recognize them as a resource,” he said.

Dyjack stressed that public health is environmental health and that the environmental health sector comprises the largest part of the public health workforce.7 Environmental health professionals are in the field every day, understand the culture and the risks, and in many cases have locally funded data-collection systems in place. Environmental health also needs to be part of continuous quality improvement issues, he argued. As innovative techniques are introduced, the environmental health and clinical care sectors should work together systematically to validate, assess, and measure intervention effectiveness. He commended the University of Nebraska’s National Ebola Training and Education Center for inviting environmental health and industrial hygienists to the table early on to address issues related to the transmission of Ebola in those environments.

Wolf illustrated the evolving threat to the supply chain of health care and public health critical infrastructure. Different products, supply chains, people, and networks were factors in the range of responses to evolving threats over the past 10 years. The 2009–2010 H1N1 pandemic highlighted the need for syringes, needles, and masks. The 2013 saline shortages called attention to gaps in access to saline products in the event of an emergency. The 2014 Ebola virus crisis in western Africa showcased the need for access to personal protective equipment in the midst of hoarding and supplying challenges. The 2016 Zika outbreak, which focused on prevention, called attention to gaps in vector control. Wolf emphasized that each of those responses to evolving threats was contingent on access to supplies through public–private partnerships. Partnering in the health care and public health enterprise requires coordination among and between the public sector (e.g., VA, DoD, CDC, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, NACCHO), private sector (e.g., Healthcare Industry Distributors Association, Consumer Specialty Products Association, and the Medical Device Manufacturers Association), and coordinating groups (e.g., PHEMCE, the Global Supply Network for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, and the All-Hazards Consortium).

Gregg Margolis, director, Division of Healthcare System Policy, HHS, provided an overview of the substantial and cascading impacts that disasters have on health care and public health systems. He explained that al-

___________________

7 Dyjack cited the Bureau of Labor Statistics and said there are about 88,000 environmental scientists in the country. The next closest group is public health nurses at around 40,000 to 45,000.

though each disaster is different, they have certain common characteristics. A rapid influx of patients with unscheduled needs can stress health care systems in ways no other events can. Disasters cause many acute injuries in people who are displaced from their regular sources of care and seek care in emergency departments without access to their medical records. Large numbers of people affected by a disaster may be from vulnerable populations and/or have chronic comorbidities that exacerbate and lengthen care requirements. Evacuations and interruptions in the normal health care infrastructure due to disasters can also debilitate health care systems, he noted. As seen in the Ebola and Zika epidemics, disasters give rise to many challenges related to information needs, such as disseminating information and clinical algorithms that are evolving during an event to clinicians providing care and making decisions beyond their normal responsibilities.

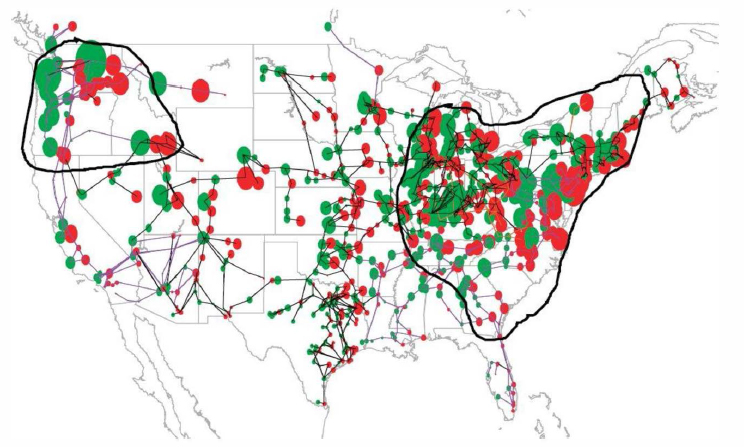

John Hick, medical director, Emergency Preparedness, Hennepin County Medical Center, emphasized that the “space,” or physical infrastructure, is a fundamental necessity—for example, power and water are required to provide care. He outlined a set of “mission-essential functions” for physical infrastructure and facilities: structure, utilities, heating and air-conditioning, air handling, medical gases, telecommunications (Internet, and IT systems), electronic health records (EHRs), medical supplies, transport, nutrition, pharmacies, laboratories, radiology, security, laundry, human resources, and environmental health. Hick warned that risk is endemic in the United States, with large populations living in areas that experience significant natural hazards and others living in areas that are part of large infrastructure networks (e.g., electricity) at risk of technological hazards. Hick expressed grave concerns about the reliability of the aging utilities infrastructure in the United States. For example, if a coronal mass ejection occurred matching the May 1921 geomagnetic storm level (not even at a greater magnitude like the Carrington event, a solar storm in 1859), then 130 million people would lose power for weeks or months at a time, mainly across the eastern half of the United States and the Pacific northwest (see Figure 3-2).

Hick explained that the level of event in this model would have a dramatic impact on health care and public health critical infrastructure. Electricity has no specific sites for public access because it is a public service, not a private enterprise (similar to health care, but more widely distributed). He explained that even short-term blackouts cause consistent cascading failures in infrastructure and systems.8

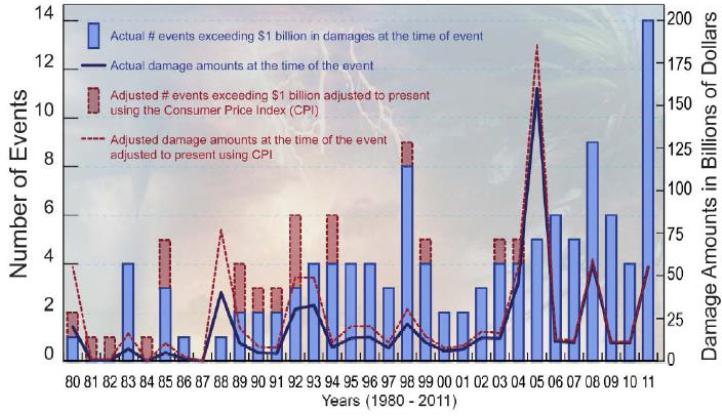

Hick also warned that trends for billion-dollar climate disasters are

___________________

8 For example, Hick described a person on electricity-dependent oxygen at home who must come into the hospital and vendor chains falling apart because gasoline is not available. Hospitals are not used to running at 100 percent on their generators and they usually do not have appropriate generator support to back up their HVAC systems.

NOTE: The regions outlined are susceptible to system collapse due to geomagnetically induced current. The impacts would involve populations in excess of 130 million.

SOURCES: Hick presentation, March 8, 2017; Geomagnetic Storms and Their Impacts on the U.S. Power Grid, January 2010.

increasing, with four of the five most powerful hurricanes in recorded history occurring within the last decade. As ocean waters warm, storms will become more intense and will remain intense farther northward than ever before (see Figure 3-3).

Presenters and participants identified persistent difficulties related to assessing, protecting, and strengthening the existing health care and public health critical infrastructure, as well as strengthening stakeholder engagement in national-level discussions about health security. Rear Admiral Carmen T. Maher, acting assistant commissioner for Counterterrorism Policy, FDA, suggested that critical infrastructure sustainability requires ensuring accountability, objectively evaluating systems in place to adapt or augment obsolescence or ineffective pieces, and investing in integrating preparedness and response components in day-to-day and other systems across the public and private sectors. She noted that the systems carrying out day-to-day safety, efficacy, and data collection also have both the funding capability and structure to surge up and serve during emergencies.

Deborah Levy, professor and interim chair, Epidemiology Department, University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Public Health, noted

that preparedness and response are often considered too separate and distinct from the day-to-day operation of health care and public health critical infrastructure, especially in terms of funding, but she suggested that those basic, everyday needs must be met before thinking about and devoting resources for preparedness or emergency response. David Abramson, professor, Center for Global Health, New York University, agreed about the need for health and human services systems to respond to community needs, both routine and during an emergency.

Roy Alson, Wake Forest School of Medicine, pointed out that communities with health care systems that are able to provide effective care on a routine basis are better prepared to respond to disasters. However, he explained that many components of health care and public health critical infrastructure are situated in systems that are stressed and often inadequate on a daily basis. Asking leadership and the public to commit more resources to strengthen the system for potential disasters in the face of daily systemic insufficiencies presents a conflict, he warned, and surmounting it will require taking a broader view and working to fix the entire system: “As we talk about preparedness and our ability to respond to unplanned or even unanticipated events, we must do it in the entire context of how to manage our day-to-day disasters.”

SOURCES: Hick presentation, March 8, 2017; U.S. Billion-dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Data Sources, Trends, Accuracy and Biases. Introduction (p. 338). Natural Hazards, June 2013, Volume 67, Issue 2, p. 338.

John Osborn, operations administrator, Department of Practice Administration, Mayo Clinic, commented on awareness and recognition of the importance of health care and public health among the other sectors of critical infrastructure. He noted that because the systems are so tightly integrated, attempting to separate out one problem to solve will not accomplish much. He also remarked on the extent to which other sectors of the economy do not realize they require health care services and further suggested that spending a fraction of the investments being made in those other sectors on public health could potentially relieve the overburdened public health system. Laura Runnels, LAR Consulting,9 noted the persistent struggle of clearly demonstrating and communicating the value of health care and public health to the public, the private sector, and the government. Dyjack highlighted the near absence of recognition of public health. For example, no one contracted and died of Ebola virus in the United States during the worldwide pandemic, but this successful solution was not recognized or celebrated as it would be in other professions.

DATA COLLECTION AND USE

Margolis explained that data collected from a disaster comes in different forms that include EHRs, but also draw from “operational data, administrative data, scheduling data, workforce data, inventory management data.” Public health departments are effective when it comes to technical components of data interoperability platforms, noted Lee Stevens, director, Office of State Policy, Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT, HHS. He continued that problems arise with “consistent data formats and particularly around data quality.”

Stripling gave the example of the New York City health department’s use and value of data in their preparedness planning and, ultimately, evaluation. He commented that “in the city health department, what we are doing is we are laying out all of the consequences that we know we are fighting against. . . . It is creating a big data set of thousands of activities literally that we performed over the last decade. But by putting those in data, we make them queryable-like data, tagging them like data. We are talking [about an] all hazards data warehouse that we can then connect to all the other data that we are dealing with. When we run our preparedness cycle, we base it on those activities. And in response, we can evaluate those activities.”

Hu-Primmer described efforts to address one aspect, a comprehensive, governmentwide coordinated capability to monitor and assess MCM use

___________________

9 Laura Runnels is a consultant facilitator hired by the National Academies to assist with group process and to offer her own observations on themes as a participant of the workshop.

(including safety, compliance, and clinical benefit) through data collection and analysis during and after an emergency event. These data would enable better assessment and decision making during both present and future public health responses. Such an effort requires a comprehensive governmentwide centralized and coordinated capability—a “middle lane”—to bridge the gap between limited (or a lack of) data collection during a public emergency and traditional randomized controlled trial data collection. This middle lane is important, she explained, because it is nearly impossible to rely on traditional data collection; it is extraordinarily difficult to execute randomized controlled trials in the absence of an emergency, let alone during an emergency. Limited anecdotal data or emerging information are plagued by questions over the reliability and robustness of that data. The middle lane will be required to carry out coordinated, predefined, predetermined data collection and to create abbreviated case reports for prospectively defined fields and nested protocols. She reported that the U.S. government is already taking steps to establish this middle lane by using the “crawl-walk-run” paradigm: define the needed dataset; develop a simple protocol to collect the needed dataset; send the protocol to local institutional review boards (IRBs) for review; develop reliance agreements between local IRBs and a centralized IRB; and then preposition the IRB-approved protocol and exercise on a yearly basis.

Margolis noted that in today’s environment, health care executives have better situational awareness about what is going on within their facilities than ever before. However, this information is not routinely shared due to several reasons (i.e., the information is proprietary). As a result, Margolis remarked, “We have an amazing blind spot in our health care system: virtually no health care situational awareness. There is no one that has a view of what is going on in the overall health care system. We do not really understand what the capacity, capability, and stress on health care systems are every day or during disasters. . . . If you can’t do it every day, you won’t be able to do it during a disaster.” He defined health care situational awareness as understanding the capabilities, capacity, and stress on health care organizations in a given geographical area.10

Multiple participants highlighted the challenge of striking the right balance between having enough versus too much data. Runnels observed that public health does not always have the type of data it needs; for example, most local health departments do not have access to EHRs. Furthermore,

___________________

10 Margolis explained that this gap in situational awareness is evident during an emergency, when state, local, and emergency management need real-time, detailed information about hospitals: “What hospitals are open/closed? Who is evacuating/sheltering-in-place? What hospitals are on auxiliary power? At capacity, near capacity, how many more patients can they take? What is the critical care capacity? Pediatrics? How many ventilators do they have? Do they have adequate supplies? What is running out? Are the staff able to get to work?”

she suggested that lack of data may lead other entities to perceive public health as vulnerable, and this perception may undercut public health’s authority and involvement in a community. She also commented on the challenges of data timeliness and accuracy: “Either we do not have enough, or it is not coming to us quickly enough, or we have too much and it is changing all the time.” Stripling characterized this national-level problem as the “data rabbit hole”: there are exponentially increasing amounts of data available, but too much data are useless and largely go unanalyzed. Data can also become overwhelming and obfuscate elements of a community’s response, he warned.

Redlener cautioned against overemphasizing data needs for problems that may not need more data to solve, because it can become a tempting screen to hide behind and avoid facing other big challenges. For example, in the hypothetical case of a 10-kiloton improvised nuclear device hitting New York City requiring the accommodation of 50,000 evacuees, he argued that data do not contribute to a macro-level understanding of what evacuees need or how to carry out the evacuation in practice. He argued that many issues related to preparedness, response, and recovery are not amenable to more information or research, but conceded that data are important operationally.11

The democratization of data, Stripling suggested, can also impede a response: “We no longer live in a world where we can follow data to a solution. It is not functional. . . . We must first understand our mission and then hit the data within it.” He cautioned that “dropping the data in the middle of the response” can have serious ramifications, because the democratization of data can lead to misinterpretation by nonexperts. For example, if epidemiologists use data to create a map with a circle on it during a response, it may be perceived by the public, policy makers, and media as a threat rather than a tool for localizing the source of injury: “Everybody thinks that is where people are going to get hurt. That makes it a political objective, not an investigation object.” In some cases, according to Stripling, it is necessary to confine data to the epidemiologists’ sphere because only their expert judgment is useful.

Karl Schmitt, bParati, noted that the challenge of “chasing the data point” can overwhelm and waste limited resources. Redlener pointed to this as another example of the “data rabbit hole”—having large amounts of data without a structured mission to operationalize that data. He illustrated this challenge with a hypothetical situation: during a large disaster, responders have data about a person who is oxygen dependent, but no

___________________

11 For example, Redlener noted data can be useful in determining what a hospital is doing or not doing, what it can accommodate, or where its capacities are being stressed in the midst of an acute emergency in a particular location.

knowledge of the clinical outcomes. If the person does not answer the phone, “Is she lying dead on the floor? Is she perfectly safe and evacuated? We do not know. We go to knock on her door. Her power is out. There is no answer. Do we break down the door? If we find her, do we bring her food? Do we prioritize that person because we have data over another place that we do not have any data about? These are the choices that data lead us to.” Without a clearly established mission, data can effectively paralyze the response. He explained that having a data point about a person does not show one survivor, it shows all the potential survivors who could express that data point: “An oxygen-dependent woman, who might be fine, might not be fine, might have family, might not have family, might have support, or might not have support.”

Several participants also emphasized weaknesses in the system’s current ability to collect, validate, and disseminate data on risk and threat information during emergencies, to integrate advances in research and technology, and to use and collect electronic health data before, during, and after an emergency response. Stacy Arnesen, National Library of Medicine (NLM), NIH, suggested a set of key questions to consider about the role of data in this space: “What is the purpose of data? How do we ensure data match/ help meet the mission? What data are needed? What to collect? What to save/preserve? What tools will assist with interoperability, integration, and analysis?” Maher explained that just as key decisions are different in different emergencies, so are the kinds of data needed to inform those decisions and that the challenge is to find the quickest way to collect and analyze data, look at outputs, and communicate findings. Dylan George, associate director, B.Next, In-Q-Tel, and former senior advisor, Biological Threats Defense, Office of Science and Technology Policy, White House, suggested the need to improve quantitative analytics and data sharing for improved decision making.12 He also noted that data sharing within the federal government, at the state and local levels, and within academia lacks breadth, effectiveness, and nimbleness. Wolf remarked that health care and response are data driven, but data protection and privacy concerns can impede information sharing.

Ongoing broad challenges, according to Levy, include developing better health systems informatics, establishing a common operating picture, and addressing information-sharing needs. Michael G. Kurilla, director, Office of BioDefense, Research Resources, and Translational Research, and associate director for BioDefense Product Development, Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, HHS, suggested the need to better integrate and leverage evolv-

___________________

12 George noted that during H1N1 modeling was not very useful (and in fact confused the response), but during Ebola it had a positive impact and was used to inform decision making.

ing technology. Maher noted the challenge of building technical and human resource infrastructures that can manage all the different data streams and help to prioritize and select the most relevant ones. Redlener highlighted the hour-to-hour dynamic reality of the collection and accuracy of data (e.g., last week’s functional disability list is no longer current), which makes it difficult to operationalize data and carry out operational planning. He suggested that a key challenge in addressing this issue will be determining how often data need to be collected from a functional perspective.

Rajiv Ramnath, director, National Science Foundation, raised the issue of the research agenda, research gaps, and whether the need is to collect new types of information or to integrate the information that is already available. Jesse L. Goodman, professor of medicine, Georgetown University, also remarked on the challenge of defining and disseminating science gaps and the research agenda. Levy noted that rigorous, evidence-based evaluation and study design tend to be ad hoc in preparedness as compared to other parts in the public health arena.

FUNDING FOR HEALTH SECURITY PROGRAMS

Several workshop participants discussed and explored the challenges in financing and sustainability of health security and preparedness. Dara Alpert Lieberman, senior government relations manager, Trust for America’s Health, reported that her organization’s latest annual preparedness report, Ready or Not? Protecting the Public’s Health from Diseases, Disasters, and Bioterrorism,13 discusses an established pattern within public health financing. Overall baseline public health funding is cut, and then a new crisis arises for which Congress may provide supplemental funding; once the crisis passes from national attention, the system reverts to budget cuts. Hick advised, “You get what you pay for in the end with public health and with emergency preparedness. If you don’t want to invest, that is fine, but with no investment there is no return. There will be failures.”

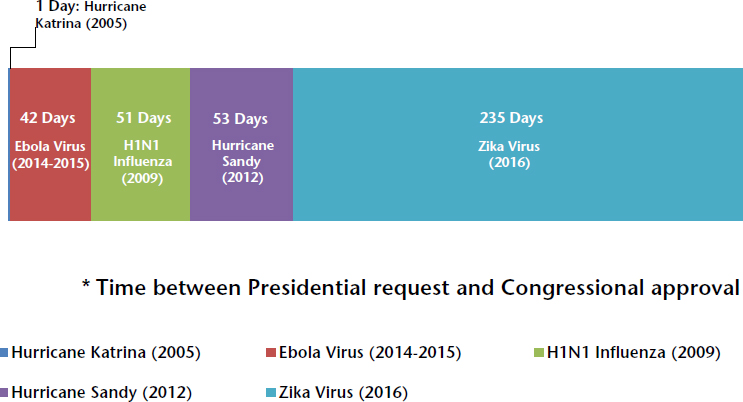

Disease can spread nearly anywhere within 24 hours through the global aviation network, and both natural disasters and terrorist events can hit with no warning, cautioned Lieberman. She explained that the common factor in all types of crisis events is that time is critical for mounting a robust, immediate public health response. Such a response requires having access to funding, supplies, and people in place as soon as possible after event onset. However, she explained that for various political reasons, Congress generally does not move quickly enough in funding an immediate response. For example, it only took 1 day for Congress to respond to then President

___________________

13 See http://www.healthyamericans.org/assets/files/TFAH2012ReadyorNot10.pdf (accessed August 8, 2017).

George W. Bush’s request for a Hurricane Katrina supplement, but nearly 8 months lapsed between then President Barack Obama’s initial request for Zika response money and the final Congressional approval (see Figure 3-4).

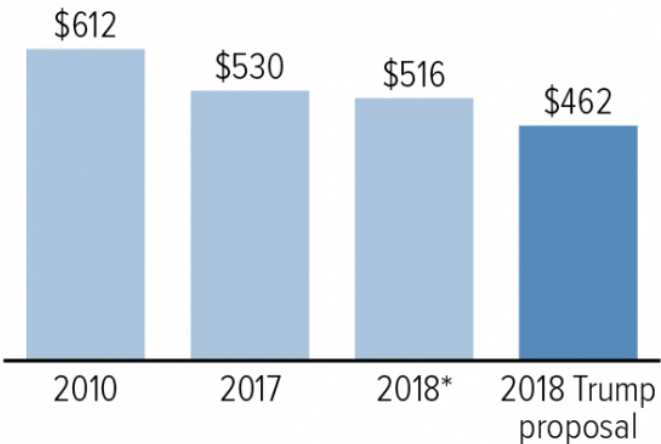

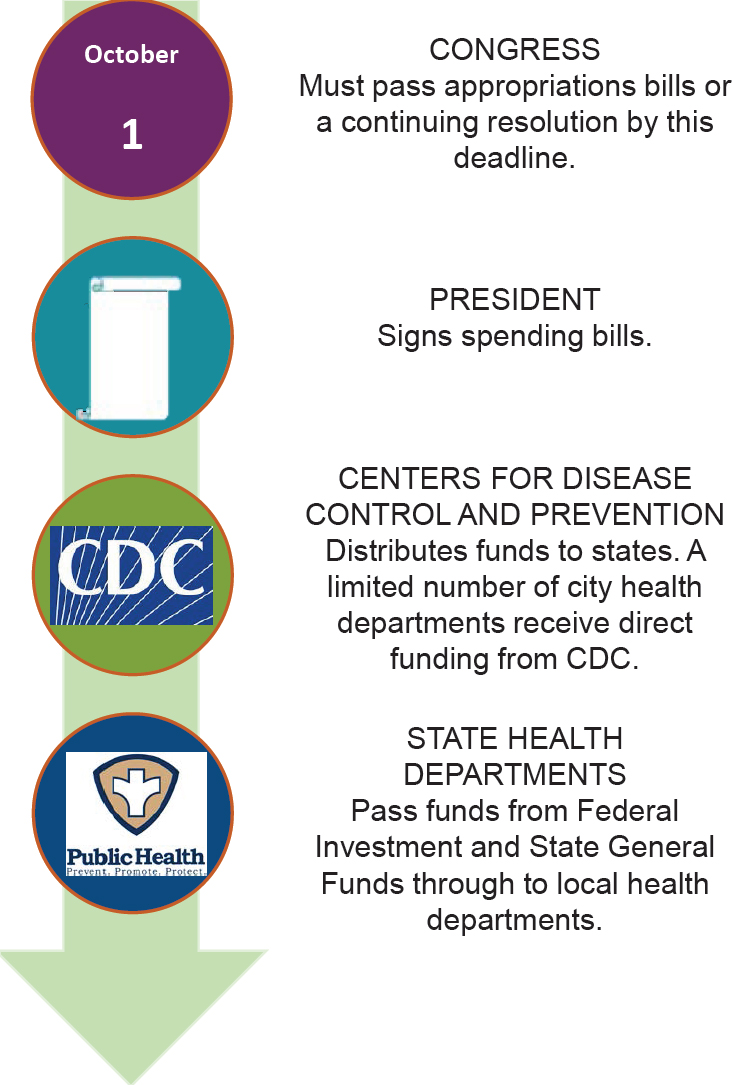

Lieberman explained that public health funding for preparedness is tied into larger overall federal budget and debt reduction conversations. Fiscal year (FY) 2018 is a sequester year with tight funding caps, so the macro-level funding issues will have a cascade effect on all nondiscretionary programs. Hanen reported that nondefense discretionary spending in FY 2018 will reach a record low as a mere one percent of the gross domestic product, with data going back to 1962. Despite this, she noted, President Donald Trump will potentially propose a $54 billion increase for defense programs, with a commensurate decrease in nondefense discretionary programs (see Figure 3-5).

Hanen suggested there may be a silver lining, in that there are policy makers who recognize the need for providing funds for public health programs and are searching for solutions to fund the Preparedness Enterprise. For example, she quoted Chairman Kohl of the Labor–HHS Appropriations Subcommittee in the House of Representatives as opposing President Trump’s approach of a commensurate cut in nondefense spending with a commensurate increase in defense spending, and stating that CDC is as

SOURCES: Lieberman presentation, March 9, 2017; reprinted from Ready or Not?: Protecting the Public from Diseases, Disasters, and Bioterrorism, http://healthyamericans.org/reports/readyornot2016 (accessed October 3, 2017).

NOTES: Measured in billions of 2018 dollars; * = funding level set in 2011 Budget Control Act, which establishes sequestration cuts; data source = CBPP analysis of data from the Congressional Budget Office and the Office of Management and Budget.

SOURCES: Hanen presentation, March 9, 2017; reprinted from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (cbpp.org).

important to defending the average American as the DoD: “You are a lot more likely to die in a pandemic than a terrorist attack.”14

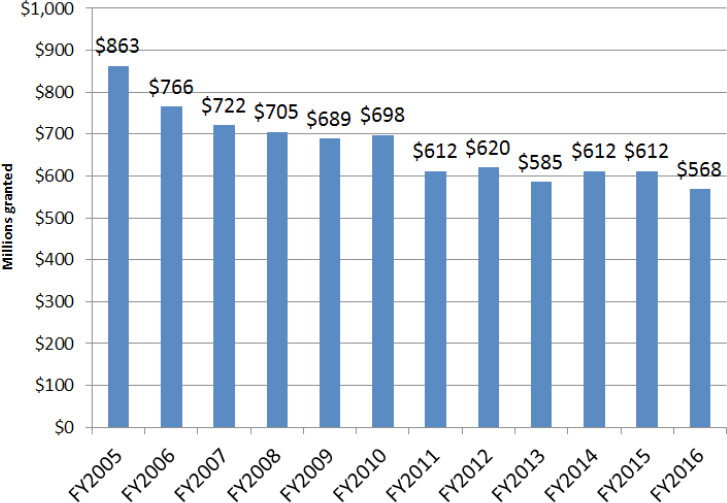

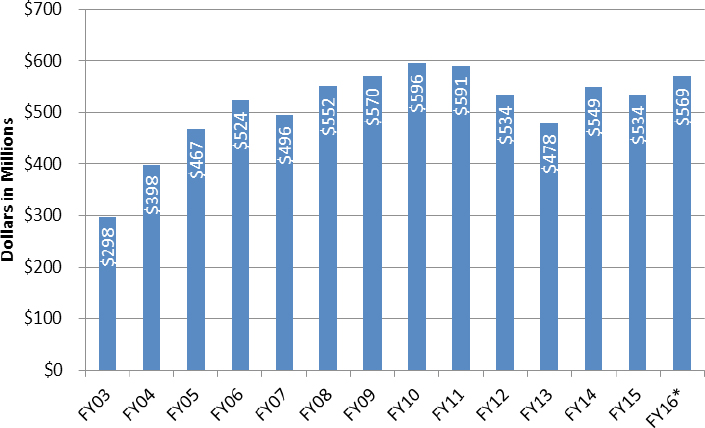

Hanen provided an overview of funding trends in the enterprise through FY 2016. She explained that most health departments receive money through their state health departments, with 55 percent of local health departments relying solely on federal funding. There has been a 34 percent reduction in PHEP funding over the last decade, and she noted that this lack of sustained and robust funding presents problems when issues arise and Congress must be asked for resources (see Figure 3-6).

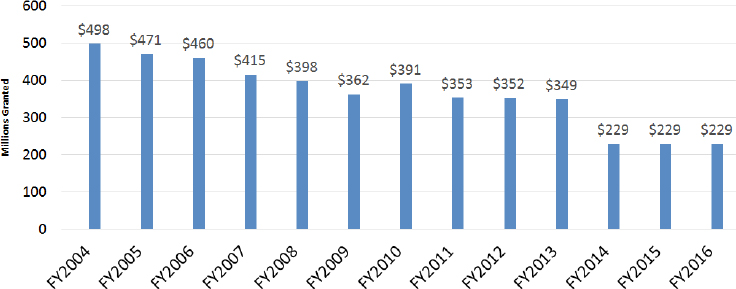

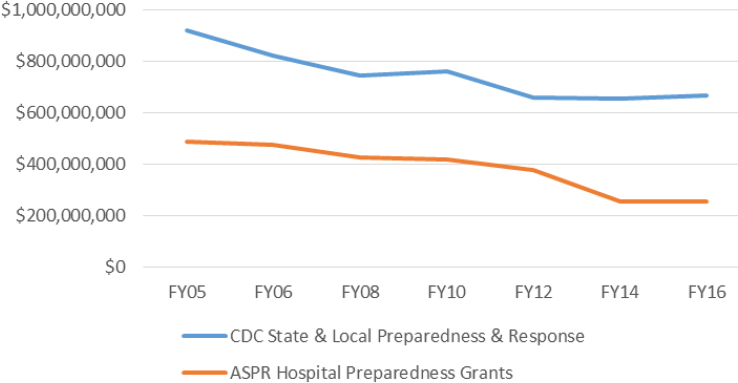

Cuts to the ASPR’s HPP in recent years have also hampered the pursuit of robust health system preparedness with health care coalitions, noted Hanen. Funding was decreased by $104 million (29 percent) in FY 2014

___________________

14 When asked about the 12 percent cut to CDC’s budget as a result of the Prevention to Public Health Fund, Chairman Kohl said, “Having a robustly funded CDC is very much in the national interest.” He also put in a $300 million bill in 2017 for an infectious disease rapid response fund in CDC.

and by 54 percent over the last decade, depending on the benchmark in the federal budget bill (see Figure 3-7).

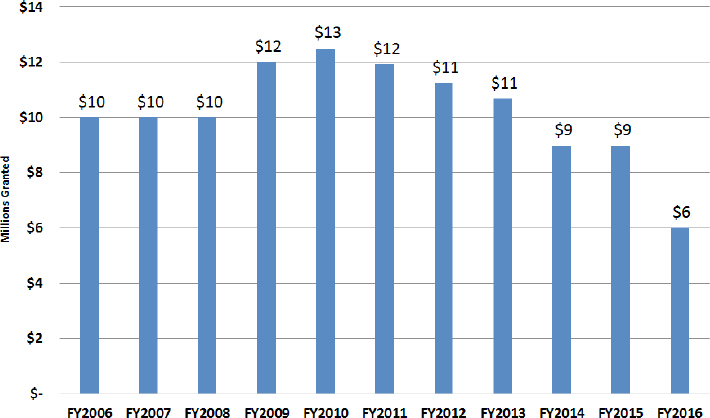

Two-thirds of the MRC units, another piece of the Preparedness Enterprise, are based in local health departments. Hanen explained that MRC units include volunteers who work with local departments to extend capacity by staffing points of dispensation, such as flu clinics. MRC funding has also been cut over time, including a $3 million cut in FY 2016 from FY 2015, representing a 40 percent decrease from FY 2006 (see Figure 3-8).

The Strategic National Stockpile will need continued resources to maintain, replenish, and provide additional licensed products to the stockpile, according to Hanen. These are discretionarily appropriated programs that require “going back to the well” annually (see Figure 3-9).

BARDA, which is housed within ASPR, facilitates the development and purchase of therapies, vaccines, and diagnostic tools for public health medical emergencies. Hanen noted that BARDA was originally funded through an advanced appropriation of a transfer from Project BioShield that expired

NOTES: Measured by $ in millions granted; 34 percent cut in funding since FY 2005.

SOURCES: Hanen presentation, March 9, 2017; NACCHO based on funding awards.

NOTES: Measured by $ in millions granted; 54 percent reduction since FY 2004.

SOURCES: Hanen presentation, March 9, 2017; NACCHO based on funding awards.

at the end of FY 2013. Currently, BARDA is also reliant on the annual budget appropriations process. She emphasized that during tight budget times with budget caps, the appropriations process amounts to a zero-sum game that pits all these programs against one another for funding.

Inglesby and others endorsed the concept of using the public health emergency fund (PHEF) as a means to quickly fund an emergency response. Lieberman provided an overview of the potential benefits and drawbacks of this solution. She noted that some have likened PHEF to FEMA for public health emergencies, but her organization, Trust for America’s Health, views it as a surge fund to supplement rather than supplant. This distinction means it complements but does not replace sufficient, stable funding and is meant to serve as a bridge between the onset of an emergency and (if necessary) supplemental funding. She explained that under existing authority (1983), the Secretary of HHS would control the no-year fund and be required to report to Congress on how the money is spent. However, no money has been provided to the existing PHEF since FY 1999. She suggested that the lack of designated funding may be one of the reasons why more public health emergencies are not declared. However, she noted that there have been proposals in Congress during spring 2017 that could address this problem. She highlighted the bipartisan Public Health Emergency Response and Accountability Act (Senators Bill Cassidy and Brian Schatz), which includes a funding formula that looks at the past 14 years of public health emergency spending (approximately $1.5 billion to start). Funding would be controlled at the HHS department level and could be used

NOTES: Measured by $ in millions; 40 percent reduction since FY 2006.

SOURCES: Hanen presentation, March 9, 2017; NACCHO based on funding awards.

NOTE: *FY 16 listed at the President’s Budget level, pending final appropriation.

SOURCES: Hanen presentation, March 9, 2017; from CDC.

for any state, national, or international declared public health emergency response.15

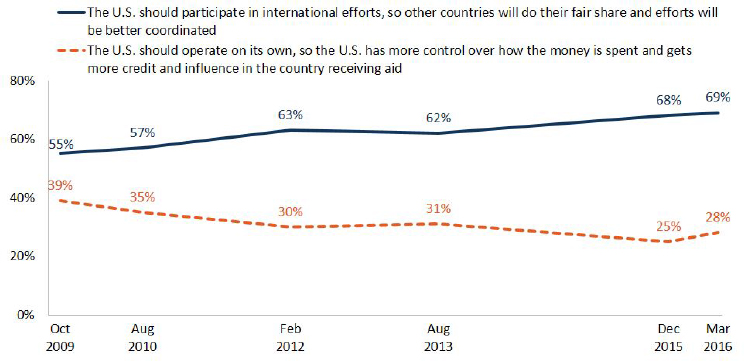

Lieberman outlined some of the benefits of PHEF. It can help federal, state, and local public health officials address a crisis without having to wait for Congress, so that politics do not stand in the way of the public’s health. It can jump-start response efforts because money could be quickly moved to meet the immediate needs of the crisis.16 Finally, biotechnology companies interested in researching MCMs would have some reassurance of funding stability. However, she warned that there are also potential drawbacks. Because many policy makers do not understand the distinction between preparedness and response, they may consider PHEF to be the solution to other problems, and it might be used as an excuse to cut base preparedness funding. This attitude is problematic because since FY 2005, CDC state and local preparedness funding has declined by almost one-third, and ASPR HPP funding has been cut nearly in half (see Figure 3-10).

Lieberman emphasized that funding delays have real consequences on the effectiveness of public health emergency response. Delays in distributing emergency funds not only hamper the response, but they can also stifle research and discourage involvement in the biotechnology industry. For example, one of the major consequences of the delay in the Zika virus response was that as Congress took longer and longer to appropriate money, biotechnology companies became less interested and less willing to become involved in Zika virus countermeasures research. This loss of interest hindered not only the short-term response to the Zika virus, but also long-term partnerships with those companies. She cautioned that having public–private partnerships in place in the MCM space is critically important as there is no other natural marketplace for those products, and the industry needs reassurance that the government will be a reliable partner and provide necessary funding throughout the research process. Delays in emergency funding also hurt other priorities, Lieberman noted. During PHEP reprogramming, the Zika virus response was maintained by moving $44 million from the All Hazards account. NACCHO and other organizations carried out a survey of their members to better understand

___________________

15 Other proposals Lieberman and Hanen discussed included the FY 2017 House Labor–HHS CDC Infectious Disease Rapid Response Reserve Fund, which puts $300 million into CDC infectious disease rapid response (overall public health funding would also be cut, including for infectious disease); the Public Health Emergency Preparedness Act (Representative DeLauro), which would put $5 billion into PHEF; and the CDC Emergency Response Act (114th Congress) (Senator Boxer, retired), which would put $2 billion into a CDC-controlled fund.

16 Lieberman noted that there may be many different types of public health emergencies warranting funding than are traditionally considered (e.g., the opioid epidemic; the Flint, Michigan; water crisis) that may qualify for PHEP.

NOTE: ASPR = Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

SOURCE: Lieberman presentation, March 8, 2017.

the impacts of the redirected $44 million.17 She reported that according to the survey, areas most negatively affected by PHEP funding reprogramming were pre-event readiness (74.7 percent), supplies (54.6 percent), staffing levels (47.2 percent), functional preparedness program levels (34.6 percent), and contractual services (23.5 percent). She noted that these cuts occurred in areas that could not easily be backfilled.

Lieberman stressed the importance of impressing upon policy makers that short-term, supplemental funding for a crisis cannot take the place of ongoing preparedness efforts. For example, in the years before the emergence of the Zika virus, funding for mosquito-borne surveillance was cut from $24 million to $10 million (2004–2012). A state or local health department cannot maintain a mosquito surveillance program with that type of short-term funding, she cautioned. A further concern is that the no-year fund might be viewed as an attractive funding source for Congress or HHS even with limitations incorporated into the statute to prevent another outbreak. For example, the unspent Ebola outbreak supplemental funding should have been spent on continued efforts in West Africa, but was instead

___________________

17 See the impact of the redirection of public health emergency preparedness (PHEP) funding from state and local health departments to support national Zika response at http://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Impact-of-the-Redirection-of-PHEP-Funding-to-Support-Zika-Response.pdf (accessed August 8, 2017).

shifted to the Zika virus response, and the funding for the BioShield Special Reserve Fund has instead been used for BARDA research and development.

Pressures on the discretionary budget may also lead to major cuts to public health funding, Lieberman warned. If the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is repealed, the repeal of the Prevention and Public Health Fund will create a nearly $1 billion shortfall in CDC’s budget that will affect foundational public health capabilities in ways that short-term supplemental funding cannot cover. She stressed that PHEF can only solve the problem of delayed supplemental funding by serving as a potentially incomplete bridge between the onset of a crisis and the need for supplemental funding.18

Lieberman’s organization recommends that PHEF require sufficient funding to bridge the gap between the onset of a crisis and the availability of supplemental funds, and that such funding must be replenished over time. She stated that moving forward will require clarifying the difference between preparedness and response for lawmakers, clarifying who is in charge between CDC and HHS, addressing bureaucratic challenges in obtaining funding, and establishing appropriate transparency and accountability to ensure that funding is being used as intended.

A critical funding challenge, Hanen argued, is that the U.S. appropriations system is broken. She explained that funding the HHS Preparedness Enterprise requires the passage of 12 spending bills. The U.S. government has been unable to pass those 12 bills in a timely fashion, which has forced a reliance on various types of short-term continuing resolutions to keep the government programs funded for a few weeks at a time.19 She reported that 6 months into FY 2017, there still were no spending bills introduced. The uncertainty causes delays for federal agencies in their planning and spending that trickles down to both state and local health departments and ultimately creates further uncertainty for MCM developers (see Figure 3-11).

Sustained investment is critical to maintain preparedness capacity, said Hanen, but funding for public health preparedness will be affected by the overall deficit reduction debate. Although emergency funding is appreciated, a sustained investment is critical to maintain preparedness capacity in both public health and health care systems. However, due to the reduction in funding for mainstay programs, events such as an Ebola outbreak require going to Congress for emergency supplemental appropriations (e.g.,

___________________

18 For example, Lieberman noted, if there is $1.5 billion from the Cassidy bill, but the Ebola supplement was about $5.5 billion, then Congress may use PHEF as an excuse not to provide supplemental funding in the (rare) event it is needed.

19 Hanen discussed examples such as omnibuses that package all 12 bills together; cromnibuses (combinations of short-term continuing resolutions and other spending bills); and year-long continuing resolutions.

SOURCE: Hanen presentation, March 9, 2017.

5-year emergency supplemental funding of $1.7 billion for Ebola outbreak, domestic, and global response, as well as GHSA). She explained that when the Zika virus outbreak occurred, Congress instructed them to dip into the approved Ebola outbreak response funding to pay for the Zika virus response, and it took Congress 7 months after the initial request to approve a Zika virus supplemental. Although the appropriators provided a 5-year appropriation for the Ebola outbreak response, the funding will likely be spent well before the 5 years is over because Congress had to dip into those resources to fund a different outbreak.

Kathryn Brinsfield, former assistant secretary of Health Affairs and chief medical officer, Office of Health Affairs, DHS, noted that public health is the prerequisite for success in health care emergency preparedness, but it requires convincing people to invest in programs that are difficult to understand. Runnels highlighted the challenge of creating a sense of urgency, particularly among decision makers who have not dealt with emergencies, to make investments and change systems at the local, state, and federal levels. Matthew Wynia, director, Center for Bioethics and Humanities, University of Colorado Denver, observed that striking the right balance of private-sector, local, and federal funding for public health preparedness is a key ongoing challenge. Richard Danila, Epidemiology Program manager and deputy state epidemiologist, Minnesota Department of Health, Council for State and Territorial Epidemiologists, noted that there are many established health care and public health infrastructure gaps and weaknesses, but correcting them requires resources that generally do not exist or will not otherwise be allocated. He stressed that more and better financial arguments and analyses will be needed to change the minds of funders and decision makers.

Shah emphasized the need to adequately fund local public health capacity first, noting that public health departments across the country are suffering because we have not invested in the systems and that local public health capacity is a critical component of on-the-ground emergency response that must be adequately funded. Onora Lien, Northwest Healthcare Response Network, noted that at the community level, the annual funding cycle and different approaches taken by various funding streams make it difficult to create alignment to mobilize all efforts toward consistent and sustained common outcomes.

INTERSECTION BETWEEN DOMESTIC AND GLOBAL HEALTH SECURITY

Shah focused on the local perspective of how global and domestic health come together in communities. In terms of protecting the community, he likened public health to the “offensive line” (largely unknown or behind

the scenes) compared with emergency medical services (EMS), fire, law enforcement, and even health care. Although it is largely invisible, he noted, public health is critical at the local community level beyond preparedness and emergency response.20 Shah explained that economics, education, environment, and engagement, or the four “Es,” are key drivers of health. He highlighted engagement as a key piece, because engaging the community requires connecting the dots between events happening across the globe and things happening rapidly in the community: “Whether it’s refugee health issues, issues about unaccompanied minors, or Zika/Ebola outbreak and the like, we very quickly realize that what’s happening in other parts of the globe is very much impacting our community.”

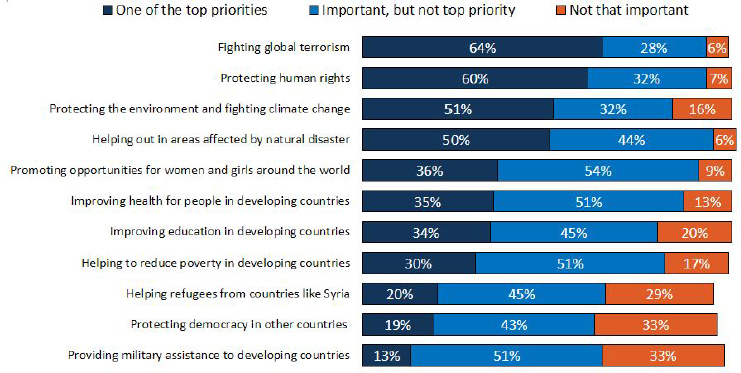

According to Shah and Dan Hanfling, clinical professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, and contributing scholar, Center for Health Security, JHSPH, most Americans support international efforts to improve health in developing countries and other global settings, despite the pervasive politicization of activities and interests (see Figures 3-12 and 3-13).

Shah emphasized the ways in which global interconnectedness affects domestic communities. He noted that the impact on the United States from global events such as infectious diseases is not a new concept. For example, the HIV/AIDS epidemic started as a phenomenon that was not in local U.S. communities but moved to local communities from across the globe in the 1980s. Houston communities have a particularly bidirectional relationship with the rest of the world, he explained, because of community members who are part of the global community: it has a high degree of diversity, busy ports and airports, and a large West African community in Harris County. In the past year, his department spent $1.5 million on multidisciplinary approaches to Zika virus response. As a result of a 7-month funding delay, they were forced to repurpose physicians and other staff in order to respond to the Zika virus outbreak appropriately. Shah observed that ultimately, “The investment in what happens globally, the investment in what happens domestically, and the fact that bidirectionally you have a connection between that global and domestic health front is very much about capacity building.”

Marinissen provided an overview of lessons learned from past disasters and emergencies, which spanned challenges and barriers including legal, regulatory, funding, intellectual property, logistical, information management, ethical, and U.S. government and international coordination. During H1N1 (2009), for example, there were requests for assistance from more than 50 countries; the United States deployed large amounts of H1N1

___________________

20 For example, Shah noted that in Houston, community agencies spray for mosquitoes, pick up dangerous animals, conduct restaurant inspections, address foodborne illness, mitigate threats, administer vaccinations, and so forth.

vaccines and antivirals but faced enormous delays. During the Haiti earthquake (2010), despite claims that medical personnel and public health assets would never be deployed internationally due to legal, regulatory, logistical, and funding barriers, then President Obama deployed resources to Haiti and encountered many challenges. In Fukushima after the nuclear disaster (2011), there was a lack of sufficient information from modeling, discrepant messages from the U.S. government and the government of Japan, and conflicting utilization policies. During the MERS-CoV outbreak (2012), the United States needed but could not obtain samples from Saudi Arabian and South Korean labs to develop and validate diagnostic tools because there was no international consensus on terms and conditions for rapid sample sharing. During the Ebola outbreak (2013), there was a draft framework from Haiti for international deployment, but also new problems that occurred with MCMs, samples, personnel, incident command, and leadership to coordinate public health measures across borders. As a slow-moving event, the Zika virus outbreak (2015) raised the issue of how to start coordinating the research required to mount a response.

NOTE: The prompt was: Which comes closer to your opinion? When giving aid to improve health in developing countries…; Both/Neither (vol.) and Don’t know/ Refused responses not shown.

SOURCES: Shah presentation, March 9, 2017; Kaiser Family Foundation Surveys of Americans on the U.S. role in Global Health, Kaiser Family Foundation Health Tracking Polls.

NOTE: The prompt was: I’m going to read you some different things the president and Congress might try to do when it comes to world affairs. As I read each one, tell me if you think it should be one of their top priorities, important but not a top priority, or not that important; Some items asked of half sample. Not all important (vol.) and Don’t know/Refused answers not shown.

SOURCES: Hanfling presentation, March 9, 2017; Kaiser Family Foundation 2016 Survey of Americans on the U.S. role in Global Health (conducted March 1–26, 2016).

Preparing for the next international threat requires strengthening preparedness and response at the domestic–international interface, according to Marinissen. This preparation is already under way: a global push led to the development of WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, an ASPR-like structure that brings together humanitarian system programs and the IHR community under one line of command to respond to all kinds of public health emergencies. She explained that priority areas include a unified WHO emergency program, a global health emergency workforce, IHR core capacities and resilient national health systems, improvements to IHR, accelerated research and development, and an international financing and contingency fund. The U.S. government has taken an important first step by using international standards and IHR to measure its domestic capacities via the joint external evaluation process, in which external evaluators provided useful feedback about gaps. Marinissen commended this action as representing a significant step forward in opening the doors to the international community and varying points of view.

Rebecca Katz, associate professor of International Health and co-

director, Center for Global Health Science and Security, Georgetown University Medical Center, focused on the challenge of sustaining a commitment to GHSA and its consequences for the future of global health security. She sketched the evolution of GHSA, explaining that the topic was raised in earnest on the political agenda in 2011, when President Obama stated in a speech at the United Nations General Assembly: “We must come together to prevent, detect, and fight every kind of biological danger—whether it’s a pandemic like H1N1, or a terrorist threat, or a treatable disease” (September 22, 2011). This speech, and the momentum behind it, prompted what would eventually become GHSA, which was launched in early 2014 by the United States, 28 other national governments, and 3 international organizations. It is now a partnership of more than 55 countries, with the intent to accelerate progress toward preparing the world for biological threats. She explained that some of these countries are donor states and some play more of a recipient role, but the goal is to come together and contribute to shaping the agenda. The agenda is shaped in part by being organized around capacity building for prevention, detection, and response through 11 action packages with specific targets and metrics according to which countries develop best practices and focus their investments.21

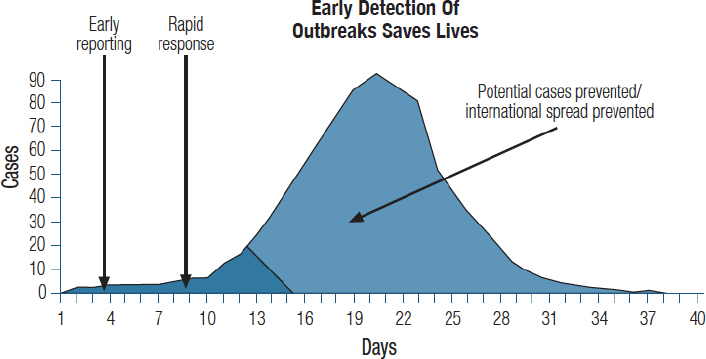

Katz underscored some of the successes already achieved pertaining to GHSA, which has employed the strategy of raising political awareness to mitigate threat. The first success has been marshalling resources, she noted. The United States had a one-time appropriation of $1 billion focused on a set of priority countries; Korea committed to provide $100 million to focus on 13 different countries. The G7 made a commitment to support 76 countries with an undetermined amount of money. Political recognition and coordination have made global health security and response to biological threats part of discussions with heads of states. Through forums such as G20, a series of GHSA high-level ministerial meetings, world leaders are actively discussing the best pathways for reducing biological threats. By marshaling these resources, GHSA has helped to build a national capacity to rapidly detect and respond to biological events. She argued that this rapid detection and response capacity directly translates into being able to save lives in the event of a public health emergency (see Figure 3-14).

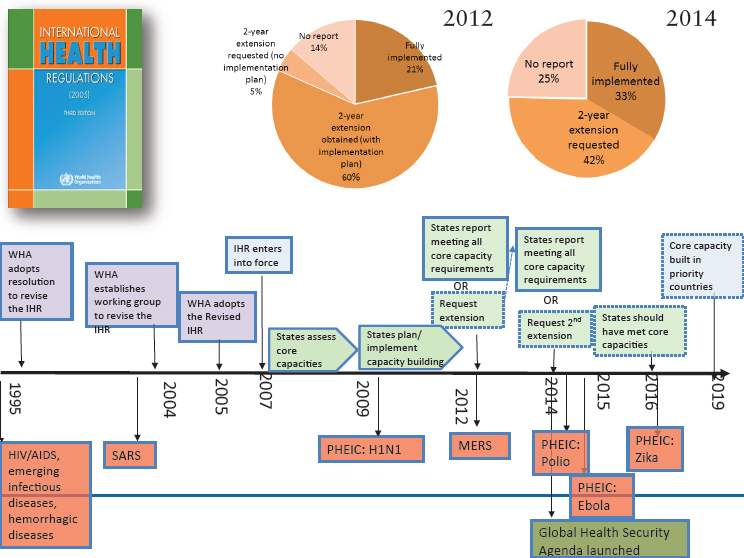

Katz continued that the GHSA has spurred the international community to accept external evaluations of national capacities for prevention, detection, and response. The joint external evaluation tool is now being used in conjunction with the IHR; 29 have been completed so far, 31 more

___________________

21 Katz further explained that GHSA action packages include antimicrobial resistance, zoonotic disease, biosafety and biosecurity, immunization, national laboratory systems, real-time surveillance, reporting, workforce development, emergency operations centers, linking public health with law and multisectoral rapid response, MCMs, and personnel deployment.

SOURCES: Katz presentation, March 9, 2017; The world health report 2007-Global Public Health Security in the 21st Century. A safer future, http://www.who.int/whr/2007/whr07_en.pdf (accessed January 10, 2018). Figure 2 Global outbreaks, the challenge: late reporting.

are in the pipeline, and an additional 27 countries have expressed interest, she reported (see Figure 3-15).

At the February 2017 Munich Security Summit, Hanfling reported, Bill Gates emphasized the issue of biosecurity and the tremendous risk at hand: “A fast-moving airborne pathogen could kill more than 30 million people in less than a year.” Katz presented an overview of the threat of infectious disease over the past 60 years, during which time the number of new diseases per decade has quadrupled. The number of outbreaks per year has tripled since 1980, with the majority being zoonotic in origin.22

Katz explained that if a disease emerges in one part of the world, it can be anywhere else within 24 to 48 hours due to globalization and the movement of people, animals, and goods. Recent examples of emerging infectious diseases over the past decade include the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in South China; MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia and South Korea; the Ebola outbreak in West Africa; Zika virus in the Americas; the resurgence of polio, particularly in fragile states; the more recent outbreaks of yellow fever; and the ever-present threat of new variants of influenza. She clarified that the threat is not only one of naturally occurring disease,

___________________

22 See http://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2017/02/07/512634375/map-find-out-what-new-viruses-are-emerging-in-your-backyard (accessed September 19, 2017).

NOTE: CO = Country Office; FAO = Food and Agriculture Organization; GHSA = Global Health Security Agenda; HO = home office; IHR = International Health Regulations; JEE = Joint External Evaluation; MoH = Ministry of Health; OIE = World Organ-isation for Animal Health; RO = Regional Office; TWG = Technical Working Group; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCES: Katz presentation, March 9, 2017; reprinted from Update on JEE and Country Planning Post JEE-GHSA Steering Group Meeting, 21 January 2017, see https://www.ghsagenda.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/jee-and-country-planning-post-jee-508.pdf (accessed October 2, 2017).

but also of the ever-present danger of a deliberate event that could have massive consequences. She explained that models demonstrate that such events are possible and maybe even probable within the next 15 years. Modelers also expect a large-scale pandemic every 100 to 150 years, and the 100th anniversary of the 1918 influenza epidemic is approaching. Aside from large-scale potential events, on a day-to-day basis there are biological threats emerging around the world that require functional public health infrastructure to address them. She noted that last year alone, WHO received more than 60,000 reports of biological events, 300 disease alerts identified for follow-up every month, and more than one field investigation carried out each day.

Katz cautioned about the current lack of global preparedness: “There is a very real need for public health infrastructure, but we are unprepared even with the known threat.” She explained that IHR obligates countries to develop certain core capacities to detect, assess, report, and respond to public health emergencies. However, she reported that as of 2012, only 22 percent of countries had fully developed this capacity and by 2014, only 33 percent of countries had (see Figure 3-16).

Several workshop participants further examined the challenges faced in strengthening U.S. efforts in international public health disaster emergency response, as well as sustaining the commitment to GHSA. Hanfling, a practicing emergency physician with 20 years of urban search and rescue response experience with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and FEMA, focused on the critical challenge of coordinating domestic and international emergency response. International disaster response is critically important, emphasized Hanfling: “Despite the milieu in which the discussions occur, we know that delayed response costs lives.” He noted that during World War II, President Roosevelt entered the war only after the attack on Pearl Harbor, at which point millions of lives had already been lost in Europe. Hanfling cited the Ebola outbreak as a recent example of the impact of delay on the ability to galvanize resources, brain power, and expertise that the United States can bring to these discussions.

Marinissen highlighted the challenge of working with U.S. and international partners to strengthen public health preparedness and response at the domestic–international interface: not by working only on domestic preparedness or on international preparedness, but by working on those two together in an integrated way. She explained this coordination will require public health and health systems capacity building around the world and in the United States, as well as preparedness and response planning to enable response with the international community. Regarding FEMA’s National Response Framework23 for how the government organizes itself

___________________

23 See https://www.fema.gov/national-response-framework (accessed August 8, 2017).

NOTE: HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; IHR = International Health Regulations; MERS = Middle East respiratory syndrome; PHEIC = public health emergency of international concern; SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome; WHA = World Health Assembly.

SOURCE: Katz presentation, March 9, 2017.

and integrates community assistance to respond to terrorist attacks, natural disasters, and other catastrophic events, Marinissen noted that international coordination (Annex-Emergency Support Function #8) is still unclear. The U.S. Department of State is briefly discussed as being the lead; however, there is no indication of how it interacts with other agencies, such as HHS and USAID. Kurilla noted that broad processes are in place internationally that are not specific to a particular emerging infectious disease or public health outbreak response. Review processes, cycle times, funding decisions, and so forth are not aligned across different countries, which is an issue that cannot be effectively addressed in the midst of a crisis, when consensus is impossible to reach.

Katz also outlined a set of challenges related to strengthening the U.S. commitment to GHSA. The first pertains to funding: the United States provided a one-time appropriation, but it is not clear if funding will be continued. Even though GHSA is designed to help coordinate efforts, there

are cases of multiple countries funding a single action package in one country, while other countries are neglected. Another challenge relates to where resources are invested, she remarked. The countries receiving capacity-building assistance are not necessarily the same countries or regions that are the most likely to experience an emerging infectious disease, according to hotspot analyses. On the political side, she noted, GHSA is an initiative of the Obama administration. Without knowing the intent of the Trump administration, with some notable exceptions like the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, initiatives that are closely associated with a previous administration are not always necessarily championed by the new administration.

VULNERABLE POPULATIONS AND COMMUNITY RESILIENCE

David Eisenman, director, Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles, defined community resilience as the capacity of the community as a whole to prepare for, respond to, and recover from adverse events. According to theory and research, he explained, strong social and organizational networks are critical for improving resilience, as are examining and strengthening existing resources. He outlined a set of challenges in communicating, training, and scaling community resilience programs. There is often a cultural disconnect between two “tribes”: resilience coalitions that adhere to a collective action and empowerment approach in which the process is paramount, and emergency public health nurses and first responders who feel knowledgeable going into a response but have also witnessed failures of that process first hand. He suggested that if resilience is to be focused on bringing diverse sectors together for collective action, then the public health workforce must be better trained for future responses. Furthermore, he noted that resilience will require public health to find new ways to bring diverse sectors together toward collective action and planning. Another question going forward is whether public health departments can, or will, use a scalable model of community resilience programs that is embedded in the ongoing work in chronic disease, violence prevention, and other areas of day-to-day focus.

Communities directly affected by disasters are not the only ones that benefit from resilience. Redlener highlighted the destination communities that receive evacuees as a neglected dimension: “There is not a single hamlet, town, or city in America that is adequately prepared to deal with the displaced people over a long period of time. They need jobs . . . health care . . . food and water . . . schools. What is happening to the economy in a place where they left and the place to where they are going?” Redlener explained that the experience of evacuation can also be traumatic. He described the logistics of evacuation, especially during the type of spon-

taneous and chaotic evacuation that may occur after a mega-disaster, as “horrendous and overwhelmingly challenging.” For example, many people will evacuate in private vehicles, and people will need to be picked up from within contaminated areas; displaced people must remain where they go for a long period of time. Redlener offered a health care and public health perspective on some of the many challenges faced by evacuees and destination communities:

- Separation from loved ones and dependents;

- Psychological concerns, such as extreme return uncertainty and the end of normalcy;

- Loss of possessions;

- Loss of pets;

- Injuries, such as blunt trauma, radiation, burns, and shock;

- Hunger and thirst;

- Acute evacuation trauma, such as motor vehicle accidents;

- Acute illness, such as myocardial infarction, cerebral vascular accident, and acute respiratory problems;

- Complications of chronic disease: diabetic ketoacidosis, severe hypertension;

- Loss of medication (and critical device) access; and

- Feeling disoriented and terrified.

Vulnerable populations need special, focused attention during a disaster, Redlener explained, characterizing this challenge as the Achilles’ heel(s) of disaster response. He estimated that between one-third to one-half of the U.S. population has some sort of disability. Dan Dodgen, director, Division for At-Risk Individuals, Behavioral Health, and Community Resilience, ASPR, HHS, suggested that to improve individual- and community-level preparedness, the focus should be placed on the people most at risk (although that group can be difficult to define). However, there is an evidential basis for groups most at risk (Brunkard et al., 2008; WHO, 2011; World Bank, 2013). Worldwide, 30 to 50 percent of disaster fatalities are children. During Hurricane Katrina, 50 percent of fatalities were over the age of 75. Women comprised 70 percent of the casualties in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

Abramson described the community system of Gerritsen Beach in Brooklyn, a middle-class neighborhood home to multigenerational families. Most homes sustained major to moderate damage as a result of Hurricane Sandy, and the community was comprehensively damaged. Residents were accustomed to dealing with their own problems and were unprepared for a situation in which an emergency struck all of them at once, leaving them unable to rely on each other. This situation caused increases in mental health

distress and alcoholism, among other consequences. Abramson reflected that “essentially, their problems eluded the systems above them. Nobody was able to see their problems.” He explained how the California wildfires (2007–2008) raised the issue of undocumented immigrants who would not evacuate because they were concerned about losing their jobs or being deported from the United States. Recognition of this problem led to a rapid research CDC grant to identify issues among undocumented immigrants in four cities within 2 months of the H1N1 outbreak. It emerged that the undocumented immigrants were relying on community-based organizations in their communities to help them mediate and broker information. These community-based organizations serving as trusted information brokers were critical to the more isolated or vulnerable communities of undocumented immigrants, he reported. This research also revealed a willingness by undocumented immigrants to engage with certain trusted public officials, particularly around health issues (U.S. physicians and public health officials were particularly trusted).

Abramson summarized findings and lessons learned from a set of tabletop exercises on reaching specific at-risk populations and potentially elusive groups (e.g., urban teens, rural homebound people and their caregivers, people living with HIV, and undocumented Latin American immigrants). Living lab scenarios24 were designed to examine engagement strategies, needs and wants, trusted allies, and potential issues for each elusive group. The exercise revealed that messaging could lead to elusive groups feeling stigmatized. For example, groups with mobility (homebound) or transportation access issues are sensitive to messages that imply an allocation of a scarce resource (i.e., “last in line” syndrome). Groups with stigma or issues regarding disclosure about their condition tend to be sensitive to messages that imply eligibility criteria or patient identification requirements. Abramson stressed that “households are as prepared or as resilient as their weakest and most vulnerable member.” Furthermore, he noted, the exercise revealed that teenagers wanted to be involved and could function as critical fulcrums for families by providing translation, access to new technologies, and information sources. This unanticipated peer influence led to enhanced preparedness. Abramson suggested there could be a useful role for community-based tabletops as a preparedness intervention, and Redlener suggested ways communities might become better prepared to accept individuals who have been forced to evacuate (see Box 3-1).

___________________

24 Abramson discussed three scenarios. Scenario 1: a pandemic outbreak with message directing the population to community-based points of dispensation (subthemes: stigma, disclosure, access); Scenario 2: a toxic gas release with message directing the population to evacuate and register with family reunification systems (subthemes: disclosure, transportation and mobility, trust); Scenario 3: an Ebola-like viral outbreak with message directing the population to isolate and quarantine (subthemes: risk uncertainty, trust, preparedness, informal supports).

Inglesby raised the issue of carrying out preparedness and community resilience work in the environment created around immigrants and refugees in the United States in early 2017, given the reactions to proposed or enacted immigration and security policies. Hanfling called these policies a retrograde step that may force the immigrant community back underground, where they will not seek help in anything other than life-or-death situations. He stressed that these groups—who are not just vulnerable, but disenfranchised—have been put on notice and are at great risk: “I think it is going to be incumbent on us to make sure that we figure out how to reach out and make sure that we have connections into those communities.” Eisenman observed that public health is often perceived as the most trusted agency in government, but most people cannot define public health in practice because “government is government” and the distinction between government and public health is an academic one for most people: “As long as there are problems with trust in government, there will be problems with trust in public health.”

Wynia pointed to the challenge of communicating information to the public about threat, risk, and vulnerability in a compelling way that is neither alarmist nor runs the risk of being dismissed. Alson suggested that the public is tired of hearing “the sky is falling” messaging about potential

disasters that do not actually happen. Abramson warned that city officials often use risk communication as a directive rather than an invitation to a dialogue (e.g., “we will get in touch with you when we need to”). Elise Rowe, ASPR, HHS, highlighted the challenge of combatting negative public perceptions and disenfranchisement with the research community, the preparedness community, and academia.

Hick characterized the current messaging to the public as misleading and offering false assurances about the actual level of preparedness. He argued that the public needs clear messaging to understand the consequences of scaled-back services and the definite and palpable risk of not having response capabilities and systems in place when an incident occurs: “We must radically alter the conversation if we really want to do anything about the problems.”

Alleyne noted the challenge of more effectively translating data for the public to improve the public interface with information. He related an example, from the local health department perspective, of communicating the risks associated with cancer in a community where people were convinced there was a cluster (despite no evidential link) and perceived the government as trying to hide the existence of cancer clusters across the country. He also raised the related issue of how to reach the public with accurate information given the large amount of false and/or misleading information that is circulated. Abramson commented on the powerful role of community systems in shaping everyday lives. There is no single incident commander in a community’s network of systems, but there are many institutions involved: faith communities, civic and fraternal organizations, volunteer fire houses, families, and so forth. He noted that within this network, information passes informally and is richly contextualized by the specific community. Abramson outlined a set of challenges faced by the health and human services systems affecting their ability to respond to community needs: “Can they get there? Do they know where their clients are? Do they know what people need? Is there an effective incident command system [ICS] for health service, and can it acquire the information it needs to ‘direct’ the system?”

Dodgen also commented on the challenge of better integrating the perspectives and needs of the community into emergency response because investment in public engagement activities has had little effect on individual- or community-level preparedness. Dodgen attributed this in part to ongoing challenges of how to successfully engage the entire community, deciding who to bring to the table (e.g., seniors, children, people with disabilities), and how to integrate all perspectives. Mandates, directives, and guidance are confusing and at times conflicting. Various organizations use

different terminology to define subpopulations,25 Dodgen explained, and even defining the concept of a community is challenging. He suggested using a common-sense rule to guide the definition of communities, goods, services, producers, consumers, and community helpers. According to Dodgen, the consequences of failure to integrate the community perspective and needs are lawsuits, bad publicity, and “failing to do our jobs.” However, the consequences of success are resilient, prepared communities and positive health outcomes after a disaster.

___________________

25 For instance, Dodgen gave the following examples of differing terminology. ASPR uses the phrase at-risk individuals; CDC tends to prefer vulnerable populations because it thinks in terms of disease risk; and FEMA has two competing favorite terminologies: whole community and access and functional needs.

This page intentionally left blank.