2

A Brief Overview of Health Security Threats and Programs

Tom Inglesby, director, Center for Health Security, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH), opened the workshop by noting that threats to U.S. health, safety, and security include not only major global and regional epidemics of emerging infectious diseases such as Ebola and Zika, but changes to the ways that known diseases, including dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever, and Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), are spreading throughout the world. Novel pandemic influenzas such as avian influenzas H5N1 and H7N9 are on the rise. The threat of chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) attack is ever present, with sarin and chlorine gas used in terrorist attacks against civilians on a large scale. Inglesby remarked that natural, manmade, and technological disasters pose a serious threat to the nation’s aging, and sometimes archaic, health care and public health infrastructures, as does the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events. These threats are compounded by probable changes to the health care system and a public health system that is chronically under financial stress across the federal, state, and local levels. Uncertainty prevails in key government entities involved in health security, despite the immediacy of the need to prepare for all types of threats.

Citing a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) report of crisis response and disaster resilience, Mitch Stripling, assistant commissioner, Bureau of Agency Preparedness and Response, New York City Health, emphasized that health security is a global problem of “increasing

complexity and decreasing predictability in its operating environment.”1 There are more incidents, new and unfamiliar threats, more information, less time, new players and participants, and exceedingly high public expectations (see Box 2-1). Irwin Redlener, clinical professor, Health Policy and Management and Pediatrics, Columbia University, described how the scale and scope of preparedness not only for disasters, but for mega-disasters, have been inadequate for decades. Mega-disasters are so catastrophically eventful that they overwhelm local and regional capacities to really respond and mitigate their effects. He provided a set of defining criteria for mega-disasters, in descending order of priority: inability to manage immediate rescue of endangered survivors, significant backlog of victims unable to get appropriate medical care or other essential support, inability to protect vital infrastructure or prevent significant property destruction, and any level of societal breakdown or disorder.

To illustrate, Redlener described the consequences of two hypothetical mega-disaster scenarios. If a H5N1-type pandemic avian flu with a 30 percent attack rate occurred in New York City (population 8.2 million), there would likely be a hospitalization rate of 10 percent and a mortality rate among the infected of 2.5 percent. The potential realities of a 6-month flu season for a pandemic of this type would be 2.4 million people sick with

___________________

1Crisis response and disaster resilience 2030: Forging strategic action in an age of uncertainty: Progress report highlighting the 2010–2011 insights of the strategic foresight initiative. For more information, see https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1816-25045-5167/sfi_report_13.jan.2012_final.docx.pdf (accessed August 8, 2017).

avian flu (including 600,000 children) and 60,000 deaths (including 15,000 children) at a rate of more than 300 deaths each day. Hospitals would be overwhelmed by more than 200,000 admissions, and there would be a critical shortage of medical supplies such as vaccines, antiviral medications, hospital beds, ventilators, and other vital supplies. More importantly, he suggested, the cascading consequences would include problems such as schools closing, ill parents, potential quarantines, economic trouble, and little assistance from “the outside.” In the scenario of a 10-kiloton improvised nuclear device detonation in Midtown Manhattan, according to Redlener, there would be 75,000–100,000 immediate fatalities and 300,000–500,000 surviving casualties requiring medical care, but there are less than 60,000 total staffed hospital beds in the entirety of New York state. He explained there are six main potential target cities for this type of attack—Los Angeles and San Francisco, California; Houston, Texas; Chicago, Illinois; New York City, New York; and Washington, District of Columbia—none of which are remotely prepared to deal with an improvised nuclear device. Redlener noted that “the capacity-to-need gap is enormous and insoluble as far we know right now.”

Much work had been done in the areas of health security over the preceding 15 years, remarked Inglesby. The efforts have enabled many communities around the country to become more capable of caring for victims of more “normal” or anticipated disasters within some bounds. Inglesby noted that any health care system would be hard pressed to care for anything beyond a handful of highly contagious patients during a lethal epidemic or to care for large numbers of patients following major disasters. The goal should be to build health care and public health systems’ capacity to care for and manage tens of thousands (or more) injured or infected people needing medical care during epidemics and catastrophes, remarked Inglesby.

Inglesby commented that to some extent, within the United States a national public health system that facilitates early detection of biological threats, controls epidemics, and responds to disasters has been built over many years. The United States and the world relies on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during new epidemics (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome, H1N1, Ebola, and Zika). The United States relies on state and local public health officials for top-level scientific analysis and expertise on infectious diseases, surveillance programs and warning of new outbreaks, laboratory testing and safety, communicating risks to the public, medicine stockpiles, and community response programs, among others. At the state level, Inglesby remarked, capacity for preparedness and response is variable. In 2016, the National Health Security Preparedness

Index2 revealed a national preparedness level ranking of 6.8 out of 10. This recent score demonstrates that although there is capacity in the system, there is plenty of room for improvement. Despite its crucial role, public health is chronically underfunded and lacks the resources for people and technology necessary to succeed, Inglesby remarked. In contrast, foundations are supporting public health like never before, and high numbers of young people are pursuing careers in public health (Leider et al., 2015; Prina, 2017).

According to Inglesby, the United States has the most impressive national ability to make new medical therapies, vaccines, and rapid diagnostics, including research and development for medical countermeasures (MCMs) for biological threats, antimicrobial resistance, pandemic flu, emerging diseases, and CBRN challenges. He attributed this ability to the efforts of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), CDC, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) on the risk side, as well as universities and biopharmaceutical companies on the research and development side. He noted that the United States and much of the world has relied on this system to make MCMs during various past crises, including outbreaks such as 2001 anthrax, H5N1 bird flu, 2009 H1N1, the Ebola virus outbreak from 2013 to 2015, the ongoing Zika virus outbreak that started in 2015, and others. He described the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, an alliance to finance and coordinate the development of new vaccines to prevent and contain infectious disease epidemics, as a welcome development but noted that the development process still takes too long to make a difference during the most important period of a new outbreak. Flu is the best-case scenario, but in the past it has taken as long as 6 months after the discovery of a new flu pandemic for this system to produce an effective vaccine. For entirely novel threats, it can take a decade or longer, if at all, to develop new medicines and vaccines, unless the development process is already far along due to other reasons. Inglesby suggested aiming to achieve the goal set forth in the November 2016 President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology report,3 which called for the U.S. government to develop the national capacity (over the next 10 to 20 years) to make a new vaccine or medicine for any new biological threat within 6 months.

___________________

2 See http://nhspi.org (accessed June 27, 2017).

3 President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology report, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/PCAST/pcast_biodefense_letter_report_final.pdf (accessed August 8, 2017).

A plethora of powerful new biotechnologies and transformative tools is on the horizon, according to Inglesby, with the potential to enormously benefit medicine, science, industry, and agriculture. Clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeats and their associated systems for editing, regulating, and targeting genomes is only one of the most visible tools emerging, and countries around the world are making billion-dollar investments. While we scan the horizon for new technologies and approaches to help prepare for new threats, he cautioned about the need to react wisely to potential adverse consequences biotechnologies will bring, such as novel, highly lethal, highly transmissible viruses that do not exist in nature. He suggested establishing international biosafety norms for laboratory work that has the potential to cause epidemics or great harm following accidental or deliberate laboratory release.

Maintaining norms against chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons through treaties and other means is more critical than ever, emphasized Inglesby, hence the importance of strengthening international health security to protect the United States and other countries and preventing the proliferation and use of chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. Continued work on the international front to help contain outbreaks of infectious diseases outside of the United States is also critical, not only for reasons of ethics and expertise, but to prevent the spread of epidemics to the United States. As noted by Umair Shah, executive director of Harris County Public Health, global health security is essential to U.S. national security. The International Health Regulations (IHR) developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2005 have established the norm that countries must be prepared to manage outbreaks of international importance, but only a small subset of countries is prepared to achieve this independently despite their commitment to IHR. The Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) enlists talent and resources in many participating countries to help build a national-level epidemic response. The United States should continue to support and build on the progress of the GHSA, urged Inglesby.

Inglesby commented that many entities from both the public and private sectors have driving and supporting roles in U.S. health security. These include ASPR’s Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP), BARDA, and the Healthcare and Public Health Sector Critical Infrastructure Protection (CIP) Program; DHS’s Office of Health Affairs National Biosurveillance Integration Center and BioWatch; the National Disaster Medical System; CDC’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) Program; FDA; NIH; DoD; the Medical Reserve Corps (MRC); nongovernmental organizations, such as Healthcare Ready, the National Association of County & City Health Officials (NACCHO), the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, the Council on State and Territorial Epidemiologists, the Association of Public Health Laboratories, the National Association of Chain Drug

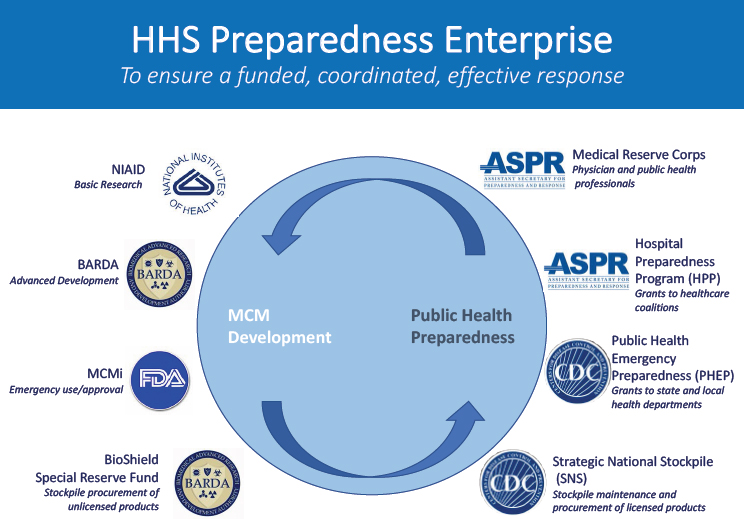

NOTE: ASPR = Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response; BARDA = Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; MCMi = Medical Countermeasures Initiative; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCES: Hanen presentation, March 9, 2017; East End Group (eastendgrp.com).

Stores, and the American Red Cross; and local and state health departments, health care coalitions, and private health care system programs serving communities throughout the nation.

Laura Hanen, chief, Government Affairs, NACCHO, provided an overview of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Preparedness Enterprise, which aims to ensure a funded, coordinated, effective response to health threats across many of these entities (see Figure 2-1).

Maria Julia Marinissen, director, Division of International Health Security, Office of Policy and Planning, ASPR, HHS, described how the 2006 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act and 2013 Reauthorization Act created and established ASPR leadership in national and international preparedness and response initiatives and activities. Other duties required by ASPR include providing personnel, countermeasures, coordination, and logistics surrounding disaster response. HHS leads federal public health

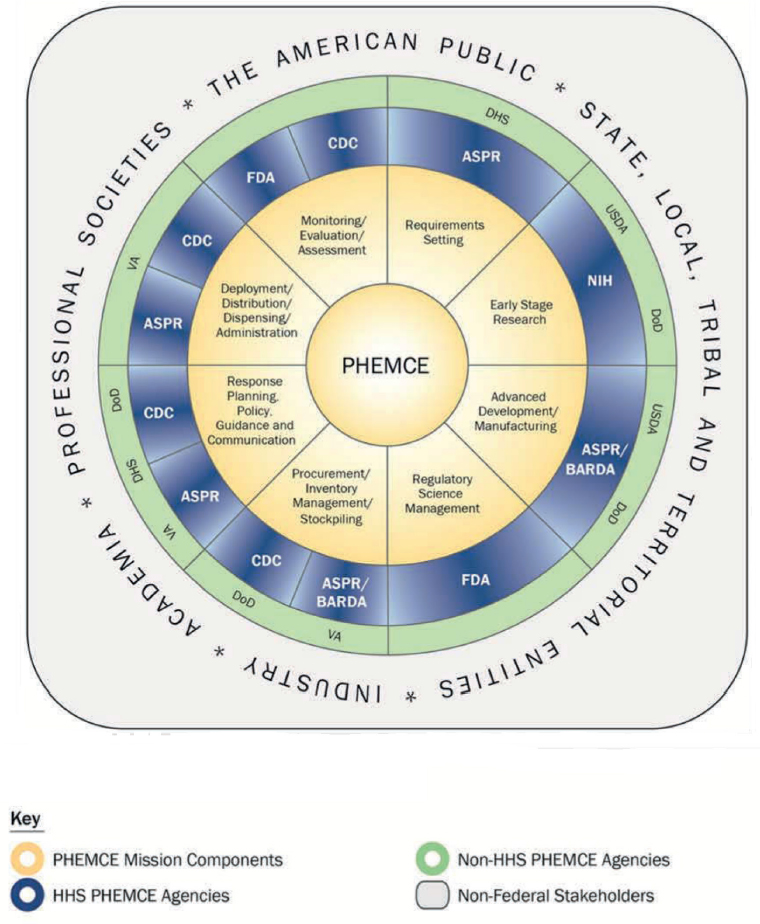

NOTE: ASPR = Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response; BARDA = Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DHS = U.S. Department of Homeland Security; DoD = U.S. Department of Defense; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; NIH = National Institutes of Health; PHEMCE = Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture; VA = U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

SOURCES: Hu-Primmer presentation, March 8, 2017; ASPR, 2017.

and medical response to public health emergencies and National Response Framework incidents (Emergency Support Function #8).

Jean Hu-Primmer, senior advisor, CBRN and Pandemic Influenza, FDA, explained that the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise (PHEMCE) is also led by ASPR and comprises HHS entities such as FDA, NIH, BARDA, and CDC. PHEMCE coordinates with DoD, DHS, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and state and local public health officials, as well as hospitals, clinical networks, and medical product manufacturers in the private sector to advance the nation’s capacity for public health response (see Figure 2-2).