4

Underlying Issues in Health Security

Challenges can hinder all facets of the tightly interrelated and codependent health care and public health sector, and a lack of resilience in one part places an added burden on the sector as a whole. The following sections examine the participants’ discussions about an overarching set of issues that pervade the sphere of health security, from an overreliance on response strategies to a lack of understanding and awareness by those with authority. Understanding the challenges can enhance the health care and public health sector’s ability to prepare, respond, and recover.

ADAPTIVE AND TECHNICAL CHALLENGES

Runnels drew a distinction between the adaptive and technical aspects of such challenges. Challenges that are more technical in nature tend to have problems and solutions that are relatively clear and easily defined; the path from point A to point B is understood, albeit not necessarily easy to traverse. She explained that adaptive issues may be difficult to define and have solutions that are not necessarily clear; the path from point A to point B is uncertain. Adaptive challenges often emerge from stakeholders’ values, loyalties, and what they stand to lose if the status quo changes. Runnels reflected: “What if the adaptive problem is stemming from ourselves as a group? What can we do to challenge our deeply rooted beliefs? We are really comfortable being the solution finders and putting out fires, but maybe that is not the best place to spend our energy.”

MULTIPLE AND COMPLEX SYSTEMS

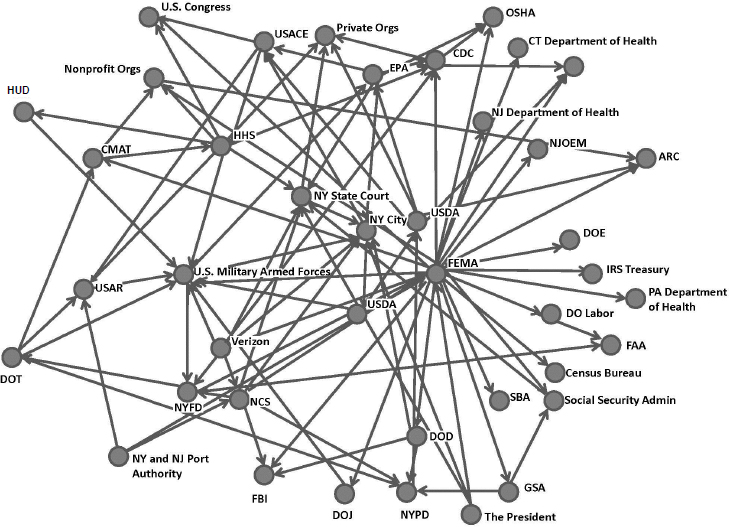

Abramson explained that every disaster response involves the activation of several complex systems: emergency management and response systems, health and human services systems, and community and kinship systems. Each of those systems has its own rules, its own structures, and its own dynamics. Figure 4-1 illustrates the complexity of the network of systems activated during the September 11, 2001, emergency response.

Abramson explained that within each of these three systems, there are variable degrees of two integral components: structured information and community context. The emergency management and response systems have the most structured information and the least amount of community context, while the community and kinship systems have the least amount of structured information and the greatest amount of community context. He described the health and human services systems as falling somewhere in the middle, but the dynamics within this system are often unclear. He illustrated this point with the example of New York City after Hurricane Sandy. Hospitals transferred particular patient populations into the communities, which created a surge for the home health and visiting nurse systems. As a result, other patients with complex treatment regimens (e.g., renal dialysis, HIV/AIDS, end-stage renal disease, methadone maintenance treatment programs) could no longer access their ambulatory care clinics. He highlighted the “last mile” problem of connecting and integrating the emergency system, the health and human services system, and the community and kinship system as a critical challenge going forward.

Kurilla also commented on the adaptive nature of integrating an entirely new conceptual strategy for approaching a problem into these existing systems (i.e., changing the rules) when the status quo is to focus on incremental change toward faster and less expensive solutions. During a response, “usually in the midst of a crisis, we’ll pay for it, but in the absence of a crisis, usually the cheaper has to dominate, and so we sort of shortchange that intercrisis period, which hobbles our ability to be prepared.”

According to Kurilla, finding ways to coordinate and collaborate effectively with sectors of government that may not have emergency response in their bailiwick can be problematic when such sectors are given a very specific task that is independent of the need to either be fast or slow depending on the external situation, because from their perspectives, the requirements and expectations do not change. To illustrate, he explained that the mission of human resources is specifically to maintain and ensure the integrity of the hiring process. If there are any irregularities, human resources will be blamed, but if there are no irregularities, they get no credit. If Congress provides a large supplement to address a problem, and a wide array of contract actions must be instituted but a future investigation reveals a minor

NOTES: Based on FEMA situation report requests during September 11, 2001, response. ARC = American Red Cross; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMAT = Crash Mapping Analysis Tool; CT = Connecticut; DO Labor = U.S. Department of Labor; DOD = U.S. Department of Defense; DOE = U.S. Department of Energy; DOJ = U.S. Department of Justice; DOT = U.S. Department of Transportation; EPA = U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; FAA = Federal Aviation Administration; FBI = Federal Bureau of Investigation; FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency; GSA = General Services Administration; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; HUD = U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; IRS = Internal Revenue Service; NCS = National ComNet Services; NJ = New Jersey; NJOEM = New Jersey Office of Emergency Management; NY = New York; NYFD = New York Fire Department; NYPD = New York Police Department; OSHA = Occupational Safety and Health Administration; PA = Pennsylvania; SBA = U.S. Small Business Administration; USACE = U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; USAR = U.S. Army Reserve; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

SOURCES: Abramson presentation, March 8, 2017; Kapucu, 2005.

irregularity, those in charge of the contracts will be called to task despite being pushed by outside forces to institute the contracts quickly. Kurilla reported that he has put recent efforts into arguing that preparedness should be considered a bona fide need that is the criteria for justifying contracts.

COMPETING PRIORITIES AND PERCEPTIONS

Lori Peek, author, Children of Katrina, and director, Natural Hazards Center and Professor of Sociology, University of Colorado, discussed the challenge of incentivizing problem solving for issues such as critical infrastructure protection between disasters. Hanfling reflected that this issue might be due to the competing calculus for identifying priorities in critical infrastructure protection: an emergency manager may think about critical infrastructure protection as strengthening buildings and hard space, while an emergency physician may think about it as breaking down those walls to provide access to care. Hanfling suggested that the challenge is brokering that calculus between many competing priorities. Andrew Pavia, University of Utah, also highlighted the absence of a system for prioritizing and coordinating infrastructure protection efforts. For example, in some areas community hospitals would likely bear the brunt of maintaining critical infrastructure in a disaster, but they have not invested in preparing because they do not perceive themselves as indispensable like larger hub facilities that have made investments in protection. Hick commented that getting communities to value critical infrastructure protection will be important in addressing this challenge and incentivizing interim preparation.

Abramson cautioned that other sectors may erroneously perceive the public good as a zero-sum game, giving rise to collaboration problems. For example, he noted that the 58 city hospitals in New York City have competing interests that engender unwillingness and tension in trying to collaborate. Alson noted that state- and local-level agencies have their own sets of competing priorities that often are their first concern and obfuscate the broader picture of what needs to be achieved.

DIFFICULTY DEFINING GOALS AND INTERPRETING PROGRESS

Redlener identified the “denominator problem” as determining what is needed versus what has been done. He suggested that if preparedness is a spectrum between 0 percent prepared (the starting state) to 100 percent prepared (which is impossible), within that spectrum falls both the current state of readiness and an ideal realistic state of readiness, with the latter determined by the local context for defining preparedness. The challenge is how to interpret the change (delta) between the starting state and the current state. The typical interpretation—“we are doing fine because we’re

making progress”—is much more problematic, he argued, than the interpretation that things are behind where they ought to be: “We must understand where we are going, how we are going to get there, and be honest about where we are.”

Measures of success also vary across sectors, remarked Brinsfield. Other sectors measure success objectively (e.g., what can be produced). Public health and health care, she noted, tend to measure success by “whether we are doing the most we can with the money we have, or whether we are successfully moving forward,” rather than objectively assessing the potential outcomes of different available strategies prior to implementing a plan of action.

LACK OF RESOURCES TO SUPPORT DATA-DRIVEN IMPROVEMENT

Runnels noted that people respond reactively to many disasters and questioned why there is a lack of upfront investment in preparedness and resilience. Hick highlighted two fundamental reasons for critical infrastructure protection: cost and time. Identifying the deficits requires a dedicated analysis of all components that contribute to the whole. Once the deficits are identified, Hick noted that a compelling case must be built to convince an institution to address them (especially in an older institution that requires costly retrofits), with clear arguments to establish the cost of inaction for employee safety, patient safety, public safety, and the economy.

As Wolf noted, the threat to a community is constantly evolving during an emergency, which gives rise to many challenges about how to collect, validate, and disseminate data on risk and threat information, as well as prioritizing and measuring mitigation efforts. Margaret L. Brandeau, professor of management science and engineering and medicine, Stanford University, explained that processing risk and threat information requires gathering information from multiple sources, determining the risk and level of uncertainty, and then disseminating information about risks and actions that can be taken to mitigate risk. Brinsfield suggested that the challenge will be developing a true understanding of how to carry out meaningful, continually updated risk and threat assessments in the bio space. W. Craig Vanderwagen, co-founder and director, East West Protection, LLC, also noted the ongoing challenge of understanding and mitigating not only hazards, but vulnerabilities.

OVERRELIANCE ON RESPONSE STRATEGIES

Kurilla pointed out that a clear-cut distinction between response and preparedness is not often well articulated by practitioners. As a result, the

development of the field has focused primarily on response and less so on preparedness, even though, as Brinsfield emphasized, prevention is the ultimate public health preparedness. According to Sally Phillips, deputy assistant secretary for policy, ASPR, HHS, the disproportionate focus on response was born of necessity. She remarked that the lack of an evidence base makes it difficult to disseminate and integrate response and preparedness into proactive policy and planning. Redlener further commented that preparedness is context specific, meaning different things for a city, hospital, health system, or a nation. Therefore, Redlener noted, a foundational gap, particularly for governments, is precisely defining preparedness in order to establish goals, benchmarks, and budgets.

This disconnect exists in part because of the firm belief in the field that each disaster or public health emergency is unique, even though emergencies and disasters are often subsumed under the same category, as noted by Stephen C. Redd, rear admiral, U.S. Public Health Service, and director, Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, CDC, HHS. Brandeau explained how the characteristics of disasters vary widely along multiple dimensions. Timelines for emergencies can range from hours or days (e.g., an explosion in a fertilizer plant) to weeks or months (e.g., an Anthrax letter) to months or years (e.g., Zika virus). The level of uncertainty varies as well, she noted. For example, in the case of Hurricane Katrina, the appropriate response to people’s needs was fairly well understood, but the Ebola outbreak presented much more uncertainty. The affected population may vary from specific people (e.g., in a flood) to specific groups (e.g., pregnant women for the Zika virus) to everyone (e.g., some sort of infectious disease outbreak). She also explained that during any public health emergency, information develops over time, in different places, and comes from different domestic and international sources (e.g., CDC, state, county, city, public health departments, and clinicians).

Redd commented that different emergencies require different types of preparation—a natural weather disaster versus the Zika virus outbreak, for example—although the structures for those responses might be similar. Although some fundamental capabilities are already in place, Redd remarked that there is still much work to be done to prepare for different categories of emergencies. He described three broad categories: predictable emergencies that will definitely happen (e.g., hurricanes and earthquakes), predicted emergencies of high consequence that may never happen (e.g., anthrax attack) but require “very exquisite readiness to be able to respond almost instantaneously,” and emerging events (e.g., Ebola and Zika virus outbreaks).

Several attendees provided examples of how current policies, rules, and guidance do not support the behaviors and practices needed to improve health care and public health preparedness, response, and recovery. Hick

commented that there is an existing wealth of information in the public sector from regulatory and standards organizations relating to continuity of operations and critical infrastructure protection;1 however, they lack sufficient specificity. Hick argued that these requirements are completely inadequate to enable facilities to appropriately mitigate risk. To illustrate, he quoted the entirety of the language from the National Fire Protection Association’s Standard on Disaster/Emergency Management and Business Continuity/Continuity of Operations (NFPA 1600) on mitigation:

- The entity shall develop and implement a mitigation strategy that includes measures to be taken to limit or control the consequences, extent, or severity of an incident that cannot be prevented.

- The mitigation strategy shall be based on the results of hazard identification and risk assessment, an analysis of impacts, program constraints, operational experience, and cost–benefit analysis.

- The mitigation strategy shall include interim and long-term actions to reduce vulnerabilities.

Stripling noted that legal barriers prevent effective leveraging and information sharing in many communities due to fears of litigation and possible admissions of guilt. He provided the example that the emergency management system is based on the DHS apparatus, which treats all documents as secure documents. Local entities are often uncertain what types of information must be shared based on those legal frameworks without risk of liability. Current guidance emphasizes sharing with health care partners, but lawyers often instruct them not to share, which causes continual conflict.

Anthony Barone, founder and principal advisor, Northern Virginia Emergility, LLC, noted that investigation and intelligence data are rarely used in ICS at the local and state levels. However, he reported that there is an explicit section on ICS in the National Incident Management System Intelligence/Investigations Function Guidance and Field Operations Guide, published by FEMA, which describes how and where to integrate research, response, and incident command; it contains explicit mention of where research, epidemiology, and complex biological chemical incidence could fit into ICS.

___________________

1 FEMA PS – PREP; NFPA 1600; ISO 22301; ANSI/ASIS Spc.1-2009; TJC/DNV; HHS – sector CIP lead (RIST and THAM).

LACK OF UNDERSTANDING AND AWARENESS BY THOSE WITH AUTHORITY

Communicating effectively with the people making major decisions about health care and public health preparedness, response, and recovery is a major challenge, according to Alleyne:

Public health decisions are not necessarily being made by public health professionals or emergency preparedness professionals, which is why there is not a great preponderance of support for developing these critical infrastructures or supporting them at the local level. Decisions are being made by business professionals often focused on the bottom line, who do not value the same rationales for preparedness that health professionals do.

Many policy makers do not understand the difference between public health and health system preparedness, said Hanen, and they require basic education on the entire enterprise, its component parts, agencies’ responsibilities, and funding streams. Wolf remarked that the C-suite of the private sector has a vastly different paradigm for communicating, relying heavily on data to explain what needs to be done and why it needs to be done.

LACK OF INSTITUTIONAL MEMORY AND LONG-TERM CONNECTIVITY

Lien noted that there is a lack of institutional memory within the preparedness arena, partly driven by the annual funding cycle at the local and state levels, as well as a large amount of workforce turnover. She posited that the lack of historical knowledge and institutional relationships is a barrier to effective leveraging and requires rethinking of the same problems time and again. She also noted that practitioners lack resources and time to digest what was learned and translate it into action that can sufficiently tackle all the pieces of these problems.

RELIANCE ON ACTIVATION OF REDUNDANT SYSTEMS

Hick cautioned that activating continuity of operations and resiliency plans inherently creates risk, because redundant systems are rarely as good as native ones. He stressed the importance of determining with specificity the appropriate thresholds for risk,2 cost, and delays within the system. For instance, privacy concerns can create delays in sharing life-saving information about a patient (see Box 4-1). Specificity poses a challenge in determining those thresholds, however, because it comes at the price of time, cost, and remediation to the facility. He also cautioned that the right

___________________

2 For example, a once in a 10-, 100-, or 1,000-year event.

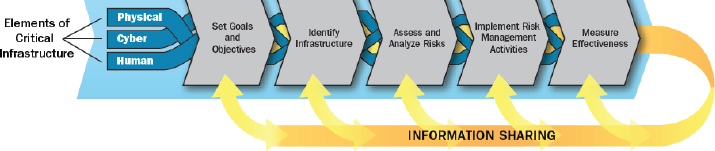

risk threshold for today is not necessarily the right threshold for tomorrow, given the increasing trend of billion-dollar climate disasters. Determining reasonable thresholds may require outside expertise (such as tiger teams to challenge the infrastructure) that may be costly, but can provide valuable external perspective on the system. He illustrated this point with a flowchart for risk preparedness (see Figure 4-2).

SOURCES: Hick presentation, March 8, 2017; National Infrastructure Protection Plan, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/national-infrastructure-protection-plan-2013-508.pdf (accessed August 8, 2017).

Wynia observed that people doing public health work are often so committed and devoted to the mission of helping people that they become “martyrs to the system,” absorbing funding cuts and continuing to operate without pushing back. He suggested that from an ethical perspective, there is value to that martyrdom, but from another perspective, it is enabling: “There is a critical intersection between personal devotion and resilience and enabling organizational malfeasance and bad decisions to continue.” Runnels described this tension as arising in part from an “us versus them” mentality and suggested that resolving it will require striking a balance between the mission-driven work in public health and a broader system that has different drivers. Hick commented that the public health sector has historically continued to function, in whatever way possible, in the face of significantly scaled-back resources, but the public needs clear messaging to understand the consequences that scaling back entails.