2

Context for Science-Engagement Activities

“I was surprised by the advanced state of stem cell research in Iran”

– American neuroscientist, 2012.

Since the turn of the century, hundreds of Iranian and American scientists have worked together—in their laboratories, in the field, through electronic correspondence, and during international conferences and related events. The enactment in Washington of the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act of 1994, subsequent sanctions-oriented legislation, internal security precautions by both countries, and lack of financial support have continuously complicated cooperation. Nevertheless, determined scientists from the two countries have found ways to collaborate, at times during side-by-side meetings based on personal initiatives that have led to jointly authored scientific papers.

A primary objective of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) in embarking on a science-engagement program with Iranian organizations in 2000 was to help increase professional contacts, which would benefit American and Iranian participants, their institutions, and the international science community more broadly. Iran had developed significant science, engineering, technology, and medical capabilities in a number of fields of regional and global interest. However, in a variety of ways the Iranian scientific community had been isolated from the mainstream of international science; and many Iranian achievements were not well known beyond the borders of the country.1

___________________

1 Glenn E. Schweitzer: U.S.-Iran Engagement in Science, Engineering, and Health (2000-2009): Opportunities, Constraints, and Impacts, The National Academies Press, 2010, p. 2.

As the science-engagement program developed, many scientists and a number of government officials in the two countries became convinced that bilateral activities sponsored by the National Academies and by other U.S. organizations, in cooperation with Iranian counterparts, could lead to the evolution of important personal and institutional relationships. These connections would contribute to the development of a less adversarial relationship between the two governments. They argued that building and demonstrating trust between American and Iranian scientists could help soften negative attitudes of some government officials in both capitals about the dangers associated with cooperation on politically important issues. But such confidence-building usually requires a long and sustained process.

In 2010, the National Academies review of a decade of U.S.-Iran engagement in science, engineering, and medicine included the following observation on attitudes in Iran concerning science-engagement with American institutions.

Some forces in Iran would welcome a termination of engagement programs involving the United States, including engagement in science. At the same time, given Iran’s long-standing commitment to excellence in science, it is difficult for even advocates of termination who live in Iran or elsewhere to ignore the wellspring of technology in the United States. Nor have powerful isolation-oriented voices succeeded in suppressing the views of others who believe that scientific cooperation is essential if Iran is to graduate from being viewed as a developing country and join the ranks of the industrialized countries in the foreseeable future.2

In the United States, much of the early enthusiasm for science-engagement had declined by 2010, in view of the uncertainties and difficulties in carrying out rewarding exchanges within the downward spiral of the bilateral political relationship between the two governments. However, as noted in Chapter 1, the National Academies decided to revive their program after a temporary pause in carrying out cooperative activities. Even though it became increasingly difficult to bring important specialists from the two countries together, both the Department of State (the department) and the National Academies considered continuation of the program to be important.3

___________________

2 Ibid, p. 68.

3 Meeting with Deputy Secretary of State, Nov. 15, 2009.

By 2010, a small cadre of influential enthusiasts interested in the program of the National Academies was in place in each country. Some proponents of exchanges at various universities and research centers in the two countries were pleased with the results that had been achieved and wanted to continue activities on the same tracks. Others were planning to expand activities, while also focusing on the topics that they previously had explored. A few scientists in the two countries urged consideration of fresh topics and new modalities in moving forward.

This chapter now turns to a brief overview of the National Academies-supported program activities from 2000 to 2009. Then a summary of the continuing evolution of Iran’s science and technology infrastructure that provided the framework for engagement is presented. Intimately linked to the interests of the Iranian government in international engagement in science has been the evolution of the government’s policy in striving for a knowledge-based economy, which is highlighted. The continued expansion of educational opportunities and research activities in selected fields and the effort to expand the number of technology-oriented companies despite economic constraints are discussed since they reflect important Iranian commitments that should be taken into account in designing the National Academies’ strategy for engaging Iran in ways that are mutually beneficial. Finally, the ingenuity and experience of Iran in coping with economic difficulties, including sanctions over many decades, are added to the array of topics of relevance to the future of science-engagement.

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES’ INITIAL PROGRAM ACTIVITIES (2000 TO 2009)4

During the first decade of science-engagement, the National Academies, in cooperation with partner organizations in the United States and Iran, organized 17 workshops, with each workshop usually involving 25-30 specialists from the two countries. Almost all workshop participants were active in the specific fields of science, engineering, or health being considered. From the beginning of engagement, workshops have been the primary mechanism for initiating and at times continuing cooperation.

With few exceptions, each participant in the workshops made a presentation on an important aspect of the topic of interest; and each presentation was then considered for publication in a Proceedings of the workshop pre-

___________________

4 Schweitzer, op. cit., p. 15.

pared by the National Academies, an American partner organization selected by the National Academies, or an Iranian organization. This requirement underscored that only qualified scientists could participate in the activity and ensured that the Iranian and American participants would have written records of the scientific achievements that were considered sufficiently important to be included on the workshop agenda. These proceedings have been important documents in highlighting serious research efforts in Iran and the United States. In some cases, the proceedings are the only readily available records of significant Iranian research achievements.

The topics of workshops through 2009 can be clustered as indicated below.

- Food-Borne Diseases (2)

- Effective Use of Water Resources (3)

- Earthquake Science and Engineering (2)

- Science, Ethics, and Appropriate Use of Technology (2)

- Science and Society (2)

- Preventing and Responding to Crises (2)

- Ecology and Energy (2)

- Higher Education and Research Challenges (2)

Additional engagement activities through 2009 included the following:

- Individual exchanges in both directions involving a total of 25 travelers.

- Six joint planning meetings in Iran, the United States, and third countries.

- Visits to Iran by four American Nobel Laureates.

- A group visit to Iran by seven U.S. university presidents.

- A four-year pilot project in Iran on food-borne disease surveillance and response.

Engagement activities have always been complicated to arrange. Workshops held abroad usually have taken 12-18 months to organize, despite pressures to show near-term results. During the early years of engagement, more than a dozen planned events were cancelled; and many more were postponed. Occasionally, unexpected political concerns arose; but administrative issues were more frequently the reason for delays or cancellations.

Representatives of the two governments usually continued to express support for delayed programs. Obtaining visas on time, processing license applications in accordance with U.S. requirements, and arranging for the presence at events of both key scientific leaders and early-career researchers were sometimes difficult. Additionally, financial support for engagement activities was often uncertain; and almost all activities depended to an extent on a number of scientists contributing considerable personal time and even personal financial resources to ensure success.

The original plan of the National Academies called for individual exchanges to become a major component of the program. However, few Americans were interested in visiting Iran alone; and usually they traveled in groups of two or more. In general, American scientists were interested in not only participating in a workshop on a scientific topic in Iran but also adding side visits to their workshop program. This pattern quickly developed as the most common approach.

Also, the American travelers quickly learned that there were few sources of funds available for follow-on activities. This reality dampened enthusiasm for developing partnerships that depended on personal initiatives to raise financial resources for sustaining relationships.

Meanwhile, many Iranian scientists seemed more comfortable traveling alone to the United States, particularly if they had opportunities to visit relatives or friends in addition to exploring new scientific challenges. They frequently combined the two purposes of their travel. This approach was usually successful.

As the engagement program developed, interest of the leaders of the academies and of prominent politicians in the two countries increased. During the early period of the National Academies’ program, three Presidents of the National Academies visited Iran at the invitation of the Iranian Academy of Sciences and of a leading medical university. The President of the Academy of Sciences of Iran visited the United States on three occasions. During one of his visits he presented a medal to the President of the National Academy of Engineering in recognition of his American colleague’s support of cooperation between the two countries. Also, former President of Iran, Mohammed Khatami, visited the National Academies following completion of his term in office; and he led a lively dinner discussion concerning the intersection of engagement with political concerns. Shortly after his visit to the National Academies, he was the keynote speaker at an inter-academy workshop in Tehran titled Science as a Gateway to Understanding.

In 2009, the National Academies’ staff recorded the following observations as to accomplishments and impressions during a decade of science-engagement.

Personal testimonials about the importance of science exchanges are common. A well-known American water expert considered that his visit to Iran was the highlight of his long professional career. An e-mail from a brilliant young Iranian microbiologist stated that her just-completed visit to the United States was helping her focus her research interests. An American science-policy analyst cannot wait to return to Iran for his third visit where he will obtain further information about the difficulties of shaping policies in a scientifically advancing and rapidly changing country.

But the number of U.S.-Iran exchanges is now very small—three to four significant events each year in addition to the occasional individual visitors driven by professional interests and not simply by family ties. There should be opportunities for dozens of exchanges sponsored by a number of U.S. universities and nongovernmental organizations as was the case in earlier years. Obtaining U.S. visas is a major impediment for Iranians hoping to travel to the United States—for study, for conferences, or simply for the cultural experience. Also, it is not surprising that Americans are apprehensive about traveling to Iran, which is portrayed by the U.S. media as a dangerous country.

Politics is on the agendas of a large segment of the Iranian population. Relatively few Americans spend much time thinking about developments in Iran and that nation’s policies. Meanwhile, many Iranian leaders of all stripes within and outside the government spend a considerable amount of their time discussing U.S. policies.

During the initial period of cooperation, the National Academies did not attempt to adhere to a master list of priorities in terms of topics, methods of cooperation, or types of projects, although priority interests were a frequent topic of discussion between the scientific leaders and their supporting staffs of the two countries. The activities were difficult to arrange, and ease of implementation was an important criterion in moving forward with a proposal of mutual interest when selecting projects to be supported. Nevertheless, each project that was undertaken addressed issues of professional scientific

interest to participants from both countries, with a reasonable chance of full implementation and sustainability.

Unfortunately, as previously noted, a number of promising proposals developed by the National Academies were not included in cooperative activities for a variety of reasons. The difficulties included shortage of funds available for implementation (a primary constraint), lack of support by one or both governments, and highly publicized political concerns that arose at critical stages of the planning process, which discouraged proponents in the United States and in Iran from moving forward.

From the outset of the program, the National Academies frequently consulted with the U.S. government on the status of similar activities since governmental endorsement was essential to obtain visas for visitors and important to ensure compliance with government requirements. Of particular concern was uncertainty as to the need for licenses from the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the Department of the Treasury. These consultations were also an important mechanism in staying abreast of related activities of other organizations and in ensuring that the National Academies’ activities and program results would be brought to the attention of both key policy officials in the U.S. government and leaders of other organizations with related interests.

In addition, the National Academies played an important role in serving as an unofficial interlocutor between the department and other interested nongovernmental scientific organizations in the United States. Among the issues of broad concern were the changing political constraints in Washington and Tehran on exchanges, developments concerning personal safety of American travelers, and occasionally new funding opportunities to support exchanges. While the National Academies’ science-exchange program was small, it was larger than other science-exchange programs being carried out at the time. Therefore, consultations of the National Academies with the department were of interest to other institutions, which had fewer opportunities for such discussions.

The National Academies’ programs almost always involved American specialists from a number of U.S. universities, research centers, and other organizations. Thus, the National Academies became an important mechanism for informing many organizations interested in exchanges about developments in Washington.

THE VISION AND SUBSEQUENT ACTIONS TOWARD A KNOWLEDGE-BASED ECONOMY IN IRAN

A significant aspect of designing and implementing exchange programs that has been and should continue to be of interest to American scientists is a general understanding of the organization, policies, and programs of the many elements of the Iranian science and technology enterprise. To this end, a brief discussion of the evolving policy and institutional framework for carrying out research, higher educational, and high-tech innovation activities in Iran is presented below. Also, pointers to additional information in this area are set forth, while recognizing that considerable information is available on the many English-language websites established and regularly updated by hundreds of relevant Iranian organizations, and particularly public sector organizations.

By the early 2000s, government leaders of Iran had become impatient with the rate of progress in attaining international recognition for Iran’s science and technology (S&T) wherewithal, particularly in raising the low global rankings of its universities. In 2005, the government released a 20-year Vision for development of Iran’s economy and the associated S&T capabilities that would strengthen the technical prowess and reputation of the country at home and abroad. At about the same time, a new economic development plan that reflected many of the policies set forth in the Vision was released. The government’s declarations called for Iran to attain first

place in the region with regard to economic, scientific, and technological capabilities based on the five principles set forth in Box 2-1.

The Vision challenged the concept prevalent in some areas of the Moslem world that science is subordinate to theology. Rather, the document suggested that rationality should be based on scientific evidence.

The economic importance of an improved approach to research as advocated in the Vision was quite significant due to adverse trends in Iran at the time, including the following:

- Loss of Iranian expertise to countries with better developed infrastructures for research and innovation.

- Unemployment that resulted in university graduates driving taxis in order to support their families.

- Inadequate and dwindling water supplies with serious adverse impacts in (a) expanding modern agriculture practices, and (b) providing clean drinking water for both urban and rural populations.

- Excessive dependence on oil exports to generate income needed for imports of consumer and capital goods.

- Population growth and city/rural inequities, with wealthy residents increasingly separated economically from the general population.

- Inadequate investments in future development of energy and mineral resources while depletion of non-renewable resources continued.

- Introverted and inflexible economic structures that stifled innovation.

- Inadequate regional and global integration that lead to wastes of resources in competition with other countries.

- Inadequate participation of women in the work force.5

The 20-year Vision focused on policies and concerns at the highest level of government. At the same time, many organizations in Iran had their own policies and budgets. In a number of ways, their activities collectively determined the S&T policy of the nation, which was constrained by economic realities and competing priorities that limited the mandates of the Vision. When President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took the reins, for example, he was to chair a national council that would address the most important S&T issues facing the country. After several meetings—directed in large measure

___________________

5 Reza Mansouri, former Deputy Minister of Science, Research, and Technology, “Presentation,” Washington, D.C., September 13, 2006.

to the responsibilities of universities, which were soon to be guided by newly appointed rectors—he focused on economic and other issues; and the council played a largely passive role in promoting development and implementation of a rational S&T policy for the nation. The ministries continued to establish their own policies—at times in consultation with many stakeholders at the highest level of government and at other times largely on their own.6

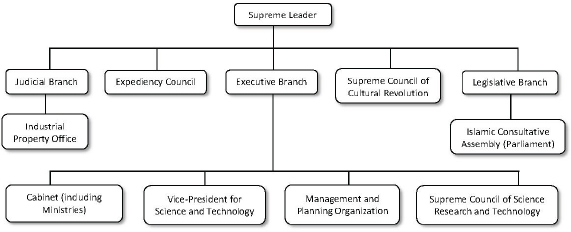

As of 2016, the formal organizational structure for formulating science and technology policy within Iran is set forth in Figure 2-1. However, as discussed below, this structure does not adequately reflect the importance of the ministries and companies in influencing policy and in determining both the courses of development and the implementation of activities that are within their purview.

In many respects, the importance of the ministries in determining the policies of the country have long been linked to their access to funds for supporting their special interests. At the top of the list of the best-endowed organizations that support research have traditionally been the Ministry of

___________________

6 Information provided by group of policy-oriented Iranian scientists during a National Academies planning visit to Iran, Tehran, January 2007.

Defense, Ministry of Oil, and Ministry of Energy. Of course, the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology (Ministry of Science) and the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (Ministry of Health) have long played key roles in guiding the universities, but their funds available to the universities have been limited. These two ministries and other government bodies also allocate limited funds to their research centers that should provide leadership for the country in selected areas.

By 2007, the Iranian government had appointed a Vice President for Science and Technology. That official’s influence was to be wielded primarily through a relatively small research fund that the Vice President’s office controlled. However, the fund did not grow to reach its financial goals; and much of the limited funding was allocated for short-term projects of immediate interest to the country’s political leadership.

Shortly thereafter, a reorganization placed 15 offices, institutes, and agencies interested in technological advancement within the framework of the Office of the Vice President. By 2014, this cluster of organizations had significantly expanded the reach and influence of the Vice President. An estimate of the annual budget resources of this office at that time was $500 million available to support research.7

In 2012, the Office of the Vice President published a list of seven priority areas for technological development, which is set forth below. These priorities have been refined on an annual basis. Meanwhile, individual ministries and other governmental bodies have supported their own priorities, which often overlapped with the national priorities financed by the Office of the Vice President.

- Biotechnology: Pharmaceuticals: interferon, growth hormones, and recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Biomedicine: medical genetics for early detection, Schwann cell therapy, and bone marrow transplants. Bio-agriculture: foot and mouth vaccines, bio-fertilizers, bio-pesticides and bio-herbicides. Bioengineering: desludging of crude oil, control of corrosion, and media cell cultures.

- Nanotechnology: Use of scanning tunnel microscope and deep reactive ion-etching. Industrial electrolysis. Ion mobility spectroscopy. Chemical vapor deposition.

___________________

7 Comments by Vice President for Science and Technology of Iran, during his visit to the United Nations in New York, September 25, 2014.

- Advanced materials and composites technology: Resins. Glass fibers. Fajr-3 full composite aircraft. Composite folded structures. Reinforcement of gas and oil tanks and pipelines

- Information and communication technology: E-government. Analog TV transmitters and FM transmitters. Combiners and filters. Satellite translators and antennas. Persian voice dictation. Searching large-scale biometric databases.

- Energy: Captanization of petroleum fractions; Hydro-conversion. Light naphtha isomerization. Renewable energy including hydro, wind, solar, geothermal, and biogas; Hydrogen fuel cells.

- Aerospace. Omid satellite for research data processing. Rasad 1 satellite for environmental monitoring. Data collection in thin atmospheres.

- Marine: Shipbuilding. Fisheries. Offshore seabed exploration. Offshore rig repair services.8

Examples of new technological interests that were subsequently adopted by the office are (a) water and waste water treatment with an emphasis on desalination, disinfection and purification, emergency water treatment, and expanded use of ground penetrating radar in the assessment of underground aquifers; and (b) high performance concrete and thermal insulation of composite systems to support urban development.9

Turning to the role of technology-oriented companies, until 2010 their potential contributions had not received much attention by the government, which focused on strengthening the scientific capabilities of government universities and research institutes as the primary route to a knowledge-based economy. When funds from exports of oil and raw materials were plentiful, necessary technologies were readily imported; and limited attention was given to developing the advanced engineering potential of even state-controlled enterprises. But as import opportunities declined due to sanctions and the increasing economic crisis, the government significantly increased its efforts to strengthen the technological contributions of knowledge-based companies—both in the public and private sector.

___________________

8 Center for Innovation and Technology Cooperation, A Summary of Selected Technological Achievements in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Tehran, 2012.

9 Technologies Studies Institute, A Brief Representation of Technological Achievements in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Tehran, August 2014.

By the end of 2015, more than 1,800 companies had been certified as knowledge-based enterprises, reflecting the expanded government support of such companies. Many of these companies did not achieve their lofty goals, despite financial incentives. These incentives included tax and tariff breaks for 15 years, long-term and short-term loans at low interest rates, priorities in techno-parks and special economic zones, and financed guaranties on quality products from production through distribution and use. While the survival and success of many of the firms have yet to be determined, the focus on private companies—including both partially owned government enterprises and completely private firms—has certainly captured the attention of high-tech aspirants throughout the country.10

Representatives of these companies began playing increasingly active roles in science-engagement activities with western counterparts, particularly in exchanges supported by European organizations. In an unusual instance, one of the National Academies’ key partners in Iran proposed sending representatives of 15 small companies who were interested in the topic of entrepreneurship to the United States on a visit to be programed by the National Academies. In consultation with the department, the National Academies considered this proposal to be a good step forward in encouraging development of newly organized private firms, which were seeking greater independence from the government. However, when the entrepreneurs applied for visas, other U.S. government agencies objected due to concerns over access to U.S. technologies even though the program was to focus on management, financing, and marketing and not on specific technological developments. On several other occasions, a few aspiring entrepreneurs were included in the National Academies’ other engagement activities that were limited to environmental, solar energy, and other “non-sensitive” issues.

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY GOALS

Given the foregoing developments, the key targets as of 2013 for growing the importance of S&T in Iran were the following:

- Raise investments in research and development (R&D) to 4 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2025.

- Raise investments by companies in R&D to 50 percent of national investments by 2025.

___________________

- Raise the share of researchers employed in the business sector to 40 percent of the country’s researchers by 2025.

- Increase the number of full-time university professors per million of the population to 2,000 by 2025.

- Privatize 80 percent of state-owned firms by 2014.

- Raise foreign direct investment to 3 percent of GDP by 2015.

- Increase by four times the publication of scientific articles in international journals by 2025.11

These goals were clearly aspirational goals, and it soon seemed clear that few if any of the goals would be met. Nevertheless, they indicated the ambitions of important components of the government in moving toward a knowledge-based economy. These and other goals, along with implementation and financial details, are set forth in Appendix C. Appendix D highlights relevant policies and plans of the government.

GOVERNMENT RESEARCH CENTERS

In the early 2000s, the Ministry of Science reported the number of government research centers, with many affiliated with state universities, as follows: Research Centers of Ministry of Science (29); Research Centers of Ministry of Health (99); and Research Centers of other Ministries (69).12

In recent years the number of research centers increased dramatically. Then some centers became of reduced importance as the economy tumbled from 2010 to 2015, despite the commitment of the government to press hard in developing a knowledge-based economy as discussed above. Plans on paper were a long distance from activities in the research laboratories. A few centers are stand-alone centers, while others are subordinate to universities or other parent institutions. Twelve of the centers have long been considered by the Iranian government as “major” centers and have with some difficulty withstood the economic slump of recent years. They are set forth in Box 2-2. All of these centers have international connections, and they presumably are well aware of many relevant research efforts in the United States.

Early in the 2000s, the government selected nanotechnology as an emerging technology that deserved strong government research support—focused particularly on the biotechnology sector—which in the near term

___________________

11 Kioomars Ashtarian, “Iran,” UNESCO Science Report 2015, Paris, 2015, p. 389.

12 “Report,” Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology, Tehran, June 2009.

could lead to economic payoff. Research increased, with the Center of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, the Razi Institute, and the Pasteur Institute playing leading roles. By 2014, more than 140 companies of various sizes and capabilities were engaged in research and in attempting to take biotech achievements into the market place. Spurred by these and other developments, Iranian researchers claimed seventh place in the number of international publications on nanotechnology among the countries engaged in relevant research. However, concerns mounted in Tehran that quantity and not quality had become the primary metric of success.13

While government and university centers dominate the research scene, several quasi-independent institutions are also important. For example, the Royan Research Center for Reproductive Medicine, Cell Biology, and Technology has a strong reputation in stem cell research. It works collaboratively on developing leading edge approaches with several other Iranian centers

___________________

13 Ashtarian, op. cit., p. 401.

such as the Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics and the Bone Marrow Transplantation Center.

THE ACADEMIES

Iran has four academies: Academy of Sciences (reactivated in 1988), Academy of Persian Language and Literature (1990), Academy of Medical Sciences (1991), and Academy of the Arts (1998). A single Board of Trustees under the Office of the President of Iran, with the First Deputy of the President presiding, oversees the activities of the four academies. The President of Iran appoints the presidents of the academies after he receives recommendations developed during electoral processes within the academies.

The Academy of Sciences and Academy of Medical Sciences have been significant participants in international science-engagement activities during the past 15 years. Each academy elects its members, many of whom have been active internationally. Neither has research facilities. The two academies have various scientific sections, and they can mobilize scientists from a variety of institutions to assist in facilitating international contacts.14

While both academies seem far from the mainstream of national policy formulation, many of their members hold important positions in universities and other institutions. At times, their memberships in the academies add weight to the significance of activities that they undertake in their full-time positions.

Academy of Sciences

As of 2014, the Iran Academy of Sciences had 50 Fellows, 100 Associates, and five honorary members selected by the incumbent Fellows at General Assemblies of the entire membership.

Significant responsibilities of the Academy set forth in 2008 include:

- Analyses of the status of science, technology, education, and research within Iran and provision of suggestions to the government to improve conditions.

- Scientific assessments requested by the government and academic centers.

___________________

14 See ias.ac.ir, accessed February 15, 2010. Also, Academy of Medical Science of Islamic Republic of Iran, Tehran, 2010.

- Studies of experiences of other countries on development of science and technology and their applications.

- Awarding of leave and scholarships for international contacts.

- Organization of seminars and conferences.

- Publication of journals, with the best developed journal being devoted to engineering education.

- Representation of Iran in international organizations and societies with comparable aims and responsibilities.15

The departments of the Academy are as follows: Agricultural Sciences, Basic Sciences, Engineering Sciences, Human Sciences, Islamic Sciences, and Veterinary Sciences, Also, there is an Office for Foresight Studies.

In recent years, the Academy has become more active than in earlier times in providing advice to the government on policies governing research and related activities. This development is consistent with global trends for such academies to stretch beyond traditional interests in the history of science to the applications and the policy implications of research at the national, regional, and global levels.

Of importance in establishing a policy role for the Academy of Sciences was a message from the Academy to the newly elected President of Iran in 2013 that covered the following topics:

- Authority of the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology.

- Recognition of the independence of universities.

- Role of professors in selection of executives of universities.

- Improving relations between universities and society.

- Rethinking university regulations and codes.

- Decentralizing admission of Ph.D. students.

- International cooperation with prestigious universities and institutions.16

The Iran Academy of Sciences has been an important partner of the National Academies in organizing bilateral workshops, meetings, and other cooperative activities. The National Academies has agreements for cooperation with many foreign academies. However, according to its staff, during the

___________________

15The Academy of Science, Islamic Republic of Iran, Tehran, 2007-2008.

16 “A Message to the New President of Iran,” Academy of Sciences of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2013.

early 2000s the Iranian Academy of Sciences’ cooperative activities with the National Academies were by far its most active bilateral engagement efforts.

Of particular interest in considering science-engagement has been the capability of the Iranian Academy of Sciences to attract leading scientists from many institutions to participate in bilateral events. Typically, 5 to 10 Iranian universities, government agencies, and other organizations have been represented in scientific workshops in the United States jointly organized by the academies of the two countries. For events in Iran or other countries, the Iranian Academy has reached well beyond the best-known institutions in Tehran, Shiraz, and Esfahan.

At the same time, the Academy is careful to ensure that the activities it sponsors, and particularly international activities, are appropriately coordinated throughout the Iranian government. Such coordination for a single international workshop may require up to six months. Indeed, government agencies in Tehran have not always given the green light for proposed international workshops; but the Academy has been helpful in reshaping approaches to ensure that the proposals are politically acceptable.

The projects of the Academy are limited in number and scope. However, the importance of the Academy cannot be measured simply by examining the limited impacts of its own projects. The membership of the Academy includes leaders of science from many institutions; and at times they collectively try to influence the policies that constitute a portion of Iran’s national science policy. Even though most members are based at academic institutions, a number of these professors rotate in and out of government positions; and most have some type of personal linkages to national and regional political leaders. Thus, influence is reflected in informal, as well as in formal, interactions.

Academy of Medical Sciences17

The goal of the Academy of Medical Sciences is “to achieve scientific and cultural independence in the field of medical sciences and promote the art of medical research. Also, it is to support medical innovations in the country, including the support of projects involving young researchers.” In 2015, the Academy had 32 members and 30 affiliate members. It had departments for

___________________

17 Much of the information in this section is supplemented by discussions on the academy’s website. Also, members of the academy are quite outspoken concerning the responsibilities and work of the academy.

Clinical Sciences, Basic Medical Sciences, Nursing, Pharmacy, Dentistry, Public Health and Food, Traditional and Islamic Medical Sciences, and Women Specialists and Consultants.

One group of American visitors to the Academy was very impressed by the attention given to the successes of Iranian surgeons in performing transplantation of important organs. These operations have included not only routine kidney transplants but also difficult liver transplants, for example. In cooperation with the Tehran University of Medical Science and other leading research centers, the Academy carries out a program of careful tracking of both donors and recipients following operations and has accumulated extensive records that provide guidance on maintaining healthy lifestyles following such major surgeries.18

Also of importance to the Academy are its many publications in Farsi and in English that report on the achievements of the medical science community. Walking through the Academy, visitors can observe writers and editors busy at work preparing articles for publication and dissemination. It is difficult to depart from the Academy without an armful of scientific publications reflecting research-oriented activities of the members. Iranian scientific leaders claim that the country produces more than two times the number of scientific journal articles than the number produced by all Arab countries combined, and it seems that medical publications are one of the reasons for this impressive record.19

As an example of issues that have been of interest, in 2015 the Academy was actively pursuing (a) tobacco dependence and smuggling, (b) health impacts of pesticide residues in food, including leukemia, (c) air quality and clean air standards, (d) outbreak of malaria, (e) regulation of bottled water, and (f) new health-care facilities. Such interests are a welcome expansion of the traditional and important focus of the academy on publications reporting on results of medical research by individuals and by groups of laboratory investigators.

As to international interests, over the years the Academy has given importance to cooperation with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the University of Sao Paulo, the University of Michigan, and the French National Center for Scientific Research. Other universities of interest to the Academy include the University of Washington, Stanford University, University of California in Los Angeles, and University of California in San Diego.

___________________

18 Visit to Academy of Medical Science, June 27, 2007.

19 Ibid.

UNIVERSITIES AND OTHER INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION

The Iranian ministries, the Parliament, the Organization for Management and Planning, and the Supreme Council for Cultural Relations play important roles in influencing the policies and planning activities that shape the higher education system of the country. The executive power of the government for overseeing the universities is vested primarily within the Ministry of Science and the Ministry of Health. As previously noted, other ministries—such as the Ministry of Oil, the Ministry of Energy, and the Ministry of Defense—also have significant roles in determining the course of research and higher education.

According to Iranian colleagues, the research funds available from the Ministries of Oil, Energy, and Defense dwarf the research funds available from the ministries that are directly responsible for science and for health. For example, the Iranian press reported in 2007 that one important university had 150 contracts with the Ministry of Defense. This approach seems to parallel the approach of the defense agencies in the United States and other western countries in tapping the broad academic community for ideas and technologies that are relevant to national security interests.20

At the university level, policy-making and planning are responsibilities of the university leaderships. The government universities operate under the direction of rectors, who are appointed by the ministries, or by boards of trustees, university councils, and departmental councils. The private universities have their own approaches to governance.

As of 2016, according to available information, 220 government universities were active, with 154 operating under the auspices of the Ministry of Science, 58 operating under the auspices of the Ministry of Health, and a few others reporting to other ministries.

Relevant statistics concerning the universities as of 2015 are set forth in Box 2-3.

A particularly important responsibility of the medical universities is their management of a significant portion of the country’s public health system. Most medical universities have responsibility for providing primary care health services for designated geographic areas that blanket the country, in addition to their educational and research responsibilities. The National

___________________

20Tehran Times, “Headlines,” March 15, 2007, stating that 450 Iranian universities have defense contracts. Also, “University Handling 150 Defense Projects,” Iran Daily, October 11, 2003, p. 1.

Academies’ most ambitious joint project focused on improving services in addressing food-borne diseases, and the collaborators in this project were the Oregon State Health Department and Shaheeb Beheshti Medical University. The support of the Iranian government for the university’s outreach activities, which involved hundreds of volunteer health workers in rural areas who were trained by the university, was very impressive.

Techno-parks and business incubators have significantly expanded, both in number and activities, during the past decade, with many located at or near universities. According to the Ministry of Science, in 2015 there were 36 techno-parks (including 160 business incubators) that were hosting 3,400 companies, and employing 22,000 scientists. Several hundred patents had been awarded to residents of techno-parks. Accelerator organizations were also established to provide funding for start-up companies in exchange for equity in the companies.21

In May 2014, the Minister of Labor and Social Security reported that about 4.5 million university graduates would enter the labor market in the next few years. Meanwhile, 2.5-3.0 million working-age adult Iranians were already unemployed and looking for work. The unemployment rate among university graduates was 20 percent with a large number of holders of master’s and PhD degrees seeking employment. When university graduates with bachelor’s degrees cannot find suitable jobs that match their skills, they have several options including acceptance of a low-skill job, waiting until a suitable job is found, or going back to the university to obtain a graduate degree. For male students, the decision is sometimes inter-woven with compulsory military service.22

In short, many Iranians are highly focused on university education; and families go to great lengths to send their children to a university. They view a university degree as both a ticket to economic success and a source of social status. Their pre-occupation with a university degree has been reinforced by policies of the government that require a degree for employment in most public sector jobs. Also candidates for many elected positions, such as members of city councils, must hold university degrees.23

Can expanded cooperation with U.S. universities help resolve the employment crisis? Certainly not in the near-term. But perhaps in the long-term, exposure of Iranian educators to approaches in the United States, and probably more important in economically progressive middle-income countries such as South Korea (a model country often cited by Iranian economists), could encourage new innovative efforts, which generate income.

___________________

21 Ashtarian, op. cit., p. 403.

22 Haribi, op. cit., supplemented with observations of the author.

23 Ibid.

JOINT PUBLICATIONS24

An increasing number of Iranian scientists, including a large number who have occupied important government positions, have long been aware of the importance of internationally accepted scientific publications. They know the requirements for publishing in journals that are covered in the Web of Science Citation Index, which is maintained by the International Science Information (ISI) organization. At the same time they seek the prestige and the development of new international contacts associated with publication in international journals. However, many Iranian scientists have not yet ventured into this unfamiliar area, confining their publications to Iranian journals, and particularly Farsi-language journals, which may not meet international standards.

During the late 1990s, a dramatic upsurge in the number of papers being published by Iranian scientists in international English-language journals began. Starting near the bottom of the list of middle-income countries ranked according to their scientific publications, Iran rapidly climbed to a leadership position in the Middle East. Within a decade the country ranked side-by-side with Turkey and Egypt as the scientific achievers of the region. There were several reasons for this sharp upward trend.

- The Iran-Iraq war had come to an end, and university students developed new interests in becoming members of the global scientific community.

- A number of Iranian universities established Ph.D. programs that led to increased faculty and student interest in addressing scientific problems that they were studying in depth.

- A new era of international scientific collaboration began as many scientists leaving the country stayed in contact with their mentors, colleagues, and students still in Iran. Jointly authored publications provided convenient avenues for staying in touch.

- The Iranian government, individual Iranian organizations, and even international organizations financed sabbatical leaves abroad for Iranian university professors who then had new opportunities to address developments on the cutting edge of their fields of interest.

___________________

24 See Malise Nikzad, “Foreigners’ Point of View toward Collaboration with Iranian Authors,” Webology, Volume 9, No. 2, Dec. 2012. He surveyed 320 Iranian authors with 55 percent response. Major findings were (a) main reason for cooperation is new knowledge, and (b) major factor in stimulating cooperation is previous study abroad.

- Soon, Iranian scientists began to have more confidence in the integrity of their own research; and they became less hesitant in trying to have their works accepted by international journals.

- Finally, international data bases were coming on line; and Iranian researchers could obtain copies of publications of others as they weighed the opportunities for publishing the results of their investigations.25

Against this background, within the 10-year period of 1995-2005, the number of Iranian-authored papers in the natural sciences and engineering published in ISI journals went from 1,500 to 5,500. By 2013, the number had reached 24,000.26 In the field of medical research, citations of articles published by Iranian scientists has been particularly impressive. Beginning at nearly zero in 1986, by 2006 the number had risen to 8,000, surpassing citations of articles prepared at Turkish institutions, for example.27Appendix E sets forth the results of a search by the National Academies of Iranian scientific publications.

Turning to co-authorship of scientific papers in ISI journals, more than 22 percent of Iranian publications had co-authorship during the period 2008-2014. American collaborators were the most prevalent, followed by co-authors from Canada, the United Kingdom, and Germany.28

THE OVERHANG OF SANCTIONS

This chapter concludes with optimistic pronouncements from two of Iran’s experts on science, technology, and innovation policies of the country. One contends that sanctions have forced Iran to strengthen its internal scientific capabilities rather than to look abroad for scientific achievements that lead to economic success. The sanctions of concern were as follows: during the hostage crisis (1979-1981), during the Iran-Iraq war (1981-1988), during post-war reconstruction (1989-92), during the Clinton administration (1993-2001), after the 9/11 attacks (2001-2006), and during the Ahmadinejad administration (2004-2012).29 According to the other expert,

___________________

25 Ashtarian, op. cit., supplemented by Soofi, 2017, Chapter 5.

26National Report on Higher Education, Iran (2011-2012), Institute of Planning in Higher Education, Tehran, 2013, p. 2.

27 Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology, January 2013.

28 Ashtarian, op. cit., p. 390.

29 Soofi, 2017, p. 251.

“More than any other factor, the growing importance of science, technology, and innovation policy in Iran is a consequence of the tougher international sanctions. Science can grow under an embargo. This realization offers a hope for a brighter future in Iran.”30 Others argue that there may well be short-term benefits from sanctions; but the long-term negative impacts of sanctions that reduce available funds for supporting education and research limit access to international technologies and inhibit international scientific cooperation.

That said, long-term sanctions will probably have a corrosive effect on efforts of Iran to develop a stable and modern infrastructure for supporting a knowledge-based economy. Of particular relevance for this report, the overhang of sanctions will continue to complicate effective U.S.-Iran science-engagement as discussed in Chapter 4.

__________________

30 Ashtarian, op. cit., p. 403.

This page intentionally left blank.