Appendix B

Risk and Risk Management

In this report the committee has adopted the conceptual foundation and nomenclature of the national-security community and defined risk in terms of a threat or hazard, the bad consequences that can arise from that condition, and the probability and severity of those consequences. Specifically, the committee has worked with definitions from national-security doctrine that are broadly applicable with minor adaptations.32,33 These definitions include the following:

- Risk: probability and severity of loss linked to hazards.

- Hazard: a condition with the potential to cause injury, illness, or death of personnel; damage to or loss of equipment or property; or mission degradation.

- Probability: the likelihood that an event will occur in an exposure interval (time, area, etc.), ranging from frequent or inevitable to unlikely or improbable.

- Severity: the expected consequences of an event in terms of injury, property damage, or other mission-impairing factors, ranging from catastrophic to negligible.

The committee has drawn from this doctrine, but paraphrased and adapted it for the report’s purposes.

This doctrine dates back to the 1980s239 and largely parallels the guidance of other federal agencies, including those with civilian and strategic concerns, for example, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)240 and the Department of Transportation.241 DHS defines risk similarly as the “potential for an unwanted outcome resulting from an incident, event, or occurrence, as determined by its

likelihood and the associated consequences.”242 The committee chose to work with the national-security doctrine because of its maturity and utility. It pinpoints two concrete facets of risk—probability and severity—and ties them to a set of practical risk-management tools that can support qualitative analysis. Those tools are not without criticism, which the committee addresses in a later note in this appendix.243,244 For a review of the strengths and weaknesses of DHS’s approach to risk analysis, see the cited literature.245

Two aspects of the committee’s use of this vocabulary merit attention. First, whereas the national-security doctrine focuses on personnel and mission, the committee has adopted a broader lens that encompasses individuals, public and private institutions, and the environment. Second, the doctrine acknowledges the potential for losses from hazards (accidental), threats (tactical), acts of terrorism, suicide, homicide, illness, or substance abuse, but it refers to hazards holistically;32 for consistency, the committee also uses the term hazards in this appendix, but it highlights specific concerns about potential losses from acts of terrorism. In the main text of the report, the committee also refers to threats, but does so broadly, to encompass a wide range of tactical and other concerns, including those of terrorism. Whether a hazard or a threat, the condition under consideration can lead to injury, illness, death, or damage, with a particular probability and severity.

Generally speaking, a hazard can be viewed as a condition that might give rise to an event that can be more or less likely (probability) and entail more or less damage (severity). For example, a family might store an ignitable material, such as turpentine, near a gas heater in a basement. This storage arrangement poses a hazard that might lead eventually to a fire, entailing physical injury and property destruction. The odds of the fire could be high or low and the amount of damage could be marginal or catastrophic, depending on whether the basement is cluttered or family members are home. A public safety officer might be interested in helping families to reduce the probability of fire by addressing the conditions under which the fire can occur.

In this report, the committee is interested in identifying conditions under which terrorists can obtain chemicals to produce IEDs and means of reducing the odds that precursor chemicals fall into the wrong hands as fodder for a terrorist episode, which is the ultimate event of concern. To that end, one might consider whether a chemical can be or has been used in an IED and whether and how a terrorist might lay hands on it. Alternatively, the problem could be framed in terms of episode risk (RE) and precursor risk (RP). The former is a function of the probability (PE) and severity (SE) of the episode (Equation B-1), while the latter is a function of the probability of observing the use of the precursor (PP) given the episode or concern for the episode and its associated risk (Equation B-2). PP will be dependent on constituent factors, such as the ease of extracting a precursor chemical from a product or formulation and the attendant personal dangers of handling it.

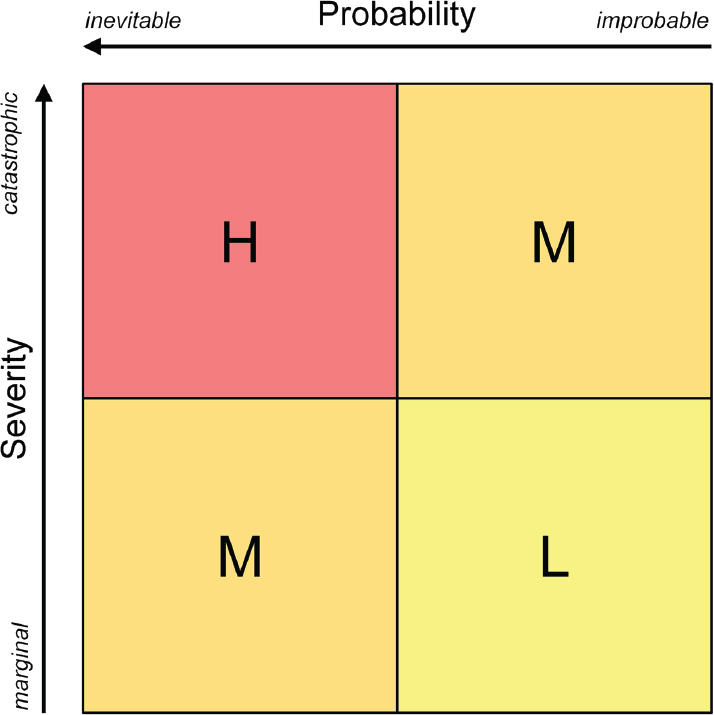

The national-security doctrine juxtaposes probability and severity in a risk matrix that can be used to evaluate the risk level of a particular hazard and inform, if not establish, mitigation priorities; the doctrine addresses both severity and probability to distinguish, for example, the hundred-year storm, the tsunami, and seasonal flooding. Therefore, the possibility of a moderately harmful but likely event might generate as much concern as the possibility of a catastrophic but unlikely event. Quantitative data, for example, rates of occurrence, illness, injury, death, or damage, should be used to support the assessment, if available, but are not absolutely necessary.

In the committee’s simplified rendering of the standard matrix (Figure B-1), risk levels reside in four quadrants, range from high (red) to low (yellow), and depend equally on probability and severity, but other more-sophisticated formulations are possible. The doctrinal version is asymmetric, provides more categories for probability and severity, and, in some instances, gives slightly more weight to severity than probability.32,33 Nonlinear permutations are also possible.237

The matrix presents an initial basis for considering, if not establishing, priorities across scenarios, chemicals, and policy responses and can be used in at least three ways. One could start a risk analysis from the end of a narrative with a set of scenarios—that is, types of terrorist episodes of particular concern because of their riskiness—and back out to a set of chemicals of interest; one could start the analysis from the beginning with a set of chemicals and track them forward to scenarios, by asking what risks each presents under what conditions, with what likelihood and severity; or one could approach the analysis from both directions and iterate toward convergence.

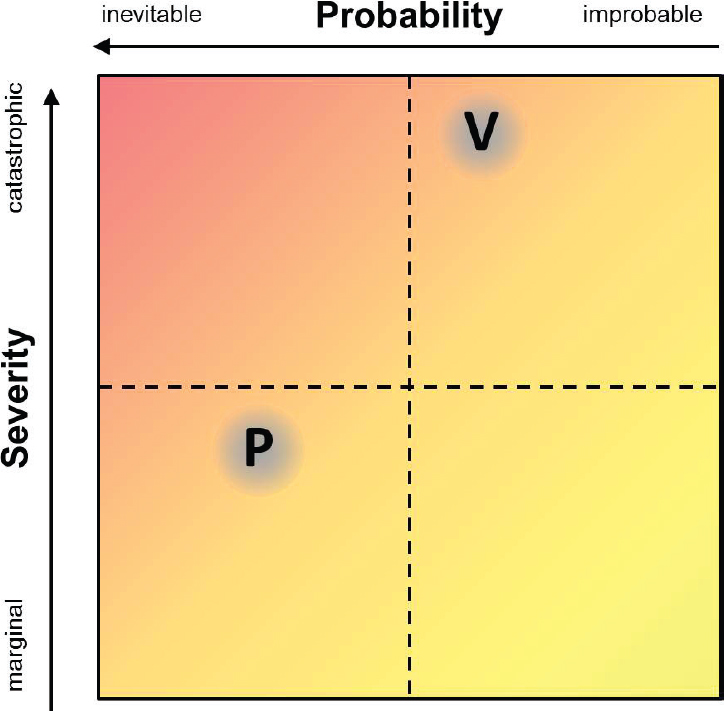

Preliminary to any such approach, the matrix can be used to establish whether an episode is of particular concern, depending on whether it is sufficiently risky. For example, a scenario involving a larger-scale explosive device, such as a truck bomb, could entail substantially more damage than a scenario involving a smaller-scale, person-borne device, such as a backpack bomb, but could be far less likely; thus, the risk of either scenario might rate concern. If taking the scenario-by-scenario approach, one could identify the chemicals that terrorists can use to produce each type of device and the conditions (e.g., relating to availability and other factors) under which they can obtain them; develop strategies to reduce the odds of terrorists getting access to the chemicals; and, ultimately, lessen the risk of either scenario. By limiting the analysis to a set of scenarios, one can focus attention on a single dimension of precursor risk, namely, the probability of observing the use of the precursor, given concern for the episode (Equation B-2). Figure B-2 redraws the matrix as a continuum without strict

rankings, in which the risks of vehicle- and person-borne episodes are at similar levels and potentially reducible.

However, the matrix, even with elaboration, cannot provide definitive guidance for establishing priorities, in part, because it is silent on the feasibility and costs of mitigation options. If relying only on the matrix, a policy maker might inadvertently ignore low-hanging fruit or suggest dedicating inordinate resources to the impossible; a low risk might have an easy and cheap fix whereas a medium risk might have no feasible or affordable remedy.

Researchers offer a number of criticisms of qualitative tools and methods of analysis, including risk matrices. While acknowledging the popularity of matrices, they warn against a lack of scientific validation and the drawbacks of using them indiscriminately.243,244 For example, correlations between severity

and probability can invert results. Lundberg and Willis offer remarks on the imperfection of various analytical options:246 “While some articles have explored the reasons to be cautious about the use of qualitative risk assessment tools there are also reasons to be cautious about the use of quantitative estimates”; the latter point is further explored elsewhere.245

The decision to start or stop mitigating risk also requires consideration of risk tolerance and the acceptability of residual risk. The former refers to the level of risk below which a hazard does not warrant any expenditure of resources on mitigation, and the latter refers to the amount of risk that remains after mitigation. If the initial level of risk is low enough to be tolerable absent any mitigation, then the residual risk would equal the initial risk. By implication, risk mitigation need not amount to risk elimination. In some instances, it might be preferable

to accept some amount of risk—initial or residual—and develop a response and recovery plan.247 Such preferences typically arise when the costs of addressing the risk outweigh the anticipated benefit.

The matrix is also silent on causality, but the cause or causes of a hazard can bear directly on policy making. Absent a thorough understanding of the underlying reasons for a hazard, a policy maker might choose a risk mitigation strategy that does not improve conditions or makes them worse.247,248 The same can be said of attempts to control risk associated with precursor chemicals.

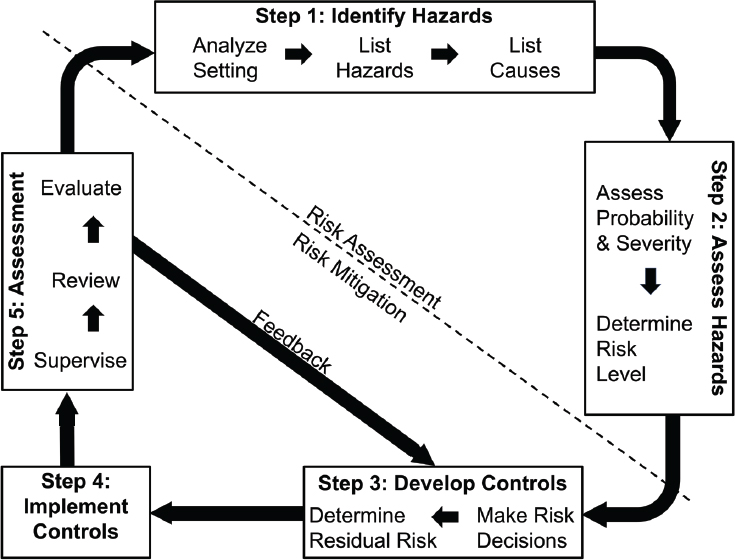

Fortunately, the risk matrix is just one tool for managing risk, and national-security doctrine nests it in a continuous five-step risk-management process (Figure B-3) that addresses these and other concerns, potentially including those pertaining to operational dynamics and behavioral adaptations. A particular hazard might present a low-level risk in one moment and a high-level risk in another and, even if policy makers have a firm grasp on causality, efforts to control risk can entail unintended consequences that give rise to new and different risks. Taking action in one arena might result in displacement and merely push the risk elsewhere. The five-step risk-management process allows—and even requires—deeper, ongoing consideration of risks, controls, and consequences and provides

explicit means to incorporate new information and address changes in circumstances. Whereas the matrix is inherently static, the five-step process, which forms an unending loop, is inherently dynamic. This meets the fourth principle of risk management, “apply risk management cyclically and continuously.”32,33

In Figure B-3, steps 1 and 2—which include hazard identification and address causality, probability, and severity—constitute risk assessment, and steps 3 through 5 constitute risk mitigation.247 From the national-security doctrine,32

Steps 3 through 5 are the essential follow-through actions to manage risk effectively. In these steps, leaders balance risk against costs and take appropriate actions to eliminate unnecessary risk and accept residual risk at the appropriate level. During execution, leaders continuously assess the risk to the overall mission and to those involved in the task. Finally, leaders and individuals evaluate the effectiveness of controls and provide lessons learned so that [they and] others may benefit from the experience.

Steps 4 and 5 generate experience and feedback, which can either validate the current approach or suggest the need for a change of course or a procedural refinement, whether applying the process in a military or civilian setting.

This page intentionally left blank.