CHAPTER 3

Institutional Setting: Developing a Common Understanding

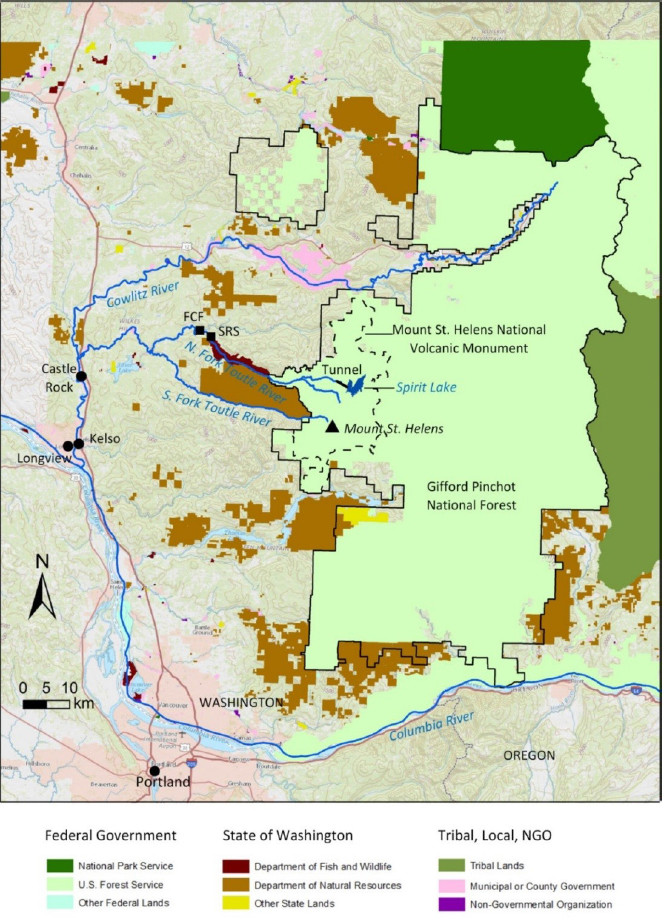

Ownership of land surrounding Mount St. Helens is both private and public, but the focus of discussion in this report (a decision framework for management of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system) is largely related to features on publicly owned land. Management of those lands and the waters and ecological features of the region is thus influenced and guided by public agencies that operate under multiple management missions and mandates. The most prominent of the federal agencies in the area are the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The Washington State Department of Natural Resources (WADNR) owns and administers large parcels of land in the region, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) manages key areas along the North Fork Toutle River. Additional areas in the region fall under tribal, county, or municipal management (see Figure 3.1). There are also a number of individuals, organizations, institutions, groups, and communities who may be directly or indirectly affected by decisions associated with Spirit Lake and the Toutle River.

Understanding the historical and contemporary management contexts (i.e., the institutional setting) of the areas affected by management actions—for example, those involving the Spirit Lake outflow and the downstream sediment retention structure (SRS) on the Toutle River—is

important in the development and implementation of a successful decision framework. The public agencies with roles and interests in the management of Spirit Lake, the existing tunnel, and the potential impacts of management or failure are thus discussed below.

PRE-ERUPTION (1980) MANAGEMENT CONTEXT: SPIRIT LAKE AND MOUNT ST. HELENS

At the time of the May 1980 eruption, Mount St. Helens and the areas immediately surrounding it were located within the boundary of Gifford Pinchot National Forest (GPNF) and managed by the USFS, which is part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (see Box 3.1). The primary goal of the USFS is to manage national forests to sustain “the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.”1 The GPNF is managed for a range of purposes, including timber, range, water, wildlife, and outdoor recreation within larger directives associated with the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 19602 and other federal legislation (GPO, 2011). Following passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act,3 several areas within the GPNF were designated as Wilderness, which placed constraints on allowable land uses and management activities. Areas within the GPNF boundary serve as the headwaters of more than a dozen significant rivers and streams, including the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers, which are the focus of this report.

Prior to the 1980 eruption, individual management plans had been established for different management units within the GPNF. Passage of the National Forest Management Act4 (NFMA) in 1976 mandated that each National Forest implement an improved process for establishing land allocations, management goals and objectives, and standards and guidelines used by land managers, other government agencies, private organizations, and individuals. Two important aspects of NFMA were that it required the

___________________

1 See http://www.fs.fed.us/about-agency.

2 See http://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/86/517.pdf.

USFS to use a systematic and interdisciplinary approach to resource management and that it provided for public involvement in preparing and revising forest plans. The GPNF published its first Land and Resource Management Plan (Forest Plan) in 1990. That Forest Plan described resource management practices, levels of resource production and management, and the availability and suitability of lands for resource management.5 Management of the GPNF has since been further circumscribed by standards and guidelines addressing major issues and management concerns at the

___________________

5 See http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5444081.pdf.

regional level (e.g., the Northwest Forest Plan).6 The USFS has also made several amendments to its original Forest Plan since 1990.

The guiding principles of land and forest management that were in place at the GPNF at the time of the 1980 eruption were defined and shaped by more than a century of evolving attitudes regarding public (and private) lands management in the United States. These attitudes, in turn, stemmed from a complex set of viewpoints and ideals concerning the values of nature and wilderness that first coalesced during the early conservation movement of the late 1800s and early 1900s, as exemplified by such figures as George Perkins Marsh, George Bird Grinnell, John Muir, and Gifford Pinchot, among many others. In particular, emerging approaches to public land management that began in the late 1800s with the creation of the first National Parks and Forests were heavily rooted in notions of land and property ownership that had distinctly European bases. These ideas became codified through a century of environmental legislation and laws concerning public lands management, which culminated in passage of several important acts in the 1960s and 1970s central to managing the GPNF, including the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the Wilderness Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).7

LAND OWNERSHIP IN THE BROADER TOUTLE RIVER VALLEY CIRCA 1980

Most land in the Toutle River valley outside the GPNF boundary was privately owned prior to 1980. Following the arrival of European trappers in the region in the early 19th century, Fort Vancouver was founded in 1825 on the north bank of the Columbia River near present-day Portland, Oregon, as the first permanent European settlement (Wilma, 2005). By the start of the 20th century, and with the establishment of the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve, miners, loggers, homesteaders, and ranchers had moved into the Toutle River valley and the area surrounding Mount St. Helens to farm in

___________________

the river valleys and raise cattle and sheep in meadows and prairies.8 Forests in the area represented some of the best timber in the nation at the time of the eruption, and logging on public and private lands supported a thriving timber industry that in 1978 contributed 44% of the total wages and salaries in Cowlitz County (USACE, 1983). The Weyerhaeuser Company owned much of the land immediately west of the GPNF at the time of the eruption.

Tourism in the valley was strong and centered on hunting (e.g., elk, deer), fishing (especially salmon and steelhead), and other outdoor activities. Spirit Lake itself was a popular tourist destination, with six camps located along its shore and a number of lodges catering to visitors. Towns downstream of the GPNF include Toutle (near the confluence of the North Fork and the South Fork Toutle Rivers); Castle Rock (on the Cowlitz River just below its confluence with the Toutle River); Lexington (on the Cowlitz River approximately 10 miles [16 km] downriver from Castle Rock); and Kelso and Longview (on the Cowlitz River just above its confluence with the Columbia River; see Figure 1.2). The Port of Longview (in operation since 1921) is located at the confluence of the Cowlitz and Columbia Rivers and has had an important role in regional economic development associated with manufacturing and international trade.

POST-EVENT MANAGEMENT RESPONSES TO THE ERUPTION (1980-1989)

The eruption of Mount St. Helens on May 18, 1980, resulted in the greatest loss of life (57 deaths) and was the most economically destructive volcanic event in U.S. history. More than 200 homes, 185 miles (300 km) of highway, 47 bridges, and 15 miles (24 km) of railways were destroyed (Tilling et al., 1990). The immediate environmental effects of the eruption on forests, fish and wildlife, and waters in the blast vicinity, which are detailed in greater depth elsewhere (e.g., Dale et al., 2005a; Major et al., 2009), were extensive. Economically, it has been estimated that the total cost of damage from the eruption amounted to nearly $1 billion in losses to

___________________

8 See http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/giffordpinchot/learning/history-culture.

forestry, agriculture, buildings, and other infrastructure.9 Long-term management of sediment and flood risk involving costly engineered structures (discussed below) has been ongoing since the eruption.

The relevant management responses with respect to Spirit Lake and the Toutle River system within the first decade following the eruption are reviewed here because they provide context for understanding the current management situation. A number of management actions were taken in the immediate aftermath of the eruption to address perceived threats to human safety and economic concerns. Actions that took place within the first 2 years following the eruption included dredging of downstream rivers, modifications of levees in downstream communities, and establishment of a pumping station to stabilize the level of Spirit Lake. These activities were (1) largely financed by emergency funding and (2) based on limited data and information, as is common in emergency response situtations. Over the rest of the decade, planning focused on solutions for mitigating or managing longer-term issues in the watershed. Most notably, this included the creation of the Spirit Lake outflow tunnel and the SRS (discussed later in the chapter).

Establishment of Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument

The 110,000-acre (172-mi2 or 445-km2) Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument (the Monument) was established in August 1982 by President Ronald Reagan from lands within and adjacent to the GPNF, including areas that had been under ownership by the Weyerhaeuser Company and Burlington Northern Incorporated.10 The authorizing legislation (P.L. 97-243) explicitly stated that the Monument would be administered as “a separate unit within the boundary of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest” and managed “to protect the geologic, ecologic, and cultural re-

___________________

9 See Washington State Department of Commerce and Economic Development Research Division, as cited by Oregon State University, “Cost of Volcanic Eruptions,” http://volcano.oregonstate.edu/cost-volcanic-eruptions (accessed December 4, 2017); see also https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub1096.pdf.

10 See https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-96/pdf/STATUTE-96-Pg301.pdf.

sources, in accordance with the provisions of this Act allowing geologic forces and ecological succession to continue substantially unimpeded.”11 Specific provisions and limitations regarding scientific study and research, recreational and interpretive facilities, timber harvesting, and hunting and fishing were defined, including several with potential relevance to the decision framework outlined in this report (see Box 3.2). Finally, the authorizing legislation stipulated that the secretary of agriculture would submit a detailed and comprehensive management plan for the Monument to the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and the U.S. House of Representatives Committees on Agriculture and on Interior and Insular Affairs. The resulting Mount St. Helens National Volcanic

___________________

11 See https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-96/pdf/STATUTE-96-Pg301.pdf.

Monument FEIS (Final Environmental Impact Statement) Comprehensive Management Plan (CMP)12 has since been incorporated as a part of the GPNF Forest Plan.13 Consistent with the CMP, the USFS restricts public access to Spirit Lake and a 30,000-acre (47-mi2 or 122-km2) area of the North Fork Toutle River drainage. Off-trail travel is by permit only14 to protect ongoing and future research opportunities in this most heavily impacted portion of the 1980 blast zone. The Monument has been a venue for research on ecological succession (e.g., papers in Dale et al., 2005a) as well as volcanic and seismic risks associated with Mount St. Helens.

___________________

12 See http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd500683.pdf.

13 See http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5444081.pdf.

14 See http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprd3800649.pdf.

Management of Spirit Lake and Its Outflow

As has been described earlier in this report, avalanche and pyroclastic flow deposits from the 1980 eruption blocked the natural pre-eruption outlet of Spirit Lake to the North Fork Toutle River valley, raising concerns about the possibility of an eventual catastrophic breach and flood caused by rising lake levels (e.g., Youd et al., 1981). A chronology of the response to these concerns can be constructed based on USACE (1982), GAO (1982), and Glicken et al. (1989):

- In the spring of 1982, the USFS organized a task force chaired by John Steward (USFS) and comprised of technical specialists from the USFS, the USACE, and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), as well as a member of the Cowlitz County Board of Commissioners. The goal of the task force, which was first convened June 22, 1982, was to evaluate the flood hazards associated with Spirit Lake.

- On July 27, 1982, the task force issued an interim report recommending that an “emergency schedule condition be declared with respect to the potential natural breaching of the Spirit Lake debris dam” (USACE, 1982: 3).

- By August 1, 1982, the lake level had risen 54 feet (16.5 m) above that recorded for May 21, 1980, and the lake volume had increased 115%.

- On August 2-3, 1982, Washington Governor John Spellman declared a state of emergency for the Mount St. Helens area and sent a letter through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to President Reagan requesting that “an emergency be declared for Washington State as a result of the flood threat” (USACE, 1982: 3) and that federal aid be provided (Glicken et al., 1989).

- In response to another recommendation of the USFS task force, Jeff Sirmon (Regional Forester, USFS Pacific Northwest Region) formally requested on August 4, 1982, that the USACE “assume

-

the lead role for work related to controlling the water release from Spirit Lake.” (USACE, 1982: Inclusion 2).

- On August 19, 1982, the president declared a federal state of emergency regarding Spirit Lake under the Disaster Relief Act of 1974, directing FEMA to coordinate the federal response to the Spirit Lake emergency and authorizing use of the President’s Disaster Relief Fund to assist efforts to lower the lake’s level and lessen the flood threat (GAO, 1982). FEMA tasked the USACE with developing both interim and longer-term solutions to stabilize lake levels and address the threat of catastrophic flooding from a breach of the Spirit Lake blockage (USACE, 1982). The emergency declaration for Spirit Lake has long since lapsed under conditions of the 1976 National Emergencies Act (NEA), which prevents open-ended emergencies by stating that actions activated by an emergency declaration expire if the president expressly terminates the emergency or does not renew the emergency annually, or if each house of Congress passes a resolution terminating the emergency. (Note that this later provision was modified in 1985.)

As an immediate response, in early November 1982, the USACE constructed an emergency pumping station that began to transfer water over the debris blockage and into the North Fork Toutle River, which allowed it to regulate the level of Spirit Lake until a permanent, stable outlet could be constructed. During the summer and fall of 1981, the USACE had also constructed outlet channels to control the levels of eruption-created impoundments in nearby Coldwater and Castle Lakes, both of which also drain into the North Fork Toutle River (USACE, 1983).

After the lake level was stabilized by pumping, the USACE assessed several alternatives for a longer-term outlet for outflow from Spirit Lake on the basis of criteria related to location within the Monument, constructability, cost, and the ability to withstand impacts from future volcanic or seismic events due to the proximity of the volcano (Britton et al., 2016a). Alternatives included a buried conduit, an open channel, a tunnel (with several possible alignments, including outlets to watersheds other than the

Toutle), and a permanent pumping facility. The USACE concluded that the preferred alternative for a permanent Spirit Lake outflow was a buried conduit (USACE, 1984a). After consultation with other agencies, however, the eventual decision was to drill a gravity-fed drainage tunnel through Harry’s Ridge and into South Coldwater Creek and thence to the North Fork Toutle River. This tunnel option was favored over the buried conduit by a number of parties, including Governor Spellman, the Cowlitz County Board of Commissioners, and the USGS, because of uncertainties at the time concerning the integrity of the Spirit Lake debris dam. It was their opinion, as expressed by Governor Spellman, that: “In view of volcanic and seismic hazards, a tunnel provides greater flexibility and safety than either a buried conduit or an open channel through the debris dam” (USACE, 1984b: 358).

Through terms laid out in a 1984 Temporary Land Use Agreement and a 1986 Interagency Agreement (USFS No. 86-06-59-01), the USFS and the USACE defined responsibilities for the operation, maintenance, and funding of the Spirit Lake tunnel and the Coldwater and Castle Lake outlets. The 1986 Interagency Agreement notes:

The Corps of Engineers and the Forest Service recognize and agree that the jurisdiction and management responsibilities for the lands and related features within the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument lie with the Forest Service. It is also recognized and agreed that the Corps of Engineers, having designed and constructed the emergency protective works at Spirit Lake, Castle Lake, and Coldwater Lake, has developed especial operational and engineering knowledge of these facilities. (2)

The tunnel connecting Spirit Lake and South Coldwater Creek was finished in May 1985. As outlined in the 1986 Interagency Agreement (USFS No. 86-06-59-01), the USACE was charged with performing operation and maintenance activities on the Spirit Lake tunnel and providing inspections and restoration of Spirit Lake project construction areas during the post-construction drawdown and monitoring period (through the end of

the 1986 fiscal year). In turn, the USFS agreed to accept responsibility for operation and maintenance of the Spirit Lake tunnel protective works upon completion of the facility and during the post-construction drawdown and monitoring period.

The longer-term management of Spirit Lake and the outflow tunnel was also addressed in the 1986 Interagancy Agreement. Beginning in fiscal year 1987, the USACE agreed to (1) perform for the USFS all operation and maintenance activities, including monitoring and inspection, on the Spirit Lake tunnel and the Castle Lake and Coldwater Lake outlet facilities, and (2) coordinate all extraordinary maintenance activities with the USFS to protect the resources and values of the Monument. In exchange, the USFS agreed to budget and allot funds in successive years to the USACE for all agreed-to services for the operation and maintenance, including monitoring and inspection, of the Spirit Lake tunnel. This arrangement delineates responsibilities, but it has complicated management of the Spirit Lake outflow because the agency with the technical expertise for maintenance and repair is not that which develops the necessary budget.

Sediment Management in the Toutle-Cowlitz River System

The 1980 eruption caused a large movement of sediment into surrounding watercourses, which affected shipping and raised concerns about the threat of flooding in downstream communities. The lahar and pyroclastic flows associated with the eruption raised the level of the Cowlitz River approximately 12 feet (4 m), and sediment filling the Columbia River prevented ships from reaching or leaving Portland for more than a week (USACE, 1983). The USACE was a key participant in emergency response efforts coordinated by FEMA (see Box 3.3) (e.g., USACE, 1981). Under the authority of P.L. 84-99, Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies (33 U.S.C. 701n), the USACE immediately responded to impacts of the eruption by dredging the clogged Cowlitz and Columbia River channels and raising and strengthening levees along the Cowlitz River (USACE, 2012). In an early effort to control sediment from the Toutle River, the USACE constructed small debris retention structures on both the North and South Forks in 1980 to

limit sediment flow into the main stem Toutle River. The structure on the North Fork Toutle River was intended to be in service through 1985, but of necessity it was breached by the USACE in March 1982 to prevent uncontrolled failure of the structure while the South Fork Toutle River structure was removed in November 1982 to facilitate fish passage (USACE, 2012). In 1983, Congress authorized additional interim protection measures (including more dredging and sediment control structures) for the USACE to maintain at least 100-year flood-risk management levels along the Cowlitz River until an overall solution could be developed and implemented. From the time of the eruption until October 1985, the USACE spent more than $375 million for emergency actions (USACE, 1985).

Recognizing the expense that protracted emergency actions would impose on the federal government, President Reagan requested that the USACE prepare and evaluate alternative management strategies for dealing with the movement of Mount St. Helens–related sediment through the Toutle-Cowlitz system in a 1982 memorandum to the secretary of defense

(USACE, 1984b). From 1983 to 1985, the USACE assessed alternatives for longer-term sediment management, including plans involving dredging, levee raises, and the construction of one or more sediment retention structures. Results of an initial analysis were presented in A Comprehensive Management Plan for Responding to the Long-term Threat Created by the Eruption of Mount St. Helens (USACE, 1983); this report was followed by the subsequent environmental impact statement, Mount St. Helens, Washington, Feasibility Report and Environmental Impact Statement, Toutle, Cowlitz and Columbia Rivers (USACE, 1984b), and the final decision document, Mount St. Helens, Washington, Decision Document, Toutle, Cowlitz and Columbia Rivers (USACE, 1985). Central to the final decision were (1) the development of a sediment budget for the Toutle River system and longer-term estimates of the sediment yields and (2) comparisons of the projected environmental effects and estimated costs of the different alternatives. Of particular importance were calculated threshold values for expected sediment yield that would favor a dredging alternative versus the construction of a single sediment retention structure. It is worth noting that even today there is a relatively high degree of uncertainty regarding future sediment yield from the debris avalanche, in terms of both total yield and variability of yield (Britton et al., 2016b).

Long-term sediment control facilities were authorized under the Supplemental Appropriations Act of August 15, 1985 (P.L. 99-88). A major component of the USACE’s long-term plan was the construction of a single SRS upstream of the confluence of the Toutle and Green Rivers to reduce downstream sediment transport and deposition (see Figure 1.2 for location). The lands necessary for the SRS and its sediment retention area were condemned through actions of the Washington Department of Transportation, and the SRS was constructed from 1987 to 1989 on the North Fork Toutle River (USACE, 2012). The USACE retains ownership of the SRS structure itself, but most of the sediment plain behind the dam is under ownership by the State of Washington. Construction of the SRS was just one component of several strategies implemented by the USACE to mitigate the flood risk to downstream communities, as identified in the

1985 Mount St. Helens, Washington, Decision Document, Toutle, Cowlitz and Columbia Rivers (USACE, 1985).

Several final points are worth noting regarding USACE involvement in management of the Toutle-Cowlitz system, all of which are discussed in USACE (2012: 1-3). First, continued work on the Mount St. Helens project is accomplished under the existing open construction project that was originally authorized in August 1985 with a 50-year project life. Second, Congress directed the USACE to maintain authorized flood damage reduction benefits for the Longview, Kelso, Lexington, and Castle Rock levees along the Cowlitz River (see also USACE, 1985). Subsequent language in Section 339 of the Water Resources Development Act of 2000 authorized the USACE to maintain these flood damage reduction benefits through the end of the Mount St. Helens project planning period (2035). Finally, the State of Washington is the nonfederal sponsor of the project with cost-sharing requirements that were outlined in a 1986 Local Cooperation Agreement between the Department of the Army and the State of Washington and Cowlitz County diking districts.

ONGOING MANAGEMENT SETTING (1990-PRESENT)

The Toutle River valley has relatively few residents living in the unincorporated communities of Kid Valley, Riverdale, Toutle, and Silver Lake. Downstream of the confluence of the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers, the population rises to about 50,000 in the communities of Castle Rock, Kelso, and Longview. Efforts taken in the decade following the 1980 eruption to control the level of Spirit Lake and to minimize the downstream impacts of sediment and chronic and catastrophic flood risk have continued through maintenance, minor modifications, and repairs to the same structures over the last 25-30 years. These are documented in the sections below.

Longer-Term Management of Spirit Lake and the Spirit Lake Outflow

Current management responsibilites for the Spirit Lake outflow tunnel remain divided between the USFS and the USACE and largely reflect

decisions and agreements made more than 30 years ago. As per terms of the 1986 Interagency Agreement between the USFS and the USACE (USFS No. 86-06-59-01), the USACE was responsible for tunnel operation and maintenance while the USFS was responsible for budgeting and allotting funds for routine operation and maintenance of the tunnel as well as emergency repairs. In 2013, representatives of the USFS and the USACE signed Interagency Agreement 13-IA-11060300-004, which reaffirmed that

The Corps will perform operation and maintenance activities, including monitoring and inspection, on the Spirit Lake protective works . . . and coordinate all extraordinary maintenance activities with the Forest Service in order to protect the resources and values of the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. . . . The Corps will provide the Forest Service with recommendations on operation and maintenance needs and perform operation and maintenance work that is funded by the Forest Service. If the need arises, the Corps and Forest Service will meet annually or when required to define the operation and maintenance work to be performed by the Corps on the Spirit Lake Tunnel and lake blockages. . . . The USACE is the parent agency having designed, constructed, and maintained the tunnel since its creation. Their continuing involvement is an expedient way for the Forest Service to maintain on-the-ground knowledge for this structure.

There have been two recurring problems associated with operation of the Spirit Lake outflow tunnel, the first of which has involved the need for tunnel repairs, particularly in the area where the tunnel cuts across what is known as the Julie and Kathy L. shear zone. The USACE has conducted routine annual inspections since the Spirit Lake tunnel was completed in 1985. As described in Chapter 2, these inspections have resulted in several localized repairs to the tunnel (Britton et al., 2016a), but more problems were encountered in 1992 and 2014-2015 (with associated repairs being completed in 1996 and 2016, respectively). Funding for such repairs must be secured by the USFS, while the necessary work must be coordinated with the USACE. Repairs since the tunnel’s construction have imposed

cumulative costs of roughly $7 million, including roughly $3 million (Britton et al., 2016a) for the most recent 2015-2016 repairs.

The second recurring issue with the Spirit Lake outflow tunnel involves operations and maintenance of the tunnel intake. Spirit Lake contains a significant amount of floating, semi-submerged, and sunken wood debris as a result of the 1980 eruption. High winds can push a raft of floating wood debris such that it collects at the tunnel intake and restricts the only outlet for the lake. If such a blockage were to cause lake levels to rise to an unsafe level, the lake could breach the blockage, resulting in catastrophic flooding downstream. The USACE assessed options for managing wood blockages in the lake, with alternatives being compared on the basis of environmental constraints, material logistics, equipment concerns, long-term maintenance, constructability, aesthetics, risk, and costs (USACE, 2009). The recommended method to manage the debris was to monitor the degree of blockage and periodically remove the debris from the intake channel when data indicate there is a blockage problem.

These two issues (conducting tunnel repairs and maintaining the tunnel inflow) raise an additional concern that is relevant in the decision-making process. Access to the tunnel intake for management activities (including opening and closing the gates as well as conducting wood removal) can be dangerous, particularly during bad weather and the winter months, a concern that was voiced by USFS personnel during the committee’s open session meetings held for this project. The resulting operational risk to personnel (or decisions that reduce that risk) needs to be considered as part of the final decision-making framework.

The Toutle River System and Sediment Retention Structure

In 1985, the USACE developed a 50-year plan to manage sediment associated with the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens and to maintain authorized flood risk levels along the Cowlitz River (Britton et al., 2016b). The main feature of this plan was the SRS on the North Fork Toutle River (USACE, 1985). When the SRS was completed, flow was initially constrained through an outlet works structure within the SRS; as

sediment accumulated behind the SRS, rows of increasingly higher outlet works pipes were buried and closed (USACE, 2012; see Figure 3.2). The outlet works pipes were completely blocked by sediment by 1998 at which point all flow began passing over the spillway. The result was that a significantly larger amount of sediment began passing the structure, the coarser sandy fraction of which was deposited downstream in the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers where it had the potential to increase flood risk and affect shipping. In response to bathymetric survey data indicating that accumulated sediment had begun to impact the authorized levels of protection for Longview, the USACE dredged the lowest 5.7 miles (9.2 km) of the Cowlitz River from 2007 to 2008 (USACE, 2014). Higher-than-projected sediment accumulation resulted in the SRS beginning to fill by 2012 (USACE, 2012).

Confronted by increased sediment delivery through the SRS, yet authorized to maintain levels of flood protection identified in 1985 for Castle Rock, Lexington, Longview, and Kelso on the Cowlitz River through the year 2035 by the Water Resources Development Act of 2000 (section

339),15 the USACE began to evaluate corrective measures for managing sediment. In 2004, the USACE, the USGS, the USFS, and the WDFW began meeting to discuss options for additional sediment control (Dale et al., 2005b). Three alternatives were deemed capable of maintaining the authorized flood risk levels along the Cowlitz River: (1) a single large raising of the SRS, (2) a dredging program in the Cowlitz River, and (3) a phased approach involving three incremental SRS spillway raises coupled with the construction of grade building structures in the sediment plain above the SRS and with dredging on an as-needed basis (USACE, 2011; Britton et al., 2016b). The phased approach was selected as the least costly and most adaptable alternative, and the USACE constructed a 7-foot-high (2.1-m) concrete sill to raise the elevation of the SRS spillway in 2012 (USACE, 2012). The USACE sediment management alternatives would “address the changes to the affected environment that have occurred since the original EIS was written and evaluate the potential environmental impacts of each of the proposed long-term sediment management alternatives” (USACE, 2012: ES-7). An initial Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (DSEIS) was released for public review and comment on August 22, 2014 (USACE, 2014). Consultation between the USACE and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) delayed finalizing the SEIS. Finally, in August 2017, the NMFS provided a biological opinion in which it concluded that the USACE needed to improve fish passage at the SRS. The USACE prepared a revised DSEIS to evaluate alternatives for managing sediment as well as improving fish passage; it was released on September 15, 2017, and open for public comment until November 6, 2017 (USACE, 2017) (see also Box 3.4).

The WDFW Fish Collection Facility and Mount St. Helens Wildlife Area

Rivers near Mount St. Helens have been managed by the WDFW and its predecessor agencies for decades, with emphasis on (1) the management of salmon, steelhead, and trout species for sport harvest and (2) assuring

___________________

15 See https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-106publ541/content-detail.html.

adequate reproduction of wild fish stocks, some of which were harvested at sea or in the Columbia River (Bisson et al., 2005) (see Box 3.5). Fish species listed on the ESA are of primary management importance, including threatened and endangered salmon and steelhead species (winter steelhead [Oncorhynchus mykiss] and coho salmon [Oncorhynchus kisutch]; spring and fall Chinook salmon [Oncorhynchus tshawytscha]; and chum salmon [Oncorhynchus keta]) (USACE, 2007), as well as eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus), which was listed as threatened for the Southern Distinct Population Segment in 2010.16 The greatest production of eulachon within the conterminous United States originates in the Columbia River basin, and the major and most consistent spawning runs return to the main stem

___________________

16 See https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-04-13/pdf/2011-8822.pdf.

Columbia River and the Cowlitz River.17 Management of these species by the WDFW in the Toutle River watershed with respect to the effects of the 1980 eruption has focused heavily on two related issues: (1) the alteration of aquatic habitat by the eruption and (2) the ecological consequences of sediment management, especially construction of the SRS on fish passage.

As described in Chapter 2, environmental changes caused by the 1980 eruption devastated fish populations in the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers. Small numbers of adult salmon and steelhead managed to navigate and return in 1980 and 1981, but recreational fisheries for salmon and wild steelhead were closed immediately after the eruption and not reopened until 1987 (Bisson et al., 2005). Juvenile salmonids were found in tribu-

___________________

17 See http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/protected_species/eulachon/pacific_eulachon.html.

taries throughout the South Fork Toutle River watershed and tributaries of the North Fork Toutle River except those draining the landslide debris flow areas within 5 years of the eruption. Anadromous salmon populations below the SRS have grown due to returns of ocean-rearing individuals that were not affected by the eruption, straying from nearby populations, and reintroduction efforts by the WDFW (Liedtke et al., 2013). Hatcheries have had an important role in maintaining a number of fish populations in the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers for decades, and salmon and steelhead production in the lower Columbia River subbasin is currently dominated by fish produced in more than 20 salmon and steelhead hatcheries in the region. These fish are produced for sport and commercial harvest, to supplement natural production, and as a conservation bank for severely depleted populations. Current North Toutle Hatchery release goals are 2.5 million

sub-yearling fall Chinook salmon, 800,000 early-stock coho salmon smolts, and (from the Skamania Hatchery) 50,000 summer steelhead smolts (USACE, 2017). As habitat and fish populations have recovered, however, debates have arisen over the practice of stocking hatchery-raised fish in the North Fork Toutle–Green River system.18 Additional information on hatchery-related issues is summarized in Box 3.6 and discussed in greater detail in the Washington Lower Columbia Salmon Recovery and Fish and Wildlife Subbasin Plan (LCFRB, 2010).

The second fish species management issue involves methods used to manage eruption-related sediment. The design of the SRS is too high to include a fish ladder, and the SRS is a barrier to upstream volitional fish passage, preventing migration of species back into the North Fork Toutle River and its tributaries. As defined by the USFWS,19 volitional means that fish are able to migrate around a dam or structure through an upstream fish ladder or downstream bypass system as opposed to being trapped and hauled around the structure or attempting to move through hydropower turbines where many would be killed. Volitional fishways allow anadromous fish to migrate when they are physiologically ready and to imprint on the streams and river during their migration downriver. Species that have been particularly impacted by the SRS in the Toutle River system include Chinook and coho salmon, steelhead, sea-run cutthroat trout, and nongame species such as minnow and suckers (Bisson et al., 2005).

To mitigate impacts to fish passage from the original construction of the SRS, in the late 1980s the USACE funded habitat enhancements that included construction of a trap-and-haul Fish Collection Facility (FCF) on the North Fork Toutle River 1.3 miles (2 km) downstream from the SRS (see Figure 3.1 for location); the development of off-channel rearing areas for Cowlitz River coho salmon; and hatchery supplementation at the North Toutle Hatchery on the Green River to raise coho salmon and both spring and fall Chinook salmon (USACE, 2007). Adult steelhead and coho salmon are collected by diverting a portion of the river below the FCF

___________________

18 See http://tdn.com/news/local/anglers-protest-state-plan-to-remove-hatchery-fish-fromgreen/article_7a76805e-7a62-11e3-8ac3-0019bb2963f4.html.

into a fish ladder whence they move up into a collection pond. Fish are then moved into tanks on trucks and taken to upstream release locations. The FCF was subsequently turned over to the State of Washington and is operated and maintained by the WDFW.

Although the trap-and-haul program associated with the FCF has allowed wild coho salmon and steelhead populations to persist in the North Fork Toutle River basin, it has had limited effectiveness for roughly a decade because many of the original fish-handling features became inoperable through time due to the high sediment load of the Toutle River and because of limited staffing (Liedtke et al., 2013). The trap-and-haul program has become a labor-intensive operation for the WDFW, and in recent years, WDFW biologists, Cowlitz evaluation program staff, the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, and dedicated local volunteers have operated the facility (AMEC, 2010). A study conducted from 2005 to 2009 and involving the use of radio-tagged fish has recently provided the first empirical data on adult salmon and steelhead behavior and movement patterns in the Toutle River since the 1980 eruption; this study found that (1) the SRS spillway served as a complete migration barrier for all coho salmon and all but 3 of the 23 released steelhead; (2) a large percentage of tagged steelhead released into the SRS sediment plain (69%) could move upstream to potential spawning areas, although success was much lower for coho salmon; (3) the FCF was not efficient at collecting adult salmon; and (4) none of the tagged fish released in the tributaries where trap-and-haul fish were commonly released left those tributaries (Liedtke et al., 2013). These results collectively underscore the challenge that the SRS and its associated sediment plain pose for fish passage into the upper North Fork Toutle River.

Currently, upstream volitional fish passage is blocked downstream of the SRS by the barrier dam at the FCF as well as by the head cut at the base of the spillway channel (USACE, 2017), while upstream migration from the North Fork Toutle River into Spirit Lake is completely blocked by the debris avalanche and the Spirit Lake tunnel. Downstream migration of outgoing smolts has been less frequently addressed, but it is still an issue for young fish hatched upstream of the SRS. For example, the hydraulic design goals associated with the 2012 SRS spillway raise included maintenance of

downstream fish passage and the promotion of a separated and vegetated floodplain terrace in the flat sediment plain above the spillway (Britton et al., 2016b). If restoring volitional fish passage in the North Fork Toutle River system is identified as a management objective for this project, then decision makers and managers will need to assess how different actions, either at the SRS or Spirit Lake, affect fish migration.

A number of issues and approaches for restoring or enhancing volitional fish passage at the SRS were discussed in the final revised DSEIS for the Mount St. Helens Long-Term Sediment Management Plan (USACE, 2017) (see Box 3.4). Two basic and relevant conclusions of that report and the NMFS biological opinion that informed it are that (1) future modifications of the SRS spillway would likely be required to facilitate fish passage through the spillway channel to allow individuals to move upstream into the sediment plain and (2) raising the SRS could potentially harm out-migrating juvenile Coho salmon and steelhead because the raise would result in increased sediment storage upstream of the SRS, which would also adversely modify the physical and biological features that contribute to the migratory pathway component of designated critical habitat. Those conclusions and the information used to support them, however, need to be further assessed and validated because the final revised DSEIS was not released in time to inform deliberations for the present report. Furthermore, any actions to restore volitional fish passage all the way to and from Spirit Lake (e.g., through creation of an overland channel) need to consider the full range of impediments to fish passage, including those imposed by the Fish Collection Facility, the SRS, the SRS sediment plain, and the feature used to provide outflow for Spirit Lake.

Apart from operating the Fish Collection Facility, the WDFW manages the Mount St. Helens Wildlife Area (MSHWA), established in 1990 to protect elk winter range on the North Fork Toutle River mudflow that resulted from the 1980 eruption.20 Most of the 2,744 acres (1,110 hectares) comprising the MSHWA were acquired through a land exchange with the Weyerhaeuser Company, with assistance from the Rocky Mountain Elk

___________________

20 See http://wdfw.wa.gov/lands/wildlife_areas/mount_saint_helens.

Foundation; in exchange, the WDFW traded two parcels in Cowlitz and Yakima Counties for 2,212 acres (Calkins, 2006). More recently, a 2009 land transfer from the Washington State Department of Transportation expanded the wildlife area to its current size. The MSHWA is bordered by Weyerhaeuser lands on the north, WADNR lands to the south, and the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument to the east (see Figure 3.1).

The initial management plan for the MSHWA was drafted in 1990 by a team of WDFW scientists, managers, and enforcement personnel because there were no new additional state funds allocated for management of the new wildlife area. (Note that development of the initial management plan is detailed in Calkins [2006], from which the following summary is drawn.) The 1990 Management Plan stressed two broad objectives: (1) “protecting and improving lands and water habitats to assure optimal number, diversity and distribution of wildlife for the welfare of the people of Washington state,” and (2) “providing the highest quality wintering elk habitat in the North Fork Toutle River drainage while allowing public viewing and limited recreation” (Calkins, 2006: 42). Extensive efforts have thus been made to improve elk winter forage, including erosion control, weed control, fertilization and vegetation plantings, and a winter feeding program, when necessary.21 Furthermore, while the focus of the MSHWA as outlined in the 1990 Management Plan was on the protection and management of elk that spend their winters in the Toutle River valley, the implementation of habitat management measures that contribute to the recovery of fish populations in the Toutle River basin was added as a central management objective for the MSHWA in the 2006 Mount St. Helens Wildlife Area Plan. In particular, recovery of fish species protected under the ESA is a key statewide and regional goal of the WDFW.

INTERESTED AND AFFECTED PARTIES

Management of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system as defined in this report will necessarily involve consideration of the safety of

___________________

21 See http://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/00480/mt_st_helens_2014update.pdf.

the downstream communities, the protection of the local and regional ecology and economic activities, and other considerations. Because the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system encompasses public and private lands, no single entity is responsible for management of the entire system. Furthermore, as described earlier in this report, public landowners have distinct and sometimes contradictory public service missions and mandates. Members of the public served by those agencies are affected directly or indirectly by the management of the system. They may also have specialized knowledge about the system that might be useful to inform decisions—for example, from their observations of the behavior of fish and other species affected by ecological changes. These people will likely have a wide array of priorities that need to be addressed in some way during the decision-making processes, both to facilitate acceptance and implementation of decisions and to arrive at decisions that take into account all relevant knowledge.

Interested and affected parties are the agencies, individuals, organizations, institutions, groups, and communities that may be making or are affected directly or indirectly by a given set of decisions. Decision makers are also considered interested and affected parties because they, too, have an interest in the results and are affected by the outcomes of their decision. Parties may be affected by various combinations of statutory, legal, and administrative choices, which may in turn raise economic, political, and sociocultural concerns. Moreover, different concerns may be salient for different groups. While the regulatory and management concerns and responsibilities of responsible agencies may be assumed a priori on the basis of their statutory foundations, understanding the range of concerns of other interested and affected parties that need to be considered during decision making requires empirical efforts. Such efforts may include studies to identify the parties’ concerns, sometimes called stakeholder analyses; participatory processes that allow the parties to express their concerns directly to responsible agencies; or combinations of these approaches. Consciously seeking to understand the diversity of interests affected by management decisions may allow decision makers to better account for stakeholder concerns and minimize post-decision conflicts.

The two agencies explicitly charged with managing those lands and features of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system most relevant for this decision-making process are the USFS and the USACE. Their roles are diverse and have been discussed throughout this chapter, but they stem directly from the agencies’ responsibilities for managing the Monument, the level of Spirit Lake, the functions of the current Spirit Lake outflow tunnel, the SRS, levees along the lower Cowlitz River, and other aspects of the system related to sediment and water management. With respect to the decision framework addressed in this report (see Chapters 6-8), interested and affected parties include additional public agencies and groups at a range of political scales (federal, tribal, state, and local) as well as stakeholders from the private sector; these are described in the following sections.

Federal Agencies

Federal agencies beyond the USFS and the USACE might be considered interested and affected parties with respect to the management of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system. The USGS, located within the U.S. Department of the Interior, is a research organization with no regulatory responsibility. Legislation passed by Congress in 1974, however, made the USGS the lead federal agency responsible for providing reliable and timely warnings of volcanic hazards to state and local authorities.22 Under this mandate and recognizing the need to continue surveillance of Mount St. Helens, the USGS created the David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory (CVO) in Vancouver, Washington—part of the larger USGS Volcano Hazards Program—to develop and maintain a network to track volcanic and seismic activity.23 Scientists from the CVO have studied many aspects of the Mount St. Helens system since the 1980 eruption, and they work closely with scientists from other agencies, including the USFS and the USACE, to provide technical advice and hazard warnings to local, state, and federal stakeholders.24

___________________

22 See https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/msh/scientists.html.

23 See https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/observatories/cvo/cvo_about.html.

24 See https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/observatories/cvo/cvo_about.html.

Certain management decisions regarding the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system would necessarily involve other federal agencies if they trigger actions under provisions of the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, or other federal environmental legislation. The act (ESA 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.)25 was signed in 1973 to protect and recover imperiled species and the ecosystems upon which they depend. It is administered by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), which has primary responsibility for terrestrial and freshwater organisms, and the Commerce Department’s National Marine Fisheries Service, which has primary responsibility for marine wildlife, including anadromous fish such as salmon and steelhead,26 both of which are historic components of the Toutle River system. Furthermore, the NEPA (NEPA, 42 U.S.C. 4321 § et seq.),27 signed in 1970, requires all federal agencies to conduct detailed evaluations (i.e., environmental assessments and environmental impact statements) of the environmental impact of and alternatives to major federal actions significantly affecting the environment.28 The NEPA process, which is overseen by the President’s Council on Environmental Quality and may involve organizations such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, mandates that agencies provide opportunities for public review and comment on those evaluations. Other relevant legislation could include (1) the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act and its amendment; (2) the Sustainable Fisheries Act of 1996, which establishes requirements for essential fish habitat for commercially important fish; and (3) the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1934, which requires federal agencies involved in water resource development to consult with the USFWS and state agencies administering wildlife resources concerning proposed actions or plans (USACE, 2012).

___________________

25 See https://www.fws.gov/endangered/esa-library/pdf/ESAall.pdf.

26 See https://www.fws.gov/endangered/laws-policies/index.html.

27 See https://ceq.doe.gov/laws_and_executive_orders/the_nepa_statute.html.

28 See https://www.epa.gov/nepa/what-national-environmental-policy-act.

Tribal Nations

Native Americans have lived in and influenced the ecology of the region for more than 6,000 years, hunting and later gathering food and other necessities from the area surrounding Mount St. Helens. The forest’s resources allowed larger, more settled populations, and people began to manage the landscape more actively (e.g., by burning) for game and other food.29 An estimated 6,000 members of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe lived in about 30 villages along the Cowlitz River and its tributaries at the time of their first contact with Europeans and Americans (Wilma, 2005). Native Americans living in the region were familiar with Mount St. Helens and the geological risk it posed, naming it “Lawetlat’la” (the Smoker) and “Loowit” (Keeper of the Fire) (Olson, 2016), and the mountain was important to the indigenous cultural identity of citizens of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe (McClure and Reynolds, 2015). This significance was recognized in 2013 when 12,501 acres (5,059 hectares) of the Monument were officially listed in the National Register of Historic Places for its significance as a Traditional Cultural Property.30 The Cowlitz Indian Tribe provides services related to housing, health, and transportation to about 4,100 tribal members, many of whom live in southwest Washington, including in areas protected by lower Cowlitz River levees (USACE, 2017).

The landscape surrounding Mount St. Helens was nominated for designation as a Traditional Cultural Property by the USFS and the Cowlitz Indian Tribe because of its significance as a cultural landscape central to the oral traditions, geography, and identity of its native peoples. At the time, Cowlitz Tribal Council Chairman William Iyall said:

___________________

29 See http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/giffordpinchot/learning/history-culture/?cid=STELPRDB5172182.

30 This designation stems from National Register Bulletin 38 (Parker and King, 1990), which presented guidelines for evaluating the eligibility of sites for inclusion in the National Register based on their cultural significance. Criteria were related to the historical and ongoing relationships between the property and the cultural practices, values, and beliefs of the people for whom the property has importance (Smythe, 2009). Perhaps the greatest benefit of Bulletin 38, nationally, has been its role in raising public and agency awareness about the traditional cultural significance of places of importance to Native American Tribes, including landscape features imbued with sacred qualities and tied to tribal histories (Lusignan, 2009; McClure and Reynolds, 2015).

The listing of Lawetlat’la as a Traditional Cultural Property honors the long relationship between the Cowlitz People and one of the principal features of our traditional landscape. For millennia, the mountain has been a place where Tribal members went to seek spiritual guidance. She has erupted many times in our memory, but each time has rebuilt herself anew. She demonstrates that a slow and patient path of restoration is the successful one. (U.S. Forest Service, 2013: 1)

During the committee’s open session meetings in Kelso, representatives of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe described distinct aspects of tribal culture likely to influence their positions on long-term management of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River region. One set of beliefs centers on the need to adjust to rather than control natural processes such as volcanic activity and periodic eruptions—inevitable given this particular geologic and geographic setting. Given this familiarity with and respect for the active volcanic history of Mount St. Helens, ancestors of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe developed what Euro-Americans might call a management strategy for “living with the volcano” (see Box 3.7). Related to this tradition is the tribe’s views on time horizons, which could affect tribal positions on the definition of “long-term management.” The tribe desires protection, conservation, restoration, and promotion of culturally relevant species, including anadromous fish, deer, elk, mountain goats and other species,31and landscapes integral to their unique identity. Spokesmen for the tribe have also expressed special concerns about the impacts of the SRS on the environmental conditions of the North Fork Toutle River, particularly with respect to salmon and steelhead populations.

In addition to the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, the Yakama Nation has been interested in the preservation and management of their traditional use lands in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. The Yakama reservation is located adjacent to the eastern boundary of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, and the Yakama people continue to engage in ceremonial, subsistence, and commercial fishing for salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon in the Columbia River and its tributaries.32

___________________

31 See http://cowlitz.org/index.php/natural-resources-mission-statement.

While there is a tendency to focus on the social, cultural, and historical contributions of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and the Yakama Nation when considering management of the region, members of these groups possess an array of relevant expert knowledge, skills, and capabilities regarding the physical, biological, and environmental aspects of the study system that are relevant to the decision-making framework. As is noted in the USACE’s Mount St. Helens Long-term Sediment Management Plan (2017), the Cowlitz Indian Tribe has been particularly active in the North Fork Toutle River watershed, which lies in the heart of the tribe’s ancestral lands, where they have conducted fish and habitat research, restored and protected critical salmonid habitat, and assisted in trap and haul efforts at the FCF and worked closely with the WDFW and other stakeholders to protect and conserve resources of the Toutle River. In terms of technical expertise, the Cowlitz and Yakama communities both have highly trained scientists and technicians that perform and publish the results of fundamental scientific research as well as established programs in wildlife,

fisheries, range, and vegetation resources management that are engaged in restoration and conservation projects in rivers draining to the Columbia River. These programs receive funding from the Bonneville Power Administration through the Fish Accords.33

State Agencies

The role of the WDFW in managing the MSHWA and the FCF has already been described. Given its dual mission of protecting, restoring, and enhancing fish and wildlife and their habitats while also providing sustainable fish and wildlife-related recreational and commercial opportunities, the WDFW has a valid interest in any actions with respect to the management of Spirit Lake and the Toutle River that affect those resources. At the MSHWA, that would especially include a focus on anadromous and resident fish populations as well as elk and their winter habitat along the North Fork Toutle River.

In addition to the WDFW, the WADNR has a stake in the Spirit Lake decision. Created by the state legislature in 1957, WADNR now manages 5.6 million acres (2.3 million hectares) of forest, range, agricultural, aquatic, and commercial lands throughout the state for more than $200 million in annual financial benefit for public schools, state institutions, and county services.34 In the Toutle River watershed, it manages 37,100 acres (15,014 hectares) of state-owned trust lands immediately west of the Monument between the North Fork and South Fork Toutle Rivers as well as smaller parcels elsewhere in the watershed (see Figure 3.1).

The Washington State Department of Ecology is Washington’s environmental protection agency and has a mission “to protect, preserve and enhance the State’s land, air, and water for current and future generations.”35 The department is also primarily responsible for the regulation of dams on state and private lands. In the case of work at Mount St. Helens,

___________________

33 See, for example, http://www.yakamafish-nsn.gov and https://www.cowlitz.org/index.php/contacts/15-natural-resources; https://www.ynwildlife.org/aboutus.php.

34 See http://www.dnr.wa.gov/about-washington-department-natural-resources.

the Department of Ecology (in conjunction with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) would be involved if construction debris from dam-related projects needs to be disposed off-site. Other state agencies that also may be affected by management of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system include (1) the Washington State Governor’s Office for Regulatory Innovation and Assistance (ORIA), which serves as first point of contact for project planners to help determine which Washington State regulations are pertinent and which state agencies potentially need to be involved; (2) the Washington State Department of Transportation, which would have an interest in understanding the risks associated with management of sediment and water transport in the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers; (3) the Washington Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, which advocates for the preservation of irreplaceable historic and cultural resources, including significant buildings, structures, sites, objects, and districts36; and (4) and the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, which manages Seaquest State Park and the Mount St. Helens Visitor Center, both of which are near Silver Lake within the Toutle River watershed.

County and Other Local Governments

The Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument is an important natural resource and tourist attraction for Cowlitz, Skamania, and Lewis Counties. The communities that would be most directly affected by a catastrophic failure of the Spirit Lake debris blockage are located primarily in Cowlitz County. These are also gateway tourism communities for the west side of the Cascades. The Cowlitz River valley is a major interstate and freight corridor between Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington. Numerous county and local government agencies have responsibilities related to economic development, public safety, and emergency management, including management related to chronic and catastrophic floods. Specific issues of importance to such entities could include life safety, damage to private lands, public facilities and water systems, and critical areas as

___________________

36 See http://www.dahp.wa.gov.

defined under the Washington State Growth Management Act (RCW 36.70A.02037) (cf. Granger et al., 2005). Sediment accumulation in the Cowlitz River poses problems for river navigation, particularly shipping associated with the Port of Longview at the confluence of the Cowlitz and Columbia Rivers.

Nongovernmental Organizations, Businesses, and Local Residents

Individuals, businesses, and communities in the region are all potentially affected by Spirit Lake and Toutle River management decisions, so their interests and concerns need to be considered. Many active nongovernmental organizations interested in the region seek to represent these interests and concerns and to speak for subsets of the interested and affected parties. The goals, interests, and objectives of such parties are diverse, however. These include groups focused on environmental education (e.g., the Mount St. Helens Institute), recreation (e.g., the Cowlitz Game and Anglers), economic development and tourism (Toutle Valley Community Association), and conservation (e.g., Gifford Pinchot Task Force), to name just a few. Such groups, many of which were involved in the open session committee meetings in Kelso associated with this report, can help to coalesce the concerns of some of these interested and affected parties, though it should not be assumed that all relevant concerns will be represented by existing organized groups. They can also bring into the process decision-relevant observations of conditions and changes in the system that may not yet have been made by public officials.

A COMMON UNDERSTANDING FOR SYSTEM MANAGEMENT

A complex relationship has developed between the USFS and the USACE around the management of Spirit Lake given the different missions and functions of the agencies. Perceptions regarding the problems requiring

___________________

37 See http://apps.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=36.70A.020.

action, management objectives, and management alternatives are influenced by these different missions. Likewise, their respective views will be different when considering the consequences—good and bad—of decisions. Funding and the political climate at any given time further complicates their relationship and the decisions they can make. Management of system elements downstream—for example, in the North Fork Toutle River near the SRS—is even more complex because many federal, tribal, state, local, and private entities have their own responsibilities and interests related to different aspects of the valley. The narrative thus far reflects ad hoc management of each element by the different agencies with modest consideration of how the elements interact.

As described in Chapter 1, the USFS has expressed interest in applying a systems approach to managing water levels in Spirit Lake and in the transport of water and sediment in the Toutle River system. Chapter 2 described how doing so is important and how decision making needs to consider both physical attributes of the system, and also socioeconomic conditions of the interested and affected parties. A holistic conceptualization of the system can be accomplished only if interested and affected parties beyond those with immediate management authority are engaged in meaningful ways. This means engaging the parties in developing shared definitions of the system and shared understandings of the nature of the problem, goals, potential solutions, and feasibility of those solutions. The parties need a shared vocabulary.

Recommendation: Responsible agencies and other interested and affected parties should develop a common understanding of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system, its features, hazards, and management alternatives.

Improved communication comes from common understanding of region-wide issues and will result in more productive identification of problems and management alternatives. Transparency and regular interaction and information sharing makes developing that common understanding more likely. Differences among interested and affected parties might be

transcended through a deliberative and participatory process. This is discussed in Chapter 6.

No single organization understands all aspects of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system: the USFS does not have the engineering expertise needed for managing Spirit Lake, but the USFS and the USGS conduct joint research in and around Spirit Lake and have developed understanding of environmental and geologic processes. Flood risk management engineers may not appreciate the extraordinary magnitude of lahars and lake breakout floods (see Chapter 4); and geologists, with field evidence of the history of such catastrophes, may have little expertise in practical flood hazard management.

Engaging Interested and Affected Parties

The literature is replete with examples of how interested and affected parties might be involved in decision making, ranging from highly structured elicitation methods to less-structured and informal approaches. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration guidance on interested and affected party participation in coastal decision making (2015), for example, identifies more than a dozen ways to obtain input, including workshops, town meetings, public hearings, surveys, focus groups, and the formation of advisory committees. Similarly, Aven and Renn (2010) highlight interested public hearings, roundtables, negotiated rule making, mediation, surveys, and focus groups as mechanisms for gathering information from interested and affected parties. More formal approaches such as that recommended in Chapter 6 of this report specify how interested and affected party values, objectives, and judgments regarding outcomes can be systematically incorporated into decision processes. The National Research Council’s report titled Public Participation in Environmental Assessment and Decision Making (NRC, 2008) identified principles for effective management of these processes, process design, and integrating science with participation. For example, the process design principles are: “(1) inclusiveness of participation, (2) collaborative problem formulation and process design, (3) transparency of the process, and (4) good-faith communication” (NRC, 2008: 230). The

best approach to implement these principles, the report notes, is dependent on context.

Identifying Interested and Affected Parties

The study committee did not conduct a scientific survey of interested and affected parties in the region, nor was an effort made to ensure that those participating in public meetings represented a scientific sampling of the points of view held in the region. The interested and affected parties contacted during the course of this project are summarized in Table 1.1. The committee’s open session meetings attracted a diverse group of attendees, including congressional member office staff, scientists and consultants, community leaders, science writers, reporters, and others, and discussions yielded diverse and complicated interests among these parties. Several themes emerged during the discussions, some of which are highlighted below. A common understanding of these and other such themes that come about during future discussions will aid more productive communication and deliberation.

The wide range of interested and affected parties and their respective concerns described in this chapter illustrate how difficult it will be to develop a common understanding of the Spirit Lake and Toutle River system, of the physical and socioeconomic consequences of management alternatives, and of how to reach decisions that will address the diverse concerns. The material offered herein could be considered a starting point for future deliberation among decision makers and other interested and affected parties. A common understanding of issues for the region will improve communication, lead to better identification of problems and alternatives to solve those problems, and might help build trust among agencies and other interested and affected parties by removing unintentional misunderstandings.

Broadening the Range of Potential Benefits to Management

Many decisions made in the wake of the 1980 eruption were reached under emergency conditions, with limited information and when the effects of the

eruption were fresh in residents’ minds. The future decision process might be more deliberative and better informed with new information, data, and perspectives. In this context, all the participants heard from during open session meetings recognized that any decisions need to incorporate the current and future safety of citizens downstream of the Spirit Lake blockage. There was also support for evaluating a broader range of goals and benefits such as improving recreational opportunities; improving fish habitat and passage; improving habitat for elk and other fauna and flora of the region; reducing the likelihood of both chronic and catastrophic flooding; containing costs associated with long-term management; sustaining emergency response capabilities; helping allay the concerns for residents concerned about floods and other hazards; managing sediment flows through a variety of means; recognizing and honoring distinctive Native American Indian values and cultural practices; having the ability to make repairs to structures such as the Spirit Lake tunnel without increasing flood risk; minimizing the risks to personnel involved in maintaining management infrastructure (e.g., the Spirit Lake tunnel); and maintaining decision-making flexibility in the face of environmental uncertainties going forward.

GREATER “NATURALNESS” AND DECREASED RELIANCE ON ENGINEERED SOLUTIONS

A lack of common understanding regarding the consequences for various management alternatives is apparent among all interested and affected parties, even among those representing federal agencies. Following the eruption, public agencies (especially the USACE) were called to address threats to downstream human safety and economic concerns. A number of participants in the committee’s open session meetings echoed variations of sentiments similar to that provided by George Fornes, Habitat Conservation, Protection & Restoration program biologist for the WDFW. He noted that the “WDFW continues to support an approach involving decreased reliance on engineered solutions. We encourage those involved to work toward restoring natural processes” (George Fornes to Sammantha Magsino, August 11, 2016). The desire for a more natural system was

based on several objectives, including (a) economic recovery—for example, a desire for a return of tourism in the Toutle River valley centered on outdoor activities such as sport fishing for salmon, steelhead, and trout; (b) ecological restoration, including the recovery of native nongame species, but especially focused on anadromous fish species; and (c) the promotion of intrinsic and aesthetic values, including the historic and cultural significance of the valley for the Cowlitz Indian Tribe. It was not clear, however, that interested and affected parties necessarily agreed on what was meant by “natural,” on what a more “natural” valley would be, or on what would be the potential consequences of decisions regarding engineered structures such as the Spirit Lake tunnel or the SRS. Nor was it clear that interested and affected parties understand that the 1980 volcanic eruption (a natural and recurring process) changed the system to create a different natural setting and a “new normal” for the foreseeable future. No measures taken could revert the system back to pre-1980 conditions. The lack of common understanding is a problem explored in other environmental and water sensitive areas, such as the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (USACE and SFWMD, 1999) and the National Academies report on sustainable water and environmental management of the California Bay-Delta (NRC, 2012a). Chapters 6-8 provide suggestions regarding how to develop a common understanding among decision makers.

GREATER TRANSPARENCY AND INVOLVEMENT IN THE DECISION PROCESS

The NEPA requires that decisions concerning actions to be taken by federal agencies such as the USFS or the USACE that may significantly affect the environment must include opportunities for public comment, and public comments have been elicited in the past. Nevertheless, during the committee’s open session meetings private citizens and representatives from a number of interested and affected groups expressed frustration that the participatory processes for previous decisions regarding Toutle River management had been insufficient and non-transparent. Some participants expressed a lack of trust in the decision-making process or the agencies

involved. A desire was expressed that public engagement involving the Spirit Lake outflow should not only meet the legal requirements for public input but also seek meaningful engagement with interested and affected parties and build trust where trust is lacking.

MANAGEMENT COMPLICATED BY INSTITUTIONAL SITUATION

As has been described throughout this chapter, the management of Spirit Lake is complex for a number of reasons. First, the jurisdiction and management responsibilities for the lands and related features within the Monument, including Spirit Lake and the tunnel outflow, lie with the USFS, but the USACE performs all operation and maintenance activities on the Spirit Lake tunnel itself, including monitoring and inspection. The SRS is operated by the USACE so upstream decisions that affect sediment flow into the SRS affect the life span of the structure and have implications for downstream flood and sediment management. Similarly, management of the SRS affects fish migration, for example, which necessitates involvement of such organizations as the National Marine Fisheries Service under the auspices of the ESA. The USACE is also authorized by Congress to maintain authorized flood damage reduction benefits for the Longview, Kelso, Lexington, and Castle Rock levees through the end of the Mount St. Helens project planning period in 2035. Various relationships have been authorized between federal and state agencies to accommodate these responsibilities. No mechanisms exist to manage these as a system.