3

The National Landscape of Health Care Training and Workforce Processes

The workforce involved in promoting children’s cognitive, affective, and behavioral health is broad and varied. It includes pediatricians, adult and child psychiatrists, family medicine physicians, obstetricians and gynecologists, nurses, community and public health professionals, social workers, teachers and other school staff, and parents who have been trained to fill professional roles. Physicians may work in the fields of pediatrics, family medicine, psychiatry, obstetrics and gynecology, or a combined field. Pedi-

atric psychologists may work in primary care or subspecialty care. Nurses include registered nurses, nurse practitioners (including pediatric, family, and psychiatric nurse practitioners), and primary care mental health nurses. Social workers with bachelor’s or master’s degrees may work in the fields of behavioral health, substance use and addiction, or youth and families. Parent and peer support providers, parent coaches, and community health workers may all work on behalf of children’s behavioral health.

As Thomas Boat, dean emeritus of the College of Medicine at the University of Cincinnati, professor of pediatrics in the Division of Pulmonary Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and cochair of the workshop planning committee, pointed out during a panel discussion of health care training and workforce processes, all of these groups are the products of workforce training and, to some extent, all are involved in that training. As a specific example, Boat observed that “some residents are now training both in pediatrics or family medicine and in psychiatry or child and adolescent psychiatry. If we had more of those people, they would be a major asset to what we’re trying to do.”

Boat was the lead author of a discussion paper released the day of the workshop titled “Workforce Development to Enhance the Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health of Children and Youth: Opportunities and Barriers in Child Health Care Training.”1 The paper points to shortfalls in all disciplines in the numbers of individuals who are positioned to promote children’s cognitive, affective, and behavioral health. The number of physicians, for example, who are trained to address the behavioral health needs of children and families “falls woefully short of what we should have in place,” said Boat. Model programs and pathways exist for training of the workforce (as described in the next chapter), but none of them has been disseminated or systematically vetted in health care settings, “and they need to be,” Boat observed. Nor is competence in this area a stated expectation of licensing, certification, or program accreditation bodies, which is an opportunity that should be exploited, Boat said.

The discussion paper lays out training pathways for eight different disciplines. For pediatrics, for example, it describes 3-year programs for both core pediatrics and subspecialty pediatrics. It then cites curriculum guidelines and defined competencies for cognitive, affective, and behavioral health. It also provides the numbers of training programs and a general sense of workforce numbers. “Hopefully these data are helpful in terms of being able to focus our attention and our efforts going forward,” Boat said.

The paper describes models of highly integrated care in an effort to

___________________

1 The paper is available at https://nam.edu/workforce-development-to-enhance-the-cognitive-affective-and-behavioral-health-of-children-and-youth-opportunities-and-barriers-in-child-health-care-training [September 2017].

understand what works and how successful models can be transported to other health care areas. It also discusses the need to train the workforce of the future to conduct program evaluation and outcomes research, which Boat called “an important consideration as we go forward.” In addition, more cross-disciplinary training will be an important future objective. Overall, the paper is a platform for thinking about what is being done now and what can be done in the future, said Boat. “As we go through this workshop, hopefully we can extend these considerations. . . . I hope that this paper will catalyze your thinking about what you can do individually and at your programs at home to further the cause of promoting children’s cognitive, affective, and behavioral health.”

After Boat’s introduction of the background paper, panelists looked at different sectors to provide an overview of the current and projected workforce and the status of training across multiple disciplines that serve children and families.

THE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH WORKFORCE: SUPPLY, DEMAND, CHALLENGES, AND OPPORTUNITIES

The field of behavioral health, which encompasses people who are involved in the prevention or treatment of behavioral health and substance use disorders, is in the midst of a workforce crisis, observed Angela Beck, director of the Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. According to a report by the Annapolis Coalition on the Behavioral Health Workforce (2007), the crisis has several interconnected elements:

- an increased demand for behavioral health services,

- too few workers to meet the demand,

- a poorly distributed workforce,

- a need for additional training,

- an increased emphasis on integrated team-based care and treatment of co-occurring disorders, and

- a lack of systematic workforce data collection in behavioral health.

The core licensed professionals in the behavioral health workforce are psychiatrists, psychologists, marriage and family therapists, social workers, licensed professional counselors, and psychiatric nurse practitioners, Beck explained. Certified professionals include addiction counselors, peer providers, psychiatric rehabilitation specialists, psychiatric aides/technicians, and case managers. Not all people working in behavioral health are licensed or certified, said Beck, “but there are opportunities for licensure and certification for many behavioral health occupations.” Primary care providers

also serve as frontline behavioral health providers, regardless of whether they have specialized training in this area. She noted that behavioral health workforce capacity covers a very diverse set of occupations.

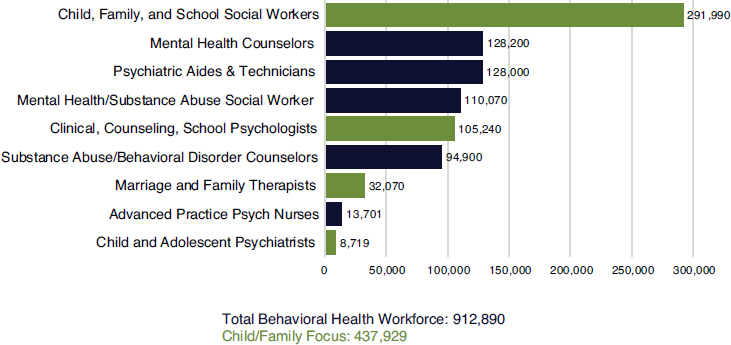

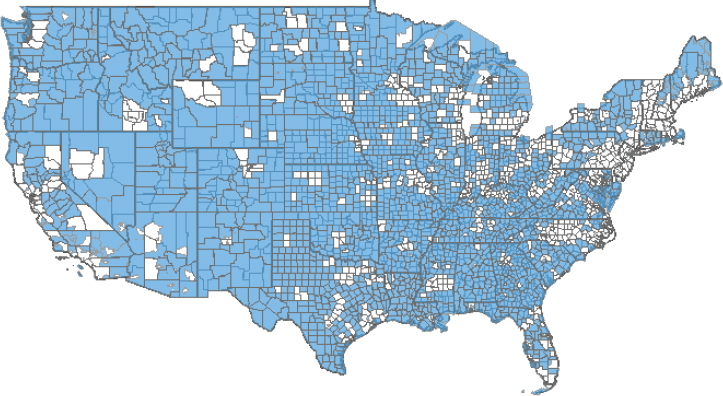

More than 900,000 core licensed professionals work in behavioral health (see Figure 3-1), though the numbers vary depending on the data source. This workforce is maldistributed across the United States, she added (see Figure 3-2). About 4,000 behavioral health Health Profession Shortage Areas (HPSAs), as designated by the Health Resources and Services Administration, currently exist, with an increase of about 300 HPSAs since 2012. Approximately 2,800 psychiatrists are needed to address the shortage, said Beck. More than one-half (55%) of U.S. counties, mostly in rural areas, have no practicing psychiatrists or social workers.

Calculating how many more behavioral health workers are needed is a difficult problem. It depends on the extent of unmet needs, the distribution of future workers, and other factors. It also is an important question, Beck said, “because we know that mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders in youth are costly in the health care system [and] that youth behavioral health concerns have reportedly increased over time.”

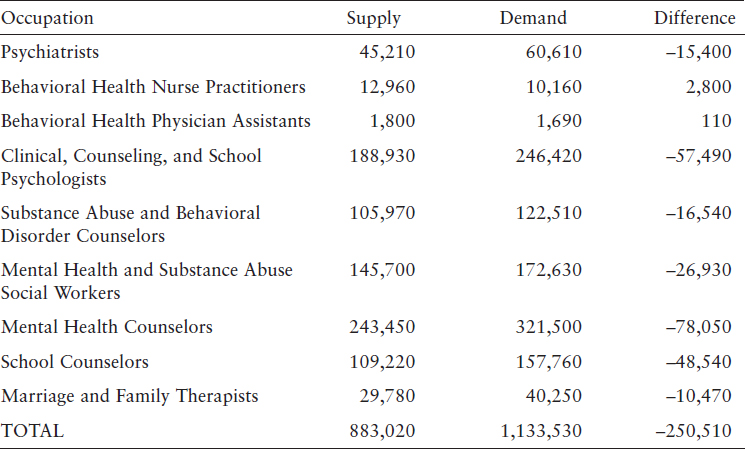

According to recent projections from the Health Resources and Services Administration (2016), shortages will continue to be substantial among core licensed professionals in 2025, with the exception of behavioral health nurse practitioners and physician assistants (see Table 3-1). The total shortage in the selected behavioral health occupations is projected to be about 250,000 workers. This list does not include peer providers or other nonli-

SOURCE: Beck (2016).

SOURCE: Beck (2016).

censed workers, and it is not specific to children and families, but she said she did not think the numbers would improve by including these types of workers.

Beck concluded by listing some of the challenges and opportunities for behavioral health workforce development. The recruitment and retention of workers is a challenge, particularly given the high turnover in the field. The workforce is aging, more workers are needed in rural areas, the workforce needs to become more diverse, and people serving specialized populations need more specialized training, she observed. She also pointed out that scopes of practice both enhance and limit the capabilities of the workforce. “Recommendations or priorities around scopes of practice may be important to keep in mind,” she suggested.

NURSES AND SCHOOLS AS PROVIDERS OF BEHAVIORAL HEALTH SERVICES

Susan Chapman, professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing, spoke about two valuable providers of behavioral health services in communities: nurses and schools.

SOURCE: Beck (2016).

Nurses, with a Focus on Psychiatric Nurse Practitioners

Nurses, including pediatric nurse practitioners, family nurse practitioners, and psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners, are particularly valuable providers of child and family behavioral health services, noted Chapman. According to a 2016 survey, 14 percent of psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners reported working predominantly with people ages 1–20 (Delaney et al., 2016), while 19 percent provided no services to children and adolescents. In a national survey of registered nurses, only 4 percent report working in behavioral health or substance abuse and 6 percent in pediatric specialties (Budden et al., 2013).

The supply of psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners is between 9,000 and 19,000, said Chapman, depending on the source of the data. Certification began as that of a clinical nurse specialist but now is primarily a nurse practitioner, with the scope of practice varying by state. It is a growing profession, with 118 nursing programs training psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners.

Psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners provide many of the same services that psychiatrists provide, including the ability to prescribe medications, Chapman observed. They are educated in an integrative practice model that stresses physical and behavioral health and emphasizes health

promotion. Research shows that patient satisfaction with their care has been high. They also have a shorter training time than for psychiatry. However, scope of practice limitations, which vary by state, have regulatory requirements for physician supervision in some states. Also, she said, recruiting and retaining psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners is sometimes difficult, a lack of awareness surrounds their roles and competencies, their salaries are generally not competitive in public settings, and they still can have difficulties being accepted by other providers on health care teams.

Schools

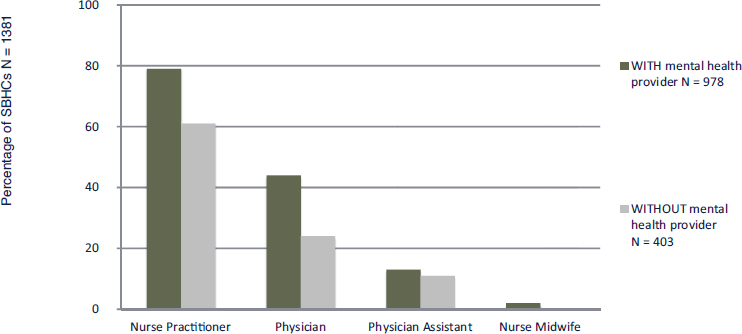

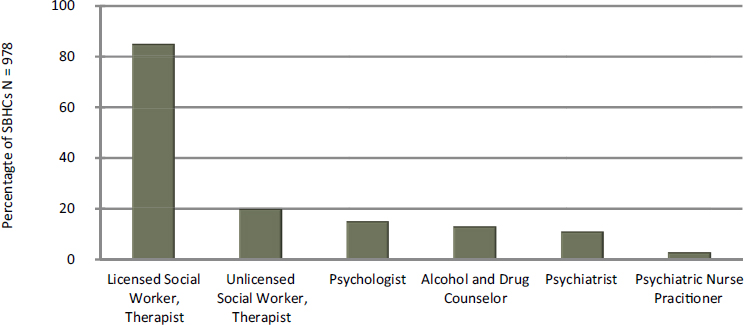

Schools present another valuable opportunity for enhancing behavioral health services, noted Chapman, citing research that 70 percent of U.S. public schools offer behavioral health services, but only 2 percent have school-based health centers (Larson, 2016). Most of these are staffed by nurse practitioners (see Figure 3-3), with physicians, physician assistants, and nurse midwifes playing smaller roles. Among the behavioral health care providers in school-based health centers, licensed social workers and therapists play the largest role (see Figure 3-4). Only 3 percent had psychiatric nurse practitioners, Chapman noted.

In an analysis of survey data from California of more than 600,000 students, high percentages of students, generally between about 20 and 50 percent at various grade levels, had experienced sexual gestures and jokes, rumors and lies, being made fun of, being pushed or kicked, and having property stolen or damaged (Larson et al., 2017). In addition, about one-

SOURCE: Chapman (2016). Data from Larson et al. (2017).

SOURCE: Chapman (2016). Data from Larson et al. (2017).

quarter of 11th and 12th graders have consumed five or more drinks in a row in the last month. “Clearly the need is here,” she said.

Enhancing behavioral health services for children and families requires using every type of worker to the full capacity of his or her education and experience, Chapman said. Training also needs to be focused more on children and families and more on a team model, she said. Important questions are who needs to be on a team, how the team should integrate with primary care, and how the team can be inclusive of family, school, and community.

PEER PROVIDERS

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has defined a peer provider as “a person who uses his or her lived experience of recovery from mental illness and/or addiction, plus skills learned in formal training, to deliver services in behavioral health settings to promote mind-body recovery and resilience” (Kaplan, 2008). According to a study done at University of California, San Francisco, peer providers work in a variety of settings, including peer-run organizations, traditional care settings, and forensic care settings such as drug courts (Chapman et al., 2015). Medicaid reimbursement in recent years has enhanced such careers as an employment opportunity. However, training and certification “is a very mixed bag,” said Chapman. Forty states have statewide certification for behavioral health peer support, and about one-third have statewide certification for substance use disorders. In some places, peer providers continue to face stigma in being accepted and working alongside the professional workforce.

“Some organizations absolutely embrace this, and some are still hesitant,” she commented, noting that evidence of efficacy for peer providers is still somewhat mixed.

Elaborating on the concept, Johanna Bergan, executive director of Youth Motivating Others through Voices of Experience (M.O.V.E.), explained peer support is based on the establishment of a mutual connection between two people who have had similar experiences. M.O.V.E. promotes the use of peers to infuse the youth voice in systems transformation. “As we in this room are thinking about important policies that we may want to implement in the future, it is important, and in fact vital, that we include youth and young adult voices, as they will ultimately be the most affected by policy change,” Bergan stated.

Youth peer support is designed to meet the developmental needs of youth and young adults. Young people say many of the services they receive are not as appealing, attractive, and engaging as they should be and are not meeting their needs, Bergan explained. Young people are concerned about stigma, they often lack understanding of what is being offered to them, and they generally underuse the services that are available. M.O.V.E. has a national policy initiative called “What Helps, What Harms” and has compiled a list of priorities of its chapter members. A cross-cutting theme in the list is that education, awareness, and messaging need to come from peers, Bergan said.

Youth peer providers have many labels, including navigators, mentors, or helpers. They can provide assistance in navigating systems, support youth participation in treatment and service meetings, model positive self-advocacy and leadership, and provide guided support in individual recovery and in building resiliency. A limited amount of research points toward the value of peer support—especially youth peer support, and especially with groups such as first-generation college students and students with disabilities, said Bergan—but additional research on this topic is needed. Funding and other forms of support for that role can vary depending on the leadership within a state or with policy changes.

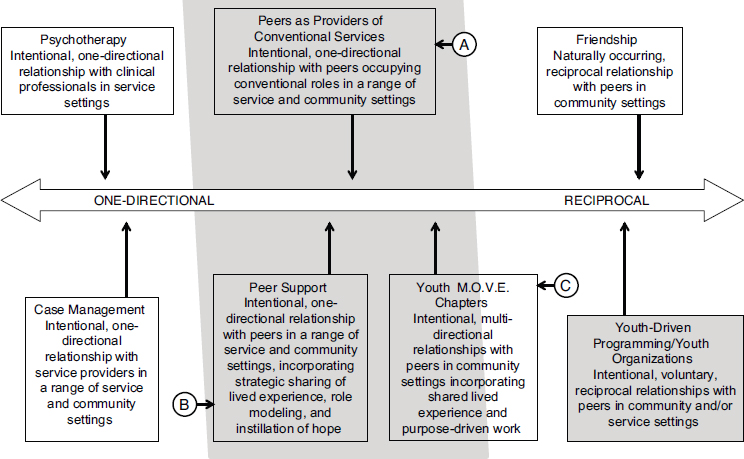

Peer providers can offer a continuum of helping relationships (see Figure 3-5). These relationships can be largely unidirectional, as with psychotherapy or case management. Alternately, they can be reciprocal, based on friendship and mutuality. “Peer roles can play across this continuum,” said Bergan. Some states are developing formalized roles for youth peers that involve training and certification. Informal peer roles may provide training to young people who are in school to notice things that are worrisome about their friends and be willing to reach out. Between these extremes, independent youth-driven organizations can complement the family movement and offer a particular culture and environment to young people and families who are looking for assistance.

SOURCE: Bergen (2016). Adapted from Davidson and Rowe (2006).

Bergan advocated for developmentally appropriate training that is appealing for youth transitioning into adulthood. Many young people interested in this subject want to become professionals, but other pathways can lead to service careers as well. Defining the peer role and identifying pathways for peers to move into other roles would help clarify the dimensions of the role. In addition, continuing education, both for youth peers who are already practicing and for those who interact with youth peers, can help reveal the value of their work, especially in team-based care. In addition, Bergan pointed out, each new level of required training, testing, and certification can act as a barrier to a young person with strong empathy skills who wants to offer support to his or her peers. “I want us to be intentional, when we put another certification requirement on the table, that there is either the flexibility to allow young people to approach and hop over that barrier in multiple ways or that we ask ourselves whether it is necessary to put that barrier in place,” she said. Bergan also pointed to the need to build a behavioral health work environment where lived experience is valued, so that the voices and opinions of young people are valued.

M.O.V.E. is developing a self-assessment tool that helps organizations understand and measure whether they are youth driven. The assessment includes nine components:

- Overall vision and commitment

- Collaborative approach

- Empowered representatives

- Commitment to facilitation and support of youth and young adult participation

- Organizational self-reflection and assessment

- Workforce development

- Participation in developing programming and program policies

- Participation in evaluation

- Leading initiatives and projects

As Bergan pointed out, peer providers generally are individuals who have disclosed their involvement with a particular system, whether behavioral health, juvenile justice, or child welfare. “Many of us are in this field because it is not only our passion but it is also our experience,” she said. “It’s with that lived experience component that we have a true peer definition.”

A MEDICAL STUDENT’S PERSPECTIVE

“Everybody remembers the first and second year of med school, where you sat in the library or in a corner and you studied and cried yourself to sleep and ate ramen noodles and studied again,” said Christen Johnson, a fourth-year medical student at Wright State University’s Boonshoft School of Medicine and national president of the Student National Medical Association. “That hasn’t really changed much. We may not use books per se; we use computers, but that’s about the only difference.”

The mission of the Student National Medical Association, which has more than 160 chapters, is to increase diversity in medicine, bring medical care to underserved communities, and change the culture of medicine. If students do not learn about social justice, advocacy, or health disparities when they are in medical school, they are unlikely to learn it later, said Johnson, adding, “I wanted to make sure other students understood how important that is.”

Every month the association has a different community service protocol in which students are charged with taking action in a particular area. Behavioral health was both a recent monthly service protocol and the 2015–2016 national focus. For example, one theme was reducing stigma surrounding behavioral health services, especially in underserved communities. Students talked with people in the community about why their behavioral health is as important as their physical health.

Johnson also observed that students are not spending enough time in medical school learning about many subjects they need to understand. For

example, they learn about behavioral health problems without understanding what actually happens in clinics. When Johnson had her psychiatry rotation, she related, “Honestly, I was terrified, because I was set in a room and there were toys being thrown and people were screaming at each other, and I had no idea what was going on and nobody had prepared me for this.” Medical school does not do a good job of preparing students for these kinds of experiences, she said. “The kid who was throwing the toy across the room maybe wasn’t trying to hit me with it; I just happened to be in the line of fire. But when you come from a place where you haven’t been taught this or explained this, it makes it much more difficult for students to understand,” she observed.

Another gap in the education of students involves continuity of care, Johnson pointed out. Students might learn about child psychiatry and adult psychiatry, but they do not necessarily learn about how the two are connected. They do not learn about children who have lived with pain their entire lives who transition into adulthood and need pain medications. “As physicians and as educators, we’re not doing the system justice by creating situations where medical students are hardened by the biases and the ideas of yesterday,” she said. “You have to give us the tools in our toolbox to be able to do what it is we need to do, and we are a lot less apprehensive. You’ll find a lot more students who will be willing to go not only into psychiatry but specifically work with children.”

DISCUSSION

A topic that arose during the discussion session involved community health workers, who are another source of workers in new models of care. One question, observed Chapman, is the role of lived experience and “whether that’s part of the community health worker background or not.” Certification, training, and payment are other issues, “but we’re certainly looking at community health workers as part of the [health care] team,” Chapman said.

Parents also can act as coaches for other parents, Boat pointed out, though they may have a somewhat different role description and training. Better understanding is needed of what parents can contribute, he said, “but we ought to welcome all of them into the family of health professionals.”